Abstract

Background and aims

The recent opioid epidemic has prompted renewed interest in opioid use disorder treatment, but there is little evidence regarding health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) outcomes in treatment programs. Measuring HRQoL represents an opportunity to consider outcomes of opioid use disorder treatment that are more patient-centered and more relevant to overall health than abstinence alone. We conducted a systematic literature review to explore the extent to which the collection of HRQoL by opioid treatment programs is documented in the treatment program literature.

Materials and methods

We searched PubMed, Embase PsycINFO and Web of Science for papers published between 1965 and 2015 that reported HRQoL outcome measures from substance abuse treatment programs.

Results

Of the 3014 unduplicated articles initially identified for screening, 99 articles met criteria for further review. Of those articles, 7 were unavailable in English; therefore 92 articles were reviewed. Of these articles, 44 included any quality-of-life measure, 17 of which included validated HRQoL measures, and 10 supported derivation of quality-adjusted life year utility weights. The most frequently used validated measure was the Addiction Severity Index (ASI). Non-U.S. and more recent studies were more likely to include a measure of HRQoL.

Conclusions

HRQoL measures are rarely used as outcomes in opioid treatment programs. The field should incorporate HRQoL measures as standard practice, especially measures that can be used to derive utility weights, such as the SF-12 or EQ-5D. These instruments provide policy makers with evidence on the impact of programs on patients’ lives and with data to quantify the value of investing in opioid use disorder treatments.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder treatment, Health-related quality-of-life, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Opioid misuse and opioid use disorders are pervasive public health problems globally. Worldwide, an estimated 28.6–38.0 million people used heroin or prescription opioids in the past year (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015) and approximately 69,000 died from opioid-related overdose in 2012 (World Health Organization, 2014). In the US, the rate of opioid overdose death in the US increased 200% from 2000 to 2014 and opioids killed an estimated 47,000 people in 2014 (Rudd, Aleshire, Zibbell, & Gladden, 2016). As a result, new policy efforts are being directed towards opioid use disorders (Blendon, McMurtry, Benson, & Sayde, 2016; Office of the Press Secretary, 2016) and the number of evidence-based therapies to address opioid use disorders is increasing (Amato et al., 2005; Brooks et al., 2010; Campbell et al., 2012; Carpenter et al., 2009; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2014; Sullivan et al., 2006). Treatment programs are increasingly adopting many of these therapies (Andrews, D’Aunno, Pollack, & Friedmann, 2014) and program evaluations suggest they are effective in helping clients achieve and maintain abstinence (Sheehan, Oppenheimer, & Taylor, 1993; Wittchen et al., 2008).

Yet abstinence from opioids is not the only relevant outcome of opioid use disorder treatment. Many policy makers view health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and quality adjusted life years (QALYs) as important treatment outcomes and as critical inputs for decision-making, particularly for economic evaluations such as cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs). The US Food and Drug Administration encourages the use of patient-reported outcome measures, a group of outcomes that includes validated HRQoL measures. Several non-profit organizations and professional societies in the US have recently introduced initiatives to measure the value of prescription drugs via CEAs that use QALYs (Neumann & Cohen, 2015). Despite controversy in the US surrounding the use of QALYs in economic evaluations (Neumann & Weinstein, 2010), the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is charged with reviewing “…the scientific evidence related to the effectiveness, appropriateness, and cost-effectiveness of clinical preventive services… [emphasis added]” when it ranks preventive services (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2015). Furthermore, the USPSTF lists HRQoL as a relevant health outcome and QALYs as a measure of disease burden (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2015). The US Medicare program also considers CEA evidence when determining coverage for preventive services (Chambers, Cangelosi, & Neumann, 2015).

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) explicitly includes CEA considerations in its development of clinical guidelines and requires the use of QALYs in CEA (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013). NICE also requires that the evidence is relevant to the patient populations that will be treated, which supports the need for treatment programs to collect HRQoL. For example, in its review of CEA evidence in support of methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence, NICE states that “Although most of the included papers were considered to be of high quality, none used all of the appropriate parameters, effectiveness data, perspectives and comparators required to make their results generalisable to the NHS and personal social services (PSS)” (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2007).

In light of the increased policy focus on opioid use disorder treatment and the importance to policy makers of HRQoL as a health outcome measure, we contend that opioid treatment programs should routinely collect HRQoL as a standard measure of treatment outcome, and should use an HRQoL measure that can be used to calculate QALYs. Measuring HRQoL in opioid use disorder treatment programs represents an opportunity to consider outcomes that are more patient-centered and more relevant to overall health than abstinence alone, and to expand the definition of treatment benefits. Some clinical trials of opioid use disorder therapies measure HRQoL outcomes, and in particular QALYs, so that economic outcomes can be compared to those from studies of other health conditions (Byford et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2012; Nosyk et al., 2011; Polsky et al., 2010). Measurement of these patient-centered and economic outcomes in “real world” program settings is also needed to support greater adoption of evidence-based services.

We conducted a systematic review of the opioid use disorder treatment program literature to explore the extent to which the reporting of HRQoL and/or QALYs by treatment programs is documented in the literature. We therefore focused our review on studies reporting data collected from extant, fully operational opioid treatment programs. Given the current opioid epidemic and resulting policy attention, we focus our review solely on opioids and do not consider other substances to better inform the responses to the current opioid-related public health crisis. We report the results of this systematic review and conclude with a discussion of how HRQoL and QALYs can be effectively incorporated into treatment program quality metrics.

2. Materials & methods

We conducted a systematic review to identify published studies that reported any quality of life (QoL) measure (encompassing but broader than HRQoL measures) as an outcome of substance abuse treatment programs. Systematic review procedures were conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009).

We searched PubMed, Embase PsycINFO and Web of Science between June 2014 and July 2015 for published papers reporting QoL outcome measures of substance abuse treatment programs. To capture grey literature such as government reports, working papers, and presentations, we searched conferences and meetings in Web of Science and we searched the New York Academy of Medicine’s Grey Lit Report. We identified the broadest search terms relevant to our goals and used database-specific search terms reflecting the search term mapping of each database. PubMed MeSH terms and Boolean connectors included ‘opioid-related disorders OR drug users’ AND ‘substance abuse treatment centers OR community health centers OR therapeutic community’ AND ‘incidence OR follow-up studies OR mortality’. Embase Thesaurus descriptors used included: ‘opiate addiction OR drug dependence’ AND ‘rehabilitation centers OR therapeutic community’ AND ‘incidence OR follow-up OR mortality’. PsycINFO Thesaurus descriptors used included: ‘drug usage OR drug addiction OR opiates’ AND ‘rehabilitation centers OR therapeutic community’ AND ‘followup studies OR prediction OR mortality’. Natural language searching in Web of Science consisted of the following: ‘opiate addiction or drug addict or drug dependence’ AND ‘drug rehab center OR rehabilitation center OR community health center OR therapeutic community’ AND ‘incidence OR follow up studies OR follow up OR prediction OR (prediction AND forecasting) OR mortality.’

Articles were screened by one co-author and review-relevant information on each was entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2013). Information collected on screened articles included: country in which the treatment program was located; type of study (e.g., observational); primary substance studied (e.g., heroin); type of substance use disorder treatment, classified as methadone, buprenorphine (Subutex), buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone), medical or psychiatric care, and behavioral therapies including counseling and group therapy; HRQoL outcome measures reported, including reporting of QALYs or health utilities; additional treatment-related outcomes reported (e.g., abstinence); and any other social or psychosocial well-being measures reported (e.g. family support status, mental health status, housing status, etc.).

Articles were included in full-text review if they described heroin, prescription opioid, or a combination of heroin and prescription opioid use and described QoL measures as a treatment program outcome. The review of full-text articles was conducted by three co-authors: one coauthor reviewed all articles and two co-authors each reviewed one-half of all articles. Articles selected for full-text review were subsequently excluded if they did not report QoL results, did not have an abstract available in English, were a review article, or reported results from a randomized control trial. We excluded articles reporting trial results because these studies likely do not report data being collected routinely by the involved treatment programs.

Included articles were qualitatively analyzed for their use of HRQoL measures. Included articles were classified as including a validated non-health-related quality of life (QoL) measure or another HRQoL/ QoL measure. Studies classified as using validated HRQoL measures were sub-classified as to whether they used measures that can be transformed into QALYs (e.g., SF-12, SF-36, or EQ-5D) (Brazier, Roberts, & Deverill, 2002; Brazier & Roberts, 2004; Shaw, Johnson, & Coons, 2005). We defined validated HRQol/QoL measures as those that encompass multiple facets of an individual’s perceived physical and mental health and have a peer-reviewed validation study that was published separately from the article under review.

3. Results

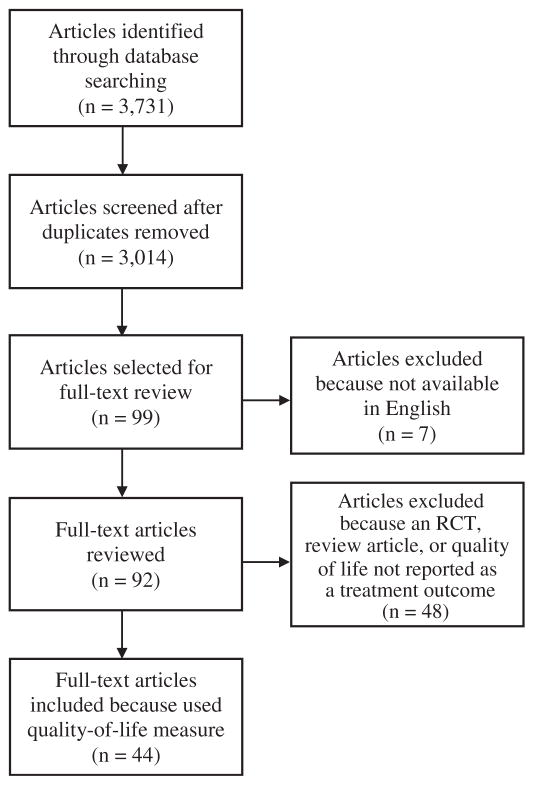

Fig. 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for our review. A total of 3731 papers were identified electronically. After removing duplicates, abstracts for 3014 articles were screened for inclusion. Of those, 99 articles were identified as potentially including QoL measures, 7 of which were excluded because they were not available in English. The full-text of the remaining 92 articles was reviewed. Of those, 39 were excluded because they did not include QoL as a treatment outcome measure, 7 were excluded that described clinical trial results only, and 2 were excluded that were review articles, leaving 44 articles included in the subsequent analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included articles compared to the complete set of articles identified. Among the 3014 articles initially identified, more than two-thirds were published since 2000 and less than one-third were published between 1965 and 1999. Among articles that use a QoL measure, approximately 80% were published since 2000. Among all articles identified, nearly two-thirds were from the US or Canada, with another quarter coming from Europe. In comparison, well under half (n = 17) of treatment programs in the studies that included a QoL measure were located in the US or Canada. Europe was the next most frequent region with 11 articles, followed by Asia/Middle East with 9 articles, Australia/New Zealand with 6 articles and the Caribbean with 1 article.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected articles with quality of life measure compared to all articles.

| Characteristic | Literature review articles (n = 3014) | Selected articles with quality of life measure (n = 44) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Year of publication | ||||

| 1965–1984 | 140 | 4.6 | 2 | 4.5 |

| 1985–1989 | 80 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1990–1994 | 373 | 12.4 | 4 | 9.1 |

| 1995–1999 | 341 | 11.3 | 3 | 6.8 |

| 2000–2004 | 562 | 18.6 | 5 | 11.4 |

| 2005–2009 | 828 | 27.5 | 20 | 45.5 |

| 2010–2015 | 690 | 22.9 | 10 | 22.7 |

| Origin of study | ||||

| US/Canada | 1862 | 61.8 | 17 | 38.6 |

| Europe | 742 | 24.6 | 11 | 25.0 |

| Asia/Middle East | 170 | 5.6 | 9 | 20.5 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 161 | 0.4 | 6 | 13.6 |

| South American/Caribbean/Mexico | 28 | 5.3 | 1 | 2.3 |

| Africa | 12 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 39 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2 summarizes the use of QoL measures among the 44 included articles and presents the primary author, the year of publication, country of the opioid treatment program under study, and whether the treatment program included opioid substitution treatment (OST; including methadone, buprenorphine, or buprenorphine/naloxone). Thirty-two articles reported data on treatment programs that included OST. Seventeen of the articles used validated measures of HRQoL. Ten of these articles used HRQoL measures that can be used to derive QALYs. Of these, 8 used the SF-12 and 3 used the SF-36. None of these 10 articles reported QALY results. Only 3 of these articles were from the US, despite the US accounting for more than half of all articles screened. Other validated HRQoL measures used include the Q-LES-Q (n = 2), WHOQOL-BREF (n = 1), MSQoL (n = 1), McGill QOL (n = 1), HRQolDA (n = 1) and a measure developed specifically to measure HRQoL among individuals with substance use disorders in China (n = 2). Additional QoL measures that did not specifically measure HRQoL include the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1992) or adaptations thereof (n = 14), Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) (Derogatis, Lipman, & Covi, 1973) (n = 6), and a variety of QoL measures each used by a single article (n = 7). Half of all articles using the ASI were from the US (n = 7); all other QoL measures were relatively evenly spread across countries.

Table 2.

Summary of articles with quality of life measure.

ASI = Addiction Severity Index; HRQOL = health-related quality-of-life; OST = opioid substitution treatment; QoL = quality of life.

4. Discussion

We conducted a systematic literature review of studies of opioid use disorder treatment programs and screened over 3000 English-language articles published between 1965 and 2015. We found that the use of validated HRQoL measures in published literature on opioid use disorder treatment programs is rare, and HRQoL measures that can be used to derive QALYs are almost never used. Of the articles that reported HRQoL measures that would support QALYs, most reported data from treatment programs not located in the US. The most frequently used validated measure was the ASI, which does not include a composite score for HRQoL (McLellan et al., 1992).

Our finding that assessments of HRQoL are rare in the opioid use disorder treatment literature is confirmed by a related systematic review that compared studies reporting the QoL of opiate-dependent individuals and assessed the QoL instruments used (De Maeyer, Vanderplasschen, & Broekaert, 2010). In their review, De Maeyer and colleagues retrieved only 127 articles, 38 of which met their review inclusion criteria, leading them to conclude that opioid research with a primary focus on QoL is limited. Although our review and that of De Maeyer and colleagues both examine QoL and opioid use disorders, they employed different objectives and search criteria resulting in little overlap in the articles identified by the two reviews (only 5 articles were included in both). Nonetheless, the review by De Maeyer and colleagues supports our conclusion that the reporting of QoL in the opioid treatment literature is rare.

Despite our finding of little evidence that treatment programs collect HRQoL measures, we contend that collecting these measures is nonetheless feasible and practicable. Given the data collection burden associated with the lengthy ASI, a measure that was collected by far more treatment programs than were HRQoL measures, collecting short HRQoL measures such as the 12-item SF-12 or 6-item EQ-5D should be feasible for most treatment programs. Concerns that generic HRQoL measures may not be appropriate for opioid using populations are contradicted by findings that many such measures are sensitive to changes in opioid use (Nosyk et al., 2010) and that they capture treatment-related changes in HRQoL (De Maeyer et al., 2010; Nosyk et al., 2015). Given the growing importance of patient reported outcomes and cost-effectiveness analysis, the benefits of collecting such short instruments likely outweighs the costs for most opioid treatment programs.

Our review is subject to limitations. We purposely excluded publications reporting clinical trial results because our intent was to assess the extent to which extant treatment programs report HRQoL data—data that could provide evidence relevant to decision makers evaluating the effectiveness of treatment for specific populations. In our effort to focus on “real world” settings, we may have missed some studies that reported data from treatment programs but did not meet our search terms. In particular, we find it somewhat surprising that we found no studies reporting use of the GAIN, despite its widespread use in US adolescent treatment studies (Dennis, Titus, White, Unsicker, & Hodgkins, 2008).

We believe the opioid use disorder treatment field should incorporate HRQoL measures and the assessment of QALYs as standard practice, both to provide policy makers with evidence that supports the impact of programs on patients’ lives and to provide data to support cost-effectiveness evaluations that quantify the value of investing in opioid use disorder treatments. A potential barrier to achieving this goal is that programs may be required to pay licensing fees to use some of the current standard measures, although fees may be discounted for non-commercial users. Alternative HRQoL measures are available without cost from the World Health Organization and the National Institutes of Health PROMIS initiative (Hays, Bjorner, Revicki, Spritzer, & Cella, 2009), but there is not yet an accepted approach to using these measures to calculate QALYs (Hanmer et al., 2015). The lack of HRQoL evidence prevents opioid treatment programs from assessing the full impact of treatment on patients’ lives and limits their ability to fully capture the value of investments in opioid use disorder treatments. We advocate for the development of publicly available, validated HRQoL measures and associated health utilities that opioid use disorder treatment programs can routinely collect.

Adopting opioid use disorder treatment outcomes that extend beyond abstinence to assess HRQoL outcomes will require changing attitudes among treatment programs and the payers to whom they are accountable. The task will become easier as there is greater recognition that opioid use disorder is a chronic disease requiring continuing care, and as opioid use treatment programs are more fully integrated into healthcare delivery systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephanie Norris, MA and Megan Braunlin, MPH for research assistance. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant numbers R01DA033424 and P30DA040500].

References

- Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci CA, Ferri M, Faggiano F, Mattick RP. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: Available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM, D’Aunno TA, Pollack HA, Friedmann PD. Adoption of evidence-based clinical innovations: The case of buprenorphine use by opioid treatment programs. Medical Care Research and Review. 2014;71(1):43–60. doi: 10.1177/1077558713503188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077558713503188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astals M, Domingo-Salvany A, Buenaventura CC, Tato J, Vazquez JM, Martin-Santos R, Torrens M. Impact of substance dependence and dual diagnosis on the quality of life of heroin users seeking treatment. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43(5):612–632. doi: 10.1080/10826080701204813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R, McMurtry C, Benson J, Sayde J. the opioid abuse crisis is a rare area of Bipartisan consensus. 2016 Retrieved from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/09/12/the-opioid-abuse-crisis-is-a-rare-area-of-bipartisan-consensus/

- Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21(2):271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. S0167-6296(01)00130-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Medical Care. 2004;42(9):851–859. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d. 00005650-200409000-00004 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AC, Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Bisaga A, Carpenter KM, Raby WM, … Nunes EV. Long-acting injectable versus oral naltrexone maintenance therapy with psychosocial intervention for heroin dependence: A quasi-experiment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1371–1378. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05080ecr. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05080ecr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byford S, Barrett B, Metrebian N, Groshkova T, Cary M, Charles V, … Strang J. Cost-effectiveness of injectable opioid treatment v. oral methadone for chronic heroin addiction. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;203(5):341–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.111583. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.111583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Miele GM, Matthews A, Polsky D, Ghitza UE, … Crowell AR. Design and methodological considerations of an effectiveness trial of a computer-assisted intervention: An example from the NIDA clinical trials network. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2012;33(2):386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Jiang H, Sullivan MA, Bisaga A, Comer SD, Raby WN, … Nunes EV. Betting on change: Modeling transitional probabilities to guide therapy development for opioid dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):47–55. doi: 10.1037/a0013049. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JD, Cangelosi MJ, Neumann PJ. Medicare’s use of cost-effectiveness analysis for prevention (but not for treatment) Health Policy. 2015;119(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J, Williamson A, Mills KL, Havard A, Teesson M. Patterns and correlates of attempted suicide by heroin users over a 3-year period: Findings from the Australian treatment outcome study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87(2–3):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maeyer J, Vanderplasschen W, Broekaert E. Quality of life among opiate-dependent individuals: A review of the literature. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2010;21(5):364–380. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.01.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maeyer J, Vanderplasschen W, Lammertyn J, van Nieuwenhuizen C, Broekaert E. Exploratory study on domain-specific determinants of opiate-dependent individuals’ quality of life. European Addiction Research. 2011;17(4):198–210. doi: 10.1159/000324353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000324353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White M, Unsicker J, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. 2008 Retrieved from Bloomington, IL: http://www.gaincc.org/GAINI.

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale—preliminary report. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1973;9(1):13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed A, Casarella J, Amar R, Vayalapalli S, Drexler K. Benefits of retention in methadone maintenance and chronic medical conditions as risk factors for premature death among older heroin addicts. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2009;15(3):227–234. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000351884.83377.e2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000351884.83377.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassino S, Daga GA, Delsedime N, Rogna L, Boggio S. Quality of life and personality disorders in heroin abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Saiz F, Gomez RB, Acedos IB, Rojas OL, Ortega JG. Methadone-treated patients after switching to buprenorphine in residential therapeutic communities: An addiction-specific assessment of quality of life. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2009;11(2):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hanmer J, Feeny D, Fischhoff B, Hays RD, Hess R, Pilkonis PA, … Yu L. The PROMIS of QALYs. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:122. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0321-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havard A, Teesson M, Darke S, Ross J. Depression among heroin users: 12-month outcomes from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(4):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Hall SM, Wasserman DA. Social support and relapse: Commonalities among alcoholics, opiate users, and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16(5):235–246. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(7):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Kagihara J, Huang D, Evans E, Messina N. Mortality among substance-using mothers in California: A 10-year prospective study. Addiction. 2012;107(1):215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03613.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson I, Hesse M, Fridell M. Personality disorder features as predictors of symptoms five years post-treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(3):172–175. doi: 10.1080/10550490802019725. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10550490802019725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, Broome KM. Effects of readiness for drug abuse treatment on client retention and assessment of process. Addiction. 1998;93(8):1177–1190. doi: 10.1080/09652149835008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SY, Deren S, Goldstein MF. Relationships between childhood abuse and neglect experience and HIV risk behaviors among methadone treatment dropouts. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26(12):1275–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Winter MR, Safran DG, Saitz R. Primary care quality and addiction severity: A prospective cohort study. Health Services Research. 2007;42(2):755–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00630.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko NY, Wang PW, Wu HC, Yen CN, Hsu ST, Yeh YC, … Yen CF. Self-efficacy and HIV risk behaviors among heroin users in Taiwan. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(3):469–476. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang MA, Belenko S. Predicting retention in a residential drug treatment alternative to prison program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19(2):145–160. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Bowen S, Oei TP, Yen CF. An expanded self-medication hypothesis based on cognitive-behavioral determinants for heroin abusers in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(Suppl 1):S43–S48. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00301.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, Brooner RK, Bigelow GE, Kindbom K, Strain EC. Characteristics of older opioid maintenance patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;2:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Childress AR, Griffith J, Woody GE. The psychiatrically severe drug abuse patient: Methadone maintenance or therapeutic community? The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1984;10(1):77–95. doi: 10.3109/00952998409002657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, … Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Lin MM, Brown LS., Jr Nicotine dependence and depression among methadone maintenance patients. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1996;88(12):800–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on treatment outcomes for heroin dependence. Addiction. 2007;102(3):447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01711.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The costs and outcomes of treatment for opioid dependence associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):940–945. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. (W264) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moylan PL, Jones HE, Haug NA, Kissin WB, Svikis DS. Clinical and psychosocial characteristics of substance-dependent pregnant women with and without PTSD. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(3):469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. 2007 Retrieved from London, United Kingdom: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta114.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of tecnology appraisal 2013. 2013 Retrieved from London, United Kingdom: https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf. [PubMed]

- Neumann PJ, Cohen JT. Measuring the value of prescription drugs. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(27):2595–2597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1512009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC. Legislating against use of cost-effectiveness information. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(16):1495–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1007168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1007168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Bray J, Wittenberg E, Aden B, Eggman A, Weiss R, … Ling W. Short term health-related quality of life improvement during opioid agonist treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;157:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Guh DP, Sun H, Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, … Anis AH. Health related quality of life trajectories of patients in opioid substitution treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(2–3):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Sun H, Guh DP, Oviedo-Joekes E, Marsh DC, Brissette S, … Anis AH. The quality of eight health status measures were compared for chronic opioid dependence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(10):1132–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Press Secretary TWH. President Obama proposes $1.1 billion in new funding to address the prescription opioid abuse and heroin use epidemic. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 2016;30(2):134–137. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2016.1173760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Schreiber S, Adelson M. 15-year survival and retention of patients in a general hospital-affiliated methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) center in Israel. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;107(2–3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polsky D, Glick HA, Yang J, Subramaniam GA, Poole SA, Woody GE. Cost-effectiveness of extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for opioid-dependent youth: Data from a randomized trial. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1616–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03001.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponizovsky AM, Grinshpoon A. Quality of life among heroin users on buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(5):631–642. doi: 10.1080/00952990701523698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00952990701523698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponizovsky AM, Margolis A, Heled L, Rosca P, Radomislensky I, Grinshpoon A. Improved quality of life, clinical, and psychosocial outcomes among heroin-dependent patients on ambulatory buprenorphine maintenance. Substance Use & Misuse. 2010;45(1–2):288–313. doi: 10.3109/10826080902873010. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826080902873010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam R, Sivesind D, Todman M, Roane D, Seewald R. The aging methadone maintenance patient: Treatment adjustment, long-term success, and quality of life. Journal of Opioid Management. 2009;5(1):27–37. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao R, Ambekar A, Yadav S, Sethi H, Dhawan A. Slow-release oral morphine as a maintenance agent in opioid dependence syndrome: An exploratory study from India. Journal of Substance Use. 2012;17(3):294–300. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2011.583310. [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Amundsen EJ. Mortality among drug users after discharge from inpatient treatment: An 8-year prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1–2):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P. Self-reported depression as a predictor of dropout in a hierarchical therapeutic community. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P. Overdoses and suicide attempts: different relations to psychopathology and substance abuse? A 5-year prospective study of drug abusers. European Addiction Research. 1999;5(2):63–70. doi: 10.1159/000018967. (doi:18967) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P, Lauritzen G. Completion of long-term inpatient treatment of drug abusers: A prospective study from 13 different units. European Addiction Research. 2005;11(4):180–185. doi: 10.1159/000086399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000086399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick RB, Resnick E, Galanter M. Buprenorphine responders: A diagnostic subgroup of heroin addicts? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 1991;15(4):531–538. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(91)90028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D, Smith ML, Reynolds CF., 3rd The prevalence of mental and physical health disorders among older methadone patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):488–497. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff35a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Crits-Christoph K, Wilber C, Kleber H. Diagnosis and symptoms of depression in opiate addicts. Course and relationship to treatment outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39(2):151–156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290020021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan-Szal GA, Chatham LR, Joe GW, Simpson DD. Services provided during methadone treatment. A gender comparison. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden MR. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. American Journal of Transplantation. 2016;16(4):1323–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: Development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Medical Care. 2005;43(3):203–220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003. (doi:00005650-200503000-00003 [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan M, Oppenheimer E, Taylor C. Opiate users and the first years after treatment: Outcome analysis of the proportion of follow up time spent in abstinence. Addiction. 1993;88(12):1679–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Gainey RR. Opiate-addicted parents in methadone treatment: Long-term recovery, health, and family relationships. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2011;30(1):17–26. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.531670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2010.531670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Trader A, Klotsche J, Haberthur A, Buhringer G, Rehm J, Wittchen HU. Criminal behavior in opioid-dependent patients before and during maintenance therapy: 6-year follow-up of a nationally representative cohort sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2012;57(6):1524–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02234.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MA, Rothenberg JL, Vosburg SK, Church SH, Feldman SJ, Epstein EM, … Nunes EV. Predictors of retention in naltrexone maintenance for opioid dependence: Analysis of a stage I trial. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15(2):150–159. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10550490500528464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Havard A, Ross J, Darke S. Outcomes after detoxification for heroin dependence: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25(3):241–247. doi: 10.1080/09595230600657733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09595230600657733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Procedure manual. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFile/6/7/procedure-manual_2016_v2/pdf.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report. 2015. (Retrieved from Vienna, Austria) [Google Scholar]

- Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Haasen C, Krausz M. Significance of comorbidity for the long-term course of opiate dependence. European Addiction Research. 2005;11(1):15–21. doi: 10.1159/000081412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000081412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A, Darke S, Ross J, Teesson M. Changes and predictors of change in the physical health status of heroin users over 24 months. Addiction. 2009;104(3):465–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02475.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Apelt SM, Soyka M, Gastpar M, Backmund M, Golz J, … Buhringer G. Feasibility and outcome of substitution treatment of heroin-dependent patients in specialized substitution centers and primary care facilities in Germany: A naturalistic study in 2694 patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(3):245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Management of substance abuse: Information sheet on opioid overdose. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/information-sheet/en/

- Xiao L, Wu Z, Luo W, Wei X. Quality of life of outpatients in methadone maintenance treatment clinics. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53(Suppl 1):S116–S120. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7dfb5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7dfb5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Wu Z, Wang Y, Chen J. Comparison of quality of life for drug addicts in methadone maintenance treatment clinics, community and compulsory detoxification institutions in Sichuan Province. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2009;38(1):67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]