Abstract

Background:

Our review question was “Does perioperative steroids administration, in comparison with other treatments or placebo, improve either postoperative pain control, length of hospital stay, or return to work in patients undergoing lumbar disc surgery?”

Methods:

We searched PubMed, CINAHL PLUS, and Cochrane databases for randomized control trials (RCTs) studying the role of steroids for lumbar disc surgery. Studies that compared perioperative steroids with other treatments or placebo were included. Study outcomes included postoperative back pain, leg pain, length of hospital stay, and return to work. Data was extracted through a proforma. Means and mean differences were calculated for continuous data, whereas odds ratios were calculated for dichotomous data. Data were analyzed with the help of Rev Man 5.

Results:

Twenty RCTs were included in the review. Quantitative analysis could be performed on 19 RCTs. Intraoperative steroids improve control of back pain at 24–48 hours. Although there was some benefit of steroid administration in controlling postoperative leg pain, it disappeared at 1 year and in the overall pooled analysis. The length of hospital stay was much shorter in the steroid group. The frequency of adverse events and complications also favored steroid administration.

Conclusion:

Intraoperative epidural steroid administration offers some benefit in pain control with a significant reduction in the length of hospital stay. However, there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of oral and intravenous steroids in the perioperative period.

Keywords: Lumbar surgery, lumbar surgery outcomes, microdiscectomy, perioperative steroids, randomized control trials

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of lumbosacral radiculopathy is estimated to be approximately 3–5%, and therefore, lumbar disc surgery is one of the most common procedures performed by spine surgeons in United States[17,18] Because radicular pain may be partially attributed to inflammatory mediators, some surgeons have utilized perioperative steroids[8] (e.g., strong anti-inflammatory effect, modulation of pain receptors).[8] Here, we reviewed the current randomized controlled trial (RCT) literature regarding the use of perioperative steroids in lumbar disc surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included an analysis of RCT studies for adult patients undergoing surgery for lumbar disc herniation who received preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative steroids, administered through any route, i.e., oral, intravenous, or epidural. We searched PubMed, CINAHL PLUS, and Cochrane databases for randomized control trials (RCTs) studying the role of steroids for lumbar disc surgery. A detailed search strategy is given in Appendix 1. We identified the differences in the mean pain scores [e.g., visual analog scale (VAS) at 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year], mean length of hospital stay (LOS), mean number of days to return to work, and the percentage of adverse events (AE) in patients receiving perioperative steroids vs. control patients (who received no steroids).

Data extraction

Two reviewers separately and independently extracted the data, which was then recorded in Microsoft Excel. In cases where desired data was not reported by authors, the corresponding authors were contacted for more details or missing data.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed for each of the selected RCT on six quality parameters, i.e., comparability of treatment groups, standardization of care protocol, blinding of care, adequacy of outcomes, blinding of outcomes, and completeness of follow-up. Each parameter was given a score of 1-point if it was adequately described in the article. No score was given for absence of quality parameter or inadequate description of the same. Study quality level was obtained by adding the scores of each parameter to grade the studies from a total of 6 points.

RESULTS

Twenty RCTs were included in this systematic review, and quantitative analysis was performed on 19 studies [Table 1]. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart – study selection

Two RCTs by Ludin et al.[12] and Hurlbert et al.[10] had maximum quality level of 6, whereas RCT by Debi et al.[5] showed the lowest quality score of 1. Most studies had quality level of 3 or 4. Summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of methods and clinical characteristic of studies include in the review

Postoperative back pain

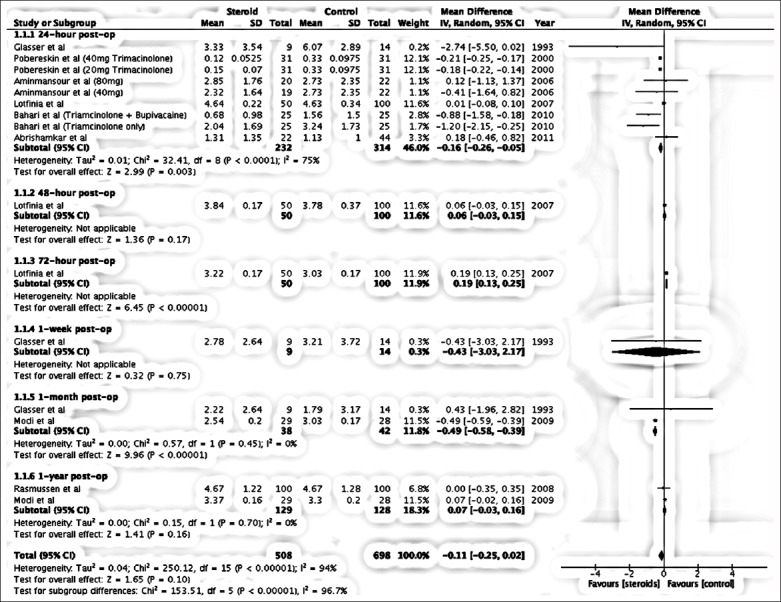

Six studies assessed postoperative back pain at 24 hours. The analysis favored the use of steroids, with a mean difference of −0.16 [95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.26, −0.05]. This difference was statistically significant with a P value of 0.003 [Figure 2]. Analysis showed similar trend at 1 month and for overall analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot – meta-analysis of postoperative back pain

Postoperative leg pain

The overall analysis favored the use of epidural steroids for reduction of leg pain. The analysis showed significant pain reduction with epidural steroids at 1 week and 1 year. The overall effect favored steroid group with mean difference of −0.18 (−0.29, −0.07). Test for effect Z was 3.32 (P value = 0.001).

Length of hospital stay

The overall mean difference on LOS favored steroid group with a value of –0.93 (−1.31, −0.55), with a P value of 0.00001.

Return to work

The mean number of days for return to work favored the steroid group with a mean difference of –2.90 (95% CI − 3.94, −1.86).

Adverse events

Fifteen RCTs reported AEs and an odds ratio of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.41, 1.26) favored steroid group [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Forest plot – meta-analysis of adverse effects

DISCUSSION

Perioperative steroids better control back and leg pain. The administration of perioperative steroids resulted in improved postoperative back pain and postoperative leg pain. The overall mean difference in postoperative back pain between the two groups was small and not statistically significant, i.e., –0.11 (CI − 0.25, 0.02), with a P value of 0.1. RCTs by Pobereskin et al.,[14] Bahari et al.,[4] and Aminmansour et al.[3] had two intervention groups assessing different regimens of steroids in comparison to controls. Each of the regimens by these three trials were analyzed separately [Figure 2]. Only one study by Lutfina et al.[11] assessed postoperative back pain at 48 and 72 hours, with a mean difference of +0.06 and +0.19 favoring control groups. One RCT by Glasser et al. assessed postoperative back pain at one week with a mean difference of −0.43 (CI = −3.03, 2.17). The overall effect Z was 0.32 (P value = 0.75). Two RCTs by Glasser et al.[7] and Modi et al.[13] assessed postoperative back pain at 1 month, with a mean difference of −0.49 (CI = −0.58, −0.39) favoring steroid group. Two RCTs by Rasmussen et al.[16] and Modi et al.[13] assessed postoperative back pain at 1 year, with a mean difference 0.07 (CI = −0.03, 0.16).

Analysis favored the steroid group for better postoperative leg pain control at 1 week and 1 year postoperatively [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Forest plot – meta-analysis of postoperative leg pain

RCT by Aminmansour et al.[3] studied two steroid regimens, which we analyzed separately. Mean difference was −0.19 (CI = −0.42, 0.04). Overall effect Z was 1.59 (P value = 0.11). Three RCTs assessed postoperative leg pain at 48 hours. Mean difference between steroid and control group was 0.07 (CI = −0.30, 0.45). The effect Z was 0.39 (P value = 0.70). Three RCTs assessed postoperative leg pain at 1 week, with a mean difference of −0.05 (−0.07, −0.03). Test for overall effect Z was 4.25 with a significant P value of <0.001. Mean differences for postoperative leg pain at 72 hours and 1 month were not statistically significant between the groups. Rasmussen et al. assessed postoperative leg pain at 1 year, with a mean difference of –2.33 (CI = −2.58, −2.08).

Perioperative steroids reduce length of stay

Patients receiving perioperative steroids exhibited shorter LOS. Eight of the nine RCTs included in analysis showed shorter hospital stay in steroid group with mean difference of −0.93 (−1.31, −0.55) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Forest plot – meta-analysis of total hospital length of stay

Perioperative steroids reduced time to return to work

Only one RCT by Aljabi et al.[2] evaluated time for return to activity and favored steroid group [Figure 6]. Fifteen RCTs did not show an increase in adverse events for patients receiving steroid (e.g., indicating the safety of epidural steroids in surgery). However, there were considerable differences in what was defined as an adverse event by different RCTs.

Figure 6.

Forest plot – meta-analysis of return to work

Quality of randomized controlled trials

The quality of RCTs was assessed using a standardized 6-point scale specifically designed for systematic reviews. Only three RCTs conducted by investigators Diaz,[6] Hurlbert,[10] and Lundin et al.[12] had the maximum score. Another limitation of the RCTs was heterogeneity of outcomes. Most RCTs focused on short-term control of back and leg pain, and only two RCTs by Rasmussen et al.[16] and Modi et al.[13] assessed pain control at 1 year. Moreover, the method of reporting different variables also varied between different RCTs. For numerical data, some trials reported medians, which required conversion into means for analysis. This statistical problem was solved with the help of Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and article by Hozo.[9,18]

Previous systematic reviews on the topic had several limitations. The review by Ranguis et al. in 2010 missed several key trials[15] and did not distinguish microdiscectomy from laminectomy, which are two different procedures. It also did not analyze steroids administered intravenously or in oral form. Another review by Akinduro et al.[1] only examined the complications related to steroid use[1] addressing postoperative pain as a secondary outcome with no meta-analysis.

CONCLUSION

Intraoperative epidural steroid administration offers some benefit in pain control with a significant reduction in LOS. However, there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of oral and intravenous steroids in the perioperative period.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1: SEARCH STRATEGY

NLM PubMed:

((“lumbar disc surgery”[All Fields] AND ((“prednisolone”[MeSH Terms] OR “prednisolone”[All Fields]) OR (“methylprednisolone”[MeSH Terms] OR “methylprednisolone”[All Fields]) OR (“dexamethasone”[MeSH Terms] OR “dexamethasone”[All Fields]))) OR (“lumbar disc surgery”[All Fields] AND ((“postoperative period”[MeSH Terms] OR (“postoperative”[All Fields] AND “period”[All Fields]) OR “postoperative period”[All Fields] OR (“post”[All Fields] AND “operative”[All Fields]) OR “post operative”[All Fields]) OR (“postoperative period”[MeSH Terms] OR (“postoperative”[All Fields] AND “period”[All Fields]) OR “postoperative period”[All Fields] OR “postoperative”[All Fields])))) OR (((“lumbosacral region”[MeSH Terms] OR (“lumbosacral”[All Fields] AND “region”[All Fields]) OR “lumbosacral region”[All Fields] OR “lumbar”[All Fields]) AND disc[All Fields] AND (“surgery”[Subheading] OR “surgery”[All Fields] OR “surgical procedures, operative”[MeSH Terms] OR (“surgical”[All Fields] AND “procedures”[All Fields] AND “operative”[All Fields]) OR “operative surgical procedures”[All Fields] OR “surgery”[All Fields] OR “general surgery”[MeSH Terms] OR (“general”[All Fields] AND “surgery”[All Fields]) OR “general surgery”[All Fields])) AND (“steroids”[MeSH Terms] OR “steroids”[All Fields]))) OR (“lumbar disc surgery”[All Fields] AND (“pain”[MeSH Terms] OR “pain”[All Fields]))

-

CENTRAL (Cochrane)

- Lumbar disc surgery AND steroid

-

CINAHL PLUS (EBSCOHOST)

- Lumbar disc surgery AND steroid

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Muhammad Waqas, Email: shaiq_waqas@hotmail.com.

Hussain Shallwani, Email: hshallwani1@gmail.com.

Muhammad S. Shamim, Email: shahzad.shamim@aku.edu.

Khabir Ahmad, Email: khabir.ahmad@aku.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akinduro OO, Miller BA, Haussen DC, Pradilla G, Ahmad FU. Complications of intraoperative epidural steroid use in lumbar discectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E12. doi: 10.3171/2015.7.FOCUS15269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aljabi Y, El-Shawarby A, Cawley DT, Aherne T. Effect of epidural methylprednisolone on post-operative pain and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing lumbar microdiscectomy. Surgeon. 2015;13:245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aminmansour B, Khalili HA, Ahmadi J, Nourian M. Effect of high-dose intravenous dexamethasone on postlumbar discectomy pain. Spine. 2006;31:2415–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000238668.49035.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahari S, El-Dahab M, Cleary M, Sparkes J. Efficacy of triamcinolone acetonide and bupivacaine for pain after lumbar discectomy. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1099–103. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debi R, Halperin N, Mirovsky Y. Local application of steroids following lumbar discectomy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:273–6. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz RJ, Myles ST, Hurlbert RJ. Evaluation of epidural analgesic paste components in lumbar decompressive surgery: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:414–24. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182315f05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasser RS, Knego RS, Delashaw JB, Fessler RG. The perioperative use of corticosteroids and bupivacaine in the management of lumbar disc disease. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:383–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.3.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grönblad M, Virri J, Tolonen J, Seitsalo S, Kääpä E, Kankare J, et al. A controlled immunohistochemical study of inflammatory cells in disc herniation tissue. Spine. 1994;19:2744–51. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hozo S, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Method. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurlbert RJ, Theodore N, Drabier JB, Magwood AM, Sonntag VK. A prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of an analgesic epidural paste following lumbar decompressive surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 1999;90:191–7. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.90.2.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotfinia I, Khallaghi E, Meshkini A, Shakeri M, Shima M, Safaeian A. Interaoperative use of epidural methylprednisolone or bupivacaine for postsurgical lumbar discectomy pain relief: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:279. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundin A, Magnuson A, Axelsson K, Kogler H, Samuelsson L. The effect of perioperative corticosteroids on the outcome of microscopic lumbar disc surgery. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:625–30. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0554-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modi H, Chung KJ, Yoon HS, Yoo HS, Yoo JH. Local application of low-dose Depo-Medrol is effective in reducing immediate postoperative back pain. Int Orthop. 2009;33:737–43. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pobereskin L, Sneyd J. Does wound irrigation with triamcinolone reduce pain after surgery to the lumbar spine? Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:731–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranguis SC, Li D, Webster AC. Perioperative epidural steroids for lumbar spine surgery in degenerative spinal disease: A review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:745–57. doi: 10.3171/2010.6.SPINE09796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen S, Krum-Møller DS, Lauridsen LR, Jensen SEH, Mandøe H, Gerlif C, et al. Epidural steroid following discectomy for herniated lumbar disc reduces neurological impairment and enhances recovery: A randomized study with two-year follow-up. Spine. 2008;33:2028–33. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181833903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:387–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson AN, Blood E, Abdu WA, et al. Surgical versus non-operative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: Four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2008;33:2789. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ed8f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]