Abstract

Objective

To determine whether measures of heart rate variability (HRV) are related to changes in temperature during rewarming after therapeutic hypothermia (TH) for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE).

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Level 4 neonatal intensive care unit in a free-standing academic children's hospital.

Patients

Forty-four infants with moderate to severe HIE treated with TH.

Interventions

Continuous EKG data from 2 hours prior to rewarming through 2 hours after completion of rewarming (up to 10 hours) were analyzed.

Measurements and Main Results

Median beat-to-beat interval (RRi) and measures of HRV were quantified including RRi standard deviation (SD), low (LF) and high (HF) frequency relative spectral power, detrended fluctuation analysis short- and long- α exponents (αS, αL) and root mean square short- and long- time scales (RMSS, RMSL). The relationships between HRV measures and esophageal/axillary temperatures were evaluated. HRV measures LF, αS, RMSS, and RMSL were negatively associated, while αL was positively associated, with temperature (P<0.01). These findings signify an overall decrease in HRV as temperature increased towards normothermia.

Conclusions

Measures of HRV are temperature dependent in the range of TH to normothermia. Core body temperature needs to be considered when evaluating HRV metrics as potential physiological biomarkers of illness severity in HIE infants undergoing TH.

Keywords: neonatal intensive care unit, heart rate variability, therapeutic hypothermia, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, temperature

Introduction

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) resulting from acute perinatal asphyxia is a significant cause of neurodevelopmental disability in term infants.(1, 2) Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) has been demonstrated to improve outcomes and has become the current standard of care.(3, 4) 3 However, nearly half of infants with moderate to severe HIE continue to suffer death or disability despite treatment with cooling.(3) Current and future investigations will focus on identifying adjuvant neuroprotective therapies to further improve outcomes in newborns with HIE. However, monitoring adequate therapeutic response acutely and identifying HIE infants in need of alternate treatments remains clinically challenging. Clinicians need readily accessible real-time biomarkers of disease progression to better guide potential interventions and aid in therapeutic decisions.

The quantitative analysis of cardiac beat-to-beat intervals (RRi) has been increasingly recognized as a convenient means for bedside physiological assessment of the critically ill infant. A growing body of research supports the use of quantitative measures of RRi variability (i.e. heart rate variability (HRV)) as a noninvasive tool for early detection of autonomic dysfunction and clinical deterioration in infants.(5-8) More recently, we and others have reported that HRV metrics may be used to stratify HIE newborns by severity (9, 10) and identify infants who are at greatest risk for death or severe MRI brain injury (11) or neurodevelopmental impairment.(12, 13) Thus, the use of HRV holds promise as a physiological biomarker to guide management of newborns with HIE.

While standards have been proposed for evaluating HRV in adult patients(14), recent methodological advances have allowed for characterization of HRV via alternative methods (15). We previously described novel methods to quantify HRV in newborns via advanced signals processing approaches including frequency domain-based spectral analysis (SA) and time domain-based detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA), a method stemming from the concept of statistical physics. (16, 17) These methods can account for non-stationarity common in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit setting and have been adapted to the unique physiology observed in the newborn. These methods can offer additional measures to characterize features of HRV beyond traditional statistics such as standard deviation of the RRi (SDNN). SA relative low frequency (LF) power quantifies predominantly the sympathetic tone, while the high frequency (HF) power band quantifies the parasympathetic (vagal) tone of the ANS.(18, 19) The DFA root mean square (RMS) fluctuation and α exponents quantify the variability and autocorrelations in the RRi respectively, in short (s) and long (L) time scales. αS, RMS S and RMS L reflect the sympathetic tone of the ANS, while αL characterizes slow (2.5 minutes) changes in heart rate. (17, 20) These metrics can be quantified in real-time to allow for automated evaluation of continuous EKG data, a requisite feature for a viable bedside tool.

However, before advancing HRV into more widespread validation and ultimately bedside use, potential clinical confounders that may affect HRV in the setting of hypothermia must be better understood. While sinus bradycardia during cooling and mild hypotension due to vasodilation during rewarming are known cardiovascular side effects of therapeutic hypothermia, (21-23) the effect of TH on specific HRV metrics has not been fully characterized. This is important as animal data (24, 25) and studies in adults (26-29) and preterm infants (30) suggest an association between HRV measures and temperature. On the basis of these prior studies, it was hypothesized that HRV metrics would be significantly associated with changes in core body temperature during rewarming in newborns after TH.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Newborns enrolled in this study were part of an ongoing prospective study evaluating physiological and biochemical biomarkers of brain injury in babies with HIE. Infants were treated with whole-body hypothermia according to the NICHD Neonatal Research Network protocol, with inclusion criteria according to established NICHD criteria (i.e. infants were greater than 36 weeks gestational age, greater than 1800 grams at birth, demonstrated metabolic acidosis and/or low Apgar scores, and exhibited signs of moderate to severe clinical encephalopathy).(3) Infants were passively cooled during transport and then initiated on active cooling immediately upon arrival to the NICU. Infants were maintained at a target temperature of 33.5 °C using the Blanketrol® II cooling unit (Cincinnati Sub-Zero, Cincinnati OH) for 72 hours, followed by rewarming by 0.5 °C per hour over 6 hours to normothermia (36.5 °C). The study was approved by the Children's National Health System Institutional Review Board. Informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Authorization were obtained from the parent of the participant.

Data Collection

Demographic and clinical data were collected from birth hospital and NICU medical records. Continuous recordings of EKG from the NICU bedside cardiorespiratory monitor (Philips IntelliVue MP70, MA, USA) were collected prospectively in a time-locked manner at a rate of 500 Hz and up-sampled to 1 kHz using custom software developed in LabView (National Instruments, TX, USA). For newborns not enrolled within 24 hours of life, EKG data were collected if available from an institutional Research Data Export (RDE) archive (IntelliVue Information Center, Philips Healthcare, MA, USA). EKG data from 2 hours prior to rewarming through 2 hours after completion of rewarming (a total of 10 hours) were analyzed. Serial hourly measurements of core body temperature from the esophageal temperature probe (Steri-probe, Cincinnati Sub-Zero, Cincinnati OH) were recorded. If esophageal temperatures were not documented, then axillary temperatures were used. If more than one temperature was recorded for a given hour, then the values were averaged.

EKG Signal Pre-Processing

Signal processing was done using MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc., MA, USA) as previously described.(12, 16) Briefly, after the data were bandpass filtered between 0.5–70Hz, and semi-automated artifact rejection applied, the R-wave was identified using adaptive Hilbert transform approach (31, 32). For spectral analysis the RRi was converted into evenly sampled data using cubic-spline interpolation at a sample rate of 4 Hz. The data were divided into 10-minute windows for calculation of HRV metrics.

HRV metrics

HRV metrics were calculated within each 10-minute window according to established methods using traditional statistics and advanced signals processing approaches in the frequency and time domains. The median value of the HRV metrics calculated within a given hour was used for statistical analyses.

Traditional Statistics

The median and standard deviation of the RRi (SDNN) were calculated within each 10-minute window. The median RRi is a quantitative measure of heart rate whereas the SDNN is a measure of HRV.

Frequency Domain - Spectral Analysis (SA)

In each 10-minute window, the power spectrum was estimated via previously described methods.(12, 16) The relative low frequency (LF) and high frequency (HF) power were analyzed as measures of autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation of HRV.(18, 19) The LF power was calculated as the sum of power in the frequency bands covering 0.05–0.25 Hz, (30, 33-35) while HF power was calculated as the sum of power in the frequency bands covering 0.3–1 Hz.(30, 33-36). Both LF and HF power were divided by the total power (sum of power in the frequency bands covering 0.05– 2Hz) to calculate the relative LF and HF power. These frequency bands were selected to quantify the respiratory oscillations in the heart rate of neonates as previously described (30, 34, 35).

Time Domain - Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA)

DFA metrics were also calculated in each 10-minute window as previously described.(17) The α exponent quantifies the autocorrelations in the RRi for different time scales (short (αS): 15-30 beats and long (αL): >40 beats).(20) The root mean square fluctuation in short (RMS S) and long (RMS L) time scales were also calculated. The RMS fluctuation quantifies the variability in the RRi in the corresponding time scales.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included means (standard deviations) and medians (ranges) for continuous parametric and non-parametric variables, respectively, as well as counts (percentages) for categorical data. Since the dependent (HRV metrics) and independent variables (temperatures) included repeated measures for each patient, random effect regression models were used to take into account the intra-subject covariance. HRV data were log transformed to satisfy the normality assumption. Secondary models were also developed to adjust for patient characteristics including birth weight, gestational age, gender, encephalopathy grade (3, 37) at presentation, presenting pH, and the presence of hypotension (defined as the need for vasopressor medications during TH). Sensitivity analyses were also performed considering only esophageal temperatures and stratifying by grade of encephalopathy to evaluate the consistency of results. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 51 patients with moderate to severe HIE were enrolled. Data were unavailable for 7 patients because they either died after withdrawal of care prior to completion of TH (n=6) or EKG data were not able to be retrieved from the RDE archive (n=1). Thus, EKG and temperature data from 44 newborns with HIE were analyzed. The majority (n=34) were prospectively monitored, while ten patients' EKG data were retrieved from the RDE archive. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Patients with unavailable data were similar to the study population with regard to baseline and clinical characteristics (p>0.05). The median (interquartile range) duration of EKG recording per subject was 8 (2) hours, providing 343 observations for analyses. Reduced models with only esophageal temperatures included 190 observations.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data of the Study Population (n=44).

| Variable | Summary Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Birthweight (mean ± SD Kilograms) | 3.3 ± 0.8 |

| Gestational Age (mean ± SD weeks) | 38.9 ± 1.4 |

| Gender (n, % male) | 23 (52) |

| Presenting pH* | 6.9 (0.3) |

| Presenting Base Deficit*,a | 19 (8) |

| Encephalopathy Grade | |

| • Moderate (n, %) | 35 (80) |

| • Severe (n, %) | 9 (20) |

| Apgar Score* | |

| • 1 minute | 1 (1) |

| • 5 minute | 3 (3) |

| • 10 minute b | 5 (4) |

| EEG seizures during hypothermia (n, %) | 12 (27) |

| Hypotension during hypothermia (n, %) | 25 (57) |

| • Dopamine (n, %) c | 25 (100) |

| • Epinephrine (n%) c | 7 (28) |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) except where indicated.

Data available for

31/44 and

37/44 infants.

% refers to percentage of hypotension.

Traditional Statistics

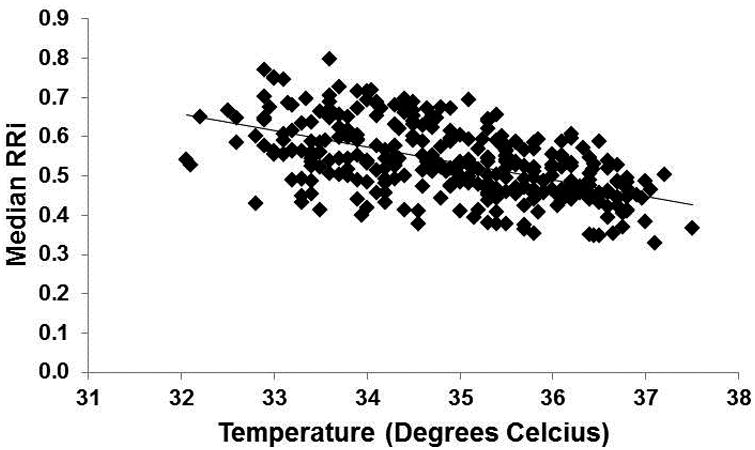

As expected, heart rate increased (median RRi decreased) with increasing temperature (Figure 1). This relationship remained significant after adjusting for covariates (Table 2). The SD of the RRi was not significantly associated with temperature (p>0.05).

Figure 1.

Relationship between median RRi and body temperature (beta= -0.064, standard error= 0.005, unadjusted p<0.001).

Table 2. Regression Model Results.

| Esophageal/Axillary Temperatureb (n=343 observations) | Esophageal Temperatureb (n=190 observations) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate Metrica | t-value | P-value | Adjustedc t-value | Adjustedc p-value | Significant Covariates | t-value | p-value | Adjustedc t-value | Adjustedc p-value | Significant Covariates |

| Median RRi | -13.57 | <0.001 | -14.02 | <0.001 | pH | -9.04 | <0.001 | -8.95 | <0.001 | |

| SDNN | -0.73 | 0.464 | -0.77 | 0.440 | -1.21 | 0.2274 | -1.26 | 0.2105 | Gender | |

| LF Power | -3.29 | 0.001 | -3.35 | 0.001 | Enceph | -2.32 | 0.022 | -2.28 | 0.024 | Enceph |

| HF Power | 0.03 | 0.978 | 0.07 | 0.945 | -0.47 | 0.6379 | -0.72 | 0.4748 | Enceph | |

| DFA αS | -3.28 | 0.001 | -3.31 | 0.001 | Enceph | -1.35 | 0.1803 | -1.23 | 0.2203 | Enceph |

| DFA αL | 4.34 | <0.001 | 4.30 | <0.001 | Enceph | 3.42 | <0.001 | 3.38 | <0.001 | |

| DFA RMSS | -10.50 | <0.001 | -10.38 | <0.001 | Enceph, pH | -4.66 | <0.001 | -4.81 | <0.001 | |

| DFA RMSS | -8.33 | <0.001 | -8.23 | <0.001 | Enceph | -4.41 | <0.001 | -4.39 | <0.001 | Enceph |

RRi= cardiac beat-to-beat intervals; SDNN= standard deviation of RRi; LF= low frequency; HF= high frequency; DFA- detrended fluctuation analysis; α= alpha exponent; S= short time scales; L= long time scales; RMS= root mean square.

Dependent variable;

Independent variable;

Adjusted for birth weight, gestational age, gender, encephalopathy grade at presentation (Enceph), presenting pH, hypotension (need for inotropes)

Frequency (SA) and Time (DFA) Domain HRV Metrics

A summary of the regression models is presented in Table 2. Temperature was negatively associated with LF Power, αS, RMSS and RMSL, and these relationships remained significant after controlling for covariates (p<0.01). Encephalopathy grade was also negatively associated with these HRV metrics (signifying reduced HRV in patients with more severe encephalopathy) across models (p<0.01). Conversely, αL was positively associated with temperature (p<0.001) and encephalopathy grade (p=0.014). HF power was not associated with temperature (p>0.05).

Secondary Sensitivity Analyses

Relationships between HRV metrics and temperature remained consistent when considering only esophageal temperatures, except for αS which remained negatively associated with temperature although this relationship did not reach statistical significance in the reduced models (Table 2). Although the interaction between encephalopathy grade and temperature was not significant, we proceeded with analyses after stratifying by encephalopathy grade to assess the impact of this important confounder. Infants with moderate encephalopathy showed similar relationships between HRV and temperature as the overall cohort. Although only 8 patients had severe encephalopathy, significant associations between median RRi (estimate -0.045, p=0.009) and RMSS (estimate -0.148, p=0.007) were observed in these patients.

Discussion

This is the first clinical study to evaluate the relationship between HRV and temperature in newborns undergoing TH. Across the range of temperatures observed during the rewarming period, we demonstrate a significant relationship between several HRV metrics and temperature. Specifically, we observed an overall reduction in HRV as temperature increased towards normothermia. This has important implications as the use of HRV as a viable biomarker of disease severity has been recently proposed in several studies.(11-13) In particular, we recently demonstrated that a key period during the temporal evolution of HRV in newborns with HIE coincided with the rewarming period.(12) The current study underscores the importance of accounting for temperature in future analyses, to be sure that this observation reflects the disease evolution of HIE rather than changes in core temperature over the rewarming process.

While prior studies have consistently shown reduced HRV in HIE newborns with poor outcomes, (9-13) the mechanisms for this observation have not been fully elucidated. Decreased HRV may be attributable to direct subcortical or brainstem injury leading to autonomic dysfunction,(38) the effects of asphyxia on the cardiovascular system,(22) the presence of seizures, (39-41) or likely a combination of these and other factors. As studies move forward towards more large-scale validation of HRV as a bedside biomarker in HIE, understanding potential confounding factors that can influence HRV under different clinical circumstances is crucial. Our study suggests that temperature variation in the moderate hypothermia range is a factor influencing HRV that needs to be addressed in future studies.

Several studies in adults have suggested a relationship between HRV and both ambient(27) and core body temperature.(26, 28, 29) Studies in healthy preterm and term infants have focused on elevations in ambient temperature and its effect on HRV as a possible etiology for sudden infant death syndrome.(30, 42) These prior studies have highlighted the complexity of the association between temperature and HRV, with one study describing non-linear relationships and inverse patterns at temperature extremes.(26) Few studies have investigated temperature effect on HRV in the setting of therapeutic hypothermia. Tiainen and colleagues reported increased HRV in adults undergoing hypothermia after cardiac arrest.(28) Only one small study involving 2 newborns undergoing TH for HIE likewise reported a negative association between LF Power and temperature.(33) These investigators also found a negative association between HF Power and temperature as well as a positive association between LF/HF ratio and temperature. We did not evaluate LF/HF ratio as recent reports have questioned whether this measure accurately reflects the sympatho-vagal balance as originally proposed.(43) That we did not find a significant relationship between temperature and HF Power may be attributable to the observation that HF Power is less dynamic and appears to have less overall variability during this time period in newborns with HIE.(12) This may also explain why no association was observed between RRi SD and temperature, as RRi SD provides an overall gross measure of variability rather than evaluating the contributions of specific inputs (e.g. sympathetic or parasympathetic) that may have differential relationships with temperature. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date evaluating the relationship between HRV metrics and temperature in newborns undergoing cooling.

Our findings of increased HRV at lower temperatures are consistent with prior animal (25) and human studies(28, 29, 33) evaluating HRV in the temperature range of moderate therapeutic hypothermia. The temperature-dependency of HRV may be explained via several possible mechanisms. As HRV has been described to be inversely related to heart rate,(44) the change in HRV may be attributable to the relationship between heart rate (median RRi) and temperature alone. Alternatively, there may be direct effects of hypothermia on the myocardium that preserve HRV.(25, 28) Finally, it is also possible that the reduction in HRV over the rewarming process reflects withdrawal of the therapeutic effect of hypothermia and may signify a potential benefit for continued hypothermia in some patients. Irrespective of the mechanisms by which body temperature interacts with HRV, our study supports that this relationship exists and may represent a clinically relevant covariate when considering HRV as a physiological biomarker in neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Incorporation of patient temperature may be important as future HRV monitoring paradigms are developed for bedside application.

Several limitations of our study must be recognized. Not all patients contributed 10 hours of continuous data as some recordings were stopped due to clinical reasons. RDE retrieved data were incomplete for the time period of interest, or segments were excluded due to artifact. Although this may be a potential source of bias, the large number of observations provided by a continuous dataset mitigated any impact these missing data may have had on sample size for analyses. Although artifact in the EKG recordings could also impact results, our analytical approach incorporated a robust automated artifact rejection method.(16) Finally, we collected temperature data from the medical record. This allowed for limited resolution (hourly) and the need to consider both esophageal and axillary temperatures for more complete and unbiased data. While a recent study suggested that axillary temperatures have limited correlation with core temperature in babies undergoing hypothermia (45), axillary temperature remains the mainstay of temperature monitoring in newborns (46, 47) and has been reasonably correlated to core temperature in other studies (48, 49). Our results were similar when considering only available esophageal temperatures. Consistency of findings across these two analyses provides confidence in the relationships observed between temperature and HRV. Likewise, our sample size limited our ability to clearly elucidate the relationship between HRV metrics and temperature in infants with severe encephalopathy. Future studies are needed (and planned) with higher resolution core temperature data to further evaluate the relationship between temperature and HRV metrics in babies with moderate to severe HIE.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nickie N. Andescavage, M.D. and Rhiya Dave, B.A. for their assistance with data collection for this study.

Statement of financial support: This work was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National (UL1TR000075, 1KL2RR031987-01) and the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Consortium (NIH P30HD040677).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Dilenge ME, Majnemer A, Shevell MI. Long-term developmental outcome of asphyxiated term neonates. Journal of child neurology. 2001;16(11):781–792. doi: 10.1177/08830738010160110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankaran S, Woldt E, Koepke T, et al. Acute neonatal morbidity and long-term central nervous system sequelae of perinatal asphyxia in term infants. Early human development. 1991;25(2):135–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(91)90191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353(15):1574–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins RD, Raju T, Edwards AD, et al. Hypothermia and other treatment options for neonatal encephalopathy: an executive summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD workshop. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;159(5):851–858 e851. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairchild KD, O'Shea TM. Heart rate characteristics: physiomarkers for detection of late-onset neonatal sepsis. Clinics in perinatology. 2010;37(3):581–598. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone ML, Tatum PM, Weitkamp JH, et al. Abnormal heart rate characteristics before clinical diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2013 doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairchild KD, Schelonka RL, Kaufman DA, et al. Septicemia mortality reduction in neonates in a heart rate characteristics monitoring trial. Pediatric research. 2013 doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairchild KD, Sinkin RA, Davalian F, et al. Abnormal heart rate characteristics are associated with abnormal neuroimaging and outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2014;34(5):375–379. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matic V, Cherian PJ, Widjaja D, et al. Heart rate variability in newborns with hypoxic brain injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;789:43–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7411-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aliefendioglu D, Dogru T, Albayrak M, et al. Heart rate variability in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(11):1468–1472. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vergales BD, Zanelli SA, Matsumoto JA, et al. Depressed heart rate variability is associated with abnormal EEG, MRI, and death in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. American journal of perinatology. 2014;31(10):855–862. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massaro AN, Govindan RB, Al-Shargabi T, et al. Heart rate variability in encephalopathic newborns during and after therapeutic hypothermia. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2014 doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulding RM, Stevenson NJ, Murray DM, et al. Heart rate variability in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: correlation with EEG grade and 2-y neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatric research. 2015;77(5):681–687. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93(5):1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sassi R, Cerutti S, Lombardi F, et al. Advances in heart rate variability signal analysis: joint position statement by the e-Cardiology ESC Working Group and the European Heart Rhythm Association co-endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2015;17(9):1341–1353. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govindan RB, Massaro AN, Niforatos N, et al. Mitigating the effect of non-stationarity in spectral analysis-an application to neonate heart rate analysis. Computers in biology and medicine. 2013;43(12):2001–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindan RB, Massaro AN, Al-Shargabi T, et al. Detrended fluctuation analysis of non-stationary cardiac beat-to-beat interval of sick infants. Europhysics Lett. 2014;108:40005–p40001-p40006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccirillo G, Magri D, Ogawa M, et al. Autonomic nervous system activity measured directly and QT interval variability in normal and pacing-induced tachycardia heart failure dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(9):840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccirillo G, Ogawa M, Song J, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability and autonomic nervous system activity measured directly in healthy dogs and dogs with tachycardia-induced heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(4):546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunde A, Havlin S, Kantelhardt JW, et al. Correlated and uncorrelated regions in heart-rate fluctuations during sleep. Physical review letters. 2000;85(17):3736–3739. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD003311. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thoresen M, Whitelaw A. Cardiovascular changes during mild therapeutic hypothermia and rewarming in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):92–99. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavallaro G, Filippi L, Raffaeli G, et al. Heart Rate and Arterial Pressure Changes during Whole-Body Deep Hypothermia. ISRN pediatrics. 2013;2013:140213. doi: 10.1155/2013/140213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang YT, Wann SR, Wu PL, et al. Influence of age on heart rate variability during therapeutic hypothermia in a rat model. Resuscitation. 2011;82(10):1350–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer SF, Lambertz M, Langhorst P, et al. Interbeat interval variability in isolated working rat hearts at various dynamic conditions and temperatures. Research in experimental medicine Zeitschrift fur die gesamte experimentelle Medizin einschliesslich experimenteller Chirurgie. 1999;199(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s004330050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mowery NT, Morris JA, Jr, Jenkins JM, et al. Core temperature variation is associated with heart rate variability independent of cardiac index: a study of 278 trauma patients. Journal of critical care. 2011;26(5):534 e539–534 e517. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Deng F, Liu Y, et al. Temperature, traffic-related air pollution, and heart rate variability in a panel of healthy adults. Environmental research. 2013;120:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiainen M, Parikka HJ, Makijarvi MA, et al. Arrhythmias and heart rate variability during and after therapeutic hypothermia for cardiac arrest. Critical care medicine. 2009;37(2):403–409. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819572c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKenzie MA, Aengevaeren WR, Hermus AR, et al. Electrocardiographic changes during steady mild hypothermia and normothermia in patients with poikilothermia. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;82(1):39–45. doi: 10.1042/cs0820039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephan-Blanchard E, Chardon K, Leke A, et al. Heart rate variability in sleeping preterm neonates exposed to cool and warm thermal conditions. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e68211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Govindan RB, Vairavan S, Ulusar UD, et al. A novel approach to track fetal movement using multi-sensor magnetocardiographic recordings. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2011;39(3):964–972. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulusar UD, Govindan RB, Wilson JD, et al. Adaptive rule based fetal QRS complex detection using Hilbert transform. Conference proceedings : Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference. 2009;2009:4666–4669. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasky RE, Parikh NA, Williams AL, et al. Changes in the PQRST intervals and heart rate variability associated with rewarming in two newborns undergoing hypothermia therapy. Neonatology. 2009;96(2):93–95. doi: 10.1159/000205385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortrat JO. Inaccurate normal values of heart rate variability spectral analysis in newborn infants. The American journal of cardiology. 2002;90(3):346. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giddens DP, Kitney RI. Neonatal heart rate variability and its relation to respiration. Journal of theoretical biology. 1985;113(4):759–780. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(85)80192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andriessen P, Oetomo SB, Peters C, et al. Baroreceptor reflex sensitivity in human neonates: the effect of postmenstrual age. The Journal of physiology. 2005;568(Pt 1):333–341. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Archives of neurology. 1976;33(10):696–705. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100030012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George S, Gunn AJ, Westgate JA, et al. Fetal heart rate variability and brain stem injury after asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2004;287(4):R925–933. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00263.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assaf N, Weller B, Deutsh-Castel T, et al. The relationship between heart rate variability and epileptiform activity among children--a controlled study. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2008;25(5):317–320. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e318182ed2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malarvili MB, Mesbah M. Newborn seizure detection based on heart rate variability. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56(11):2594–2603. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2026908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malarvili MB, Mesbah M. Combining newborn EEG and HRV information for automatic seizure detection. Conference proceedings : Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference. 2008;2008:4756–4759. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franco P, Szliwowski H, Dramaix M, et al. Influence of ambient temperature on sleep characteristics and autonomic nervous control in healthy infants. Sleep. 2000;23(3):401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Billman GE. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol. 2013;4:26. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT, Jr, et al. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. The American journal of cardiology. 1987;59(4):256–262. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landry MA, Doyle LW, Lee K, et al. Axillary temperature measurement during hypothermia treatment for neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2013;98(1):F54–58. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith J, Alcock G, Usher K. Temperature measurement in the preterm and term neonate: a review of the literature. Neonatal network : NN. 2013;32(1):16–25. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.32.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hospital stay for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):405–409. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedrichs J, Staffileno BA, Fogg L, et al. Axillary temperatures in full-term newborn infants: using evidence to guide safe and effective practice. Advances in neonatal care : official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses. 2013;13(5):361–368. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3182a14f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nonose Y, Sato Y, Kabayama H, et al. Accuracy of recorded body temperature of critically ill patients related to measurement site: a prospective observational study. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2012;40(5):820–824. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]