Significance

Wave propagation through a 1D disordered potential is always confined spatially due to the constructive interference in the backward direction. This “Anderson localization” behavior applies to all previously known 1D disordered systems in nature. Here, we show that wave propagating in 2D pseudospin-1 systems with 1D disorder has unique localization behaviors. In all conventional materials, stronger disorder always induces stronger localization. However, the localization in pseudospin-1 systems actually becomes weaker after the randomness increases beyond a critical value and a sharp transition separates the localization behavior into two regimes with different localization characteristics. Pseudospin-1 systems have been achieved in artificial crystals such as metamaterials and ultracold atom systems, which would be interesting platforms to observe the anomalous localization behaviors.

Keywords: localization, pseudospin, disorder, evanescent waves, photonic crystals

Abstract

We discovered unique Anderson localization behaviors of pseudospin systems in a 1D disordered potential. For a pseudospin-1 system, due to the absence of backscattering under normal incidence and the presence of a conical band structure, the wave localization behaviors are entirely different from those of conventional disordered systems. We show that there exists a critical strength of random potential (), which is equal to the incident energy (), below which the localization length decreases with the random strength for a fixed incident angle . But the localization length drops abruptly to a minimum at and rises immediately afterward. The incident angle dependence of the localization length has different asymptotic behaviors in the two regions of random strength, with when and when . The existence of a sharp transition at is due to the emergence of evanescent waves in the systems when . Such localization behavior is unique to pseudospin-1 systems. For pseudospin-1/2 systems, there is also a minimum localization length as randomness increases, but the transition from decreasing to increasing localization length at the minimum is smooth rather than abrupt. In both decreasing and increasing regions, the dependence of the localization length has the same asymptotic behavior .

Anderson localization is one of the most fundamental and universal phenomena in disordered systems. Anderson’s seminal work (1) has inspired intensive studies on the effect of randomness in a vast variety of electronic and classical wave systems (2–10). Meanwhile, the rapid progress in experimental techniques enables us to reach an unprecedented level of manipulating artificial materials such as ultracold atomic gases (11) and nano/microdielectric structures (12), making it possible to create new materials with unusual transport properties (11–14). The interplay between disorder and new artificial materials continues to generate many amazing phenomena, such as the suppression of Anderson localization in metamaterials (15–17), supercollimation of electron beams in 1D disorder potentials (18), and delocalization of relativistic Dirac particles in 1D disordered systems (19).

Among these new materials, pseudospin-1/2 materials are of particular interest due to their conical band structure and the chiral nature of the underlying quasiparticle states. A prototypical example of such materials is graphene (13, 14). The low-energy excitations in graphene behave like massless Dirac particles and the orbital wave function can be represented by a two-component spinor, with each component corresponding to the amplitude of the electron wave function on one of the trigonal sublattices of graphene. We emphasize that the “pseudospin-1/2” character in graphene refers to the spatial degree of freedom and has nothing to do with the intrinsic spin of electrons. The Dirac cone and the associated pseudospin-1/2 characteristic of quasiparticles can also be found in a wide range of quantum and classical wave systems, such as topological insulators (20, 21) and the photonic and phononic counterparts of graphene (22–24). Recently, pseudospin-1 systems have also attracted much attention (23–38). Different from the Dirac cones in graphene, a Dirac-like cone is found in pseudospin-1 systems where two cones meet and intersect with an additional flat band at a Dirac-like point. For example, certain photonic crystals (PCs) can exhibit such conical dispersions at the Brillouin zone center due to the accidental degeneracy of monopole and dipole excitations (23–27), which combines to give three degrees of freedom. The physics near the Dirac-like point can be described by an effective spin-orbit Hamiltonian with pseudospin and their wave functions are represented by a three-component spinor. Such systems are called “pseudospin-1 materials” (27). These systems have also been theoretically predicted (28–32) and experimentally realized by manipulating ultracold atoms in an optical lattice (33) or arranging an array of optical waveguides in a Lieb lattice (34–37). As an analogy with the gate voltage in graphene and other charged Dirac fermion systems, the potentials in pseudospin-1 systems can be shifted up and down by a simple change of length scale in PCs (27) or an appropriate holographic mask in ultracold atom systems (28–32).

Whereas these pseudospin Hamiltonians share the common feature of conical dispersions near a singular point, different pseudospin numbers (1 vs. 1/2) give rise to distinct physical behaviors. For example, carriers in pseudospin-1/2 systems encircling the Dirac point pick up a Berry phase of whereas those in pseudospin-1 systems pick up a Berry phase of 0 (14, 27), meaning that the topological characteristics of the wave functions in momentum space depend on the pseudospin numbers and the localization behaviors may be different. In addition, in the presence of a 2D potential barrier, scattering of low-energy carriers in pseudospin-1/2 systems gives zero backscattering amplitude, whereas the scattering is isotropic for pseudospin-1 systems (38). The scattering behavior in the presence of a 1D potential barrier is also different. For example, the so-called “super-Klein tunneling” (perfect transmission for all incident angles when the incident energy equals half of the barrier) can exist only in pseudospin-1 systems (27–32). In 1D disordered graphene superlattices, localization behaviors such as angle-dependent electron transmission (39, 40) and directional filtering due to strong angle-dependent localization length (41) have been predicted. We present here some surprising, counterintuitive transport phenomena for pseudospin-1 systems in 1D disordered potentials (Fig. 1). We also show results of pseudospin-1/2 systems for comparison.

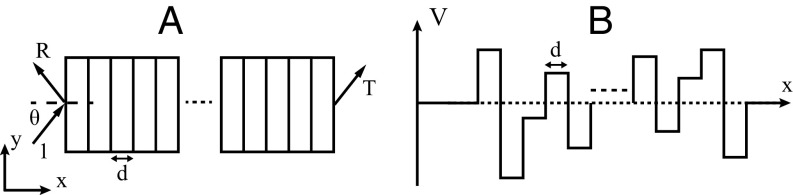

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of 1D disordered systems. (A) Top view of the structure. Each layer has the same thickness , but feels a randomized potential. (B) One possible realization of random potentials. The potentials are uniformly distributed in the range .

The disorder-induced localization behavior in pseudospin-1 systems under 1D disordered potentials is entirely different from that in any conventional disordered systems, in which all states become localized in 1D random potentials due to the constructive interference of two counterpropagating waves in the backward direction (2–5). However, for pseudospin-1 systems, a disordered 1D potential gives rise to a random phase only in the spatial wave function and does not produce any backward scatterings for waves propagating in the normal direction. Such behavior was first discovered in pseudospin-1/2 systems (14, 19, 42, 43). In the case of pseudospin-1 electromagnetic (EM) waves (27), the absence of backscattering can be interpreted as the impedance match between any two adjacent layers in such systems. Thus, Anderson localization occurs only for obliquely incident waves. It is interesting to point out that for conventional random layered media the impedance matching condition can also lead to a diverging localization length for p waves at some incident angle known as the stochastic Brewster effect (44, 45).

Furthermore, due to the existence of a Dirac-like point, the introduction of a disorder potential makes it possible to have evanescent waves occurring in the system when the potential at a certain layer is close to the incident energy. The presence of evanescent waves also makes the transport of waves different from that in conventional disordered systems. Here we show both analytically and numerically that, for pseudospin-1 systems, when the randomness is small so that no evanescent waves occur in any layer, the localization length decays with the incident angle according to at small . However, when the strength of the random potential reaches a critical value, which equals the incident energy of the wave, the localization length drops suddenly to a minimum and rises immediately afterward as evanescent waves emerge. In the latter case, the dependence of changes to a different behavior; i.e., . The sudden drop as well as the subsequently immediate rise of with increasing randomness and the change of the asymptotic behavior in the dependence are not seen in any conventional disordered systems, to the best of our knowledge (Fig. 2). In conventional disordered systems, always decreases with increasing randomness, consistent with our intuition that disorder should disrupt transmission. The existence of a critical randomness in pseudospin-1 systems suggests some kind of sharp transition between two localization phases. The physical origin of such a transition is the occurrence of evanescent waves in certain fluctuating layers with randomness that is beyond the critical randomness. Evanescent waves are known to produce a diffusive-like transport in an ordered graphene at the Dirac point (46, 47). We discover that evanescent waves can produce even more fascinating transport behaviors in disordered pseudospin-1 systems. For pseudospin-1/2 systems in 1D disordered potentials, our results find a smooth crossover in the localization length behavior, from a decreasing one at small randomness to an increasing one at large randomness, and an angular dependence of in both the localization length decreasing and increasing regimes. We show that the absence of the sharp transition in pseudospin-1/2 systems is due to the presence of additional interface scatterings, which produces a behavior even at small randomness. Thus, the -dependent localization length behavior does not change when the randomness is increased.

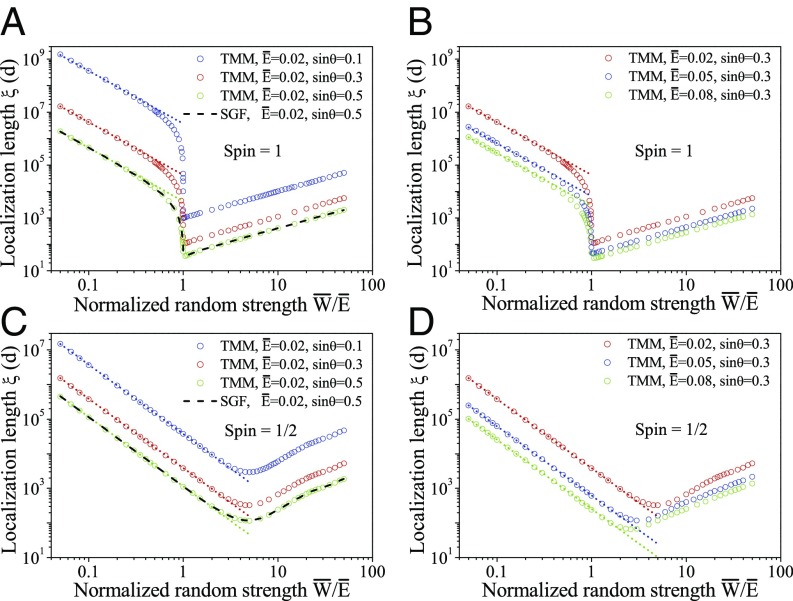

Fig. 2.

Localization length as a function of normalized random potential strength for different incident angles and energies in 1D disordered pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems calculated with the TMM. (A) Localization length for three different incident angles in pseudospin-1 systems. (B) Localization length for three different incident energies in pseudospin-1 systems. (C) Same as A, but for pseudospin-1/2 systems. (D) Same as B, but for pseudospin-1/2 systems. The black dashed lines in A and C show the results obtained by the surface Green function (SGF) method. The localization lengths for small are fitted by dotted lines, showing an asymptotic behavior . Both and are in units of .

Results and Discussion

Models and Numerical Results.

The systems under investigation are pseudospin-1 systems in 1D disordered potentials, which are in the form of random layers (or strips). Each layer has the same thickness , but feels a random potential with a strength , as shown in Fig. 1. Here, denotes the energy of the Dirac-like point of the background medium. A plane wave is incident on the layered structure at an incident angle from the background with the incident energy . For normal incidence (), the waves are delocalized, irrespective of the strength of randomness due to the absence of backscattering (27). Here we consider oblique incidence (), for which Anderson localization can occur. It has been shown previously that the wave equation of such systems can be described by a generalized 2D Dirac equation with a 1D random potential (27–32),

| [1] |

Here is a spinor function, is the wavevector operator with and , is the matrix representation of the spin-1 operator, is the group velocity, and I is the identity matrix in the pseudospin space. We note that Eq. 1 is valid for both matter waves (quantum particles) (28–32) and EM waves (27) as long as the dispersion of the system near some high-symmetry k points can be described by the pseudospin-1 model. For simplicity, Eq. 1 can be rewritten as

| [2] |

with and . The normalized random potential in the th layer is taken to be (), which is an independent random variable distributed uniformly in the range ( is the random strength of the normalized potential). We can calculate the transmission coefficient through a random stack of layers by the transfer-matrix method (TMM) (27). The localization length , or the inverse of the Lyapunov exponent , is obtained through the relation

| [3] |

where denotes ensemble averaging.

We first show the localization length as a function of the random strength . Results of averaging over 4,000 configurations with taken to be five times the localization length are shown in Fig. 2 A and B for different incident angles and energies, respectively. At small randomness, these results show that the localization length decreases with increasing randomness following a general form , similar to the behavior found in ordinary disordered media (3, 4). However, if is further increased, the localization length drops abruptly to a minimum at a critical , independent of incident angle and energy, and rises immediately afterward.

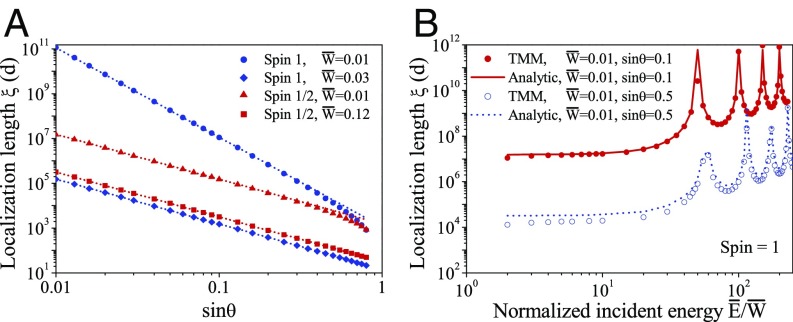

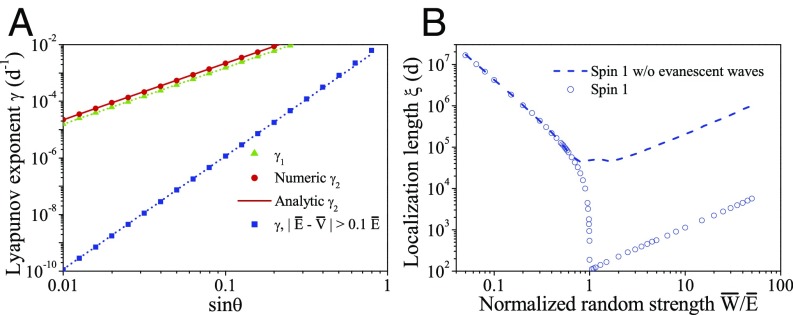

These results are rather intriguing. First, the cusp-like turnaround of localization behavior is not seen in any other disorder systems to our knowledge. For conventional disordered media, always decreases with increasing disorder. Second, the sudden change of localization behavior near the critical random strength indicates some kind of sharp transition between two different localization phases: and in the space. To further elaborate on this point, we examine the dependence of the localization length. The result of and small disorder () is shown by blue circles in Fig. 3A, where a log-log plot of vs. shows a straight line with a slope of for small incident angles , indicating a behavior. However, the slope changes to for a higher disorder () (blue diamonds), indicating a behavior. There is hence a change of localization behaviors from to in the two different regions of . We show analytically later that this transition occurs exactly at , and the physical origins of the above anomalous localization behaviors are the existence of the Dirac-like point and the occurrence of evanescent waves in some layers caused by a diverging scattering strength when .

Fig. 3.

Localization behaviors for disordered pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems. (A) Localization length as a function of incident angle for incident energy and two random strengths in 1D disordered pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems calculated using the TMM. The two random strengths are chosen from the respective decreasing and increasing regions in Fig. 2 A and C for pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems. The localization length of pseudospin-1 systems at small for () (blue circles) is fitted by a dotted line, showing . The other three cases are fitted by . (B) Comparison of the localization length calculated by using the TMM and analytical results shown in Eq. 14. Both and are in units of .

To see whether such anomalous localization behaviors also occur in pseudospin-1/2 systems, we studied numerically the localization length behaviors for such systems. The Hamiltonian of pseudospin-1/2 systems has the same form as Eq. 1 except that the wave function is a two-component spinor (14, 18) and the spin matrices become Pauli matrices. The results of the TMM are shown in Fig. 2 C and D. Compared with Fig. 2 A and B, for all incident angles and energies studied, the cusp-like sharp change in does not exist in pseudospin-1/2 systems. Instead, shows a smooth crossover from a decreasing behavior at small randomness to an increasing one at large randomness with a minimum around a few . Furthermore, the dependence of in both regions shows a behavior as shown in Fig. 3A. The difference in the dependence of in the two pseudospin systems is due to different scattering potentials for oblique waves. In the following, we present analytical derivations of the localization length for both systems.

Transformation from a Vector Wave Equation to a Scalar One.

For the layered structure, the wavevector component parallel to the interface (, where is the wavevector in the background) is conserved, with the same value in all layers. Thus, the wave functions for pseudospin-1 systems can be written as . Using the following matrix representation for the spin operator, ,

| [4] |

we rewrite Eq. 2 as

| [5] |

By eliminating and , we can convert Eq. 5 into a scalar wave equation for ,

| [6] |

Without loss of generality, we take the first interface of the -layer system as the origin, define a new dimensionless coordinate variable , and write and . Then, Eq. 6 can be reexpressed as

| [7] |

The above coordinate transformation changes a nonstandard wave equation, Eq. 6, to a standard one, Eq. 7, where the scattering potential due to the disordered potential is explicitly shown on the right-hand side of Eq. 7. In the case of normal incidence, i.e., , Eq. 7 describes wave propagation in a homogeneous medium and contains two general solutions . Thus, the accumulated random phase due to during the one-way transport is now absorbed in the new coordinate . For the layered structure where the potential is piecewise constant, the th interface in the coordinate, , is written as and for from the above coordinate transformation. It is important to point out that we have transformed a three-component vector wave equation for obliquely propagating waves, i.e., Eq. 1, into an equivalent scalar wave equation for normally propagating waves, and the oblique angle enters the wave equation in the scattering terms, i.e., Eq. 7. Such a transformation allows us to derive analytically certain asymptotic localization behaviors.

Similarly, we can use the Pauli matrices for the spin-1/2 operator in Eq. 1 to construct a scalar wave equation for pseudospin-1/2 systems. In the coordinate system, the wave equation has the form (Scalar Wave Equation)

| [8] |

where . Note that in comparison with pseudospin-1 systems, pseudospin-1/2 systems have additional interface scattering terms located at all interfaces.

The difference in the dependence of in the two systems shown in Fig. 3A, when is small, can be qualitatively understood from the scattering terms in Eqs. 7 and 8. For ordinary disordered media, it is well accepted that the localization length in 1D systems is on the order of the mean free path, which is inversely proportional to the square of the scattering strength (3). In the case of small , the dependence in the effective scattering potential of Eq. 7 gives rise to a (or ) behavior in the localization length, whereas the dependence in the interface scattering terms of Eq. 8 dominates and leads to a (or ) behavior. The sudden drop of localization length near for pseudospin-1 systems is due to the diverging scattering term in Eq. 7 when in some layers so that the waves become evanescent inside those layers. We show analytically that it is the existence of those evanescent waves that changes the dependence of from in the region to in the region . When goes beyond its critical value , the probability of having evanescent waves is reduced with increasing , and in the meantime, the scattering potentials in the propagating layers are weakened in general. As a result, increases with . However, such a sudden drop of is smeared out by the interface scattering terms in Eq. 8 so that a smooth change of localization behaviors is found for pseudospin-1/2 systems.

Lyapunov Exponent Obtained by the SGF Method.

Because Eqs. 7 and 8 are already in the form of scalar wave equations for normal-incident propagating waves, we can now solve the wave localization problem of pseudospin systems using the SGF method, which gives the following expression for the transmission coefficient of a normal-incident plane wave propagating through an -layered random system (48):

| [9] |

where

| [10] |

Here denotes the reflection amplitude of a plane wave incident from the th layer on the ( − 1)th layer, is the phase accumulation between the th and th interfaces of the sample, and is the determinant of an + 1 by + 1 matrix with the following elements:

| [11] |

The expressions for and are shown in Phase Accumulation and Reflection Amplitudes for both pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems. From Eqs. 9 and 10, we obtain the expression for Lyapunov exponent in Eq. 3 as

| [12] |

with and . We first numerically calculate the localization length by using Eq. 12 as a function of for a fixed incident angle and energy. The results are shown as black dashed lines in Fig. 2 A and C for pseudospin-1 and -1/2 systems, respectively. They are in excellent agreement with those obtained from the TMM.

Asymptotic -Dependent Localization Length Behavior in Region .

In the following, using Eq. 12, we show analytically that localization length follows the asymptotic behavior in the region of . In this case, the reflection amplitudes in pseudospin-1 systems can be approximated as , as long as . In this limit, as shown in Lyapunov Exponent in the Region of , the Lyapunov exponent can be written as

| [13] |

where and are coefficients corresponding to and , respectively. Note that in Eq. 13 is proportional to for the region . In the case of , we can further take a small expansion for and . It can be shown that and then reduce to simple forms, and . Thus, Eq. 13 gives the following expression for in the limit :

| [14] |

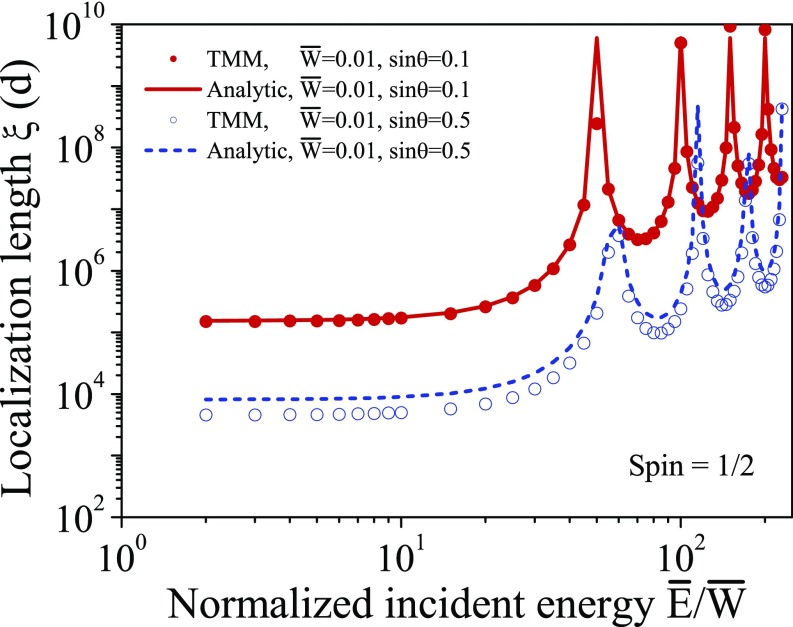

We also numerically calculated the localization length in this limit. The results are shown in Fig. 3B by the symbols. We find excellent agreement between the analytical and numerical results. We note that vanishes at certain energies that satisfy the on-average Fabry–Perot resonance condition (). Such Fabry–Perot resonance-induced anomalies were also observed in conventional 1D disordered materials (49–51). Thus, tends to diverge at these energies. The finite values of at these resonances are due to high-order corrections.

For pseudospin-1/2 systems, the asymptotic behavior of in the limit of small and can be obtained using a similar approach (Lyapunov Exponent in the Region of ,) and has the expression

| [15] |

The validity of Eq. 15 is also confirmed numerically (Fig. S1). From Eqs. 14 and 15, we can see that in both pseudospin systems the localization length decreases as , showing exactly the same behaviors in Fig. 2. More importantly, our analytical results prove that the pseudospin number indeed makes a profound difference on the localization behaviors, leading to a localization length behavior for small , where is the pseudospin number.

Fig. S1.

Comparison of the localization length calculated by using the TMM and analytical results shown in Eq. 15. Both and are in units of .

Asymptotic -Dependent Localization Length Behavior in Region .

In this case, there are strong scatterings for those layers with the potentials close to the incident energy due to the existence of singularity at in the scattering potential in Eq. 7, and hence the approximations used above are not applicable. Although the calculation becomes rather tedious, we still manage to obtain an analytic form of for pseudospin-1 systems ( for Pseudospin-1 Systems in the Case ); that is,

| [16] |

To confirm the validity of Eq. 16, we numerically calculate as a function of the incident angle for and . The result is plotted by red circles in Fig. 4A, which agrees excellently with the analytic expression (red solid line) shown in Eq. 16. Because the Lyapunov exponent, , is an even function of , we can safely conclude from Eq. 16 that the region represents a different localization phase in which the -dependent localization length has an asymptotic behavior, , different from the behavior found in the region as shown in Eq. 13. Such a sudden change of -dependent localization behavior at is accompanied by the cusp-like change of localization length from a decreasing function of when to an increasing one when as shown in Fig. 2 A and B. We show in for Pseudospin-1 Systems in the Case that the origin of the factor in is the occurrence of the diverging scattering potentials in certain layers when so that the waves become evanescent inside these layers. In fact, the presence of evanescent waves in certain layers also leads to a dependence in . Due to the complexity of the matrix , an explicit analytic expression for is formidable. We numerically calculate and plot the result by green triangles in Fig. 4A, which has an excellent fit to a dotted line showing . If the presence of evanescent waves is the origin that turns a dependence of into a dependence, we should be able to recover the behavior found in region by purposely excluding evanescent waves in the random media. To confirm this point, we calculate the dependence of for a particular random distribution of potentials, , but with a condition so that no evanescent waves will occur at sufficiently small . The result is plotted by blue squares in Fig. 4A. It is clearly seen that the behavior is indeed recovered. In fact, the sudden drop of near shown in Fig. 2 A and B is also due to the presence of evanescent waves in some layers. To show this, we numerically calculate as a function of by excluding the evanescent waves. The result is plotted by a blue dashed line in Fig. 4B. In comparison with the result with evanescent waves included (blue circles), we can see that the sudden drop of near disappears.

Fig. 4.

Effect of evanescent waves on the localization behaviors in pseudospin-1 systems. (A) Comparison of the Lyapunov exponents as a function of incident angle with and without evanescent waves included in 1D disordered pseudospin-1 systems at and . In the case with evanescent waves, at small (green triangles) is fitted by a dotted line showing , and the numerical result of (red circles) agrees excellently with the analytic prediction in Eq. 16 (red solid line). For the random distribution of potentials , no evanescent waves occur at sufficiently small . in this case (blue squares) shows an excellent fit to a dotted line for small . (B) Comparison between the localization lengths with and without evanescent waves for pseudospin-1 systems with and . Both and are in units of .

However, for pseudospin-1/2 systems, propagating waves also contribute to a term due to the interface scattering terms in Eq. 8, which smears out the sudden drop of , as shown in Fig. 2 C and D, and leads to the same asymptotic dependence of for all s in Fig. 3A.

Conclusions

We discovered interesting anomalous localization behaviors in disordered pseudospin-1 systems, using the TMM as well as analytical solutions from the SGF method. In contrast to ordinary 1D random media where stronger randomness always induces stronger localization, pseudospin-1 systems have a critical random strength at which a cusp-like turnaround occurs in the localization length as a function of randomness. Additional randomness beyond this critical strength makes the wave less localized. Such a sudden change gives rise to two localization phases characterized by different asymptotic dependence of the localization length; i.e., when and when . Such anomalous behaviors arise from the existence of a Dirac-like point and the occurrence of the evanescent waves in the region . For pseudospin-1/2 systems, we find that the sharp transition is smeared out by additional interface scattering terms and the localization length behavior shows a smooth change from decreasing with the random strength at small to increasing at large . In both regions, the dependence of follows the same asymptotic behavior . Recently pseudospin-1 systems have been experimentally realized in photonic (25, 26, 34–37) and ultracold atom systems (33). Meanwhile, the applied potentials in such systems can be realized by uniformly scaling the structure in PCs (27) or manipulating an appropriate holographic mask in ultracold atom systems (28–32). Thus, it is experimentally feasible to prepare a 1D disordered pseudospin-1 system using such artificial structures. For a given randomness , two localization phases can be observed by tuning the incident energy from to .

Scalar Wave Equation

In this section, we derive the scalar wave equation for pseudospin-1/2 systems. For pseudospin-1/2 systems, in Eq. 2 is a 2D Pauli vector, i.e., with

| [S1] |

and the wave function is a two-component spinor function, , because for oblique incidence on the layered structure, the wavevector component parallel to the interface, , is conserved in each layer. Taking the operator as and , we can express Eq. 2 for pseudospin-1/2 systems as

| [S2] |

or

| [S3] |

| [S4] |

By eliminating in Eqs. S3 and S4, we obtain the following scalar wave equation for :

| [S5] |

We now define a new coordinate variable in the same way as that in pseudospin-1 systems, i.e., , and write and . Then, we can rewrite Eq. S5 as

| [S6] |

where is the interface in the coordinate with and for , and . Note that here in the coordinate is a piecewise constant function because the normalized potential is a constant in each layer. Thus, we have . In comparison with Eq. 7, the scalar wave equation, Eq. S6, for pseudospin-1/2 systems has additional interface scattering terms located at all interfaces.

Phase Accumulation and Reflection Amplitudes

In this section, we derive the phase accumulation between two interfaces and the reflection amplitudes at an interface. Inside the layer, Eqs. 7 and 8 can be simplified as

| [S7] |

with , for both pseudospin systems, where is the normalized potential in the layer. Eq. S7 is a wave equation in the coordinate with the wave number . Thus, the accumulated phase between the and interfaces of the sample is (), where is the thickness of the layer in the coordinate, derived from the coordinate transformation .

Now we derive the reflection amplitudes between the and layers. Consider two semiinfinite homogeneous media meeting at an interface at : On the left of the interface () is the normalized potential in the layer, and on the right () is in the layer. Suppose that () is the 1D Green’s function for each medium when it is infinite; then we can construct the Green’s function () in each semiinfinite medium in the presence of one interface (48) as follows:

| [S8] |

For pseudospin-1 systems, the Green’s functions should satisfy the following boundary conditions at the interface obtained from Eq. 7:

| [S9] |

| [S10] |

Here the dot over denotes the derivative with respect to the first argument. Solving Eqs. S9 and S10, we obtain

| [S11] |

for pseudospin-1 systems. Note that we have () for the homogeneous medium.

For pseudospin-1/2 systems, the Green’s functions obey different boundary conditions due to the interface scattering potentials in Eq. 8,

| [S12] |

| [S13] |

where . Thus, we can obtain the reflection amplitudes for pseudospin-1/2 systems,

| [S14] |

| [S15] |

For both systems, the Green’s function in the medium of the layer, , satisfies the following equation:

| [S16] |

By solving Eq. S16, we can obtain . Substituting into Eqs. S11, S14, and S15, we have

| [S17] |

for pseudospin-1 systems and

| [S18] |

| [S19] |

for pseudospin-1/2 systems.

Note that the reflection amplitudes obtained here from the SGF method are consistent with the results in ref. 27 calculated in the x coordinate by matching the boundary conditions.

Lyapunov Exponent in the Region of

In this section, we show the Lyapunov exponents for pseudospin-1 and - systems in the region of . In region , the reflection amplitudes for pseudospin-1 systems can be approximated as when . Note that is real for small , satisfying ; then we have , where . This indicates that does not contribute to shown in Eq. 12. Thus, in the limit of , can be approximated as

| [S20] |

where .

The determinant can be calculated using the Leibniz formula. The Leibniz formula for the determinant of a matrix is

| [S21] |

Here the sequence is one permutation of the set achieved by successively interchanging two entries times. For a matrix with all diagonal elements as 1, Eq. S21 can be written as a summation over a series of products with different numbers of off-diagonal elements,

| [S22] |

where the first term is the product of all diagonal elements for no interchange of the entries, the second term is the product of two off-diagonal elements for interchanging two entries once, and the third term is the product of three off-diagonal elements, etc. So for the matrix with the elements in Eq. 11 and , the determinant can be calculated to the lowest order of ,

| [S23] |

Here the phase factor with . So, for small the determinant can be written as

| [S24] |

where . Thus, we can obtain the following asymptotic behavior of in the limit of ,

| [S25] |

where and denotes the real part of . Then the Lyapunov exponent for the case can be obtained as

| [S26] |

Note that the Lyapunov exponent is proportional to (or ) in Eq. S26.

In the case of , we can further take a small expansion in the expression of and find

| [S27] |

Here the ensemble averages of , , , and are taken as and because and are independent random variables distributed uniformly in the range of . With the same approximation, can be written as

| [S28] |

In the case of , . Thus, in this limit, for the phase factor , we can obtain with . Thus, for ,

| [S29] |

Because , , , and are independent random variables for , we have

| [S30] |

Here

and

For , the phase factor is written as

| [S31] |

And the ensemble average of is expressed as follows:

| [S32] |

Here all ensemble averages are zero except . So we can obtain from Eq. S28 as

| [S33] |

Thus, we can get and the Lyapunov exponent from Eq. S26 for and small as

| [S34] |

Here .

For pseudospin-1/2 systems, the reflection amplitudes for and small can be approximated as

| [S35] |

Thus, for pseudospin-1/2 systems can be written as

| [S36] |

For in pseudospin-1/2 systems, it can also be obtained using the Leibniz formula in a way similar to that in pseudospin-1 systems,

| [S37] |

Thus, the Lyapunov exponent in pseudospin-1/2 systems can be expressed as follows:

| [S38] |

From Eqs. S34 and S38, we can see that the two pseudospin systems have different dependences of the Lyapunov exponent.

for Pseudospin-1 Systems in the Case

We first consider the term with . In the case of , is imaginary when and real when . Thus, we have

| [S39] |

Because the distribution of is uniform, we find

| [S40] |

for sufficiently small satisfying . Thus, does not have contributions to in the limit of and can be written as

| [S41] |

For convenience, we separate the integral space into the following nine parts:

-

i)

and :

| [S42] |

To calculate , we use the following variable substitutions:

| [S43] |

Then can be rewritten as follows:

| [S44] |

-

ii)

and :

| [S45] |

For small , i.e., , the first two leading terms of are

| [S46] |

-

iii)

and :

| [S47] |

Thus,

| [S48] |

At small , can be expressed as

| [S49] |

-

iv)

and or and :

| [S50] |

| [S51] |

Note that the integrands for and are symmetric after interchanging the variables and , and we have :

| [S52] |

For the last integral, we have

| [S53] |

where , , and . At small , and can be expressed as

| [S54] |

-

v)

and or and :

| [S55] |

| [S56] |

It is straightforward to show . After integration, can be expressed as

| [S57] |

At small , Eq. S57 gives

| [S58] |

-

vi)

and or and :

| [S59] |

| [S60] |

Also, we have . can be integrated as

| [S61] |

For small , Eq. S61 gives

| [S62] |

Summing over all these nine integrals, we obtain in pseudospin-1 systems,

| [S63] |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (Project AoE/P-02/12). S.G.L. also acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation under Grant DMR-1508412.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620313114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anderson PW. Absence of diffusion in certain random lattices. Phys Rev. 1958;109:1492–1505. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee PA, Ramakrishnan TV. Disordered electronic systems. Rev Mod Phys. 1985;57:287–337. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheng P. Scattering and Localization of Classical Waves in Random Media. World Scientific; Singapore: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soukoulis CM, Economou EN. Electronic localization in disordered systems. Waves Random Media. 1999;9:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer B, MacKinnon A. Localization: Theory and experiment. Rep Prog Phys. 1993;56:1469–1564. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz T, Bartal G, Fishman S, Segev M. Transport and Anderson localization in disordered two-dimensional photonic lattices. Nature. 2007;446:52–55. doi: 10.1038/nature05623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh P, et al. Photon transport enhanced by transverse Anderson localization in disordered superlattices. Nat Phys. 2015;11:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahini Y, et al. Anderson localization and nonlinearity in one-dimensional disordered photonic lattices. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:013906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.013906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian CS, Cheung SK, Zhang ZQ. Local diffusion theory for localized waves in open media. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:263905. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.263905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John S, Sompolinsky H, Stephen MJ. Localization in a disordered elastic medium near two dimensions. Phys Rev B. 1983;27:5592–5603. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloch I. Ultracold quantum gases in optical lattices. Nat Phys. 2005;1:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soukoulis CM, Kafesaki M, Economou EN. Negative-index materials: New frontiers in optics. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1941–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novoselov KS, et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro Neto AH, Guinea F, Peres NMR, Novoselov KS, Geim AK. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev Mod Phys. 2009;81:109–162. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asatryan AA, et al. Suppression of Anderson localization in disordered metamaterials. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99:193902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.193902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogilevtsev D, Pinheiro FA, dos Santos RR, Cavalcanti SB, Oliveira LE. Suppression of Anderson localization of light and Brewster anomalies in disordered superlattices containing a dispersive metamaterial. Phys Rev B. 2010;82:081105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Herrera EJ, Izrailev FM, Markarov NM. Non-conventional Anderson localization in bilayered structures. Europhys Lett. 2012;98:27003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi SK, Park CH, Louie SG. Electron supercollimation in graphene and Dirac Fermion materials using one-dimensional disorder potentials. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;113:026802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.026802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu SL, Zhang DW, Wang ZD. Delocalization of relativistic Dirac particles in disordered one-dimensional systems and its implementation with cold atoms. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:210403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.210403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasan MZ, Kane CL. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev Mod Phys. 2010;82:3045–3067. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi XL, Zhang SC. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev Mod Phys. 2011;83:1057–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X. Observing Zitterbewegung for photons near the Dirac point of a two-dimensional photonic crystal. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:113903. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.113903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakoda K. Dirac cone in two- and three-dimensional metamaterials. Opt Express. 2012;20:3898–3917. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.003898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mei J, Wu Y, Chan CT, Zhang ZQ. First-principles study of Dirac and Dirac-like cones in phononic and photonic crystals. Phys Rev B. 2012;86:035141. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang XQ, Lai Y, Hang ZH, Zheng H, Chan CT. Dirac cones induced by accidental degeneracy in photonic crystals and zero-refractive-index materials. Nat Mater. 2011;10:582–586. doi: 10.1038/nmat3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moitra P, et al. Realization of an all-dielectric zero-index optical metamaterial. Nat Photon. 2013;7:791–795. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang A, Zhang ZQ, Louie SG, Chan CT. Klein tunneling and supercollimation of pseudospin-1 electromagnetic waves. Phys Rev B. 2016;93:035422. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen R, Shao LB, Wang B, Xing DY. Single Dirac cone with a flat band touching on line-centered-square optical lattices. Phys Rev B. 2010;81:041410. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juzeliunas G, Ruseckas J, Dalibard J. Generalized Rashba-Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling for cold atoms. Phys Rev A. 2010;81:053403. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban DF, Bercioux D, Wimmer M, Hausler W. Barrier transmission of Dirac-like pseudospin-one particles. Phys Rev B. 2011;84:115136. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dora B, Kailasvuori J, Moessner R. Lattice generalization of the Dirac equation to general spin and the role of the flat band. Phys Rev B. 2011;84:195422. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y, Jin G. Omnidirectional transmission and reflection of pseudospin-1 Dirac fermions in a Lieb superlattice. Phys Lett A. 2014;378:3554–3560. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taie S, et al. Coherent driving and freezing of bosonic matter wave in an optical Lieb lattice. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1500854. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guzman-Silva D, et al. Experimental observation of bulk and edge transport in photonic Lieb lattices. New J Phys. 2014;16:063061. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee S, et al. Observation of a localized flat-band state in a photonic Lieb lattice. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:245504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.245504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vicencio RA, et al. Observation of localized states in Lieb photonic lattices. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:245503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.245503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diebel F, Leykam D, Kroesen S, Denz C, Desyatnikov AS. Conical diffraction and composite Lieb bosons in photonic lattices. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;116:183902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.183902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu HY, Lai YC. Revival resonant scattering, perfect caustics, and isotropic transport of pseudospin-1 particles. Phys Rev B. 2016;94:165405. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bliokh YP, Freilikher V, Savelev S, Nori F. Transport and localization in periodic and disordered graphene superlattices. Phys Rev B. 2009;79:075123. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abedpour N, Esmailpour A, Asgari R, Reza Rahimi Tabar M. Conductance of a disordered graphene superlattice. Phys Rev B. 2009;79:165412. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Q, Gong J, Muller CA. Localization behavior of Dirac particles in disordered graphene superlattices. Phys Rev B. 2012;85:104201. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEuen PL, Bockrath M, Cobden DH, Yoon YG, Louie SG. Disorder, pseudospins, and backscattering in carbon nanotubes. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;83:5098–5101. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ando T, Nakanishi T, Saito R. Berry’s phase and absence of back scattering in carbon nanotubes. J Phys Soc Jpn. 1998;67:2857–2862. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sipe JE, Sheng P, White BS, Cohen MH. Brewster anomalies: A polarization-induced delocalization effect. Phys Rev Lett. 1988;60:108–111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bliokh KY, Freilikher VD. Localization of transverse waves in randomly layered media at oblique incidence. Phys Rev B. 2004;70:245121. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tworzydlo J, Trauzettel B, Titov M, Rycerz A, Beenakker CWJ. Sub-poissonian shot noise in graphene. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:246802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.246802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sepkhanov RA, Bazaliy YB, Beenakker CWJ. Extremal transmission at the Dirac point of a photonic band structure. Phys Rev A. 2007;75:063813. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aronov AG, Gasparian VM, Gummich U. Transmission of waves through one-dimensional random layered systems. J Phys Condens Matter. 1991;3:3023–3039. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kappus M, Wegner F. Anomaly in the band center of the one-dimensional Anderson model. Z Phys B Con Mat. 1981;45:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Tiggelen BA, Tip A. Photon localization in disorder-induced periodic multilayers. J Phys I France. 1991;1:1145–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crisanti A. Resonances in random binary optical media. J Phys A Math Gen. 1990;23:5235–5240. [Google Scholar]