Significance

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethal genetic disorder caused by a lack of dystrophin protein. Cardiomyopathy is a leading cause of death in DMD. Although exon skipping with antisense morpholino oligonucleotides is very promising, morpholino-mediated exon skipping has induced barely detectable dystrophin levels in the hearts of DMD animal models. Here, we show that systemic multiexon skipping using a cocktail of peptide-conjugated morpholinos (PPMOs) rescued dystrophin expression in the myocardium and cardiac Purkinje fibers in a dystrophic dog model. The treatment reduced vacuole degeneration in Purkinje fibers and improved electrocardiogram abnormalities without apparent toxicity. These results indicate that PPMO-mediated multiexon skipping is a therapeutic approach for treating cardiac conduction abnormalities in DMD.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, exon skipping, peptide-conjugated morpholinos, cardiac Purkinje fibers, dystrophic dog model

Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethal genetic disorder caused by an absence of the dystrophin protein in bodywide muscles, including the heart. Cardiomyopathy is a leading cause of death in DMD. Exon skipping via synthetic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) represents one of the most promising therapeutic options, yet PMOs have shown very little efficacy in cardiac muscle. To increase therapeutic potency in cardiac muscle, we tested a next-generation morpholino: arginine-rich, cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated PMOs (PPMOs) in the canine X-linked muscular dystrophy in Japan (CXMDJ) dog model of DMD. A PPMO cocktail designed to skip dystrophin exons 6 and 8 was injected intramuscularly, intracoronarily, or intravenously into CXMDJ dogs. Intravenous injections with PPMOs restored dystrophin expression in the myocardium and cardiac Purkinje fibers, as well as skeletal muscles. Vacuole degeneration of cardiac Purkinje fibers, as seen in DMD patients, was ameliorated in PPMO-treated dogs. Although symptoms and functions in skeletal muscle were not ameliorated by i.v. treatment, electrocardiogram abnormalities (increased Q-amplitude and Q/R ratio) were improved in CXMDJ dogs after intracoronary or i.v. administration. No obvious evidence of toxicity was found in blood tests throughout the monitoring period of one or four systemic treatments with the PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection). The present study reports the rescue of dystrophin expression and recovery of the conduction system in the heart of dystrophic dogs by PPMO-mediated multiexon skipping. We demonstrate that rescued dystrophin expression in the Purkinje fibers leads to the improvement/prevention of cardiac conduction abnormalities in the dystrophic heart.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common lethal myopathy, and is characterized by progressive muscle degeneration and weakness (1). Patients typically die around 20–30 y of age because of cardiac and/or respiratory failure. DMD is caused by a lack of dystrophin protein due to mutations in the dystrophin gene (2). Exon skipping using a splice-switching oligonucleotide (SSO) is one of the most promising therapies for DMD and is currently the focus of clinical trials (3). SSO-mediated exon skipping prevents the incorporation of mutated exons and/or neighboring exons into the spliced mRNA and restores its reading frame (4). As a result, internally deleted but partly functional dystrophin protein is produced from the modified mRNA, similar to what is observed in the milder dystrophinopathy, Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) (5, 6).

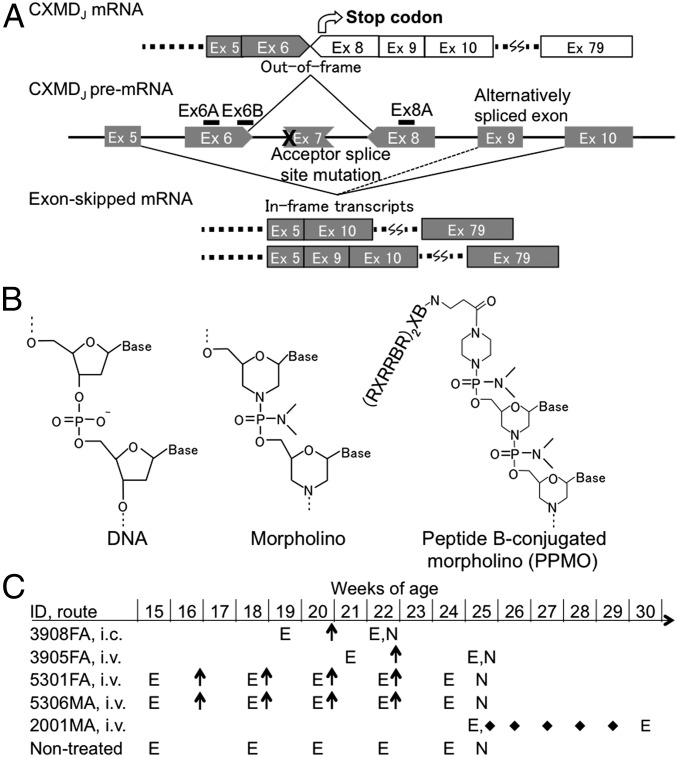

Therapeutic exon skipping that targets a single exon is applicable to 64% of all DMD patients (7). Multiexon skipping can potentially increase the scope of SSO therapy to ∼90% of deletion mutations, 80% of duplication mutations, and 98% of nonsense mutations (8, 9). In some cases, efficient exon skipping is induced using a few SSOs targeting different positions in the same exon (10, 11). Thus, SSOs need to be designed according to mutation patterns and/or the nature of the target exon. Golden Retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) and beagle-based canine X-linked muscular dystrophy in Japan (CXMDJ), in which the dystrophin reading frame can be restored by skipping exons 6 and 8 (Fig. 1A), are widely accepted as adequate animal models to examine the potential of multiexon skipping (12). Previously, we demonstrated that a cocktail of SSOs targeting exons 6 and 8 efficiently induced multi-exon skipping and rescued dystrophin expression in bodywide skeletal muscles (10).

Fig. 1.

Therapeutic strategy with multiple exon skipping using the 3-PPMO cocktail in CXMDJ dogs. (A) The splice site mutation and design of splice-switching oligonucleotides (Ex6A, 6B, and Ex8A) for simultaneous skipping of exons 6 and 8. Exon 7 is spontaneously spliced out due to the mutation. (B) PPMO chemistry with peptide B sequence: B, β-alanine; R, l-arginine; X, 6-aminohexanoic acid. (C) Schematic outline of PPMO or unmodified PMO treatment in affected dogs. E, electrocardiogram; FA, female-affected; i.c., intracoronary artery injection; i.v., i.v. injection; MA, male-affected; N, necropsy; arrows, injections of a 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection, 4 mg/kg each); diamonds, injections of a 3-ummodified PMO cocktail (120 mg/kg/injection, 40 mg/kg each).

Although antisense phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) effectively rescued dystrophic phenotypes in murine and canine models and were well tolerated in patients enrolled in clinical trials (3), they were inefficient in cardiac muscles (10, 13). Only minuscule levels of rescued dystrophin protein have been reported in dystrophin-deficient hearts of animal models following exon skipping using unmodified morpholinos. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene therapy has enabled induction of minidystrophin in the heart of a dystrophic dog model (14, 15). As another promising solution, PMOs conjugated with cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have been developed to induce dystrophin expression more effectively in bodywide muscles including the heart (16–19). However, it is still unclear if cardiac conduction abnormalities as detected by electrocardiography (ECG) in DMD patients can be improved by the rescue of dystrophin expression in the heart. Although dystrophic mouse models show few cardiac abnormalities (20), dystrophic dog models, particularly CXMDJ dogs, manifest obvious cardiac symptoms, including distinct Q-waves and increased Q/R ratio, which indicate a cardiac conduction abnormality, in ECG (21), and vacuole degeneration in cardiac Purkinje fibers by 4 mo of age (22). We report here that systemic treatment with a cocktail of peptide-conjugated morpholinos (PPMOs) (18) (Fig. 1 B and C) results in successful skipping of multiple targeted exons, which restores expression of dystrophin protein in both skeletal and cardiac muscles in dystrophic dogs and ameliorates cardiac conduction defects. Blood tests indicate no obvious evidence of toxicity during follow-up of systemic treatment with one or four i.v. injections of the PPMO cocktail.

Results

Intramuscular Injection of the 3-PPMO Cocktail into Skeletal Muscle of the CXMDJ Dog.

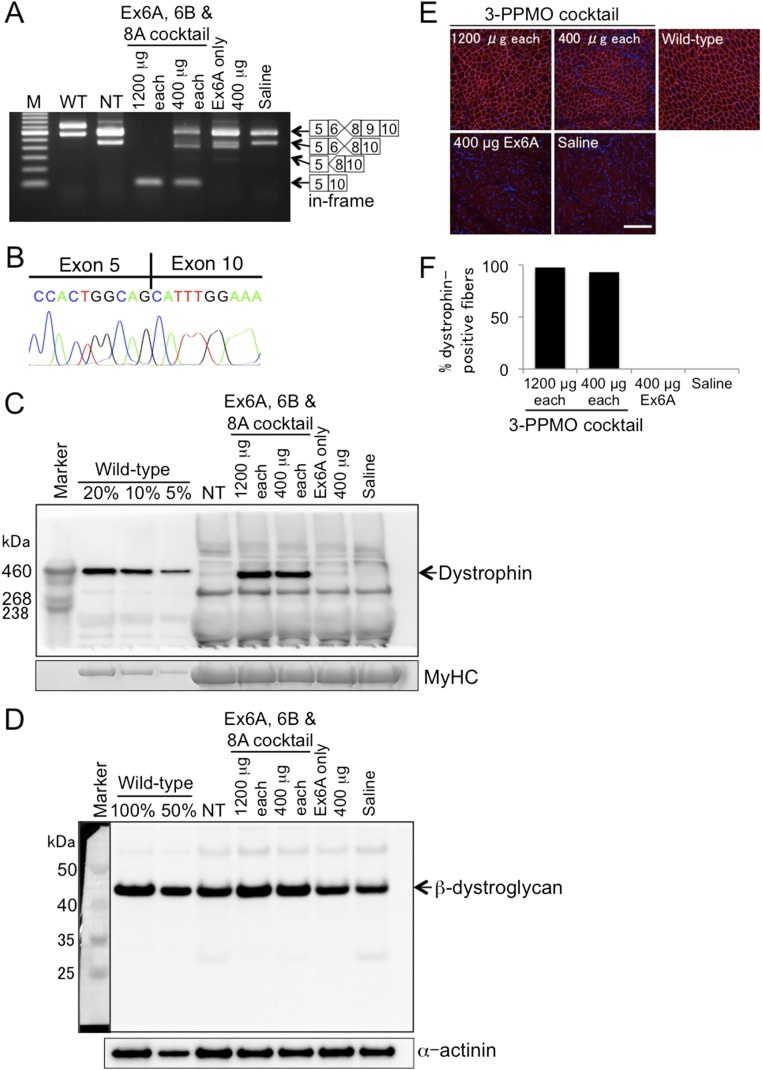

The efficacy of the 3-PPMO cocktail (Ex6, Ex6B, and Ex8A) to skip exons 6 and 8 was initially tested by a single intramuscular injection into the cranial tibialis muscles of CXMDJ dogs (Fig. S1): dogs 3908 female-affected (FA) and 3905FA were intramuscularly treated with 3-PPMOs and negative controls of either Ex6A only or saline, respectively. Two weeks after injection with a total of either 3,600 μg or 1,200 μg of the cocktail PPMOs (i.e., 1,200 μg or 400 μg of Ex6A, Ex6B, and Ex8A each, respectively), high-efficiency skipping of exons 6 and 8 was induced as shown by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. S1A). Removal of exons 6 and 8 was confirmed by sequencing of the PCR product (Fig. S1B). Western blotting demonstrated that intramuscular injection with the PPMO cocktail effectively rescued dystrophin protein expression, accompanied by increased levels of a dystrophin-associated protein, β-dystroglycan (Fig. S1 C and D). In immunohistochemistry, extensive expression of dystrophin-positive fibers (more than 93%) was observed in the CXMDJ dog (3908FA) after treatment with both doses (Fig. S1 E and F).

Fig. S1.

Local restoration of dystrophin expression in the cranial tibialis (CT) muscle of CXMDJ dogs 2 wk after intramuscular (i.m.) injection with PPMO(s). A 3-PPMO cocktail (1,200 or 400 μg of each PPMO) was injected into the left or right CT muscle, respectively, of dog 3908FA. Left and right CT muscles of dog 3905FA were used for i.m. injection of a control Ex6A PPMO at 400 μg and saline, respectively. (A) Efficacy of exons 6 and 8 skipping with PPMO(s): Ex6A, Ex6B, and Ex8A in RT-PCR. Exon 9 is spontaneously spliced out along with exons 6 and 8 skipping in the CXMDJ dog model without affecting the reading frame. M, 100-bp ladder; NT, nontreated; WT, wild type. (B) Sequencing of the exons 6 and 8-skipped transcript. (C) Western blotting using the anti-dystrophin C-terminal antibody. Forty micrograms of protein was loaded for NT and treated dog muscle samples. For WT dog muscle samples, 8, 4, and 2 μg of protein, which represent 20, 10, and 5% of the amount of the treated dog muscles, respectively, were loaded to serve as positive controls. MyHC on a posttransferred gel is shown as a loading control. (D) Detection of β-dystroglycan in the intramuscularly treated skeletal muscle lysate by Western blotting. Four micrograms of protein was loaded for wild-type, NT, and treated CT muscle samples (50% in wild type represents 2 μg of the protein lysate). α-Actinin was detected as a loading control. An inset image showing the marker used for the blot, taken by colorimetric detection, is included for band size reference. (E) Immunohistochemistry with the anti-dystrophin rod domain antibody. Representative images are shown from at least three sections at 100-μm intervals. Red, dystrophin; blue, nuclei counterstained with DAPI. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (F) Percentage of dystrophin-positive fibers as shown by immunohistochemistry.

A Single Intracoronary Artery or i.v. Injection of the 3-PPMO Cocktail.

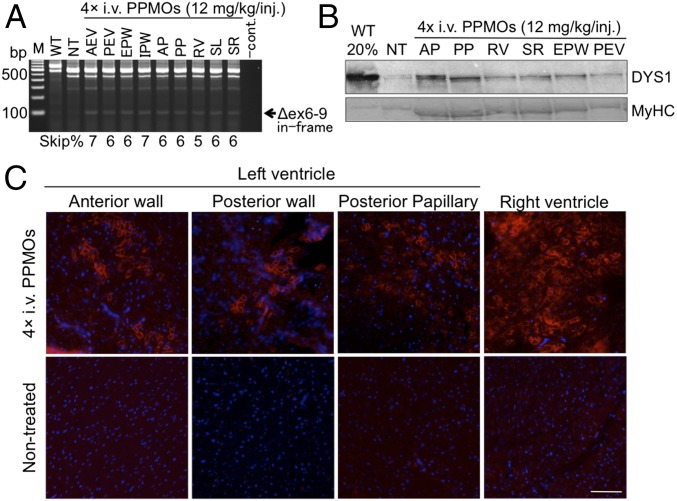

To examine whether dystrophin expression can be induced in cardiac muscles by multiple exon skipping, we injected the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg total, 4 mg/kg each of Ex6A, Ex6B, and Ex8A) into two CXMDJ dogs (ID no. 3908FA and 3905FA) at 5 mo of age through two different administration routes: (i) intracoronary artery (i.c.) and (ii) i.v. injections, respectively. Two weeks after a single injection via either route, exons 6–9 skipped in-frame dystrophin transcripts were observed in cardiac muscles (Fig. 2 A and B). Western blotting analysis revealed increased expression levels of rescued dystrophin protein in most areas of the heart following single-dose treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail (Fig. 2 C and D).

Fig. 2.

Multiexon skipping and rescued dystrophin in the heart of CXMDJ dogs after a single i.c. or i.v. injection with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg total, 4 mg/kg each PPMO). (A and B) Exons 6–9 skipped dystrophin transcripts in the heart of the CXMDJ dog model treated with a single i.c. or i.v. injection, respectively. Exon 9 is spontaneously spliced out along with exons 6 and 8 skipping without affecting the reading frame. Western blotting with the anti-dystrophin rod domain antibody (DYS1) shows dystrophin restoration in the dystrophic heart following one i.c. (C) or i.v. (D) treatment with the 3-PPMOs. Forty micrograms of protein was loaded for nontreated (NT) and treated dog muscle samples. In wild-type (WT) dogs, 8 μg (20%) of protein was loaded as a positive control. Anti-desmin antibody was used as a loading control. Positive bands in NT dog samples indicate revertant fiber-derived dystrophin expression. AEV, anterior external area of the left ventricle (LV); AP, anterior papillary; EPW, endocardial surface of the posterior wall of LV; IPW, inferoposterior wall of LV; PEV, posterior external area of LV; PP, posterior papillary; RV, right ventricle; SL, the left side of the interventricular septum (IVS); SR, the right side of IVS.

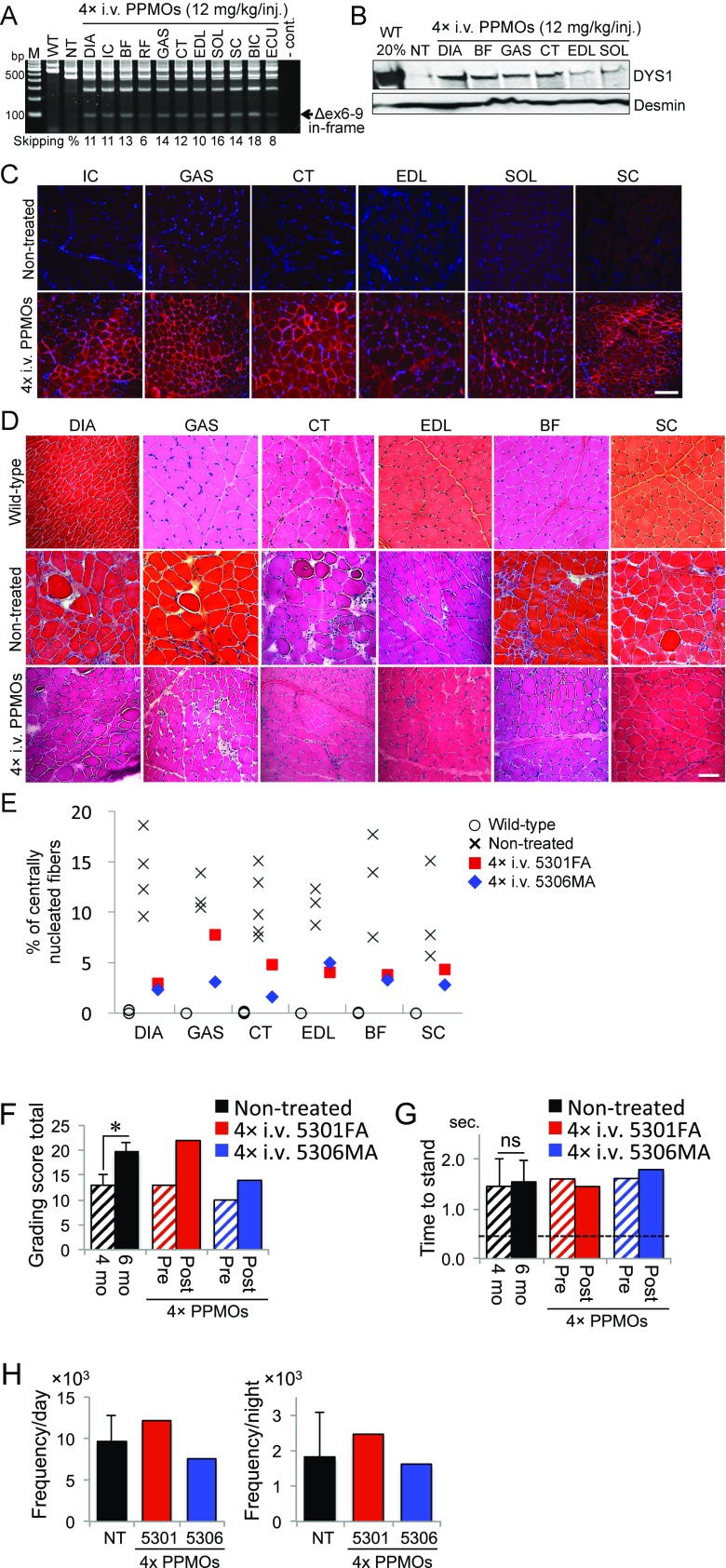

Efficacy of Four Consecutive Systemic Treatments with the 3-PPMO Cocktail in Skeletal Muscles.

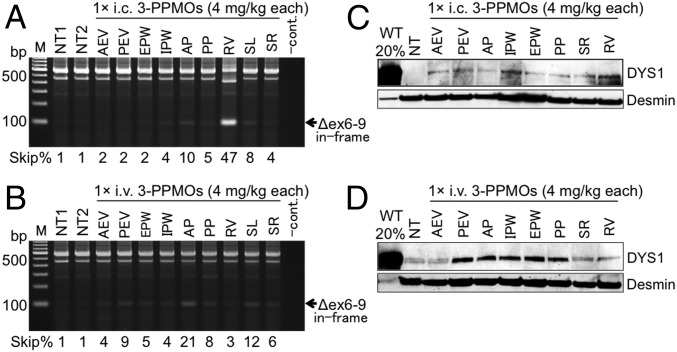

To examine the systemic effects of extended treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail, we intravenously injected 12 mg/kg total PPMO (4 mg/kg each PPMO) into two CXMDJ dogs [ID no. 5301FA and 5306 male-affected (MA)] four times at 2-wk intervals. RT-PCR analysis revealed expression of in-frame dystrophin mRNA, in which exons 6–9 were skipped, in skeletal muscles of the affected dogs after consecutive i.v. treatments with the 3-PPMO cocktail (Fig. S2A). An increase in dystrophin protein levels (∼5% of the wild-type dog) was confirmed in most skeletal muscles of the treated dogs by Western blotting (Fig. S2B). In immunohistochemistry, extensive expression of dystrophin-positive fibers was observed throughout skeletal muscles after systemic treatment with the PPMO cocktail (Fig. S2C). The number of centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs) present in muscle tissue, indicative of cycles of muscle degeneration and regeneration, was examined by hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining. Although the percentage of CNFs in wild-type dogs was a mean 0.05% ± 0.07 (SD) with six skeletal muscle types tested (n = 3–5 for each type), affected dogs had CNFs at 11.3% ± 1.4% on average with the six muscle types. A reduced percentage of CNFs was observed in most areas of skeletal muscles in PPMO-treated dogs (Fig. S2 D and E): mean 4.6% ± 1.5% and 3.0% ± 1.0% in six tested skeletal muscle types of dogs 5301FA and 5306MA, respectively. However, no improvement in the clinical grading or muscle function was observed in the treated dogs (Fig. S2 F and G). Spontaneous locomotor activity showed no apparent change in treated dogs compared with nontreated affected dogs over 5 d/nights 1 wk after the final injection (Fig. S2H).

Fig. S2.

Effects of four i.v. injections with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection) on skeletal muscles of CXMDJ dogs. (A) In-frame exons 6–9 skipped dystrophin transcripts after systemic treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail. BF, biceps femoris; BIC, biceps brachii; CT, cranial tibialis; DIA, diaphragm; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; GAS, gastrocnemius; IC, intercostal; M, 100-bp ladder; NT, nontreated CXMDJ dogs; RF, rectus femoris; SC, sternocleidomastoid; SOL, soleus; WT, wild type. (B) Western blotting with the anti-dystrophin NCL-DYS1 antibody. Anti-desmin antibody was used as a loading control. Forty or eight (20%) μg of protein from CXMDJ and WT dogs, respectively, was loaded. (C) Immunohistochemistry with the NCL-DYS1 antibody (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Representative data are shown from two treated CXMDJ dogs. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (D) H&E staining. Representative data are shown. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (E) Percentage of centrally nucleated fibers (n = 3–5 in wild-type and nontreated affected dogs). (F) Clinical grading score. Higher values represent more severe phenotype. Mean ± SD in nontreated affected dogs (n = 3). (G) Results from timed function tests from lateral recumbency to standing. Mean ± SD in nontreated affected dogs (n = 12). A statistical test was performed with paired t test: *P < 0.05. ns, no significant difference. In F and G, hatched bars indicate 4 mo of age in NT and pretreated dogs. Solid bars represent 6 mo of age in NT and posttreated dogs 2 wk after the final injection. The dashed line in G indicates the average time obtained with seven WT dogs at 6 mo of age. (H) Locomotion frequency in NT dogs (n = 3, mean ± SD) and treated dogs with four i.v. injections. The frequency per day or night was counted for 5 d 1 wk after the final injection.

Restoration of Dystrophin Expression in Myocardium After Four Systemic Administrations of the 3-PPMO Cocktail.

Exons 6–9 skipped in-frame dystrophin transcripts were detected in most areas of the cardiac muscle in consecutively treated CXMDJ dogs 5301FA and 5306MA (Fig. 3A). Western blotting analysis revealed increased levels of dystrophin protein with a molecular weight of ∼400 kDa in the heart (∼5% dystrophin protein compared with that of the wild-type dog) (Fig. 3B). In immunohistochemistry, scattered dystrophin-positive fibers were extensively observed in the working myocardium 2 wk after the final i.v. injection (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Recovery of dystrophin expression in working myocardium 2 wk after four i.v. injections of the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/i.v.) into CXMDJ dogs (5301FA and 5306MA). (A) The efficiency of exons 6–9 skipping in the cardiac tissues. (B) Western blotting following four i.v. injections at 2-wk intervals. Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) on a posttransferred gel is shown as a loading control. (C) Immunohistochemistry with the NCL-DYS1 antibody (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 100 μm.) Representative images are shown.

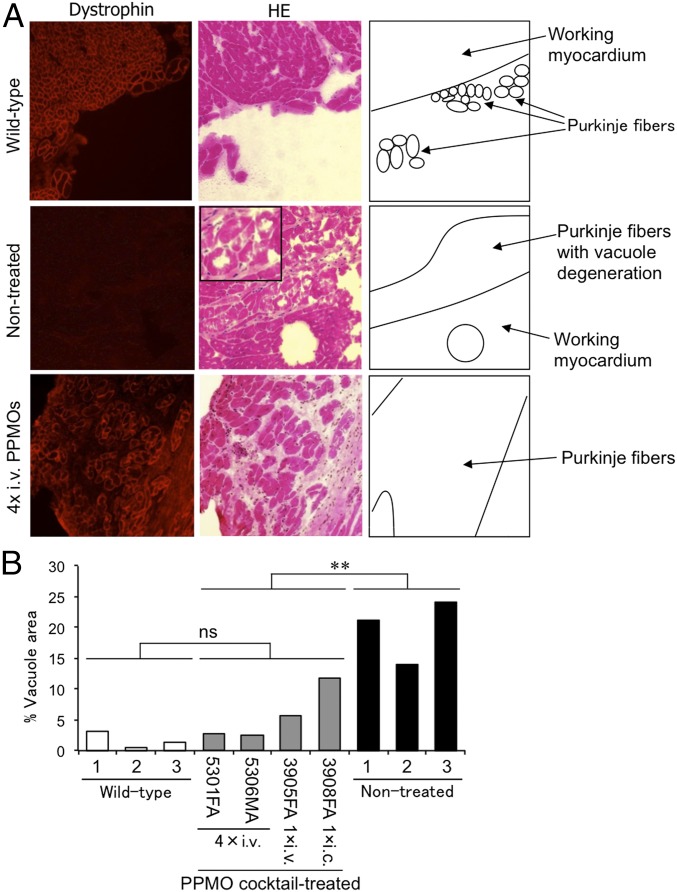

Recovery of Dystrophin Expression and Amelioration of Vacuole Degeneration in Cardiac Purkinje Fibers in CXMDJ Dogs.

CXMDJ dogs have been reported to exhibit vacuole degeneration in cardiac Purkinje fibers, a histopathological finding also seen in DMD patients (22–24). We examined whether rescued dystrophin expression can ameliorate vacuole degeneration in CXMDJ dogs. Cardiac Purkinje fibers were identified as having a larger diameter and fainter stainability compared with working myocardium, as observed on transverse sections following H&E staining, as previously described (22). Immunohistochemistry and H&E staining of serial sections revealed reduced vacuole degeneration in cardiac Purkinje fibers, which was accompanied by the recovery of dystrophin expression in the same fibers, of the systemically treated CXMDJ dogs (ID nos. 5301FA and 5306MA), whereas large and many vacuoles were observed in Purkinje fibers of nontreated CXMDJ dogs (Fig. 4A). In all regimens tested, amelioration of vacuole degeneration in Purkinje fibers was found in all four treated CXMDJ dogs, and a statistically significant difference in the vacuole areas was found between treated and nontreated dog groups (Fig. 4B). In the heart of nontreated CXMDJ dogs, degenerative vacuole areas of up to 24% of cardiac Purkinje fiber regions were observed. After a single administration of the PPMO cocktail through i.c. or i.v. injection, the area of vacuole degeneration was reduced to ∼13% and 7%, respectively. In the two CXMDJ dogs subjected to four systemic injections at 2-wk intervals with the 3-PPMO cocktail, we observed amelioration of degenerative Purkinje fibers to less than 3% of the vacuole area, comparable to the vacuole area in wild-type dogs.

Fig. 4.

Ameliorated histology of cardiac Purkinje fibers in dystrophic dogs 2 wk after a single injection or four systemic injections with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection). (A) Dystrophin expression by immunohistochemistry (Left panels) and H&E staining (Middle panels) with serial sections and drawn schemes of the Purkinje fibers (Right panels). Purkinje fibers are shown in the peripheral area of the cardiac muscle tissue with faint stainability in H&E staining. (Inset) A magnified instance of vacuole degeneration in nontreated dogs. Representative images with the four i.v.-treated CXMDJ dogs and nontreated affected dogs are shown. (B) The relative area of vacuole degeneration in cardiac Purkinje fibers after PPMO treatment by i.c. or i.v. injection. ns, no significant difference. **P < 0.01 between treated and nontreated groups (Student’s t test).

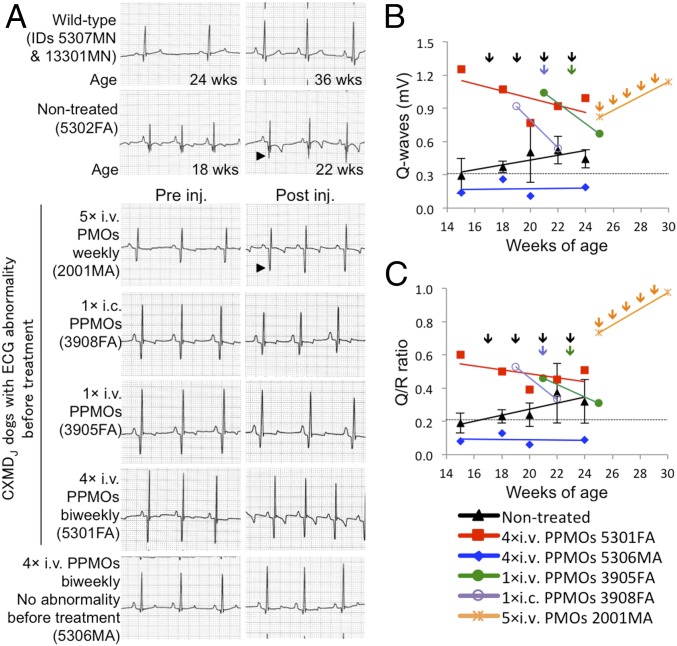

Amelioration of Cardiac Conduction Abnormalities in CXMDJ Dogs After Treatment with the 3-PPMO Cocktail.

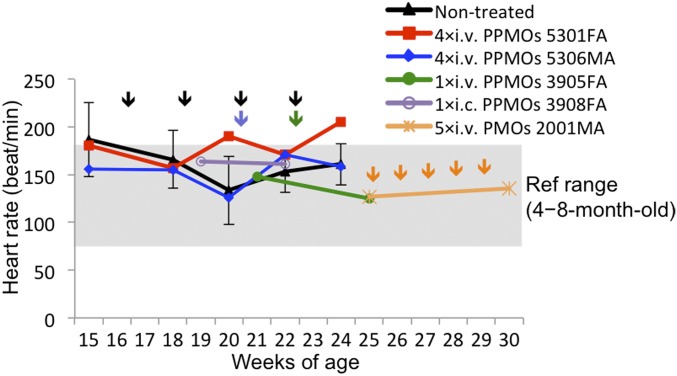

Cardiac conduction disturbance in CXMDJ and GRMD dogs becomes clinically evident using ECG, demonstrated by deep and narrow Q-waves, which are reported in DMD patients (21, 25–27). The dystrophic dog models have also been reported to manifest increased Q/R ratio as an outcome of impaired cardiac function (21, 25). To assess recovery of the cardiac conduction system after treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg each), ECG with lead II was analyzed in CXMDJ dogs before and after the single i.v. or i.c. injection or after the four i.v. injections at 2-wk intervals. A peak of distinct Q-waves and a high Q/R ratio outside the normal range were observed by 4 mo of age in nontreated dogs and three dogs subjected to treatment; therefore, injection with the PPMO or PMO cocktail was initiated at 4–5 mo of age. ECG abnormalities (deep Q-amplitude and Q/R ratio) were confounded in the control dog systemically treated with 3-unmodified PMO cocktail (120 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg each) even after five weekly injections (Fig. 5 A and B). In contrast, abnormal ECG findings were improved in three treated CXMDJ dogs that manifested abnormal ECG before the treatment: dog 3908FA by 1× i.c., dog 3905FA by 1× i.v., and dog 5301FA by 4× i.v. The Q-amplitude and Q/R ratio of the CXMDJ dog 5306MA, which did not manifest ECG abnormality before the treatment, remained in the normal range 2 wk after the final injection. In echocardiography (echo) tests, no abnormal findings were found in left ventricular size, shape, and contractility in the hearts of all four dogs before treatment compared with reference values (21, 28): left ventricular internal diameter (LVID) in diastole (LVIDd), 24.1 mm ± 3.4 (SD); LVID in systole (LVIDs), 14.1 mm ± 1.8; interventricular septum thickness in diastole (IVSd), 5.6 mm ± 0.9; interventricular septum thickness in systole (IVSs), 9.1 mm ± 1.4; left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (LVPWd), 5.3 mm ± 0.7; left ventricular posterior wall thickness in systole (LVPWs), 8.6 mm ± 1.7; and fractional shortening (FS), 40.7% ± 7.4. Consistent with our previous study reporting that echo abnormalities become evident from around 21 mo of age (21), the measured values of those items in the two dogs after four PPMO injections were also in the normal range: LVIDd, 24.5 mm ± 0.7; LVIDs, 14.7 mm ± 0.5; IVSd, 6.5 mm ± 0.7; IVSs, 10.0 mm ± 1.4; LVPWd, 7.5 mm ± 0.7; LVPWs, 10.5 mm ± 0.7; and FS, 37.0% ± 1.4. Obvious abnormality in heart rate was not observed in all PPMO-treated dogs during the course of monitoring (Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

Electrocardiogram changes after treatment with 3-PPMO cocktail at 12 mg/kg/injection. (A) Electrocardiogram in CXMDJ dogs 2 wk pre- and posttreatment with the PPMO cocktail by a single i.c. or i.v. injection, and by four consecutive i.v. injections. Arrowheads indicate an increase in Q-amplitude. Paper speed, 50 mm/s. Changes of Q-waves (B) and Q/R ratio (C) by treatment with the cocktail of PPMOs. Three nontreated affected dogs (mean ± SEM) and one affected dog i.v.-treated with the 3-unmodified PMO cocktail (120 mg/kg in total) five times at 1-wk intervals are shown as negative controls. Colored lines indicate linear approximations of the plots. Dotted lines indicate the average values observed in wild-type dogs (n = 6).

Fig. S3.

Heart rate monitoring in CXMDJ dogs during systemic treatment with i.v. injections of either the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection) or the unmodified 3-PMO cocktail (120 mg/kg/injection). The reference heart rate range was obtained from healthy beagle dogs at 4–8 mo of age tested here and in previous literature (42).

Toxicology.

Blood tests examining possible side effects of the 3-PPMO cocktail (total 12 mg/kg, i.v.) showed no obvious abnormalities related to hepatic or renal damage, electrolyte imbalance, or anemia due to systemic treatment in all dogs tested: dogs 5301FA and 5306MA were subjected to four i.v. injections and dog 3905FA was treated with a single i.v. injection (Fig. S4). A transient increase in some hepatic indicators (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) was observed in dog 5301FA; total bilirubin was also transiently increased in dog 5306MA. However, levels of a more specific indicator of liver damage, gamma-glutamyltransferase, were less than 3 IU/L within the normal range (0–10 IU/L in healthy beagle dogs at <1 y of age) throughout the monitoring period of all i.v.-treated dogs (29). Transiently elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, indicative of renal damage, were detected in dog 5306MA following the second i.v. injection, but that was reduced after the third injection. No obvious reduction of creatine kinase levels was observed in the treated CXMDJ dogs.

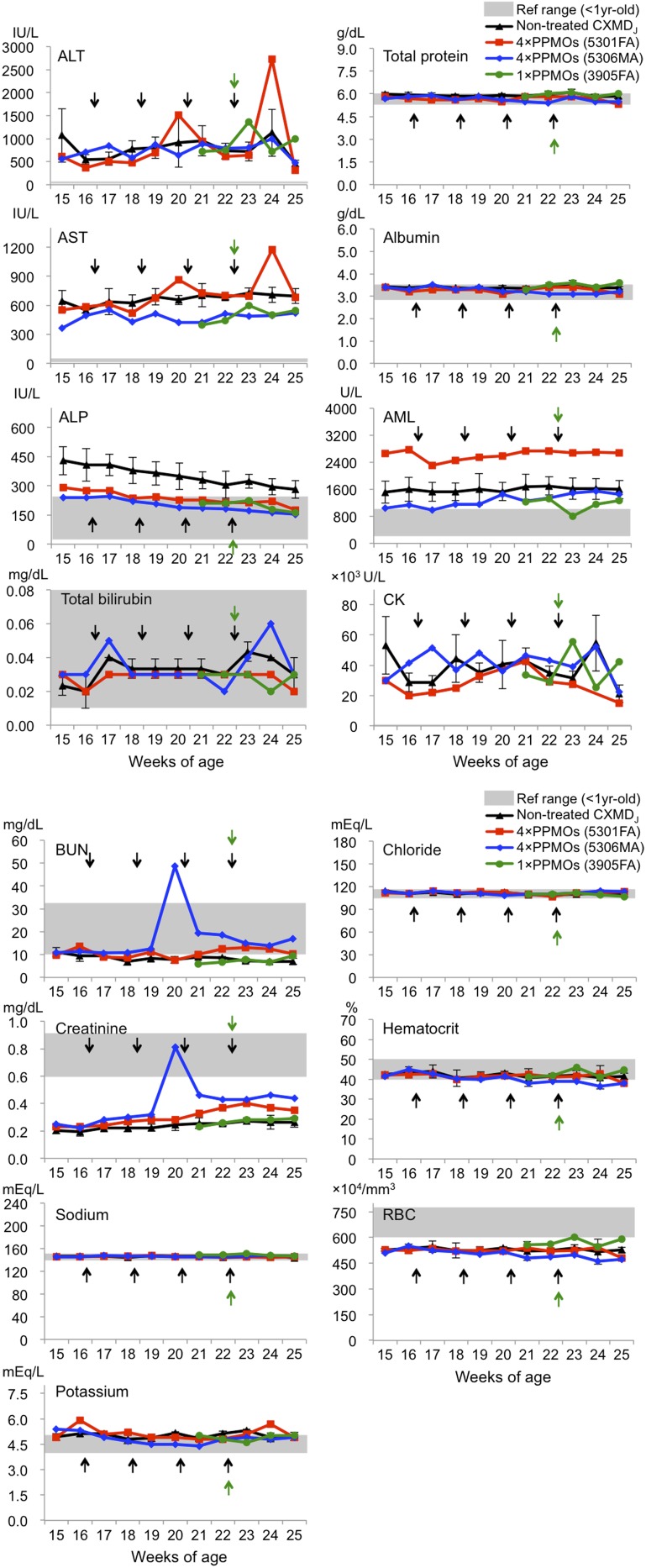

Fig. S4.

Blood tests during systemic treatment of the 3-PPMO cocktail with a total dose of 12 mg/kg/injection (4 mg/kg each). Serum samples prepared pre- and postinjection (24 h, 1 wk, and 2 wk later) were analyzed. The point immediately after an arrow indicates a serum sample collection 24 h after the injection. The levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, total protein, albumin, amylase (AML), creatine kinase (CK), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, sodium, potassium, chloride, hematocrit, and red blood cell (RBC) number were examined in nontreated and i.v.-treated dogs. Reference values highlighted in gray were set with values characteristic of healthy beagle dogs at <1 y of age obtained from the present study and previous literature (43, 44), except AML (45). Nontreated CXMDJ dogs (n = 3), mean ± SD.

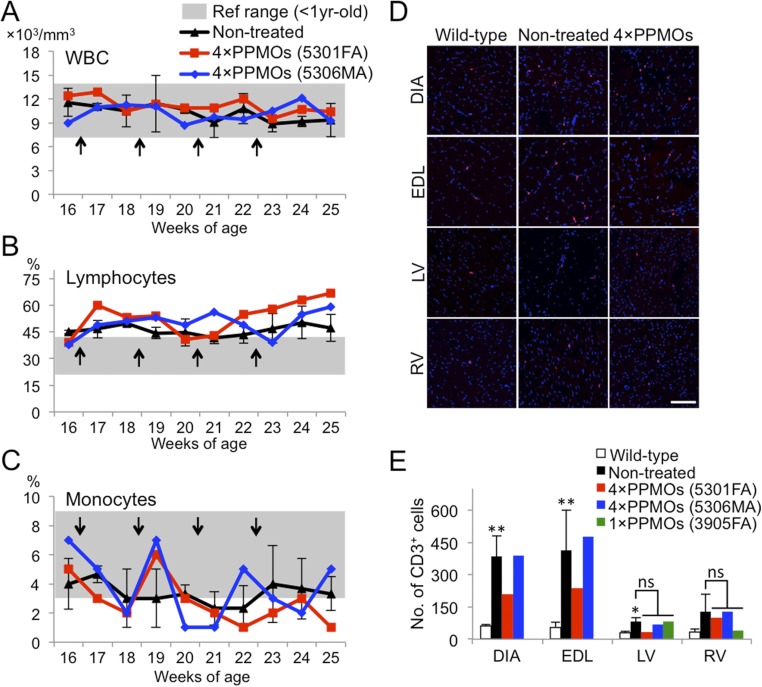

As peptides have the potential to become antigens, we examined the susceptibility of the 3-PPMO cocktail to cause immune activation by counting leukocyte numbers in systemically treated dogs. During systemic treatment, the number of white blood cells, leukocytes, and monocytes did not show any apparent changes with PPMO injection frequency (Fig. S5 A–C). The number of CD3-positive T leukocytes as detected by immunohistochemistry was also not obviously altered in both skeletal and cardiac muscles of three i.v.-treated dogs 2 wk after the injection compared with the nontreated group, indicating that systemic treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail induces little or no immune activation (Fig. S5 D and E).

Fig. S5.

Leukocyte counts during systemic treatment with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/i.v. injection). Monitoring of the number of white blood cells (WBC) (A), lymphocytes (B), and monocytes (C) in pre- and posttreatment with four i.v. injections of the 3-PPMO cocktail. Arrows indicate when injections of the 3-PPMO cocktail were administered. (D) Immunohistochemistry with the anti-dog CD3 antibody on skeletal and cardiac muscle sections in wild-type, nontreated, and treated dogs 2 wk after the final injection with 3-PPMOs. CD3-positive cells (indicative of T cells) and nuclei are shown in red and blue, respectively. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (E) The number of CD3-positive cells on immunostained muscle sections from wild-type, nontreated, and treated dogs. The positive cells were counted in 30 areas (10 areas/section) taken randomly at 200× magnification. DIA, diaphragm; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. A statistical test was performed with Student’s t test: **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 in nontreated dogs, respectively, compared with wild-type dogs. ns, no significant difference between nontreated and treated dogs.

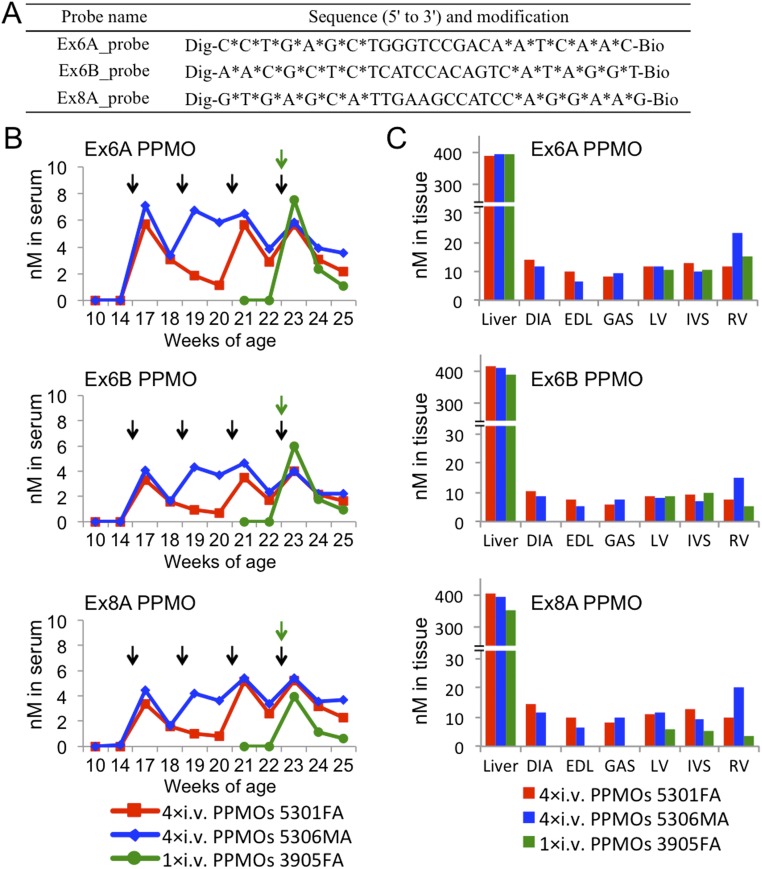

Concentrations of 3-PPMOs in Serum and Tissue Lysate from i.v.-Treated Dystrophic Dogs.

Concentrations of the three i.v.-injected PPMOs (Ex6A, Ex6B, or Ex8A PPMO, 4 mg/kg/PPMO/injection) in serum, liver, skeletal, and cardiac muscles were measured by ELISA using PPMO-specific DNA probes (Fig. S6A). Although no PPMOs were detected before the injection, the increased blood concentration of each PPMO was observed 24 h after every i.v. injection (except the second injection in dog 5301FA). A certain level of all 3-PPMOs was maintained throughout the treatment in i.v.-treated dogs regardless of injection frequency (Fig. S6B). After the final injection, the blood levels of individual PPMOs were uniformly and gradually reduced over time, with detectability persisting up to at least 2 wk later. We also found that all 3-PPMOs were detectable at comparable levels in skeletal and cardiac muscles collected 2 wk after the final injection (Fig. S6C), whereas no PPMOs were detected in muscles of nontreated dogs. The finding indicates that simultaneously injected different PPMOs can be evenly distributed to both skeletal and cardiac muscles regardless of muscle type and position (e.g., left and right ventricles and interventricular septum represented in Fig. S6C). PPMO accumulation in the liver was observed at much higher levels compared with the muscles in the three treated dogs.

Fig. S6.

Concentrations of i.v.-injected Ex6A, Ex6B, or Ex8A PPMO (4 mg/kg/injection) in serum and tissues of dystrophic dogs as detected by ELISA using the avidin–biotin affinity system. (A) Sequence and modification information of the DNA probes used to detect dog PPMOs. Dig, digoxigenin; Bio, biotin; an asterisk (*) indicates phosphorothioated DNA. (B) Concentrations of each PPMO in dog serum during the systemic treatment. Serum samples prepared pre- and postinjection (24 h, 1 wk, and 2 wk later) were subjected to the assay. The point immediately after an arrow indicates a serum sample collection 24 h after the injection. The concentration was calculated with a linear standard curve (R2 > 0.994) using a control Ex6A, Ex6B, or Ex8A PPMO. Black and green arrows indicate times of i.v. injection in consecutively treated dogs (5301FA and 5306MA) and in a dog injected once (3905FA), respectively. (C) PPMO concentrations expressed per milligram of protein lysate of liver, skeletal, and cardiac muscles harvested 2 wk after the final injection. DIA, diaphragm; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; GAS, gastrocnemius; IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Discussion

The incidence of cardiomyopathy in DMD patients is estimated to be ∼59% by 10 y of age (1), and almost 100% of patients exhibit some cardiac involvement by 18 y (30). Cardiac failure causes mortality in 12–20% of DMD patients (26, 31). As demonstrated in clinical trials and in many animal studies, PMO is a promising chemistry for exon-skipping therapy, especially in terms of its safety and sufficient effectiveness in skeletal muscles. However, systemic treatment using PMOs has induced barely detectable dystrophin protein levels in the myocardium of DMD animal models (10, 11, 32). The reasons for the observed variations in PMO efficacy between skeletal and cardiac muscles are largely unknown. To increase therapeutic potency in cardiac muscle, CPP-conjugated PMOs have been developed. Although PPMO efficacy varies depending on peptide components of PPMOs (18), systemic PPMO treatment has consistently induced high-efficiency production of truncated dystrophin protein in bodywide muscles of mdx mice, including the heart (17, 33). However, it remains to be determined if systemic injections with PPMOs could rescue expression of dystrophin protein in both skeletal and cardiac muscles of large animal models. In the present study, although low levels of rescued dystrophin protein were observed, systemic multiexon skipping using a 3-PPMO cocktail at 12 mg/kg restored dystrophin expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles of CXMDJ dogs in which dystrophin protein is normally undetectable. As assessed by Western blotting, the quantity of rescued dystrophin protein was not as high as expected in both skeletal and cardiac muscles of the CXMDJ dogs treated with systemic 3-PPMO injections, considering that previous studies in mdx mice showed dystrophin rescue to levels comparable to those of wild-type mice (17, 33). This variation may be due to the difficulty of skipping multiple exons (8) or to differences in experimental conditions, such as using a lower dose of 4 mg/kg for each PPMO (as in the present study) compared with a previous report of single exon skipping using a PPMO at 30 mg/kg administrated through i.v. injections in mice (17). Despite overall low levels of dystrophin rescue in CXMDJ dogs, the fact that we observed nearly equal dystrophin levels between the skeletal and cardiac muscles indicates that the peptide B modification can enhance the efficacy of SSOs in the myocardium of dystrophin-deficient dogs.

Another considerable concern in the present study is that no improvement of clinical grading scores and functions was found in skeletal muscles of CXMDJ dogs consecutively treated with the 3-PPMO cocktail at 12 mg/kg/injection. The failure of restoring skeletal muscle function may relate to the time of initiation of therapy. Unlike with DMD mouse models, dystrophic dogs exhibit progressive degeneration and clinical symptoms in skeletal muscles from the neonatal period (12). In this study, we began the treatment of affected dogs at 4 mo of age when the cardiac abnormalities became evident on ECG. The present finding suggests the need for starting PPMO treatment at younger ages to restore skeletal muscle functions in the dystrophic dog model. Also, it has been reported that rescue of more than 10% of normal dystrophin levels is required for functional recovery in skeletal muscle of a dystrophic mouse model (32). However, a recent clinical trial with an exon 51-skipping PMO antisense drug has had an encouraging result: very low to undetectable levels of rescued dystrophin protein in Western blotting analysis can help slow a decline in walking ability of DMD patients subjected to treatment with a single weekly i.v. injection over a span of 3 y (3). One implication from the clinical trial is that low expression levels of dystrophin (∼5% compared with healthy dogs) might have a potential for leading to some clinical benefit in skeletal muscles in long-term treatment.

DMD/BMD-associated cardiomyopathy includes various cardiac arrhythmias, as represented by ECG, implicating dysfunction of the cardiac conduction system. In fact, dystrophin-deficient Purkinje fibers have been reported to exhibit vacuole degeneration in patients with DMD (24, 31) and in CXMDJ dogs (22). We previously described overexpression of a dystrophin short isoform, Dp71, in the Purkinje fibers of CXMDJ dogs (22). However, the excess Dp71 expression does not compensate for a lack of the Dp427m (full-length) isoform in CXMDJ dogs. The rescue of full-length dystrophin (with exons 6–9 skipping) in Purkinje fibers could ameliorate or prevent cardiac arrhythmias in DMD patients. Our results support this hypothesis: the 3-PPMO cocktail administration ameliorated abnormally deep Q-waves and increased Q/R ratio in three CXMDJ dogs. These improvements appear to be associated with expression of the rescued full-length dystrophin protein and the amelioration of vacuole degeneration in Purkinje fibers.

In association with our observations of dystrophin rescue in PPMO-treated dog hearts, it has been reported that as little as <2% rescued dystrophin (compared with normal levels), as represented by Western blotting, improves cardiac function in a dystrophic mouse model (32). Also, unlike the working myocardium, expression of dystrophin-associated proteins, such as sarcoglycans and β-dystroglycan, is well maintained in the Purkinje fibers of CXMDJ dogs (22). Dystrophin-deficient heart, which is more mildly affected than skeletal muscles, might retain the potential to work normally if the cardiac conduction system can be improved with the rescue of full-length dystrophin. To examine this possibility, further studies are required with more optimized regimens for PPMO treatment in the dog model, such as dosages and routes of PPMO administration and injection frequencies. Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that dystrophin Dp427m plays an important role in maintaining the normal architecture and function of the cardiac Purkinje fibers.

As represented here, exon skipping with PPMOs can more effectively restore dystrophin expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles and ameliorate abnormalities of the cardiac conduction system in dystrophic animal models compared with unmodified morpholinos (10, 16, 34). However, higher toxicity is a major concern in the use of the PPMO chemistry (35). There was no obvious toxicity or immune response detected by blood tests, histological assessment, and antibody tests in mdx mice systemically injected with 30 mg/kg peptide B-conjugated PMO at 2-wk intervals for 3 mo (17) and at 1-mo intervals for 1 y (33). Tolerance to other arginine-rich CPPs has also been reported at up to 30 mg/kg in mdx mice with no apparent signs of toxicity (35, 36). Although the population of dogs used in this study is limited, our regimen involving a single i.v. injection and four i.v. injections at 2-wk intervals with the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg/injection, 4 mg/kg each) showed no obvious toxic effects in blood tests. An important finding in the present safety assessment is that residual PPMOs as detected by ELISA after the final injection did not induce adverse effects detectable in blood tests up to 2 wk later. We also found no apparent signs of immune activation as detected by leukocyte counts. However, a challenge to verify antibody production against CPPs remains to be resolved. Along with the effectiveness of PPMO-mediated multiple exon skipping, studies on the long-term safety of the PPMO chemistry need to be further pursued with various doses and frequencies. A current challenge in studies with PPMOs is the limitation of manufacturing sufficient PPMO amounts for large animal models as found in the present study using three different PPMOs. As PPMOs have high potential to treat DMD, particularly the heart, and to become a promising clinical drug candidate in exon skipping, this issue needs to be overcome before clinical trials begin.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the efficacy of multiexon skipping, using a 3-PPMO cocktail, in rescuing dystrophin protein expression in the cardiac muscles and bodywide skeletal muscles of a dystrophic dog model. In addition, we found that rescued dystrophin protein in cardiac Purkinje fibers could contribute to the improvement or prevention of conduction abnormalities in the dystrophic heart. The present preclinical data provide valuable information for translational research toward future human clinical trials involving exon-skipping therapy with PPMOs.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions of animal PPMOs and PMOs, injections of PPMOs and PMOs, clinical evaluation, locomotor activity assay, RT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, H&E staining, Western blotting, ECG, echo, blood tests, blood cell counting, and ELISA are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Experiment Committees of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry. All methods were performed according to the approved guidelines and under the supervision of veterinarians.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

Beagle-based CXMDJ and wild-type dogs were allowed ad libitum access to food and drinking water. A point mutation at the splice acceptor site of intron 6 in CXMDJ dogs was confirmed by genotyping, as previously described (10, 21). Affected CXMDJ dogs with heterozygous (in males) and homozygous mutations (in females) at 4–5 mo of age were used for the study. Four affected CXMDJ dogs were subjected to the PPMO treatment: three female dogs (ID nos. 3905FA, 3908FA, and 5301FA) with ECG abnormalities and a male dog (ID no. 5306MA) without abnormal ECG waves at the starting point of treatment. One male affected dog (ID no. 2001MA) was treated with an unmodified PMO cocktail to compare with the PPMO treatment in an ECG test in which the rescued dystrophin expression levels are available in our previous report (10). Samples from wild-type beagle dogs at 2–9 mo of age were prepared as a positive control. The dogs were humanely euthanized for collecting muscle samples; in the treated dogs, this was done 2 wk after the final injection.

PPMOs and PMOs.

The 3-PPMOs used to skip exons 6 and 8 were synthesized by Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. using the following antisense sequences: Ex6A, GTTGATTGTCGGACCCAGCTCAGG (24-mer, 63 to 86 in exon 6); Ex6B, ACCTATGACTGTGGATGAGAGCGTT (25-mer, 151 to +1 in exon 6); and Ex8A, CTTCCTGGATGGCTTCAATGCTCAC (25-mer, 78 to 102 in exon 8). The peptide B sequence used here was selected from our previous CPP screening (18). Control unmodified PMOs with the same sequence as the PPMOs were synthesized by Gene Tools as previously described (10).

Injections of PPMOs and PMOs.

PPMOs in a total volume of 1,000 μL of saline were injected locally into the left or right cranial tibialis muscle (equivalent to tibialis anterior muscles in humans) of dogs 3905FA and 3908FA at 12 wk of age (37). For the i.c. injection, a catheter was inserted into the femoral artery of dog 3908FA under general anesthesia by inhalation of isoflurane (Nacalai Tesque). A 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg each PPMO) was injected in 500-μL amounts into either the left or right coronary artery. Intravenous injections of the 3-PPMO cocktail (12 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg each) in 1,000 μL of saline were administrated through saphenous veins, once in dog 3905FA and four times at 2-wk intervals in dogs 5301FA and 5306MA (10). The dose of the cocktail PPMOs was determined according to our previous reports (16, 18). As a control, a 3-unmodified PMO cocktail at 120 mg/kg in total dose (40 mg/kg each PMO) was i.v.-injected once a week for five times in a CXMDJ dog (ID no. 2001MA).

Clinical Evaluation.

Clinical symptoms of consecutively i.v.-treated CXMDJ dogs 5301FA and 5306MA and three nontreated CXMDJ dogs were graded based on our previous method (10). In brief, the following items were evaluated on a 5-point scale before treatment and 2 wk after final administration of treatment: gait disturbance, hind-limb and temporal muscle atrophy, drooling, macroglossia, dysphagia, and playfulness. Muscle function was examined by measuring the time from left or right lateral recumbency to standing in wild-type, nontreated, and treated dogs 2 wk after the fourth PPMO injection.

Locomotor Activity Assay.

Physical activity levels of five affected dogs at 6 mo of age (three nontreated and PPMO-treated CXMDJ dogs 5301FA and 5306MA) were monitored using an infrared sensor system (Supermex, Muromachi Kikai), as previously described (38). One week after the final i.v. injection, frequency of locomotor activity was counted for 5 d with a 12 h light/dark cycle in a cage.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA extraction from frozen tissue sections was performed with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For intramuscularly treated samples, RT-PCR was performed using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions on 200 ng of DNase I-treated total RNA with 35 cycles of amplification. For muscle samples of dogs treated with an i.c. or i.v. injection, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then 40 PCR cycles were performed in a reaction mixture that was composed of Go Taq Green Master Mix (Promega), PCR primers and 8 μL of cDNA. In both one-step and two-step RT-PCRs, an exon 5 forward primer (CTGACTCTTGGTTTGATTTGGA) and exon 10 reverse primer (TGCTTCGGTCTCTGTCAATG) to the dystrophin gene were used. For a negative control, RNase-free water or RT reaction cocktail without an RT enzyme was used. Band intensity was quantified by ImageJ software (NIH), and exon-skipping efficiency (%) was calculated with the following formula: exons 6–9 skipped transcript intensity/(native + intermediate transcript combined intensity) × 100. Bands of the expected size for the exon-skipped transcript were extracted using a gel extraction kit (Promega). The sequencing reactions were performed with Big Dye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) and the same primers (10, 39).

Western Blotting.

Muscle protein from cryosections was extracted with lysis buffer composed of 75 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and proteinase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Protein lysates were loaded into 3–8% or 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gel for dystrophin or β-dystroglycan, respectively. Following SDS/PAGE, separated proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane by semidry blotting (Invitrogen) at 20 V for 70 or 30 min. Western blotting was performed with ab15277 dystrophin antibody against the C-terminal (1:5,000, Abcam) or NCL-DYS1 (1:200, Novocastra) following a blocking step with Amersham ECL Advance Blocking Reagent (GE Healthcare). β-Dystroglycan was detected with the NCL-b-DG antibody (1:300, Novocastra). Signals were detected with Amersham ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare). The band intensity was analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH). α-Actinin or desmin, detected with antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich and Abcam, respectively), or myosin heavy chain, visualized on a posttransferred gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue reagent, were used as loading controls.

Immunohistochemistry.

Cryosections at 7-μm thickness were prepared using a cryostat (Leica CM 1950, Leica). Sections were air-dried for at least 30 min at room temperature and then either fixed in acetone or left unfixed. Dystrophin signals were detected with mouse monoclonal NCL-DYS1 antibody against the rod domain of full-length dystrophin (1:100, Novocastra), as previously described (37). The sections were observed using a FLUOVIEW microscope (Olympus). The percentage of dystrophin-positive fibers was analyzed with more than 600 fibers in samples from intramuscularly treated dogs. To detect CD3-positive cells (indicative of T cells), anti-dog CD3 epsilon antibody (1:40, Abcam) was used to stain 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed muscle sections. The number of CD3-positive cells was counted in 30 randomly selected section areas at 200× magnification (10 areas/section at intervals of 100–200 μm).

H&E Staining.

Seven-micrometer cryosections were stained with Meyer’s H&E reagents (Electron Microscopy Sciences) (39). For centrally nucleated fiber counting, 200–1,200 fibers were counted in individual skeletal muscle sections. Vacuole area in cardiac Purkinje fibers was measured with grid meshes, and the relative values were expressed as a percentage of grid areas in accordance with Hally’s method (40).

ECG.

Because the leads aVR and aVL were not sensitive enough to detect abnormal ECG findings of CXMDJ dogs, leads I, II, III, and aVF were used for the measurement instead (ECG-922 electrocardiograph, Nihon Koden). To examine changes in Q-waves and the Q/R ratio, values from lead II were analyzed as previously described (21).

Echocardiography.

Left ventricular size, shape, and contractility were examined with echo (Hitachi Medical Corporation) with M-mode and 2D imaging as previously described (21).

Blood Tests and Blood Cell Counting.

Serum samples were collected 24 h, 1 wk, or 2 wk after the injection in systemically PPMO-treated CXMDJ dogs. Serum chemistry and blood cell counting were performed at a central laboratory (SRL Inc.).

ELISA.

ELISA using avidin–biotin interaction was performed to examine the concentrations of PPMOs in serum and tissues of dystrophic dogs treated with the i.v. injection according to the method of Burki et al. (41). Serum samples before treatment and in 24 h, 1 wk, and 2 wk after the PPMO injection were collected for the assay. Skeletal and cardiac muscle and liver lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Pooled lysates from the diaphragm or left ventricle of three nontreated dogs were used as negative controls. In brief, cDNA probes (Integrated DNA Technologies) that bind to the SSO sequences of dog Ex6A, Ex6B, and Ex8A PPMOs were prepared as follows: The 5′ and 3′ ends of the probes were labeled with digoxigenin and biotin, respectively. Nucleotides from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the probe DNA sequences were phosphorothioated to increase the stability of probe-target binding (Fig. S6A). Probe specificity was confirmed by a mismatch assay where hybridization to probes and PPMOs (e.g., an Ex6A probe was hybridized with a control Ex6B or Ex8A PPMO) that do not theoretically bind to the probe concerned was tested. Standard PPMOs, 10% serum samples, and tissue lysates (0.2 mg/mL and 0.02 mg/mL protein for muscle and liver samples, respectively) were pretreated with 2.5 mg/mL trypsin containing 10 mM CaCl at 37 °C overnight to digest the peptide portion of PPMOs. A linear standard curve (R2 > 0.994) was obtained in the range of 8–500 pM of a control Ex6A, Ex6B, or Ex8A PPMO. Following PPMO-probe hybridization, the avidin–biotin interaction of the hybridized cocktail probes was performed on Pierce NeutrAvidin Coated 96-Well Plates, Black (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Unhybridized probes were digested with micrococcal nuclease at 0.1 gel unit/μL (New England Biolabs). Then the hybridized probes were reacted with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (1:5,000, Roche Applied Science). Fluorescence signals from the PPMO-hybridized probes were detected at 444 nm excitation and 555 nm emission with AttoPhos AP Fluorescent Substrate (Promega) in a monochromator SpectraMax M3 plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Acknowledgments

We thank Masanori Kobayashi, Naoko Yugeta, Michihiro Imamura, Jing Hong Shin, Takashi Okada, Michiko Wada, Sachiko Ohshima, Satoru Masuda, Kazue Kinoshita, Manami Yoshida, Yuko Shimizu (National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry), Aleksander Touznik, Joshua Lee (University of Alberta), and Eric P. Hoffman (Binghamton University) for useful discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Research on Nervous and Mental Disorders (19A-7); Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants for Translation Research (H19-Translational Research-003 and H21-Clinical Research-015); Health Sciences Research Grants for Research on Psychiatry and Neurological Disease and Mental Health from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H18-kokoro-019) (to S.T.); NIH T32 training grant and fellowship; the Friends of Garrett Cumming Research HM Toupin Neurological Science Research; Muscular Dystrophy Canada; Jesse’s Journey Foundation; Women and Children’s Health Research Institute; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Canada Foundation for Innovation; Alberta Enterprise and Advanced Education; University of Alberta (T.Y.); and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad (Y.E.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: H.M.M., P.I., P.S., and R.K. were full-time employees of Sarepta Therapeutics, which owns patent rights to the peptide B sequence that was used in this study.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1613203114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Flanigan KM. Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Neurol Clin. 2014;32(3):671–688, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig M, et al. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987;50(3):509–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendell JR, et al. Eteplirsen Study Group and Telethon Foundation DMD Italian Network Longitudinal effect of eteplirsen versus historical control on ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(2):257–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.24555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echigoya Y, Mouly V, Garcia L, Yokota T, Duddy W. In silico screening based on predictive algorithms as a design tool for exon skipping oligonucleotides in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Béroud C, et al. Multiexon skipping leading to an artificial DMD protein lacking amino acids from exons 45 through 55 could rescue up to 63% of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(2):196–202. doi: 10.1002/humu.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura A, et al. Deletion of exons 3-9 encompassing a mutational hot spot in the DMD gene presents an asymptomatic phenotype, indicating a target region for multiexon skipping therapy. J Hum Genet. 2016;61(7):663–667. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aartsma-Rus A, et al. Theoretic applicability of antisense-mediated exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):293–299. doi: 10.1002/humu.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Echigoya Y, Yokota T. Skipping multiple exons of dystrophin transcripts using cocktail antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2014;24(1):57–68. doi: 10.1089/nat.2013.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoki Y, et al. Bodywide skipping of exons 45-55 in dystrophic mdx52 mice by systemic antisense delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(34):13763–13768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204638109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokota T, et al. Efficacy of systemic morpholino exon-skipping in Duchenne dystrophy dogs. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(6):667–676. doi: 10.1002/ana.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki Y, et al. In-frame dystrophin following exon 51-skipping improves muscle pathology and function in the exon 52-deficient mdx mouse. Mol Ther. 2010;18(11):1995–2005. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu X, Bao B, Echigoya Y, Yokota T. Dystrophin-deficient large animal models: Translational research and exon skipping. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(8):1314–1331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alter J, et al. Systemic delivery of morpholino oligonucleotide restores dystrophin expression bodywide and improves dystrophic pathology. Nat Med. 2006;12(2):175–177. doi: 10.1038/nm1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornegay JN, et al. Widespread muscle expression of an AAV9 human mini-dystrophin vector after intravenous injection in neonatal dystrophin-deficient dogs. Mol Ther. 2010;18(8):1501–1508. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue Y, et al. Safe and bodywide muscle transduction in young adult Duchenne muscular dystrophy dogs with adeno-associated virus. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(20):5880–5890. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jearawiriyapaisarn N, Moulton HM, Sazani P, Kole R, Willis MS. Long-term improvement in mdx cardiomyopathy after therapy with peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85(3):444–453. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu B, et al. Effective rescue of dystrophin improves cardiac function in dystrophin-deficient mice by a modified morpholino oligomer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):14814–14819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805676105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jearawiriyapaisarn N, et al. Sustained dystrophin expression induced by peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers in the muscles of mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16(9):1624–1629. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crisp A, et al. Diaphragm rescue alone prevents heart dysfunction in dystrophic mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(3):413–421. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willmann R, Possekel S, Dubach-Powell J, Meier T, Ruegg MA. Mammalian animal models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(4):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yugeta N, et al. Cardiac involvement in Beagle-based canine X-linked muscular dystrophy in Japan (CXMDJ): Electrocardiographic, echocardiographic, and morphologic studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urasawa N, et al. Selective vacuolar degeneration in dystrophin-deficient canine Purkinje fibers despite preservation of dystrophin-associated proteins with overexpression of Dp71. Circulation. 2008;117(19):2437–2448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanyal SK, Johnson WW. Cardiac conduction abnormalities in children with Duchenne’s progressive muscular dystrophy: Electrocardiographic features and morphologic correlates. Circulation. 1982;66(4):853–863. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.4.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura H, Hizawa K. Histopathological study of the conduction system of the heart in Duchenne progressive muscular dystrophy. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1982;32(6):1027–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1982.tb02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moise NS, et al. Duchenne’s cardiomyopathy in a canine model: Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(3):812–820. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology. 2003;99(1):1–19. doi: 10.1159/000068446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spurney CF. Cardiomyopathy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Current understanding and future directions. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):8–19. doi: 10.1002/mus.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crippa L, Ferro E, Melloni E, Brambilla P, Cavalletti E. Echocardiographic parameters and indices in the normal beagle dog. Lab Anim. 1992;26(3):190–195. doi: 10.1258/002367792780740512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun JP, Benard P, Burgat V, Rico AG. Gamma glutamyl transferase in domestic animals. Vet Res Commun. 1983;6(2):77–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02214900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nigro G, Comi LI, Politano L, Bain RJ. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Cardiol. 1990;26(3):271–277. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90082-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanagisawa A, et al. The prevalence and prognostic significance of arrhythmias in Duchenne type muscular dystrophy. Am Heart J. 1992;124(5):1244–1250. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90407-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu B, et al. One-year treatment of morpholino antisense oligomer improves skeletal and cardiac muscle functions in dystrophic mdx mice. Molecular Ther. 2011;19(3):576–583. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu B, et al. Long-term rescue of dystrophin expression and improvement in muscle pathology and function in dystrophic mdx mice by peptide-conjugated morpholino. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(2):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moulton HM, Moulton JD. Morpholinos and their peptide conjugates: Therapeutic promise and challenge for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798(12):2296–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amantana A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, stability and toxicity of a cell-penetrating peptide-morpholino oligomer conjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18(4):1325–1331. doi: 10.1021/bc070060v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Betts C, et al. Pip6-PMO, a new generation of peptide-oligonucleotide conjugates with improved cardiac exon skipping activity for DMD treatment. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2012;1:e38. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokota T, et al. Extensive and prolonged restoration of dystrophin expression with vivo-morpholino-mediated multiple exon skipping in dystrophic dogs. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22(5):306–315. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashita-Kinoh H, et al. Intra-amniotic rAAV-mediated microdystrophin gene transfer improves canine X-linked muscular dystrophy and may induce immune tolerance. Mol Ther. 2015;23(4):627–37. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Echigoya Y, et al. Long-term efficacy of systemic multiexon skipping targeting dystrophin exons 45-55 with a cocktail of vivo-morpholinos in mdx52 mice. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e225. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hally AD. A counting method for measuring the volumes of tissue components in microscopical sections. J Cell Sci. 1964;s3(105):503–517. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burki U, et al. Development and application of an ultrasensitive hybridization-based ELISA method for the determination of peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2015;25(5):275–284. doi: 10.1089/nat.2014.0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osborne BE, Leach GD. The beagle electrocardiogram. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1971;9(6):857–864. doi: 10.1016/0015-6264(71)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuzawa T, Nomura M, Unno T. Clinical pathology reference ranges of laboratory animals. Working Group II, Nonclinical Safety Evaluation Subcommittee of the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55(3):351–362. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolford ST, et al. Reference range data base for serum chemistry and hematology values in laboratory animals. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1986;18(2):161–188. doi: 10.1080/15287398609530859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aiello SE, Moses MA. 2016. The Merck Veterinary Manual, Online Edition (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ)