Abstract

Background:

Spiritual well-being (SWB) is an important quality-of-life dimension for cancer patients in the palliative phase. Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals to recognize the concept of SWB from the patient’s point of view. A deeper understanding of how patients experience and reflect upon these issues might influence patient care.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to explore SWB in colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the palliative phase.

Methods:

We used a qualitative method of in-depth interviews and a hermeneutic editing approach for the analyses and interpretations.

Results:

Twenty colorectal cancer patients in the palliative phase, aged 34 to 75 years, were included: 12 patients were receiving first-line chemotherapy, and 8 patients were receiving second-line chemotherapy. Through empirical analyses, we identified subthemes according to the SWB dimensions defined by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality-of-life group. Under the SWB dimension, (i) relationships with self and others, we identified the subthemes: (a) strategies for inner harmony and (b) sharing feelings with significant others. Under the dimension, (ii) existential issues, we identified the subtheme (c) coping with end-of-life thoughts. Under the dimension, (iii) specifically religious and/or spiritual beliefs and practices, we identified the subtheme (d) seeking faith as inner support.

Conclusion:

Knowledge about cancer patients’ use of different strategies to increase their SWB may help healthcare professionals to guide patients through this vulnerable phase.

Implication for Practice:

Healthcare professionals need sufficient courage and willingness to share their patients’ thoughts, beliefs, and grief to be able to guide patients toward improving their SWB.

KEY WORDS: Colorectal cancer, Qualitative research, Spiritual well-being

Atreatment goal for cancer patients in a noncurative situation is to enhance quality of life (QOL). Quality of life includes 4 dimensions, physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being (SWB), which are composed of subdimensions.1–4 The spiritual dimension is considered to be of particular importance to cancer patients in palliative phase.5–13 Spirituality can be defined as “the search for meaning in one’s life and the living of one’s life on the basis of the understanding of that meaning. It may involve (i) sustaining relationship with self and others, (ii) meaning beyond one’s self, (iii) meaning beyond immediate events, and (iv) explanations for events and/or experiences.”14(p860)

Spirituality can be explored from a substantive or a functional perspective.14 Spirituality from a substantive perspective explores the actual content or substance of a specific religious or spiritual belief. Spirituality from a functional perspective explores constructs such as spiritual health and SWB and focuses on how a person finds meaning and purpose in life and how a person’s behaviors and activities relate to these fundamental issues.14,15

Most previous studies include a combined substantive and functional perspective or a substantive perspective alone.14–16 In this study, we have chosen to take a functional perspective to investigate SWB because this is one aspect of spirituality where healthcare professionals can aid palliative cancer patients if necessary. Most studies on SWB have been undertaken in the United States. However, cultural differences may influence the results, and these findings may not necessarily be extrapolated to Scandinavian populations.14,17 The Scandinavian and Norwegian culture are characterized by collective and sociodemocratic values, and healthcare is free of charge. Traditionally, there has been a focus on community and shared responsibility. Until the last decades, fundamental values have been based on Christian traditions. An increasing secularization and privatization in the society in general and in religious understanding and faith specifically may have influenced peoples’ SWB.18 Moreover, studies have been conducted in heterogeneous patients groups with regard to cancer types and stages.10 As some cancer types are influenced by lifestyle and exogenous factors (eg, lung cancer, cervical cancer), this may impact the way some patients cope and evaluate/judge their illness and SWB.4

Several studies indicate that low SWB is associated with low QOL in cancer patients19,20 and that beneficial spiritual coping strategies may contribute to favorable adjustment to illness.21–23 However, the literature review by Thuné-Boyle et al24 reported inconsistencies in the beneficial effects of spiritual resources for illness adjustment. In some studies, religious coping could be detrimental or harmful in subsamples, whereas other demonstrated a beneficial effect on social support provided by the religious community and spiritual support from their relationship with God.24 In a metastudy of qualitative research, Edwards et al10 found that that spirituality was a broad term that could include or exclude religion. Furthermore, they found that relationships are a central part of spirituality, for example, relationships with self and others and relationship between spirituality and religion, which has been reported by others as well.24–27

The psychology of QOL includes the study of how patients adjust and cope with their illness and how patients tend to use strategies to optimize their QOL and the QOL subdimensions (eg, SWB).28 Response shift is 1 such strategy and is defined as a change in internal standards and values and a redefinition of what is important in the patient’s life, QOL, and SWB.28–30 Serious illness constitutes a new framework for the way those who are affected live and experience their lives. Using various strategies, serious ill patients tend to adjust their life goals, hopes, and the way they want to live and experience their new life in accordance with the new situation.28,30 The patients tend to shift their focus to other life domains or goals to optimize their QOL or QOL subdomains such as SWB,28 by emphasizing life domains or goals that bring comfort and that are achievable and meaningful to themselves.28,30 People with a positive personality are more likely to cope with changes caused by illness.28,31 Whether a person is able or unable to shift focus can also be influenced by the person’s social and structural context, which may promote or impede such changes; for example, affective and practical support from families and friends can promote changes that can help fulfill new goals.29

Purpose

Spiritual well-being is an important QOL dimension for patients in the palliative phase.5 Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals to recognize the concept of SWB from the patient’s point of view.10,27 A deeper understanding of how patients experience and reflect upon these issues might be important in their treatment and care. We aimed to explore SWB in colorectal cancer patients in the palliative phase undergoing chemotherapy.

Methods

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group has defined SWB according to 3 dimensions: (i) relationships with self and others, (ii) existential issues, and (iii) specific religious and/or spiritual beliefs and practices.14,15 The present data collection, analyses, and interpretation of results are based on the EORTC definition. The EORTC Quality of Life Group is a research organization that aims to develop reliable instruments for measuring the quality of life of cancer patients participating in international clinical trials.

To explore and understand the complexity and different facets of SWB, we chose a qualitative approach using in-depth interviews.32 We choose colorectal cancer because this is the second most common cancer diagnosed in women worldwide and the third most common cancer diagnosed in men,33 and it is likely that the diagnosis to a limited extent is associated with guilt and social stigma. Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were referred for noncurative chemotherapy at the Southern Hospital Trust in Norway were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 18 years or older, having metastatic colorectal cancer, referral to first- or second-line noncurative chemotherapy, an expected life expectancy of more than 6 months, and the ability to give written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of significant comorbidity that could compromise life expectancy, treatment with an investigational agent, or inability to understand or read Norwegian. Patients with conditions that the physician believed could affect the patient’s ability to understand or cope with the questions were not considered eligible. We aimed to include patients with a range of ages, educational levels, marital status, and other demographic and clinical characteristics within the study population.

We tried to avoid information overload when the patients were expected to be emotionally at their most vulnerable. Therefore, the patients were asked to participate when they attended for the second or third cycle of chemotherapy. The oncologists did not invite patients who were considered to be too emotionally vulnerable (4 patients) but otherwise informed the patient of the study and asked if he/she was willing to be contacted by the research interviewer (G.R.). The same researcher conducted all the interviews. G.R. did not know the patients before the interviews and did not treat the patients. One of the researchers (C.K.) was the oncologist of some of the patients but did not read the interviews; patients were informed about the oncologist’s role. Two to 4 days after the interview, G.R. contacted each patient by phone and asked whether the interview had influenced him/her negatively in any way. Data were collected from October 2012 to October 2013. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (REK South-East 2011/2464). Written informed consent was obtained. All included patients gave permission to record the interviews, and none withdrew during or after the interviews. Voluntariness and confidentiality were assured during the collection, handling, and reporting of data.34,35

Data Collection

Before we started the study, we performed 3 pilot interviews with cancer patients to test the interview guide, and we made minor changes to the guide. The pilot interviews are not included in the study. We performed semistructured in-depth interviews lasting from 50 to 108 minutes using a semistructured interview guide to ensure that we included the issues under study.32 We asked the patients questions such as “How do you experience your life after you became ill?” “What is important for you?” “How is your relationship with your nearest family and friends?” and thoughts about God or a greater power. After the 11th interview, we did some preliminary analyses and made minor changes to the interview guide. We approached patients based on their availability, and to achieve variation of the sample, data saturation and Polit’s36 recommendation of sample size in qualitative studies. Nineteen interviews took place in the hospital and one in the patient’s home. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by G.R., a researcher who has previously worked in a surgical department with colorectal cancer patients.

Analysis

We used the following steps in the analyses: (i) reading all of the text to obtain an overall impression and bracketing preconceptions, (ii) identifying units of meaning that represent different aspects of the patients’ experiences and coding these, (iii) condensing and abstracting the meaning within each of the coded groups, and (iv) summarizing the contents of each coded group to generalize descriptions and concepts reflecting the most important experiences reported by the patients.32(p151) When organizing the data, we used Crabtree and Miller’s32(p22) editing organizing style. Furthermore, we used a hermeneutic editing approach to the analyses and interpretations, which implies that the participant’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences are central and that the researcher’s prestudy understanding is drawn into the interpretation of the findings.32(p145) The findings were further analyzed in light of the theory of the psychology of QOL, with a special focus on response shift and the SWB dimension.4,28,29 To validate the findings, all study team members participated in discussions about the empirical analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Findings

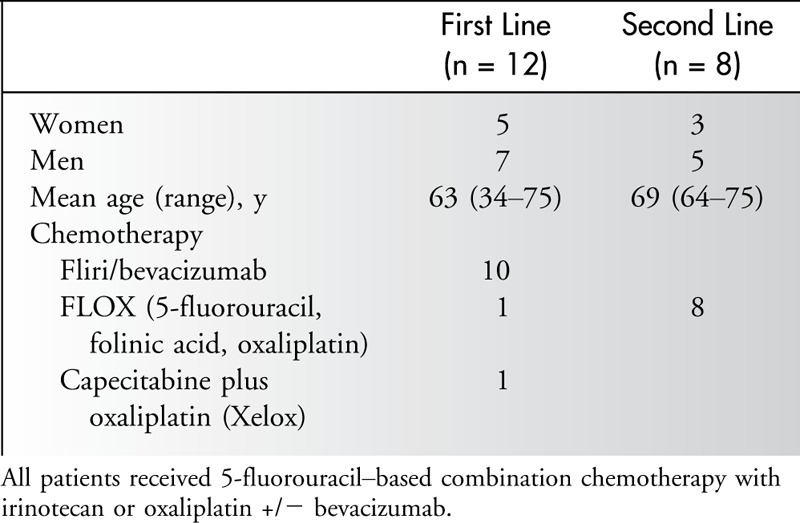

All 20 colorectal cancer patients who were invited to participate in the study accepted the invitation. Participants were 34 to 75 years of age; 12 were receiving first-line chemotherapy (5 women and 7 men), and 8 were receiving second-line chemotherapy (3 women and 5 men). All participants received combination chemotherapy (Table) and had few physical symptoms related to their disease, except that they felt more tired than they previously felt.

Table.

Characteristics of the Colorectal Patients Receiving Noncurative Chemotherapy

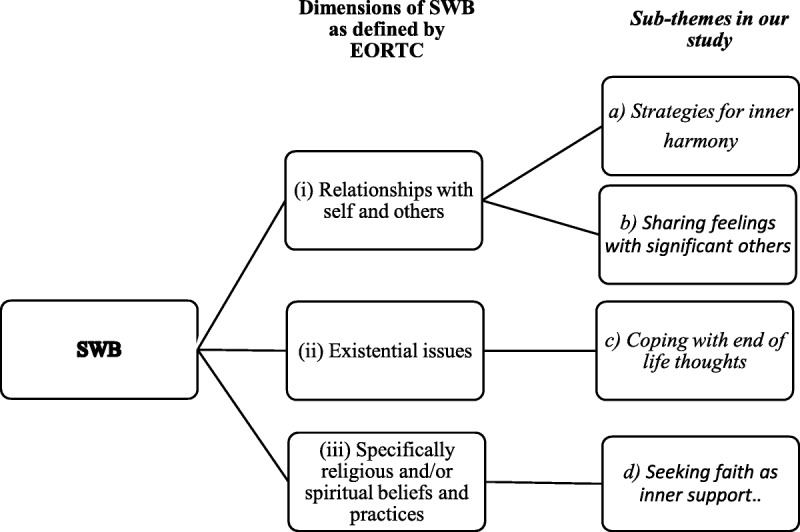

Through empirical analyses, we identified subthemes according to the SWB dimensions identified by the EORTC Quality of Life Group (Figure).14 Under the SWB dimension (i) relationships with self and others, we identified the subthemes (a) strategies for inner harmony and (b) sharing feelings with significant others; under (ii) existential issues, we identified the subtheme (c) coping with end-of-life thoughts; and under (iii) specifically religious and/or spiritual beliefs and practices, we identified the subtheme (d) seeking faith as inner support. Although the subthemes were organized according to the SWB dimensions identified by the EORTC,14 there was some overlapping among the subthemes and dimensions. We observed no obvious differences in SWB between patients receiving first- and second-line chemotherapy during the interviews and analyses of the data.

Figure.

The observed subthemes in this study related to the SWB dimensions defined by EORTC Quality of Life Group in colorectal cancer patients in the palliative phase.

Strategies for Inner Harmony

During the process of seeking inner harmony, most participants emphasized the importance of recognizing the painful thoughts about and reality of their incurable disease. Their feelings fluctuated between psychologically painful issues and positive feelings, and it was important to find a balance between negative feelings such as grief and sadness with positive feelings.

I have to allow myself to be sad, but I can’t be there all the time. So when I receive a sad message, I put the alarm clock on for 5, 10, 15 minutes or half an hour. I decide, “Okay, I can cry that long and then take a shower and go for a walk.” (p18, woman, 34 years)

Long-term goals were adjusted, and short-term goals were emphasized. More or less intentionally, most participants tended to focus on achievable and positive goals. The participants observed that small, positive everyday experiences and events were valuable to them. Details that previously had been annoying or were a focus were no longer important. Their lives had become simpler in a way, and several of the participants said they felt surprisingly well and managed to live a good life despite their illness. It was important to them just to exist, relax, and appreciate and take care of the simple issues.

I have turned out to be better to live in the moment. It is an eye opener that we are always in a hurry and never have time for anything. So, now I have time, and my condition has affected how I live my life. I don’t hurry and stress so much anymore. I am able to just calm down. (p4, women, 54 years)

In contrast to the participants who felt calm despite the fact that their cancer was incurable, some participants revealed that their feelings were more ambiguous; they focused more on painful thoughts than positive issues and felt restless. This approach influenced the participants’ search for inner harmony by reducing their ability to adjust to their new situation.

Sharing Feelings With Significant Others

Some participants spoke more openly about their inner thoughts after they became ill. These participants felt that this change in communication and relational openness was good and had enriched their lives.

My life is better. It sounds strange, but it actually is. I can talk with my family about thoughts and feelings. Previously, I knew it should be like that, but we didn’t do it. Men should be tough. I can do that now. Now I am not afraid to cry either. (p14, man, 58 years)

The quality of relationships between the participants and their families and friends became more prominent. Those with good relationships observed that their relationships became even better and closer. By contrast, participants with a complicated family relationship did not experience improvement after they became ill and were unable to use this relationship to increase their SWB. These participants felt alone and only to a limited extent shared their thoughts or sought help and comfort from their spouse and significant others.

Yes, you are alone. In the end you are alone. So, I don’t feel that this is anything special. (p7, man 61 years)

Some participants made a conscious choice not to tell the family the entire truth about their disease. This strategy was used to spare their closest family members, usually because they looked upon themselves as being the strongest member in the relationship and therefore judged this as the best way of handling the situation. These participants noted that this protective strategy when coping with problems and challenges was apparent before they became ill and was a part of their personality traits.

Coping With End-of-Life Thoughts

Our findings revealed facets of the participants’ thoughts and feelings about the end of life and how it influenced their existential issues. Most were not afraid of death and were aware of their incurable disease. On the other hand, some thought they would live for years despite the poor prognosis and did not consider death to be near. Some found the thought of a long and painful process leading to death difficult. Some suppressed these by doing practical things, whereas others sought quietness in nature.

I am worried about how I am going to die, and I don’t know how I will handle it psychologically when the time comes. (p6, man, 64 years)

Seeking Faith as Inner Support

Participants with a faith in God or a greater power had always used their faith to increase their resiliency and to cope when they felt troubled and continued to do so after they became ill. The relationship was personal, and they used this relationship in their own way.

With regard to my relationship with God and my faith, I decide myself and have always done that. In a way, I have my own faith. (p4, woman, 58 years)

These participants did not place their destiny only in God’s hand, although some described their faith as fundamental in their lives and something tangible. The strength and power provided by God or a greater power were considered to be a supplement to what medical treatment and care could provide. God or a greater power was used as a collaborator and supporter.

The time when I am going to die is in Dr X.’s and God’s hands; the medical treatment, Dr X. can provide. (p17, woman 71 years)

Participants without a faith handled their thoughts and feelings about death without experiencing support from a greater power. Their death was considered as the end—like switching off the light—and these patients were confident about this thought. We did not identify a correlation between being without a faith in God or a greater power and difficult or frightening thoughts about death and other dimensions included in SWB. By contrast, participants with a faith in God or a greater power who believed in a life after death found their faith to be a consolation, something fine and peaceful. Participants did not have an image of heaven in a strictly Christian biblical way. One expressed her thoughts about heaven as follows:

I am a kind of wondering, will it be like this or that. But I am confident that there is something—something that includes no harm, something good and peaceful, maybe a long, long sleep. I don’t know, that is up to God. I don’t think of any streets of gold or things like that. I think there is something there; it is love and no evil things. At least it is something to look forward to, not to dread. (p17, woman, 71 years)

The substance of the belief system did not change, and no participants changed from being a nonbeliever to a believer or vice versa around after they became ill. However, the function of a belief system became more prominent in some—they needed it more. Participants without a faith were confident about their lack of faith, even though a few thought that their illness would have been easier to cope with if they could look forward to a life after death. Controversial questions, such as the existence of hell, were not mentioned. With regard to faith, the details were trivial, and the complexity minimized.

My faith has perhaps become more basic, more childlike. I feel too tired for all these theological debates, all the dogma. I need it to be very basic. (p17, woman, 71 years)

Participants did not expect healthcare professionals to initiate conversation about existential issues including beliefs, although they would have welcomed it if their caregivers had initiated such conversations. Some emphasized the importance of not being intrusive and wished that healthcare professionals could acknowledge the participant’s existing faith and listen.

It is important not to be intrusive but to listen to the patient. (p.17, woman, 71 years)

A trusting relationship between the participant and healthcare professional was emphasized as an important prerequisite for a conversation about existential issues. The healthcare professional’s personality was also considered important, whereas the professional background (ie, whether it was a nurse or physician who initiated the conversation) was irrelevant.

Discussion

Our findings reveal how colorectal cancer patients in the early palliative phase adjust and cope with their illness in terms of their SWB: their relationships with themselves and others, existential issues, and specifically religious and/or spiritual beliefs and practices. To deepen our understanding of how a patient’s SWB might be influenced by having incurable cancer, we discuss our findings in light of the theory of the psychology of QOL. We describe how the patients use cognitive, affective, and behavioral strategies to adjust to changes in life to help optimize their QOL and QOL subdimensions such as SWB.17,28 We also discuss the implications of our findings for healthcare professionals.

Strategies for Inner Harmony

In our study, it seemed that most of the participants underwent a response shift as part of their search for inner harmony, although some seemed to experience problems undergoing a response shift and dwelt on painful and depressing thoughts and feelings. Factors that might prevent a response shift are having a negative or depressed personality and limited experience in managing resistance and reappraisal.28,30,31 Contextual factors such as fragile relationships with family members and friends30 may also limit the process. During the process of adapting to their change in health, the participants seemed to fluctuate between a previous goal of achieving a good life and their accommodation in trying to achieve other meaningful goals. This alternating process is, to a limited extent, described by the response shift theory.30,37–39 Our clinical experience suggests that such fluctuation is a normal and necessary part of the process of reconceptualization.

Sharing Feelings With Significant Others and Coping With End-of-Life Thoughts

Satisfaction with life domains related to intrinsic goals is often more important to a person’s well-being than fulfillment of extrinsic goals or factors.28 A closer relationship with families and friends might be considered as an intrinsic factor that the participants in the present study intentionally emphasized to increase their SWB after they became ill. Increasing the importance of 1 positive domain that contributes to SWB may compensate for a negative life domain and thereby balance the effects of the domains that contribute to SWB.28 The positive influence of social support and closeness with family and friends in terms of coping, adjustment, and resilience to stress seen in our study has been observed in other studies.40–42 Patients without close relationships or patients with complicated relationships with their family and friends may have a reduced ability to improve the relationship domain and its contribution to a higher SWB and may therefore be in a more vulnerable position.

Facing death and discussing it openly might reduce the feelings of distress and pain.41,43 On the other hand, anxieties about the unspeakable can generate a feeling of fear.43 Clarifying and sharing important information about the prognosis and future expectations are likely to facilitate good relationships, whereas ambiguity or secrecy can block understanding, closeness, and coping.43 This may have been the case for the participants who protected their family from full knowledge about their condition and for the participants who were fearful of the psychological aspects of managing death. The participants who withheld information from their family present a challenge to the theory of the psychology of QOL and favorable illness adjustment and coping. By withholding important information, they might limit their ability to manage the situation and to receive affective and behavioral support from significant others. Furthermore, such participants did not use their ability to increase the importance of the SWB dimension “relationship with others” to increase their SWB.28,44

Seeking Faith as Inner Support

Previous studies have indicated that spiritual identity and religious practice seem to affect illness adjustment positively by providing social and emotional support through prayer and by being a member of a religious community.4,45–47 The belief that God controls the cancer and thereby provides an entity that is in charge seems to be prominent.4,30,45,48 However, the participants in our study considered God as a collaborator more than an almighty God. Thus, the function of faith in God for illness adjustment seen in previous studies45,49 differs from our findings. Our findings seem to support the findings of, for example, recent research on the religious sociology of southern Norway, which have described the changes in the way people perceive God.18 Whereas the earlier modern images depicted God as an almighty judge, the postmodern picture tends to be both individualized and privatized. God is depicted more as a friend than as a universal and almighty God. These findings can be considered as a cultural phenomenon. In societies such as the United States where not all patients have the opportunity to choose the best cancer treatment and care because of their financial situation, one way of coping is to believe that God controls the cancer and thereby provides an entity that is in charge. This has been shown by Sterba et al50 in their qualitative study of African American breast cancer patients, Holt et al46 in their study of African Americans, and Koffman et al45 in their study of black Caribbean and white British patients with advanced-stage cancer. Because of the way of organizing the healthcare in Norway and Scandinavia, such a coping strategy might to a lesser extent be prominent. The importance of the meaning/peace factor of SWB for QOL is also shown by Bai and Lazenby17 in their systematic review of quantitative research in patients with cancer.

Implication for Healthcare Professionals

Our participants did not expect healthcare professionals to initiate a conversation about existential issues and other SWB issues, although they said that they would have appreciated such action by the healthcare professional. They preferred that healthcare professionals avoided being intrusive yet listen to them and acknowledge their faith. They emphasized the importance of a trusting relationship with healthcare professionals and that the healthcare professional’s personality was important to any conversation about existential issues. In the clinical context, this requires time for the patient or healthcare professional to raise SWB issues. An active approach to a patient’s SWB requires that the healthcare professional is willing to share the patient’s thoughts, suffering, and grief. Such a role may be demanding, but may also be enriching for healthcare professionals.

For healthcare professionals, an active approach may include identifying vulnerable patients who do not have the opportunity or ability to improve their SWB and QOL in general and to then assist and guide them. For patients who struggle with a response shift, the healthcare professional can suggest techniques to optimize their SWB. For patients who withhold information from the family, the healthcare professional can act as a facilitator by arranging meetings with the patient and his/her family. By participating in such meetings, the healthcare professional may be able to speak openly about the illness and, in doing so, encourage the patient and family to do the same. For patients with poor or complicated relationships with family and significant others, healthcare professionals can openly address issues such as fear, hope, or specific medical issues with the patient in the presence of a relative and thereby facilitate a communication about fear and hope between the patient and his/her relatives. Finally, more active and tailored care may help patients improve their coping strategies and resiliency to illness and their SWB.

Methodological Considerations

This was a qualitative study, and as such, it has methodological strengths and limitations. The strengths of the study are that the participants shared their thoughts and feelings about SWB and provided in-depth knowledge about the topic. The study included both female and male patients with 1 type of cancer who were in the palliative phase, which may have meant that knowledge tailored to this group was easier to obtain. Patients with colorectal cancer might to a lesser extend be influenced by shame and guilt because of their former way of living than other cancer groups, which further might influence their SWB. Within the group, there was a variation in sociodemographic factors such as age, marital status, and educational level. We included participants with good and close relationships with family and friends and those with complicated relationships. We also included participants with and without a faith in God or a greater power. This implies that there was diversity with regard to the central dimensions that SWB comprises, which was the main focus of this study. The authors are a nurse, oncologist, and a gynecologist treating cancer patients and theologian, all of whom have extensive clinical experience. Finally, all team members participated in both the analyses and preparation of the article. A limitation of the study is that the patients were expected to have a life expectancy of more than 6 months, which implies that patients closer to death were not included. Furthermore, the patients who were considered to be most vulnerable were not included in the study. We might have had additional finding if these (4) patients had been included in the study. Although our findings may not be generalizable to different groups, they may be transferable to similar cultural contexts, for example, in Norway and Scandinavia.

Conclusion

The findings in the present study provide a deeper understanding of how colorectal cancer patients in the palliative phase adjust to and cope with their illness in terms of their SWB. In the context of the participants’ relationships with themselves, they seemed to change their goals to other reachable goals in an attempt to increase their SWB. In terms of their relationships with others and God or a greater power, they seemed to emphasize relationships that were important before they became more ill. Our findings might be seen in light of the secularization and privatization in society in general and in religious understanding and faith specifically, which further might change the way healthcare professionals approach the patients’ SWB. Healthcare professionals who are aware of the mechanisms contributing to SWB in palliative cancer patients may be able to help guide patients in optimizing their SWB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank the patients who helped us in designing the study: Kari Gro Nuland Kristoffersen† and Oddvar Olsen†. We also want to thank all the patients who participated in the study.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(6):523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.What quality of life? The WHOQOL Group. World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment. World Health Forum. 1996;17(4):354–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin HR, Bauer-Wu SM. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(1):69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobb M, Puchalski CM, Rumbold BD. Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaasa S, Loge JH. Quality of life in palliative care: principles and practice. Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conroy T, Bleiberg H, Glimelius B. Quality of life in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: what has been learnt? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(3):287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saeteren B, Lindström UÅ, Nåden D. Latching onto life: living in the area of tension between the possibility of life and the necessity of death. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(5–6):811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, Muller M, Schornagel JH. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(18):3295–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of spirituality in advanced cancer patients: a randomized control study. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(13):1779–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med. 2010;24(8):753–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkelman WD, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The relationship of spiritual concerns to the quality of life of advanced cancer patients: preliminary findings. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(9):1022–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimmel PL, Emont SL, Newmann JM, Danko H, Moss AH. ESRD patient quality of life: symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(4):713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vivat B; Members of the Quality of Life Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Measures of spiritual issues for palliative care patients: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2008;22(7):859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivat B, Young T, Efficace F; EORTC Quality of Life Group. Cross-cultural development of the EORTC QLQ-SWB36: a stand-alone measure of spiritual wellbeing for palliative care patients with cancer. Palliat Med. 2013;27(5):457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asgeirsdottir GH, Sigurbjörnsson E, Traustadottir R, Sigurdardottir V, Gunnarsdottir S, Kelly E. “To cherish each day as it comes”: a qualitative study of spirituality among persons receiving palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(5):1445–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai M, Lazenby M. A systematic review of associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life at the scale and factor levels in studies among patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(3):286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Repstad P. A softer God and a more positive anthropology: changes in a religiously strict region in Norway. Religion. 2009;39(2):126–131. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(2):81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krupski TL, Kwan L, Fink A, Sonn GA, Maliski S, Litwin MS. Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(2):121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gall TL. Relationship with God and the quality of life of prostate cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(8):1357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanez B, Edmondson D, Stanton AL, et al. Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1140–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thuné-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, Newman SP. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(1):151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams AL. Perspectives on spirituality at the end of life: a meta-summary. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4(4):407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blinderman CD, Cherny NI. Existential issues do not necessarily result in existential suffering: lessons from cancer patients in Israel. Palliat Med. 2005;19(5):371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henoch I, Danielson E. Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sirgy MJ. The Psychology of Quality of Life. Dordrecht; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz CE, Bode R, Repucci N, Becker J, Sprangers MA, Fayers PM. The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: a meta-analysis of response shift. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(9):1533–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mols F, Holterhues C, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse LV. Personality is associated with health status and impact of cancer among melanoma survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(3):573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. ed New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.WMA Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/. Accessed April 12, 2016. [PubMed]

- 36.Polit DF. Essentials of Nursing Research: Methods, Appraisal, and Utilization. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz CE, Andresen EM, Nosek MA, Krahn GL; RRTC Expert Panel on Health Status Measurement. Response shift theory: important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClimans L, Bickenbach J, Westerman M, Carlson L, Wasserman D, Schwartz C. Philosophical perspectives on response shift. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz CE, Quaranto BR, Rapkin BD, Healy BC, Vollmer T, Sprangers MA. Fluctuations in appraisal over time in the context of stable versus non-stable health. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiegel D. Mind matters in cancer survival. JAMA. 2011;305(5):502–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh F. Family resilience: a framework for clinical practice. Fam Process. 2003;42(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson IJ. “I know he controls cancer”: the meanings of religion among black Caribbean and white British patients with advanced cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holt CL, Caplan L, Schulz E, et al. Role of religion in cancer coping among African Americans: a qualitative examination. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(2):248–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(5):581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rapkin BD, Schwartz CE. Toward a theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42(spec no 3):24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sterba KR, Burris JL, Heiney SP, Ruppel MB, Ford ME, Zapka J. “We both just trusted and leaned on the Lord”: a qualitative study of religiousness and spirituality among African American breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(7):1909–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]