Abstract

Background and Aim:

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing structural colonic diseases. It is safe and effective both for diagnosis and therapeutic interventions. This study was carried out to evaluate the pattern of indications and spectrum of colonic disease at a tertiary healthcare facility in Southwest Nigeria.

Patients and Methods:

All consenting patients who were referred for colonoscopy were recruited into the study. A proforma was used to record information such as biodata of the patients, indications for the procedure, and the findings at colonoscopy.

Results:

There were 250 patients, comprising 130 (52.0%) males and 120 (48.0%) females, with a male to female ratio of 1.1:1. The mean age of the patients was 57.9 ± 14.2 years with a range of 15–90 years. The most common indication for colonoscopy was hematochezia 85 (34.0%), others were abdominal pain 46 (18.4%), suspected colonic cancer 27 (10.8%), constipation 27 (10.8%), and chronic diarrhea 22 (8.8%). Sixty-five (26%) patients had normal colonoscopy while various abnormalities were detected in 185 (74%) patients. The most common abnormalities were colonic polyps (23.2%), hemorrhoids (20.8%), diverticulosis (14.8%), colorectal tumor (12.1%), and colitis (4.0%).

Conclusion:

Colonoscopy is an effective means of diagnosing colonic diseases and that the diagnostic yield could be high if the indication were appropriate. The most common indication in our practice was hematochezia, and the most frequent diagnosis was colonic polyps.

Keywords: Colonic polyps, colonoscopy, hematochezia, Southwest Nigeria, Polypes du côlon, coloscopie, rectorragies, Southwest Nigeria

Résumé

Contexte et Objectif:

coloscopie est considérée comme l’étalon-or pour le diagnostic des maladies colique structurelles. C’est sûr et efficace à la fois pour le diagnostic et les interventions thérapeutiques. Cette étude a été réalisée pour évaluer le motif des indications et spectre de la maladie du côlon à un établissement de santé tertiaire au sud-ouest du Nigeria.

Patients et Méthodes:

Tous les patients consentants qui ont été référés pour la coloscopie ont été recrutés dans l’étude. Un formulaire a été utilisé pour enregistrer des informations telles que les données biographiques des patients, des indications relatives à la procédure, et conclusions à la coloscopie.

Résultats:

Il y avait 250 patients, comprenant 130 (52,0%) hommes et 120 (48,0%) des femmes, avec un mâle à femelle rapport de 1,1: 1. L’âge moyen des patients était de 57,9 ± 14,2 années avec une gamme de 15-90 ans. Le plus commun indication pour la coloscopie était hematochezia 85 (34,0%), d’autres étaient des douleurs abdominales 46 (18,4%), soupçonné colique le cancer 27 (10,8%), la constipation 27 (10,8%) et de la diarrhée chronique 22 (8,8%). Soixante-cinq (26%) patients avaient normale coloscopie tandis que diverses anomalies ont été détectées dans 185 (74%) patients. Les anomalies les plus fréquentes étaient polypes du côlon (23,2%), les hémorroïdes (20,8%), la diverticulose (14,8%), colorectal tumeur (12,1%), et la colite (4,0%).

Conclusion:

La coloscopie est un moyen efficace de diagnostic des maladies du côlon et que le rendement diagnostique pouvait être élevé si l’indication était appropriée. L’indication la plus commune dans notre pratique était rectorragies, et la plus fréquente était le diagnostic des polypes du côlon.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing colonic diseases.[1] It gives an excellent view of the mucosa of the entire colon as well as that of the terminal ileum and has made the diagnosis of colonic benign and malignant tumors easy. In trained hands, colonoscopy is safe and effective not only for diagnosis but also for therapeutic interventions in the gastrointestinal system.[2] In recent years, indications for colonoscopy and its use in gastroenterology have increased, due to its recommendation as the preferred strategy for early detection of colorectal carcinoma by the American College of Gastroenterology in the year 2000.[3]

In the USA, a large national database showed that the most common indications for colonoscopy were surveillance of prior neoplasia, evaluation of hematochezia, and positive fecal occult blood test.[4] However, in a large multicenter study in Europe, the main indications were surveillance after polypectomy or colorectal cancer resection, hematochezia, uncomplicated abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, and iron deficiency anemia.[5]

Although there are reports on colonoscopy practice in Nigeria,[6,7,8] but this procedure is still not widely available compared to what obtains in the developed countries, due to lack of facilities and trained experts.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the pattern of indications and the spectrum of colonic pathologies at a tertiary health care facility in Southwest Nigeria.

Patients and Methods

This was a prospective study at the endoscopy unit of the University College Hospital, Ibadan. All consenting patients who were referred for colonoscopy were recruited into the study. A proforma was used to record information such as biodata of the patients, indications for the procedure, and the findings at colonoscopy.

All the patients underwent bowel preparation which commenced about 3 days before the procedure. The bowel preparation consisted of liquid diet, 10–30 mg of bisacodyl tablets in the morning, bisacodyl suppository nocte, as well as 1 L of normal saline taken orally twice daily, all for 3 days before the procedure. The bowel preparation was graded as good, satisfactory, or poor. Those who had poor bowel preparation were asked to take about a liter of normal saline orally, and the procedure was repeated after about 1–2 h on the same day.

Premedications were given to all the patients, which consisted of intravenous midazolam 2.5–5 mg and pentazocine 15–30 mg in titrated doses. Before, during, and after the procedure, patients’ vital signs were monitored using multiparameter monitor (Marathon Z, Healthcare Equipment & Supplies Co. Ltd. UK).

Digital rectal examination was carried out on all the patients before the insertion of the colonoscope. Colonoscopy was thereafter performed using Olympus Exera III Videocolonoscope (CF HQ190L) with the patient in the left lateral position. Supine posture and abdominal pressure were applied where necessary.

After the procedure, all the patients were observed for about 2 h before being discharged home with an assistant. They were also counseled with respect to resumption of oral intake and to report any observed complication immediately.

Results

A total of 250 patients comprised 130 (52.0%) males and 120 (48.0%) females with a male to female ratio of 1.1:1. The mean age of the patients was 57.9 ± 14.2 years with a range of 15–90 years. Analysis of the age groups showed that majority (49.2%) of the patients was between 50 and 69 years of age [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age group distribution of the patients

| Age group (years) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| <30 | 7 (2.8) |

| 30-39 | 20 (8.0) |

| 40-49 | 42 (16.8) |

| 50-59 | 61 (24.4) |

| 60-69 | 62 (24.8) |

| ≥70 | 58 (23.2) |

| Total | 250 (100) |

The mean age of the male patients (56.9 ± 14.1 years) was slightly lower than that of the females (58.9 ± 14.5 years).

The most common indication was hematochezia 85 (34.0%) followed by abdominal pain 46 (18.4%), suspected colonic cancer 27 (10.8%), constipation 27 (10.8%), and chronic diarrhea 22 (8.8%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Spectrum of indications for colonoscopy

| Indication | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Hematochezia | 85 (34.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 46 (18.4) |

| Suspected colonic tumur | 27 (10.8) |

| Constipation | 27 (10.8) |

| Chronic diarrhea | 22 (8.8) |

| Altered bowel habit | 9 (3.6) |

| Screening colonoscopy | 8 (3.2) |

| Dyspepsia | 6 (2.4) |

| Weight loss of unknown etiology | 5 (2.0) |

| Anemia of unknown etiology | 4 (1.6) |

| Positive fecal occult blood | 3 (1.2) |

| Raised carcinoembryonic antigen | 3 (1.2) |

| Melena | 2 (0.8) |

| Passage of mucoid stool | 2 (0.8) |

| Suspected ileal lesion on abdominal computed tomography | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 250 (100) |

The results also showed that 65 (76.5%) of those with hematochezia were 50 years of age and above, 18 (66.6%) of those with constipation and 14 (63.7%) of those with chronic diarrhea were 60 years of age and above.

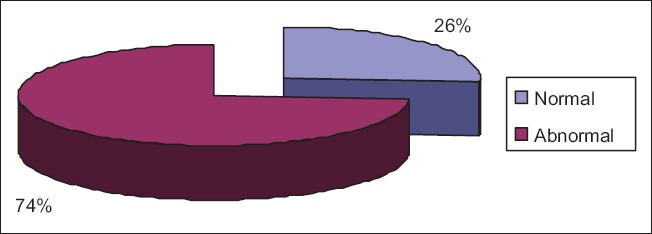

Colonoscopic findings showed that 65 (26%) of the patients had normal colonoscopy while various abnormalities were detected in 185 (74%) patients [Figure 1]. The most common abnormalities were colonic polyps (23.2%), hemorrhoids (20.8%), diverticulosis (14.8%), colorectal tumor (12.1%), and colitis (4.0%) [Table 3].

Figure 1.

Diagnostic yield of colonoscopy

Table 3.

Spectrum of colonoscopic diagnosis

| Diagnosis | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Colonic polyps | 68 (22.9) |

| Hemorrhoids | 62 (20.9) |

| Diverticulosis | 44 (14.8) |

| Colorectal tumor | 36 (12.1) |

| Colitis | 12 (4.0) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 4 (1.3) |

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (0.3) |

| Tuberculous ileitis | 1 (0.3) |

| Portal hypertensive colopathy | 1 (0.3) |

| Ileocecal tuberculosis | 1 (0.3) |

| Colonic Kaposis sarcoma | 1 (0.3) |

| Colonic schistosomiasis | 1 (0.3) |

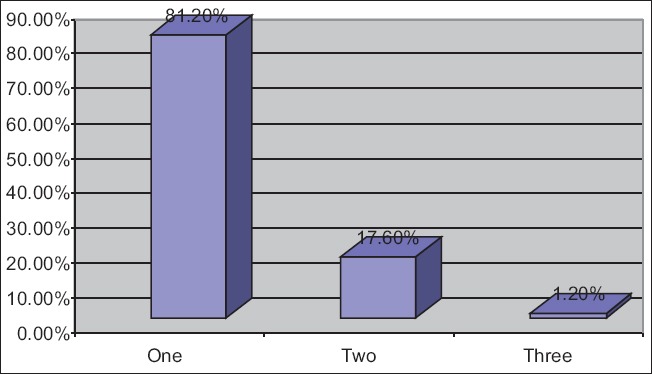

Analysis of the colonoscopic findings showed that 203 (81.2%) of the patients had only one abnormality detected, 44 (17.6%) had two abnormalities while 3 (1.2%) had three abnormalities detected [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Number of colonoscopic abnormalities per patient

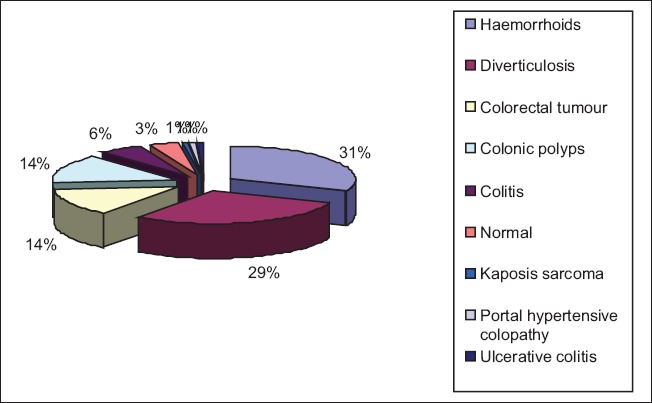

In patients that presented with hematochezia, the most frequent colonoscopic abnormalities were hemorrhoids in 36 (31%), diverticulosis in 34 (29.3%), colorectal tumor in 16 (13.8%), and colonic polyps also in 16 (13.8%) patients [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Spectrum of colonoscopic abnormalities in patients with hematochezia

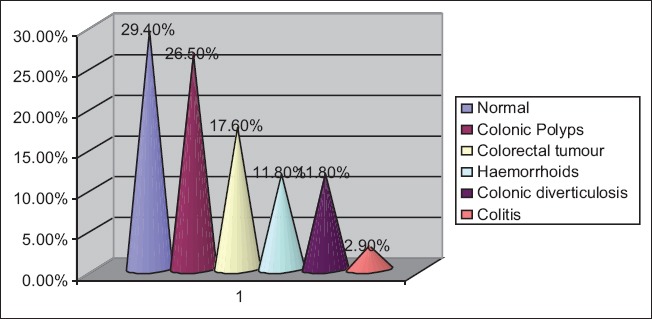

Among patients with constipation as their indication, the findings were normal in 10 (29.4%), colonic polyps in 9 (26.5%), and colorectal tumor in 6 (17.6%) patients [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Spectrum of colonoscopic abnormalities in patients with constipation

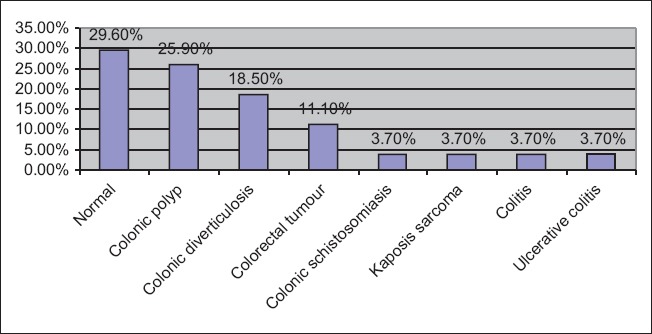

The colonoscopic findings found in patients that presented with diarrhea were normal in 8 (29.6%), colonic polyps in 7 (25.9%), and colonic diverticulosis in 5 (18.5%) patients [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Spectrum of colonoscopic abnormalities in patients with diarrhea

Discussion

Colonoscopy has been found useful both for diagnosis and therapeutic purposes. It is particularly useful for vivid appreciation and diagnosis of small lesions compared with other imaging procedures, because of possibilities of use of dyes and narrow band imaging in addition. This study revealed that more males presented for colonoscopy compared to females. This trend was also observed in other studies.[9,10] The conservative nature of women might explain the gender difference.

The majority of our patients in this study were in the middle age (mean age was 57.9 ± 14.2 years). This is comparable to the finding of Alatise et al.,[11] at Ife, which is in the same geographical zone where our study was carried out. It is also comparable to the finding of Cahyono et al.,[12] in Indonesia. However, it is much higher than what was observed by Sayeed et al.,[10] (mean age 35 years) in Bangladesh. The younger age reported in their study might be explained by the fact that the most common indication for colonoscopy was IBS, which is seen mostly in young individuals.

In this study, the most common indication for colonoscopy was hematochezia. This was similar to the observation in other studies conducted in other parts of the country,[11,13] as well as those conducted in other parts of the world.[12,14] However, in the study by Sayeed et al.,[10] in Bangladesh, the most common indication was clinical suspicion of IBS whereas, Sahu et al.,[9] in India, Ogutu et al.,[15] in Kenya and Al-Shamali et al.,[16] in Kuwait found lower abdominal pain to be the most common indication for colonoscopy.

The overall diagnostic yield of colonoscopy in this study was 74%. This figure is slightly higher than what was reported by Irabor (71%),[7] who carried out similar study at the same center about a decade earlier. This slight difference might be explained by the higher sample size in this study. The difference in the type of equipment used might have also played a role. In this study, a better model of videocolonoscope was used which could have detected more lesions compared to what was used 9 years ago. The diagnostic yield in this study is also comparable to the diagnostic yields reported by studies carried out in other parts of the country.[8,11,13]

However, our figure is higher than the 61.9% reported by Mahomed et al.,[17] in South Africa. Although the sample size in their study was much higher than in this study, the majority of their patients were Caucasians, as only 25.9% were of black ethnicity compared to our study where all the patients were black. Probably, this racial difference might be a factor. However, in another study by Dakubo et al.,[18] in Ghana where all their patients were black, a lower diagnostic yield (48.4%) was also recorded. This shows that other factors apart from race might be responsible for these differences in the diagnostic yield. Furthermore, some studies in other parts of the world have reported much lower diagnostic yields than in this study.[9,12,14,16,19] Differences in indications, as well as the spectrum of colonic diseases in different parts of the world might also be of importance.

It has been observed that hematochezia has the highest diagnostic yield in many studies.[10,11,12,13,14,16,18] Considering the fact that hematochezia was the most common indication for colonoscopy in this study, this might also be another reason for the high diagnostic yield observed.

From this study, the most common abnormality seen at colonoscopy was colonic polyps. This is in contrast to the finding of Irabor,[7] where colon cancer was reported to be the most common finding at colonoscopy. The small sample size in that study might be a factor for this observation.

Our findings at colonoscopy also contrasts the findings of Olokoba et al.,[13] in Ilorin, Ismaila and Misauno[8] in Jos and Alatise et al.,[11] in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, who reported colorectal cancers and hemorrhoids respectively as the most common pathology at colonoscopy. Furthermore, in other parts of the world, Dakubo et al.,[18] Cahyono et al.,[12] and Al-Shamali et al.,[16] reported hemorrhoids, colorectal cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease, respectively as the most common diagnosis at colonoscopy. Reasons for varying findings at colonoscopy may be explained by differences in lifestyle, race, geographic locations, diets, behavioral, and environmental factors as well as the experience of the colonoscopist.

However, this finding of our study is similar to that of Mahomed et al.,[17] who also reported colonic polyps as the most common pathology at colonoscopy. Although colonic polyps are said to be rare in blacks, the report of our study has proven otherwise. Increase in the incidence of polyps as found in this study may be due to an increase in the number of individuals that present for colonoscopy, the use of a high-resolution videocolonoscope, as well as westernization of lifestyle and diet by blacks in recent times.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that colonoscopy is an effective means of diagnosing colonic diseases and that the diagnostic yield could be high if the indication were appropriate. The most common indication in this study was hematochezia, and the most frequent diagnosis was colonic polyps at our center.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank all the nurses and other support members of staff of the Endoscopy Unit of the University College Hospital, Ibadan for their dedication and support during this study.

References

- 1.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: Recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grassini M, Verna C, Niola P, Navino M, Battaglia E, Bassotti G. Appropriateness of colonoscopy: Diagnostic yield and safety in guidelines. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1816–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Lieberman DA, Burt RW, Sonnenberg A. Colorectal Cancer Prevention 2000: Screening recommendations of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:868–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman DA, De Garmo PL, Fleischer DE, Eisen GM, Helfand M. Patterns of endoscopy use in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:619–24. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonvers JJ, Froehlich F, Burnand B, Vader JP, Wietlisbach V The European EPAGE Study Group. A European view of appropriateness and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: A multicentre study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:A574. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arigbabu AO, Odesanmi WO. Colonoscopy. First experience in Nigeria. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:728–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02560287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irabor DO. Surgical gastrointestinal endoscopy in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res. 2006;8:161–2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismaila BO, Misauno MO. Colonoscopy in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. J Med Trop. 2011;13:172–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahu SK, Husain M, Sachan P. Clinical spectrum and diagnostic yield of lower gastrointestinal endoscopy at a tertiary centre. Internet J Surg. 2009;18:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayeed A, Islam R, Siraj D, Hoque G, Mohsen AQ. Colonoscopy: A study of findings in 332 patients. J Chittagong Med Coll Teach Assoc. 2007;18:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alatise OI, Arigbabu AO, Agbakwuru EA, Lawal OO, Ndububa DA, Ojo OS. Spectrum of colonoscopy findings in Ile-Ife Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2012;19:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahyono SB, Bayupurnama P, Ratnasari N, Catharina T, Fahmi I, Sutanto M, et al. Evaluating indications and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy in Sardjito general hospital. J Int Med Acta Int. 2014;4:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Bojuwoye MO, Olatoke SA, Bolarinwa OA, Olokoba LB. Indications and findings at colonoscopy in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2013;54:111–4. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.110044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassa E. Colonoscopy in the investigation of colonic diseases. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:741–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogutu EO, Okoth FA, Lule GN. Colonoscopic findings in Kenyan African patients. East Afr Med J. 1998;75:540–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Shamali MA, Kalaoui M, Hasan F, Khajah A, Siddiqe I, Al-Nakeeb B. Colonoscopy: Evaluating indications and diagnostic yield. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:304–7. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2001.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahomed AD, Cremona E, Fourie C, Dhlamini L, Klos M, Ntshalintshali T, et al. A clinical audit of colonoscopy in a gastroenterology unit at a tertiary teaching hospital in South Africa. South Afr Gastroenterol Rev. 2012;10:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dakubo JC, Seshie B, Ankrah LN. Utilization and diagnostic yield of large bowel endoscopy at Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. J Med Biomed Sci. 2014;3:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddique I, Mohan K, Hasan F, Memon A, Patty I, Al-Nakib B. Appropriateness of indication and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy:First report based on the 2000 guidelines of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7007–13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]