Abstract

Background:

Stroke can be prevented with treatments targeted at hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and atrial fibrillation, but this is often hampered by under-diagnosis and under-treatment of those risk factors. The magnitude of this problem is not well-studied in sub-Saharan Africa.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of stroke patients at a tertiary hospital during January 2010 to July 2013 to determine patient awareness of a pre-existing stroke risk factor and prior use of anti-hypertensive, anti-diabetic, antiplatelet and lipid-lowering agents. We also investigated whether gender and school education influenced patient awareness and treatment of a stroke risk factor prior to stroke.

Results:

Three hundred and sixty nine stroke patients presented during the study period, of which 344 eligible subjects were studied. Mean age at presentation (±SD) was 55.8 ± 13.7 years, and was not different for men and women. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and atrial fibrillation were prevalent among 83.7%, 26.5%, 25.6% and 9.6% patients respectively. Awareness was high for pre-existing diabetes (81.8%) and hypertension (76.7%), but not for hyperlipidemia (26.4%) and atrial fibrillation (15.2%). Men were better educated than women (p = 0.002), and had better awareness for hyperlipidemia (37.3% versus 13.5%; p = 0.009). Men were also more likely to take drug treatments for a stroke risk factor, but the differences were significant.

Conclusions:

A high rate of under-diagnosis and under-treatment of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and atrial fibrillation contributes to the stroke burden in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among women. Public health measures including mass media campaigns could help reduce the burden of stroke.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, stroke, Fibrillation auriculaire, le diabète, l’hyperlipidémie, l’hypertension, accident vasculaire cérébral

Résumé

Contexte:

L’AVC peut être évitée avec des traitements ciblant l’hypertension, le diabète sucré, hyperlipidémie et la fibrillation auriculaire, mais cela est souvent entravée par le sous-diagnostic et sous-traitement de ces facteurs de risque. le l’ampleur de ce problème ne sont pas bien étudié en Afrique sub-saharienne.

Matériels et Méthodes:

Nous avons mené une enquête transversale des patients d’AVC dans un hôpital tertiaire au cours Janvier 2010 à Juillet 2013 pour déterminer la sensibilisation des patients d’un facteur de risque d’accident vasculaire cérébral préexistante et l’utilisation préalable du antihypertenseur, antidiabétique, anti-agrégant plaquettaire et des agents hypolipidémiants. Nous avons également cherché à savoir si le sexe et l’école l’éducation a influencé la sensibilisation et le traitement d’un facteur de risque d’accident vasculaire cérébral avant AVC patient.

Résultats:

Trois cent soixante-neuf patients d’AVC présentés au cours de la période d’étude, dont 344 éligibles les sujets ont été étudiés. L’âge moyen à la présentation (± écart-type) était de 55,8 ± 13,7 années, et n’a pas été différent pour les hommes et femmes. Hypertension, l’hyperlipidémie, le diabète et la fibrillation auriculaire étaient fréquentes chez les 83,7%, 26,5%, 25,6% et 9,6% des patients, respectivement. La sensibilisation a été élevé pour le diabète pré-existant (81,8%) et l’hypertension (76,7%), mais pas hyperlipidémie (26,4%) et la fibrillation auriculaire (15,2%). Les hommes étaient plus instruits que les femmes (p = 0,002), et avait une meilleure prise de conscience de l’hyperlipidémie (37,3% versus 13,5%; p = 0,009). Les hommes étaient également plus susceptibles de prendre traitements médicamenteux pour un facteur de risque d’accident vasculaire cérébral, mais les différences étaient significatives.

Conclusions:

Un taux élevé de sous-diagnostic et sous-traitement de l’hypertension, l’hyperlipidémie et l’auriculaire fibrillation contribue à la charge de l’AVC en Afrique sub-saharienne, en particulier chez les femmes. Mesures de santé publique y compris les campagnes médiatiques pourrait aider à réduire le fardeau de la course.

Introduction

Stroke caused 6.7 million deaths worldwide in 2012 and is now the second highest cause of death after heart disease.[1] Major stroke risk factors include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation (AF), with hypertension alone involving 54% of all strokes and another 20% of strokes attributed to the combined effects of diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and AF.[2,3]

Stroke incidence and mortality can be reduced with lifestyle changes and use of antihypertensive, antidiabetic, antiplatelet, and lipid-lowering drugs.[4,5,6,7] A meta-analysis of randomized trials showed antihypertensive drug treatment alone reduced stroke risk by 36% while the use of fibrates or statins to lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol resulted in a 30% reduction in stroke risk.[4,5] Other studies show stroke risk with AF, which is as high as 7.6%, can be reduced by two-third with warfarin treatment alone.[6,7]

So far, stroke risk factors are underdiagnosed and undertreated even in developed countries. In parts of the United States, unrecognized hypertension was prevalent among 18.7% of early stroke survivors, and only 42.1% of AF patients at high-risk of stroke were taking warfarin in accordance with guideline recommendations of the American Heart Association.[8,9] Factors that militate against the effective treatment of stroke risk factors include poor access to healthcare services, lack of public awareness, and noncompliance with treatment guidelines by patients and healthcare providers.[8]

Africans manifest some of the world's highest rates of hypertension, and underdiagnosis of hypertension,[10] but few studies have investigated stroke risk factor treatment before stroke in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).[11,12] In the multinational INTERSTROKE study involving five African countries including Nigeria, 83% of stroke survivors had hypertension, which was undiagnosed among 23% at the time of stroke.[11] Other studies have reported higher rates of undiagnosed hypertension and other vascular risk factors among stroke survivors in Africa, but they did not investigate whether demographic or other variables had influences on patient awareness and treatment of those risk factors before stroke.[12]

Thus, we studied a sample of stroke patients to assess their levels of awareness of pre-existing hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and AF and their use of drug treatments for those stroke risk factors before stroke. We also aimed to determine if patient gender and level of education influenced their use of drug treatments targeted at stroke risk factors to lessen the risk of stroke.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the National Hospital Abuja (NHA), a tertiary referral center serving communities in Nigeria's Federal Capital Territory and neighboring Kogi, Niger, Kaduna, and Nasarawa states. All adult patients who presented with stroke between January 2010 and July 2013 were eligible for enrollment. Exclusion criteria were refusal to enroll in the study and absence of a knowledgeable proxy for critically-ill or aphasic patients. Ethical clearance was obtained from the NHA institutional review board, and patients or their close family members signed informed consent. Data were collected using questionnaires, which recorded subjects’ age, gender, educational attainment, occupation, presence of vascular risk factors before stroke, and use of prescription drugs to treat vascular risk factors.

For the benefit of uneducated respondents, the terms “hypertension,” “diabetes mellitus,” “hyperlipidemia,” and “AF” were explained in parentheses as “raised blood pressure,” “raised blood sugar,” “elevated blood cholesterol,” and “abnormal heart rhythm,” respectively. Educational attainment was categorized as “no education” for subjects who never attended a formal school or had not completed primary school, “primary/secondary education” for those who completed primary or secondary education, and “tertiary education” for those with at least 2 years of postsecondary education and were certified with a college diploma or degree. Patient and proxy interviews were conducted by two neurologists and two neurology residents trained in administering the questionnaire.

All patients were examined by a neurologist who noted cardiovascular and neurologic signs at admission and during inpatient care. Stroke was defined according to the WHO criteria.[3] Hypertension was defined as a previous physician diagnosis of hypertension or blood pressure readings consistently ≥140/90 mmHg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a previous physician diagnosis or fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/L. Hyperlipidemia was deemed to be present if a patient had been prescribed lipid-lowering agents by a physician, or had serum total cholesterol >240 mg/dL, triglycerides >200 mg/dL, or LDL cholesterol >160 mg/dL.[13] AF was defined as the absence of P-waves on a routine electrocardiogram (ECG) or Holter monitor. Holter monitoring was requested only for those patients with presumed cardioembolic stroke in whom a routine ECG did not detect AF.

Use of the following medications by patients before a stroke was verified from them or their proxies: Antihypertensive drugs; insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents; lipid-lowering agents; and oral antiplatelets and anticoagulants. Drugs were identified through mention of their generic and brand names, and inspection of pills and prescription notes by study investigators. Every effort was made to have drugs kept at home brought to the hospital for inspection, but when that was not possible and informants could not name the drug correctly, investigators had other family members read out the drug name through telephone interviews. We did not seek to determine if patients had complied with physician-prescribed treatment, or whether prescriptions had followed recommended guidelines for stroke prevention in patients at risk.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows version 22.0 software (IBM Corporation, New York). Means of continuous variables were compared using Student's unpaired t-test, while categorical variables were analyzed by Chi-square tests. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 369 stroke patients presented during the study period, of which 344 fulfilled inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. This comprised 223 men and 121 women (M:F = 1.8:1). Mean age at presentation was 55.8 ± 13.7 years (±standard deviation) and was not different between men and women (56.7 ± 13.0 vs. 54.3 ± 14.9; P = 0.12). Of the 25 excluded patients, 19 had died early or suffered aphasia or depressed levels of consciousness in the absence of knowledgeable informants, whereas six patients absconded or left against medical advice with incomplete data. No patient declined participation in the study. The age and gender distribution of excluded subjects were not different from study subjects.

The most common stroke subtype was cerebral infarction, which was confirmed on brain imaging in 62.5% patients, followed by intracerebral hemorrhage (30.5%) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (2.9%). Brain imaging was not performed in 4.1% patients, mainly due to financial constraints. Stroke categories showed no significant differences between male and female subjects (P = 0.20).

Hypertension was the most common stroke risk factor [Table 1], being present in 83.7% patients, followed by hyperlipidemia (26.5%), diabetes mellitus (25.6%), and AF (9.6%). Only 76.7% hypertensive subjects were aware of their status before a stroke, and only 69.8% were on drug treatment before a stroke. Among diabetic subjects, 81.8% knew of their status before they had stroke, and 73.9% had been on hypoglycemic drug treatment. Corresponding rates for hyperlipidemia and AF are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The diagnosis of AF relied on routine ECGs performed on 339 patients, and 24-h Holter monitoring performed on 27 patients with suspected cardioembolic stroke but in whom ECGs did not reveal AF. Of the 33 cases of AF, 28 were detected by routine ECG while five cases were detected through Holter monitoring.

Table 1.

Biographical, clinical and laboratory data of study subjects

| Clinical and laboratory variable | All patients (n=344) | Men (n=223) | Women (n=121) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years±SD (%) | 55.8±13.7 | 56.7±13.0 | 54.3±14.9 | 0.12 |

| Young: <45 | 73 (21.2) | 40 (17.9) | 33 (27.3) | 0.13 |

| Middle-aged: 45-64 | 175 (50.9) | 119 (53.4) | 56 (46.3) | |

| Elderly: ≥65 | 96 (27.9) | 64 (28.7) | 32 (26.4) | |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||||

| No education | 138 (40.1) | 75 (33.6) | 63 (52.1) | 0.002* |

| Primary or secondary education | 108 (31.4) | 71 (31.8) | 37 (30.6) | |

| Tertiary education | 96 (27.9) | 75 (33.8) | 21 (17.4) | |

| Do not know/not sure | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Risk factor prevalence, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 288 (83.7) | 188 (84.3) | 100 (82.6) | 0.76 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 88 (25.6) | 57 (25.6) | 31 (25.6) | 1.00 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 91 (26.5) | 51 (22.9) | 40 (33.1) | 0.05 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (9.6) | 23 (10.3) | 10 (8.3) | 0.70 |

| Laboratory variables, mean±SD | ||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 156.5±37.3 | 157.9±37.9 | 153.9±36.0 | 0.37 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 94.5±23.0 | 96.0±26.9 | 92.0±21.1 | 0.11 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.3±2.3 | 6.3±2.2 | 6.4±2.5 | 0.80 |

| Serum total cholesterol, mg/dL | 190.0±53.2 | 180.6±49.4 | 207.4±55.9 | <0.001* |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 119.8±46.6 | 114.2±44.2 | 130.9±49.4 | 0.02* |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 45.6±22.5 | 43.6±23.7 | 49.0±20.3 | 0.22 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 118.8±58.6 | 114.1±53.9 | 128.0±66.2 | 0.09 |

*P values reaching statistical significance. SD=Standard deviation, LDL=Low-density lipoprotein, HDL=High-density lipoprotein, BP=Blood pressure

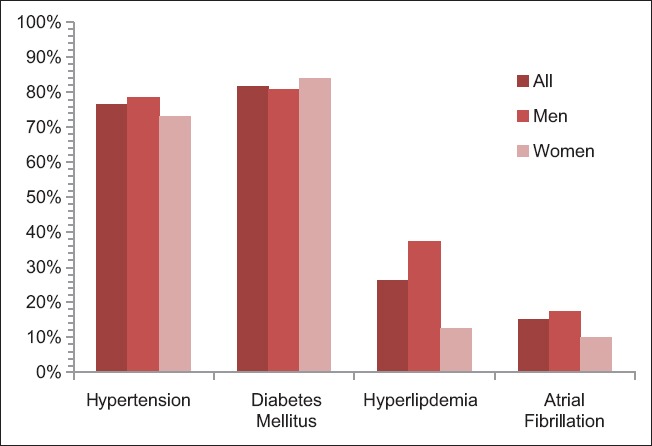

Figure 1.

Rates of patient awareness of having a stroke risk factor prior to stroke

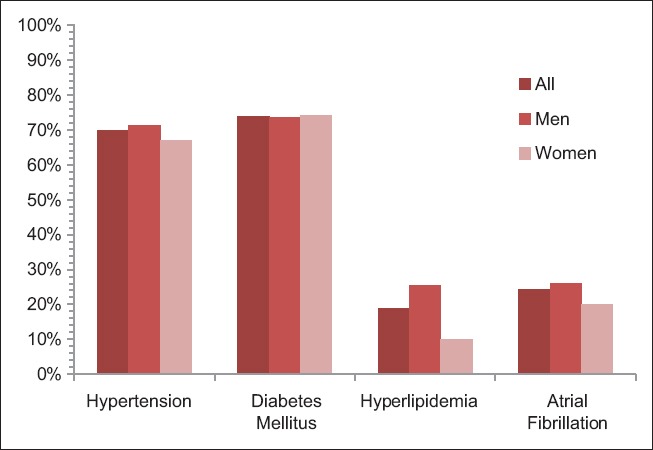

Figure 2.

Treatment rates for stroke risk factors among study subjects prior to stroke

Compared to men, women had significantly lower levels of school education (P = 0.002) and higher levels of mean serum total cholesterol (180.6 ± 49.4 mmol/L vs. 207.4 ± 55.9 mmol/L; P < 0.001) and LDL cholesterol (114.2 ± 44.2 mmol/L vs. 130.9 ± 49.4 mmol/L; P = 0.02). There were no significant differences between men and women in all other measured variables, including age group distribution and prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and AF.

Numerical data for bar chart on Figure 1

| Hypertension | Diabetes mellitus | Hyperlipidemia | Atrial fibrillation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0.767 | 0.818 | 0.264 | 0.152 |

| Men | 0.787 | 0.807 | 0.373 | 0.174 |

| Women | 0.73 | 0.839 | 0.125 | 0.1 |

Percentages were converted to fractions of 1 to conform with excel worksheet properties (e.g., 76.7% was converted to 0.767)

Numerical data for bar chart on Figure 2

| Hypertension | Diabetes mellitus | Hyperlipidemia | Atrial fibrillation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0.698 | 0.739 | 0.187 | 0.242 |

| Men | 0.713 | 0.737 | 0.255 | 0.261 |

| Women | 0.67 | 0.742 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

Percentages were converted to fractions of 1 to conform with excel worksheet properties (e.g., 69.8% converted to 0.698)

Men were more likely to be aware of having a stroke risk factor before the stroke, but this trend was only significant for hyperlipidemia [37.3% for men versus 13.5% for women; P = 0.009, Figure 1] but not for hypertension, AF, or diabetes mellitus. Except for diabetes, men were also more likely to be taking drug treatment for a stroke risk factor, but these differences did not reach statistical significance for any of the four risk factors studied [Figure 2].

Discussion

We have surveyed a sample of stroke patients and determined their levels of awareness and use of drug treatments for four modifiable stroke risk factors before stroke in a Sub-Saharan African society.

The age and sex distribution of our patients are consistent with previous studies showing male preponderance over females among hospitalized stroke patients. Men in our study had also attained higher levels of education compared to women, with over one-third of men having tertiary education compared to only 17% women. While this gender difference likely reflects the average lower educational status of women in Africa, our findings may have over-estimated educational attainment in Nigerian society, where a 2011 demographic survey showed only 21% of male and 15% of female urban-dwellers had some form of tertiary education.[14] Sampling bias may explain our results, considering stroke victims with school education would be more likely to seek hospital treatment.

Hypertension affected over 80% of our patients, but almost a quarter of hypertensives did not know of their status until after a stroke. However, patient lack of awareness was exceptionally high for hyperlipidemia and AF. While almost three-quarters of those with hyperlipidemia did not know of their status before a stroke, this rate exceeded 80% in those with AF. On the contrary, less than a fifth of diabetics lacked knowledge of their clinical condition before a stroke, probably because of a wider public awareness of diabetes and its association with certain symptoms that alert patients to seek early medical care.

Expectedly, our patients were more likely to be on treatment for hypertension and diabetes mellitus than for hyperlipidemia and AF. Indeed, the 24% treatment rate for AF may be spuriously high due to the recommended use of antiplatelet agents to reduce stroke risk in patients with other vascular risk factors. We have observed that among the four stroke risk factors studied, only for AF did drug treatment rates exceed rates of patient awareness of their condition, suggesting that antiplatelet therapy was not necessarily targeted at AF in all patients with that condition. Besides, use of oral anticoagulants and not antiplatelets is the recommended treatment for AF in patients at high-risk of stroke, such as those with CHADS2 scores of 2 or more, according to American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology guidelines.[9] Considering that stroke related to AF is more disabling and carries greater risks of death and disability,[15,16] our findings suggest the need for improved efforts at early detection and appropriate management of AF at primary care settings in SSA.

Still, in absolute terms, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were the most prevalent stroke risk factors left untreated among our patients, contributing, respectively, to 87 (41.6%) and 74 (35.4%) among the total tally of 209 nontreatments of a stroke risk factor before stroke. Untreated diabetes and AF together constituted the remaining 26%. These findings are consistent with those of a recent study in Kumasi, Ghana, which reported hypertension and hypercholesterolemia among the most prevalent but least treated stroke risk factors, with only 51% of hypertensives and 1% of those with hypercholesterolemia having knowledge of their clinical states before a stroke.[17]

Despite the higher educational status of men in our study, we found no significant correlation between male gender and stroke risk factor treatment, even as men with hyperlipidemia knew significantly better than women about their clinical states. This appears to suggest that higher levels of education may aid patient knowledge of having a stroke risk factor but may not necessarily influence the decision to treat. We have no concise explanation for this paradox, but it is probably a result of other unknown variables creating barriers to treatment.

Conclusion

Our study on an African population has shown high rates of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of major stroke risk factors, especially hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and AF. For hyperlipidemia, both disease prevalence and underdiagnosis were higher in women compared to men, but further studies are needed to identify other barriers to patient awareness of stroke risk factors and their use of stroke prevention treatments. Improved access to healthcare services and public awareness campaigns in the mass media could help in the early detection and treatment of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and AF.

Our study has limitations, which include its hospital-based setting. By enrolling only stroke victims attending a hospital, we may have introduced a sampling bias in favor of those with school education. A community-based study could avoid that pitfall, but we lacked the resources needed for that methodology. Another limitation was our failure to assess patient compliance (or adherence) with drug treatments. However, we relied on spouses and other family members for information on very ill and aphasic patients. While these informants often knew a patient's biographical and medical histories, they lacked precise knowledge of patients’ levels of adherence to prescription drugs. For the same reasons, we did not distinguish between patient noncompliance with prescribed treatments and physician noncompliance with recommended guidelines for stroke prevention. Such efforts would require access to case notes at various primary care clinics, which we could not afford.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Fact Sheet No. 310. [Last updated on 2014 May; Last cited on 2015 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/

- 2.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A International Society of Hypertension. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke. [Last updated on 2013 May; Last cited on 2014 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/resources/atlas/en/

- 4.Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension 1. Overview, meta-analyses, and meta-regression analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2285–95. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpérovitch A, Kurth T, Bertrand M, Ancelin ML, Helmer C, Debette S, et al. Primary prevention with lipid lowering drugs and long term risk of vascular events in older people: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2335. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group. Comparison of 12 risk stratification schemes to predict stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2008;39:1901–10. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner DA, Zweifler RM, Gomez CR, Kissela BM, Levine D, Howard G, et al. Awareness, treatment, and control of vascular risk factors among stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimetbaum PJ, Thosani A, Yu HT, Xiong Y, Lin J, Kothawala P, et al. Are atrial fibrillation patients receiving warfarin in accordance with stroke risk? Am J Med. 2010;123:446–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guwatudde D, Nankya-Mutyoba J, Kalyesubula R, Laurence C, Adebamowo C, Ajayi I, et al. The burden of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: A four-country cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1211. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2546-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): A case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watila MM, Nyandaiti YW, Ibrahim A, Balarabe SA, Gezawa ID, Bakki B, et al. Risk factor profile among black stroke patients in North-Eastern Nigeria. J Neurosci Behav Health. 2012;4:50–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (DHS): Education Data for Decision-Making 2011. Washington, DC, USA: National Population Commission (Nigeria) and RTI International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stambler BS, Ngunga LM. Atrial fibrillation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Epidemiology, unmet needs, and treatment options. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:231–42. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S84537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alkali NH, Bwala SA, Akano AO, Osi-Ogbu O, Alabi P, Ayeni OA. Stroke risk factors, subtypes, and 30-day case fatality in Abuja, Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2013;54:129–35. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.110051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarfo FS, Acheampong JW, Appiah LT, Oparebea E, Akpalu A, Bedu-Addo G. The profile of risk factors and in-patient outcomes of stroke in Kumasi, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2014;48:127–34. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v48i3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]