Abstract

Background:

Induction of labor (IOL) is an artificial initiation of labor before its spontaneous onset for the purpose of delivery of the fetoplacental unit. Many factors are associated with its success in postdatism.

Objective:

To compare the induction delivery intervals using transcervical Foley catheter plus oxytocin and vaginal misoprostol, and to identify the factors associated with successful induction among postdate singleton multiparae.

Materials and Methods:

The study was a prospective randomized controlled trial of singleton multiparous pregnant women. They were randomized into two groups, one group for intravaginal misoprostol and the other group for transcervical Foley catheter insertion as a method of cervical ripening and IOL. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 17 computer software (SPSS Inc., IL, Chicago, USA). Comparisons of categorical variables were done using Chi-squared test, with P < 0.05 considered as significant. Student's t-test was used for continuous variables.

Results:

The incidence of postdatism was found to be 136 (13.1%). The mean induction delivery time interval was shorter in the misoprostol group 70 (5.54 ± 1.8 h) than in the Foley catheter oxytocin infusion group 66 (6.65 ± 1.7 h) (P = 0.035). There was, however, no statistically significant difference in the maternal and neonatal outcomes when these two agents were used for cervical ripening and IOL. Higher parity and higher Bishop's score were the factors found to be associated with high success rate of IOL (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Vaginal misoprostol resulted in shorter induction delivery time interval as compared to transcervical Foley catheter. High parity and high Bishop's scores were the factors found to be associated with the success of IOL.

Keywords: Induction delivery interval, Kano, misoprostol, postdatism, transcervical catheter, Intervalle de livraison par induction, Kano, misoprostol, postdatism, transcervicale cathéter

Résumé

Contexte:

l’induction du travail (IOL) est un artificial déclenchement du travail avant son apparition spontanée aux fins de livraison de l’unité fetoplacental. De nombreux facteurs sont associés à son succès en postdatism.

Objectif:

Pour comparer les intervalles de livraison d’induction à l’aide d’transcervicale cathéter de Foley, plus l’oxytocine et vaginal misoprostol, et d’identifier les facteurs associés au succès de l’induction chez postdatent multiparae singleton.

Matériels et Méthodes:

l’étude a été un essai randomisé contrôlé prospectif de singleton multipare les femmes enceintes. Ils ont été randomisés en deux groupes : l’un pour l’ autre misoprostol et intravaginale Groupe pour l’insertion du cathéter de Foley transcervicales comme méthode de maturation du col et iol. Les données ont été analysées à l’aide de SPSS version 17 computer software (SPSS Inc., HE, Chicago, États-Unis). Les comparaisons des variables catégoriques ont été effectuées à l’aide du test chi-carré, avec P < 0,05 considérées comme significatives. Le test t de Student a été utilisé pour les variables continues.

Résultats:

L’incidence de postdatism a été trouvé à 136 (13,1 %). L’ intervalle de temps de livraison d’induction moyenne était plus courte dans le misoprostol groupe 70 (5,54 ± 1,8 h) que dans le cathéter de Foley oxytocine groupe infusion 66 (6,65 ± 1,7 h) (P = 0,035). Il y a, toutefois, aucune différence statistiquement significatives de différence dans les résultats maternels et néonatals lorsque ces deux agents ont été utilisées pour la maturation du col et IOL. Plus élevé et une plus grande parité Bishop’s score étaient les facteurs associés aux taux de réussite élevé de terres inuites (P < 0,001).

Conclusion:

VAGINAL MISOPROSTOL entraîné plus court intervalle de temps de livraison d’induction par rapport à transcervicale cathéter de Foley. La parité élevée et haute Bishop’s notes étaient les facteurs associés à la réussite de terres inuites.

Introduction

Induction of labor (IOL) at term is a common obstetric intervention with many indications among which the most common is postdatism.[1,2]

About 15% of all gravid women with unfavorable Bishop's score may need cervical ripening[3,4,5,6,7] for IOL. IOL is a technique for initiating uterine contraction to achieve delivery of the fetoplacental unit before the onset of spontaneous labor.[8]

Postdatism, which has been known to be the most common indication of IOL, has an average frequency of 10%[9,10,11] and occurs when pregnancy exceeds 40 weeks of gestational age (GA) beyond which pregnancy is advised to be terminated because of possible deterioration of placental function, which may jeopardize the intrauterine state of the fetus and can result in significant increase in perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as increased risk to the mother.[12,13]

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that labor should be electively induced at 41 weeks of GA instead of expectant management.[14,15,16] Although there are many methods for cervical ripening, there is no agreement in the choice of best and most proper method of cervical ripening, before IOL. The study was aimed to add to the existing literature and assist in providing the best method that gives maternal and neonatal outcomes and also short average induction delivery time interval.

Materials and Methods

The study was a prospective randomized controlled trial among all consenting postdate singleton pregnant multigravidae who booked for an antenatal clinic at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital and planned for IOL. Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the hospital ethical committee. It was conducted from February 01 to May 30, 2015.

The patients were recruited from the antenatal ward at 41 weeks 3 days GA for IOL with an unfavorable cervix. This was based on the hospital protocol. An informed consent was sought and obtained from each patient before recruitment.

A pretested questionnaire was administered before and completed after the delivery by the investigators until the minimum sample size was attained. Information recorded on the questionnaire included sociodemographic factors, last menstrual period, gravidity, parity, and GA. Others such as methods of delivery, maternal and perinatal outcomes were also obtained, and their respective responses were recorded. Computer-generated random numbers were used to allocate the study groups into either Foley catheter or vaginal misoprostol. The induction to delivery interval was calculated from cervical dilatation of 4 cm to the delivery of the fetus. The APGAR scores, maternal vital signs, estimated blood loss, and induction to delivery interval were recorded on the questionnaire.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 17 computer software (SPSS Inc., IL, Chicago, USA). Comparison of categorical variables was done using Chi-square test with P < 0.05, which was considered significant. Student's t-test was used for continuous variables.

Results

Data of one hundred and thirty-six participants were analyzed. The total number of deliveries during the period was 1038. The rate of IOL among multiparous pregnant women, who were carrying singleton fetuses, was found to be 136 (13.1%) of all deliveries.

The participants were comparable in their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics; the differences observed were not statistically significant [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of participants by their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics

| Variable | Misoprostol group (n=70) (%) | Foley catheter (plus oxytocin infusion) group (n=66) (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |||

| <20 | 10 (14.3) | 5 (7.6) | χ2=3.52 |

| 20-34 | 45 (64.3) | 52 (78.8) | P=0.169 |

| ≥35 | 15 (21.4) | 9 (13.6) | |

| Educational status of the participants | |||

| Nil | - | - | χ2=1.1 |

| Primary school | 14 (20.0) | 18 (27.3) | P=0.06 |

| Secondary school | 30 (42.9) | 27 (49.9) | |

| Tertiary education | 26 (37.1) | 21 (31.8) | |

| Religion | |||

| Islam | 62 (88.6) | 63 (95.5) | χ2=1.34 |

| Christianity | 8 (11.4) | 3 (4.5) | P=0.25 |

| Tribe | |||

| Hausa | 50 (71.4) | 51 (77.2) | χ2=1.06 |

| Fulani | 8 (11.4) | 9 (13.6) | P=0.58 |

| Igbo | None | 3 (4.6) | |

| Yoruba | 6 (8.6) | None | |

| Others | 6 (8.6) | 3 (4.6) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Homemaker | 48 (68.6) | 48 (72.7) | χ2=3.37 |

| Civil servant | 4 (5.7) | 6 (9.1) | P=0.34 |

| Student | 10 (14.2) | 6 (9.1) | |

| Trader | 2 (2.9) | 6 (9.1) | |

| Others | 6 (8.6) | None |

The majority of the participants in both groups belonged to the age group of 20–34, 45 (64.3%) and 52 (78.8%) in the misoprostol and intracervical Foley catheter group, respectively.

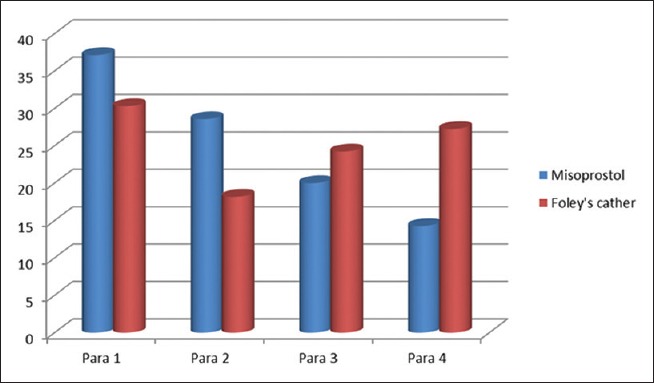

Figure 1 shows that para 1 from the misoprostol and Foley catheter groups were 26 (37.1%) and 20 (30.3%), respectively. Whereas 18 (27.3%) and 10 (14.3%) had a parity of 4 in the Foley catheter and misoprostol group, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the patients based on their parity

The differences were not statistically significant (χ2 = 5.09, P = 0.165). None had ventouse- or forceps-assisted vaginal delivery.

The majority of the participants from both groups had spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD); 14 patients had cesarean delivery in the vaginal misoprostol group.

Table 2 shows the number of neonates who had greenish meconium-stained amniotic fluid and failure to progress in the second stage of labor.

Table 2.

Mode of delivery, indications for cesarean section, and the induction to delivery interval of the studied group

| Groups | Misoprostol group (n=70) (%) | Foley catheter (plus oxytocin infusion) group (n=66) (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVD | 56 (80.0) | 60 (90.9) | χ2=3.22 |

| C/S | 14 (20.0) | 6 (9.1) | P=0.073 |

| Total | 70 (100) | 66 (100) | |

| Indications for cesarean section | Misoprostol group (n=14) (%) | Foley catheter (plus oxytocin infusion) group (n=6) (%) | |

| No progress in the 2nd stage of labor | 10 (71.4) | 6 (100) | |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid (thick greenish) | 4 (28.6) | None | |

| Total | 14 (100) | 6 (100) | |

| Induction to delivery interval | Misoprostol group (n=70) | Foley catheter (plus oxytocin infusion) group (n=66) | P |

| Induction to delivery period (from cervical dilation of 4 and above) | 5.54±1.8 h | 6.65±1.7 h | 0.035 |

SVD: Spontaneous vaginal delivery, C/S: Cesarean section

The induction delivery interval was seen to be shorter in the misoprostol group and longer in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group. The difference was statistically significant [Table 2].

The mean 1st min APGAR scores were found to be 7.36 ± 1.2 and 7.60 ± 1 and that of the 5th min were 8.96 ± 8.04 and 8.90 ± 0.72 in the misoprostol group and Foley catheter plus oxytocin group, respectively [Table 3]. The differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.46; 1st min and P = 0.78; 5th min, respectively).

Table 3.

Outcome measures

| Groups | Misoprostol group (n=70) | Foley catheter (plus oxytocin infusion) group (n=66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| APGAR scores | |||

| The mean first minute APGAR score | 7.36±1.2 | 7.60±1 | 0.46 |

| The mean fifth minute APGAR score | 8.96±0.84 | 8.90±0.72 | 0.78 |

| Bishop’s score | Mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin group (n=60) | Mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery in the misoprostol group (n=56) | P<0.05 |

| 0-2 | 37±8.3 h | 25.32±7.28 h | <0.001 |

| 3-5 | 22.85±7.4 | 9.64±3.7 h | <0.001 |

| Interventions (%) | |||

| Failed induction of labor | 14 (20.0) | 6 (9.1) | χ2=48.7 P<0.0001 |

| Need for amniotomy | 50 (71.4) | 48 (72.7) | |

| Need for oxytocin infusion | 6 (8.6) | 48 (72.7) | |

| Use of episiotomy | 38 (54.3) | 12 (18.2) |

Failed IOL was more in the vaginal misoprostol group [Table 3].

All the participants had an ultrasound scan, 38 (28%) had it in the 1st trimester, 45 (33%) had it in the 2nd trimester whereas 53 (39%) had it in the 3rd trimester.

The mean gestation age at booking was found to be 24.53 ± 7.2 weeks. All the fetuses, i.e., 136 (100%) had reassuring cardiotocography findings.

Only 60 (44.1%) patients remembered their last menstrual period, whereas 57 (41.9%) remembered the birth weight of their neonate(s) at birth. The number of times misoprostol (fifty micro grams) used was only once in 26 (37.1%), twice in 28 (40.0%), thrice in 6 (8.6%), and 4 times in 10 (14.3%). Forty-two (63.6%) had the agent passed once whereas 24 (36.4%) had the agent passed twice. The mean maternal blood loss was found to be 161 ± 54.3 ml in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group and 151 ± 37.55 ml in the misoprostol group.

No pregnant woman had pyrexia in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group whereas 10 (14.3%) patients developed pyrexia in the misoprostol group.

On the distribution of the neonates based on sex, 72 (52.9%) were males, whereas 64 (47.1%) were females. The need for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission was observed in 2 (2.9%) neonates and they were both from the misoprostol group, none from the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group. The number of patients that had previous IOL from the misoprostol group was 8 (11.4%) whereas in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group, it was 9 (13.6%).

The mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery is shown in Table 4. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

The mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery with respect to parity

| Parity | The mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery with respect to parity in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin group (n=60) (h) | The mean total time from insertion of the agent to delivery with respect to parity in the misoprostol group (n=56) (h) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 35.55±9.7 | 24.29±7.1 | <0.001 |

| 3-4 | 17.90±6.65 | 10.68±2.45 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The incidence of postdatism within the study period was found to be 13.1% of all deliveries in the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. This was higher than 6.9% reported by Naeye.[17] This was probably because they used early ultrasound scan for dating of pregnancies during their study period, which is more accurate than the one done late in pregnancies. Late ultrasound scanning done in this study could have contributed to the high incidence. The incidence was, however, lower than 17% reported by Hovi et al.[18]

The rate of SVD was found to be 90.9% in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin group and 80% in the misoprostol group. This was comparable to the findings of Ekele and Isah[19] where the success rate for misoprostol used for IOL was 96% and that of the intracervical Foley catheter was 91%. Owolabi et al.[20] reported that the success rate between vaginal misoprostol and intracervical Foley catheter used for IOL was the same. In this study, the difference was probably because the number of patients who had no progress in the 2nd stage of labor was higher in misoprostol group (10) than that of Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion (six). There was no case of fetal distress or meconium-stained liquor in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group. The difference was, however, not statistically significant (P = 0.073).

There was no statistically significant difference in the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the study group. This provides adequate basis for comparison.

The mean induction to delivery time interval, which was from the time the Bishop's scores became favorable (inducible) to the delivery of the fetus, was found to be shorter in the misoprostol group (5.54 ± 1.8 h) than that of the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group (6.65 ± 1.7 h). Student's t-test was used to test for significance, and the result was statistically significant (P = 0.035). The finding was comparable to similar studies done elsewhere.[20,21,22,23]

None of the neonates from the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group had thick, greenish meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Whereas 4 (5.7%) of the neonates in the misoprostol group had meconium-stained amniotic fluid. The result was similar to the finding of Jindal et al.,[22] but lower than that obtained by Vahid Roudsari et al.[24]

The need for neonatal intensive care admission was found to be 2.9% among the neonates who were delivered from mothers who had their labor induced with misoprostol, whereas none from the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group needed intensive care admission. This was also comparable to the findings by Jindal et al.,[22] while Owolabi et al.[20] showed no difference in ICU admissions between the two groups.

Cesarean delivery rates were found to be 14 (20.0%) from the misoprostol group and 6 (9.1%) from the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.073). The findings were similar to other findings elsewhere.[20,21,22,23,24]

Uterine tachysystole did not occur in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group, but 2.9% of patients who had their labor induced with vaginal misoprostol had uterine tachysystole. The findings were similar to those from Vahid Roudsari et al.[24] in Iran, but lower than the findings from Jindal et al.[22] in India. This was probably because of the higher number of times the misoprostol was used (up to six doses).

Pyrexia was found to occur in 10 (14.3%) patients in the misoprostol group, but none from the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group.

The mean maternal blood loss was 151 ± 37.55 ml in the misoprostol group and 161 ± 54.3 ml in the Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion group. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.437). None of the patients had primary postpartum hemorrhage in either group.

Higher Bishop's scores and higher parity were the factors found to be associated with high success rates of IOL. The differences in the results were statistically significant (P < 0.001). These were comparable to the findings elsewhere.[23,25]

Conclusion

The incidence of postdatism among multiparous pregnant women was found to be 13.1% of all deliveries. Use of vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and IOL was found to result in shorter induction to the delivery time interval when compared to intracervical Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion.

There was, however, no statistically significant difference in the maternal and neonatal outcomes when these two agents were used for cervical ripening and IOL.

Higher Bishop's scores and higher parity were the factors found to be associated with high success rate of IOL among those who had SVD.

Limitation of the study

The indication for IOL in this study was only postdatism; hence, the findings cannot be generalized on patients who have other indications for labor induction.

Recommendation

The use of vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and IOL, among postdate multiparous singleton pregnant women, is recommended and preferred over Foley catheter plus oxytocin infusion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lawani OL, Onyebuchi AK, Iyoke CA, Okafo CN, Ajah LO. Obstetric outcome and significance of labour induction in a health resource poor setting. Obstet Gynecol Int 2014. 2014:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2014/419621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bako BG, Obed JY, Sanusi I. Methods of induction of labour at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri: A 4-year review. Niger J Med. 2008;17:139–42. doi: 10.4314/njm.v17i2.37272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbele AM, Makin JD, Pattinson RC. Can the outcome of induction of labour with oral misoprostol be predicted. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:289–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choy-Hee L, Raynor BD. Misoprostol induction of labor among women with a history of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1115–7. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher H, Mitchell S, Frederick J, Simeon D, Brown D. Intravaginal misoprostol versus dinoprostone as cervical ripening and labor-inducing agents. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:244–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartusevicius A, Barcaite E, Nadisauskiene R. Oral, vaginal and sublingual misoprostol for induction of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ, et al. Births: Final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Results of an epidemiologic study of postdate pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1986;31:162–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayburn WF, Chang FE. Management of the uncomplicated postdate pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1981;26:93–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beischer NA, Evans JH, Townsend L. Studies in prolonged pregnancy. I. The incidence of prolonged pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;103:476–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)31849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilder L, Costeloe K, Thilaganathan B. Prolonged pregnancy: Evaluating gestation-specific risks of fetal and infant mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: Population based analysis. BMJ. 1999;319:287–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rand L, Robinson JN, Economy KE, Norwitz ER. Post-term induction of labor revisited. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):779–83. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellmann J, Hewson S, Milner R, Willan A. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. The Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1587–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowley P. Interventions for preventing or improving the outcome of delivery at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000170. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naeye RL. Causes of perinatal mortality excess in prolonged gestations. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:429–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hovi M, Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Obstetric outcome in post-term pregnancies: Time for reappraisal in clinical management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:805–9. doi: 10.1080/00016340500442472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekele BA, Isah AY. Cervical ripening: How long can the Foley catheter safely remain in the cervical canal? Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owolabi AT, Kuti O, Ogunlola IO. Randomised trial of intravaginal misoprostol and intracervical Foley catheter for cervical ripening and induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25:565–8. doi: 10.1080/01443610500231450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekele BA, Nnadi DC, Gana MA, Shehu CE, Ahmed Y, Nwobodo EI. Misoprostol use for cervical ripening and induction of labour in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10:234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jindal P, Gill BK, Tirath B. A comparison of vaginal misoprostol versus Foley catheter with oxytocin for induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2007;57:42–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferdous J, Khanam NN, Begum MR, Akhter S. Cervical ripening: Comparative study between intra-cervical ballooning by Foley catheter and by intra-vaginal misoprostol tablet. J Bangladesh Coll Phys Surg. 2009;27:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vahid Roudsari F, Ayati S, Ghasemi M, Hasanzadeh Mofrad M, Shakeri MT, Farshidi F, et al. Comparison of vaginal misoprostol with Foley catheter for cervical ripening and induction of labor. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10:149–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonen R, Degani S, Ron A. Prediction of successful induction of labor: Comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and the Bishop score. Eur J Ultrasound. 1998;7:183–7. doi: 10.1016/s0929-8266(98)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]