Abstract

Background:

Incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is twice as high as in Western countries. Prognostic factors for predicting function outcome and mortality play a major role in determining the treatment outcome.

Methods:

A prospective study of male and female patients ≥12 years with primary nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage were included. Hemorrhage caused by trauma, anticoagulant or thrombolytic drugs, brain tumor, saccular arterial aneurysm or vascular malformation were excluded. Functional outcome of patients was determined by modified Rankin's scale. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and ICH score were calculated for each patient.

Results:

Hypertension was present in 45 out of 49 patients (92%) with ICH of basal ganglia. Hypertension was significantly associated with worst clinical outcome. Mortality was high if the patient was comatose/stuporous compared to drowsy state (P < 0.0001). Mortality was found to be high when the size exceeded 30 cm3. High ICH score, low GCS score at the time of admission, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage, and midline shift were significantly associated with poor clinical outcome.

Conclusions:

Intracranial hemorrhage can be deleterious if present with low GCS score, high ICH score, intraventricular extension, and midline shift.

Keywords: Glasgow Coma Scale score, intracerebral hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage score, intracranial hemorrhage, Rankin score, stroke, Score de l’échelle de Coma de Glasgow, hémorragie intracérébrale, score d’hémorragie intracérébrale, hémorragie intracrânienne, score de Rankin, accident vasculaire cérébral

Résumé

Contexte:

Incidence de l’hémorragie intracérébrale (ICH) est deux fois plus élevé que dans les pays occidentaux. Les facteurs de pronostic pour prévoir de résultat de la fonction et de mortalité jouent un rôle majeur dans les résultats du traitement.

Méthodes:

Une étude prospective de patients masculins et féminins ≥12 ans avec primaire non traumatique intracrânienne l’hémorragie ont été inclus. Une hémorragie provoquée par un traumatisme, des médicaments anticoagulants ou thrombolytiques, tumeur au cerveau, anévrisme artériel sacculaire ou malformation vasculaire ont été exclus. Résultat fonctionnel des patients a été déterminé par l’échelle de Rankin modifiée. Score de Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) et ICH ont été calculés pour chaque patient.

Résultats:

L’hypertension était présente dans 45 sur 49 patients (92 %) avec ICH des noyaux gris centraux. L’hypertension a été associée significativement pire résultat clinique. La mortalité était élevée si le patient était dans le coma/stuporeux par rapport à l’état de somnolence (P < 0,0001). La mortalité s’est avérée pour être élevé lorsque la taille dépasse 30 cm3. ICH haute Il est élevé, le faible score de GCS au moment de l’admission, la présence de l’hémorragie intraventriculaire et décalage de la ligne médiane ont été significativement associés à mauvais pronostic clinique.

Conclusions:

Hémorragie intracrânienne peut être nocive s’il est présent avec le faible score de GCS, meilleur score de l’ICH, intraventriculaire extension et changement de la ligne médiane.

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a common devastating neurologic event that causes high morbidity and mortality with profound economic implication. ICH will seem to continue to be an important problem in both India and other developed countries. Nontraumatic ICH occurs due to bleeding from a vascular source directly into the brain substance. It is a major public health problem[1] with an annual incidence of 10–30/100,000 population,[1,2] accounting for 2 million (10–15%)[3] of about 15 million strokes worldwide each year.[4]

Approximately, 35–50% of patients with ICH die within the 1st month after bleeding.[5,6] Data from the Asian Stroke Advisory Panel revealed an incidence of ICH ranging from 17% to 33% of all strokes, twice as high as in Western countries.[7] Mortality depends on the size of the hematoma and on the location of the brain.

Intracranial hemorrhages include ICH, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). Hemorrhages occurring into extradural or subdural spaces are usually associated with trauma. Traumatic causes of hemorrhages were not included in present study. Primary or hypertensive (spontaneous) ICH, ruptured saccular aneurysm and vascular malformations and hemorrhages associated with bleeding disorders account for most of the hemorrhage that present as stroke.

Radiological studies such as computerized tomogram (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging have facilitated in locating and assessing the extent of insult precisely and deciding prognosis of the patient. Although several randomized therapeutic trials for ICH have been published, neither surgical nor medical treatments have been shown conclusively to benefit patients.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] However, early surgical intervention has shown mild statistically significant improvement in clinical outcome.[15] Prognostic factors for predicting function outcome and mortality thus play a major role in determining the treatment outcome.[5,6,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

Hospital admissions for ICH have increased by 18% in the past 10 years,[28] probably because of increases in the number of elderly people,[29] many of whom lack adequate blood pressure (BP) control, and the increasing use of anticoagulants, thrombolytics, and antiplatelet agents. Incidence might have decreased in some populations with improved access to medical care and BP control.[30,31,32]

Hence, we aimed to study, the clinical, radiological profile in patients of ICH. In clinical profile risk factors, symptomatology and physical findings were studied. In radiological profile, size, and location of hematomas, correlation of the size of hematomas with the short term prognosis (6 weeks) were also studied. We also studied mortality, morbidity, and predictive factors of clinical outcome of ICH.

Subjects and Methods

The study was started after obtaining approval from Institutional Review Board. The present study was conducted in the Medicine Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital in the Western part of India. Patients with intracranial hemorrhage during the period of November 2011–October 2013 were included. It is a prospective observational study. Hundred and nine patients with primary (nontraumatic) intracranial hemorrhage were included. Nine cases were excluded due to incomplete data. Male and females patients with age ≥12 years were included. Patients with intracranial hemorrhage (hemorrhage or bleeding within the skull) who have presented with a history of acute severe headache, altered sensorium, slurring of speech, acute hemiparesis, and accelerated hypertension – suggestive of acute cerebrovascular stroke and those who are presented with nontraumatic spontaneous hemorrhage were included. Patients whose hematoma was possibly caused by trauma, anticoagulant or thrombolytic drugs, brain tumor, saccular arterial aneurysm or vascular malformation were excluded. Patients with SAH, venous thrombosis, past history of intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and those who underwent surgical intervention for it were excluded.

All patients presenting with and fulfilling the inclusion criterion were included in this study after obtaining informed consents. Detailed relevant history and clinical examination were done according to predesigned and pretested protocol. All patients underwent CT imaging. Hematological and biochemical investigations like; complete blood counts, random blood sugar, renal function test, serum electrolytes, fasting serum lipid profile, prothrombin time with international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), two-dimensional (2D)-echocardiography with Doppler examination (2D echo), urine complete examination, ophthalmic fundus, and other investigations as and when required by standard laboratory techniques were done. The cases were studied in detail with emphasis on (1) contribution of risk factors particularly hypertension, (2) the level of consciousness on admission and improvement or deterioration thereafter and it's relation to prognosis, (3) the degree of motor weakness and mental functions and their recovery.

CT scan was done on admission in all patients to confirm the diagnosis of ICH and to correlate the prognosis with the CT scan features according to the size of the hematoma in cm3 (length × width × thickness/2 in cm3) at various locations.[16] Other parameters in the CT scan were also included viz., the presence of ventricular extension, presence of midline shift and inferences correlated with prognosis. Management during the hospital stay included control of hypertension with appropriate antihypertensives, treatment of raised intracranial pressure with mannitol, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, maintenance of airway, oropharyngeal suction, and Ryle's tube aspiration, general supportive measures to prevent bed sore, contractures. Treatment of intercurrent infections and associated complications were treated as per requirements. All the patients were followed up daily during the hospital stay and regularly thereafter until 6 weeks. Functional outcome of patients was determined by modified Rankin's scale (mRS).[33] Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and ICH score[16] were calculated for each patient.

Intracerebral hemorrhage score[16]

| Component | ICH score points |

|---|---|

| GCS score at presentation | |

| 13-15 | 0 |

| 5-12 | 1 |

| 3-4 | 2 |

| ICH volume (cm3) | |

| ≥30 | 1 |

| <30 | 0 |

| IVH | |

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Origin of ICH | |

| Infratentorial | 1 |

| Supratentorial | 0 |

| Age | |

| ≥80 | 1 |

| <80 | 0 |

| Total ICH score | 0-6 |

ICH=Intracerebral hemorrhage, IVH=Intraventricular hemorrhage, GCS=Glasgow Coma Scale

The data obtained was tabulated and was analyzed using proportion and percentages. Statistical Package for Social Science software (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for my statistical analysis. Different variables such as GCS score, ICH score, and its components, age, gender, BP, various risk factors of ICH were subjected to multiple regression analysis and were correlated with respect to clinical outcomes in term of mRS by GraphPad InStat software version 3.06 for Windows 95, (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com). Chi-square test was applied to calculate the mean value, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of mean value and P value of hematoma size of all groups.

Results

Total 109 cases were taken for the study, but nine patients have to be excluded from study data due to insufficient data. The following observations were made from the data.

Age and gender

The mean age of the patients was 55.15 years. The majority of them were between 40 and 65 years. However, increased age was not associated with an increase in mortality. There were 62 males and 38 females.

Risk factors

Hypertension

This is the most consistent risk factor for ICH. In the present study, 88 patients had a diastolic BP of >100 mmHg on admission (88%). Mean BP calculated was 118.51 mmHg. Hypertension was present in 45 out of 49 patients (92%) with ICH of basal ganglia. In the case of lobar hemorrhages, 15 out of the 21 patients (71%) had hypertension while in the case of thalamic hemorrhages 12 out of 14 patients (86%) had hypertension. All the patients with cerebellar and brainstem hemorrhages were found to be hypertensive.

Diabetes mellitus

This is one of the major risk factors contributing to stroke. Hyperglycemia predisposes to hyperlipidemia and atherogenesis and thus perpetuates hypertension. In this study, 10 patients gave past history of diabetes mellitus. Mean 2-h postprandial blood sugar (PP2 BS) value was 153.99 mg/dl.

Ischemic heart disease, smoking, alcohol and family history

Ischemic heart disease (IHD), smoking and alcohol abuse and family history of cerebrovascular accident have been observed to be associated with an increased incidence of ICH, but not to the extent of hypertension.

Clinical presentation

There was considerable overlap of clinical features between all forms of ICH though there are different clinical features for different sites, the incidence of hypertension on admission in all forms of ICH correlated with other features of hypertension like left ventricular hypertrophy with or without strain pattern in ECG and hypertensive retinopathy. A headache was present in 41% of the patients more commonly seen with lobar hemorrhages. Vomiting occurred in 39% of patients, and 17% had seizures at onset. In most of them, the seizures were generalized tonic-clonic in nature. There was no association between seizures and hematoma size. A headache, vomiting and altered level of consciousness were seen in many patients, but their absence did not rule out ICH.

Level of consciousness on admission

Altered level of consciousness is one of the most common manifestations of ICH. Its severity varies according to the size and location of the hematoma. Stupor or coma was a bad prognostic sign. Altered level of consciousness was present in 63 patients. Bilateral upper motor neuron (UMN) signs and absent Doll's eye movement was significantly associated with high mRS score.

Fundoscopy, chest X-ray and electrocardiogram

Evidence of hypertensive retinopathy was present in 25 patients. Out of which 16 patients were expired (60%) (P = 0.0007). Papillodema was present in two patients, both of them get expired. The presence of hypertensive retinopathy may suggest prolonged, and uncontrolled hypertension and hence may be associated with a poor prognosis. Commonest chest X-ray finding was cardiomegaly (51%). The most common ECG findings were left ventricular hypertrophy (48%) followed by ST-T changes (16%) and sinus bradycardia (6%).

Various factors and outcome relation

Mean BP calculated: 118.51 mmHg was subjected to regression analysis in relation to mRS. (A: mRS) = −5.817 + 0.079 × (B: Mean BP). R2 = 11.80%. This is the percent of the variance in mRS explained by mean BP. The P < 0.0001, which was considered extremely significant. So hypertension was significantly associated with worst clinical outcome. PP2 BS value was also subjected to regression analysis in relation to mRS, the P = 0.019, which was also clinically significant. Hence, hyperglycemia was also significantly associated with clinical outcome.

Mortality was high if the patient was comatose/stuporous compared to drowsy state (P < 0.0001). Impaired consciousness lasting for more than 48 h had a major impact on prognosis.

Other features of significance from the prognostic point of view are bilateral UMN signs indicate a poor prognosis. In this study, 17 out of the 21 patients (81%) with this finding expired (P < 0.0001). The absence of Doll's eye movement was associated with increased mortality (P = 0.007).

Computerized tomogram scan aspects and outcome relation

Following parameters were studied in CT scan brain, site of the hematoma, size of the hematoma, midline shift, and intraventricular extension/IVH.

Site of hematoma

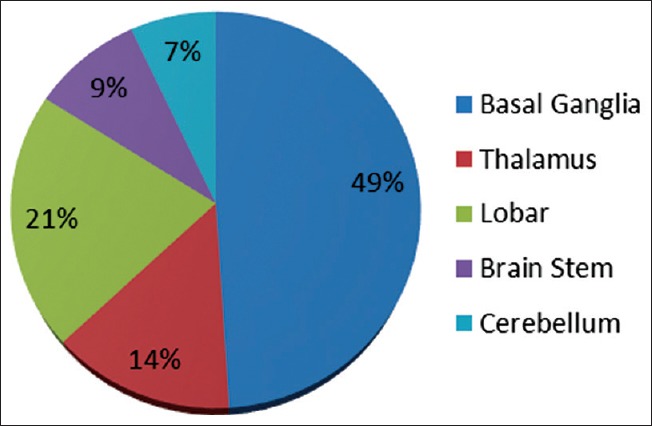

Most common site of ICH was basal ganglia (49%) followed by lobar (21%) and thalamus (14%). Mortality was 41% of all patients; it was highest in brain stem hematoma (67%) followed by a lobar hematoma (57%). Severe morbidity in term of mRS 4/5 was 15% in all patients; it was 21% in lobar, 14% in cerebellar, 14% in thalamus, 11% in the brainstem. IVH was highest in thalamus (43%) followed by lobar (38%) and basal ganglia (24%). Midline shift was highest in lobar (52%) and brainstem hematoma (44%) [Figure 1 and Table 1].

Figure 1.

Site of hematoma

Table 1.

Clinical outcomes, intraventricular hemorrhage and midline shift in relation to the location of intracranial hemorrhage

| Location | Mortality | Morbidity | IVH | Midline shift | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |

| All patients (n=100) | 41 | 41 | 15 | 15 | 27 | 27 | 34 | 34 |

| Basal ganglia (n=49) | 17 | 35 | 8 | 16 | 12 | 24 | 14 | 29 |

| Thalamus (n=14) | 8 | 57 | 2 | 14 | 6 | 43 | 5 | 36 |

| Lobar (n=21) | 6 | 29 | 3 | 21 | 8 | 38 | 11 | 52 |

| Brainstem (n=9) | 6 | 67 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 44 |

| Cerebellar (n=7) | 4 | 57 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

IVH=Intraventricular hemorrhage

Size of the hematoma versus prognosis in general

Overall mortality was 41%, and morbidity (mRS 3/4/5) was 15%. In the present study 39 patients had a hematoma size of ≤ 5 cm3, of which five patients (12.8%) died. One point which is worth noting is that all those five patients who died had brainstem hemorrhages. In the 5.1–15 cm3 group, out of the 22 patients four patients died (18.18%). Mortality rate was found to be high when the size exceeded 30 cm3 (24 out of 25, i.e., 96%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcome in relation to the size of the hematoma in general

| Size in cm3 | Cases (n) | Midline shift | Ventricular extension | Outcome (mRS) at 6 weeks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRS 1 | mRS 2 | mRS 3 | mRS 4 | mRS 5 | mRS 6 | Total | ||||

| <5 | 39 | 0 | 3 | 21 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 39 |

| 5.1-15 | 22 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 22 |

| 15.1-30 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 14 |

| >30 | 25 | 21 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 25 |

| Total | 100 | 34 | 27 | 24 | 20 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 41 | 100 |

The P value for mRS <3 versus mRS >3 is <0.0001. There is a significant linear trend among the ordered categories. mRS=Modified Rankin's scale

Clinical outcome in relation to size of intracerebral hemorrhage

Size of the ICH (cm3) was high in patients who died (n = 41, mean size 37.63 cm3, 95% CI: 30.47–44.79) compared to patients who survived (n = 59, mean size 6.98 cm3, 95% CI: 5.38–8.58) (P < 0.0001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Size of intracerebral hemorrhage and its mean value in relation to mortality

| Clinical outcome at 6 weeks | Number of patients | Mean value (cm3) | SDM | SEM | 95% CI of mean | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 100 | 19.55 | 21.56 | 2.16 | 15.23–23.87 | <0.0001 |

| Patients who died | 41 | 37.63 | 22.95 | 3.58 | 30.47–44.79 | |

| Patients who survived | 59 | 6.98 | 6.19 | 0.80 | 5.38–8.58 |

CI=Confidence interval, SEM=Standard error of mean, SDM=Standard deviation of mean

The size of the ICH was high in patients who had significant disability mRS >3 (n = 44, mean size 35.81 cm3, 95% CI: 28.80–42.81) compared to patients who had mild or no disability mRS ≤3 (n = 56, mean size 6.71 cm3, 95% CI: 5.09–8.33) (P < 0.0001). The increase in the size of ICH was significantly associated with increased mortality and poor clinical outcome in the present study. Other studies Nag et al. 2012,[34] Hemphill et al. 2009,[35] Hallevy et al. 2002,[36] Zia et al. 2009[37] and Broderick et al. 1993[25] shows similar results [Tables 4, Figure 2].

Table 4.

Size of intracerebral hemorrhage and its mean value in relation to clinical outcome (at 6 weeks) Modified Rankin's scale ≤3 and Modified Rankin's scale >3

| Clinical outcome at 6 weeks | Number of patient | Mean value (cm3) | SDM | SEM | 95% CI of mean | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 100 | 19.55 | 21.56 | 2.16 | 15.23-23.87 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with mRS <3 | 56 | 6.71 | 6.05 | 0.80 | 5.09-8.33 | |

| Patients with mRS >3 | 44 | 35.81 | 23.02 | 3.47 | 28.80-42.81 |

CI=Confidence interval, SEM=Standard error of mean, SDM=Standard deviation of mean, mRS=Modified Rankin's scale

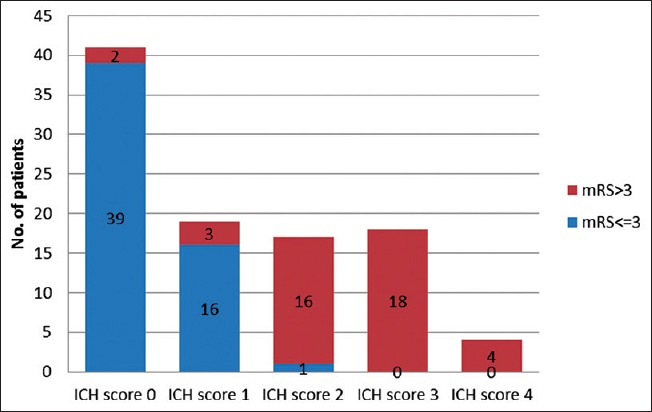

Figure 2.

Clinical outcome in relation to intracerebral hemorrhage score

Clinical outcome in relation to Glasgow Coma Scale score, intracerebral hemorrhage score, intraventricular hemorrhage, midline shift

Of all the 41 patients with ICH score 0, 39 had mRS <3, none died. Among 18 patients with ICH score 3, all patients died. All patients with ICH score 4 and 5 also died. The P value of mRS for ICH score is <0.0001 which is statistically highly significant. The increase in ICH score was associated with poor clinical outcome in the present study [Table 5].

Table 5.

Clinical outcome in relation to Glasgow Coma Scale score, intracerebral hemorrhage score, intraventricular hemorrhage, midline shift

| Number of patients | mRS <3 | mRS >3 | mRS 6 | χ2 |

P mRS <3 versus mRS >3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH score | ||||||

| 0 | 41 | 39 | 2 | 1 | 68.08 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 19 | 16 | 3 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 17 | 1 | 16 | 15 | ||

| 3 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 18 | ||

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 100 | 56 | 44 | 41 | ||

| GCS score | ||||||

| <8 | 36 | 1 | 35 | 34 | 61.33 | <0.0001 |

| >8 | 64 | 55 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Total | 100 | 56 | 44 | 41 | ||

| IVH | ||||||

| Present | 27 | 10 | 17 | 16 | 5.398 | <0.05 |

| Absent | 73 | 46 | 27 | 25 | ||

| Total | 100 | 56 | 44 | 41 | ||

| Midline shift | ||||||

| Present | 34 | 7 | 27 | 25 | 26.217 | <0.0001 |

| Absent | 66 | 49 | 17 | 16 | ||

| Total | 100 | 56 | 44 | 41 |

GCS=Glasgow Coma Scale, ICH=Intracerebral hemorrhage, IVH=Intraventricular hemorrhage, mRS=Modified Rankin's scale

Of all 100 patients, 36 patients had GCS score <8 at the time of admission, of which 35 had mRS score >3 and 34 died (P < 0.0001). IVH was present in 27 patients, of which 17 patients had mRS >3 and 16 died. 10 patients had mRS <3 [P = 0.005]. Midline shift was present in 34 patients of which 27 patients had mRS >3 and 25 were died (P < 0.0001).

Multiple regression analysis

With an objective to find out the impact of individual risk factor associated with higher mortality we have studied various variables such as age, size of ICH, mean BP, GCS score, ICH score, and they were subjected to multiple regression analysis in relation to clinical outcome in term of mRS score [Table 6].

Table 6.

Multiple regression analysis of different variable with mortality

| Variable | Beta coefficient | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.538 | 1.799 | 0.966-8.111 |

| A: Age | 0.014 | 0.012 | −0.011-0.038 |

| B: Mean BP | 0.003 | 0.012 | −0.020-0.026 |

| C: GCS score | −0.269 | 0.049 | −0.366-−0.172 |

| D: ICH score | 0.272 | 0.170 | −0.066-0.610 |

| F: Size | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.003-0.028 |

GCS=Glasgow Coma Scale, ICH=Intracerebral hemorrhage, CI=Confidence interval, SE=Standard error, BP=Blood pressure

Following results were obtained:

Estimated mortality = 4.538 + 0.014 × (A: Age) + 0.003 × (B: Mean BP) −0.269 × (C: GCS) + 0.272 × (D: ICH) + 0.015 × (F: Size).

Estimated mRS: 2.522 + 1.115 × (A: Age) + 0.258 × (B: Mean BP) −5.492 × (C: GCS) + 1.597 × (D: ICH) + 2.381 × (F: Size).

80.60% contribution in clinical outcome (mRS) at 6 weeks was made from five following variables: Age of the patient, mean BP control, the size of ICH, GCS score at admission and ICH score. That is to say, that size of ICH and GCS score at the time of admission were the most important predictor of clinical outcome [Table 7].

Table 7.

Which variable(s) make a significant contribution to outcome?

| Variable | Beta coefficient | P | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.522 | 0.013 | Yes |

| A: Age | 1.115 | 0.268 | No |

| B: Mean BP | 0.258 | 0.797 | No |

| C: GCS score | −5.492 | <0.0001 | Yes |

| D: ICH score | 1.597 | 0.114 | No |

| F: Size | 2.381 | 0.019 | Yes |

GCS=Glasgow Coma Scale, ICH=Intracerebral hemorrhage, BP=Blood pressure

Discussion

Age and gender

The incidence of ICH was highest in the age group 51–60 years (49% of the patients) in the present study. There was no significant gender difference observed. The distribution was similar to several other studies like Das Arjun study.[38]

Risk factors

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and ischemic heart disease

Hypertension was significantly associated with worst clinical outcome. Uncontrolled hypertension especially diastolic BP >100 mmHg was the most important risk factor in the present study. The majority of cases depending on the site of hemorrhage were associated with hypertension, especially cerebellar and brainstem hemorrhages. These findings were comparable to Das Arjun study.[38] Other factors, like left ventricular hypertrophy with or without strain pattern in ECG, hypertensive retinopathy indicated inadequately controlled hypertension were also with higher morbidity and mortality. Diabetes mellitus in our study was also a poor risk factor associated with worse clinical outcome. IHD, smoking, and alcohol abuse were less prominent risk factors in the present study.

Clinical presentation

Decreased level of consciousness on admission was associated with poor clinical outcome. The prognosis was worst in stuporous and comatose patients. Although symptoms such as a headache, vomiting, and altered level of consciousness were frequently seen, their absence did not rule out ICH with GCS <8.

The occurrence of a headache (41%), vomiting (39%), and seizures (17%) were comparable with other similar studies like Mohr[39] and Pillai study.[40] Mortality was high if the patient was comatose. It can be concluded that impaired consciousness lasting for more than 48 h had a major impact on prognosis which is also seen several other studies. Bilateral UMN signs indicate a poor prognosis (P < 0.0001). The absence of Doll's eye movement is associated with increased mortality (P = 0.007). The presence of hypertensive retinopathy may suggest prolonged, and uncontrolled hypertension and hence may be associated[41] with a poor prognosis.

Mortality, morbidity, and various parameters

The most common site for intracranial hemorrhage in the present study was basal ganglia (49%) followed by lobar (21%), thalamus (14%), brainstem (9%), and cerebellum (7%). These findings were comparable with several Indian studies except Das Arjun study[38] were basal ganglia, and thalamic hemorrhage was observed less than lobar, brain stem, and cerebellar hemorrhages. Prakash and Bhavani et al.[41,42] have similar sites of hemorrhage as our studies. The most important factors predicting the final outcome were the size of hematoma, intraventricular extension, midline shift, GCS score and ICH score. These results are comparable to results of an Indian study Nag et al. 2012[34] which also shows mean hematoma volume associated with death before 30 days is 33.16 cm3 (P < 0.0001), with survival after 30 days is 15.45 cm3 (P < 0.0001). Ventricular extension depends on the location of the hematoma, and the size and per se does not carry a poor prognosis with it. In the present study, out of total 27 patients having IVH, maximum IVH were associated with basal ganglia hemorrhages (44%). In the present study, 6 weeks outcome was good in patients with small hematoma ≤5 cm3 without midline shift or ventricular extension. Outcome worsened as the size of the hematoma increased. Mortality increased to 82% (32 out of 39 patients died) in patients having hematoma size >15 cm3. In the present study, mortality was higher in the case of brainstem hemorrhages (67%), followed by thalamic (57%) and cerebellar hemorrhages (57%).

The most important factors predicting the final outcome were the size of hematoma, intraventricular extension, midline shift, GCS score and ICH score. These results indicated that high ICH score, low GCS score at the time of admission, presence of IVH, and midline shift were significantly associated with poor clinical outcome. Our these results are comparable to other studies like Nag et al. 2012,[34] Hemphill et al. 2009,[35] Hallevy et al. 2002,[36] Zia et al. 2009[37] and Broderick et al. 1993.[25] Ventricular extension depends on the location of the hematoma and the size and per se does not carry a poor prognosis. In this study, out of total 27 patients having IVH, maximum IVH were associated with basal ganglia hemorrhages (12/27 = 44%).

However, surgical interventions early in the course of illness may change the course of illness. A small clinically relevant advantage has been noted by surgical trial in the intracerebral hemorrhage-II study when the early surgical intervention has been done in these cases of ICH.[15] However, the advantage may depend on surgical skill, infrastructure, and patient education. Timely surgical intervention may change outcome positively. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is also one of the risk factors for the development of ICH, which also need to be studied.

In the present study, 6 weeks outcome was good in patients with small hematoma ≤5 cm3 without midline shift or ventricular extension. Outcome worsened as the size of the hematoma increased. Mortality increased to 82% (32 out of 39 patients died) in patients having hematoma size >15 cm3. Mortality was relatively higher in the case of brainstem hemorrhages (67%), followed by thalamic (57%) and cerebellar hemorrhages (57%).

These results compared with other studies and according to these four predictors: GCS score, mRS, ICH score, and age were proposed as variables directly influencing hospital mortality in ICH.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1450–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labovitz DL, Halim A, Boden-Albala B, Hauser WA, Sacco RL. The incidence of deep and lobar intracerebral hemorrhage in whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Neurology. 2005;65:518–22. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172915.71933.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparable studies of the incidence of stroke and its pathological types: Results from an international collaboration. International stroke incidence collaboration. Stroke. 1997;28:491–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373:1632–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson OG, Lindgren A, Brandt L, Säveland H. Prediction of death in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage: A prospective study of a defined population. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:531–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.3.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poungvarin N, Viriyavejakul A. Spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haemorrhage: A prognostic study. J Med Assoc Thai. 1990;73:206–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroke epidemiological data of nine Asian countries. Asian acute stroke advisory panel (AASAP) J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM, Hope DT, et al. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the international surgical trial in intracerebral haemorrhage (STICH): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:387–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17826-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juvela S, Heiskanen O, Poranen A, Valtonen S, Kuurne T, Kaste M, et al. The treatment of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. A prospective randomized trial of surgical and conservative treatment. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:755–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.5.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auer LM, Deinsberger W, Niederkorn K, Gell G, Kleinert R, Schneider G, et al. Endoscopic surgery versus medical treatment for spontaneous intracerebral hematoma: A randomized study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:530–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.4.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hankey GJ, Hon C. Surgery for primary intracerebral hemorrhage: Is it safe and effective? A systematic review of case series and randomized trials. Stroke. 1997;28:2126–32. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batjer HH, Reisch JS, Allen BC, Plaizier LJ, Su CJ. Failure of surgery to improve outcome in hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage. A prospective randomized trial. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1103–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530100071015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuccarello M1, Brott T, Derex L, Kothari R, Sauerbeck L, Tew J, et al. Early surgical treatment for supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: A randomized feasibility study. Stroke. 1999;30:1833–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes HM, Gregson B, Siddique S, Mendelow AD. Surgery in intracerebral hemorrhage. The uncertainty continues. Stroke. 2000;31:2511–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Rowan EN, Murray GD, Gholkar A, Mitchell PM STICH II Investigators. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: A simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juvela S. Risk factors for impaired outcome after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1193–200. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540360071018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampl Y, Gilad R, Eshel Y, Sarova-Pinhas I. Neurological and functional outcome in patients with supratentorial hemorrhages. A prospective study. Stroke. 1995;26:2249–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.12.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lisk DR, Pasteur W, Rhoades H, Putnam RD, Grotta JC. Early presentation of hemispheric intracerebral hemorrhage: Prediction of outcome and guidelines for treatment allocation. Neurology. 1994;44:133–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung RT, Zou LY. Use of the original, modified, or new intracerebral hemorrhage score to predict mortality and morbidity after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:1717–22. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000078657.22835.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daverat P, Castel JP, Dartigues JF, Orgogozo JM. Death and functional outcome after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. A prospective study of 166 cases using multivariate analysis. Stroke. 1991;22:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razzaq AA, Hussain R. Determinants of 30-day mortality of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in Pakistan. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:336–42. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(98)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermeer SE, Algra A, Franke CL, Koudstaal PJ, Rinkel GJ. Long-term prognosis after recovery from primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2002;59:205–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuhrim S, Dambrosia JM, Price TR, Mohr JP, Wolf PA, Hier DB, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage: External validation and extension of a model for prediction of 30-day survival. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:658–63. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–93. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer SA, Sacco RL, Shi T, Mohr JP. Neurologic deterioration in noncomatose patients with supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 1994;44:1379–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.8.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuhrim S, Horowitz DR, Sacher M, Godbold JH. Volume of ventricular blood is an important determinant of outcome in supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:617–21. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Nasar A, Kirmani JF, Ezzeddine MA, Divani AA, et al. Changes in cost and outcome among US patients with stroke hospitalized in 1990 to 1991 and those hospitalized in 2000 to 2001. Stroke. 2007;38:2180–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.467506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Anderson CS. Stroke epidemiology: A review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubo M, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Tanizaki Y, Arima H, Tanaka K, et al. Trends in the incidence, mortality, and survival rate of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese community: The Hisayama study. Stroke. 2003;34:2349–54. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000090348.52943.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang B, Wang WZ, Chen H, Hong Z, Yang QD, Wu SP, et al. Incidence and trends of stroke and its subtypes in China: Results from three large cities. Stroke. 2006;37:63–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000194955.34820.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, Howard SC, Silver LE, Bull LM, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study) Lancet. 2004;363:1925–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19:1497–500. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nag C, Das K, Ghosh M, Khandakar MR. Prediction of clinical outcome in acute hemorrhagic stroke from a single CT scan on admission. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:463–7. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.101986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Farrant M, Neill TA., Jr Prospective validation of the ICH Score for 12-month functional outcome. Neurology. 2009;73:1088–94. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b8b332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallevy C, Ifergane G, Kordysh E, Herishanu Y. Spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Criteria for short-term functional outcome prediction. J Neurol. 2002;249:1704–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0911-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zia E, Engström G, Svensson PJ, Norrving B, Pessah-Rasmussen H. Three-year survival and stroke recurrence rates in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3567–73. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gobindram A. Stroke care: Experiences and clinical research in stroke units in Chennai. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2006;9:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohr JP, Caplan LR, Melski JW, Goldstein RJ, Duncan GW, Kistler JP, et al. The Harvard Cooperative Stroke Registry a prospective registry. Neurology. 1978;28:754–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pillai AM. Experience with spontaneous intracerebral haematomas. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 1988;86:233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhavani G. prognosis of hypertensive ICH, clinical and radiological correlates. 37th annual Neurological Congress of India. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prakash G. Gupta. The usefulness of clinical features and CT in the treatment of intracerebral hematomas. Neuro India. 1986;34:47–52. [Google Scholar]