Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The increasing frequency of cardiovascular disease (CVD) rests on the presence of major cardiovascular risk factors including dyslipidemia. This dyslipidemia is also a target for the prevention and treatment of many cardiovascular diseases. Hence, identification of individuals at risk of CVD is needed for early identification and prevention. The study was carried out to evaluate dyslipidemia using the lipid ratios and indices instead of just the conventional lipid profile.

Methodology:

It was a cross-sectional study with 699 participants recruited from semi-urban communities in Nigeria. Anthropometric indices, blood pressure, and fasting lipid profiles were determined. Abnormalities in lipid indices and lipid ratios with atherogenic index were also determined. SPSS software version 17.0 were used for analysis, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

There were 699 participants with a mean age of 64.45 ± 15.53 years. Elevated total cholesterol, high low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, elevated triglyceride, and low high-density lipoprotein were seen in 5.3%, 19.3%, 4.4%, and 76.3% of the participants, respectively. The Castelli's risk index-I (CRI-I) predicted the highest prevalence of predisposition to cardiovascular risk (47.8%) with females being at significantly higher risk (55.2% vs. 29.3%, P < 0.001). Atherogenic coefficient, CRI-II, CHOLIndex, atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) predicted a cardiovascular risk prevalence of 22.5%, 15.9%, 11.2%, and 11.0%, respectively, with no significant difference in between the sexes.

Conclusions:

Serum lipid ratios and AIP may be used in addition to lipid parameters in clinical practice to assess cardiovascular risks even when lipid profiles are apparently normal. AIP was more gender specific amidst the lipid ratios.

Keywords: Atherogenic index of plasma, coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia, lipid ratios, Nigeria, Indice athérogène du plasma, maladie coronarienne, dyslipidémie, taux de lipides, Nigeria

Résumé

Contexte et Objectifs:

La fréquence croissante des maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) repose sur la présence de facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires majeurs, y compr is la dyslipidémie. Cette dyslipidémie est également une cible pour la prévention et le traitement de nombreuses maladies cardiovasculaires. Par conséquent, l’identification des personnes à risque de maladie cardiovasculaire est nécessaire pour l’identification précoce et la prévention. L’étude a été réalisée pour évaluer la dyslipidémie en utilisant les derniers rapports et index au lieu du profil lipidique conventionnel.

Méthodologie:

Il s’agissait d’une étude transversale avec 699 participants recrutés dans des communautés semiurbaines au Nigeria. Les indices anthropométriques, la pression artérielle et les profils lipidiques à jeun ont été déterminés. Des anomalies des indices lipidiques et des rapports lipidiques avec indice athérogène ont également été déterminées. Le logiciel SPSS version 17.0 a été utilisé pour l’analyse, P < 0.05 a été considéré comme statistiquement significatif.

Résultats:

Il y avait 699 participants avec un âge moyen de 64,45 ± 15,53 ans. Le taux de cholestérol total élevé, le taux élevé de lipoprotéines de faible densité, le taux élevé de triglycérides et de lipoprotéines de haute densité ont été observés chez respectivement 5,3%, 19,3%, 4,4% et 76,3% des participants. L’indice de risque I de Castelli (CRI-I) prédisait la prévalence la plus élevée de prédisposition au risque cardiovasculaire (47,8%), les femmes étant significativement plus à risque (55,2% vs 29,3%, P < 0,001). Le coefficient athérogène, CRI-II, CHOLIndex, l’indice athérogène du plasma (AIP) prédisait une prévalence du risque cardiovasculaire de 22,5%, 15,9%, 11,2% et 11,0%, respectivement, sans différence significative entre les sexes.

Conclusions:

Les rapports lipidiques sériques et l’AIP peuvent être utilisés en plus des paramètres lipidiques dans la pratique clinique pour évaluer les risques cardiovasculaires même lorsque les profils lipidiques sont apparemment normaux. L’AIP était plus spécifique au sexe parmi les ratios lipidiques.

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is a single strong risk factor for the development of future cardiovascular events in the population such as stroke, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease.[1,2] It has been described as a disease of the economically advanced societies, but in recent times, it has been discovered to find its way into the semi-urban societies among its dwellers, who are at the increasing risk of developing future cardiovascular events.[3] Hence, early identification and diagnosis of dyslipidemia at its earliest stage before the onset of cardiovascular events among this populace is a worthwhile cardiovascular preventive measure.[4,5]

In the evaluation of dyslipidemia, triglycerides (TGs), low-density lipoproteins-cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoproteins-cholesterol (HDL-C), and total cholesterol (TC) are the lipid profiles that are commonly considered, with emphasis majorly on LDL-C as “bad lipoprotein.”[6] We were trying to say using either LDL-C alone or HDL-C alone is inadequate for te prediction of cardiovascular risk, especially in individuals with intermediate risk.[7,8]

Studies have, however, demonstrated that in times when the conventional lipid parameters (TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TC) remain apparently normal, lipid ratios such as the Castelli's risk index-I (CRI-I), CRI-II, atherogenic coeefficient (AC), CHOLIndex, and the atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) are the diagnostic alternatives that have been shown in predicting the risk of developing cardiovascular events[9,10,11,12] and effectiveness of therapy.[13] CRI-I (also known as cardiac risk ratio [CRR]) has been particularly shown to reflect coronary plaques formation and the thickness of intima-media in the carotid arteries of young adults.[14,15] CHOLIndex is a relatively new simple index that has been demonstrated to predict the likelihood of developing coronary arterial disease (CAD) with more accuracy than the other lipid ratios.[11]

The evaluation of cardiovascular risk in the Sub-Saharan African population has used some cardiovascular risk scoring systems such as the Framingham risk score, conventional lipid profile, and few lipid ratios.[16,17] Hence, the present study is aimed at evaluating dyslipidemia in semi-urban communities using the lipid profiles, lipid ratios, and AIP as estimates of cardiovascular risk.

Methodology

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional study that was carried out in Ekiti State located in Southwestern Nigeria. The participants in this study were members of semi-urban communities and they were mostly Yoruba speaking from five local government areas. Those selected for inclusion into the study were adults who were at least 18 years old and voluntarily consented. Exclusion criteria included pregnant women, those with features suggestive of organ failures such as heart or kidney failures or with acute illness. In addition, those who did not come fasting or declined consent were excluded from the study. The clinical evaluation was done over a period of 6 months at designated screening centers in the communities with prior notices obtained from traditional rulers, opinion leaders, church leaders, and mosque leaders.

Blood tests

Fasting blood samples (3 ml) were collected by venopuncture from the antecubital vein, into sterile plain bottles, under aseptic conditions (participants were already informed of fasting state and this was further ascertained at the point of sample collection). The blood samples were allowed to clot and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Serum was stored frozen at −20°C, and analysis was carried out within 1 week of sample collection. The serum was used for blood chemistry analysis – TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and TGs. The TC and the different cholesterol fractions were determined using commercially available reagent (Randox® laboratories Ltd., UK).[18] The concentration of LDL-C was determined using the Friedewald equation for participants with a TG <4.5 mmol/L.[19] Blood sugar was done with ACCU-CHEK® glucometer (Roche Diagnostics GmBH, Sandhofer Strasse 116, 68305 Mannheim, Germany), the measuring range of the device for glucose is 50–600 mg/dl. All samples were analyzed at the chemical pathology department, Federal Medical Centre, Ido-Ekiti.

Lipids, atherogenic index, and lipid ratio evaluation

Lipid abnormality was defined as raised when TG level ≥1.7 mmol/L, reduced HDL-C - <1.03 mmol/L in males and <1.30 mmol/L in females, and TC level ≥5.2 mmol/L (200 mg/dl).[20]

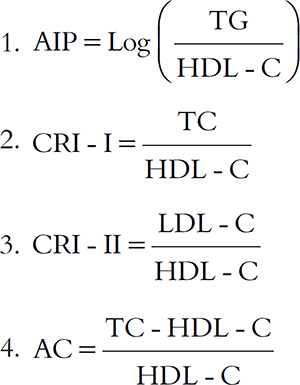

The atherogenic index and lipid ratios were calculated using the following established formulas:[10,21]

5. CHOLIndex = LDL-C − HDL-C (TG <400) = LDL-C – HDL-C + 1/5 TG (TG >400).

The following are the abnormal values of AIP, lipid ratios, and CHOLIndex for cardiovascular risk: AIP >0.1, CRI-I >3.5 in males and >3.0 in females, CRI-II >3.3, AC >3.0, and CHOLIndex >2.07.[10,11,22,23]

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Federal Medical Centre, Ido-Ekiti.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered into the computer and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, v 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables are presented as percentages. Sociodemographic variables as well as all continuous variables were expressed as either means ± standard deviation or mean ± standard error of mean. Differences between two means were assessed using Student's t-test while Chi-square test was used to assess the degree of association of categorical variables with Fisher's exact test applied appropriately. All P values were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study had a total of 699 participants aged 30 years and above with the mean age of 64.23 ± 16.41 years and 64.53 ± 15.18 years for males and the females, respectively. The BMI, waist circumference (WC), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose of the participants are shown in Table 1. The WC in females was significantly higher than that of males (83.92 vs. 87.13, P = 0.001), while the other clinical parameters were nonsignificantly higher in males apart from the blood pressures.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the population

| Variable | Mean±SD | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | ||

| Age (years) | 64.45±15.53 | 64.23±16.41 | 64.53±15.18 | 0.817 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.22±16.77 | 24.65±27.99 | 24.05±9.16 | 0.672 |

| WC (cm) | 86.22±11.93 | 83.92±9.60 | 87.13±12.63 | 0.001* |

| SBP (mmHg) | 143.42±28.95 | 143.27±29.67 | 143.47±28.69 | 0.935 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 82.23±14.18 | 82.06±15.07 | 82.29±13.83 | 0.847 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.52±1.90 | 5.59±1.95 | 5.49±1.88 | 0.644 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.17±1.09 | 3.06±0.98 | 3.21±1.13 | 0.112 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.03±0.48 | 1.09±0.55 | 1.01±0.46 | 0.057 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.81±0.99 | 1.75±1.09 | 1.83±0.95 | 0.321 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.80±0.48 | 0.75±0.34 | 0.82±0.52 | 0.082 |

*Significant. BMI=Body mass index, WC=Waist circumference, SBP=Systolic blood pressure, DBP=Diastolic blood pressure, TC=Total cholesterol, HDL-C=High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C=Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG=Triglycerides, SD=Standard deviation

In the population, the average TC, LDL-C, and TG were higher in females compared to males (3.21 vs. 3.06, P = 0.112; 1.83 vs. 1.75, P = 0.321; and 0.82 vs. 0.75, P = 0.082, respectively). On the other hand, HDL-C was higher in males than females (P = 0.057) with the combined average being 1.03 ± 0.48 as shown in Table 1.

Table 2 shows that 533 participants (76.3%) had low HDL-C, 37 (5.3%) had elevated TC, 135 (19.3%) had elevated LDL-C, and 31 (4.4%) had elevated TG. The low HDL-C and elevated TG were significantly higher in the female participants than in the males (83.4% vs. 51.8%, P = <0.001; 5.6% vs. 1.5%, P = 0.011) while there was no significant difference in other dyslipidemias in between the sexes.

Table 2.

Dyslipidemia among the study population

| Variable | Total (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated TC | 37 (5.3) | 6 (3.0) | 31 (6.2) | 0.063 |

| Low HDL-C | 533 (76.3) | 115 (51.8) | 418 (83.4) | <0.001* |

| Elevated LDL-C | 135 (19.3) | 36 (18.2) | 99 (19.8) | 0.359 |

| Elevated TG | 31 (4.4) | 3 (1.5) | 28 (5.6) | 0.011* |

*Significant. TC=Total cholesterol, HDL-C=High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C=Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG=Triglycerides

Across all the participants, the mean of the AIP was 0.06 ± 0.002, CRI-I was 3.76 ± 0.10, CRI-II was 2.32 ± 0.09, AC was 2.76 ± 0.10, and CHOLIndex was 0.78 ± 0.04 mmol/L [Table 3]. There was no significant difference in the atherogenic index and lipid ratios in between the sexes. All the lipid ratios are slightly higher in females than in males except the AIP where the values are almost the same for both sexes.

Table 3.

The distribution of atherogenic index and lipid ratios among the study population

| Indices | Mean±SEM | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | ||

| AIP | 0.06±0.002 | 0.06±0.003 | 0.06±0.002 | 0.433 |

| CRI | ||||

| I | 3.76±0.10 | 3.60±0.19 | 3.83±0.11 | 0.286 |

| II | 2.32±0.09 | 2.28±0.18 | 2.34±0.10 | 0.763 |

| AC | 2.76±0.10 | 2.60±0.19 | 2.83±0.11 | 0.286 |

| CHOLIndex (mmol/L) | 0.78±0.04 | 0.66±0.09 | 0.82±0.05 | 0.080 |

AIP=Atherogenic index of plasma, CRI=Castelli’s risk index, AC=Atherogenic coefficient, SEM=Standard error of mean

The CRI-I predicted the highest prevalence of predisposition to cardiovascular risk (47.8%) with females being at significantly higher risk (55.2% vs. 29.3%, P < 0.001). AC, CRI-II, CHOLIndex, and AIP predicted a cardiovascular risk prevalence of 22.5%, 15.9%, 11.2%, and 11.0%, respectively, with no significant difference in between the sexes [Table 4].

Table 4.

Distribution of abnormal lipid ratios among the study population

| Indices | Total (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIP | 77 (11.0) | 23 (11.6) | 54 (10.8) | 0.750 |

| CRI | ||||

| I | 333 (47.8) | 58 (29.3) | 275 (55.2) | <0.001* |

| II | 111 (15.9) | 27 (13.6) | 84 (16.8) | 0.308 |

| AC | 156 (22.5) | 36 (18.4) | 120 (24.1) | 0.104 |

| CHOLIndex | 78 (11.2) | 20 (10.1) | 58 (11.6) | 0.577 |

*Significant. AIP=Atherogenic index of plasma, CRI=Castelli’s risk index, AC=Atherogenic coefficient

Discussion

This study had examined and evaluated the lipid abnormalities, atherogenic indexes, and lipid ratios among semi-urban dwellers as a predictor of risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). The participants in this study were predominantly females as were in cross-sectional studies.[24] In this study, low HDL-C has the highest prevalence as an indicator of dyslipidemia while elevated TC and TG were particularly low among the participants. Low HDL-C has been reported to be high (60%, 53%, and 58.9%, respectively) in studies[25,26,27] among urban dwellers. The high prevalence of 76.3% observed in this study further reiterates the fact that dyslipidemia is no longer an “Urban” disease. LDL-C level, which is the primary target for drug intervention according to the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, is relatively low in this study when compared with a similar study[25] although similar to 18.6% obtained by Okaka and Eiya[28] in a rural community. The lipid profile averages fall in the same range and agree with previous findings that the plasma cholesterol levels in Nigeria are less than in the developed countries.[29,30,31,32]

Judging with low HDL-C, dyslipidemia was present in a reasonable majority of the females much more than males, although when considering both sexes there is a high proportion of low HDL-C as reflected in the total value. Low HDL-C has been focused as an independent major predictor of future cardiovascular events in individuals[33] and although the serum levels of other lipids seem not too disturbed as seen in our study, further analysis using lipid ratios brought out the true picture.

The average AIP in this study is lower than the recommended value of 0.1. AIP which is a logarithm of the ratio of TG to HDL-C takes into consideration the balance between atherogenic and protective lipids and may be very useful, especially in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. It puts the risk of CVDs at 11.0% for the total population; this is more than for low HDL-C. This suggests that considering low HDL alone for risk of CVDs can be exaggerative of the true picture. The average AIP gotten for the population is close to 0.08 and 0.10 reported by Adediran et al. for rural and urban dwellers, respectively, in a Nigerian study,[34] and also 0.09 reported in an Indian population.[11]

CRI-I, also called CRR, showed the highest risk of 47.8% for developing CVDs amidst the indexes and ratios, demonstrating a significant difference in the risk between the sexes. Knowing it is HDL-C dependent as is all the ratios, it is the only ratio that has HDL in both the numerator and denominator, and it is not surprising to have it relatively high just as the proportion of abnormal HDL-C is high.

Conclusions

Dyslipidemia is not an uncommon feature in adult Nigerians in the semi-urban communities. Our study supports the finding that elevated level of low HDL-C, elevated TC, LDL-C, and TG may not be restricted to those in urban societies. These lipid abnormalities appear to be more pronounced as indicated by raised lipid ratios and atherogenic indexes. These lipid ratios and atherogenic indexes could be used for individuals at higher risk of CVD among Nigerian population on the clinical setting, especially when the absolute values of individual lipid profiles seem normal. Thus, the use of these indices should be encouraged to detect abnormal lipid profiles to identify individuals at increased risks of cardiovascular risk disease including CAD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rached FH, Chapman MJ, Kontush A. An overview of the new frontiers in the treatment of atherogenic dyslipidemias. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96:57–63. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, Albus C, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012).The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. Doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. Epub 2012 May 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okafor CI. The metabolic syndrome in Africa: Current trends. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:56–66. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Williams K, Neely B, Sniderman AD, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1422–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirimarco G, Labreuche J, Bruckert E, Goldstein LB, Fox KM, Rothwell PM, et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia and residual cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients. Stroke. 2014;45:1429–36. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Superko HR, King S., 3rd Lipid management to reduce cardiovascular risk: A new strategy is required. Circulation. 2008;117:560–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.667428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD. Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: The St. Francis Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Criqui MH, Golomb BA. Epidemiologic aspects of lipid abnormalities. Am J Med. 1998;105:48S–57S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akpinar O, Bozkurt A, Acartürk E, Seydaoglu G. A new index (CHOLINDEX) in detecting coronary artery disease risk. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2013;13:315–9. doi: 10.5152/akd.2013.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhardwaj S, Bhattacharjee J, Bhatnagar MK, Tyagi S. Atherogenic index of plasma, Castelli risk index and atherogenic coefficient- new parameters in assessing cardiovascular risk. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2013;3:359–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nwagha UI, Ikekpeazu EJ, Ejezie FE, Neboh EE, Maduka IC. Atherogenic index of plasma as useful predictor of cardiovascular risk among postmenopausal women in Enugu, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:248–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobiásová M, Frohlich J, Sedová M, Cheung MC, Brown BG. Cholesterol esterification and atherogenic index of plasma correlate with lipoprotein size and findings on coronary angiography. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:566–71. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P011668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair D, Carrigan TP, Curtin RJ, Popovic ZB, Kuzmiak S, Schoenhagen P, et al. Association of total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with proximal coronary atherosclerosis detected by multislice computed tomography. Prev Cardiol. 2009;12:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2008.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frontini MG, Srinivasan SR, Xu JH, Tang R, Bond MG, Berenson G. Utility of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol versus other lipoprotein measures in detecting subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults (The Bogalusa Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girish M, Raghunandana R, Kumar K, Basawaraj C. A cross sectional study of serum gamaglutamyl transferase acitivity with reference to atherogenic lipid indices in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3:2655–62. DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2188. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobiásová M. AIP – Atherogenic index of plasma as a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk: From research to practice. Vnitr Lek. 2006;52:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiruvelan. Cholesteroal Ratios. [Last updated on 2014 May 04; Last cited on 2015 Dec 09]. Available from: http://www.healthy-ojas.com/cholesterol/cholesterol-ratios.html .

- 20.Wahab KW, Sani MU, Yusuf BO, Gbadamosi M, Gbadamosi A, Yandutse MI. Prevalence and determinants of obesity – A cross-sectional study of an adult Northern Nigerian population. Int Arch Med. 2011;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oguejiofor OC, Onwukwe CH, Odenigbo CU. Dyslipidemia in Nigeria: Prevalence and pattern. Ann Afr Med. 2012;11:197–202. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.102846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogbera AO, Fasanmade OA, Chinenye S, Akinlade A. Characterization of lipid parameters in diabetes mellitus – A Nigerian report. Int Arch Med. 2009;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogunleye OO, Ogundele SO, Akinyemi JO, Ogbera AO. Clustering of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia in a Nigerian population: A cross sectional study. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2012;41:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okaka EI, Eiya BO. Prevalence and pattern of dyslipidemia in a rural community in Southern Nigeria. Afr J Med Health Sci. 2013;12:82–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glew RH, Kassam HA, Bhanji RA, Okorodudu A, VanderJagt DJ. Serum lipid profiles and risk of cardiovascular disease in three different male populations in northern Nigeria. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20:166–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ademuyiwa O, Ugbaja RN, Rotimi SO. Plasma lipid profile, atherogenic and coronary risk indices in some residents of Abeokuta in South-Western Nigeria. Biokemistri. 2008;20:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tóth PP, Potter D, Ming EE. Prevalence of lipid abnormalities in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2006. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheidt-Nave C, Du Y, Knopf H, Schienkiewitz A, Ziese T, Nowossadeck E, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among adults in Germany: Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS 1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:661–7. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toth PP. High-density lipoprotein and cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2004;109:1809–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126889.97626.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adediran OS, Akintunde AA, Opadijo OG, Araoye MA. Dyslipidaemia, atherogenic index and urbanization in central Nigeria: Associations, impact, and a call for concerted action. Int J Cardiovasc Res. 2013;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tóth PP, Potter D, Ming EE. Prevalence of lipid abnormalities in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2006. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.05.002. Doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.05.002. Epub 2012 May 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheidt-Nave C, Du Y, Knopf H, Schienkiewitz A, Ziese T, Nowossadeck E, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among adults in Germany: Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS 1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:661–7. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1670-0. Doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toth PP. High-Density Lipoprotein and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2004;109:1809–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126889.97626.B8. Doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126889.97626.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adediran OS, Akintunde AA, Opadijo OG, Araoye MA. Dyslipidaemia, Atherogenic Index and Urbanization in Central Nigeria: Associations, Impact, and a Call for Concerted Action. Int J Cardiovasc Res. 2013;2:4. [Google Scholar]