Abstract

Introduction:

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adult (LADA) is a form of Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) that occurs in adult or with advancing age. It commonly occurs in people aged ≥30 years and is characterized by initial response to oral hypoglycemic agents, lean body mass, and presence of glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody (GAD-Ab). It exhibits rapid deterioration of the pancreatic β-cells secretory function due to the destructive action of the autoantibodies. The prevalence of LADA among T2DM patients varies among population due to different diagnostic criteria, patients’ characteristics, the assay used, and genetic predisposition. In this study, we intend to document prevalence and clinical characteristics of LADA subset patients in Northern Nigeria.

Methods:

Two-hundred noninsulin-requiring T2DM patients were recruited from the diabetes clinic based on the selection criteria. Their clinical characteristics were documented, and we measured their serum GAD-Ab, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting C-peptide, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting serum lipids. The mean (standard deviation) of these clinical and biochemical parameters was compared between GAD-Ab+ and GAD-Ab− groups. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 with P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results:

The prevalence of LADA among the T2DM patients studied was found to be 10.5% (21/200); there were more males than females (15 [71%]:6 [29%], χ2 = 4.2, P < 0.05). The mean age of the GAD-Ab+ was 52.0 (11.0), and there was no statistical difference with GAD-Ab− group. GAD-Ab+ was found more common in the age group of 40–49 years 10/21 (48%). The body mass index, waist circumference, and serum C-peptide were found to be significantly lower in GAD-Ab+ than in GAD-Ab− group (22.1 [51], 80.1 [12.4], 0.84 [0.05] vs. 27.3 [4.9], 93.2 [10.9], 1.72 [0.43]), P < 0.05. The HbA1c was found to be significantly higher in GAD-Ab+ than in GAD-Ab− (8.3 [1.4] vs. 7.0 [2.1]). Other clinical and metabolic parameters were found not to be significantly different between the two groups.

Conclusion:

We conclude that the prevalence of LADA among T2DM patients in Northern Nigeria is 10.5%. It is more common among males aged 40–49 years and lean subjects. The male sex and decreasing central adiposity are predictors of GAD-Ab+ among T2DM subjects.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody, latent autoimmune diabetes in adult, Nigeria, prevalence, Diabète sucré, l’anticorps acide glutamique décarboxylase, le diabète auto-immune latente chez l’adulte, le Nigeria, la prévalence

Résumé

Introduction:

le diabète auto-immune latente chez l’adulte (LADA) est une forme de diabète de type 1 (DT1) qui se produit chez l’adulte ou avec l’âge. Il se produit généralement chez les personnes âgées de ≥30 ans et se caractérise par la réponse initiale aux hypoglycémiants oraux, la masse corporelle maigre, et la présence de glutamique décarboxylase d’acide autoanticorps (GAD-Ab). Il présente une détérioration rapide de la fonction de sécrétion des cellules ß pancréatiques en raison de l’action destructrice des auto-anticorps. La prévalence de la LADA chez les patients atteints de DT2 varie parmi la population en raison de différents critères de diagnostic, les caractéristiques des patients, le test utilisé, et la prédisposition génétique. Dans cette étude, nous avons l’intention de documenter les caractéristiques de prévalence et cliniques des patients sous-ensemble LADA dans le nord du Nigeria.

Méthodes:

Deux cent patients atteints de DT2 non insulino-nécessitant ont été recrutés dans la clinique du diabète sur la base des critères de sélection. Leurs caractéristiques cliniques ont été documentés, et nous avons mesuré leur sérum GAD-Ab, l’hémoglobine glyquée (HbA1c), le jeûne C-peptide, la glycémie à jeun, et les lipides sériques à jeun. La moyenne (écart-type) de ces paramètres cliniques et biochimiques a été comparée entre GAD-Ab + et les groupes GAD-Ab-. Les données ont été analysées à l’aide du logiciel SPSS version 20 avec P < 0,05 comme statistiquement significative.

Résultats:

La prévalence de la LADA parmi les patients atteints de DT2 étudié a été trouvé à 10,5% (21/200); il y avait plus d’hommes que de femmes (15 [71%]: 6 [29%], χ2 = 4,2, P < 0,05). L’âge moyen du GAD-Ab + était de 52,0 (11,0), et il n’y avait pas de différence statistique avec le groupe GAD-Ab-. GAD-Ab + a été trouvé plus fréquents dans le groupe des 40-49 ans 10/21 (48%) d’âge. L’indice de masse corporelle, le tour de taille, et le sérum C-peptide se sont avérés significativement plus faible dans GAD-Ab + que dans le groupe-Ab- GAD (22,1 [51], 80.1 [12.4], 0,84 [0,05] vs. 27.3 [4.9 ] 93,2 [10,9] 1,72 [0,43]), P < 0,05. L’HbA1c a été jugée significativement plus élevée dans GADAb + que dans GAD-Ab- (8.3 [1.4] vs. 7.0 [2.1]). D’autres paramètres cliniques et métaboliques ont été trouvés ne pas être significativement différente entre les deux groupes.

Conclusion:

Nous concluons que la prévalence de la LADA chez les patients atteints de DT2 dans le nord du Nigeria est de 10,5%. Il est plus fréquent chez les hommes âgés de 40-49 ans et les sujets maigres. Le sexe masculin et la diminution de l’adiposité centrale sont des prédicteurs de GAD-Ab + chez les sujets atteints de DT2.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion or a reduction in the biologic effectiveness of insulin (or both).[1] It is associated with acute complications such as ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar state, and hypoglycemia, as well as long-term complications affecting the eyes, kidneys, feet, brain, heart, nerves, and blood vessels. DM is broadly classified into Type 1 DM (T1DM) which occurs as a result of absolute insulin deficiency and T2DM; the predominant form of diabetes (>90%) is characterized by relative insulin deficiency or resistance.[1,2]

Type 1A diabetes is caused by autoimmune destruction of the pancreatic β-cells, thereby leading to absolute insulin deficiency and subsequent dependency on insulin in most patients.[3] The pancreatic autoantibodies implicated in the autoimmune process include glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody (GAD-Ab), islet cell cytoplasmic antibody (ICA), and antibodies to the protein tyrosine phosphatases Islet antibody (IA2 or IA2-β). The GAD-Ab, which is more sensitive and higher concentration in adult population, is used to diagnose Type 1A diabetes (T1A) among adult patients.[2,4,5]

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) is a form of TIA diabetes that occurs late and can be mistaken as a T2DM. It is characterized by age usually >30 years, lean body mass, insulin independence within the first 6 months of diagnosis, positive GAD-Ab, and low serum C-peptide level.[6,7,8,9] LADA shared both features of T1DM: presence of autoantibody (GAD-Ab), decreased body mass index (BMI), and less C-peptide and T2DM characteristics of late-onset and insulin resistance.[7,8,10] It has been found that the LADA subset of patients has similar or even higher genetic predisposition to develop nonimmune diabetes as compared to those GAD-Ab− diabetes.[11] Because of this unique combination of features, this form of diabetes is sometimes referred to as Type 1.5 diabetes.

There is a wide difference in prevalence of LADA among various population groups across the globe. Recently, Arikan et al.,[12] in a study among Turkish population, comparing long-term complications of diabetes among GAD-Ab+ and GAD-Ab− patients, documented a prevalence of 31% of LADA while Bosi et al.,[13] in a population-based study in Italy, found as low as 2.8% prevalence of LADA. In a similar previous study in Southern Nigeria, Ipadeola et al.[14] and Adeleye et al.[15] reported a prevalence of LADA among T2DM patients to be 11.9% and 14.0%, respectively.

In Ghana, Agyei-Frempong et al.[16] in a clinic-based study reported a prevalence of 11.7% and also found less metabolic syndrome indices among the GAD-Ab+ than in GAD-Ab− patients. Among Caucasians, Tuomi et al.[5] reported a prevalence of LADA among Finnish population to be 9.2% while Hwangbo et al.[17] in Korea found 4.3%. In both studies, they found decreased secretory capacity of the β-cells, less BMI and hypertension, decreased triglycerides (TGs), and poor glycemic control in the LADA group. The differences in the prevalence of LADA among populations may not be unrelated to the characteristics of the study populations, genetic predisposition, type of assay used, and the adopted criteria for diagnosis.

It is evident from most of the previous studies, from different populations, race and regions of the globe, that LADA patients exhibit rapid deterioration of β-cell function as manifested in the poor glycemic control and subsequent insulin dependency. This needs to be identified early and proper classification of diabetic subjects so as to reduce and or delay the consequences of long-term complications of diabetes among LADA group of patients.

In this study, we measured GAD-Ab among noninsulin-requiring T2DM patients with the aim to estimate the prevalence of LADA in Northern Nigeria and also to compare the clinical characteristics between GAD-Ab+ and that of GAD-Ab− subgroups of diabetics.

Methods

The study was a descriptive and cross-sectional; it involved a study population drawn from T2DM patients attending the diabetes clinic of a tertiary health institution in Northern Nigeria. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution and lasted 1 year between December 2007 and January 2008.

Subjects

Two-hundred consecutive T2DM patients, who consented, were recruited from the diabetes clinic based on some selection criteria.

Inclusion criteria include noninsulin-requiring T2DM patient of at least 6 months duration and age of 30 or more years. Patients on insulin, pregnant women, presence of systemic diseases or organ failure, and use of drugs, especially steroids, were excluded from the study.

Clinical procedure

The consecutive patients attending the diabetes clinic who satisfied the inclusion criteria were administered questionnaires on the first contact. The demographic data including age, sex, age at onset, duration of diabetes, history of hypertension or diabetes, and family history of diabetes were recorded.

All subjects had clinical examination. The weight was measured to the nearest 0.5 kg and height in meters using stadiometer. BMI was calculated from weight and height.[18] Waist circumference (WC) was measured to the nearest centimeter at the midpoint between the lowermost rib and the anterior superior iliac spine while hip circumference was measured at the level of greater trochanter. The patients were then asked to come for a next visit (2 weeks) after fasting for 8–12 h.

Sample collection

On the second visit, 10 ml of fasting venous blood was taken from all the subjects. The samples were immediately separated, and the plasma stored at −22°C. All the patients had their plasma samples analyzed for glucose, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), TG, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-peptide, and anti-GAD-Ab.

Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody

The GAD-Ab estimation was done using Kronus Kronus anti glutamic acid decarboxylase kit (ELISA), Boise, USA. It depends on the ability of GAD autoantibodies to act divalently and forms a bridge between GAD coated on ELISA plate wells and liquid phase GAD biotin. The GAD-biotin bound is then quantitated by addition of streptavidin-peroxidase and a chlorogenic substrate tetramethylbenzidine with reading of final absorbance at wavelengths (450 and 405 nm) to obtain maximum measuring range (4–200 units/ml of WHO reference preparation). Less than 5 units/ml is considered positive.[19]

Fasting plasma glucose

Plasma glucose was estimated using glucose oxidase method.

Glycated hemoglobin

The principle involved is micro-column method as a direct way of estimating HbA1c. After preparing the hemolysate where the labile fraction is eliminated, HbA1c is specifically eluted after washing away; the HbA1a+ b fraction is quantified by direct photometric reading at 415 nm. HbA1c Quantitative kit (Agappe Diagnostic Ltd., India) was used.[20]

Lipids

TC was estimated through an enzymatic method using the generated color to show the amount of cholesterol in the sample. HDL-C was estimated after the precipitation of LDL-C and very LDL-C by polyanions in the presence of magnesium ion. TGs in the sample were measured by the same spectrophotometry while LDL-C was estimated using fried Wald's formula: LDL-C = TC – HDL-C+ TGs/2.2.

C-Peptide

C-peptide estimation was done using Kronus ELISA kit (Boise, USA); reading was done at 450 nm with value <1.0 µ/ml as considered low.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical package for social sciences version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and it was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student's t-test was used to compare means while Chi-square was used to compare categorical/nominal groups. A binary logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between dependent and independent variables. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The study population comprised 200 noninsulin-requiring Type 2 diabetic subjects who were attending the diabetic clinic in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria. The mean (SD) age of the subjects was 53 (9.2) years, range (34–75), and comprising 80 (40%) males and 120 (60%) females [Table 1].

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the study population

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 53 (9.21) |

| AAD | 46 (9.37) |

| DOD | 7 (5.46) |

| BMI | 26.8 (5.21) |

| WC | 91.9 (11.7) |

| WHR | 0.99 (0.05) |

| SBP | 142 (23.8) |

| DBP | 89 (11.1) |

| FBG | 8.2 (3.21) |

| PPG | 12.2 (3.53) |

| HbA1c | 7.45 (1.85) |

| TC | 5.0 (0.94) |

| LDL-C | 3.8 (0.96) |

| TG | 1.1 (0.34) |

| HDL-C | 0.72 (0.23) |

AAD=Age at diagnosis, DOD=Duration of diabetes, BMI=Body mass index, WC=Waist circumference, WHR=Waist hip ratio, SBP=Systolic blood pressure, DBP=Diastolic blood pressure, FBG=Fasting blood glucose, PPG=Postprandial glucose, HbA1c=Glycated hemoglobin, TC=Total cholesterol, LDL-C=Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C=High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=Triglyceride, SD=Standard deviation

Prevalence of glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody

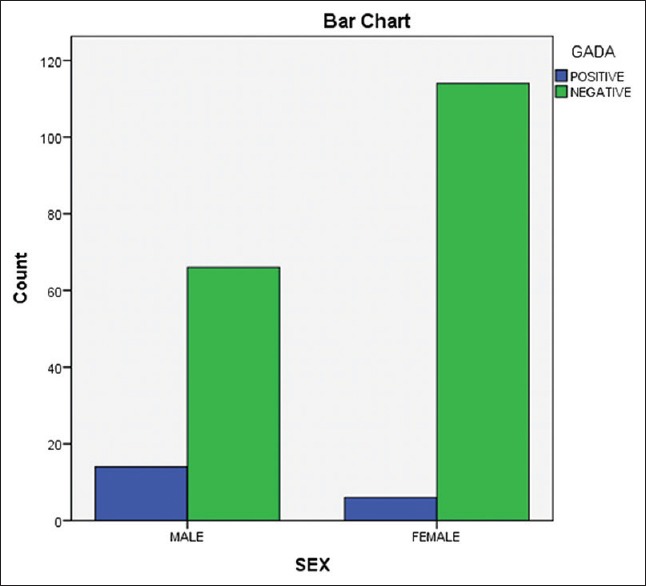

Of the 200 patients studied, 21 (10.5%) were found positive for GAD-Ab comprising 15 (71%) males and 6 (29%) females. Chi-square = 4.2, P < 0.05 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The distribution of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody by sex

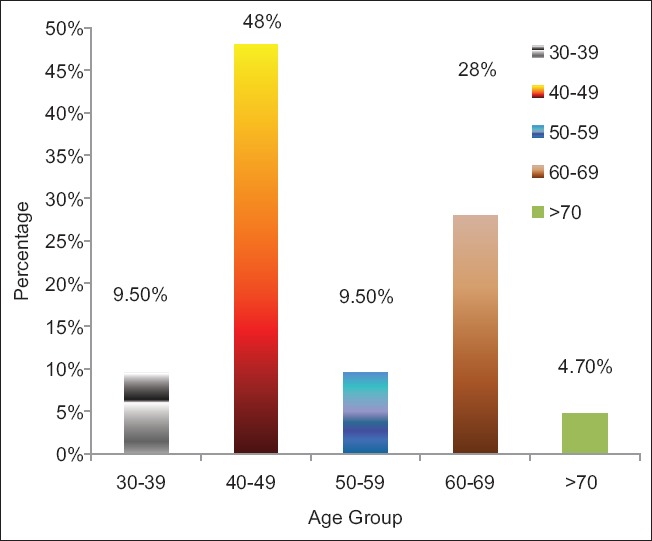

Figure 2 shows that 48% of GAD-Ab was found in the age group of 40–49, 28% in 60–69, 10% each was found in the group 30–39 and 50–59 while above 70 years has 4.7%.

Figure 2.

The distribution of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody positive by age group

Clinical characteristics of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies positive and negative diabetic patients compared

The mean age (SD) of patients with GAD-Ab+ (n = 21) and GAD-Ab− (n = 179) was 52 (11) and 53 (9), P > 0.05, respectively. There was also no significant difference at the age of onset and duration of diabetes among the two groups. Both the two groups of the diabetic patients were noninsulin- requiring and also were not place on any of the anti-lipid drugs.

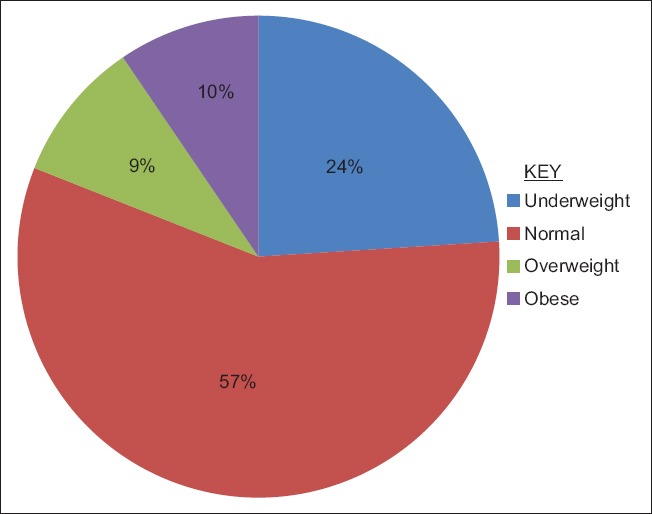

The mean BMI of GAD-Ab+, 22.1 (12.4), was significantly lower than that of GAD-Ab−, 27.3 (4.9), P = 0.002 [Table 2]. The majority of the GAD-Ab+ subjects have either normal BMI (57%) or underweight (24%) [Figure 3]. The mean WC of GAD-Ab+ subjects was significantly lower than that of GAD-Ab− subjects, 80.1 (12.4) and 93.2 (10.9), respectively, P = 0.001. There was no difference in waist-hip ratio between the two groups. Both the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were lower in GAD-Ab+ subjects although of no statistical significance.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies positive and negative

| Variable | Mean (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAD positive | GAD-negative | ||

| Age | 52.0 (11.02) | 53.0 (9.06) | 0.937 |

| AAD | 46.7 (10.23) | 45.9 (9.32) | 0.810 |

| DOD | 6.1 (3.75) | 7.1 (5.63) | 0.582 |

| BMI | 22.1 (5.09) | 27.3 (4.98) | 0.002* |

| WC | 80.1 (12.38) | 93.2 (10.92) | 0.001* |

| WHR | 0.99 (0.29) | 1.00 (0.05) | 0.865 |

| SBP | 139.6 (15.96) | 142.5 (24.6) | 0.712 |

| DBP | 86.0 (8.430) | 89.5 (11.3) | 0.347 |

| FBG | 8.7 (2.19) | 8.1 (3.31) | 0.602 |

| PPG | 12.7 (3.11) | 12.1 (3.58) | 0.633 |

| TC | 5.0 (0.78) | 5.0 (0.96) | 0.993 |

| LDL-C | 3.97 (0.79) | 3.8 (0.98) | 0.650 |

| HDL-C | 0.69 (0.17) | 0.72 (0.24) | 0.669 |

| TG | 0.87 (0.42) | 1.07 (0.33) | 0.069 |

| HbA1c | 8.3 (1.4) | 7.0 (2.1) | 0.003* |

| C-peptide | 0.84 (0.05) | 1.72 (0.43) | 0.002* |

AAD=Age at diagnosis, DOD=Duration of diabetes, BMI=Body mass index, WC=Waist circumference, WHR=Waist hip ratio, SBP=Systolic blood pressure, DBP=Diastolic blood pressure, FBG=Fasting blood glucose, PPG=Postprandial glucose, HbA1c=Glycated hemoglobin, TC=Total cholesterol, LDL-C=Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C=High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=Triglyceride, GAD=Glutamic acid decarboxylase, SD=Standard deviation

Figure 3.

Percentage of body mass index classes among glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody positive subjects

The glucose control among the two groups was poorer in GAD-Ab+ subject than in the GAD-Ab− with mean HbA1c of 8.3 (1.4) and 7.0 (2.1), respectively, P = 0.003. There was no significant difference in mean fasting blood glucose and 2-hrpp between the two groups.

The mean TG is lower in GAD-Ab+, 0.87 (0.42), than in GAD-Ab−, 1.07 (0.33), P > 0.05. There were no differences in the mean values of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C between the two groups.

The mean C-peptide level in GAD-Ab+ is significantly lower than in GAD-Ab− patients, 0.84 (0.05)/1.72 (0.43), P < 0.05.

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to ascertain the effects of age, sex, BMI, WC, HbA1c, and TG to predict GAD-Ab+ among the patients. In this study, it was found that the WC and male sex were predictors of GAD-Ab+ among T2DM subjects. The logistic regression model was 48 Nagelkerke R2, and 96% predicted correctly that GAD-Ab occurs from the independent variables contribution of sex and WC, P < 0.05.

Discussion

The 200 noninsulin-requiring Type 2 diabetic patients who were studied have age range of 34–75 years and have more females than males (120 vs. 80 or a ratio of 3:2). This pattern of diabetes distribution between gender groups is in keeping with earlier work as reported by Bakari and Onyemelukwe[21] and more recently by Olamoyegun et al.[22] both in Nigeria.

LADA is a form of autoimmune diabetes that occur late, or with advancing age, and noninsulin- requiring at onset.[9] It is characterized by progressive and slowly β-cell destruction by an autoimmune mechanism involving attack by GAD, ICA, or IA-2 autoantibodies. The GAD-Ab is said to be more sensitive than IA-2 and higher titer in adults than in children.[4,5] This explained the reason of using GAD-Ab, as against other autoantibodies, to detect LADA subgroup of diabetes among T2DM subjects.

The prevalence of LADA among T2DM subjects in this study was found to be 10.5% (21/2000). In a previous study of GAD-Ab among T2DM patients in Southwest Nigeria, a prevalence rate of 11.9% was documented.[14] Adeleye et al.[15] in a similar survey also, in Southwest Nigeria, reported a prevalence rate of 14.0%. The observed prevalence rates between these previous studies and the present one may be explained by the differences in the age group of those found with GAD-Ab+ and the selection of noninsulin-requiring subjects at the outset of this study.

In similar studies in Ghana, West Africa, Agyei-Frempong et al.[16] found a rate of 11.7% while in Kenya, East Africa, a lower rate of 5.7% was documented by Otieno et al.[23] Elsewhere in Korea, Hwangbo et al.[17] reported a prevalence rate of 4.3% while Brahmkshatriya et al.[9] from India found a rate of 5.0%. The prevalence of GAD-Ab among T2DM across populations is greatly varied which ranges from as low as 2.8% to more than 31%. The observed differences in prevalence may be related to sampling technique, patient demography, genetic predisposition, and type of assay used. Table 3 depicts the prevalence rates of GAD-Ab+ among different populations.

Table 3.

Prevalence of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody positive (late autoimmune diabetes in adult) in type two diabetes subjects among different population groups

| Author | Country | Study type | Subjects (n) | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | Northern Nigeria | Clinic-based | 200 | 10.5 |

| Adeleye et al.[15] | Southwest Nigeria | Clinic-based | 160 | 11.9 |

| Ipadeola et al.[14] | Southwest Nigeria | ✓ | 235 | 14.0 |

| Agyei et al.[16] | Ghana | ✓ | 120 | 11.7 |

| Otieno et al.[23] | Kenya | ✓ | 124 | 5.7 |

| Hwangbo et al.[17] | Korea | ✓ | 462 | 4.3 |

| Tuomi et al.[5] | Finland | Population-based | 1122 | 9.3 |

| Bosil et al.[13] | Italy | ✓ | 2076 | 2.8 |

| Zinman et al.[31] | North America and Europe | ✓ | 4134 | 4.2 |

| Arikan et al.[12] | Turkey | Clinic-based | 54 | 31 |

| Brahmkshatriya et al.[9] | India | ✓ | 500 | 5.0 |

In this study, males were found to have GAD-Ab+ more than their female counterparts; 71% (15/21):29% (6/21), χ2 = 4.2, P < 0.05 [Figure 1]. A similar finding was reported by Brahmkshatriya et al.[9] among Indian population; however, previous studies in Southwest Nigeria reported no gender bias of GAD-Ab+ among T2DM patients.[14,15] The observed differences of GAD-Ab among gender between the current study (Northern Nigeria) and the previous (Southern Nigeria) may be due to population demographics and/or genetic predisposition.[24]

The most common age group found to have GAD-Ab+, in this study, was 40–49 years 48% [Figure 2]. This finding supported previous studies that showed advancing age, just like T2DM, is a risk factor for the development of LADA.[5,15,25] This further buttress the fact that the pathogenesis of LADA has both the autoimmune and insulin resistance components, advancing age is also known to be a risk factor for insulin resistance, which has been shown to play a role in LADA.[26]

In this study, we found the mean BMI and WC of patients with GAD-Ab+ to be significantly lower than that of the patients with GAD-Ab− (22.1 ± 5.0, 80.1 ± 12.4 vs. 27.3 ± 4.9, 93.2 ± 10.9), P < 0.05. In a similar study in Southern Nigeria, Ipadeola et al.[14] reported that LADA patients were leaner and had poor glycemic control than T2DM patients. Agyei-Frempong et al.[16] in a study of autoimmune diabetes among Ghanaians documented lower central obesity among LADA than in T2DM subjects. These findings supported the fact that LADA patient shared similar characteristics with T1DM of been lean, less metabolic indices, and insulin dependency.

Other indices of metabolic syndrome including hypertension, HDL-C, and TG tended to be lower in GAD-Ab+ subjects though of no significance value. Similar studies among Europeans showed significantly lower metabolic syndrome parameters among LADA patients.[8,27,28] Arikan et al.[12] in a study of microvascular complications among LADA patients in Turkey found lower BMI, C-peptide, and lesser age at onset of diabetes in this subset of patients.

In China national survey on GAD-Ab+ among T2DM, Zhou et al.[7] documented that LADA patients were significantly leaner and had decreased C-peptide level and less metabolic syndrome than GAD-Ab− T2DM patients. The study further showed that patients with high GAD-Ab+ are phenotypically different from those with low GAD-Ab+. This showed that GAD-Ab+ could be used for LADA stratification and accurate therapeutic choice.

It was also reported among Caucasians that GAD-Ab+ level correlates well with the β-cell function as exhibited by the level of C-peptide.[8,29,30,31] In this study, we found poorer glycemic control among GAD-Ab+ than in GAD-Ab− subjects as demonstrated in the level of HbA1c. We also observed lower C-peptide level in GAD-Ab+ than in those with GAD-Ab− patients which suggest decreased secretory capacity of the β-cells following the autoimmune process in GAD-Ab+ patients.

Insulin resistance as the major T2DM pathologic mechanism was also found to play a role in GAD-Ab+ or LADA patients.[10] Hence, it is rational to expect that LADA subgroup shares the same characteristics with both T1DM and T2DM, and therapeutic approaches must take this into cognizance.

Conclusion

We concluded that the prevalence of LADA among recently diagnosed noninsulin-requiring T2DM patients in Northern Nigeria was 10.5%. The patients were lean, more common in males and age group 40–49 years, exhibited less metabolic syndrome, and decreased β-cell secretory capacity as demonstrated by low C-peptide level.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications, Part 1: Report of the WHO Consultation Geneva. 1999 (Tech. Report. Ser No. WHO/NCD/NCS/992) 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):562–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks-Worrell BM, Boyko EJ, Palmer JP. Islet autoimmunity in T2DM is associated with a significantly more rapid β-cell functional decline. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3286–93. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naik RG, Palmer JP. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2003;4:233–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1025148211587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuomi T, Carlsson A, Li H, Isomaa B, Miettinen A, Nilsson A, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of type 2 diabetes with and without GAD antibodies. Diabetes. 1999;48:150–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mollo A, Hernandez M, Marsal JR, Esquerda A, Rius F. β-cell function is related to GAD antibody positive in patients with LADA. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;24:446–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Z, Xiang Y, Ji L, Jia W, Ning G, Huang G, et al. Frequency, immunogenetics, and clinical characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes in China (LADA China study): A nationwide, multicenter, clinic-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes. 2013;62:543–50. doi: 10.2337/db12-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies H, Brophy S, Fielding A, Bingley P, Chandler M, Hilldrup I, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) in South Wales: Incidence and characterization. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1354–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brahmkshatriya PP, Mehta AA, Saboo BD, Goyal RK. Characteristics and prevalence of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) ISRN Pharmacol 2012. 2012:580202. doi: 10.5402/2012/580202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schernthaner G, Hink S, Kopp HP, Muzyka B, Streit G, Kroiss A. Progress in the characterization of slowly progressive autoimmune dibetes in adult patients (LADA or type 1,5 diabetes) Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109(Suppl 2):S94–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18573. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castleden HA, Shields B, Bingley JP, Williams AJ, Sampson M, Walker M, et al. GAD antibodies in probands and their relatives in a cohort clinically selected for type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:834–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arikan E, Sabuncu T, Ozer EM, Hatemi H. The clinical characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults and its relation with chronic complications in metabolically poor controlled Turkish patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2005;19:254–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosi EP, Garancini MP, Poggiali F, Bonifacio E, Gallus G. Low prevalence of islet autoimmunity in adult diabetes and low predictive value of islet autoantibodies in the general adult population of Northern Italy. Diabetologia. 1999;42:840–4. doi: 10.1007/s001250051235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ipadeola A, Adeleye JO, Akinlade KS. Latent autoimmune diabetes amongst adults with type 2 diabetes in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Prim Care Diabetes. 2015;9:231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adeleye OO, Ogbera AO, Fasanmade O, Ogunleye OO, Dada AO, Ale AO, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults (LADA) and it's characteristics in a subset of Nigerians initially managed for type 2 diabetes. Int Arch Med. 2012;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agyei-Frempong MT, Titty FV, Owiredu WK, Eghan BA. The prevalence of autoimmune diabetes among diabetes mellitus patients in Kumasi, Ghana. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11:2320–5. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.2320.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwangbo Y, Kim JT, Kim EK, Khang AR, Oh TJ, Jang HC, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients with positive anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody. Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36:136–43. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults – The evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baekkeskov S, Aanstoot HJ, Christgau S, Reetz A, Solimena M, Cascalho M, et al. Identification of the 64K autoantigen in insulin-dependent diabetes as the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase. Nature. 1990;347:151–6. doi: 10.1038/347151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisse E, Abragam EC. New less temperature sensitive microchromatographic method for the separation and quantification of glycosylated hemoglobin using a non-cyanide buffer system. J Chromatogr. 2002;52:147–55. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakari AG, Onyemelukwe GC. Indices of obesity among T2DM Hausa – Fulani Nigerians. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2005;13:28–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olamoyegun AM, Oluyombo R, Iwuala OS, Gbadegesin AB, Olaifa O, Babatunde AO, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for diabetes in semi-urban communities in South West, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2014;33:264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otieno CF, Huho AN, Omonge EO, Amayo AA, Njagi E. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical and aetiologic types, therapy and quality of glycaemic control of ambulatory patients. East Afr Med J. 2008;85:24–9. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v85i1.9602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guglielmi C, Palermo A, Pozzilli P. Latent autoimmune diabetes in the adults (LADA) in Asia: From pathogenesis and epidemiology to therapy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 2):40–6. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlsson S, Midthjell K, Tesfamarian MY, Grill V. Age, overweight and physical inactivity increase the risk of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: Results from the Nord-Trøndelag health study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:55–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pipi E, Marketou M, Tsirogianni A. Distinct clinical and laboratory characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults in relation to type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:505–10. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawa MI, Thivolet C, Mauricio D, Alemanno I, Cipponeri E, Collier D, et al. Metabolic syndrome and autoimmune diabetes: Action LADA 3. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:160–4. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Römkens TE, Kusters GC, Netea MG, Netten PM. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of insulin-treated, anti-GAD-positive, type 2 diabetic subjects in an outpatient clinical department of a Dutch teaching hospital. Neth J Med. 2006;64:114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roh MO, Jung CH, Kim BY, Mok JO, Kim CH. The prevalence and characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) and its relation with chronic complications in a clinical department of a university hospital in Korea. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50:129–34. doi: 10.1007/s00592-010-0228-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Zhou ZG, Huang G, Ouyang LL, Li X, Yan X. Six-year follow-up of pancreatic beta cell function in adults with latent autoimmune diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2900–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinman B, Kahn SE, Haffner SM, O’Neill MC, Heise MA, Freed MI ADOPT Study Group. Phenotypic characteristics of GAD antibody-positive recently diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes in North America and Europe. Diabetes. 2004;53:3193–200. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]