Abstract

A variety of xenobiotic chemicals, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), aryl- and heterocyclic amines and tobacco related nitrosamines, are ubiquitous environmental carcinogens and are required to be activated to chemically reactive metabolites by xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes, including cytochrome P450 (P450 or CYP), in order to initiate cell transformation. Of various human P450 enzymes determined to date, CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A13, 2A6, 2E1, and 3A4 are reported to play critical roles in the bioactivation of these carcinogenic chemicals. In vivo studies have shown that disruption of Cyp1b1 and Cyp2a5 genes in mice resulted in suppression of tumor formation caused by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, respectively. In addition, specific inhibitors for CYP1 and 2A enzymes are able to suppress tumor formation caused by several carcinogens in experimental animals in vivo, when these inhibitors are applied before or just after the administration of carcinogens. In this review, we describe recent progress, including our own studies done during past decade, on the nature of inhibitors of human CYP1 and CYP2A enzymes that have been shown to activate carcinogenic PAHs and tobacco-related nitrosamines, respectively, in humans. The inhibitors considered here include a variety of carcinogenic and/or non-carcinogenic PAHs and acethylenic PAHs, many flavonoid derivatives, derivatives of naphthalene, phenanthrene, biphenyl, and pyrene and chemopreventive organoselenium compounds, such as benzyl selenocyanate and benzyl selenocyanate; o-XSC, 1,2-, 1,3-, and 1,4-phenylenebis( methylene)selenocyanate.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450, Metabolic activation, Chemical carcinogenesis, Enzyme inhibition, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Tobacco-related nitrosamines

INTRODUCTION

Rendic and Guengerich have recently summarized the roles of human xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in the activation of a variety of environmental carcinogens and mutagens to chemically reactive metabolites by searching more than 500 literatures reported until 2012 (1). Cytochrome P450 (P450 or CYP), sulfotransferase, aldo-keto reductase, N-acetyltransferase, cyclooxygenase, and flavon-containing monooxygenase are important enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of many carcinogens and their contributions to the activation of procarcinogens and promutagens have been estimated to be about 66%, 13%, 8%, 7%, 2%, and 1%, respectively (1). P450 enzymes have been shown to play major roles in activating these carcinogens, based on the analysis of formation of chemically reactive metabolites, DNA adduct and damage, chromosomal abbreviation, and bacterial mutagenicity and genotoxicity assays such as Ames and umu test systems (2–8). Our previous studies using umu genotoxicity assay with human P450 enzymes in conjunction with the results obtained from Ames mutagenicity assay and other detection systems reported so far (6,7–19) have suggested that human CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, 2A13, 2E1, and 3A4 are major enzymes involved in the activation of various environmental carcinogens including PAHs and tobacco-related nitrosamines (Table 1). In this review, we first describe in vivo studies on the roles of CYP1 and 2A enzymes in the formation of tumors caused by various chemical carcinogens; these are reported using gene-knockout mice and specific P450 inhibitors. Then, we summarize recent progress, mainly our in vitro studies done during the past decade, on the nature of chemical inhibitors of human P450 enzymes that participate in carcinogen activation (20–31).

Table 1.

Major human P450 enzymes involved in the bioactivation of chemical carcinogens

| P450 | Group of carcinogen | Carcinogens activated by P450s |

|---|---|---|

| CYP1A1 CYP1A2 CYP1B1 |

PAH | Benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (7,12-DMBA), benz[a]anthracene (B[a]A), benzo[c]phenenthrene, 5-methylchrysene, dibenzo[a,l]pyrene (DB[a,l]P, 3-methylcholanthrene (3-MC), fluoranthene, and other PAHs, and their dihydrodiol derivatives |

| Arylamine | 2-Acetylaminofluorene, 2-aminofluorene, 2-aminoanthracene, 6-aminochrysene | |

| Heterocyclic amine | 2-Amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ), 2-amino-3,5-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (MeIQ), 2-amino-6-methyldipyrido[1,2-a: 3′,2′-d]imidazole (Glu-P-1), 3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole (Trp-P-1), 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), and others | |

| Nitroarene | 1-Nitropyrene, 2-nitropyrene, 6-nitrochrysene | |

| Estrogen | 17β-estradiol, estrone | |

| CYP2A6 CYP2A13 |

Nitrosamine | 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), N-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) |

| Mycotoxin | Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) | |

| Arylamine | 2-Aminofluorene, 2-aminoanthracene | |

| CYP2E1 | Nitrosamine | Dimethylnitrosamine, diethylnitrosamine, NNK, NNN |

| Arylhydrocarbon | Styrene | |

| CYP3A4 | Mycotoxin | Aflatoxin B1, aflatoxinG1, sterigmatocystin, dihydrodiol derivatives of PAHs |

In vivo studies of suppression of tumor formation caused by procarcinogens in gene knockout mice

Buters et al. (32) have first reported that disruption of Cyp1b1 gene in mice causes suppression of formation of malignant lymphomas and other tumors induced by 7,12-DMBA as well as decreases in metabolizing 7,12-DMBA to a proximate carcinogenic 3,4-diol metabolite in primary embryoni stem cells (isolated from Cyp1b1 null mice) that had been treated with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (Table 2). These cell lines express Cyp1a1 protein at significant levels, but not Cyp1b1 protein, indicating that Cyp1b1 has a major role in activating 7,12-DMBA in vivo (32). The Cyp1b1-null mice have also been reported to be reduced in formation of ovarian cancers at a low dose of 7,12-DMBA (33), ovarian and skin tumors caused by DB[a,l]P (34,35), and skin tumors by dibenzo[def,p]chrysene (DB[a,l]P) (36). Disruption of Cyp1b1-null mice has been shown to be reduced in pre-B cell apoptosis (37), bone marrow cytotoxicity (38), and spleen cell immunotoxicity (39) by treatment with 7,12-DMBA. Epoxide hydrolase and arylhydrocarbon hydroxylase have also been shown to play important roles in the formation of skin tumor caused by 7,12-DMBA and B[a]P, respectively, in gene knockout mice (40,41).

Table 2.

Suppression of tumor formation caused by chemical carcinogens in gene knockout mice in vivo

| Disruption of gene | Carcinogen administered | Suppression of tumor formation in organs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyp1b1 | 7,12-DMBA | Lymphoid tissue | Buters et al. (32) |

| DB[a,l]P | Ovary, skin, lymphoid tissue | Buters et al. (34) | |

| 7,12-DMBA | Ovary | Buters et al. (33) | |

| 7,12-DMBA | Spleen (immunotoxicity) | Gao et al. (39) | |

| dibenzo[def,p]chrysene | Skin | Siddens et al. (36) | |

| Cyp2a5 | NNK | Lung | Megaraj et al. (47) |

| Cyp2abfgs | NNK | Lung | Li et al. (50) |

| Cyp2e1 | Dimethylnitrosamine | Liver | Kang et al. (52) |

| Epoxide hydrolase | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Miyata et al. (40) |

| Arylhydrocarbon receptor | B[a]P | Skin | Shimizu et al. (41) |

Thus, roles of CYP1B1 protein in the activation of various carcinogenic PAHs have been suggested in gene knockout mice in vivo. Of note, Luch et al. (42) have found that CYP1B1 plays a more important role than CYP1A1 in activating DB[a,l]P to highly reactive DB[a,l]P-11,12-diol-13,14-epoxides and our previous in vitro studies have shown that human CYP1B1 is more active in forming B[a]P-7,8-diol from B[a]P than CYP1A1 and 1A2 (43). Uno et al. have reported that CYP1A1 may be involved in detoxification and protection against oral B[a]P in mice, since CYP1A1 null mice died within 30 days after oral B[a]P (125 mg/kg), while wild-type mice did not show any signs of toxicity during the course of experiments (44). They also studied effects of oral B[a]P in Cyp1a1-, 1a2-, and 1b1-null mice and their double knockout mice and found that a balance of expression of Cyp1a1 and 1b1 proteins in several organs is important to understand the basis of toxicity and carcinogenicity caused by oral administration of B[a]P (45,46).

Megaraj et al. have shown that Cyp2A5-null mice are reduced in the formation of lung tumor caused by NNK and that CYP2A13 is suggested to play roles in bioactivating NNK to initiate lung tumor in a humanized mouse model (47). CYP2A13 genetic polymorphisms may cause individual differences in susceptibilities towards tobacco-related cancers in humans (47–49). In mice, other Cyp2-family enzymes as well as Cyp2a4 and 2a5 may be involved in NNK-induced tumor on analysis using Cyp2abfgs-null mice (49–51). Cyp2e1 has been reported to play key roles in the formation of liver tumors by dimethynitrosamine in the studies of gene knockout mice (52).

In vivo effects of P450 inhibitors on suppression of tumor formation caused by carcinogens in experimental animals

It has been reported that several PAH compounds suppress, prolong, or delay tumor formation caused by potent carcinogens such as 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P, dibenz[a,h]anthracene, and 3-MC in laboratory animals (Table 3) (53–58). Weak or non-carcinogen PAHs, such as B[e]P, have also been reported to reduce tumor fomation caused by environmental carcinogens (59–64), and as described below, B[e]P has been determined to be a potent inhibitor for CYP1 family enzymes (20). CYP1 inhibitors such as ANF, 9-hydroxyellipticine, and 1-ethynylpyrene have also been reported to have anticarcinogenic activities in mice treated with 7,12-DMBA and B[a]P (56,65,66). Furanocoumarin derivatives (such as imperatorin and bergamottin) and flavonoids (such as naringenin, apigenin, quercetin, and hesperidin), which have been reported to inhibit human CYP1, 2A, and/or 3A enzymes in vitro (23,24), have chemopreventive activities in experimental animals (67–73). 8-Methoxypsoralen and isothiocyanate derivatives, such as benzyl- and phenethyl isothiocyanates, which are the potent inhibitors of CYP2A6 and 2A13 (74,75), have chemopreventive activities in mice when these chemicals are administered before or just after the administration of NNK and azoxymethane (Table 3) (74–80).

Table 3.

Suppression by P450 inhibitors of tumor formation caused by chemical carcinogens in vivo by in laboratory animals (1)

| Inhibitor | Suggested P450 inhibition | Carcinogen administered | Suppression of tumor formation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a-Naphthoflavone | CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P | Skin | Gelboin and Kinoshita (53) |

| CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P | Skin | Kinoshita and Gelboin (54) | |

| CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Slaga et al. (56) | |

|

| ||||

| 9-Hydroxyellipticine | CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Lesca and Mansuy (65) |

|

| ||||

| Benzo[e]pyrene | CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | DiGiovanni et al. (60) |

| CYP1 | Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | Skin | DiGiovanni et al. (60) | |

|

| ||||

| 1,2,5,6-Dibenzofluorene | 3-MC | Skin | Riegel et al. (57) | |

| 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Hill et al. (58) | ||

|

| ||||

| 1-Ethynylpyrene | CYP1 | 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P | Skin | Alworth et al. (66) |

|

| ||||

| Imperatorin | CYP1, 2A, 3A | 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P | Skin | Cai et al. (67) |

| Bergamottin | CYP1, 2A 3A | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Kleiner et al. (68) |

| Isopimpinellin | CYP1, 2A 3A | 7,12-DMBA | Skin | Kleiner et al. (68) |

|

| ||||

| Naringenin | CYP1, 2A | 7,12-DMBA | Oral | Sulfikkarali et al. (70) |

|

| ||||

| Apigenin | CYP1, 2A | 7,12-DMBA | Oral | Silvan et al. (71) |

|

| ||||

| Quercetin | CYP1, 2A | NNK, B[a]P | Lung | Kassie et al. (72) |

|

| ||||

| Hesperidin | CYP2C, 3A | Azoxymethane | Colon | Tanaka et al. (73) |

|

| ||||

| 8-Methoxypsoralen | CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Takeuchi et al. (75) |

| CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Miyazaki et al. (76) | |

| CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Takeuchi et al. (77) | |

| CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Takeuchi et al. (74) | |

|

| ||||

| Benzyl isothiocyanate Phenyl isothiocyanate |

CYP1, 2A | B[a]P | Lung, stomach | Wattenberg et al. (78) |

| CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Morse et al. (79) | |

| CYP2A | NNK | Lung | Morse et al. (80) | |

|

| ||||

| BSC | CYP1, 2A 3A | Azoxymethane | Colon | Fiala et al. (82) |

| CYP1, 2A 3A | B[a]P | Stomach | El-Bayoumy (89) | |

|

| ||||

| p-XSC, BSC | CYP1, 2A 3A | 7,12-DMBA | Mammary | El-Bayaumy et al. (84) |

|

| ||||

| p-XSC | CYP1, 2A 3A | 7,12-DMBA | Lung | Prokopczyk et al. (85) |

| CYP1, 2A 3A | B[a]P, NNK | Lung | Prokopczyk et al. (86) | |

Synthetic organoselenium compounds such as BSC, and o-, m- and p-XSC, which are recently reported by us to inhibit human CYP1 and 2A enzymes (25,81), have chemopreventive activities in mice administered 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P, and NNK (Table 3) (82–89). El-Bayoumy et al. (87) reported that p-XSC is active in preventing tumor formation caused by NNK when it is injected before the administration of NNK, indicating that the mechanism of action of p-XSC is due to inhibition of P450s that activate NNK to active metabolites (47–51).

In vitro inhibition of carcinogen-activating P450 enzymes

Extensive studies have shown that there is a variety of xenobiotic and endogenous chemicals that inhibit individual forms of human P450s (6,20–26,90–92). Historically, many researchers have studied and searched specifc xenobiotic and endogenous inhibitors for P450 enzymes in order to examine roles of P450s in substrate oxidation reactions, to evaluate new drug development and drug-drug interaction in clinical trials, and to understand the basis of chemical toxicity and carcinogenesis (93–97). Following xenobiotic chemicals have been reported to be relatively specific inhibitors for individual human P450 enzymes; furafyllin, fluvoxamine, and a-naphthoflavone for CYP1 enzymes, methoxsalen, tranylcypromine, and tryptamine for CYP2A enzymes, ticlopine and thiotepa (triethylenethiophosphoramide) for CYP2B6, sulphaphenazole, fluconazole, and omeprazole for CYP2C enzymes, quinidine, terbinafine, and fluoxetine for CYP2D6, disulfiram, pyridine, and diethyldithiocarbamate for CYP2E1, and ketoconazole, itraconazole, and retionavir for CYP3A enzymes (6–8,20, 91,92,94).

Since CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, and 2A13 have been recognized to be key enzymes in understanding the basis of chemical carcinogenesis caused by a variety of carcinogenic PAHs and tobacco-related nitrosamines, we summarize, mainly our recent studies during the past decade, on the nature of numerous xenobiotic chemicals that inhibit these human P450 enzymes (20–31). Followings are described here that a) inhibition of CYP1 enzymes by a variety of PAHs and acetylenic PAH inhibitors, b) different mechanisms of inhibition of CYP1 enzymes by PAHs and acetylenic PAH inhibitors, c) inhibition of P450 enzymes by flavonoid derivatives, d) interaction of xenobiotic chemicals with CYP2A13 and 2A6, and e) inhibition of CYP1 and 2A enzymes by chemopreventive organoselenium compounds.

In vitro inhibition of CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 by xenobiotic chemicals

In humans, CYP1A1 and 1A2 share 80% amino acid seqence identity and are ~40% identical with CYP1B1 (98–101). cDNA clones and amino acid sequences of former two enzymes have been characterized in 1985–1986 (98–100), while a human CYP1B1 cDNA clone and amino acid sequence were reported in 1994 (101). The crystal structures of CYP1A2 (102), CYP1B1 (103), and CYP1A1 (104) all bound to ANF in the active site cavity of the enzymes have been reported and characterized.

A variety of chemical inhibitors for human CYP1A1 and 1A2 enzymes had been reported by many investigators (90,91,105–109). Since human CYP1B1 protein was not expressed in yeast and Escherichia coli and charactered until 1994–1997 (16,104,110,111), studies on the comparison of selectivities of xenobiotic inhibitors for CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 were examined in 1998 by us (112) and by other investigators (113–117). We first examined total of 24 polycyclic hydrocarbons, many containing acetylenic side chains for their abilities to inhibit 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation activities catalyzed by human CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 (112). We found that 1-(1-propynyl)pyrene and 2-(1-propynyl)phenanthrene nearly completely inhibited CYP1A1 at concentrations where no CYP1B1 inhibition was observed and that 2-ethynylpyrene and ANF nearly completely inhibited CYP1B1 at concentrations where no CYP1A1 inhibition was noted. All four of the above compounds also inhibited CYP1A2. We conclude that (i) several polycyclic hydrocarbons and their oxidation products are inhibitors of human CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1; (ii) of these inhibitors only some are mechanism-based inactivators; and (iii) some of the inhibitors are potentially useful for distinguishing between human CYP1A1 and 1B1 (112).

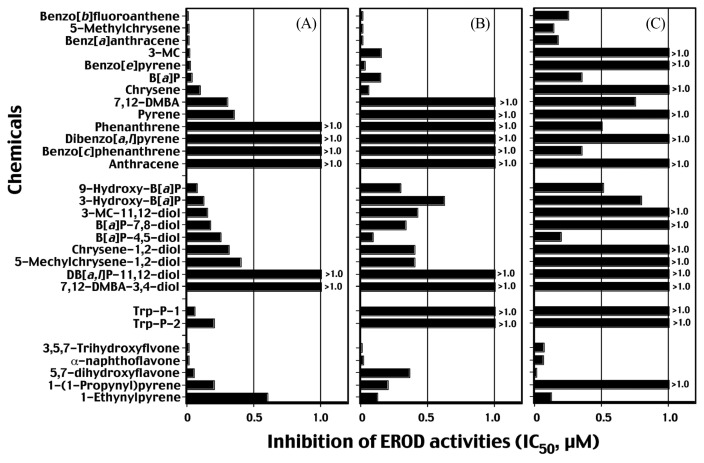

In 2006, we studied if carcinogenic or non- or weak carcinogenic PAHs as well as acetylenic PAHs, inhibit CYP1-catalytic activities (20), because some of these PAH compounds such as B[e]P and 1,2,5,6-dibenzofluorene prevented tumor formation caused by carcinogenic PAH compounds as described above (57–64). We examined following chemicals as benzo[b]fluoranthene, 5-methylchrysene, B[a]A, 3-MC, B[a]P, B[e]P, chrysene, 7,12-DMBA, pyrene, phenanthrene, DB[a,l]P, benzo[c]phenanthrene, anthracene, pyrene, and phenanthrene and several PAH metabolites, Trp-P-1, Trp-P-2, and flavonoids (Fig. 1). In the figure, inhibition of EROD activities are shown as IC50 values within 1.0 μM chemical concentration. Interestingly, B[a]A, benzo[b]fluoranthene, and 5-methylchrysene inhibited CYP1B1- and 1A2-dependent EROD activities with IC50 values of below 0.01 μM. The IC50 values obtained with CYP1A1-dependent EROD activities were always higher than those with CYP1A2 and 1B1. Our results also showed that B[e]P which have been reported to be weak or non-carcinogens (59–64), very strongly inhibited CYP1B1 and 1A2 but not CYP1A1 at 1 μM concentration. Conversely, potent carcinogens such as benzo[c]phenanthrene and DB[a,l]P did not show significant inhibition of EROD activities by P450s, except that the former PAH inhibited CYP1A1-dependent EROD activity with an IC50 of 0.33 μM. Metabolites of PAHs (e.g., 3-OH and 9-OH B[a]P and dihydrodiol derivatives of PAHs) were rather weak inhibitors of P450-dependent EROD activities as compared with the parent PAHs. As suggested by us and other investigators, 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone (galangin), 5,7-dihydroxyflavone (chrysin), and ANF were potent inhibitors for three CYP1 enzymes (20,105–108). Trp-P-1 and Trp-P-2 inhibited more strongly CYP1B1 than CYP1A1 and 1A2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition (IC50 values) of 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation (EROD) activities of CYP1B1 (A), 1A2, (B), and 1A1 (C) by PAHs, PAH metabolites, Trp-P-1 and Trp-P-2, and flavonoids and acetylenic PAHs. IC50 values exceeded over 1.0 μM are indicated in the figure. Data are taken from Shimada and Guengerich (20) with modification.

We also found that 5-methylchrysene, B[a]P, B[a]A, and DB[a,l]P inhibited metabolic activation of 5-methylchrysene-1,2-diol, (±)B[a]P-7,8-diol, and DB[a,l]P-11,12-diol to genotoxic metabolites catalyzed by CYP1B1 and 1A1 by measuring induction of umu gene expression in S. typhimurium NM2009 (20). The results suggest that these PAHs inhibit second step of metabolic activation of these dihydrodiols to DNA-damaging products as well as first step of metabolism (by measuring inhibition of EROD activitiy) (20). Thus, individual PAHs may affect their own and metabolism of other carcinogens catalyzed by CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1, and these phenomena may cause alteration in their ability to transform cells when single or complex PAH mixtures are ingested by mammals, influencing risk assessment (113–117).

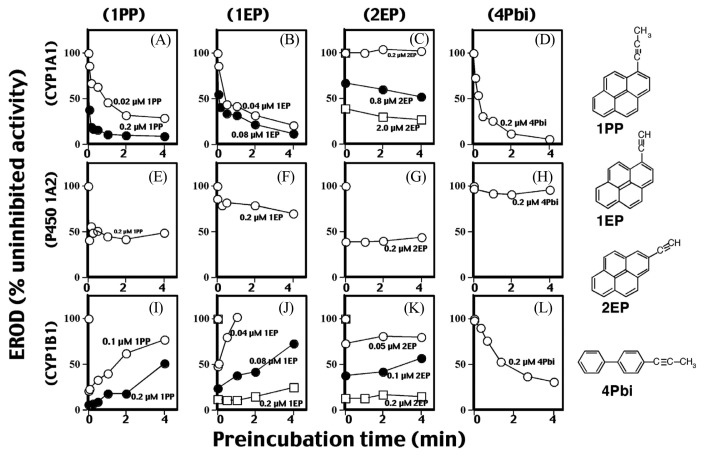

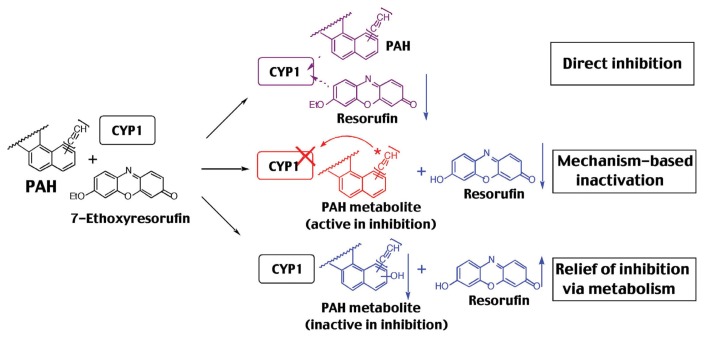

Different mechanisms of inhibition of P450 1A1-, 1A2-, and 1B1 by PAHs and acetylenic PAH inhibitors

Since reports have shown that many acetylenic PAH inhibitors inhibit P450-catalytic activities by mehanism-based manner (20,66,97,118–120), we have studied mechanisms of inhibition of CYP1-dependent EROD activities by PAHs used in this study (Fig. 2) (20–23). Our initial experiments show that preincubation of 1PP, 1EP, and 4Pbi with CYP1A1 for 0–4 min in the presence of NADPH caused inhibition of EROD activities in a time-dependent manner, indicating inhibition by a mechanism-based manner (Fig. 2A, 2B, 2D). However, 2EP inhibits P450 1A1 directly (preincubation does not affect the activities) (Fig. 2C) (21). CYP1B1-dependent EROD activity was inhibited by 1PP and 1EP without metabolism, and such decreases in activities were reversed with increasing pre-incubation time, indicating that CYP1B1 is able to metabolize 1PP and 1EP to products that loose inhibitory activity (relief of inhibition via metabolism) (Fig. 2I, 2J, 3). 4Pbi inhibited CYP1B1 in a mechanism-based manner similar to CYP1A1, although such inactivation in CYP1B1 (t1/2 = 3.4 min) was slower than that of the CYP1A1 (t1/2 = 15 s) (Fig. 2L, 2D). 2EP inhibited CYP1B1 directly. Four chemicals inhibited CYP1A2 directly (Fig. 2E–2H). These results indicated that there are three different mechanisms of inhibition of CYP1-enzymatic activities; a) direct inhibition, b) mehanism-based imnhibition (competitve inhibition), and c) relief of inhibition via metabolism as seen in 1PP and 1EP with CYP1B1 (Fig. 3). The mehanism namely, relief of inhibition via metabolism, was also observed in B[a]A, B[a]P, B[e]P, 5-methylchrysene, and 7,12-DMBA with CYP1B1, although chrysene and 3-MC inhibited CYP1B1 by competitive manner (21). Interestingly, these PAHs as B[a]A, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[j]fluoranthene, B[a]P, chrysene, 5-methylchrysene, B[e]P, dibenz[a,j]acridine, and 7,12-DMBA inhibited CYP1A2 by mechanism-based manner and inhibited CYP1A1 by a competiotive manner (20). Thus, these PAHs may modify the biological activities of their own and other PAH compounds through inhibition of CYP1-catalytic activities by different mechanisms (20.21).

Fig. 2.

Effects of preincubation time on inhibition of CYP1A1 (A–D), CYP1A2 (E–H), and CYP1B1 (I–L) dependent EROD activities by 1PP (A, E, and I), 1EP (B, F, and J), 2-EP (C, G, and K), and 4Pbi (D, H, and L). P450 (50 pmol) was pre-incubated with different concentrations of 1PP, 1EP, 2EP, and 4Pbi in the presence of 1mM NADPH during indicated periods of time, and then the reactions were started by the addition of 5 μM 7-ethoxyresorufin to determine EROD activities. The reactions were monitored at 25°C. Data are taken from Shimada et al. (21) with modification.

Fig. 3.

Three different mechanisms of inhibition of CYP1 enzymes by PAHs and acetylenic PAHs. Data are from Shimada et al. (21).

Inhibition of P450 enzymes by flavonoid derivatives

A variety of plant flavonoids are found in the environment and these natural products are shown to have various biological properties, e.g. anti-oxidative and anti-mutagenic activities, thus preventing cancer, heart disease, bone loss, and a number of diseases (121–123). These biological activities are reported to vary with the number and substitution positions of hydroxyl and/or methoxy groups in the flavonoid molecules (124–126). Inhibition of P450 enzymes by diverse flavonoid erivatives has been extensively studied in several laboratories (127–137).

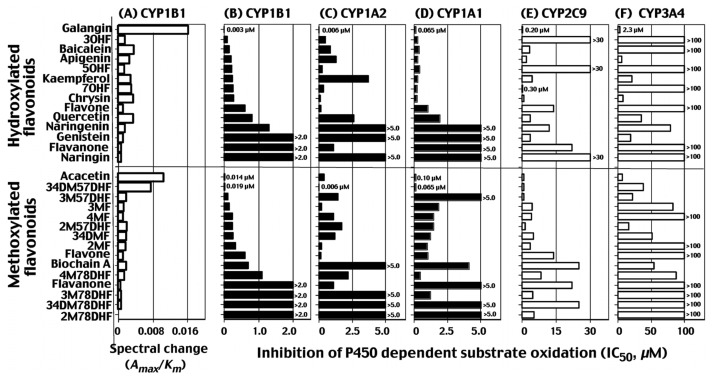

In 2009, we have reported that various chemicals including flavonoid, stilbene, pyrene, naphthalene, and biphenyl and their derivatives interact with CYP1B1 inducing reverse type I binding spectra and that these spectral changes are correlated with abilities to inhibit CYP1B1-dependent EROD activities (23). We further examined the relationship between spectral interaction of CYP1B1, 1A1, 1A2, 2C9, and 3A4 with total of 33 flavonoid derivatives and their potencies (IC50 values) to inhibit P450 catalytic activities by measuring EROD activities for CYP1B1, 1A1, and 1A2, flurbinoprofen 4′-hydroxylation activities for CYP2C9, and midazolam 4-hydroxylation activities for CYP3A4 (Fig. 4) (24). In the figure, results with selected 27 flavonoid derivatives are shown and the scale of IC50 values vary with 1~ 2.0 μM for CYP1B1, 0~5.0 μM for CYP1A2 and 1A1, 0~ 30 μM for CYP2C9, and 0~100 μM for CYP3A4 (Fig. 4). The potencies of spectral binding of CYP1B1 were found to correlate with the abilities to inhibit 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation activity catalyzed by CYP1B1 (r = 0.92). The presence of a hydroxyl group in flavone, e.g. 3-, 5-, and 7-monohydroxy- and 5,7-dihydroxyflavone (chrysin), decreased the 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of CYP1B1 from 0.6 μM (with flavone) to 0.09, 0.21, 0.25, and 0.27 μM, respectively, and 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone (galangin) was the most potent, with an IC50 of 0.003 μM. The introduction of a 4′-methoxy- or 3′,4′-dimethoxy group into 5,7-dihydroxyflavone yielded other active inhibitors of CYP1B1 with IC50 values of 0.014 and 0.019 μM, respectively. The above hydroxyl-and/or methoxy-groups in flavone molecules also increased the inhibition activity with CYP1A1 but not always towards CYP1A2, where 3-, 5-, or 7-hydroxyflavone, and 4′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone were less inhibitory than flavone itself, although CYP1A1 and 1A2 did not show spectral changes with these compounds. CYP2C9, which was also negative in inducing spectral changes with flavonoids, was more inhibited by 7-hydroxy-, 5,7-dihydroxy-, and 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavones than by flavone but was weakly inhibited by 3- and 5-hydroxyflavone. Flavone and several other flavonoids produced type I binding spectra with CYP3A4, but such binding was not always related to the inhibitiory activities towards CYP3A4 (24). The IC50 values with flavonoids to inhbit CYP2C9 and 3A4 were higher than those to inhibit CYP1B1, 1A2, and 1A1 (Fig. 4). These results indicate that there are different mechanisms of inhibition for CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2C9, and 3A4 by various flavonoid derivatives and that the number and position of hydroxyl and/or methoxy groups highly influence the inhibitory actions of flavonoids towards these enzymes.

Fig. 4.

Intensities of reverse type I binding spectra of CYP1B1 with 27 flavonoids (A) and inhibition by these flavonoids of EROD activities catalyzed by CYP1B1 (B), 1A1 (C), and 1A2 (D), flurbiprofen 4′-hydroxylation activities catalyzed by CYP2C9 (E), midazolam 4-hydroxylation activities catalyzed by CYP3A4 (F). The spectral changes are shown as spectral binding efficiency (ΔAmax/Km values). IC50 values are shown to be 0~1.0 μM for CYP1B1, 1A2, and 1A1, and 0~30 μM for CYP2C9 and 3A4. Abbreviations used; 3HF, 3-hydroxyflavone; 5HF, 5-hydroxyflavone; 7HF, 7-hydroxyflavone; 57DHF, 5,7-dihydroxyflavone; 357THF, 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone; 4′57THF, 4′5,7-trihydroxytrihydroxyflavone; 4′57THIF, 4′,5,7-trihydroxyisoflavone; 4′57THFva, 4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone; 4′57THFvaG, 4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone glycoside; 567THF, 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone; 34′57TetraHF, 3,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone; 33′4′57PHF, 3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone; 4′M57DHF, 4′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone; 4′M57DHisoF, 4′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyisoflavone; 2′MF, 2′-methoxyflavone; 3′MF, 3′-methoxyflavone; 4′MF, 4′-methoxyflavone; 3′4′DMF, 3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone; 2′M57DHF, 2′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone; 3′M57DHF, 3′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone; 3′4′M57DHF, 3′4′-dimethoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone; 2′M78DHF, 2′-methoxy-7,8-dihydroxyflavone; 3′M78DHF, 3′-methoxy-7,8-dihydroxyflavone; 4′M78DHF, 4′-methoxy-7,8-dihydroxyflavone; and 3′4′M78DHF, 3′,4′-dimethoxy-7,8-dihydroxyflavone. Data are taken from Shimada et al. (30) with modification.

Our molecular docking analysis supported that there are different orientations of interaction of various flavonoids with active sites of P450 enzymes examined, thus causing differences in inhibition potencies observed in these P450s (24).

Interaction of xenobiotic chemicals with human CYP2A13 and 2A6

CYP2A6 and 2A13 are expressed mainly in the liver and respiratory tract, respectively, in humans (4,138,139). CYP2A6 is active in catalyzing metabolism of several drugs, e.g. coumarin and phenacetin, and also metabolic activation of tobacco-related nitrosamines (including NNK and NNN) to carcinogenic metabolites (140,141). However, CYP2A13 is shown to be more active than CYP2A6 in activating NNK and NNN (140,141) and these findings are of interest because the latter enzyme is mainly expressed in respiratory organs, the sites of exposure to numerous environmental chemicals including NNK, NNN, and PAHs (4,138,139). As described above, several chemicals that inhibit CYP2A13 and 2A6 enzymes suppress tumor formation caused by NNK, 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P, and azoxymethane (Table 3) (47–51), it is interesting to examine whether various xenobiotic chemicals interact with and inhibit CYP2A13 and 2A6-dependent catalytic activities and are metabolized by these P450 enzymes (26,27).

A total of 68 chemicals including acenaphthene, acenaphtylenes, derivatives of naphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, pyrene, biphenyl, and flavone have been examined for their abilities to interact with human CYP2A13 and 2A6 (Fig. 5) (26). Fifty-one of these 68 chemicals induced stronger type I binding spectra (iron low- to high-spin state shift) with CYP2A13 than those seen with CYP2A6, i.e. the spectral binding intensities (ΔAmax/Ks ratio) determined with these chemicals were always higher for CYP2A13. In addition, benzo[c]phenanthrene, fluoranthene, 2,3-dihydroxy-2,3-dihydrofluoranthene, pyrene, 1-hydroxypyrene, 1-nitropyrene, 1-acetylpyrene, 2-acetylpyrene, 2,5,2′,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl, 7-hydroxyflavone, 5,7-dihydroxyflavone (chrysin), and 3,5,7,-dihydroxyflavone (galangin) were found to induce a type I spectral change only with CYP2A13. Coumarin 7-hydroxylation, catalyzed by CYP2A13, was strongly inhibited by acenaphthene, acenaphthylene, 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 2-naphththalene propargyl ether, 2-naphthalene ethyl propagyl ether. 3-ethynylphenanthrene, 1-acetylpyrene, flavone, flavanone, 7-hydroxyflavone, 2′-methoxyflavone, 5,7-dihydroxyflavone, and 2′-methoxy-5,7-dihydroxyflavone; these chemicals induced type I spectral changes with low Ks values (Fig. 5). Among various chemicals tested, benzo[c]phenanthrene, fluoranthene, pyrene, 1-hydroxypyrene, 1-nitropyrene, 1- and 2-acetylpyrene, 2,5,2′,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl, 7-hydroxyflavone, 5,7-dihydroxyflavone (chrysin), 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone (galangin), and ANF did not induce spectral changes with CYP2A6 (26). These chemicals were also found to be non-inhibitory or weak inhibitors of CYP2A6-dependent coumarin 7-hydroxylation activity. Thus, different selectivities of several chemicals in inducing spectral changes with these CYP2A enzymes were found, although it should be noted that 2-ethynylnaphthalene, naphthalene, 1-(1-propynyl)pyrene, 1-ethynylpyrene, 2-ethynylnaphthalene, phenanthrene, acenaphthene, acenaphthylene, biphenyl, and resveratrol had relatively similar tendencies to induce spectra with CYP2A13 and 2A6 (26).

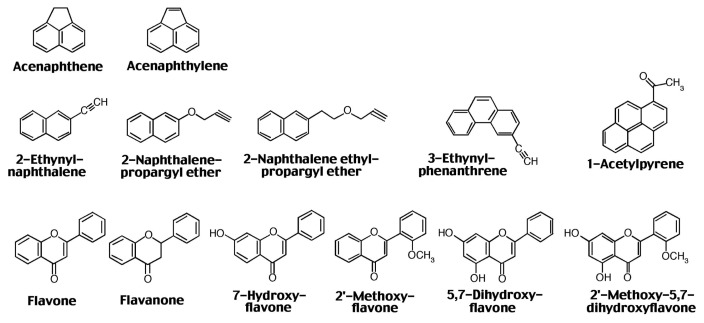

Fig. 5.

Compounds that show strong inhibition of CYP2A13-dependent coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities. Data are taken from Shimada et al. (26) with modification.

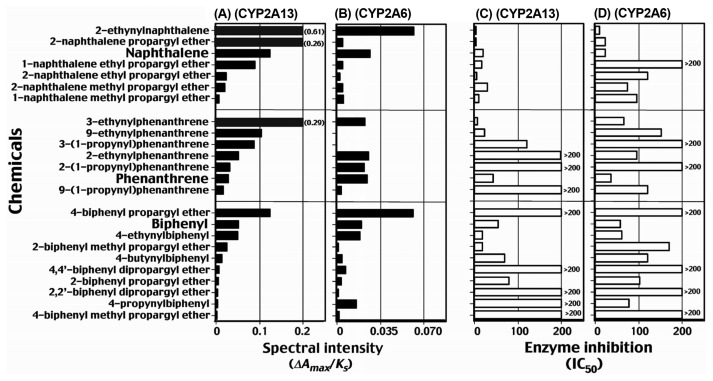

Twenty four chemicals including naphthalene, phenanthrene, biphenyl and their derivatives have been determined and compared to induce type I spectral changes (intensities, Amax/Ks ratio) with CYP2A13 (Fig. 6A) and 2A6 (Fig. 6B) and to inhibit coumarin 7-hydroxylation catalyzed by CYP2A13 (Fig. 6C) and 2A6 (Fig. 6D) (26,28–30). All of these chemicals induce type I binding spectra with CYP2A13 having high affinities with 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 2-naphthalene propargyl ether, naphthalene, 1-naphthalene ethylpropargyl ether, 2-naphthalene ethylpropargyl ether, 3-ethynylnaphthalene, 9-ethynylnaphthalene, 3-(1-propynyl)phenanthrene, 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 2-(1-propynyl) phenanthrene, phenanthrene, 4-biphenyl propargyl ether, biphenyl, and 4-ethynylbiphenyl (Fig. 6A). These spectral intensities in CYP2A13 tended to relate to the potencies of these chemicals to inhibit coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities catalyzed by this enzyme (Fig. 6C). All of these 24 chemicals also interacted with CYP2A6, however, spectral intensities and inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities found in CYP2A6 were lesser than those in CYP2A13, except that 4-propynylbiphenyl inhibited CYP2A6 (IC50 = 70 μM) more than CYP2A13 (IC50 > 200 μM); this compound was less active in inducing type I binding spectra with CYP2A13 (Fig. 6C, 6D).

Fig. 6.

Type I binding spectra of interaction of naphthalene, phenanthrene, biphenyl, and their derivatives with CYP2A13 (A) and 2A6 (B) and inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities of CYP2A13 (C) and 2A6 (D) by these chemicals. Data are taken from Shimada et al. (26,28–30) with modification.

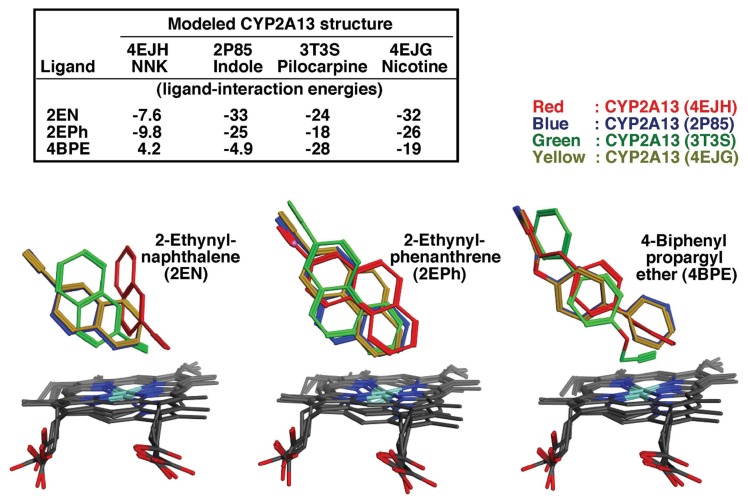

Since molecular docking analysis has been shown to be a useful tool for the studies of the interactions of various ligands with active sites of enzymes, such as P450s, we examined and compared the ligand-interaction energies (U values) with these 24 chemicals using reported crystal structures of CYP2A13 (4EJH), 2A13 (2P85), 2A13 (3T3S), and 2A13 (4EJG) (142–144) bound to NNK, indole, pilocarpine, and nicotine, respectively, and CYP2A6 (1Z10), 2A6 (3T3R), and 2A6 4EJJ) (145,146) bound to coumarin, pilocarpine, and nicotine, respectively (30). We first determined the U values of interaction of 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 2-ethynylphenanthrene, and 4-biphenylpropagyl ether with CYP2A13 (4EJH), CYP2A13 (2P85), CYP2A13 (3T3S), and CYP2A13 (4EJG) (Fig. 7) and obtained optimal U values on analysis with MMFF94x force field (30). The U values are somewhat different when different crystal structures of CYP2A13 were used (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Molecular docking analysis of ligand-interaction energies (U values) of 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 2-ethynylphenanthrene, and 4-biphenyl propargyl ether obtained using reported crystal structures of CYP2A13 (4EJH), 2A13 (2P85), 2A13 (3T3S), and 2A13 (4EJG) bound to NNK, indole, pilocarpine, and nicotine, respectively. Data are from Murayama, N., Shimada, T. and Yamazaki, H. (unpublished results).

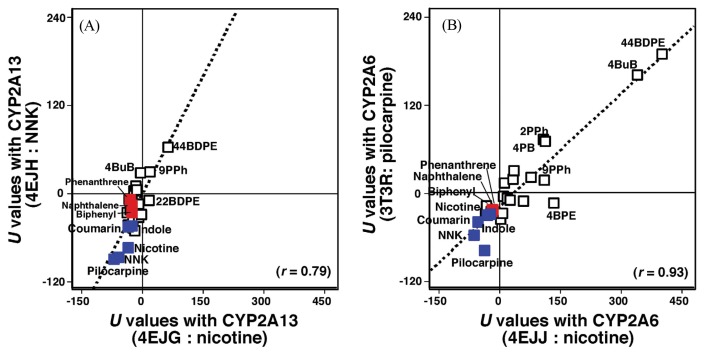

In order to examine structure-function relationships of the interactions of above 24 chemicals with active sites of CYP2A13 and CYP2A6, we compared the U values obtained with CYP2A13 4EJG (nicotine type) and CYP2A13 4EJH (NNK type) (Fig. 8A) and CYP2A6 4EJJ (nicotine type) and CYP2A6 3T3R (pilocarpine type) (Fig. 8B) (30). There were good correlations between U values of CYP2A13 4EJG (nicotine-type) and 4EJH (NNK-type) (r = 0.79, p < 0.01) and of CYP2A6 4Ejj (nicotine-type) and 2A6 3T3R (pilocarpine-type) (r = 0.93, p < 0.01) with these 24 chemicals and also with NNK, indole, pilocarpine, and nicotine as standards for CYP2A substrates (Fig. 8) (140–144). It was also found that the parent compounds, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and biphenyl had U values comparable to those of NNK, indole, pilocarpine, nicotine, and coumarin (Fig. 8). The results support the usefulness of molecular docking analysis in understanding the basis of molecular interaction of xenobiotic chemicals with the active sites of P450 proteins and possibly other enzymes.

Fig. 8.

Correlations of ligand-interaction energies (U values) of interaction of 24 chemicals (and also NNK, indole, pilocarpine, nicotine, and coumarin) with crystal structures of CYP2A13 4EJG (nicotine-type) and 4EJH (NNK-type) (A) and of CYP2A6 4EJJ (nicotine-type) and 3T3R (pilocarpine-type) (B). Points obtained with naphthalene, phenanthrene, and biphenyl are shown in red, other 21 chemicals in open square, and coumarin, indole, NNK, nicotine, and pilocarpine in blue. Abbreviations used in this figure: 4-biphenyl propargyl ether (4BPE), 9-(1-propynyl)phenanthrene (9PPh), 4-butynylbiphenyl (4BuB), 2,2′-biphenyl dipropargyl ether (22BDPE), and 4,4′-biphenyl dipropargyl ether (44BDPE). Data are taken from Shimada et al. (30) with modification.

Very recently, we carried out in vitro studies if these chemicals that interact with and inhibit CYP2A13 and 2A6 are oxidized by these enzymes (26,28–31). The results obtained showed that CYP2A13 is the major enzyme in 1-hydroxylation of pyrene, 8-hydroxylation of 1-hydroxypyrene (to form 1,8-dihydroxypyrene), hydroxylation of 1-nitropyrene and 1-actylpyrene (26). CYP2A13 also oxidized naphthalene, phenanthrene, and biphenyl to 1-naphthol, 9-hydroxyphenanthrene, and 2- and/or 4-hydroxybiphenyl, respectively (30). Our results also showed that acetylenic PAH compounds such as 2-ethynylnaphthalene, 1-naphthalene ethyl propargyl ether, 2-naphthalene propargyl ether, 2-ethynylphenanthrene, 3-ethynylphenanthrene, 2-(1-propynyl)phenanthrene, 3-(1-propynyl)phenanthrene, and 4-biphenyl propargyl ether which interact highly with CYP2A13 were found to be metabolized by this enzyme (30). In contrast, 2,5,2′,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl was found to be oxidized by CYP2A6 to form 4-hydroxylated metabolite at a much higher rate than by CYP2A13 (31).

Inhibition of human P450s by chemopreventive organoselenium compounds

We have previously shown that BSC and o-, m-, and p-XSC induce reverse type I binding spectra with CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 and inhibit EROD activities catalyzed by these P450 enzymes (81). The affinities of four selenium compounds in interactions with P450 family 1 enzymes were not very different; the Ks values obtained in the spectral interactions of four selenium compounds with CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 were 19~30 μM, 6.3~ 13 μM, and 3.6~5.7 μM, respectively, and the IC50 values for these chemicals were 0.10~0.45 μM for CYP1A1, 0.20~ 1.3 μM for CYP1A2, and 0.13~0.27 μM for CYP1B1 (Table 4). However, these organoselenium compounds were found to have relatively higher affinities for CYP1B1 than CYP1A1 and 1A2, because the Ks values in CYP1B1 were lower and the ΔAmax/Ks values in CYP1B1 were higher than those in the cases of the latter two enzymes (81).

Table 4.

Inhibition of CYP1A1-, 1A2, and 1B1-dependent EROD activities and CYP2A6- and 2A13-dependent coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities by organoselenium compounds

| (Chemical) (P450) | BSC | o-XSC | m-XSC | p-XSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| IC50 (μM) for inhibition of EROD activity | ||||

| CYP1A1 | 0.45 ± 0.038 | 0.11 ± 0.021 | 0.10 ± 0.013 | 0.26 ± 0.031 |

| CYP1A2 | 1.3 ± 0.22 | 0.39 ± 0.042 | 0.20 ± 0.021 | 0.63 ± 0.059 |

| CYP1B1 | 0.27 ± 0.031 | 0.14 ± 0.027 | 0.13 ± 0.011 | 0.16 ± 0.009 |

|

| ||||

| (Chemical) (P450) | BSC | o-XSC | m-XSC | p-XSC |

|

| ||||

| IC50 (μM) for inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylation activity | ||||

|

| ||||

| CYP2A6 | 4.3 ± 0.36 | 2.7 ± 0.34 | 2.4 ± 0.19 | 6.2 ± 0.55 |

| CYP2A13 | 1.2 ± 0.19 | 1.2 ± 0.13 | 0.22 ± 0.031 | 1.4 ± 0.21 |

IC50 values were obtained by measuring EROD activities for CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 and coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities for CYP2A6 and 2A13. Data for IC50 values represent means ± SE. Data are taken from from Shimada et al. (25) with modification.

These four organoselenium compounds also induce type I binding spectra with CYP2A13 and 2A6 and are able to inhibit coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities by these enzymes (Table 4) (25). We concluded that i) four selenium compounds bind to CYP2A6 and 2A13 to induce type I binding spectra (25), ii) both CYP2A13 and 2A6-dependent coumarin 7-hydroxylation activities are significantly inhibited by these selenium compounds (Table 4), and iii) the spectral changes and catalytic inhibition by these chemicals are more profoundly observed with CYP2A13 than CYP2A6 (25). Other human P450 enzymes, such as CYP2C9, 2E1, and 3A4, do not show any apparent spectral changes with these selenium compounds tested. Thus, one of the mechanisms underlying prevention of cancers caused by PAHs and tobacco-related carcinogens with these selenium compounds is suggested to be due to the results of inhibition of P450 family 1 and 2A enzymes.

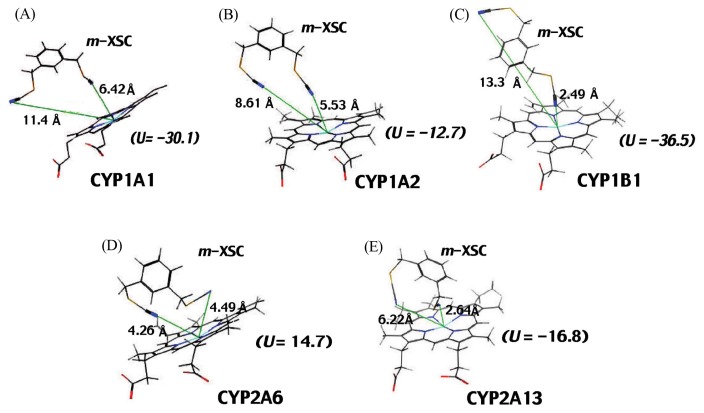

Molecular docking analysis was done to see interaction of m-XSC with CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, and 2A13 (Fig. 9). The distances between the N-atom in one of the -CH2SeCN moieties of m-XSC and the Fe-atom in CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 were calculated in silico analysis. By comparing the distances in CYP1A1, 1A2, and 1B1, it was found that one of the selenium moieties was closely oriented in the active sites of CYP1B1 (2.49 Å); these distances were 5.53 Å and 6.42 Å in CYP1A1 and 1A2, respectively. In contrast to the cases in P450 family 1 enzymes, both selenium moieties at 1- and 3-positions of m-XSC were docked near the heme of CYP2A13 and 2A6 (25). The distance between N-atom of m-XSC and the Fe-atom of CYP2A13 (2.64 Å) (Fig. 9C) was also close as compared with CYP2A6 (4.26 or 4.49 Å) (Fig. 9D, 9E).

Fig. 9.

Molecular docking analysis of interaction of m-XSC with CYP1A1 (A), 1A2 (B), 1B1 (C), 2A6 (D), and 2A13 (E). The ligand-P450 interaction energies (U values) and distances between the N-atom in one of the -CH2SeCN moieties of m-XSC and the Fe-atom (calculated using in silico analysis) in these P450s are shown in the figure.

CONCLUSIONS

Mouse Cyp1b1 and 2a5 have been shown to be important enzymes in initiating cell transformation caused by environmental carcinogens such as 7,12-DMBA, B[a]P, DB[a,l]P, and NNK based on the effects of disruption of respective P450 genes and specific chemical P450 inhibitors on the suppression of tumor formation caused by carcinogens in vivo. Because human CYP1B1 (and also CYP1A1 and 1A2) and CYP2A13 (and CYP2A6) have been shown to be the major enzymes involved in the activation of these carcinogenic PAHs and tobacco-related nitrosamines in vitro, it is interesting to determine what kinds of xenobiotic chemicals inhibit individual forms of human P450 enzymes. In this review, we have described the nature of various xenobiotic chemicals that inhibit human CYP1 and 2A enzymes; these chemicals include carcinogenic and non- or weak carcinogenic PAHs, arylacetylenes, plant flavonoid derivatives, organoselenium compounds, and other chemicals. Many chemical inhibitors induce type I, type II, and reverse type I spectral changes with specific form(s) of P450 and these spectral intensities often, but not all, relate to the abilities to inhibit and/or to be metabolized by these P450 enzymes. Molecular docking analysis is a useful tool in examining the interactions of chemical inhibitors with P450 enzymes and determining how these chemicals are metabolized by P450 enzymes. Dietary consumption of chemical inhibitors for P450 enzymes and polymorphisms of various P450 genes may affect differences in cancer susceptibilities caused by a variety of environmental carcinogens in humans.

Acknowledgments

ACKOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Drs. Masayuki Komori and Shigeo Takenaka (Osaka Prefecture University) for their support, Dr. F. Peter Guengerich (Vanderbilt University) for his support and collaboration for about 33 years, and Drs. Hiroshi Yamazaki and Norie Murayama (Showa Pharmaceutical University) for their useful advise and collaboration. Thanks are also due to Drs. Maryam K. Forrozesh (Xavier University of Louisiana), Donghak Kim (Konkuk University), and Kensaku Kakimoto (Osaka Prefectural Institute of Public Health) for their fruitful collaboration.

Abbreviations

- P450 or CYP

cytochrome P450

- EROD

7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation

- PAH

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

- B[a]P

benzo[a]pyrene

- B[e]P

benzo[e]pyrene

- 3-MC

3-methylcholanthrene

- 7,12-DMBA

7,12-dimethybenzo[a]anthracene

- DB[a,l]P

dibenzo[a,l]pyrene (or dibenzo[def,p]chrysene)

- ANF

α-naphthoflavone, NNK, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- Trp-P-1

3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole

- Trp-P-2

3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole

- 1PP

1-(1-propynyl)pyrene

- 1EP

1-ethynylpyrene

- 4EP

4-ethynylpyrene

- 4Pbi

4-propynyl biphenyl

- BSC

benzyl selenocyanate

- o-, m-, and p-XSC

1,2-phenylenebis( methylene)selenocyanate, 1,3-phenylenebis(methylene)selenocyanate, 1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)selenocyanate, respectively

Footnotes

Portion of this work has been presented at “Progress in Studies on the Antimutagenicity and Anticarcinogenicity” in the 32th Annual Meeting of KSOT/KEMS (November 3–4, 2016, Seoul, Korea).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rendic S, Guengerich FP. Contributions of human enzymes in carcinogen metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:1316–1383. doi: 10.1021/tx300132k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guengerich FP. Roles of cytochrome P-450 enzymes in chemical carcinogenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2946–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelkonen O, Nebert DW. Metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: etiologic role in carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 1982;34:189–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalas JR, Hecht SS, Murphy SE. Cytochrome P450 enzymes as catalysts of metabolism of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, a tobacco specific carcinogen. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:95–110. doi: 10.1021/tx049847p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue W, Warshawsky D. Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:73–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guengerich FP, Shimada T. Oxidation of toxic and carcinogenic chemicals by human cytochrome P-450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4:391–407. doi: 10.1021/tx00022a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carcinogens by cytochrome P450 1A1 and 1B1. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada T. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes involved in activation and inactivation of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2006;21:257–276. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.21.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada T, Okuda Y. Metabolic activation of environmental carcinogens and mutagens by human liver microsomes. Role of cytochrome P-450 homologous to a 3-methylcholanthrene-inducible isozyme in rat liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:459–465. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Evidence for cytochrome P-450NF, the nifedipine oxidase, being the principal enzyme involved in the bioactivation of aflatoxins in human liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:462–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada T, Iwasaki M, Martin MV, Guengerich FP. Human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the bioactivation of procarcinogens detected by umu gene response in Salmonella typhimurium TA1535/pSK1002. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3218–3228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimada T, Martin MV, Pruess-Schwartz D, Marnett LJ, Guengerich FP. Roles of individual human cytochrome P-450 enzymes in the bioactivation of benzo(a)pyrene, 7,8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo(a)pyrene, and other dihydrodiol derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6304–6312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyama T, Yamano S, Guzelian PS, Gelboin HV, Gonzalez FJ. Five of 12 forms of vaccinia virusexpressed human hepatic cytochrome P450 metabolically activate aflatoxin B1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4790–4793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitada M, Taneda M, Ohta K, Nagashima K, Itahashi K, Kamataki T. Metabolic activation of aflatoxin B1 and 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]-quinoline by human adult and fetal livers. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2641–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimada T, Hayes CL, Yamazaki H, Amin S, Hecht SS, Guengerich FP, Sutter TR. Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P450 1B1. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada T, Yun CH, Yamazaki H, Gautier JC, Beaune PH, Guengerich FP. Characterization of human lung microsomal cytochrome P-450 1A1 and its role in the oxidation of chemical carcinogens. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:856–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamazaki H, Inui Y, Yun CH, Guengerich FP, Shimada T. Cytochrome P450 2E1 and 2A6 enzymes as major catalysts for metabolic activation of N-nitrosodialkylamines and tobacco-related nitrosamines in human liver microsomes. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1789–1794. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.10.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita K, Kamataki T. Role of human cytochrome P450 (CYP) in the metabolic activation of N-alkylnitrosamines: application of genetically engineered Salmonella typhimurium YG7108 expressing each form of CYP together with human NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Mutat Res. 2001;483:35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada T, Oda Y, Gillam EM, Guengerich FP, Inoue K. Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other procarcinogens by cytochromes P450 1A1 and P450 1B1 allelic variants and other human cytochromes P450 in Salmonella typhimurium NM2009. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1176–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 1A1-, 1A2-, and 1B1-mediated activation of procarcinogens to genotoxic metabolites by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:288–294. doi: 10.1021/tx050291v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada T, Murayama N, Okada K, Funae Y, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP. Different mechanisms of inhibition for human cytochrome P450 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 by polycyclic aromatic inhibitors. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:489–496. doi: 10.1021/tx600299p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada T, Murayama N, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Imai Y, Hopkins NE, Foroozesh MK, Alworth WL, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Interaction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with human cytochrome P450 1B1 in inhibiting catalytic activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:2313–2323. doi: 10.1021/tx8002998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimada T, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Foroozesh MK, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Reverse type I binding spectra of human cytochrome P450 1B1 induced by flavonoid, stilbene, pyrene, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and biphenyl derivatives that inhibit catalytic activity: a structure-function relationship study. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1325–1333. doi: 10.1021/tx900127s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada T, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Murayama N, Martin MV, Foroozesh MK, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Structure-function relationships of inhibition of human cytochromes P450 1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2C9, and 3A4 by 33 flavonoid derivatives. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1921–1935. doi: 10.1021/tx100286d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada T, Murayama N, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Guengerich FP, Yamazaki H, Komori M. Spectral modification and catalytic inhibition of human cytochromes P450 1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, and 2A13 by four chemopreventive organoselenium compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1327–1337. doi: 10.1021/tx200218u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada T, Kim D, Murayama N, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Nagy LD, Folkman LM, Foroozesh MK, Komori M, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP. Binding of diverse environmental chemicals with human cytochromes P450 2A13, 2A6, and 1B1 and enzyme inhibition. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:517–528. doi: 10.1021/tx300492j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimada T, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Komori M, Kim D, Guengerich FP. Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and aryl and heterocyclic amines by human cytochromes P4502A13 and 2A6. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:529–537. doi: 10.1021/tx3004906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada T, Takenaka S, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Kim JH, Kim D, Yoshimoto FK, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Oxidation of acenaphthene and acenaphthylene by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2015;28:268–278. doi: 10.1021/tx500505y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada T, Takenaka S, Murayama N, Kramlinger VM, Kim JH, Kim D, Liu J, Foroozesh MK, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Oxidation of pyrene, 1-hydroxypyrene, 1-nitropyrene and 1-acetylpyrene by human cytochrome P450 2A13. Xenobiotica. 2016;46:211–224. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2015.1069419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada T, Takenaka S, Kakimoto K, Murayama N, Lim YR, Kim D, Foroozesh MK, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Structure-function studies of naphthalene, phenanthrene, biphenyl, and their derivatives in interaction with and oxidation by cytochromes P450 2A13 and 2A6. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29:1029–1040. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimada T, Kakimoto K, Takenaka S, Koga N, Uehara S, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Kim D, Guengerich FP, Komori M. Roles of human CYP2A6 and monkey CYP2A24 and 2A26 cytochrome P450 enzymes in the oxidation of 2,5,2′,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl. Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44:1899–1909. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.072991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buters JT, Sakai S, Richter T, Pineau T, Alexander DL, Savas U, Doehmer J, Ward JM, Jefcoate CR, Gonzalez FJ. Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 determines susceptibility to 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced lymphomas. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buters J, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Schober W, Soballa VJ, Hintermair J, Wolff T, Gonzalez FJ, Greim H. CYP1B1 determines susceptibility to low doses of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced ovarian cancers in mice: correlation of CYP1B1-mediated DNA adducts with carcinogenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:327–334. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buters JT, Mahadevan B, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Gonzalez FJ, Greim H, Baird WM, Luch A. Cytochrome P450 1B1 determines susceptibility to dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-induced tumor formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1127–1135. doi: 10.1021/tx020017q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buters JT, Mahadevan B, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Gonzalez FJ, Greim H, Baird WM, Luch A. Cytochrome P450 1B1 determines susceptibility to dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-induced tumor formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1127–1135. doi: 10.1021/tx020017q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddens LK, Bunde KL, Harper TA, Jr, McQuistan TJ, Löhr CV, Bramer LM, Waters KM, Tilton SC, Krueger SK, Williams DE, Baird WM. Cytochrome P450 1b1 in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-induced skin carcinogenesis: Tumorigenicity of individual PAHs and coal-tar extract, DNA adduction and expression of select genes in the Cyp1b1 knockout mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;287:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidel SM, Holston K, Buters JT, Gonzalez FJ, Jefcoate CR, Czupyrynski CJ. Bone marrow stromal cell cytochrome P4501B1 is required for pre-B cell apoptosis induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1317–1323. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heidel SM, MacWilliams PS, Baird WM, Dashwood WM, Buters JT, Gonzalez FJ, Larsen MC, Czuprynski CJ, Jefcoate CR. Cytochrome P4501B1 mediates induction of bone marrow cytotoxicity and preleukemia cells in mice treated with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3454–3460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J, Lauer FT, Dunaway S, Burchiel SW. Cytochrome P450 1B1 is required for 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)-anthracene (DMBA) induced spleen cell immunotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86:68–74. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyata M, Kudo G, Lee YH, Yang TJ, Gelboin HV, Fernandez-Salguero P, Kimura S, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the microsomal epoxide hydrolase gene. Microsomal epoxide hydrolase is required for the carcinogenic activity of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23963–23968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu Y, Nakatsuru Y, Ichinose M, Takahashi Y, Kume H, Mimura J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Ishikawa T. Benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenicity is lost in mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:779–782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luch A, Schober W, Soballa VJ, Raab G, Greim H, Jacob J, Doehmer J, Seidel A. Metabolic activation of dibenzo[a]pyrene by human cytochrome P450 1A1 and P450 1B1 expressed in V79 Chinese hamster cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:353–364. doi: 10.1021/tx980240g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimada T, Gillam EM, Oda Y, Tsumura F, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Inoue K. Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene to trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene by recombinant human cytochrome P450 1B1 and purified liver epoxide hydrolase. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:623–629. doi: 10.1021/tx990028s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uno S, Dalton TP, Derkenne S, Curran CP, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Nebert DW. Oral exposure to benzo[a]pyrene in the mouse: detoxication by inducible cytochrome P450 is more important than metabolic activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1225–1237. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uno S, Dalton TP, Dragin N, Curran CP, Derkenne S, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Gonzalez FJ, Nebert DW. Oral benzo[a]pyrene in Cyp1 knockout mice lines: CYP1A1 important in detoxication, CYP1B1 metabolism required for immune damage independent of total-body burden and clearance rate. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1103–1114. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nebert DW, Shi Z, Gálvez-Peralta M, Uno S, Dragin N. Oral benzo[a]pyrene: understanding pharmacokinetics, detoxication, and consequences--Cyp1 knockout mouse lines as a paradigm. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:304–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.086637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Megaraj V, Zhou X, Xie F, Liu Z, Yang W, Ding X. Role of CYP2A13 in the bioactivation and lung tumorigenicity of the tobacco-specific lung procarcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone: in vivo studies using a CYP2A13-humanized mouse model. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:131–137. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Z, Megaraj V, Li L, Sell S, Hu J, Ding X. Suppression of pulmonary CYP2A13 expression by carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis in a CYP2A13-humanized mouse model. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:698–702. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollander MC, Zhou X, Maier CR, Patterson AD, Ding X, Dennis PA. A Cyp2a polymorphism predicts susceptibility to NNK-induced lung tumorigenesis in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1279–1284. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L, Megaraj V, Wei Y, Ding X. Identification of cytochrome P450 enzymes critical for lung tumorigenesis by the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK): insights from a novel Cyp2abfgs-null mouse. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2584–2591. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou X, D’Agostino J, Xie F, Ding X. Role of CYP2A5 in the bioactivation of the lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:233–241. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.190173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang JS, Wanibuchi H, Morimura K, Gonzalez FJ, Fukushima S. Role of CYP2E1 in diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11141–11146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gelboin HV, Wiebel F, Diamond L. Dimethylbenzanthracene tumorigenesis and aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase in mouse skin: inhibition by 7,8-benzoflavone. Science. 1970;170:169–171. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3954.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kinoshita N, Gelboin HV. Aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase and polycyclic hydrocarbon tumorigenesis: effect of the enzyme inhibitor 7,8-benzoflavone on tumorigenesis and macromolecule binding. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:824–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.4.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinoshita N, Gelboin HV. The role of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene skin tumorigenesis: on the mechanism of 7,8-benzoflavone inhibition of tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1972;32:1329–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slaga TJ, Thompson S, Berry DL, Digiovanni J, Juchau MR, Viaje A. The effects of benzoflavones on polycyclic hydrocarbon metabolism and skin tumor initiation. Chem Biol Interact. 1977;3:297–312. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(77)90093-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riegel B, Wartman WB, Hill WT, Reeb BB, Shubik P, Stanger DW. Delay of methylcholanthrene skin carcinogenesis in mice by 1,2,5,6-dibenzofluorene. Cancer Res. 1951;11:301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill WT, Stanger DW, Pizzo A, Riege B, Shubik P, Wartman WB. Inhibition of 9,10-dimethyl-1,2-benzanthracene skin carcinogenesis in mice by polycyclic hydrocarbons. Cancer Res. 1951;11:892–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slaga TJ, Jecker L, Bracken WM, Weeks CE. The effects of weak or non-carcinogenic polycyclic hydrocarbons on 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene skin tumor-initiation. Cancer Lett. 1979;7:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(79)80076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DiGiovanni J, Rymer J, Slaga TJ, Boutwell RK. Anticarcinogenic and cocarcinogenic effects of benzo[e]pyrene and dibenz[a,c]anthracene on skin tumor initiation by polycyclic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:371–375. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smolarek TA, Baird WM. Benzo(e)pyrene-induced alterations in the stereoselectivity of activation of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene to DNA-binding metabolites in hamster embryo cell cultures. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1170–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smolarek TA, Baird WM, Fisher EP, DiGiovanni J. Benzo(e)pyrene-induced alterations in the binding of benzo(a)pyrene and 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene to DNA in Sencar mouse epidermis. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3701–3706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smolarek TA, Baird WM. Benzo[e]pyrene-induced alterations in the binding of benzo[a]pyrene to DNA in hamster embryo cell cultures. Carcinogenesis. 1984;8:1065–1069. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.8.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baird WM, Salmon CP, Diamond L. Benzo(e)pyrene-induced alterations in the metabolic activation of benzo(a)pyrene and 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene by hamster embryo cells. Cancer Res. 1984;44:1445–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lesca P, Mansuy D. 9-Hydroxyellipticine: inhibitory effect on skin carcinogenesis induced in Swiss mice by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Chem Biol Interact. 1980;30:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(80)90124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alworth WL, Viaje A, Sandoval A, Warren BS, Slaga TJ. Potent inhibitory effects of suicide inhibitors of P450 isozymes on 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene initiated skin tumors. Carcinogenesis. 1991;7:1209–1215. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.7.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cai Y, Baer-Dubowska W, Ashwood-Smith M, DiGiovanni J. Inhibitory effects of naturally occurring coumarins on the metabolic activation of benzo[a]pyrene and 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in cultured mouse keratinocytes. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:215–222. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kleiner HE, Vulimiri SV, Reed MJ, Uberecken A, DiGiovanni J. Role of cytochrome P450 1a1 and 1b1 in the metabolic activation of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and the effects of naturally ocurring furanocoumarins on skin tumor intitiation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:226–235. doi: 10.1021/tx010151v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kleiner HE, Reed MJ, DiGiovanni J. Naturally occurring coumarins inhibit human cytochromes P450 and block benzo[a]pyrene and 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene DNA adduct formation in MCF-7 cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:415–422. doi: 10.1021/tx025636d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sulfikkarali N, Krishnakumar N, Manoharan S, Nirmal RM. Chemopreventive efficacy of naringenin-loaded nanoparticles in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced experimental oral carcinogenesis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2013;19:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s12253-012-9581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silvan S, Manoharan S, Baskaran N, Anusuya C, Karthikeyan S, Prabhakar MM. Chemopreventive potential of apigenin in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced experimental oral carcinogenesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kassie F, Anderson LB, Scherber R, Yu N, Lahti D, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. Indole-3-carbinol inhibits 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone plus benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice and modulates carcinogen-induced alterations in protein levels. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6502–6511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanaka T, Makita H, Kawabata K, Mori H, Kakumoto M, Satoh K, Hara A, Sumida T, Tanaka T, Ogawa H. Chemoprevention of azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis by the naturally occurring flavonoids, diosmin and hesperidin. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:957–965. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takeuchi H, Saoo K, Matsuda Y, Yokohira M, Yamakawa K, Zeng Y, Kuno T, Kamataki T, Imaida K. 8-Methoxypsoralen, a potent human CYP2A6 inhibitor, inhibits lung adenocarcinoma development induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in female A/J mice. Mol Med Rep. 2009;2:585–588. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takeuchi H, Saoo K, Yokohira M, Ikeda M, Maeta H, Miyazaki M, Yamazaki H, Kamataki T, Imaida K. Pretreatment with 8-methoxypsoralen, a potent human CYP2A6 inhibitor, strongly inhibits lung tumorigenesis induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in female A/J mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7581–7583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miyazaki M, Yamazaki H, Takeuchi H, Saoo K, Yokohira M, Masumura K, Nohmi T, Funae Y, Imaida K, Kamataki T. Mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of 8-methoxypsoralen against 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced mouse lung adenomas. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1947–1955. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takeuchi H, Saoo K, Matsuda Y, Yokohira M, Yamakawa K, Zeng Y, Miyazaki M, Fujieda M, Kamataki T, Imaida K. Dose dependent inhibitory effects of dietary 8-methoxypsoralen on NNK-induced lung tumorigenesis in female A/J mice. Cancer Lett. 2006;234:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wattenberg LW. Inhibitory effects of benzyl isothiocyanate administered shortly before diethylnitrosamine or benzo[a]pyrene on pulmonary and forestomach neoplasia in A/J mice. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:1971–1973. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.12.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morse MA, Eklind KI, Amin SG, Hecht SS, Chung FL. Effects of alkyl chain length on the inhibition of NNK-induced lung neoplasia in A/J mice by arylalkyl isothiocyanates. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1757–1759. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.9.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morse MA, Amin SG, Hecht SS, Chung FL. Effects of aromatic isothiocyanates on tumorigenicity, O6-methylguanine formation, and metabolism of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in A/J mouse lung. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2894–2897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shimada T, El-Bayoumy K, Upadhyaya P, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Yamazaki H. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450-catalyzed oxidations of xenobiotics and procarcinogens by synthetic organoselenium compounds. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4757–4764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fiala ES, Joseph C, Sohn OS, El-Bayoumy K, Reddy BS. Mechanism of benzylselenocyanate inhibition of azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in F344 rats. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2826–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.von Weymarn LB, Chun JA, Hollenberg PF. Effects of benzyl and phenethyl isothiocyanate on P450s 2A6 and 2A13: potential for chemoprevention in smokers. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:782–790. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El-Bayoumy K, Chae YH, Upadhyaya P, Meschter C, Cohen LA, Reddy BS. Inhibition of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced tumors and DNA adduct formation in the mammary glands of female Sprague-Dawley rats by the synthetic organoselenium compound, 1,4-phenylenebis( methylene)selenocyanate. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2402–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prokopczyk B, Cox JE, Upadhyaya P, Amin S, Desai D, Hoffmann D, El-Bayoumy K. Effects of dietary 1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)selenocyanate on 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced DNA adduct formation in lung and liver of A/J mice and F344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:749–753. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prokopczyk B, Rosa JG, Desai D, Amin S, Sohn OS, Fiala ES, El-Bayoumy K. Chemoprevention of lung tumorigenesis induced by a mixture of benzo(a)pyrene and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone by the organoselenium compound 1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)selenocyanate. Cancer Lett. 2000;161:35–46. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(00)00590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.El-Bayoumy K, Das A, Boyiri T, Desai D, Sinha R, Pittman B, Amin S. Comparative action of 1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)selenocyanate and its metabolites against 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-DNA adduct formation in the rat and cell proliferation in rat mammary tumor cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;146:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.El-Bayoumy K, Sinha R, Pinto JT, Rivlin RS. Cancer chemoprevention by garlic and garlic-containing sulfur and selenium compounds. J Nutr. 2006;136:864S–869S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.864S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.El-Bayoumy K. Effects of organoselenium compounds on induction of mouse forestomach tumors by benzo(a)pyrene. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3631–3635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pelkonen O, Turpeinen M, Hakkola J, Honkakoski P, Hukkanen J, Raunio H. Inhibition and induction of human cytochrome P450 enzymes: current status. Arch Toxicol. 2008;82:667–715. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pelkonen O, Mäenpää J, Taavitsainen P, Rautio A, Raunio H. Inhibition and induction of human cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:1203–1253. doi: 10.1080/004982598238886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fowler S, Zhang H. In vitro evaluation of reversible and irreversible cytochrome P450 inhibition: current status on methodologies and their utility for predicting drug-drug interactions. AAPS J. 2008;10:410–424. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9042-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hisaka A, Ohno Y, Yamamoto T, Suzuki H. Prediction of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction caused by changes in cytochrome P450 activity using in vivo information. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:230–248. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Niwa T, Murayama N, Yamazaki H. Stereoselectivity of human cytochrome P450 in metabolic and inhibitory activities. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:549–569. doi: 10.2174/138920011795713724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang ZY, Wong YN. Enzyme kinetics for clinically relevant CYP inhibition. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:241–257. doi: 10.2174/1389200054021834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ansede JH, Thakker DR. High-throughput screening for stability and inhibitory activity of compounds toward cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:239–255. doi: 10.1002/jps.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kamel A, Harriman S. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes and biochemical aspects of mechanism-based inactivation (MBI) Drug Discov Today Technol. 2013;10:e177–e189. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Okino ST, Quattrochi LC, Barnes HJ, Osanto S, Griffin KJ, Johnson EF, Tukey RH. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs encoding 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-inducible rabbit mRNAs for cytochrome P-450 isozymes 4 and 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5310–5314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Quattrochi LC, Okino ST, Pendurthi UR, Tukey RH. Cloning and isolation of human cytochrome P-450 cDNAs homologous to dioxin-inducible rabbit mRNAs encoding P-450 4 and P-450 6. DNA. 1985;4:395–400. doi: 10.1089/dna.1985.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jaiswal AK, Nebert DW, Gonzalez FJ. Human P3(450): cDNA and complete amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6773–6774. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.16.6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sutter TR, Tang YM, Hayes CL, Wo YY, Jabs EW, Li X, Yin H, Cody CW, Greenlee WF. Complete cDNA sequence of a human dioxin-inducible mRNA identifies a new gene subfamily of cytochrome P450 that maps to chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13092–13099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sansen S, Yano JK, Reynald RL, Schoch GA, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. Adaptations for the oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exhibited by the structure of human P450 1A2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14348–14355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang A, Savas U, Stout CD, Johnson EF. Structural characterization of the complex between alphanaphthoflavone and human cytochrome P450 1B1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5736–5743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Walsh AA, Szklarz GD, Scott EE. Human cytochrome P4501A1structure and utility in understanding drug and xenobiotic metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12932–12943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang TK, Gonzalez FJ, Waxman DJ. Evaluation of triacetyloleandomycin, alpha-naphthoflavone and diethyldithiocarbamate as selective chemical probes for inhibition of human cytochromes P450. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:437–442. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koley AP, Buters JT, Robinson RC, Markowitz A, Friedman FK. Differential mechanisms of cytochrome P450inhibition and activation by alpha-naphthoflavone. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3149–3152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhai S, Dai R, Friedman FK, Vestal RE. Comparative inhibition of human cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2 by flavonoids. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:989–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu J, Sridhar J, Foroozesh M. Cytochrome P450 family 1 inhibitors and structure-activity relationships. Molecules. 2013;18:14470–14495. doi: 10.3390/molecules181214470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sridhar J, Liu J, Foroozesh M, Stevens CL. Insights on cytochrome p450 enzymes and inhibitors obtained through QSAR studies. Molecules. 2012;17:9283–9305. doi: 10.3390/molecules17089283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shimada T, Wunsch RM, Hanna IH, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Gillam EM. Recombinant human cytochrome P4501B1 expression in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;357:111–120. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shimada T, Gillam EM, Sutter TR, Strickland PT, Guengerich FP, Yamazaki H. Oxidation of xenobiotics by recombinant human cytochrome P4501B1. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Foroozesh M, Hopkins NE, Alworth WL, Guengerich FP. Selectivity of polycyclic inhibitors for human cytochrome P450s 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1048–1056. doi: 10.1021/tx980090+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rubin H. Synergistic mechanisms in carcinogenesis by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and by tobacco smoke: a bio-historical perspective with updates. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1903–1930. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Marston CP, Pereira C, Ferguson J, Fischer K, Hedstrom O, Dashwood WM, Baird WM. Effect of a complex environmental mixture from coal tar containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) on the tumor initiation, PAH-DNA binding and metabolic activation of carcinogenic PAH in mouse epidermis. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1077–1086. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mahadevan B, Parsons H, Musafia T, Sharma AK, Amin S, Pereira C, Baird WM. Effect of artificial mixtures of environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present in coal tar, urban dust, and diesel exhaust particulates on MCF-7 cells in culture. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:99–107. doi: 10.1002/em.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mahadevan B, Marston CP, Dashwood WM, Li Y, Pereira C, Baird WM. Effect of a standardized complex mixture derived from coal tar on the metabolic activation of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human cells in culture. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:224–231. doi: 10.1021/tx0497604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jarvis IW, Dreij K, Mattsson Å, Jernström B, Stenius U. Interactions between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in complex mixtures and implications for cancer risk assessment. Toxicology. 2014;321:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Foroozesh MK, Primrose G, Guo Z, Bell LC, Alworth WL, Guengerich FP. Aryl acetylenes as mechanism-based inhibitors of cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:91–102. doi: 10.1021/tx960064g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hopkins NE, Foroozesh MK, Alworth WL. Suicide inhibitors of cytochrome P450 1A1 and P450 2B1. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:787–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90417-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]