Abstract

Survey results showed treponemal infection among pet macaques in Southeast Asia, a region with a high prevalence of human yaws. This finding, along with studies showing treponemal infection in nonhuman primates in Africa, should encourage a One Health approach to yaws eradication and surveillance activities, possibly including monitoring of nonhuman primates in yaws-endemic regions.

Keywords: Treponema pallidum, Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue, Macaca spp., yaws, macaques, nonhuman primates, Asia, Southeast Asia, pets, Sulawesi, Indonesia, nontreponemal, bacteria, eradication, mammalian host reservoirs, One Health, surveillance

Yaws, an endemic tropical disease distinguished by bone and skin lesions, is caused by infection with Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue treponemes. Successful yaws treatment campaigns during 1950–1965 were followed by a resurgence of disease, and the World Health Organization (WHO) consequently mounted a yaws eradication campaign (1). Although the agent of yaws is spread among humans via direct contact, research has shown that nonhuman primates (NHPs) may serve as mammalian host reservoirs with the potential for zoonotic transmission (2). Successful eradication campaigns depend on there being no reservoir shielding the agent from eradication efforts; thus, the role that NHPs play in yaws among humans must be determined (3).

African Old World primates (OWPs) can be infected by T. pallidum and exhibit symptoms of yaws (2). Of note, the Treponema Fribourg-Blanc strain (isolated from a baboon in western Africa in 1966) exhibits remarkable genetic similarity to strains that cause yaws in humans (4) and in experiments, was shown capable of infecting humans (5). More recently, studies focusing on treponemal infections among NHPs in eastern Africa and the Republic of Congo showed that the NHP geographic range overlaps considerably with areas having a formerly high prevalence of yaws in humans (2).

Macaques (Macaca spp.), OWPs native to Asia and northern Africa, are susceptible to and have been experimentally infected with T. pallidum (6). After the initial WHO eradication efforts, yaws was believed to be largely eliminated from countries of mainland Asia, although reporting and active case detection have not been uniform throughout the region (7). Several island nations in Asia, however, continue to report active human yaws cases (8,9).

Macaques, the most widely distributed and numerous NHPs in the world, are sympatric with humans throughout Asia, thriving in human-altered environments and commonly kept as pets. To further characterize the role NHPs might play in the maintenance of T. pallidum subspecies, we screened an extensive archive of serum samples collected from free-ranging and captive macaques.

The Study

As part of a project characterizing the pathogen landscape among macaques and humans, we collected blood samples from NHPs during 1999–2012 and stored them at −80°C (10). We retrospectively screened samples from 734 macaques representing 13 species distributed throughout the animal’s natural geographic range (Table 1). Study protocols were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (no. 4233–01) and adhered to the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of NHPs (https://www.asp.org/society/resolutions/EthicalTreatmentOfNonHumanPrimates.cfm).

Table 1. Number and species of free-ranging and captive macaques tested for treponemal infection, by location, 2000–2014*.

| Country, species | Year(s) sampled | Total no. sampled | No. captive | No. free-ranging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nepal | 2003 | |||

|

Macaca mulatta

|

|

28 |

0 |

28 |

| Bangladesh | 2008–2012 | |||

|

M. mulatta

|

|

137 |

14 |

123 |

| Thailand | 2003 | |||

| M. arctoides | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| M. assamensis | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| M. fascicularis | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| M. mulatta | 9 | 9 | 0 | |

|

M. nemestrina

|

|

4 |

4 |

0 |

| Cambodia | 2011 | |||

| M. fascicularis | 39 | 0 | 39 | |

| M. leonina | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| M. nemestrina | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

|

M. spp. (hybrid)

|

|

3 |

0 |

3 |

| Singapore | 2003, 2005–2006, 2009 | |||

|

M. fascicularis

|

|

76 |

0 |

76 |

| Gibraltar | 2004, 2009, 2013–2014 | |||

|

M. sylvanus

|

|

124 |

0 |

124 |

| Indonesia | ||||

| Bali | 2000–2003 | |||

| M. fascicularis | 157 | 0 | 157 | |

| Java | 2002 | |||

| M. fascicularis | 25 | 25 | 0 | |

| Sulawesi | 2000–2002 | |||

| M. balantak | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| M. fascicularis | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| M. hecki | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| M. maura | 9 | 9 | 0 | |

| M. nemestrina | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| M. nigra | 22 | 14 | 8 | |

| M. nigrescens | 11 | 11 | 0 | |

| M. ochreata | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| M. tonkeana | 40 | 40 | 0 | |

|

Macaca spp. (hybrid) |

|

15 |

15 |

0 |

| Total | 2003–2014 | 734 | 170 | 564 |

*The 734 tested macaques represented 13 species. Captive category included pets, macaques used in performances, and macaques in zoos; free-ranging included wild macaques, urban macaques, and those at temples, shrines, and reserve parks.

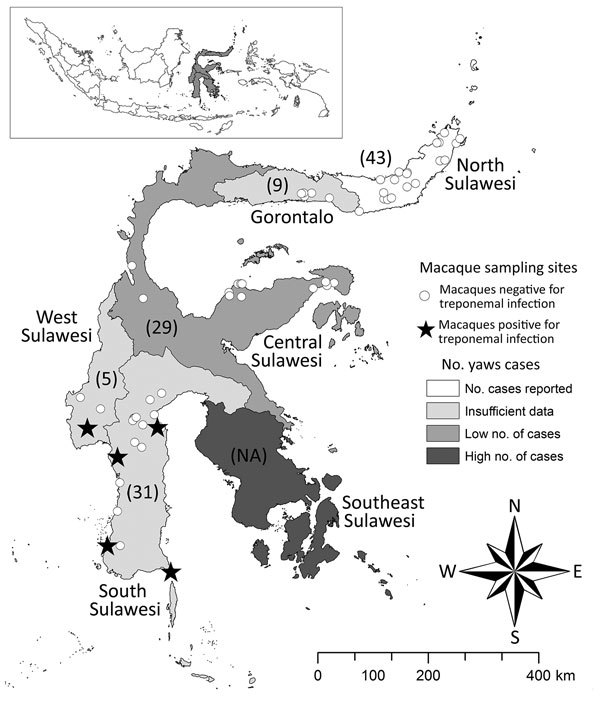

We used a Macro-Vue RPR Card Test Kit (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to screen the 734 blood samples; 11 (1.5%) were positive (Table 2). The RPR (rapid plasma reagin) test, a lipoidal test (nontreponemal) for IgG and IgM typically associated with treponemal infection, can occasionally elicit nonspecific responses. To confirm RPR-positive samples, we used ESPLINE TP (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan), an enzyme immunoassay for measuring reactivity to 2 recombinant T. pallidum antigens, Tp47 and Tp17. ESPLINE TP and RPR tests have been validated for use in OWPs (11). Of the 11 RPR test–positive samples, 1 was from Singapore; 2 from Bali, Indonesia; and 8 from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Six samples (all from Sulawesi) yielded confirmatory positive results on the ESPLINE TP assay. Of note, in Sulawesi, the only positive macaques were pets sampled from South Sulawesi and West Sulawesi Provinces, which make up the island’s southwestern peninsula (Figure). We also used ESPLINE TP to test the 28 RPR test–negative samples from Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula; none tested positive.

Table 2. Treponemal infections in blood samples from free-ranging and pet macaques, by geographic location, 1999–2012*.

| Location |

No. macaques positive/no. negative (% reactive)† |

No. macaques tested/no. positive‡ |

| Indonesia | ||

| Bali | 2/155 (1.3) | 2/0 |

| Java | 0/25 (0) | NA |

| Sulawesi |

8/109 (7.3) |

8/6 |

| Nepal |

0/28 (0) |

NA |

| Singapore |

1/75 (1.3) |

1/0 |

| Bangladesh |

0/137 (0) |

NA |

| Thailand |

0/22 (0) |

NA |

| Cambodia |

0/48 (0) |

NA |

| Gibraltar |

0/124 (0) |

NA |

| Total | 11/734 (1.5) | 11/0 |

*NA, indicates that samples in the region were not tested. †Determined by using the Macro-Vue RPR (rapid plasma reagin) test (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). ‡Determined by using ESPLINE TP (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan), a reagent for the detection of Treponema pallidum antibodies.

Figure.

Individual sampling sites where macaques were tested for infection with Treponema spp. during 1999–2012 and the number of human yaws cases during 2001–2011, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Numbers in parentheses indicate number nonhuman primates sampled in each of the 6 provinces. ESPLINE TP (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan) reagent for the detection of T. pallidum antibodies was used to determine whether macaque samples were positive for treponemal infection. The number of human yaws cases was determined by the World Health Organization (1). Inset map shows the location of Sulawesi in Indonesia (gray shading). NA, not available.

At the time of sampling, the macaques underwent a physical examination, including close inspection of head, trunk, extremities, oral cavity, and genitals. We conducted a retrospective review of the data and found that none of the macaques had lesions typical of treponemal infection (4). Of the 734 macaques, 13, including 2 seropositive macaques from Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula, had hypopigmentation on the palms of their hands, feet, or both. Hypopigmentation is rarely seen in yaws but is a common manifestation of pinta, which is caused by infection with T. carateum, a close relative of T. p. pertenue.

Conclusions

Our findings show that pet macaques in Southeast Asia can be infected with Treponema spp. related to those that infect humans. The overall prevalence of infection was low in our survey, but the pocket of infection detected among pets in Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula is noteworthy. The demonstration of reactivity in the serologic tests provides unequivocal evidence that the macaques had been infected with T. pallidum or a highly related pathogen. We had hoped to amplify a portion of tp0548, a locus in the T. pallidum genome used for molecular typing, but no amplifiable pathogen DNA was found in the whole-blood samples that had been held in storage for >10 years. Therefore, we could not determine whether the treponemal strains from NHPs in Sulawesi resembled strains that cause human yaws.

Sulawesi, the third largest island in the Indonesian archipelago, has a population of ≈17 million persons and 7 endemic macaque species. The seropositive samples from South Sulawesi and West Sulawesi Provinces were collected in July and August of 2000, immediately predating an active yaws outbreak among humans in the region that caused 241 documented cases in the neighboring southeastern peninsula during 2001–2011 (WHO, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75528/1/WHO_HTM_NTD_IDM_2012.2_eng.pdf) (Figure). During that outbreak, WHO characterized the South Sulawesi and West Sulawesi Provinces as “data deficient” regions in regard to the status of yaws among the human population. Most macaques whose samples were used in this study were free-ranging, but all of the macaques sampled in South Sulawesi and West Sulawesi Provinces had been captured at a young age for use as pets. The association between humans and pet macaques is often intimate, with the sharing of food; space; and physical contact through grooming, play, or aggression (12). Two of the Treponema spp.–infected pets were owned by the same person and housed together. Studies of pet macaques in Sulawesi and their owners have indicated that infectious agents can move between these populations (12,13). Although the treponemal serologic status of the pet owners in this study is unavailable, the fact that seropositive pet NHPs from a region neighboring an area with a high number of human yaws cases suggests that the NHP cases resulted from treponeme transmission from humans to pets.

All macaques in this study, with the exception of M. sylvanus from Gibraltar, were from historically yaws-endemic areas where WHO conducted past yaws eradication campaigns. Much of Asia has a rich tradition of human–NHP commensalism, and macaques are common in villages, often as pets (10). Moreover, we previously showed that macaques can harbor an array of mammalian picornaviruses, astroviruses, and mycobacteria (13–15), underscoring the role of macaques in the ecology of these pathogens. However, as with our current study of treponemal infections, definitive evidence for transmission and the direction of transmission have not been established for these pathogens.

Our findings of treponemal infections among macaques in Southeast Asia, along with published work showing infection in NHPs in Africa (4), should encourage holistic and One-Health approaches to eradication and surveillance activities, including consideration of monitoring NHPs in yaws-endemic regions. Such approaches are particularly relevant for pet NHPs, which can easily be assessed and treated. The human–NHP interface is ancient and complex, and continued research, particularly in yaws-endemic regions, can help to ameliorate concerns as a second WHO yaws eradication campaign moves forward.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to all of the communities, temple committees, and government agencies in the areas where we have been sampling monkeys for years: Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan, Indonesia; S. Chan and the staff of the Central Nature Reserve, National Parks Board, Singapore; M. Pizarro and the staff of the Gibraltar Ornithological and Natural History Society; S. Begum, M. K. Hasan, S. Akhtar, and the students and faculty of the Department of Zoology, Jahangirnagar University; and S. Son, C. Kimleng, S. Bunnary, T. Sothearos, M. Sisiket, H. Davun, and K. Pal in Cambodia and Nepal. We are also grateful to D. Cohn, A. Fuentes, J. Supriatna, R. Babo, Y. Paramastri, E. Iskandar, J. Froehlich, L. Engel, H. Engel, and L. Johnson for supporting and participating in this research.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant R01 AI078229 and R03 AI064865 to L.J.E.); National Center for Research Resources, NIH (grant P51 RR000166RR to L.J.E); US Public Health Services (grant R01 AI42143 to S.A.L.); Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (grant N66001-02-C-8072 to L.J.E.); University of Toronto Connaught Fund (M.S.); the Chicago Zoological Society (to L.J.E.); and University of New Mexico Research Allocations Committee (L.J.E.).

Biography

Dr. Klegarth is a postdoctoral research associate in the Evolutionary Emergence of Infectious Diseases Laboratory at the University of Washington. Her research is focused on human–wildlife conflict, with an emphasis on urban nonhuman primates, and the infectious agents that are transmitted at this interface.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Klegarth AR, Ezeonwu CA, Rompis A, Lee BP, Aggimarangsee N, Chalise M, et al. Survey of treponemal infections in free-ranging and captive macaques, 1999–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 May [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2305.161838

References

- 1.The World Health Organization. Eradication of yaws—the Morges strategy. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knauf S, Liu H, Harper KN. Treponemal infection in nonhuman primates as possible reservoir for human yaws. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:2058–60. 10.3201/eid1912.130863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks M, Mitjà O, Vestergaard LS, Pillay A, Knauf S, Chen CY, et al. Challenges and key research questions for yaws eradication. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1220–5. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00136-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zobaníková M, Strouhal M, Mikalová L, Cejková D, Ambrožová L, Pospíšilová P, et al. Whole genome sequence of the Treponema Fribourg-Blanc: unspecified simian isolate is highly similar to the yaws subspecies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2172. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JL, David NJ, Indgin S, Israel CW, Levine BM, Justice J Jr, et al. Neuro-ophthalmological study of late yaws and pinta. II. The Caracas project. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:226–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols HJ. Experimental yaws in the monkey and rabbit. J Exp Med. 1910;12:616–22. 10.1084/jem.12.5.616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahariya C, Pradhan SK. Can Southeast Asia eradicate yaws by 2010? Some lessons from the Yaws Eradication Programme of India. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitjà O, Marks M, Konan DJ, Ayelo G, Gonzalez-Beiras C, Boua B, et al. Global epidemiology of yaws: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e324–31. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00011-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Strych U, Chang LY, Lim YAL, Goodenow MM, et al. Neglected tropical diseases among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): overview and update. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003575. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones-Engel L, Steinkraus KA, Murray SM, Engel GA, Grant R, Aggimarangsee N, et al. Sensitive assays for simian foamy viruses reveal a high prevalence of infection in commensal, free-ranging Asian monkeys. J Virol. 2007;81:7330–7. 10.1128/JVI.00343-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knauf S, Dahlmann F, Batamuzi EK, Frischmann S, Liu H. Validation of serological tests for the detection of antibodies against Treponema pallidum in nonhuman primates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003637. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones-Engel L, Engel GA, Schillaci MA, Babo R, Froehlich J. Detection of antibodies to selected human pathogens among wild and pet macaques (Macaca tonkeana) in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Am J Primatol. 2001;54:171–8. 10.1002/ajp.1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilbur AK, Engel GA, Rompis A, A Putra IG, Lee BP, Aggimarangsee N, et al. From the mouths of monkeys: detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA from buccal swabs of synanthropic macaques. Am J Primatol. 2012;74:676–86. 10.1002/ajp.22022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberste MS, Feeroz MM, Maher K, Nix WA, Engel GA, Hasan KM, et al. Characterizing the picornavirus landscape among synanthropic nonhuman primates in Bangladesh, 2007 to 2008. J Virol. 2013;87:558–71. 10.1128/JVI.00837-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlsson EA, Small CT, Freiden P, Feeroz MM, Matsen FA IV, San S, et al. Non-human primates harbor diverse mammalian and avian astroviruses including those associated with human infections. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005225. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]