Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) has been shown to play important roles in maintaining β-cell functions, such as insulin secretion and proliferation. While expression levels of GLP-1 receptor (Glp1r) are compromised in the islets of diabetic rodents, it remains unclear when and to what degree Glp1r mRNA levels are decreased during the progression of diabetes. In this study, we performed real-time PCR with the islets of db/db diabetic mice at different ages, and found that the expression levels of Glp1r were comparable to those of the islets of nondiabetic db/misty controls at the age of four weeks, and were significantly decreased at the age of eight and 12 weeks. To investigate whether restored expression of Glp1r affects the diabetic phenotypes, we generated the transgenic mouse model Pdx1PB-CreER™; CAG-CAT-Glp1r (βGlp1r) that allows for induction of Glp1r expression specifically in β cells. Whereas the expression of exogenous Glp1r had no measurable effect on glucose tolerance in nondiabetic βGlp1r;db/misty mice, βGlp1r;db/db mice exhibited higher glucose and lower insulin levels in blood on glucose challenge test than control db/db littermates. In contrast, four weeks of treatment with exendin-4 improved the glucose profiles and increased serum insulin levels in βGlp1r;db/db mice, to significantly higher levels than those in control db/db mice. These differential effects of exogenous Glp1r in nondiabetic and diabetic mice suggest that downregulation of Glp1r might be required to slow the progression of β-cell failure under diabetic conditions.

Keywords: GLP-1 receptor, GLP-1, Diabetes, β Cell failure, Exendin-4

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a progressive and chronic metabolic disorder, in which the sustained elevation of blood glucose levels leads to serious complications, such as blindness, kidney failure, etc. As all types of diabetes result from the absolute or relative deficiency of insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells [1], it is a potential target of therapies to protect or improve the damaged β cells [2].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a peptide secreted from enteroendocrine L cells in the gut, is known to exert its insulinotropic actions through GLP-1 receptors expressed in pancreatic β cells. In vivo and in vitro studies with GLP-1 and its analogs have revealed that GLP-1 not only potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), but also increases insulin synthesis, stimulates β cell proliferation/neogenesis, and inhibits β cell apoptosis [3]. Although clinical studies demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor agonists improved glycemic controls in diabetic patients accompanied by increased insulin secretion [4], this class of medications is not always effective for diabetic patients and residual β-cell function may be associated with the efficacy of this treatment [5] [6] [7] [8].

Recently it has been reported that the expression levels of GLP-1 receptor (Glp1r) were reduced not only in the islets of rodent diabetic models, such as pancreatectomized rats and diabetic db/db mice [9] [10], but also in the islets of human diabetic patients [11] [12]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the decreased expression of Glp1r is associated with the pathogenesis or progression of β-cell failure, and that sustained expression of Glp1r may improve the metabolic profiles of diabetic mice. In order to test our hypothesis, we generated a novel transgenic mouse model in which the expression of Glp1r is maintained specifically in β cells only after Cre-mediated recombination following tamoxifen treatment. Whereas exogenous Glp1r had no effect on metabolic profiles in nondiabetic mice, persistent expression of Glp1r under diabetic conditions in db/db mice resulted in further impaired β-cell function, but a significantly greater response to GLP-1 receptor agonist, suggesting that the persistent activation of GLP-1 signaling does not necessarily exert beneficial effects on β-cell function, and even worse can lead to the progression of β-cell failure under diabetic conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Obese diabetic C57BL/KsJ-db/db (db/db) male mice and nondiabetic C57BL/KsJ-db/misty (db/m) male mice were purchased from Japan SLC. Pdx1PB-CreER™ and CAG-CAT-Glp1r-IRES-eGFP (βGlp1r) transgenic mice were generated as described previously [13] [14]. The βGlp1r mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/KsJ background for more than 8 generations by crossing βGlp1r mice with C57B/KsJ-db/misty mice.

Tamoxifen (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was prepared at 20 mg/mL in corn oil and injected subcutaneously into βGlp1r mice and their littermates at 1.5 mg/10 g body weight twice every other day at the age of four weeks. To assess the effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist exendin-4, the mice were infused with exendin-4 at 24 nmol/kg body weight per day, or with volume-matched saline as controls, using a mini-osmotic pump (ALZET, model 1004, Cupertino, CA, USA), which delivers the solution at a constant rate for four weeks, from the age of six to 10 weeks.

Mice were housed on a 12-h light–dark cycle in a controlled climate. All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine.

2.2. RNA extraction and real-time PCR

To isolate the islets of db/m and db/db mice, collagenase (Liberase TL, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was injected into the pancreatic ducts. Isolated pancreata were digested in a 37 °C incubator for 20 min, shaken gently, and washed with 0.25 mol/L sucrose. Islets were handpicked under a dissection microscope.

Total RNA was extracted from isolated islets using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using WT-Ovation RNA Amplification System (Nugen, San Carlos, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Custom Arrays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The relative expression level for each gene was presented relative to the control mRNA level of β-glucuronidase (Gusb).

2.3. Measurement of metabolic parameters

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) were performed after 6-h fasting by oral administration of glucose (1.0 g/kg mouse body weight). Blood glucose levels and plasma insulin levels were measured using a portable glucose meter (Sanwa Kagaku Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) and insulin ELISA kit (Morinaga Institute of Biological Science, Yokohama, Japan), respectively. HbA1c levels were measured using a DCA Vantage analyzer (Siemens, Berlin, Germany).

2.4. Histology

Immunohistochemistry was performed for the observation of GFP-expressing cells, as described previously [14]. The primary antibodies used in this study were the following: guinea pig anti-insulin (1:1000; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), chicken anti-insulin (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-GFP (1:200; MBL, Nagoya, Japan), and anti-Ki67 (1:100; BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Insulin-positive area and total pancreas area were measured using a BZ-X analyzer (Keyence, Osaka, Japan), and β-cell mass was calculated as relative β-cell area multiplied by the pancreatic weight. For the detection of Ki67, mounted sections were microwaved at 95 °C for 20 min in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval, before being incubated with blocking serum. Slides were observed using an Olympus FV1000D confocal laser-scanning microscope. In order to detect apoptotic cells, TUNEL assay was performed using an apoptotic detection system (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or unpaired t test (two tailed). P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Age-dependent decrease in incretin receptor expression levels in db/db islets

While the expression level of GLP-1 receptor (Glp1r) was reported to be reduced in the islets of diabetic db/db mice at the age of 16 weeks, it has not yet been examined yet at earlier stages in the course of development of diabetes. To investigate age-dependent alterations in gene expression profiles for Glp1r and other pancreas-specific genes in db/db mice, TaqMan real-time PCR array was performed for 46 pancreas-specific genes in the islets of db/db diabetic and db/m nondiabetic mice, at four, eight, and 12 weeks of age. The expression levels of insulin 1 (Ins1) and insulin 2 (Ins2) in db/db mice were comparable to those in control (db/m) mice at the age of 4 and 8 weeks, and significantly decreased at 12 weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. 1), when fasting blood glucose levels rise above 250 mg/dL. There was no significant difference in glucagon (Gcg) and somatostatin (Sst) mRNA levels between db/m and db/db mice at least 12 weeks of age.

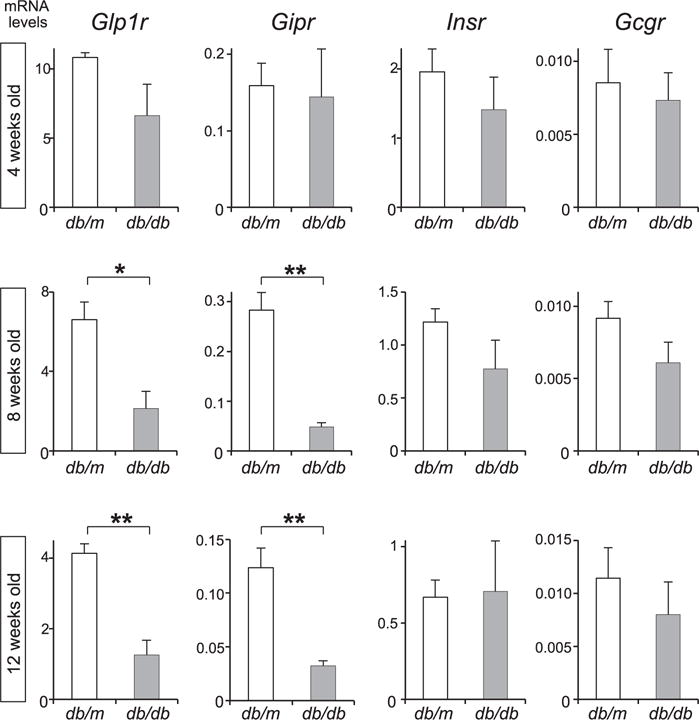

In contrast to the mRNA levels of endocrine hormones, those of Glp1r and GIP receptor (Gipr) were significantly decreased in db/db mice at the age of 8 weeks as well as 12 weeks (Fig. 1). Glp1r mRNA levels in db/db mice were less than one third of those in db/m mice at both ages. On the other hand, expression levels of insulin receptor (Insr) and glucagon receptor (Gcgr), which are highly expressed in adult β cells in mice, were comparable between db/db and db/m mice at all ages that were examined.

Fig. 1.

Age-dependent decrease in Glp1r expression levels in db/db mouse islets. Expression levels of incretin receptors and two other receptors. Islets were isolated from db/m and db/db mice at the age of four, eight, and 12 weeks, and TaqMan real-time PCR was performed. All expression levels were normalized to β-glucuronidase. *, p < 0.05.

Among the pancreas-specific transcription factors that are known to be expressed in adult endocrine cells, Mafa was substantially decreased in db/db islets, showing 90% and 87% reductions compared with db/m islets at the age of eight and 12 weeks, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). On the other hand, levels of Neurog3 mRNAs showed a 6-fold increase in the islets of db/db mice.

3.2. Generation of β-cell-specific Glp1r-overexpressing mice

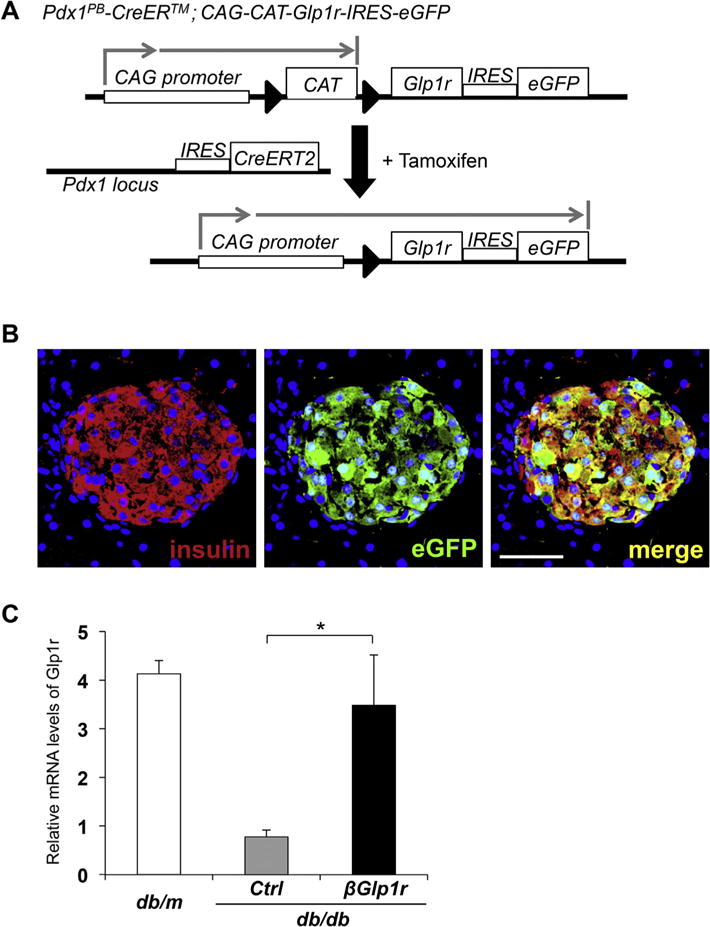

The robust reduction of Glp1r mRNAs during the progression of hyperglycemia led to the question as to whether the continuous expression of Glp1r in β cells could positively affect the metabolic profiles in this diabetic mouse model. To address this issue, we generated a novel transgenic mouse model, βGlp1r, in which the expression of Glp1r can be induced specifically in β cells. CAG-CAT-Glp1r-IRES-eGFP mice [14], which conditionally and specifically express Glp1r and eGFP by Cre-mediated recombination, were interbred with Pdx1PB-CreER™ transgenic mice that express tamoxifen-activated Cre recombinase under the control of the β-cell-specific Pdx1Area I/II enhancer [13]. The βGlp1r mice were crossed with C57BL/KsJ-db/misty (db/m) mice to generate both βGlp1r;db/m and βGlp1r;db/db. Because the eGFP reporter gene was placed downstream of the Glp1r cDNA via an IRES element (Fig. 2A), the exogenous Glp1r-expressing β cells in βGlp1r mice are lineage labeled as green-fluorescent cells.

Fig. 2.

Generation of transgenic mice that overexpress Glp1r in β cells. (A) A schematic representation of Pdx1PB-CreER™; CAG-CAT-Glp1r-IRES-eGFP and its recombination by Cre recombinase. Before recombination, the transcription of exogenous Glp1r is blocked by the floxed STOP cassette. When the mice are mated with Cre-expressing Pdx1PB- CreER™ mice, the floxed sequence is removed by Cre recombinase, and the CAG promoter can activate the expression of Glp1r. (B) βGlp1r; db/db mice were treated with tamoxifen at the age of four weeks, and sacrificed at the age of 10 weeks. Immunostaining with antibodies against insulin (red), eGFP (green), and DAPI (blue) demonstrated that all eGFP-expressing cells were positive for insulin. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C) βGlp1r;db/db mice and control littermates were treated with tamoxifen at the age of four weeks, and the islets were isolated at 12 weeks of age. The expression levels of Glp1r were quantified by TaqMan PCR. *, p < 0.05; n = 4.

When βGlp1r;db/db mice were treated with tamoxifen at the age of four weeks and sacrificed one week later, immunostaining against eGFP and insulin revealed that all eGFP-expressing cells were positive for insulin and 72.5% ± 8.4% of insulin-expressing cells were positive for eGFP (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the immunostaining results for eGFP, Glp1r mRNA levels in the isolated islets of 12-week-old βGlp1r;db/db mice were significantly higher than those of control db/db littermates and were restored to similar levels to those in db/m mice at the same age (Fig. 2C).

3.3. Exogenous expression of Glp1r did not affect metabolic profiles in nondiabetic mice but worsened hyperglycemia in db/db mice

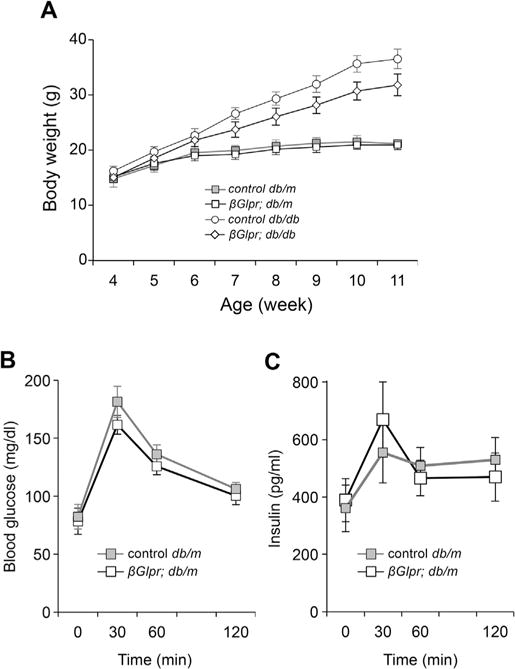

To induce the exogenous expression of Glp1r before the onset of overt hyperglycemia, βGlp1r;db/db mice and their nondiabetic db/m littermates were injected with tamoxifen at the age of four weeks. There was no significant difference in body weight between βGlp1r;db/m and control db/m littermates or between βGlp1r;db/db and control db/db littermates, although the body weights of βGlp1r;db/db mice were slightly lower than those of control db/db mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in βGlp1r;db/m demonstrated no significant difference in blood glucose and plasma insulin levels between βGlp1r;db/m and control db/m littermates (Fig. 3B, C), showing that exogenous Glp1r did not affect glucose profiles in nondiabetic db/m mice.

Fig. 3.

Metabolic profiles in βGlp1r; db/m, βGlp1r; db/db, and their control littermates. (A) Whole body weights were measured every week as indicated. (B, C) Blood glucose levels and insulin levels during OGTT were measured in βGlp1r;db/m mice and control littermates (n = 6 for each group).

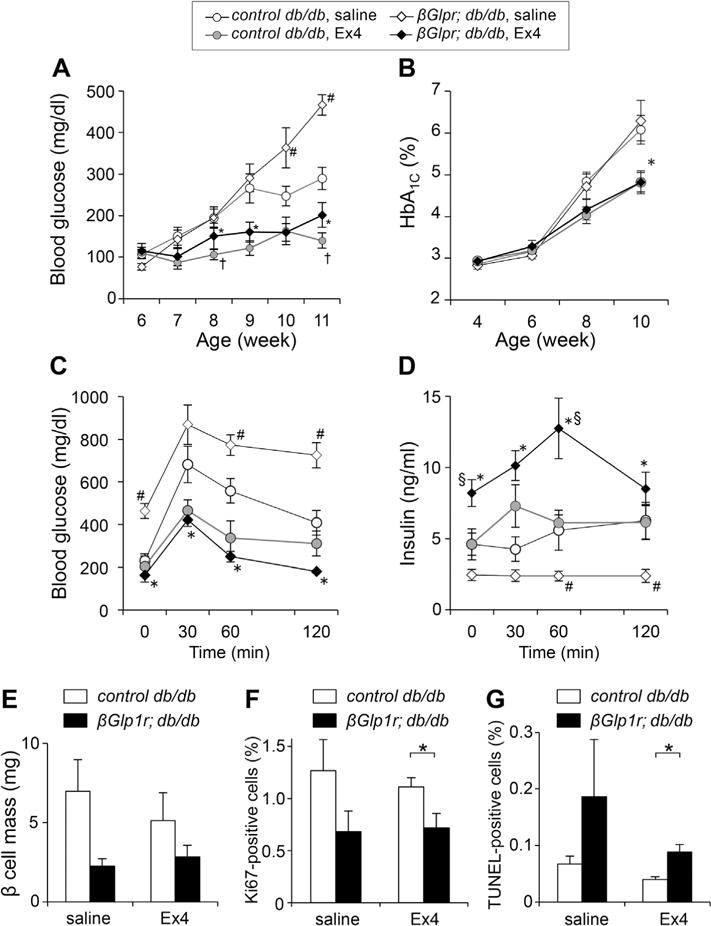

On the other hand, restored expression of Glp1r in diabetic βGlp1r;db/db mice significantly increased fasting blood glucose levels after 10 weeks of age (Fig. 4A), and there were no significant effects on HbA1c levels compared with those of control db/db mice (Fig. 4B). When OGTT was performed on βGlp1r;db/db mice without GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment, blood glucose levels at 2 h after glucose administration were significantly higher in βGlp1r;db/db mice (Fig. 4C), with a significant decrease in plasma insulin levels (Fig. 4D), compared with control db/db littermates. These findings suggest that exogenous Glp1r expression in diabetic db/db mice causes a further impairment in glucose tolerance due to insufficient insulin secretion in response to elevated glucose levels.

Fig. 4.

Metabolic profiles and β-cell function of βGlp1r; db/db mice treated with exendin-4 (Ex4). (A, B) Fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were measured weekly or biweekly in saline-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice (open diamonds, n = 13), saline-treated control db/db mice (open circles, n = 13), Ex4-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice (black diamonds, n = 14), and Ex4-treated control db/db mice (gray circles, n = 13). (C, D) Blood glucose levels and insulin levels during OGTT were measured in βGlp1r;db/db and control littermates (n = 6e8). #, p < 0.05, saline-treated control db/db mice vs. saline-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice; §, p < 0.05, Ex4-treated control db/db mice vs. Ex4-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice; †, p < 0.05, saline-treated control db/db mice vs. Ex4-treated control db/db mice; *, p < 0.05, saline-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice vs. Ex4-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice. (E, F, G) Immunostaining with antibodies against insulin, eGFP, and Ki67 were performed and β-cell mass (E), Ki67-positive cells (F), and TUNEL-positive cells (G) were calculated (*, p < 0.05; n = 4).

3.4. A GLP-1 receptor agonist improves glucose profiles and insulin secretion in Glp1r-overexpressing db/db mice

To investigate whether activation of GLP-1 receptor signaling would improve metabolic profiles in diabetic mice, we treated βGlp1r;db/db mice with the GLP1R agonist exendin-4 at 0.1 mg/kg body weight/day for four weeks using an osmotic pump. Administration of exendin-4 significantly ameliorated both fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels in βGlp1r;db/db mice and control db/db littermates (Fig. 4A, B). In addition, blood glucose and plasma insulin levels during OGTT were significantly improved in exendin-4-treated βGlp1r;db/db mice and control db/db littermates, compared with the mice treated with saline (Fig. 4C, D). In particular, plasma insulin levels in βGlp1r;db/db mice treated with exendin-4 were significantly higher than those in control db/db littermates, suggesting that restored expression of Glp1r efficiently enhanced insulin secretion in response to exendin-4.

3.5. Decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis in β cells of β Glp1r; db/db mice

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of β-cell failure in βGlp1r;db/db mice, histological analyses were performed on their paraffin-embedded tissues of the transgenic mice. When sections immunostained for insulin were assessed for measurement of β-cell area, there was no statistical difference in β-cell mass between βGlp1r;db/db mice and control db/db littermates, although there was a trend toward a smaller β-cell mass in βGlp1r;db/db mice (Fig. 4E). Ki67 staining demonstrated a significant decrease in β-cell proliferation in βGlp1r;db/db mice treated with exendin-4 (Fig. 4F), and the TUNEL assay showed a significant increase in apoptotic β cells in the same mutant mice (Fig. 4G). These findings suggest that restored expression of Glp1r and activation of its signaling in diabetic db/db mice lead to impaired β-cell turnover and apoptosis, although β-cell responsiveness to exedin-4 was enhanced in the transgenic mice.

4. Discussion

Incretin-based therapies, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors, have been widely used for diabetic patients [15]. Although GLP-1 and its analogs have potent effects on stimulating insulin secretion, there is some evidence for the impairment of incretin effect; (1) β-cell responsiveness to GLP-1 was impaired in diabetic patients compared with nondiabetic subjects [16] and (2) GLP-1 analogs are effective in only some diabetic patients, which might be associated with residual β-cell function [6] [7]. In addition, as the mRNA levels of GLP1R/Glp1r were reduced in both human diabetic patients and rodent diabetic models [9] [10] [11] [12], we hypothesized that the decreased expression of Glp1r may affect metabolic profiles by changing the response to endogenous GLP-1 and/or exogenous GLP-1 analogs.

To approach this issue, we used db/db diabetic mice and investigated when and how much the incretin receptors are downregulated during the progression of hyperglycemia. Gene expression analysis at three different ages revealed that the expression levels of Glp1r started to decrease at eight weeks of age, the same time point as a decline in Mafa mRNAs (Fig. 1). As the mRNA levels of Glp1r were comparable at four weeks of age between db/db and db/m mice, the decrease in Glp1r mRNA levels of db/db mice did not precede the development of hyperglycemia. Together with our recent finding that alleviation of glucotoxicity markedly increases Glp1r expression in db/db mice [17], this age-dependent decline of Glp1r mRNAs appears to be a consequence, rather than a cause of hyperglycemia.

We next questioned whether sustained expression of Glp1r might improve the metabolic profiles in db/db mice, and generated a transgenic mouse in which the expression of Glp1r can be induced specifically in β cells only after Cre-mediated recombination following tamoxifen treatment. Contrary to our expectation that sustained expression of Glp1r would have protective effects on β-cell failure in db/db mice, βGlp1r;db/db mice exhibited more profound glucose intolerance compared with control db/db littermates, accompanied by impaired insulin secretion (Fig. 4A–D). As Glp1r mRNA levels in the islets of βGlp1r;db/db mice are similar to those in the islets of nondiabetic db/m mice (Fig. 2C), exogenous Glp1r mRNA was not overexpressed to toxic levels. In other words, sustained expression of Glp1r in β cells under diabetic conditions, even at the physiological levels of Glp1r mRNAs in nondiabetic mice, can lead to β-cell dysfunction. This indicates that the downregulation of Glp1r observed at the age of eight and 12 weeks might be partially protective and required for preventing rapid progression of β-cell failure under diabetic conditions.

It is noted that exogenous Glp1r had no effect on glucose profiles in nondiabetic db/m mice (Fig. 3B, C), which is consistent with a previous report showing that transgenic mice expressing human GLP1R in β cells exhibited normal insulin secretion [18]. Thus, there is a substantial difference in the effect of exogenous Glp1r on diabetic db/db mice and nondiabetic db/m mice, suggesting that the adverse effects of exogenous Glp1r result from β-cell dysfunction, under chronic hyperglycemia and/or leptin signaling deficiency, while insulin secretion in response to a GLP-1 receptor agonist was improved. It would be of interest to treat βGlp1r;db/db mice with antidiabetic agents so that we could improve such adverse effects of transgenic Glp1r and see any beneficial effects of the sustained expression of Glp1r.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Francis Lynn (The University of British Columbia) and Akiko Popiel (Tokyo Medical University) for helpful advice and criticism, and Satomi Takebe for her assistance with the experiments. This work was supported in part by grants from JSPS KAKENHI (No. 25461348), the Takeda Science Foundation, the Suzuken Memorial Foundation (all to TMi), the Lilly Incretin Basic Research Aid Program (to TMi and TMa).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.177.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Halban PA, Polonsky KS, Bowden DW, Hawkins MA, Ling C, Mather KJ, Powers AC, Rhodes CJ, Sussel L, Weir GC. β-Cell failure in type 2 diabetes: postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1751–1758. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyatsuka T. Chronology of endocrine differentiation and beta-cell neogenesis. Endocr J. 2015 doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell JE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013;17:819–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunck MC, Corner A, Eliasson B, Heine RJ, Shaginian RM, Taskinen MR, Smith U, Yki-Jarvinen H, Diamant M. Effects of exenatide on measures of β-cell function after 3 years in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2041–2047. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SN, Johns D, Maggs D, Xu H, Northrup JH, Brodows RG. Exploring the substitution of exenatide for insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin in combination with oral antidiabetes agents. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2767–2772. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozawa J, Inoue K, Iwamoto R, Kurashiki Y, Okauchi Y, Kashine S, Kitamura T, Maeda N, Okita K, Iwahashi H, Funahashi T, Imagawa A, Shimomura I. Liraglutide is effective in type 2 diabetic patients with sustained endogenous insulin-secreting capacity. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:294–297. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song SO, Kim KJ, Lee BW, Kang ES, Cha BS, Lee HC. Tolerability, effectiveness and predictive parameters for the therapeutic usefulness of exenatide in obese, Korean patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5:554–562. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Hill AV, Hyde CJ, Knight BA, Hattersley AT, P.S. Group Markers of β-cell failure predict poor glycemic response to GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015 doi: 10.2337/dc15-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu G, Kaneto H, Laybutt DR, Duvivier-Kali VF, Trivedi N, Suzuma K, King GL, Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Downregulation of GLP-1 and GIP receptor expression by hyperglycemia: possible contribution to impaired incretin effects in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1551–1558. doi: 10.2337/db06-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawashima S, Matsuoka TA, Kaneto H, Tochino Y, Kato K, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto T, Matsuhisa M, Shimomura I. Effect of alogliptin, pioglitazone and glargine on pancreatic β-cells in diabetic db/db mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shu L, Matveyenko AV, Kerr-Conte J, Cho JH, McIntosh CH, Maedler K. Decreased TCF7L2 protein levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus correlate with downregulation of GIP- and GLP-1 receptors and impaired beta-cell function. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2388–2399. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taneera J, Lang S, Sharma A, Fadista J, Zhou Y, Ahlqvist E, Jonsson A, Lyssenko V, Vikman P, Hansson O, Parikh H, Korsgren O, Soni A, Krus U, Zhang E, Jing XJ, Esguerra JL, Wollheim CB, Salehi A, Rosengren A, Renstrom E, Groop L. A systems genetics approach identifies genes and pathways for type 2 diabetes in human islets. Cell Metab. 2012;16:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Fujitani Y, Wright CV, Gannon M. Efficient recombination in pancreatic islets by a tamoxifen-inducible cre-recombinase. Genesis. 2005;42:210–217. doi: 10.1002/gene.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki S, Miyatsuka T, Matsuoka TA, Takahara M, Yamamoto Y, Yasuda T, Kaneto H, Fujitani Y, German MS, Akiyama H, Watada H, Shimomura I. Activation of GLP-1 and gastrin signalling induces in vivo reprogramming of pancreatic exocrine cells into beta cells in mice. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2582–2591. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3728-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368:1696–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjems LL, Holst JJ, Volund A, Madsbad S. The influence of GLP-1 on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: effects on β-cell sensitivity in type 2 and nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2003;52:380–386. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimo N, Matsuoka TA, Miyatsuka T, Takebe S, Tochino Y, Takahara M, Kaneto H, Shimomura I. Short-term selective alleviation of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity ameliorates the suppressed expression of key β-cell factors under diabetic conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamont BJ, Li Y, Kwan E, Brown TJ, Gaisano H, Drucker DJ. Pancreatic GLP-1 receptor activation is sufficient for incretin control of glucose metabolism in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:388–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI42497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.