Abstract

Brief, targeted self-affirmation writing exercises have recently been offered as a way to reduce racial achievement gaps, but evidence about their effects in educational settings is mixed, leaving ambiguity about the likely benefits of these strategies if implemented broadly. A key limitation in interpreting these mixed results is that they come from studies conducted by different research teams with different procedures in different settings; it is therefore impossible to isolate whether different effects are the result of theorized heterogeneity, unidentified moderators, or idiosyncratic features of the different studies. We addressed this limitation by conducting a well-powered replication of self-affirmation in a setting where a previous large-scale field experiment demonstrated significant positive impacts, using the same procedures. We found no evidence of effects in this replication study and estimates were precise enough to reject benefits larger than an effect size of 0.10. These null effects were significantly different from persistent benefits in the prior study in the same setting, and extensive testing revealed that currently theorized moderators of self-affirmation effects could not explain the difference. These results highlight the potential fragility of self-affirmation in educational settings when implemented widely and the need for new theory, measures, and evidence about the necessary conditions for self-affirmation success.

Keywords: values affirmation, replication, stereotype threat, intervention, achievement gap, scale-up, middle school

One potentially promising approach to reducing persistent racial/ethnic achievement gaps is to tackle their social-psychological dimensions, including the negative consequences of stereotype threat and other identity threats in school. Because identity threats have detrimental consequences for marginalized groups in many academic settings (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002), such approaches can have substantial impacts. For instance, brief reflective writing exercises conducted in school settings can provide large and lasting benefits for theoretically-threatened groups, such as African American and Hispanic middle-school students (Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, & Brzustoski, 2009; Sherman et al., 2013), women in a college physics course (Miyake et al., 2010), and first-generation college students (Harackiewicz et al., 2014).

How robust are these effects? Although benefits of seemingly simple interventions suggest great potential, researchers caution that these techniques are “not magic” (Yeager & Walton, 2011). By their nature, the interventions target specific interactions between individuals and their social context and, therefore, critical differences in intervention delivery, individual students, or social contexts may lead to substantial variability in effectiveness. As a result, one must gauge the impact of these interventions in diverse settings and, to the extent that there are meaningful differences in effects, assess whether theorized moderators explain these differences. If heterogeneous effects follow theoretically predictable patterns, then these interventions have a clear role in improving educational outcomes and reducing achievement gaps. However, if heterogeneity remains unpredictable, then the immediate value of these interventions is less clear.

Theorized heterogeneity also complicates the fundamental enterprise of independent replication, which is increasingly recognized as necessary to build firm scientific understanding in psychology as in other fields (Ioannidis, 2005; Ioannidis, 2012; Pashler & Harris, 2012). If the impacts of social-psychological interventions depend on seemingly subtle differences in delivery, individuals, and social contexts, then discrepant replication results may reflect predictable differences in effectiveness across diverse settings. On the other hand, mixed results may be due to unpredictable study-specific differences, such as unrecognized moderators or sampling variation. This distinction is especially difficult to disentangle when studies are conducted by different investigators and with different populations in different contexts. As a result, initial replication efforts of affirmation interventions in educational settings—which demonstrate success (e.g. Sherman et al., 2013), challenges (e.g. Kost-Smith et al., 2012), and failure (e.g. Dee, 2015)—raise questions about both the size and variability of these effects when implemented broadly. In particular, do theorized moderators explain differences in self-affirmation benefits? This study provides unique evidence on this question by reporting on a new large-scale test of self-affirmation effects and comparing these results to a previous effort in the same setting.

Self-affirmation: Theory and Promise

This study is informed by theories of social identity threats, which create particular challenges for members of marginalized social groups in school (Steele et al., 2002). For instance, Black and Hispanic students are subject to stereotype threat in academic settings, in which they face the threat of conforming to or being judged by negative stereotypes about their racial/ethnic group (Steele & Aronson, 1995). The experience of stereotype and other identity threats leads to poorer academic performance through a variety of psychological responses, including stress, anxiety, and vigilance (Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008), and may contribute to longer term disengagement and a “downward spiral” of performance (Cohen & Garcia, 2008). Since these stereotype threats uniquely apply to groups subject to negative academic stereotypes, they may account for portions of the widening of racial achievement gaps in school.

Stereotype threats are pernicious because students are affected by virtue of membership in a marginalized group (regardless of whether or not they endorse a negative stereotype, as long as they are aware of it), and broad social stereotypes are difficult to change. Instead, the goal of many social-psychological interventions is to reduce the harm that existing threats cause by shifting how students view themselves and/or their social world (Wilson, 2011). The example we consider is a set of brief writing exercises that ask students to reflect on meaningful personal values, such as family, friends, music, or sports. Following their initial presentation (e.g. Cohen, Garcia, Apfel, & Master, 2006; Cohen et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2009), we refer to these activities as self-affirmation interventions throughout this paper, reflecting the goal to allow students to “reaffirm their self-integrity” (Cohen et al., 2006, p. 1307). Similar interventions have also been described as “values affirmation” (e.g. Cook, Purdie-Vaughns, Garcia, & Cohen, 2012; Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Shnabel, Purdie-Vaughns, Cook, Garcia, & Cohen, 2013).

Self-affirmation interventions are believed to restore an individual’s sense of worth in the face of threats related to social identity, thus mitigating detrimental stress responses (Steele, 1988). Because individual identities are complex, individuals “can maintain an overall self-perception of worth and integrity by affirming some other aspect of the self, unrelated to their group” (Sherman & Cohen, 2006, p. 206). Threats to academic identity experienced by minority members in school can be muted by focusing attention on other specific aspects of identity (Critcher & Dunning, 2015; Sherman & Cohen, 2006; Steele, 1988; Walton, Paunesku, & Dweck, 2012). Reflection on important values provides a psychological buffer against the full brunt of detrimental stereotype threats in school, and because of the potentially recursive nature of threat and poor performance, subtle buffering early on may lead to substantial benefits over time (Cohen & Garcia, 2008; Cohen et al., 2009; Taylor & Walton, 2011; Walton, 2014).

Geoffrey Cohen and his colleagues have developed these theoretical ideas alongside specific classroom writing activities to promote self-affirmation via reflection on important values. Each activity takes 15–20 minutes and is conducted by classroom teachers several times during the school year; the timing emphasizes critical moments such as the beginning of the school year and potentially stressful evaluative milestones. Consistent with theoretical expectations, these activities did not significantly impact White students’ academic performance, who likely experienced relatively little academic identity threat (Walton & Cohen, 2003). However, the effects on grade point average for 7th grade African American and Hispanic students were substantial and persistent (Cohen et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Sherman et al., 2013). Remarkably, the benefits of the intervention reduced the racial achievement gap in the targeted course by 40% (Cohen et al., 2006, p. 1307), which suggests great potential for this approach to address educational disparities that are associated with identity threat processes.

What mediates these effects? Critcher and Dunning (2015) presented recent laboratory evidence for an “affirmation as perspective” model, in which self-affirmations “expand the contents of the working concept—thus narrowing the scope of any threat” (p. 4). Working concept refers to the salient identities that make up one’s self-concept in consciousness at any point in time. When aspects of identity are threatened, working self-concept tends to constrict, amplifying the negative experiences of that threat. However, if a broader working concept is maintained, then threats associated with a specific aspect of identity are less salient. It stands to reason that self-affirmation in school expands the contents of self-concept for students subject to academic stereotypes, thus reducing attention to the threat and muting the stress responses that lead to poorer performance.

Empirical tests of mediators in middle school settings have been mixed. Cook et al. (2012) reported impacts of self-affirmation on Black students’ level and variability of sense of belonging in school, which indicate effects on students’ construal of their social environments, but the authors argued that these effects are “not a mechanism in the sense of mediation” (p. 483). Similarly, Sherman et al. (2013) reported impacts on higher levels of construal and a more robust sense of social belonging, while Cohen et al. (2006) reported decreases on a measure of cognitive activation of racial stereotype, yet neither found evidence that these effects mediated the impact of self-affirmation. Shnabel et al. (2013) found that writing about social belonging mediated some of the self-affirmation benefits; however, Tibbetts et al. (in press) did not replicate this result in another setting and instead found that writing about independence mediated some of the affirmation benefits.

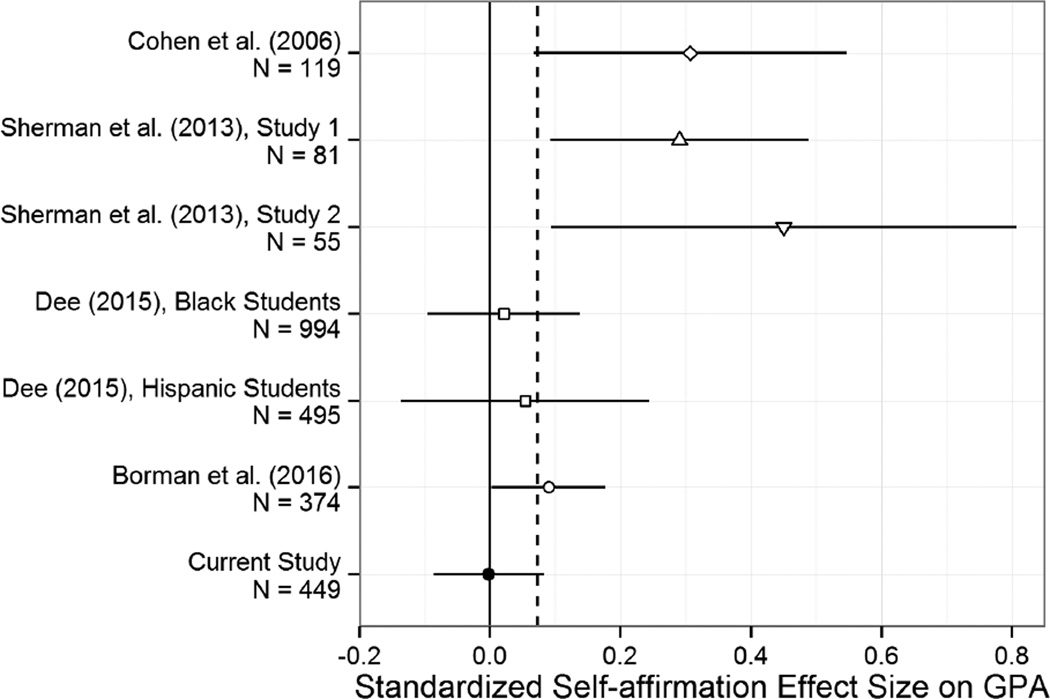

The self-affirmation writing exercises have been implemented in at least four middle school field settings beyond the original one. Figure 1 summarizes both the positive impacts from early field trials within three schools (Cohen et al., 2006; Sherman et al., 2013) and smaller and sometimes non-statistically significant estimates in large-scale, multi-school replications (Borman, Grigg, & Hanselman, 2016; Dee, 2015).1 The latter are well-powered studies conducted by independent research teams, and their results raise questions about the fundamental sources of variability in self-affirmation effects. Unfortunately, many features of the research settings varied in these studies and little implementation information is available to isolate the impact of specific differences. For instance, the study conducted by Dee (2015) illustrates multiple potentially relevant changes across research efforts. For one, it was conducted in schools with substantial minority student populations; these are contexts where self-affirmation may be less effective (Hanselman, Bruch, Gamoran, & Borman, 2014). For another, it recruited an unusually representative sample of students (a 94% consent rate), which could account for dampened impacts if the students not typically included in other studies benefit less from the intervention. These preliminary results suggest the need for more precise consideration of where, for whom, and under what conditions self-affirmation is beneficial.

Figure 1. Estimated Effects of Self-affirmation Writing Exercises on Middle School Grade Point Average.

Source: Authors’ calculations; see Table A1 for specific references.

Notes: Symbols plot reported effect sizes for potentially stereotyped groups (African American and/or Hispanic students) for the first year of the self-affirmation intervention, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals (+/− 1.96 standard errors). Shapes represent distinct school or district contexts. For instance, Sherman et al. (2013) studies 1 and 2 were conducted in different schools in different states. Dee (2015) reports subgroup results from the same sample of Philadelphia-area schools. The dashed line represents the overall mean effect size (0.07), calculated by weighting individual estimates according to the inverse of their squared standard error. The impact estimates are lower in the large-scale replication studies (Dee 2015, Borman et al. 2016, and Current Study), but these differences could reflect heterogeneous effects across local context, research team, and implementation. This paper investigates two effects observed within the trial conducted in a single school district (represented by circles), for which context and procedures were consistent.

Theoretical Moderators of Self-Affirmation Effects

Psychological theory posits that self-affirmation is beneficial in specific circumstances (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Yeager & Walton, 2011), highlighting the need to identify the necessary and sufficient “preconditions” for its benefits in educational settings (Cohen et al., 2006). Null results emphasize this point, since existing theory provides post hoc explanations but not clear insight into when, where, and why self-affirmation might not have worked (e.g., see Harackiewicz, Canning, Tibbetts, Priniski, & Hyde, in press). And of course if moderators were well understood, then studies would likely not have been fielded in such unsuccessful contexts.

In surveying potential self-affirmation moderators, the literature points to three relevant domains: features of the delivery of the activities, individual characteristics of the participating students, and aspects of the social context. First, specific features of the delivery of the brief self-affirmation intervention are hypothesized to be necessary for students to benefit. For example, Critcher, Dunning, and Armor (2010) found that self-affirmation exercises were only effective when introduced before a threat or before participants became defensive in response to a threat, which suggests that it is important to implement self-affirmation exercises before stressful events in school in order to short-circuit negative recursive cycles (see also Cohen & Garcia, 2014; Cook et al., 2012). Qualities of presentation that shape how students perceive the writing activities—such as making participants aware that exercises are beneficial (Sherman et al., 2009) or externally imposing affirmation (Silverman, Logel, & Cohen, 2013)—may mute self-affirmation benefits. Conversely, researchers have argued that the activity is most beneficial when presented as a normal classroom activity (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2009) and when promoting specific types of writing (e.g., Shnabel et al., 2013). Finally, the type of control group used has also been suggested as an implementation-based moderator of the effects of self-affirmation. The typical control group, which asks students to write about non-important values, has the potential to undermine students’ confidence if they write about activities in which they have low ability whereas other control writing prompts, which are more neutral or open-ended, might allow control participants to spontaneously affirm themselves (McQueen & Klein, 2006).

Second, numerous individual difference variables have been hypothesized to make students more vulnerable to stereotype threat and thus moderate the effects of self-affirmation, including identifying with a negatively stereotyped group, being knowledgeable about self-relevant negative stereotypes, and caring about doing well in school (Aronson, Lustina, Good, Keough, & Steele, 1999; Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Shapiro & Neuberg, 2007). Therefore, while all negatively stereotyped minority students might be helped by self-affirmation, subgroups that are even more highly negatively stereotyped, such as Black males (Eagly & Kite, 1987; Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) or the lowest-achieving minority students (Cohen et al., 2009), might benefit most from self-affirmation.

Finally, context variables are hypothesized to moderate self-affirmation benefits. Social characteristics, such as group composition and environmental cues, influence the behavior and performance of stereotyped students (Dasgupta, Scircle, & Hunsinger, 2015; Inzlicht & Ben-Zeev, 2000; Murphy, Steele, & Gross, 2007). The effectiveness of self-affirmation approaches depends on the identity threats “in the air” in a particular setting (Steele, 1997), and the hypothesized recursive benefits are theorized to depend on relatively rich learning environments for threatened students to take advantage of as they are buffered from perceived threats (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). Because self-affirmation is theorized to disrupt stereotype threat processes, settings in which threats are more likely to be experienced may provide the greatest opportunity for benefits. For instance, while self-affirmation reduced gender disparities in performance in an introductory college physics course (Miyake et al., 2010), it was not beneficial in introductory science settings in which gender gaps and stereotype threat were not present (Lauer et al., 2013). Theory and empirical evidence also suggest that minority students attending schools in which their group is poorly represented and in which there are large racial achievement gaps benefit most from self-affirmation (Cohen & Garcia, 2014; Hanselman et al., 2014).

In summary, psychological theory posits moderators of self-affirmation effects in several domains, but evidence for specific moderators is limited because the data to test these theories are lacking, especially in applied educational settings. This means that mixed evidence of self-affirmation benefits may be due to theorized variation in how the activities were delivered, individual characteristics, or social contexts. In particular, very little is known about how to translate theorized constructs and laboratory manipulations into measures of the relevant moderating features as they occur in applied settings. Moreover, it is impossible to isolate specific relevant differences between the independent field trials to date, which have been conducted in different contexts with different populations and different procedures. Nonetheless, interrogating potential moderators is key to assessing both the underlying theory of self-affirmation and its likely practical impact. To the extent that a priori hypotheses predict heterogeneity, these results would confirm theory and point to where these strategies have the most potential to improve student outcomes. On the other hand, it is possible that mixed self-affirmation results are not explained by currently theorized moderators, which would imply the need for greater and more specific inquiry into the necessary conditions for success.

A New Self-affirmation Replication Study

Given variable evidence of impacts in applied settings, we tested the effects of brief, in-class self-affirmation writing exercises for 7th grade students on subsequent academic outcomes in a new double-blind randomized experiment in a sample of over 1200 students in one Midwestern school district. We sought to learn whether similar benefits could be attained in a different setting, both in terms of geographic location and scale of implementation.

The Original Study

The original self-affirmation study in a middle school setting was first reported by Cohen et al. (2006), with supplemental analyses elsewhere (Cohen et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Shnabel et al., 2013). We replicated the procedures in the original experiments as described below. Cohen and his colleagues originally reported several substantively important features of self-affirmation intervention on student outcomes: substantial persistent benefits for “negatively stereotyped” students (African American and Hispanic students) on Grade Point Average; significantly higher benefits for low-performing African American students; an improved trend in grades throughout the year; and no benefits for European American students. Our primary focus was on the first finding, representing the highly policy-relevant main impact of the intervention on negatively stereotyped groups. The impact for African American students ranged from 0.21 to 0.34 GPA points across individual experiments and across courses (Cohen et al., 2006, p. 1308).

The Previous Independent Replication in the Current Research Setting

The immediate precedent for the current self-affirmation replication is the study reported by Borman et al. (2016). That study was the first successful independent replication of the benefits of self-affirmation benefits in middle schools. The researchers reported statistically significant benefits for “potentially threatened” students (Black and Hispanic) on 7th grade GPA across all schools in the district. Like the original study, term-specific GPA data revealed a less negative trend for potentially threatened students in the self-affirmation condition, and no benefits for “not potentially threatened” students (White and Asian). Some results deviated from the original patterns. For one, the impacts were smaller, with an impact of 0.065 cumulative GPA points; the confidence interval for this estimate was (0.001, 0.128), which excludes all impact estimates from the original study. The authors speculated that this difference may have been at least partially related to the challenges of implementing at scale. Also, the replication found no evidence of an interaction between the intervention and prior achievement. In supplemental analyses, researchers reported that the treatment benefits in this scale-up were concentrated in a subset of schools hypothesized to have the most threatening environments for potentially threatened groups, based on the numerical presence and relative academic standing of these students (Hanselman et al., 2014).

The Current Study

The current study was designed to replicate both the original self-affirmation study (Cohen et al., 2006) and the previous successful independent replication (Borman et al., 2016). Three key features of this design provide unique insights into the effects of self-affirmation in educational settings. First, procedures followed those in the original study, including intervention materials, as we detail below. The study therefore is an example of a well-powered “close” replication of the effects of self-affirmation for potentially threatened groups in middle school (Brandt et al., 2014). Moreover, given the scale of the research, the study contributes important evidence about the general promise of these interventions to improve minority students’ achievement.

The second key feature of the study is that it was conducted in the same setting as a previous randomized trial of self-affirmation, in the same district and schools, by the same research team, with the same research protocols. In the current study, we ask whether these middle school scale-up results were replicated, and we use comparisons across studies to test theorized sources of heterogeneity. Since features of the study corresponded closely to those in the previous one (Borman et al., 2016; see Table A2 for a summary), the within-setting comparisons across the two studies allow for much more specific tests of moderation than comparisons between settings. A recent precedent for such a within-setting comparison is provided by Harackiewicz et al. (in press), who found different affirmation effects in a college setting and discussed several potential explanations for the difference. We exploit a similar pattern to conduct comprehensive tests of theorized sources of heterogeneity.

A third contribution of this study is that we collected information on self-affirmation implementation, including qualitative features of students’ responses to the exercises. These data provide an unprecedented picture of the experience of the self-affirmation activities when they are implemented in an entire school district. And, in combination with information about individual student characteristics and features of the social context, this information supports unique tests of the theorized sources of heterogeneity.

Building on the unique empirical features of this research, we addressed three sequential research questions. Our first question was: (1) what was the effect of the self-affirmation intervention in the new large-scale implementation? Because we found no evidence of benefits, we asked: (2) were estimated effects substantively and significantly different from the impacts for the students from a previous study in the same setting? Given meaningful and detectable differences, we finally asked: (3) why was the same intervention seemingly beneficial for targeted students in one implementation but less so in the next?

The third research question is the most theoretically important, but it also is the most challenging. To preview our approach, we drew on the theory underlying the design of the interventions to conduct a series of tests of potential explanations for differences in effects across studies. Based on hypothesized moderators of the impacts of self-affirmation, these explanations fall into three broad classes: characteristics of implementation, individuals, and social context. We then conducted a series of empirical tests of these potential explanations to assess which, if any, explained the differences in experimental impact estimates.

Method

The Large-scale Self-Affirmation Studies

All data were generated or collected as part of two randomized trials of self-affirmation writing activities among 7th grade students. The research was conducted through a partnership with the school district, which recognized large racial achievement gaps and was interested in strategies to improve the performance of minority students. District administrators provided support to the project, and principals at all 11 regular middle schools agreed to participate. Given this support, study implementation involved researchers (who provided training and activity materials), school learning coordinators (who coordinated the site-specific logistics, including scheduling), and teachers (who implemented the activities in their classrooms). The involvement of educators in diverse roles approximated how the exercises would be likely to be implemented if adopted as a universal district initiative.

Throughout this paper we refer to the first study, conducted with 7th grade students in 2011–2012, as “cohort 1” and the second study, conducted in 2012–2013, as “cohort 2.” The focus of this paper is on the new evidence on self-affirmation effects provided by cohort 2; no results from this study have been reported previously. In order to compare results across the two studies, we also conducted new analyses of participants in cohort 1, including documenting impacts in 8th grade. We therefore detail aspects of both the new study (cohort 2) and the previous one (cohort 1).

The general outline of both studies was similar, as follows: Research activities began in the summer with parallel contact at each of district’s 11 middle schools. After confirming authorization from the principal and identifying an appropriate setting for the writing exercises with each school’s learning coordinator, research staff provided a training session for the 7th grade instructional teams at each school. During the 30-minute training session, a member of the research staff introduced the study as research about 7th grade students’ experiences, beliefs, and social-emotional learning. The researcher described the mechanics of implementation and reviewed the teacher implementation script. Teachers administered the writing exercises during normal class time with materials provided by the research team and the completed exercises were returned to the research team for recording. After the school year, the district provided administrative data, including transcript and demographic information. No study activities were conducted after the 7th grade year, but additional administrative data on 8th grade performance were collected after the following year.

Below we highlight the core features of the intervention, with a focus on similarities and differences between the two studies. Appendix Table A2 provides a summary.

Self-affirmation Intervention and Implementation

The self-affirmation intervention procedure followed Cohen et al. (2006). Seventh grade students completed a short (15–20 minute) writing prompt as part of normal class activities several times during the school year. We identified four time points for the self-affirmation writing interventions. These provided a consistent template for the district, but scheduling varied according the formative assessment dates in individual schools. The time points were: (1) at the start of the school year, in the week prior to formative fall standardized assessments, (2) in November, in the week prior to the state’s standardized achievement test for accountability purposes, (3) in the winter, in the week prior to a midyear language skills formative assessment, and (4) in the spring, in the week prior to the final formative assessment of the year. Based on the evidence that self-affirmation exercises are most effective earliest in the school year (Cook et al., 2012), we provided school officials with the option of omitting the winter exercise to reduce logistical challenges; four schools did so for cohort 1 and two did so for cohort 2.

The activities were administered by teachers in the classroom using scripts provided by the original research team. 45 teachers were involved in cohort 1, 44 were involved in cohort 2, and 33 were consistent across both studies; teacher changes reflected exits from the school, re-assignments, and looping (teachers moving grades along with students). The intervention activities were completed in a classroom setting determined by the school’s learning coordinator to be the most appropriate for the writing exercises: in Language Arts classes at seven schools and homeroom period at four (constant across both cohorts). Homeroom periods were abbreviated classes with non-academic curricula, including activities related to socio-emotional standards. In either case, exercises were implemented among all 7th graders in these regular classrooms by their classroom teachers.

The activities were packets of 3–4 pages with prompts and spaces for individual writing responses. They were identical on the cover sheet, which included the student’s name. On subsequent pages the exercises varied by randomly assigned condition (for consented students; all non-consented students, including newly enrolled students without a personalized packet, completed the procedural/neutral control prompts). The treatment condition, following the original study, prompted students to reflect on values (such as friends, family, music, or sports) that were important to them. The precise format of the treatment exercise varied throughout the year to avoid repetition. There were two randomly assigned control conditions: one focused on values, in which students are asked to select least important values from the same list presented to treatment students and explain why they may be important to someone else, and a second devoted to various procedural writing prompts, such as describing summer activities or explaining how to open a locker (we refer to these prompts as “neutral,” as they do not explicitly concern values). The latter control branch was introduced after the first administration in the cohort 1 study, so all control students in the first cohort received the “Least Important Values” prompt for the first exercise. Because we found no evidence of differences between control conditions in either cohort nor evidence that these differences explain differential impacts, we combined both control groups in our main analyses.

Individualized packets were prepared for every student in the district based on classroom rosters and distributed to teachers ahead of implementation. The priority in implementation procedures was to promote an environment in which students engaged in the genuine self-reflection about aspects of identity that is hypothesized to lead to self-affirmation benefits. One implication, following previous research, is that activities were to be conducted as a normal part of classroom activity; this point was stressed in the teacher training and implementation scripts. However, the fact that teachers implemented the activities independently in their own classrooms created challenges for documenting precise features of implementation, as we discuss below.

We also instructed teachers to avoid representing the activities as evaluative, to avoid reference to external research, and to avoid presenting the activities as beneficial. These guidelines were based on theory and empirical evidence (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Silverman et al., 2013), with the caveat that there is little existing guidance about how these features translate into best practice for teachers in established educational settings. For instance, anecdotal feedback from teachers highlighted some tension between these theoretical ideals and integration into classroom activities. For many students and some teachers, the medium of the activities—a personalized packet completed individually—led to a default perception of the activities as a test or assessment. We made efforts to mitigate these perceptions. For instance, previous studies have distributed activities in individual envelopes. In initial planning, we found this to be well outside the norm of classroom activities in the current setting, and instead used a collated packet of papers with a cover sheet to mask differences across conditions.

Some teachers also reported questions from students along the lines of: “if this isn’t graded, why do I have to do it?” One response was for teachers to justify the activities as part of a research study. Recognizing the potential for such deviations from instructions, researchers never described the project to teachers in terms of stereotypes, identity, or self-affirmation. Instead, researchers emphasized that the study concerned the thoughts and opinions of middle school students. Therefore, to the extent that teachers presented or justified the activities as part of a research project, they communicated that students’ responses were valued, which we expected would encourage expressive self-reflection.

Comparison to Original Study

In the context of replication, it is important to be clear about key similarities and differences in protocol, subjects, and context. This is particularly true for interventions in applied school settings, where procedures must be sensitive to local conditions and can shift over time due to logistical constraints or contextual appropriateness. Previous self-affirmation interventions highlight this point: Sherman et al. (2013) reported creating simplified versions in a setting with many English Language Learners, and even in the original setting, the experimental protocols (including the number of exercises, and instructions for choosing important values) shifted between years (Cohen et al., 2006).

The current study set out to replicate the original research (i.e., Cohen et al., 2006) as closely as possible at a larger scale in a new setting. Intervention materials—student exercises and teacher implementation instructions—were provided by the original research team. The fielded activities correspond most closely to Experiment 2 reported by Cohen et al. (2006)—circling important values instead of marking most and least important—and the simplified version employed by Sherman et al. (2013). Timing followed the original experiments, prioritizing a first administration as early in the school year as possible and spacing additional implementations throughout potentially stressful periods later in the school year.

The original study included three to five 7th grade implementations, depending on experiment (Cohen et al., 2009); we fielded three or four (depending on school) in both cohorts. In contrast to the original studies, we did not field implementations in 8th grade; a maximum of four implementations was feasible in the current context, and we prioritized the earliest activities. The original study also administered a student survey at the beginning and end of the 7th grade academic year. The survey addressed students’ “self-perceived ability to fit in and succeed in school” (Cohen et al., 2009, p. 401). We conducted a similar survey at the beginning and end of the 7th grade school year for cohort 2. In this respect, the cohort 2 study was more similar to the original research than cohort 1, when no surveys were administered.

The original study was conducted in a single school, described as “middle- to lower-middle-class families at a suburban northeastern middle school whose student body was divided almost evenly between African Americans and European Americans” (Cohen et al., 2006, p. 1307). The current context included students in 11 Midwestern middle schools in a single district. Overall student 7th grade enrollments in the district were 45% White, 25% Black, 19% Hispanic, and 10% Asian. Based on the original finding that results were consistent when non-Asian minority students were combined as “potentially stereotyped,” we combined Black and Hispanic (including multiracial) students in preferred analyses. Across the 11 schools, the share of potentially threatened students ranged from 19% to 81%. As in the original study, the intervention was provided to students independently by teachers in their classrooms, with materials provided by the research team. The original study was conducted with 3 teachers. The current study (cohort 2) was conducted with 44 teachers in 77 classrooms.

Our analyses include only administrative outcomes. It was not feasible to collect the more detailed outcome measures of the original study, including teacher gradebooks and a race activation task at the end of grade 8 (Experiment 2) or grade 7 (Experiment 1). However, we collected state standardized achievement test results, which were not considered in the original research.

Fidelity

Previous research provides little specific guidance on how to identify or measure the most relevant aspects of self-affirmation implementation, but the anecdotal challenges that teachers reported in implementing the activities in their classrooms highlight the need for more attention to these issues in applied settings. We considered several indicators of fidelity. One indicator is whether students responded to the writing prompts. By that standard, fidelity was quite high in both cohort 1 and cohort 2. In terms of basic exposure to the assigned materials, 88–95% of students completed the assigned activity for each administration. Student absences from class accounted for the majority of non-completion, while less than 1% of students in each administration completed a non-assigned packet due to administrative errors (such as a roster change).

We also coded the content of all students’ responses, distinguishing between responses that showed clear evidence of self-affirming reflection and those that did not. Each response was coded independently by two trained coders who were blind to the experimental condition. A response was coded as self-affirming if it met three criteria: (1) the student wrote about themselves, (2) the response identified a listed “value” from the experimental prompt, and (3) the text expressed either the importance of the value (for example: “My family is the most important thing to me because…”) or that they are “good in” the valued domain (example: “I’m good at drawing.”). Inter-rater agreement was above 80% in both cohorts, and discrepant cases were resolved with the guidance of a core research team member. Based on those measures, fidelity to treatment was high in both cohorts, with 98.0% of treatment students providing at least one response reflecting self-affirming reflection, and 95.8% doing so during the first two exercises of the year.

Although our study is unprecedented in the scale at which we have documented fidelity in self-affirmation writing exercises, we acknowledge that it is possible for more subtle aspects of implementation to have failed in ways that we could or did not observe. Teachers’ independent actions in the classroom, as discussed above, provide one example. Educational research has highlighted the organizational mechanisms that buffer teachers’ practice from external demands (Weick, 1976) and the role of individual teachers’ sense-making in shaping how reforms are enacted in the classroom (Coburn, 2004). We therefore gathered additional evidence with a teacher survey conducted at the end of each school year. These responses should be interpreted with caution for several reasons: we obtained reports from the teachers of only 56.0% of students (46.1% for cohort 1 and 64.2% for cohort 2), the items were retrospective reports (6 months on average after the fact), and it is unknown whether these (or any) teacher behaviors are critical to self-affirmation success. Nevertheless, these data complement other implementation measures and provide a preliminary window into teachers’ administration of the activities.

Teacher responses supported the anecdotal reports discussed above, suggesting that the presentation of the exercises was not always as directed. Teachers of 31.1% of students reported describing the writing exercises as being part of a research study, and teachers of 20.3% of students reported describing the activities as “good for” students. These deviations may have detracted from the effectiveness of the self-affirmation activities, but we do not know how they compare to previous studies, since prior research has not reported systematically on teacher administration.

Sample

Because the study was administered in regular classrooms, all students in these classrooms completed some form of individual activity during implementation. However, students were only participants in the study (i.e., they were randomized to experimental condition, had data collected, and were included in analyses) if they assented and their parents consented. All seventh grade students in all 11 regular middle schools in the Midwestern school district were recruited to participate at school registration days (attended by the vast majority of parents and students) at the end of summer and with follow-up at the start of the school year. In the cohort 1 study, we received consent and assent for 63.6% (1048/1648) of the population; for cohort 2 the number was 72.8% (1269/1722), reflecting improved recruiting efforts. Study participants were individually randomly assigned to the experimental group with randomization blocked by school.

Because attrition was low, even into 8th grade, we analyzed a consistent full cases sample. We dropped 9.0% of cases overall due to missing data/attrition: 2.6% of cases were missing data on covariates we included in models for precision, an additional 4.4% had no transcript data in 8th grade, and 2.1% more were missing standardized testing outcomes. The extent of attrition overall and the individual sources of attrition were statistically equivalent across experimental condition (cohort 1: 10.6% treatment and 10.2% control, χ2=0.03, df=1, p=0.86; cohort 2: 7.5% and 8.1% attrition, respectively, χ2=0.14, df=1, p=0.71); overall attrition was higher for cohort 1 than cohort 2 (10.4% vs. 7.8%, χ2=4.75, df=1, p=0.03). To the extent that differential attrition contributed to possible differences between cohorts, it would have operated (along with differences in recruiting) through different types of individuals being included in the two analytic samples, which we addressed explicitly (see “Individual Student Differences” Results section).

Measures

All student demographic information was derived from district administrative records. Our primary individual demographic variable was an indicator for students’ potential susceptibility to social identity threats relating to academic performance in school, which we operationalized as African American or Hispanic racial/ethnic group membership. We treated multiracial students as potentially susceptible to racial identity threat because they are likely to identify with or be perceived as a member of a marginalized group, but results were similar when these students were excluded (see Figure 3, Panel C). To the extent that administrative racial/ethnic group membership misrepresents susceptibility to social identity threats, our impact estimates may have been attenuated, but similarly so for both cohorts.

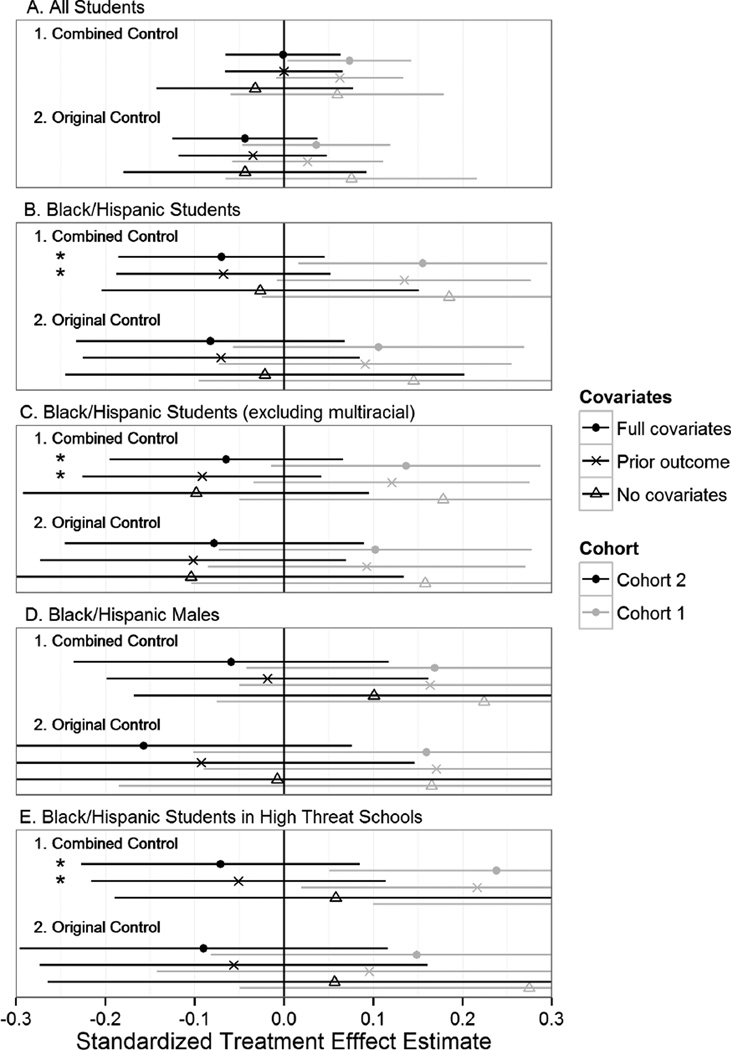

Figure 3. Estimated Self-affirmation Treatment Effects on Grade 8 GPA by Cohort, Sample, Comparison Group, and Included Covariates.

GPA = Overall Grade Point Average; CI = Confidence Interval

Note: Each estimate was calculated from a separate multilevel model (students nested within schools) of intention to treat effect of the self-affirmation writing activities. Full covariates specifications include: grade 6 GPA, gender, special education status, Limited English Proficiency designation, and eligibility for free or reduced price lunch. Prior outcome is grade 6 GPA. In the “Original Control” condition, students wrote about a least important value in each of the first two interventions. The “Combined Control” group includes these students as well as those who were assigned at least one writing prompt that did not explicitly mention values. For readability, the displayed range is restricted to effect sizes of absolute value 0.3 or less. Asterisks indicate that the estimated effects are statistically significantly different between cohorts (p < 0.05), based on a pooled model. The primary result, reported in Table 2, is the estimate for Black/Hispanic sample with combined control condition and full covariates (Panel B1 circles). Other results assess whether patterns were different for subpopulations and comparisons where self-affirmation benefits are hypothesized to be stronger and more consistent, as described in the text. Because the cohort difference persists across all specifications (although less precise in smaller subsamples), these tests provide no evidence that hypothesized moderators explain the difference.

To increase the precision of the self-affirmation treatment effect estimates, we included additional baseline student characteristics in our preferred specification for impact models. These included pre-treatment (grade 6) achievement outcomes and binary indicators for female, limited English proficiency status, receipt of special education services, and eligibility for free or reduced price lunch, which we included as a proxy for family economic resources. Results were substantively similar when we excluded these covariates (see Figure 3 and Appendix Figure A1).

In some models, we restricted the sample to schools with relatively low proportions of Black and Hispanic students and relatively large prior achievement gaps for those students, both of which serve as proxies for more potentially threatening school contexts. Following previous research, we created a binary indicator for potentially threatening school contexts, defined as schools with below average numbers of Black and Hispanic students and above average prior racial achievement gaps (Hanselman et al., 2014).

Our ultimate interest was students’ academic performance. The primary outcomes, following previous research in the self-affirmation literature, were students’ overall grade point average (GPA) in grade 7 and grade 8. GPA reflects overall academic performance across all academic subjects and was recorded on a 4-point scale. Results were robust to focusing on only core academic courses, which corresponded closely to overall GPA (correlations of 0.98–0.99 in each grade). We gave grade 8 GPA conceptual priority, as it was the only grade point average measured entirely subsequent to the full treatment regime.

In supplementary analyses, we assessed treatment effects on a standardized academic assessment, the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE) tests in mathematics and reading. During the study period, WKCE tests were administered for state accountability purposes in November of grade 7 and grade 8. Although the grade 7 tests were administered relatively early in the course of the intervention, the second exercise explicitly targeted the potentially high stress week prior to WKCE testing, making effects on this early outcome worthy of consideration.

Experimental Balance

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics and tests of baseline experimental equivalence for each cohort, both overall and within the subset of potentially threatened (Black and Hispanic) students. The sample was majority White, but included a substantial number of potentially threatened students in each cohort (reported numbers include multi-racial students). Pre-treatment differences between the treatment and control group were substantively small (generally less than 0.1 standard deviations) and not statistically significantly different, suggesting that randomization was successful in yielding comparable groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Experimental Balance by Study, Overall and for Potentially Threatened Students (Black/Hispanic)

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Variable |

Mean | C Mean |

T Mean |

Std Diff. (C-T) |

p | Mean | C Mean |

T Mean |

Std Diff. (C-T) |

p |

| All Students | [939] | [465] | [474] | [1170] | [580] | [590] | ||||

| Female | 0.502 | 0.520 | 0.483 | 0.075 | 0.253 | 0.499 | 0.498 | 0.500 | −0.003 | 0.953 |

| Potentially Threatened | 0.353 | 0.357 | 0.348 | 0.019 | 0.776 | 0.384 | 0.367 | 0.400 | −0.067 | 0.250 |

| American Indian | 0.039 | 0.047 | 0.032 | 0.080 | 0.218 | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.036 | −0.046 | 0.434 |

| Asian | 0.106 | 0.092 | 0.120 | −0.090 | 0.168 | 0.142 | 0.147 | 0.137 | 0.027 | 0.650 |

| Black | 0.183 | 0.163 | 0.203 | −0.101 | 0.122 | 0.230 | 0.209 | 0.251 | −0.100 | 0.086 |

| White | 0.757 | 0.768 | 0.747 | 0.049 | 0.456 | 0.702 | 0.712 | 0.692 | 0.045 | 0.443 |

| Limited English Proficiency | 0.144 | 0.159 | 0.129 | 0.087 | 0.184 | 0.170 | 0.167 | 0.173 | −0.015 | 0.798 |

| Free/Reduced Lunch | 0.411 | 0.413 | 0.409 | 0.007 | 0.910 | 0.463 | 0.459 | 0.468 | −0.018 | 0.753 |

| Grade 6 GPA | 3.27 (0.64) |

3.28 (0.65) |

3.27 (0.63) |

0.009 | 0.896 | 3.19 (0.67) |

3.21 (0.68) |

3.18 (0.67) |

0.042 | 0.477 |

| Grade 6 WKCE Math | 525.3 (57.5) |

522.2 (57.8) |

528.4 (57.1) |

−0.108 | 0.098 | 516.8 (51.7) |

515.0 (51.1) |

518.6 (52.3) |

−0.071 | 0.227 |

| Grade 6 WKCE Reading | 510.8 (56.4) |

508.0 (56.7) |

513.6 (56.0) |

−0.100 | 0.127 | 504.8 (57.1) |

505.0 (57.4) |

504.5 (56.9) |

0.009 | 0.872 |

| Black/Hispanic Students | [331] | [166] | [165] | [449] | [213] | [236] | ||||

| Female | 0.489 | 0.512 | 0.467 | 0.091 | 0.410 | 0.566 | 0.568 | 0.564 | 0.009 | 0.923 |

| Potentially Threatened | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| American Indian | 0.112 | 0.133 | 0.091 | 0.132 | 0.231 | 0.082 | 0.075 | 0.089 | −0.050 | 0.595 |

| Asian | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.064 | 0.560 | 0.020 | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.110 | 0.244 |

| Black | 0.520 | 0.458 | 0.582 | −0.248 | 0.024 | 0.599 | 0.568 | 0.627 | −0.120 | 0.203 |

| White | 0.568 | 0.584 | 0.552 | 0.066 | 0.548 | 0.519 | 0.521 | 0.517 | 0.008 | 0.930 |

| Limited English Proficiency | 0.293 | 0.343 | 0.242 | 0.221 | 0.044 | 0.294 | 0.300 | 0.288 | 0.027 | 0.775 |

| Free/Reduced Lunch | 0.801 | 0.819 | 0.782 | 0.094 | 0.395 | 0.851 | 0.864 | 0.839 | 0.070 | 0.461 |

| Grade 6 GPA | 2.85 (0.65) |

2.83 (2.83) |

2.87 (0.61) |

−0.061 | 0.583 | 2.78 (0.65) |

2.75 (0.63) |

2.80 (0.66) |

−0.076 | 0.420 |

| Grade 6 WKCE Math | 491.3 (53.1) |

488.9 (55.2) |

493.8 (51.1) |

−0.092 | 0.406 | 486.1 (44.7) |

482.6 (44.7) |

489.3 (44.6) |

−0.149 | 0.114 |

| Grade 6 WKCE Reading | 477.9 (53.3) |

475.9 (51.9) |

480.0 (54.8) |

−0.076 | 0.490 | 471.9 (52.1) |

471.3 (52.5) |

472.4 (51.9) |

−0.021 | 0.823 |

T = Treatment, C = Control, Std Diff. = Treatment-control in standardized units, p = p-value for test of the null hypothesis that the difference (C-T) is equal to zero.

Standard deviations in parentheses; sample sizes in brackets

Notes: Racial/ethnic indicators are not mutually exclusive and do not sum to 1 across groups. This table includes multiracial and White Hispanic students with potentially threatened students, as in our main specifications.

Analyses

All analyses were based on intention-to-treat estimates of the effect of self-affirmation, which assess the impact of assignment to the treatment group and therefore reflect the policy-relevant impacts of providing the self-affirmation (Borman, 2002). We calculated effects overall and within theoretically relevant subgroups. Estimates were based on the following general multilevel model of treatment effects:

| (1) |

In this model, Yij is the observed outcome for student i in school j, Treatmenti is the randomly assigned self-affirmation treatment status for student i, Xi is a vector of pre-treatment covariates (grade 6 outcome, gender, limited English proficiency, special education, and free lunch eligibility), ηj is the residual component for school j, and εi is the residual for student i. Because the treatment was randomly assigned to each student, β1 provides an unbiased estimate of the effect of the self-affirmation intervention without additional controls, but we included a pretreatment achievement measure and additional covariates, Xi, to increase the precision of this estimate.2

Within this basic framework, we conducted specific analyses to explore potential differences between the two studies, including alternate outcomes and estimates for theoretically relevant sub-groups. Many of our analyses tested for differences in effects between cohort 1 and cohort 2 by estimating cohort-by-treatment interactions in pooled models with all observations, and we also estimated overall effects with the pooled data. We provide additional details for specific analyses as we present the results below.

Results

Estimated Impacts of Self-Affirmation

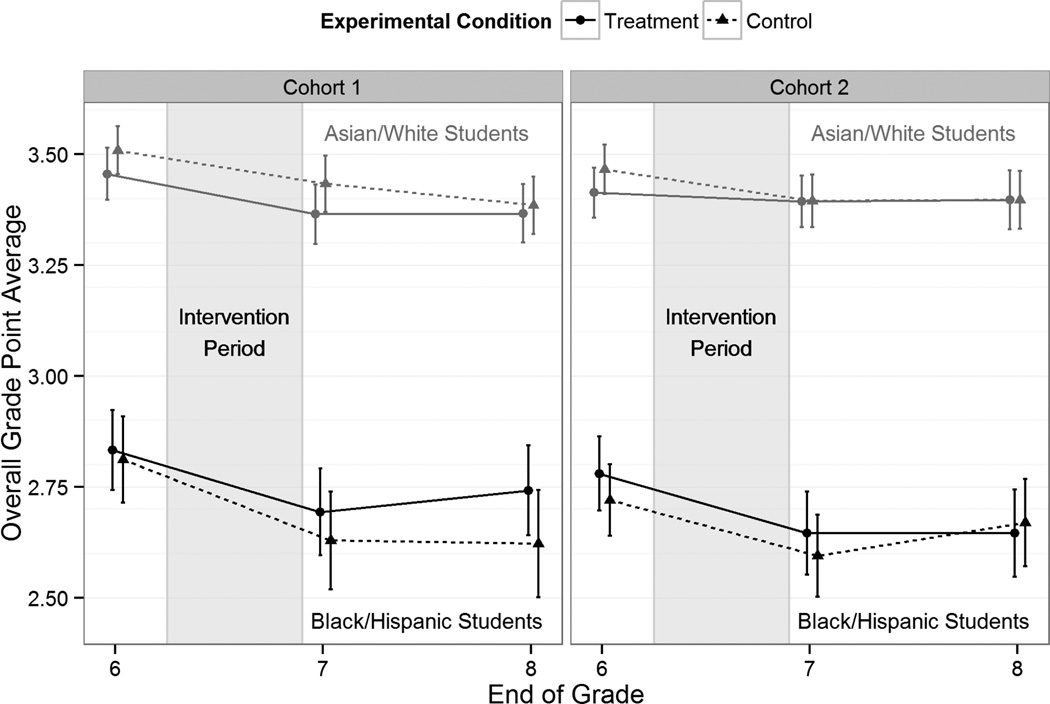

The raw pattern of results for the new study of self-affirmation (cohort 2) for the focal outcome (Grade Point Average) is presented in the right panel of Figure 2. As expected, there were no effects of the intervention on the performance of Asian and White students, who are not hypothesized to be subject to the same types of identity threats in school as are the other groups. Potentially threatened groups (Black and Hispanic) performed worse overall, but the differences between treatment and control groups were similarly small in both 7th and 8th grade. To estimate treatment effects as precisely as possible for this targeted group, we used multilevel models of the self-affirmation intervention, controlling for pre-treatment student characteristics. Estimates for all outcomes were negative, but none were statistically different from zero (Table 2). The GPA effect in grade 7 was approximately zero (d=−0.002), while the effect in grade 8 was nominally negative (d=−0.072). Because the sample was quite large, these null results rule out (at the 0.05 significance level) impacts of 0.10 standard deviations or greater on GPA in grades 7 and 8.3 Results for standardized achievement outcomes were similar. Concerning our first research question, therefore, we found no evidence of treatment benefits for the targeted population in the new study.

Figure 2. Yearly Grade Point Average (with 95% Confidence Intervals) by Race/ethnicity and Experimental Condition.

Notes: Randomly assigned self-affirmation writing interventions were administered throughout the 7th grade year. No effects of the treatment are hypothesized for Asian and White students, who are not subject to general negative stereotypes about academic ability. Raw treatment vs. control differences are statistically different from zero only for Black and Hispanic students in Grade 8 in cohort 1. The treatment benefits in that cohort are statistically different than the small negative effect observed in cohort 2. See Table 2 for standardized estimates and Table A3 for results from a pooled treatment effects model.

Table 2.

Standardized Self-affirmation Treatment Impact Estimates for Black and Hispanic Students

| Cohort 1 (N = 331) |

Cohort 2 (N = 449) |

p-value for Difference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| GPA, Grade 7 | 0.062 | 0.057 | −0.002 | 0.043 | 0.363 |

| GPA, Grade 8 | 0.152 | 0.070 | −0.072 | 0.058 | 0.013 |

| WKCE Mathematics, Grade 7 | 0.072 | 0.059 | −0.085 | 0.047 | 0.037 |

| WKCE Mathematics, Grade 8 | 0.101 | 0.070 | −0.080 | 0.044 | 0.023 |

| WKCE Reading, Grade 7 | −0.034 | 0.069 | −0.005 | 0.055 | 0.737 |

| WKCE Reading, Grade 8 | −0.030 | 0.071 | −0.005 | 0.056 | 0.781 |

SE = Standard Error; GPA = Overall grade point average; WKCE = Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination

Note: All estimates are based on models including controls for pre-treatment measures of the outcome and baseline student characteristics (gender, special education status, Limited English Proficiency designation, and eligibility for free or reduced price lunch). See Table A3 for full pooled model results.

Although not our primary focus, we also tested three additional findings reported by Cohen et al. (2006). First, we found no evidence of greater benefits of the intervention for potentially threatened students; the estimated interaction pointed in the opposite direction in our preferred specification but was not significantly different from zero (p=0.15). Second, we found no evidence of differential effectiveness by prior academic performance. Following the procedures described by Cohen et al. (2006), we created tercile groups based on 6th grade GPA, within the potentially threatened and potentially non-threatened groups. We failed to reject the null hypothesis that treatment impacts were equivalent across all three groups (p=0.20). We also found no evidence of differential impacts by prior achievement among White and Asian students (p=0.73). Finally, we tested for evidence of an improved trajectory of performance throughout the year. Considering students’ grades in each of the four terms of the school year, we tested for an interaction between treatment and term. GPA declined by 0.05 GPA points per term on average among Black and Hispanic students, but there was no difference by experimental condition (p=0.77).

Comparing Self-affirmation Effects across Studies

The results above led us to ask whether the null effects in the current study (cohort 2) differed from those in the previous research in the same setting (cohort 1). A first question was whether the benefits observed previously (Borman et al., 2016) were detectable in the year following the intervention. We analyzed data from the subset of students from the prior study with valid observations in grade 8, using parallel procedures to those above (estimates summarized in Table 2).4 We found that self-affirmation group students received significantly higher grades in 8th grade (d=0.152), bolstering the interpretation that the intervention led to detectable increases in academic performance for African American and Hispanic students. However, when we combined cases across studies, we did not find a statistically significant average self-affirmation treatment effect (grade 7: p = 0.54, grade 8: p = 0.58).

To address our second research question, we estimated the difference between self-affirmation impacts for cohort 1 and cohort 2 by pooling data from both samples and including cohort interactions with all covariates. We found that in several cases the null effects for cohort 2 were distinguishable from comparable effects for cohort 1. For the primary outcome, 8th grade GPA, the standardized cohort 2 estimate was small and negative (d=−0.072), while the cohort 1 estimate was positive (d=0.152), and we could reject the null hypothesis that effects were equal (p = 0.013).5 We also found statistical evidence of differences between the treatment effects across cohorts for the two supplementary mathematics state test score outcomes (p = 0.037 in Grade 7, p = 0.023 in Grade 8), although only the grade 8 mathematics cohort effect difference would be statistically significant if the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied to both estimates in this mathematics domain.

These results were robust across different specifications of the treatment effects model. In addition to our preferred specification, which included the full set of individual control variables, we also estimated impacts in models with no covariates and with controls only for the pre-treatment outcome measure. Figure 3 summarizes results of these three specifications (represented by symbol shapes) for the focal group and comparison (Black/Hispanic students, combined control; Panel B1), as well as for alternate comparisons testing theorized moderators (discussed in the corresponding sections below). Appendix Figure A1 presents comparable results for grade 7 overall grade point average. In all cases, results were substantively robust across all covariate specifications, although predictably less precise for the models omitting the alternate control cases.

To summarize results to this point, the two studies provided diverging pictures of the impacts of the self-affirmation intervention on Black and Hispanic students’ academic outcomes. For cohort 1, benefits in GPA persisted in the academic year following the intervention. For cohort 2, however, we found no evidence of benefits of the intervention. Moreover, we rejected the null hypothesis that impacts were equal in both studies, despite being conducted in the same research setting. These results motivated our final research question: do the currently theorized moderators of self-affirmation explain the differences in treatment effects across the two cohorts? In the remaining sections, we focus on the primary outcome measure, grade 8 GPA, and assess potential explanations for the decline in treatment effects from cohort 1 to cohort 2.

Differences in the Delivery of Self-affirmation: Intervention Design

Research projects, like educational practice, evolve over time for pragmatic reasons. For instance, in previous self-affirmation studies, investigators adjusted the frequency and content of intervention exercises as they were implemented across successive cohorts and in new settings (Cohen et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2013). In the current study, two design changes between the first and second cohort created differences in the delivery of the self-affirmation activities that potentially explain differential impacts: a shift in comparison group activities for one of the four exercises and a pre-intervention survey, which was added in the second study.

First, a randomly selected half of the control group was assigned a different first exercise in the cohort 2 study, compared to cohort 1. All control students were assigned the original control activity in cohort 1, which directed students to select values that were unimportant to them and write about why these values may be important to someone else. Half of the control group did the same in cohort 2, but half was randomly assigned to an alternate control activity for exercise 1 that asked students to write about what they did over the summer. Alternate control conditions were added in response to reported struggles of some students with the original “least important values” control activity. The alternate control writing prompt was modeled after typical classroom free-writing prompts, and was administered to non-consented students in both years. This prompt is “neutral” in the sense that it does not explicitly refer to values, but students could, potentially, write self-affirming responses (see “Student Experiences” section below). A random half of the control group in both cohorts completed a comparable alternate activity for exercise 2, which asked students to describe how to complete a procedural task, such as how to open a locker.

To assess whether this modification in the control regime contributed to different intervention impacts, we focused on the randomly selected half of the control group in both cohorts that received exactly the same sequence of exercises, which directly followed the original design (Cohen et al., 2006). These estimates are presented in Figure 3 in subpanel 2 for each sample (labeled “Original Control”). The cohort-by-treatment interaction estimates were substantively unchanged in these analyses, though less precise owing to the smaller sample size, implying that the slight procedural change does not explain the drop-off in impact in the second cohort. Since we found no evidence of differences between the two control groups, we pooled both groups for all reported analyses, unless noted otherwise.

A second design change for the second cohort was the administration of a 15–20 minute survey by researchers in classrooms in the first week of school. Interaction with research team members was similar for both studies because, for cohort 1, researchers visited classrooms during this time to collect student assent forms. In both assent (cohort 1) and survey (cohort 2), researchers did not connect these overt research activities with the writing exercises, the first of which was administered on average one week later. Students were told in both cases that the study was interested in their thoughts and opinions as middle school students. The survey included items about individual characteristics (e.g., locus of control, self-complexity, and social belonging) but omitted any specific reference to racial identity, stereotypes, or self-affirmation, which might have primed students to experience identity threats.

It is theoretically possible that survey prompts about social-psychological constructs like social belonging could change how students respond to the self-affirmation exercises. Although we could not directly assess whether the inclusion of the survey accounted for lower benefits for cohort 2, this explanation is unlikely for two reasons. First, to explain the decline in our setting, prior surveys would needed to have muted the treatment contrast (such as by inoculating treatment students from self-affirmation benefits), but the original large and persisting impacts were found in the presence of a pre-survey (Cohen et al., 2009). Based on this result, we might have expected the largest benefits for cohort 2. Second, the prior surveys were distinct from the self-affirmation exercises, fielded on a different day by the researchers, instead of teachers, and not explicitly linked to the exercises. Therefore social psychological responses activated by the survey would have to persist over time and remain relevant for a separate task. While future research is necessary to test whether such prior prompts modify self-affirmation benefits, we note that if such brief, distinct stimuli moderate self-affirmation impacts, then there are many other school experiences that are also likely to matter. If true, the effects of the self-affirmation intervention would be extremely difficult to predict a priori.

Differences in the Delivery of Self-affirmation: Student Experiences

One potential explanation for heterogeneity in treatment effects between the two studies is a decline in the quality of students’ experience of the activities related to implementation. Although formal and informal procedures were consistent, the hypothesized psychological processes may be sensitive to subtle changes in delivery (Yeager & Walton, 2011), and it is possible that small changes in classroom procedures had large consequences for effectiveness. For instance, if teachers presented the materials differently in the second cohort, then fewer students may have engaged in genuine self-reflection. As discussed in the “Fidelity” section, no direct observations of classroom implementation were collected (the activities were intended to be part of regular classroom activities and not to be associated with research). Instead we conducted three indirect tests of implementation differences as explanations for differential benefits between cohorts: changes in theorized features of implementation, changes in implementing teachers, and changes in students’ written responses to the intervention.

First, we noted three theoretically important features of the self-affirmation writing intervention design: that activities are administered during targeted times of potential stress, especially early in the school year (Cook et al., 2012; Critcher et al., 2010), that activities are not explicitly presented as externally imposed (Silverman et al., 2013), and that activities are not presented as being beneficial to students (Sherman et al., 2009). We documented that that these features of implementation did not vary (or improved) between cohorts. With respect to timing, 91% of classrooms for cohort 1 administered exercise 1 prior to the targeted first formative standardized assessment of the year, and 81% administered exercise 2 prior to the state standardized testing. The comparable numbers in cohort 2 were 91% and 97%, respectively. Based on retrospective self-reports from teachers provided at the end of the school year, we also found more faithful implementation for the second cohort. In cohort 1, 31.1% of students were taught by a teacher who reported describing the activities as “good for” them, while 42.2% were taught by a teacher who reported explaining the activities as connected to a research study. Both figures improved for cohort 2: 13.9% for “good for” instructions and 24.6% for mention of a research study. With the caveats outlined in the “Fidelity” section, these reports show no indication of poorer implementation in cohort 2. In other words, while imperfect delivery of the exercises may explain some of the attenuation of self-affirmation effects, these features did not explain the difference in effects between the two studies here.

Second, we considered whether changes in implementing teachers accounted for the decline in benefits. Due to staffing changes, 77% of the Black and Hispanic students in cohort 1 and 60% in cohort 2 completed the exercises with a teacher who implemented in both studies. If teacher fatigue with the study adversely affected implementation, then impact declines should have been largest among the “both-cohort” teachers. Conversely, if unique cohort 1 teachers were especially effective, the declines should have been be largest among “single-cohort” teachers. We found no evidence for either hypothesis (see Appendix Table A4). Treatment by cohort interactions were substantively equivalent in both sub-populations (−0.196 grade points for the both-cohort teachers; −0.188 for the single-cohort teachers) and these interactions were statistically indistinguishable from one another (p = 0.99).

Finally, we tested whether students’ written responses differed across the two cohorts of the study. While features of the written responses are imperfect proxies for the desired self-reflection, they provide an indication of whether the quantity or quality differed across cohorts. The two most basic measures of overall engagement were comparable in both studies: exercise completion and words written. A high proportion of students completed the activities, ranging from 85–95% (Table A5, Column 1). Completion did not differ by experimental condition or cohort. In supplementary analyses, we found that completers tended to have higher prior GPA than non-completers—no other baseline covariate predicted completion—but this difference was not distinguishable between cohorts.

The relative length of students’ responses was consistent across cohorts too, after accounting for variation due to differences in prompts over time (Columns 2 and 3). The only treatment-control difference between cohorts was in mean words written for exercise 1 (Panel A), and this was completely explained by the randomly assigned “neutral” comparison group; students were more prolific when writing about their summer (in cohort 2) than about an unimportant value. Comparing students with the same, “original” prompts (Column 3), there were no cohort differences. By these measures, basic engagement with the activities was consistent across the two cohorts.

Analyses of the qualitative measure of students’ responses to the exercises (introduced in the “Fidelity” section above) implied that treatment caused students to engage in much higher rates of affirmation across all exercises in both studies.6 The estimates are based on linear probability models, so the coefficient of 0.709 (Table A5, Panel B, Column 4) implies that the chance of affirmation writing was 71 percentage points higher in the treatment group in cohort 1 for exercise 2. The interaction coefficient (0.0796) implies that this treatment effect was actually higher in the second cohort, at a significance level of p < 0.1. Exercise 1 was again an exception, but the difference was solely explained by the modifications to the control group (see Column 5). Not surprisingly, the control group in cohort 2, including students who wrote about their summer, was more likely to write affirming statements, which others have noted is a risk in choosing that type of comparison activity (Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, 2000). Even so, treatment impacts on self-affirming writing were greater than 40 percentage points (0.427=0.721–0.294) in the second cohort overall.

On balance, analyses of implementation features, consistent teachers, and direct measures of intervention responses did not support the hypothesis that declines in implementation quality could explain lower benefits for cohort 2. In particular, responses to the exercises were strong overall, and comparable between cohorts. These results cannot rule out the possibility of differential psychological responses to the exercises in the two implementations, which deserves attention in future research. However, for this possibility to be true, the association between key psychological responses and the desired features of students’ written responses must have changed between cohorts. The more parsimonious explanation is that declines in implementation did not account for lower effectiveness.

Individual Student Differences

The success of social-psychological interventions depends fundamentally on individual characteristics. Self-affirmation is only hypothesized to help students who are subject to identity threat, and students may also differ in how they respond to the specific reflective writing activity. Meaningful individual differences between cohorts could have resulted from sampling variability and/or because the second cohort study sample was larger, including 36% more potentially threatened students (449 vs. 331 in cohort 1), and different in terms of mean individual characteristics (see Table 1), due to more successful recruitment. We used three strategies to test for individual-level explanations of cohort differences: effects in theoretically sensitive subgroups, observable differences between the two cohorts, and the plausible influence of unobserved heterogeneity.

One implication of theorized moderation of self-affirmation benefits by individual characteristics is that results should be consistently stronger, and therefore less variable across cohorts, in subpopulations where academic stereotype threats are hypothesized to be most salient. We tested effects in two such subpopulations: students identified as only Black or Hispanic (excluding multiracial students), who may identify more strongly with a stereotyped identity, and Black/Hispanic Males, who may be subject to the most acute general academic stereotypes in middle school (Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008). Results are summarized in Panels C and D of Figure 3. Contrary to the individual difference hypotheses, differential effects across cohorts were similar in both of these subpopulations, even though lower precision in the male subgroup led similar size differences to be statistically insignificant.

We also tested all observed individual student characteristics as explanations of cohort differences. For individual characteristics to explain the decline in treatment effects, differences between the two samples must have been related to treatment effect heterogeneity. We did find some descriptive differences between studies (see Table 1): the sample for cohort 2 had more female students (52.6% vs. 49.8%; p = 0.03), lower 6th grade GPAs on average (2.78 vs. 2.85; p = 0.11), and more students eligible for free or reduced price lunch (85.1% vs. 80.1%; p = 0.07). However, we found no statistically significant interaction between treatment and individual characteristics (grade 6 grade point average, gender, English proficiency, or Special Education designation) in either cohort, suggesting little opportunity for individual observed characteristics to explain different treatment effects. Not surprisingly, when we re-weighted individual cases in each cohort to balance populations in terms of each of these observable characteristics (for instance, giving greater weight to poor students in cohort 1, who were relatively underrepresented in that sample), the effect estimates in each cohort were substantively unchanged (see Table A7).