Abstract

Blunted reward response appears to be a trait-like marker of vulnerability for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). As such, it should be present in remitted individuals; however, depression is a heterogeneous syndrome. Reward-related impairments may be more pronounced in individuals with melancholic depression. The present study examined neural responses to rewards in remitted melancholic depression (rMD; N = 29), remitted non-melancholic depression (rNMD; N = 56), and healthy controls (HC; N = 81). Event-related potentials to monetary gain and loss were recorded during a simple gambling paradigm. rMD was characterized by a blunted response to rewards relative to both the HC and the rNMD groups, who did not differ from one another. Moreover, the rMD and rNMD groups did not differ in course or severity of their past illnesses, or current depressive symptoms or functioning. Results suggest that blunted response to rewards may be a viable vulnerability marker for melancholic depression.

Keywords: reward processing, melancholia, vulnerability, depression

Introduction

Despite the prevalence and public health impact of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Greenberg et al., 1993; Mathers et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2013), few reliable mechanisms of vulnerability for the disorder have been identified, due, in part, to the heterogeneity of the syndrome (Cuthbert, 2014; Cuthbert & Insel, 2013; Helzer et al., 2006; Klein, 2008). Different symptoms and symptom clusters subsumed under the MDD diagnosis appear to have distinct etiologies (Day et al., 2015), courses (Angst et al., 2007; Lux & Kendler, 2010), and biological correlates (Pizzagalli et al., 2004; Shankman et al., 2011). Examining more specific processes and symptom clusters within the category of depression may be useful in refining psychological and biological phenotypes and identifying vulnerability markers (Insel et al., 2010; Shankman and Gorka, 2015).

Dysfunctions in reward responding, a process which relies heavily on dopaminergic (DA) activity in the frontostriatal system (Berridge, 2007; Schultz et al., 1995), appear to play a central role in the pathophysiology of at least some expressions of depression (Hanson et al., 2015; Romens et al., 2015). Blunted striatal response to rewards has been observed in currently depressed individuals (Forbes et al., 2009; Keedwell et al., 2005; Olino et al., 2011; Pizzagalli et al., 2009), and hypoactivation of this system appears to relate specifically to reduced hedonic capacity, and not other symptoms of depression or anxiety (Keedwell et al., 2005; Wacker et al., 2009). Furthermore, there is evidence that both adults (Henriques and Davidson, 2000; Pizzagalli et al., 2005; Steele et al., 2007) and youth (Forbes et al., 2006; Forbes et al., 2009) with depression are less sensitive to the effect of rewards in shaping behavior.

Moreover, reward-related impairments appear to be relatively stable over time (Oquendo et al., 2004; Shankman et al., 2013), suggesting trait-like qualities. Consistent with this, depression-linked abnormalities in reward processing appear to be evident even in the absence of observable psychopathology: Children of depressed parents, who are at elevated risk for depression (Gotlib et al., 2014; Weissman et al., 2006), have shown blunted reward responding in the absence of observable symptoms (Gotlib et al., 2010; Kujawa et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2013). Moreover, reward-processing dysfunction can prospectively predict the onset of depression (Bress et al., 2013; Forbes et al., 2007; Hanson et al., 2015; Rawal et al., 2013), and may mediate the association between early stressors and later depressive symptomatology (Hanson et al., 2015; Romens et al., 2015), suggesting a mechanistic role.

However, not all individuals who meet criteria for depression, or who are at risk for depression, show evidence of blunted reward responding (Chen et al., 2000; Foti et al., 2014; Shankman et al., 2007; Shankman et al., 2011), suggesting the necessity of examining more specific sub-groups and symptom clusters. In particular, although depression in general has been associated with DA-linked reward processing impairments, DA functioning may be most impaired in melancholic depression (Baumeister and Parker, 2012; Parker, 2007; Parker et al., 1995), a specifier within the MDD category. Indeed, the essential symptom of melancholia is pervasive anhedonia, or the inability to respond to positive events in the environment (Parker, 2007; Parker et al., 1995), and there is evidence that blunted response to rewards might be most pronounced in this subtype (Foti et al., 2014; Haslam and Beck, 1994; Klein, 1974; Leventhal and Rehm, 2005; Shankman et al., 2011). Biomarkers of reward dysfunction might therefore be present in individuals at risk for melancholic depression.

Remitted depressed individuals are helpful targets of research concerned with vulnerability markers, in that, while they are currently well, they remain vulnerable to relapse of illness (Horwath et al., 1992). Use of remitted depressed individuals thereby permits investigation of neural correlates of vulnerability, but mitigates potential confounding effects of symptom severity and mood states in currently depressed individuals. Neural response to reward observed during periods of remission may therefore provide useful information about trait-like vulnerabilities and the diathesis of the disorder (Jacobs et al., 2014). In fact, while there is evidence that some neural abnormalities normalize in remission (Bench et al., 1995; Brody et al., 1999; Mayberg et al., 2014), persistent hypoactivation of reward networks has been observed in remitted depressed individuals (Dichter et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2009; Whitton et al., 2015), as have impairments in reinforcement learning (Pechtel et al., 2013). On the other hand, other studies have reported normal hedonic capacity in remitted depression (Dichter et al., 2009; McFarland and Klein, 2009), or even enhanced reward anticipation (Ubl, et al., 2015) suggesting state-linked abnormalities. Diagnostic heterogeneity may explain these mixed results.

The present study therefore sought to measure neural response to rewards in a sample of individuals with remitted melancholic and remitted non-melancholic depression. The index of neural response to rewards used in the present study was the Feedback Negativity (FN), an event-related potential (ERP) component which is increasingly used in research on reward processing (Carlson et al., 2011; Foti et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2012). The FN peaks approximately 250-300 ms at frontocentral recording sites following the presentation of feedback (Holroyd and Coles, 2002; Miltner et al., 1997), and has typically been conceptualized as a negativity elicited by loss feedback that is absent following gain feedback. However, recent evidence suggests that the apparent differentiation in the ERP between gain and loss trials is driven by variation in a reward-related positivity (called the RewP; Proudfit, 2014) that is larger and more positive for rewards than non-rewards (Carlson et al., 2011; Foti et al., 2014; Foti et al., 2011b; Holroyd et al., 2008). The magnitude of the RewP is also moderated by variation in genes governing the synaptic degradation of dopamine (Foti and Hajcak, 2012), and a larger RewP is associated with increased striatal response to rewards (Becker et al., 2014; Carlson et al., 2011; Foti et al., 2014).

A blunted RewP has also been observed repeatedly in individuals with current depression (Bress et al., 2012; Foti et al., 2014; Foti and Hajcak, 2009; Liu et al., 2014), as well as in individuals vulnerable to depression (Foti et al., 2011a; Kujawa et al., 2015; Kujawa et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2015). A smaller RewP also appears to prospectively predict the onset of depression, even accounting for other known risk factors (Bress et al., 2013), suggesting that the blunted RewP may be not only a correlate of depression but may also represent a neural marker of vulnerability for depressive disorders.

To date, only one study has examined ERPs to loss and gain feedback in remitted depression—and found that individuals with remitted depression had a larger FN elicited by loss trials in a reinforcement learning task compared to controls (Santesso et al., 2008). However, this study did not examine ERPs to reward trials, nor did it account for diagnostic heterogeneity. Examination of the association between specific symptom clusters and the RewP may be particularly informative in light of a recent study in currently depressed individuals, which found that the blunted RewP related specifically to symptoms of melancholia, and was not associated with other depressive symptoms and specifiers (Foti et al., 2014).

The present study therefore sought to examine whether the blunted RewP might represent a state-independent vulnerability marker for melancholic, but not other forms of depression. We examined the magnitude of the RewP elicited in a simple gambling task in a sample of individuals with remitted MDD (melancholic type), remitted MDD (non-melancholic type), and healthy controls (HC). We predicted that the magnitude of the RewP would be blunted in remitted melancholic depression relative to both controls and remitted non-melancholic depression. In order to explore whether the blunted RewP was a state or trait characteristic, we also compared current symptoms and functioning between the two remitted depressed groups.

Methods

Participants

The participants in the current sample were selected from a larger sample of siblings (see e.g., Weinberg, Liu, Hajcak, & Shankman, 2015; Gorka, Liu, Daughters, & Shankman, 2015 for other reports on this sample). We recruited participants between the ages of 18 and 30 from the community and area mental health clinics (via fliers, Internet postings, etc.) on the basis of symptoms of anxiety and depression. We used minimal symptom-based inclusion and exclusion criteria, and aimed to recruit a sample with a broad range of internalizing symptomatology. However, to ensure the clinical relevance of the sample, we also oversampled from individuals with severe psychopathology. Thus, the goal was recruit a sample with normally distributed internalizing symptoms but with a mean more severe than the mean of the general population. Prior to their involvement in the study, participants were screened via telephone using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), a brief (21-item) measure of broad internalizing psychopathology (the measure was used to ensure that the sample had the above-mentioned distribution on internalizing symptoms). As manic and psychotic symptoms have been shown to be separable from internalizing disorders (Watson, 2005), subjects were excluded during screening if they had a personal or 1st degree family history of a manic/hypomanic episode or psychotic symptoms, assessed via items from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996). Participants were also excluded if they were unable to read or write English, had a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, or were left-handed.

Participants were included in the current analyses if a) they did not meet criteria for any current or lifetime anxiety, depressive, alcohol, substance, PTSD, and eating disorder assessed in the SCID (Healthy Controls; HC; N = 71), or b) they met lifetime—but not current—criteria for MDD (N = 85). The remitted depressed group was then divided into individuals who met lifetime criteria for DSM-IV melancholic depression (rMD, N = 29), and individuals who did not meet criteria for melancholic depression (rNMD, N = 56). Of those with remitted non-melancholic depression, 10 met criteria for atypical depression, and the remaining 46 met criteria for unspecified major depressive episodes. The final sample was 64.8% female, and was racially diverse (42.1% Caucasian-American, 22.6% Hispanic, 12.6% African-American, 15.1% Asian, 3.1 % Middle Eastern, .6% “Other”, and 2.5 % Mixed Race), well-educated (47.8% had completed at least some college education; 18.2% had completed four years of college) and relatively young (Age M = 22.53, SD = 3.17). All procedures were approved by the University of Illinois–Chicago Institutional Review Board, and all research was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

All clinical diagnoses of current and lifetime anxiety, depressive, alcohol and substance, PTSD, and eating disorders were assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID; First et al., 1996), which was administered to every participant. The SCID included items that assessed melancholic MDD using DSM-5 criteria. Current clinician-rated global assessment of functioning (GAF) was also made in the course of the SCID. Diagnosticians were trained to criterion on the SCID and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist (SS). In order to assess prior episodes of depression, participants were asked to recall the worst past episode they had ever experienced. Current and lifetime diagnoses of Substance Use Disorders (SUD; Including Alcohol Use Disorders), and Anxiety Disorders were also collected in the course of the SCID. In addition to diagnoses, interviewers dimensionally assessed functional impairment and subjective distress during the past depressive episode that the remitted depressed participants identified as their most severe. Interviewers made ratings for impairment in the domains of social, occupational, and daily life, as well as perceived distress, along a nine-point scale ranging from 0 (None) to 8 (Severe). The anchors for the scale were adopted from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV; Brown et al., 1994) in which a 2 or higher was clinically significant distress or impairment. Severity of worst past episode was calculated as the mean of these impairment ratings.

Current depression and anxiety symptoms (past two weeks) were also assessed in all participants using the expanded Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II; Watson et al., 2007; Watson et al., 2012). We report here on the following eleven subscales associated with unipolar depression and DSM-V anxiety disorders: General Depression, Dysphoria, Lassitude, Insomnia, Suicidality, Appetite Loss, Appetite Gain, Ill-Temper, Well-Being, Social Anxiety, and Panic.

Procedure

Participants completed a battery of tasks and the order was counterbalanced across subjects. Results from other tasks will be reported elsewhere (e.g., Gorka et al., 2015; Weinberg, Liu, & Shankman, 2015). The present task was administered on a Pentium class computer, using the stimulus presentation software Presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.).

Task and Materials

The reward task was a simple guessing task which has been used in other studies concerned with reward processing (Foti et al., 2011b). The task consisted of 60 trials, presented in three blocks of 20. At the beginning of each trial, participants were presented with an image of two doors and were instructed to choose one door by clicking the left or right mouse button. The doors remained on the screen until the participant responded. Next, a fixation mark (+) appeared for 1000 ms, and feedback was presented on the screen for 2000 ms. Participants were told that they could either win $0.50 or lose $0.25 on each trial. A win was indicated by a green “↑,” and a loss was indicated by a red “↓.” Next, a fixation mark appeared for 1500 ms and was followed by the message “Click for the next round,” which remained on the screen until the participant responded and the next trial began. Across the task, 30 win and 30 loss trials were presented in a random order.

Psychophysiological Recording, Data Reduction and Analysis

Continuous EEG recordings were collected using an elastic cap and the ActiveTwo BioSemi system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Sixty-four electrodes were used, based on the 10/20 system, as well as two electrodes on the right and left mastoids. Electrooculogram (EOG) generated from eye movements and eyeblinks was recorded using four facial electrodes: horizontal eye movements (HEM) were measured via two electrodes located approximately 1 cm outside the outer edge of the right and left eyes. Vertical eye movements (VEM) and blinks were measured via one electrode placed approximately 1 cm below the left eye and electrode FP1. The data were digitized at a sampling rate of 1024 Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with −3dB cutoff point at 208 Hz. Each active electrode was measured online with respect to a common mode sense (CMS) active electrode, located between PO3 and POz, producing a monopolar (non-differential) channel. CMS forms a feedback loop with a paired driven right leg (DRL) electrode, located between POz and PO4, reducing the potential of the participants and increasing the common mode rejection rate (CMRR). Offline, all data were analyzed in Brain Vision Analyzer (BVA) and were referenced to the average of the left and right mastoids, and band-pass filtered with low and high cutoffs of 0.1 and 30 Hz, respectively. Eye-blink and ocular corrections were conducted per a modification of the Gratton, Coles, and Donchin (1983) algorithm, which accounts for both vertical and horizontal eye movements.

A semi-automatic procedure was employed to detect and reject artifacts. The automatic criteria applied were a voltage step of more than 50.0 μV between sample points, a voltage difference of 175 μV or greater within any 400 ms window within a trial, and a voltage difference of .50 μV or less within 100 ms intervals. The data were then visually inspected and any remaining artifacts (e.g., slow-wave activity, blinks that were not adequately corrected) were rejected.

The EEG was segmented into 1200 ms windows for each trial, beginning 200 ms before each response onset and continuing for 1,000 ms following feedback. A 200 ms window from −200 to 0 ms prior to feedback onset served as the baseline. The FN appears maximal around 300 ms at central sites; therefore, the time-window scored FN was scored as the average activity at electrode sites Cz and FCz, between 220 and 360 ms.

To examine potential associations between melancholia and ERPs elicited by feedback, we used the Mixed Models Linear procedure in SPSS version 20 to conduct repeated-measures analyses of variance to compare neural response to rewards and non-rewards. History of Melancholic Depression (0 = controls, 1 = non-melancholic depression, 2 = melancholic depression), Psychiatric medication usage (Yes/No) and feedback condition (Rewards vs. non-rewards) were fixed factors in a full factorial linear mixed model MANOVA design. Because there is evidence that gender (Kujawa et al., 2014), Alcohol and/or Substance Use (e.g., Parvaz et al., 2012), and Anxiety Disorders (Guyer et al., 2012; Morris & Rottenberg, 2015) can also be associated with aberrations in reward processing, each of these was also entered as a fixed factor. Alcohol and/or Substance use and Anxiety disorders were scored as dichotomous variables indicating whether individuals met lifetime criteria (i.e., current or past) for the diagnoses. Because siblings violate the assumption of independent sampling, we used the MIXED procedure to account for sibling similarity. This provides an appropriate adjustment for degrees of freedom and thus statistical significance in each analysis. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation was utilized to account for missing data. REML yields unbiased estimates if data are missing at random (Roderick et al., 1986), and produces estimates that agree with ANOVA estimates when data are balanced. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons were used to test for group mean differences (i.e., melancholic depression vs. controls, non-melancholic depression vs. controls, melancholic depression vs. non-melancholic depression).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Means for current Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), current Axis I diagnoses, and current symptoms endorsed on the IDAS are presented in Table 1. As indicated in Table 1, although both remitted depressed groups reported lower GAF and more current symptoms of depression, social anxiety and panic than the HC group, the two remitted groups were within one standard deviation of the means for non-clinical samples reported in Watson and colleagues (2007). The two remitted depressed groups did not differ from one another on any variables related to current functioning, current or prior Axis I diagnoses, previous course of the depression, the severity of their worst episode, or time spent in remission (all p values > .20). The two remitted depressed groups also did not differ in lifetime SUD/AUD diagnoses (rMD N = 18, rNMD N = 24), or in lifetime diagnosis of Anxiety Disorder (rMD N = 5, rNMD N = 4).

Table 1.

Demographic information, performance variables, neural responses, means for subscales of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II), and clinical characteristics for the three groups.

| Healthy Controls (N = 81) |

Non-Melancholic Depression (N = 56) |

Melancholic Depression (N = 29) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 21.78 (2.85) | 23.05 (3.26) | 23.34 (3.34) | |

| Sex (% female) | 60.5 | 69.6 | 57.7 | |

| ERPs (μV) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Loss | 8.92 (4.82) | 9.64 (5.54) | 8.21 (6.69) | |

| Gain | 13.17 (5.25) a | 14.07 (6.85) a | 9.91 (7.66) b | |

| Loss Minus Gain | −4.28 (3.69) a | −4.61 (3.87) a | −2.01 (3.35) b | |

| Current Functioning | ||||

| GAF Mean (SD) | 85.19 (7.84)a | 64.39 (11.62) b | 60.07 (12.23) b | |

| Psychiatric Medication Use (N) | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| IDAS Scales | Mean (SD) | |||

| General Depression | 31.20 (7.35) a | 43.19 (14.02) b | 45.32 (15.12)b | |

| Dysphoria | 13.86 (4.26) a | 21.33 (8.30) b | 22.43 (9.29) b | |

| Lassitude | 10.30 (3.38) a | 14.33 (4.87) b | 14.43 (5.30) b | |

| Insomnia | 9.58 (3.81) a | 12.00 (5.58) b | 13.43 (5.15) b | |

| Suicidality | 6.18 (.63) a | 6.83 (1.65) | 7.79 (3.70) b | |

| Appetite Loss | 3.89 (1.77) a | 5.50 (2.56) b | 5.07 (2.62) b | |

| Appetite Gain | 3.80 (1.73) a | 4.72 (1.75) b | 4.68 (2.06) | |

| Ill Temper | 5.94 (2.27) a | 7.21 (2.62) b | 8.51 (4.20) b | |

| Well-Being | 26.05 (6.66) | 24.81 (6.25) | 23.25 (6.82) | |

| Social Anxiety | 7.15 (1.45) a | 10.61 (4.60) b | 10.96 (4.75) b | |

| Panic | 9.14 (2.49) a | 11.76 (4.25) b | 12.20 (4.37) b | |

| Diagnoses | N | |||

| Any current diagnosis | -- | 16 | 14 | |

| Substance/ Alcohol Use Disorder | -- | 6 | 1 | |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | -- | 1 | 0 | |

| Panic Disorder | -- | 1 | 0 | |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | -- | 3 | 5 | |

| Specific Phobia | -- | 3 | 5 | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | -- | 4 | 1 | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | -- | 5 | 1 | |

| Previous Course of Depression | Mean (SD) | |||

| # of MDD Episodes | -- | 2.14 (1.37) | 2.42 (1.45) | |

| MDD age of onset | -- | 18.8 (4.94) | 16.08 (5.11) | |

| Severity of worst past episode | -- | 4.87 (1.58) | 5.75 (1.16) | |

| Time in remission (months) | -- | 27.33 (26.19) | 30.70 (37.99) |

Note. If no superscripts appear, the groups did not differ significantly on the measure. Values with different superscripts were significantly different at p < .05 using post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons or χ2 ; IDAS = Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms; GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder

Association between neural response to rewards, loss, and melancholic depression

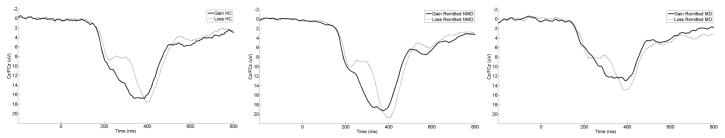

Figure 1 displays grand average response-locked ERPs at a pooling of Cz and FCz, where the non-reward minus reward difference was maximal across groups. Topographic maps from left to right for the HC, rNMD and rMD groups, depicting voltage differences (in μV) across the scalp for non-reward minus reward feedback in the time window of the RewP are presented in Figure 2. Average ERP values are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Stimulus-locked ERP waveforms at an average of electrode sites Cz and FCz for Healthy Controls (HC), remitted Non-Melancholic Depressed (rNMD), and Melancholic Depressed (rMD) groups. For each panel, stimulus onset occurred at 0 ms. Per ERP convention, negative voltages are plotted up.

Figure 2.

Scalp topographies representing the RewP. These maps are derived from the average difference between conditions (non-reward minus reward response) from 220 to 360 ms and represent the Δ RewP for Healthy Controls (HC), Non-Melancholic Depressed (rNMD), and Melancholic Depressed (rMD) groups.

Gender significantly predicted neural response to feedback in that women (M = 12.08, SE = .94; 95% CI: 10.22, 13.94) had a more positive overall response (i.e., collapsing across reward and non-reward) than men (M = 9.07, SE = 1.19; 95% CI: 6.71, 11.42) F (1, 136.64) = 7.60, p < .01. However, gender did not significantly interact with feedback type to determine neural response F (1, 137.00) < 1. In addition, feedback type had a significant effect on neural response F (1, 137.00) = 95.74, p < .001, such that rewards (M = 12.41, SE = .98; 95% CI: 10.49, 14.34) elicited a larger positivity than non-rewards (M = 8.73, SE = .91; 95% CI: 6.94, 10.53). Psychiatric medications were not significantly associated with neural response F (1, 136.00) < 1. Lifetime diagnosis of SUD and/or AUD F (1, 136.84) < 1, Anxiety Disorders F (1, 136.31) = 1.88, p = .17, and Melancholic Depression F (2, 136.41) = 2.36, p = .10 did not significantly predict the overall neural response (i.e., collapsing across feedback types). Feedback type did not interact with lifetime diagnosis of SUD/AUD F (1, 137.00) < 1 or Anxiety F (1, 136.84) < 1 to determine neural response.

However, the effect of feedback was significantly qualified by an interaction with melancholic group F (2, 137.00) = 5.71, p < .01. This interaction was decomposed by two separate univariate tests comparing groups on neural response to gain and loss separately. The three groups did not differ significantly in the neural response to loss F (2, 163.00) < 1, but there were significant group differences in neural response to reward F (2, 163.00) = 4.43, p < .05. Post-hoc pairwise Bonferroni comparisons indicate that rMD individuals had a significantly blunted neural response to rewards compared to both the HC D = 3.49, SE = 1.37, p < .05 and the rNMD depressed group D = 4.16, SE = 1.44, p < .05. The rNMD group did not significantly differ from the HC group in their neural response to rewards D = .68, SE = 1.10, p = 1.00. 1

In order to examine whether these effects could be attributed to residual symptoms of anhedonia or other symptoms of depression, we repeated the analyses above, excluding factors that did not significantly relate to neural response (i.e., AUD/SUD, Psychiatric Medications, Anxiety Disorders), and controlling first for current levels of positive affect (PA; IDAS well-being), and then for current levels of depressive symptoms (IDAS Depression). After adjusting for PA, the results were as above: We observed a main effect of gender F (1, 141.00) = 4.88, p < .05, as well as a main effect of feedback type F (1, 142.00) = 104.70, p < .001. There was no significant main effect of melancholic group F (2, 141.26) = 1.87, p = .16, or of current levels of PA F (1, 140.12) < 1. PA also did not interact with feedback type F (1, 141.00) < 1. However, as above, the effect of feedback was qualified by an interaction with melancholic group F (2, 142.00) = 6.68, p < .01.

The effects also held after adjusting for other current symptoms of depression. We observed a main effect of gender F (1, 140.00) = 6.39, p < .01, as well as a main effect of feedback type F (1, 141.00) = 19.54, p < .001. Additionally, there was a significant main effect of current depressive symptoms F (1, 140.25) = 8.66, p < .05, as well as of melancholic group F (2, 140.12) = 2.98, p <.05. However, residual depressive symptoms did not significantly interact with feedback type F (1, 141.00) = 3.21, p = .09. And finally, even after adjusting for residual symptoms of depression, we observed a significant interaction between feedback type and melancholic group F (2, 141.00) = 5.49, p < .01.

Discussion

The present study was the first to examine the impact of diagnostic heterogeneity on neural response to rewards in remitted depression. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that individuals with rMD were characterized by a blunted neural response to rewards. These results suggest that blunted reward responsiveness persists in individuals with a history of melancholic MDD even several years after the last major depressive episode. These group-level results also remained significant after adjusting for residual current depressive symptoms in the two depressed groups and are consistent with previous evidence that impaired reward processing may be a trait marker that is insensitive to state-linked fluctuations (e.g., Foti et al., 2011a; Kujawa et al., 2015; Kujawa et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2015; Whitton, et al., 2015). Research focused on blunted reward response in remitted depression might therefore be helpful in targeting mechanisms of future relapse.

The present study also used individuals with remitted non-melancholic depression as a psychiatric comparison group, allowing us to control not just for history of psychopathology, but also course and severity of depressive episodes. As hypothesized, individuals in the rNMD group did not differ from never-depressed controls in their response to rewards. Moreover, individuals in the rMD group exhibited a blunted RewP relative to individuals in the rNMD group, and this blunting was observed despite the fact that the rMD and rNMD groups did not differ in terms of symptom severity, impairment, or comorbidity at the time of the visit. Moreover, the magnitude of the RewP was not significantly associated with self-reported symptoms. These data suggest that the blunted RewP we observed was not a state-effect reflecting the severity of subclinical symptoms of depression at the time of the assessment. The two remitted depressed groups also did not differ in the course, number, or severity of their previous depressive episodes, suggesting the blunted RewP in the melancholic depression group does not reflect the residual effect of a more severe course or episode.

Because the individuals in this study had already experienced at least one major depressive episode, these data alone do not suggest that the blunted RewP is an index of vulnerability for the first onset of melancholic depression. It is possible that particularities of prior melancholic illness—or prior psychological and pharmacological treatments—may have had an enduring influence on the magnitude of the RewP. For instance, there is some evidence that individuals with melancholic depression both experience higher levels of stress and are more sensitive to stress compared to individuals with other forms of depression (Harkness and Monroe, 2002, 2006), and stress has been shown to attenuate the RewP (Bogdan et al., 2011). However, in combination with previous evidence that a blunted RewP is evident in vulnerable but asymptomatic individuals (Foti et al., 2011a; Kujawa et al., 2015; Kujawa et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2015), and can prospectively predict the onset of depression (Bress et al., 2013), the results we present here suggest the blunted RewP is likely not merely a “scar” resulting from prior psychological distress. Future studies might examine the ways in which significant life stressors might influence the development of the RewP and depression, as well as the potential ways in which vulnerability reflected in the blunted RewP might interact with life stressors to predict the onset and course of depressive illness.

The present results may also be useful in explaining previous inconsistencies in the literature. Although some studies have found persistent reward hyporesponsiveness in euthymic remitted depressed individuals (Dichter et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2009; Pechtel et al., 2013; Whitton, et al., 2015), not all have (Dichter et al., 2009; McFarland and Klein, 2009; Ubl et al., 2015). However, these studies have typically not examined subtypes of depression. Combined with other studies demonstrating that alterations in the magnitude of the RewP are present in at-risk individuals (Bress et al., 2013; Kujawa, Proudfit, & Klein, 2014), the results of the present study suggest this trait-like blunting may specifically reflect risk for features of melancholic depression, and particularly anhedonia (Foti et al., 2014).

However, this is not to say that these trait-like vulnerability markers are immutable. An important consideration for future research will be whether observed abnormalities in the activity of reward processing systems in affected and at-risk individuals can be modified, and whether modification of the activity of this system could be clinically meaningful. For instance, Dichter and colleagues (2009) administered a brief Behavioral Activation Treatment therapy—which aims to increase engagement with pleasant events in the environment—to a sample of adults with MDD and found that neural response to rewards normalized. Therapies which aim to specifically modify attention to and sustained processing of rewards might be more effective at treating melancholic depression and/or preventing relapse in individuals in remission (Browning et al., 2012; McMakin et al., 2011).

Limitations of the study suggest directions for future research. First, the individuals in this sample were young adults and relatively psychologically healthy, and may not be representative of MDD or remitted MDD as a whole. The study also used a cross-sectional design, and relied on retrospective report of the worst episode of past depression. Given that some participants were reporting on a previous episode several years after it occurred, it is possible that some symptoms and the degree to which they were experienced are imperfectly recalled. Moreover, we would note here that the course of depression can be rather heterotypic over time, and that melancholic features assessed in a single worst past episode do not perfectly predict future melancholic episodes (e.g., Melartin et al., 2004). In the current study, we assessed the most severe previous episode, but it is possible that some individuals in the rNMD group had met criteria for melancholic depression while in a less severe episode. It is also possible that some of the individuals in the rMD group will not meet criteria for melancholia again, while some in the rNMD group will. All of these limitations suggest that prospective studies in vulnerable populations will be necessary to identify the stability of the effects observed in the current study, as well as possible contributions a blunted RewP might make to the onset of depression. Finally, the study did not include currently-depressed comparison groups, which might be useful in further clarifying state vs. trait influences.

In conclusion, the present study found that melancholic depression was specifically related to a blunted RewP, and, further, that this blunted RewP was evident even in the absence of clinically-significant levels of current pathology. Combined, this suggests the blunted RewP may be a viable vulnerability marker for a particularly pernicious subtype of depression (Angst et al., 2007). The RewP may therefore be a valuable measure in future studies that seek to identify vulnerable individuals, and may be helpful in informing prevention efforts and tracking treatment response.

Footnotes

The pattern of these results did not change when excluding the ten individuals in the non-melancholic depression group with remitted atypical depression.

Author Contributions: A.W. developed the manuscript concept, and performed the data analysis and interpretation. A.W. drafted the paper, and S.A.S. provided revisions. S.A.S. was the PI on the project. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

References

- Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Rössler W. Melancholia and atypical depression in the Zurich study: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, course, comorbidity and personality. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H, Parker G. Meta-review of depressive subtyping models. Journal of affective disorders. 2012;139:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MP, Nitsch AM, Miltner WH, Straube T. A single-trial estimation of the feedback-related negativity and its relation to BOLD responses in a time-estimation task. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:3005–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3684-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bench C, Frackowiak R, Dolan R. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow on recovery from depression. Psychological medicine. 1995;25:247–261. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R, Santesso D, Fagerness J, Perlis R, Pizzagalli D. Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 1 (CRHR1) genetic variation and stress interact to influence reward learning. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:13246–13254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2661-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress J, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein D, Hajcak G. Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress J, Smith E, Foti D, Klein D, Hajcak G. Neural response to reward and depressive symptoms in late childhood to early adolescence. Biological psychology. 2012;89:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Saxena S, Silverman DH, Fairbanks LA, Phelps ME, Huang S-C, Wu H-M, Maidment K, Baxter LR, Alborzian S. Brain metabolic changes in major depressive disorder from pre-to post-treatment with paroxetine. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 1999;91:127–139. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo P, Barlow DH, DiNardo PA. Anxiety disorders interview schedule adult version (ADIS-IV) Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Browning M, Holmes EA, Charles M, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Using attentional bias modification as a cognitive vaccine against depression. Biological psychiatry. 2012;72:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J, Foti D, Mujica-Parodi L, Harmon-Jones E, Hajcak G. Ventral striatal and medial prefrontal BOLD activation is correlated with reward-related electrocortical activity: A combined ERP and fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;57:1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-S, Eaton WW, Gallo JJ, Nestadt G. Understanding the heterogeneity of depression through the triad of symptoms, course and risk factors: a longitudinal, population-based study. Journal of affective disorders. 2000;59:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert B. The RDoC framework: facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:28–35. doi: 10.1002/wps.20087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert B, Insel T. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC medicine. 2013;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CV, Rush AJ, Harris AW, Boyce PM, Rekshan W, Etkin A, DeBattista C, Schatzberg AF, Arnow BA, Williams LM. Impairment and distress patterns distinguishing the melancholic depression subtype: An iSPOT-D report. Journal of affective disorders. 2015;174:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Felder JN, Petty C, Bizzell J, Ernst M, Smoski MJ. The effects of psychotherapy on neural responses to rewards in major depression. Biological psychiatry. 2009;66:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Kozink RV, McClernon FJ, Smoski MJ. Remitted major depression is characterized by reward network hyperactivation during reward anticipation and hypoactivation during reward outcomes. Journal of affective disorders. 2012;136:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams J. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders—Research version. Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E, Christopher May J, Siegle G, Ladouceur C, Ryan N, Carter C, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Dahl R. Reward-related decision-making in pediatric major depressive disorder: an fMRI study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E, Hariri A, Martin S, Silk J, Moyles D, Fisher P, Brown S, Ryan N, Birmaher B, Axelson D. Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:64–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E, Shaw D, Dahl R. Alterations in reward-related decision making in boys with recent and future depression. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Carlson J, Sauder C, Proudfit G. Reward dysfunction in major depression: Multimodal neuroimaging evidence for refining the melancholic phenotype. NeuroImage. 2014;101:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Depression and reduced sensitivity to non-rewards versus rewards: Evidence from event-related potentials. Biological psychology. 2009;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Genetic variation in dopamine moderates neural response during reward anticipation and delivery: Evidence from event-related potentials. Psychophysiology. 2012;49:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Kotov R, Klein D, Hajcak G. Abnormal neural sensitivity to monetary gains versus losses among adolescents at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011a;39:913–924. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Weinberg A, Dien J, Hajcak G. Event-related potential activity in the basal ganglia differentiates rewards from non-rewards: Temporospatial principal components analysis and source localization of the feedback negativity. Human Brain Mapping. 2011b;32:2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Liu H, Klein D, Daughters SB, Shankman SA. Is risk-taking propensity a familial vulnerability factor for alcohol use? An examination in two independent samples. Journal of psychiatric research. 2015;68:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hamilton JP, Cooney RE, Singh MK, Henry ML, Joormann J. Neural processing of reward and loss in girls at risk for major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:380–387. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Foland-Ross LC. Understanding Familial Risk for Depression A 25-Year Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2014;9:94–108. doi: 10.1177/1745691613513469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles M, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55:468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Choate VR, Detloff A, Benson B, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration during incentive anticipation in pediatric anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):205–212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Hariri AR, Williamson DE. Blunted ventral striatum development in adolescence reflects emotional neglect and predicts depressive symptoms. Biological Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Monroe SM. Childhood adversity and the endogenous versus nonendogenous distinction in women with major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:387–393. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Monroe SM. Severe melancholic depression is more vulnerable than nonmelancholic depression to minor precipitating life events. Journal of affective disorders. 2006;91:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Beck AT. Subtyping major depression: a taxometric analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:686. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Kraemer HC, Krueger RF. The feasibility and need for dimensional psychiatric diagnoses. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1671–1680. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600821X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition & Emotion. 2000;14:711–724. [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd C, Coles M. The neural basis of human error processing: Reinforcement learning, dopamine, and the error-related negativity. Psychological Review. 2002;109:679–709. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd C, Pakzad-Vaezi K, Krigolson O. The feedback correct-related positivity: Sensitivity of the event-related brain potential to unexpected positive feedback. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:688–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:817–823. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100061011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine D, Quinn K, Sanislow C, Wang P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RH, Jenkins LM, Gabriel LB, Barba A, Ryan KA, Weisenbach SL, Verges A, Baker AM, Peters AT, Crane NA. Increased Coupling of Intrinsic Networks in Remitted Depressed Youth Predicts Rumination and Cognitive Control. PloS one. 2014;9:e104366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell PA, Andrew C, Williams SC, Brammer MJ, Phillips ML. The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. Endogenomorphic depression: a conceptual and terminological revision. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;31:447–454. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760160005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. Classification of depressive disorders in the DSM-V: proposal for a two-dimension system. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:552. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Proudfit G, Kessel E, Dyson M, Olino T, Klein D. Neural reactivity to monetary rewards and losses in childhood: Longitudinal and concurrent associations with observed and self-reported positive emotionality. Biological psychology. 2015;104:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Proudfit G, Klein D. Neural reactivity to rewards and losses in offspring of mothers and fathers with histories of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:287. doi: 10.1037/a0036285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Rehm LP. The empirical status of melancholia: Implications for psychology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:25–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-h., Wang L.-z., Shang H.-r., Shen Y, Li Z, Cheung EF, Chan RC. The influence of anhedonia on feedback negativity in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychologia. 2014;53:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond S, Lovibond P. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. The Psychology Foundation of Australia. Inc.; Sydney: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lux V, Kendler K. Deconstructing major depression: a validation study of the DSM-IV symptomatic criteria. Psychological medicine. 2010;40:1679–1690. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Fat DM, Boerma J. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, Silva JA, Tekell JL, Martin CC, Lancaster JL. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCabe C, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Neural representation of reward in recovered depressed patients. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:667–677. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1573-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland B, Klein D. Emotional reactivity in depression: diminished responsiveness to anticipated reward but not to anticipated punishment or to nonreward or avoidance. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:117–122. doi: 10.1002/da.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMakin DL, Siegle GJ, Shirk SR. Positive Affect Stimulation and Sustainment (PASS) module for depressed mood: A preliminary investigation of treatment-related effects. Cognitive therapy and research. 2011;35:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9311-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melartin T, Leskela U, Rytsala H, Sokero P, Lestela-Mielonen P, Isometsa E. Comorbidity and stability of melancholic features in DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Psychological medicine. 2004;34(08):1443–1452. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner W, Braun C, Coles M. Event-related brain potentials following incorrect feedback in a time-estimation task: Evidence for a “generic” neural system for error detection. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9:788–798. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris BH, Rottenberg J. Heightened reward learning under stress in generalized anxiety disorder: A predictor of depression resistance? Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015;124(1):115–127. doi: 10.1037/a0036934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, McGowan S, Sarapas C, Robison-Andew E, Altman S, Campbell M, Gorka S, Katz A, Shankman S. Biomarkers of threat and reward sensitivity demonstrate unique associations with risk for psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:662. doi: 10.1037/a0033982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino T, McMakin D, Dahl R, Ryan N, Silk J, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Forbes E. “I won, but I'm not getting my hopes up”: Depression moderates the relationship of outcomes and reward anticipation. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2011;194:393–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Barrera A, Ellis SP, Li S, Burke AK, Grunebaum M, Endicott J, Mann JJ. Instability of symptoms in recurrent major depression: a prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:255–261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Defining melancholia: the primacy of psychomotor disturbance. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Austin M, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, Boyce P, Eyers K. Sub-typing depression, I. Is psychomotor disturbance necessary and sufficient to the definition of melancholia? Psychological medicine. 1995;25:815–823. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvaz MA, Maloney T, Moeller SJ, Woicik PA, Alia-Klein N, Telang F, Goldstein RZ. Sensitivity to monetary reward is most severely compromised in recently abstaining cocaine addicted individuals: a cross-sectional ERP study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2012;203(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechtel P, Dutra S, Goetz E, Pizzagalli D. Blunted reward responsiveness in remitted depression. Journal of psychiatric research. 2013;47:1864–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli D, Holmes A, Dillon D, Goetz E, Birk J, Bogdan R, Dougherty D, Iosifescu D, Rauch S, Fava M. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:702. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli D, Jahn A, O’Shea J. Toward an objective characterization of an anhedonic phenotype: a signal-detection approach. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli D, Oakes T, Fox A, Chung M, Larson C, Abercrombie H, Schaefer S, Benca R, Davidson R. Functional but not structural subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in melancholia. Molecular psychiatry. 2004;9:393–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfit GH. The reward positivity: From basic research on reward to a biomarker for depression. Psychophysiology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/psyp.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal A, Collishaw S, Thapar A, Rice F. ‘The risks of playing it safe’: a prospective longitudinal study of response to reward in the adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:27–38. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick J, Little A, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Romens S, Casement M, McAloon R, Keenan K, Hipwell A, Guyer A, Forbes E. Adolescent girls’ neural response to reward mediates the relation between childhood financial disadvantage and depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso D, Steele K, Bogdan R, Holmes A, Deveney C, Meites T, Pizzagalli D. Enhanced negative feedback responses in remitted depression. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1045. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283036e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Romo R, Ljungberg T, Mirenowicz J, Hollerman J, Dickinson A. Reward-related signals carried by dopamine neurons. In: Houk J, Davis J, Beiser D, editors. Models of information processing in the basal ganglia. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shankman S, Gorka S. Psychopathology research in the RDoC era: Unanswered questions and the importance of the psychophysiological unit of analysis. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman S, Klein D, Tenke C, Bruder G. Reward sensitivity in depression: A biobehavioral study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:95. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman S, Nelson B, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew E, Campbell M, Altman S, McGowan S, Katz A, Gorka S. A psychophysiological investigation of threat and reward sensitivity in individuals with panic disorder and/or major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:322. doi: 10.1037/a0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman S, Sarapas C, Klein D. The effect of pre-vs. post-reward attainment on EEG asymmetry in melancholic depression. International journal of psychophysiology. 2011;79:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele J, Kumar P, Ebmeier KP. Blunted response to feedback information in depressive illness. Brain. 2007;130:2367–2374. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubl B, Kuehner C, Kirsch P, Ruttorf M, Flor H, Diener C. Neural reward processing in individuals remitted from major depression. Psychological medicine. 2015;45(16):3549–3558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker J, Dillon D, Pizzagalli D. The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. Neuroimage. 2009;46:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O'Hara M, Simms L, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez E, Gamez W, Stuart S. Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:253. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara M, Naragon-Gainey K, Koffel E, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Stasik S, Ruggero C. Development and validation of new anxiety and bipolar symptom scales for an expanded version of the IDAS (the IDAS-II) Assessment. 2012;19:399–420. doi: 10.1177/1073191112449857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Liu H, Hajcak G, Shankman S. Blunted Neural Response to Rewards as a Vulnerability Factor for Depression: Results from a Family Study. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/abn0000081. Publication in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Liu H, Shankman S. Blunted neural response to errors as a trait marker of melancholic depression. 2015. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weinberg A, Luhmann C, Bress J, Hajcak G. Better late than never? The effect of feedback delay on ERP indices of reward processing. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;12:671–677. doi: 10.3758/s13415-012-0104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR* D-child report. Jama. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton AE, Kakani P, Foti D, Van’t Veer A, Haile A, Crowley DJ, Pizzagalli DA. Blunted Neural Responses to Reward in Remitted Major Depression: A High-Density Event-Related Potential Study. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2016;1(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]