Abstract

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive pediatric tumor affecting growing bones that typically occurs in adolescents and young adults. Although advances in treatment have been made in recent years, a high proportion of patients relapse due to metastases, which are frequently resistant to chemotherapy and pose a significant threat to long-term survival. Previous studies have demonstrated that the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is associated with cancer occurrence and metastasis, and our previous study demonstrated the occurrence of EMT in osteosarcoma. Notch is a regulator involved in several cellular processes, and previous studies have identified that the Notch signaling pathway may be activated during chemotherapy. However, whether chemotherapy affects the EMT remains to be elucidated. To address this issue, in the present study osteosarcoma cells were exposed to sublethal doses of doxorubicin, which resulted in upregulation of the expression of genes in the Notch signaling pathway and its target genes. Furthermore, doxorubicin treatment promoted mesenchymal-like properties and enhanced the migration and invasion of cells. In addition, treatment with the selective γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT was able to prevent the EMT and inhibit the in vitro migration of osteosarcoma cells. The results of this study suggested that there is a significant correlation between the Notch signaling pathway and the EMT, and revealed an underlying molecular mechanism by which doxorubicin may induce the EMT via Notch signaling.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, doxorubicin, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Notch

Introduction

Osteosarcoma, which is the most common malignant mesenchymal tumor of the bone, commonly occurs in the extremities of adolescents and young adults (1). Advances in neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical techniques have improved survival rates for this form of cancer; however, drug resistance and distant metastases remain a significant challenge for patients and clinicians (2).

Although numerous molecular markers have been associated with the metastasis of human carcinomas, the loss of epithelial differentiation is considered an important feature contributing to malignancy. This phenomenon manifests as the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The EMT is essential for a series of biological processes, including implantation, organ development and embryogenesis, as well as being involved in organ fibrosis and tissue regeneration (3). Previous studies have revealed that the EMT is associated with cancer occurrence and metastasis, promoting the conversion of early-stage tumors into invasive malignancies. During the process of the EMT, the epithelial-specific junction protein, epithelial-cadherin (E-cadherin), is downregulated and mesenchymal proteins, including neural-cadherin (N-cadherin), are upregulated (4). Consequently, epithelial cells transform into individual, non-polarized, motile and invasive mesenchymal cells, which exhibit increased metastasis and invasion (5).

Previous studies have suggested that the EMT, metastasis and chemoresistance are associated with tumor progression (6,7). Our previous study demonstrated that the EMT occurs in osteosarcoma (8). Doxorubicin is extensively used as a chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of various solid tumors, and has been reported to induce the EMT in human gastric and colon cancers (9,10). However, the association between doxorubicin and the EMT in human osteosarcoma cells remains to be established. The EMT is closely associated with the interaction of extracellular signals, as well as a number of secreted cytokines. Notch signaling regulates a series of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis and angiogenesis (11). In addition, the Notch signaling pathway has been reported to be upregulated in a number of human malignancies (12). Previous studies have demonstrated that the Notch signaling pathway is involved in the process of EMT (13).

Furthermore, our previous experiment revealed that a low dose of doxorubicin activates the Notch signaling pathway, influencing the proliferation and migration of osteosarcoma cell lines (14); however, the role of Notch signaling in the EMT processes of osteosarcoma remain to be elucidated. Therefore, the focus of the present study was to investigate the function of the Notch signaling pathway in the EMT at a low concentration of doxorubicin.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

RPMI-1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The lentiviral transcriptional reporter vector, pGreenFire1-Notch-EF1-Puro, was purchased from System Biosciences (#121010-003; Palo Alto, CA, USA). The primary antibodies and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA USA), which included anti-Notch1 (#ab20687; dilution, 1:1,000), anti-hairy and enhancer of split-1 (Hes-1) (#ab194111; dilution, 1:1,000), anti-vimentin (#ab5741; dilution, 1:1,000) anti-E-cadherin (#ab17021; dilution, 1:1,000), anti-N-cadherin (#ab20191; dilution, 1:1,000) and anti-β-actin (#ab8226; dilution, 1:2,000) antibodies.

Cell culture

The human osteosarcoma cell lines 143B-TK and U2OS were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (Wuhan, China). 143B-TK cells were cultured in α-minimum essential medium Eagle (α-MEM; HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) and U2OS cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with 10% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin, incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere, and harvested upon reaching ~80% confluency.

Lentiviral-reporter vector construction and infection

The Notch promoter region (8.6 kb) was cloned into the multiple cloning site of the lentiviral vector, pGreenFire1-Notch-EF1-Puro. HEK293T cells (China Center for Type Culture Collection) were transfected with the constructs and then the viral supernatants were obtained. 143B-TK and U2OS cells were infected with the viral supernatant and selected using puromycin (10 µg/ml) for one week to obtain stable reporter cells. The HEK293T, 143B-TK and U2OS cells used for viral construction and infection were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium without FBS. The transfection reagent polybrene were purchased from System Biosciences. The temperature of transfection was 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere; the cells were continuously cultured for 72 h following transfection. Cells were also transfected with a mouse cytomegalovirus (m-CMV) construct as a negative control and pGreenFire1-CMV (#TR000PA-1) as a positive control (both System Biosciences).

Drug treatment

The stable CXLIIIB-TK and U2OS reporter cells were divided into four groups, as follows: The control group (cultured without any drugs); the doxorubicin-treated group; the doxorubicin + DAPT group; and the doxorubicin + dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) group. The cells were treated separately with 50 nmol/l doxorubicin, 50 nmol/l DAPT (a selective γ-secretase inhibitor; #S2215; Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), or an equal volume of PBS or DMSO for the controls for 7 days. The medium was changed every alternate day, with the addition of the same dosage of doxorubicin each time, prior to performance of the reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), western blot analysis, wound healing assay and Transwell assay.

Flow cytometry

The 143B-TK and U2OS stable reporter cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin solution, then resuspended and washed in PBS. The cells were maintained on ice prior to analysis. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was assessed using flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and analyzed using BD CellQuestTM™ Pro software (version 5.1; BD Biosciences).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (#15596-026; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (#K1622; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). qPCR was then performed using an ABI 7900 System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in the presence of SYBR green using FastStart Universal SYBR-Green Master (Rox) (#04913914001; Roche Applied Science Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The gene-specific primers are listed in Table I. Target sequences were amplified at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. β-actin was used as an endogenous normalization control. All assays were performed in triplicate. The fold change in mRNA expression was determined according to the 2−∆∆Cq method (15).

Table I.

Primer sequences used for qPCR.

| Gene | Primer sequences used for qPCR, 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| Notch 1 | |

| Forward | CCGACGCACAAGGTGTCTTC |

| Reverse | CGTTCTTCAGGAGCACAACTG |

| Hes-1 | |

| Forward | CAGATCAATGCCATGACCTACC |

| Reverse | AGCCTCCAAACACCTTAGCC |

| GAPDH | |

| Forward | ACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCAT |

| Reverse | GTTTTTCTAGACGGCAGGTCAGG |

Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were extracted using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid method (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Cell lysates containing 40 µg protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; #abs49001012a; Absin Bioscience, Inc., Shanghai, China) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibodies diluted in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk powder in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with Tween-20 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The membranes were washed with PBS and incubated with a rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (#BA1054; dilution, 1:5,000; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed again with PBS and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore). The software used to quantify the band intensities was Image J 1.48u (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Wound healing assay

In total, 5×105 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere to attach. When adherent cells reached ~90% confluency, a scratch was made using a 200-µl pipette tip. The cells were washed three times with PBS and further incubated in medium without FBS for 24 h. The 143B-TK cells were cultured in α-MEM and the U2OS cells were cultured in DMEM. The migration was observed and recorded under a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Transwell assay

Matrigel-coated Transwell invasion assay plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) were used for this assay. Assayed cells were placed in the upper chamber (1×104 cells/well) in RPMI-1640 medium without FBS. The lower chambers were filled with α-MEM/DMEM medium with 10% FBS. After culturing for 24 h at 37°C, the inserts were removed and the inner side was wiped with cotton swabs. The filters were stained with Harris hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore) for 20 min and peeled off following washing three times with PBS. The migrated cells were counted under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U; Nikon Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed independently ≥2 times and the results were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed Student's t-test was used to estimate intergroup differences if not otherwise stated. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

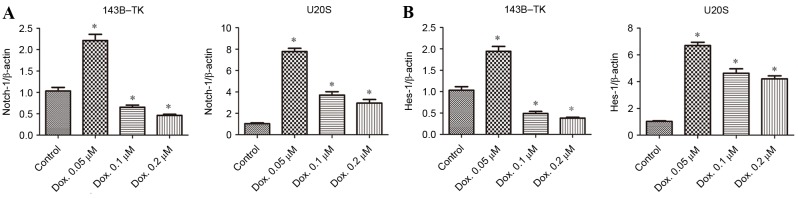

Doxorubicin treatment results in the upregulation of Notch signaling pathway gene expression and its target genes

To examine the expression of Notch signaling and its downstream genes in human osteosarcoma cell lines under doxorubicin treatment, the commonly used 143B-TK and U2OS osteosarcoma cell lines were analyzed in the current study. The cells were treated with 0.05, 0.1 or 0.2 µM doxorubicin for 1 week. The expression of Notch1 and its target genes, including Hes1, were analyzed using RT-qPCR. The results revealed that Notch1 and Hes1 expression altered in a dose-dependent manner in the two cell lines. The trend of increasing Notch signaling was negatively correlated with drug concentration, particularly when the cells were treated at the concentration of 0.05 µM. The 143B-TK and U2OS cell lines exhibited a significant elevation in the expression of Notch1 (Fig. 1A) and Hes-1 (Fig. 1B) following treatment with 0.05 µM doxorubicin, and by ~2-fold in 143B-TK cells and ~7-fold in U2OS cells, as compared with the control group (all P<0.05). However, Notch1 expression levels significantly decreased with an increase in drug concentration compared with the control (all P<0.05), so the concentration of 0.05 µM was selected.

Figure 1.

Altered expression of Notch1 and its target genes upon treatment with Dox. Three different concentrations of Dox (0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 µM) were used to treat 143B-TK and U2OS cell lines for 1 week, and the mRNA expression levels of (A) Notch-1 and (B) Hes-1 were subsequently evaluated by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05, vs. the control group. Dox, doxorubicin; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1.

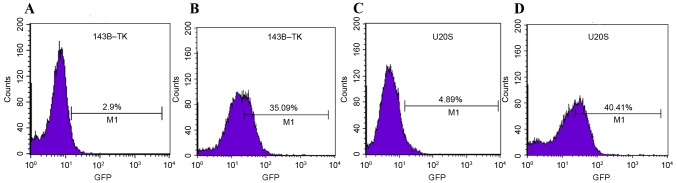

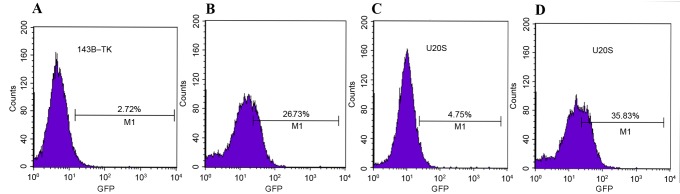

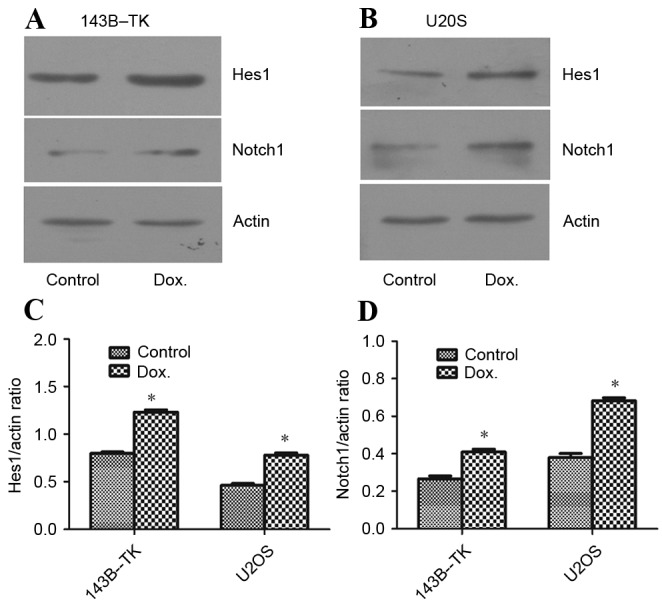

Conversely, no significant differences in Hes5 and Hey1 were observed among the various drug concentrations in the two cell lines (data not shown). According to the significantly altered Notch1 expression in the two cell lines, 0.05 µM of doxorubicin was selected as the treatment concentration for subsequent experiments. Similar to the aforementioned results, Notch1 and Hes1 proteins in 143B-TK and U2OS cells were increased at the selected concentration of drug-treatment (Fig. 2A-D). Furthermore, 0.05 µM doxorubicin was added to stable Notch-reporter cells for 1 week and the intensity of the fluorescent signal was detected in treated or untreated of cells by flow cytometry. The results revealed that treatment of the 143B-TK and U2OS cell lines with a low concentration of doxorubicin (0.05 µM) significantly increased Notch expression by ~10-fold (P=0.0148 and P=0.0224, respectively), as compared with the untreated cells (Fig. 3A-D).

Figure 2.

Protein expression of Notch1 and Hes-1 was upregulated in 143B-TK and U2OS osteosarcoma cell lines by treatment with 0.05 µM Dox. The protein expression of Notch and Hes-1 in (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells lines was analyzed by western blotting. The protein expression levels of (C) Hes-1 and (D) Notch1 were shown to be significantly upregulated for the cells treated with a low concentration of Dox. *P<0.05 vs. the control group. Dox, doxorubicin; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence of the stable reporter cells osteosarcoma cell lines was detected by flow cytometry. The results revealed that the intensity of fluorescence was elevated from (A) 2.9% in the control group to (B) 35.09% in the Dox group for 143B-TK cells and (C) 4.89% in the control group to (D) 40.41% in the Dox group for U2OS cells. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

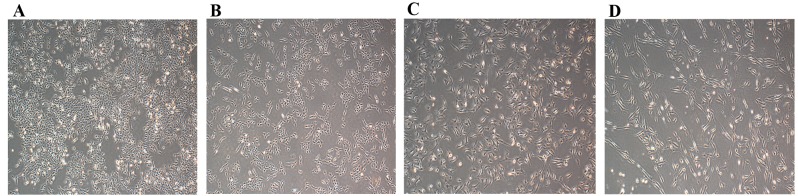

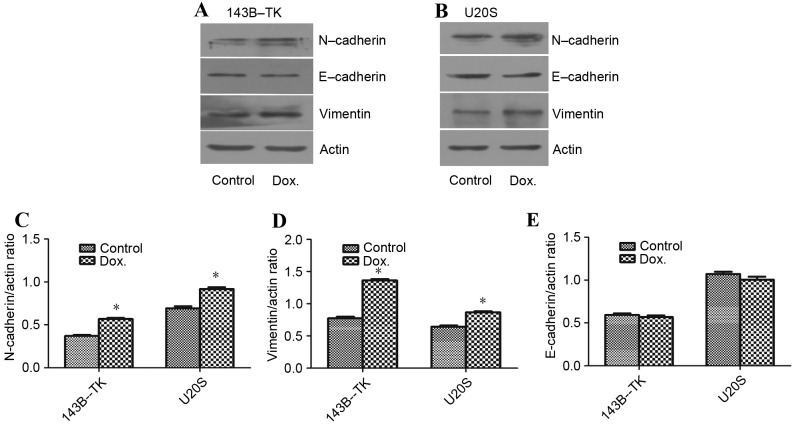

Doxorubicin treatment promotes mesenchymal-associated properties in osteosarcoma

The EMT process is regulated by developmental transcriptional factors, which induce the expression of mesenchymal markers, but repress epithelial marker expression. In addition, EMT is often accompanied by the alteration from a morphologically rounded shape to a spindle shape (3). In the current study, 143B-TK and U2OS cells were treated with 0.05 µM doxorubicin for 1 week. The doxorubicin-treated cells showed marked changes in cell morphology, appearing elongated, with a greater number of branches arising from the cell periphery, as compared with the control cells (Fig. 4A-D). In addition, the expression levels of mesenchymal markers, including vimentin and N-cadherin, as well as the epithelial marker E-cadherin, were examined in 143B-TK and U2OS cells in the presence or absence of 0.05 µM doxorubicin. The results of the western blot analysis revealed that the protein levels of N-cadherin (P=0.0245 and P=0.0467 in 143B-TK and U2OS cells, respectively) and vimentin (P=0.0351 and P=0.0458 in 143B-TK and U2OS cells, respectively) were significantly upregulated in the doxorubicin-treated group compared with the control, whereas the epithelial marker E-cadherin exhibited no detectable difference between the treated and control groups (Fig. 5A-E).

Figure 4.

Osteosarcoma cells exhibit mesenchymal morphological characteristics following treatment with Dox. The morphology of normal (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells was spindle-shaped. Following treatment with Dox for 1 week, the (C) 143B-TK and (D) U2OS cells were elongated, and more branches arose from the cell periphery. Dox, doxorubicin.

Figure 5.

Dox treatment promotes mesenchymal-associated properties in osteosarcoma cells. The expression of the mesenchymal markers vimentin, N-cadherin and E-cadherin was detected in (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells by western blotting. (C) N-cadherin and (D) Vimentin expression levels were increased significantly upon treatment with 0.05 µM Dox, whereas (E) E-cadherin expression levels were decreased under this condition. *P<0.05 vs. the control group. N-cadherin, neural-cadherin; E-cadherin, epithelial-cadherin; Dox, doxorubicin.

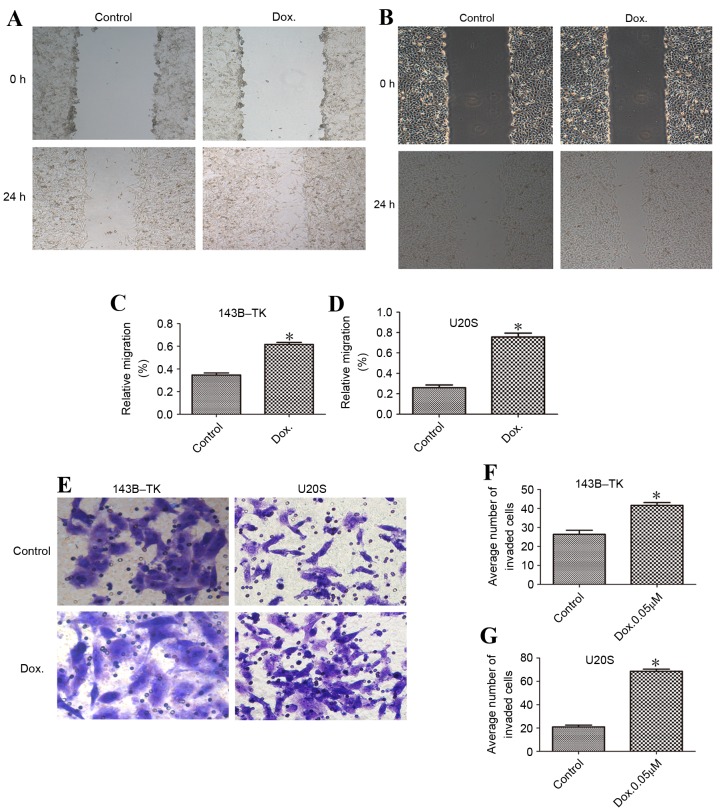

Doxorubicin-treated cells are prone to migration and invasion

To investigate the migratory and invasive capacity of osteosarcoma cell lines, wound healing and Transwell assays were performed in the presence or absence of doxorubicin treatment. According to the results of the wound healing assay, the doxorubicin-treated cells of the two cell lines exhibited significantly increased cell migration compared with the control group (Fig. 6A-D). The invasive potential through the Matrigel in the doxorubicin-treated group was also enhanced, with an average increase of 2.51±0.53-fold (Fig. 6E-G), demonstrating that treatment with doxorubicin is associated with increased cell motility.

Figure 6.

Dox promotes the migratory and invasive ability of osteosarcoma cells. Wound healing assays were performed to assess the migration of (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells. The relative migration of (C) 143B-TK and (D) U2OS cells was promoted by treatment with low concentrations of Dox. (E) Transwell assays were used to assess the invasion of the osteosarcoma cells. The numbers of invaded (F) 143B-TK and (G) U2OS cells were significantly increased following treatment with Dox, as compared with the control cells. *P<0.05 vs. the control group. Dox, doxorubicin.

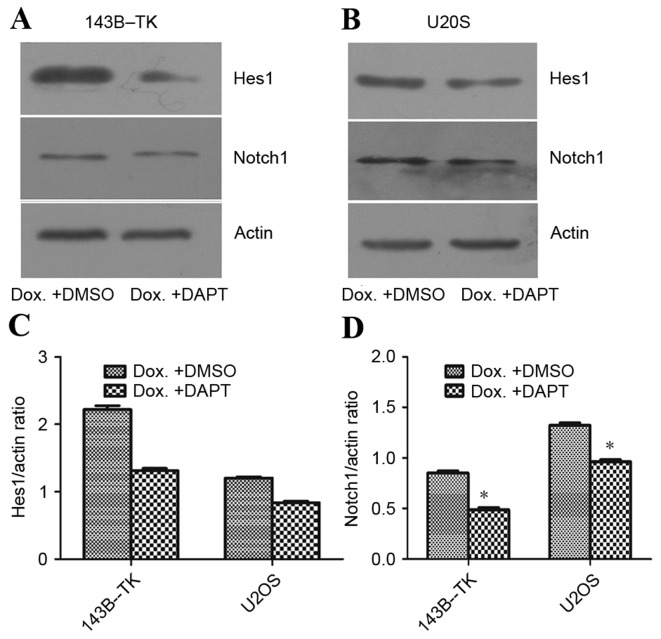

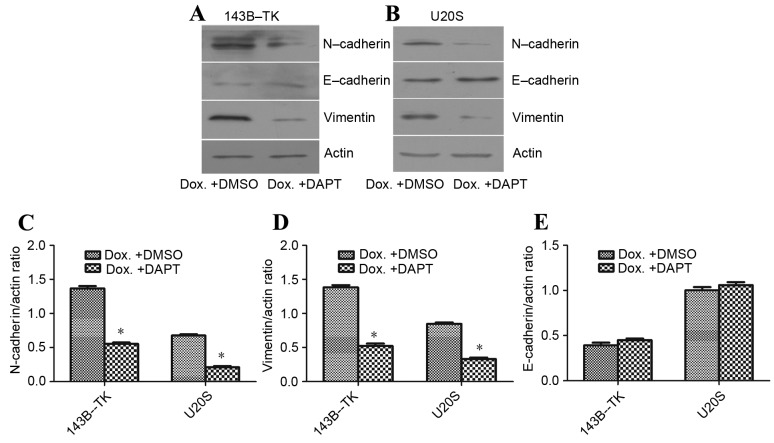

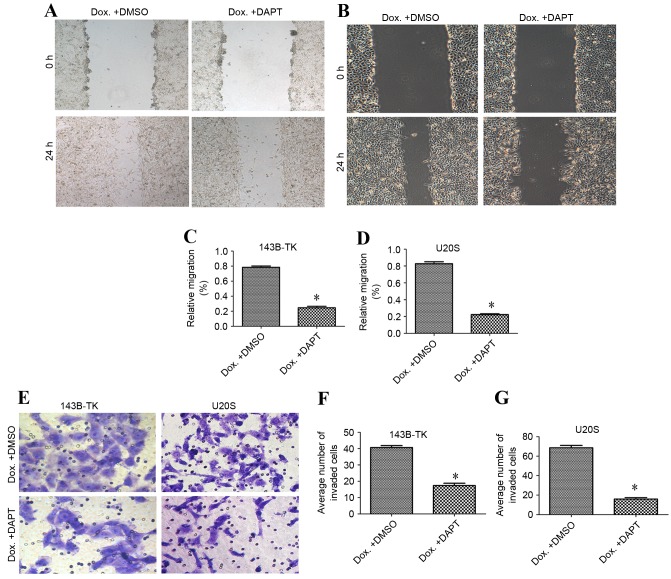

Notch signaling inhibitor may prevent the EMT and suppress the motility of osteosarcoma cell lines

To examine the role of the Notch signaling pathway in the progress of EMT that is induced by doxorubicin, the 143B-TK and U2OS osteosarcoma cells that had been treated with a low concentration of doxorubicin were treated with DAPT or DMSO. The results of the qPCR and western blot analysis revealed that DAPT treatment markedly suppressed the expression of the Notch1 downstream target Hes5, as compared with the DMSO group (Fig. 7A-D). Furthermore, the fluorescent signal upregulated by doxorubicin exhibited a significant decrease; 2.72 and 4.75% of cells exhibited fluorescence in the DAPT group, compared with 26.73 and 35.83% of cells in the DMSO group, for 143B-TK and U2OS cell lines, respectively (Fig. 8A-D). To further examine the underlying molecular mechanisms of the γ-secretase inhibitors on the EMT in human osteosarcoma cell lines, the expression of mesenchymal-associated proteins, including E-cadherin, vimentin and N-cadherin, were investigated in 143B-TK and U2OS cells in the presence of DAPT or DMSO. The results of the western blot analysis revealed that the protein levels of N-cadherin and vimentin were significantly decreased in the DAPT-treated cells, while E-cadherin expression was upregulated in the DAPT-treated cells, as compared with the cells treated with the DMSO control (Fig. 9A-E). Overall, these results indicated that the γ-secretase inhibitor impairs EMT in human osteosarcoma cell lines. In addition, the γ-secretase inhibitor also exerted an effect of inhibition of migration (Fig. 10A-D) and invasion of osteosarcoma cells (Fig. 10E-G).

Figure 7.

DAPT represses the effects of Dox on the protein expression levels of Notch1 and Hes-1 in osteosarcoma cells. (A) The protein expression of Notch1 and Hes-1 in (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS osteosarcoma cell lines following treatment with Dox + DAPT was analyzed by western blotting. DAPT repressed the Dox-mediated increase in the expression levels of (C) Hes-1 and (D) Notch-1 and were increased upon treatment of 0.05 µM doxorubicin compared with control 143B-TK cells. *P<0.05 vs. the control group. Dox, doxorubicin; Hes-1, hairy and enhancer of split-1.

Figure 8.

Expression levels of Notch signals were altered under various treatment conditions. The expression of Notch signal in 143B-TK cells was significantly decreased to (A) 2.72% in the group treated with γ-secretase inhibitor (Dox + DAPT), as compared with (B) the group treated with Dox + DMSO, in which the fluorescence was maintained at 26.73%. The fluorescence of the Notch signal in U2OS cells was reduced to (C) 4.75% in the γ-secretase inhibitor (Dox + DAPT) group, as compared with (D) 35.83% in the group treated with Dox + DMSO. Dox, doxorubicin; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure 9.

DAPT reverses Dox-induced alterations in the protein expression levels of mesenchymal markers. The protein expression of Vimentin, N-cadherin and E-cadherin in (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells was analyzed by western blotting. The expression levels of (C) N-cadherin and (D) vimentin were decreased, and those of (E) E-cadherin were increased, in Dox + DAPT cells, as compared with Dox + DMSO cells. *P<0.05 vs. the Dox + DMSO group. N-cadherin, neural-cadherin; E-cadherin, epithelial-cadherin; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Dox, doxorubicin.

Figure 10.

A Notch signaling inhibitor was able to reduce the motility of osteosarcoma cell lines following treatment with Dox. The γ-secretase inhibitor exerted an inhibitory effect on the migration of (A) 143B-TK and (B) U2OS cells. The relative migration of the (C) 143B-TK and (D) U2OS cell lines following treatment with Dox was inhibited by DAPT, as compared with the DMSO-treated cells. (E) DAPT inhibited the invasion of osteosarcoma cells. The number of invaded cells in the Dox + DAPT group was significantly decreased in (F) 143B-TK and (G) U2OS cells, as compared with the Dox + DMSO cells. *P<0.05 vs. the Dox + DMSO group. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Dox, doxorubicin.

Discussion

The value of chemotherapy for the treatment of osteosarcoma has been demonstrated during clinical trials (16). Neoadjuvant or induction chemotherapy is typically administered to suppress the development of cancer and improve patient survival (17,18). As a widely-used chemotherapy drug, doxorubicin functions by interfering with nucleoside metabolism, leading to cytotoxicity and cell death (19). However, a significant difficulty associated with doxorubicin treatment is the development of chemoresistance. An improved understanding of the underlying mechanism by which resistance develops, and the molecular alterations that are associated with this process, may result in the development of novel therapeutic strategies in order to overcome chemoresistance. Previous studies have revealed that cancer cells exposed to chemotherapeutic drugs undergo the EMT, leading to phenotypic changes, multidrug resistance and enhanced invasive abilities (9,10,20); however, the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated. In the current study, the 143B-TK and U2OS human osteosarcoma cell lines were used to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying doxorubicin resistance and the associated cellular behaviors.

Previous studies have reported that Notch receptors and their target genes are upregulated in cervical, lung, colon, head and neck, and renal carcinomas, as well as pancreatic cancer (21,22). In our previous study, it was demonstrated that the cytostatic dose of doxorubicin activated the Notch signaling pathway (14), and the results of the present study demonstrated that doxorubicin upregulates Notch1 and its target genes. In addition, this effect occurred in a dose-dependent manner within the examined range of concentrations. A low dose of doxorubicin was selected for the experiments in the current study, and a γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT), which prevents the cleavage of the Notch receptor and blocks the Notch signaling pathway (22), was able to exert a marked inhibitory effect.

The present study also demonstrated that 143B-TK and U2OS cells underwent alterations associated with the EMT following transient doxorubicin treatment. This was indicated by changes in the expression levels of molecular markers and proteins, including decreased expression of E-cadherin, and increased levels of Vimentin and N-cadherin, as revealed using western blot analysis. In addition, the increase in the migration and invasion of 143B-TK cells corresponded with the doxorubicin-induced upregulation of Notch expression. Inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway using DAPT significantly decreased the migration and invasion of the 143B-TK cell line. The underlying mechanism by which 143B-TK and U2OS cell migration and invasion is impaired through the inhibition of Notch signaling may be via the downregulation of E-cadherin expression during the acquisition of the EMT phenotype, which reduces cell-cell adhesion and destabilizes the epithelial architecture (13). In addition, it has been reported that the overexpression of Notch-1 induces Snail expression, which attenuates E-cadherin expression and the acquisition of the EMT phenotype (23). Therefore, the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT is able to inhibit the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that transient treatment with a low concentration of doxorubicin initiated the EMT and enhanced the in vitro migration ability of osteosarcoma cells. Furthermore, it was inferred that this process may require the activation of the Notch signaling pathway, as repression of Notch1 using DAPT, a selective γ-secretase inhibitor, was able to effectively arrest the doxorubicin-induced EMT process.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff in the Central Laboratory of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China). This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81341078).

References

- 1.Savage SA, Mirabello L. Using epidemiology and genomics to understand osteosarcoma etiology. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:548151. doi: 10.1155/2011/548151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004 Data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2009;115:1531–1543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Liu L, Wang Y, Zhao G, Xie R, Liu C, Xiao X, Wu K, Nie Y, Zhang H, Fan D. KLF8 involves in TGF-beta-induced EMT and promotes invasion and migration in gastric cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1033–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano CE, Motoo Y, Iovanna JL. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. ScientificWorld Journal. 2010;10:1947–1957. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastid J. EMT in carcinoma progression and dissemination: Facts, unanswered questions, and clinical considerations. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosanò L, Cianfrocca R, Spinella F, Di Castro V, Nicotra MR, Lucidi A, Ferrandina G, Natali PG, Bagnato A. Acquisition of chemoresistance and EMT phenotype is linked with activation of the endothelin A receptor pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2350–2360. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Liu S, Guo W, Zhang C, Zhang B, Yan H, Wu Z. hTERT promoter activity identifies osteosarcoma cells with increased EMT characteristics. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:239–244. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han RF, Ji X, Dong XG, Xiao RJ, Liu YP, Xiong J, Zhang QP. An epigenetic mechanism underlying doxorubicin induced emt in the human bgc-823 gastric cancer cell. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:4271–4274. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.10.4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Liu H, Yu J, Yu H. Chemoresistance to doxorubicin induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via upregulation of transforming growth factor β signaling in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:192–198. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim TH, Shivdasani RA. Notch signaling in stomach epithelial stem cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:677–688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penton AL, Leonard LD, Spinner NB. Notch signaling in human development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, Sarkar FH. The role of Notch signaling pathway in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during development and tumor aggressiveness. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:745–751. doi: 10.2174/138945010791170860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mei H, Yu L, Ji P, Yang J, Fang S, Guo W, Liu Y, Chen X. Doxorubicin activates the Notch signaling pathway in osteosarcoma. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2905–2909. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakamoto A, Iwamoto Y. Current status and perspectives regarding the treatment of osteo-sarcoma: Chemotherapy. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2008;3:228–231. doi: 10.2174/157488708785700267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janeway KA, Grier HE. Sequelae of osteosarcoma medical therapy: A review of rare acute toxicities and late effects. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:670–678. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers PA. Muramyl tripeptide (mifamurtide) for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1035–1049. doi: 10.1586/era.09.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arafa el-SA, Zhu Q, Shah ZI, Wani G, Barakat BM, Racoma I, El-Mahdy MA, Wani AA. Thymoquinone up-regulates PTEN expression and induces apoptosis in doxorubicin-resistant human breast cancer cells. Mutat Res. 2011;706:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheel C, Eaton EN, Li SH, Chaffer CL, Reinhardt F, Kah KJ, Bell G, Guo W, Rubin J, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Paracrine and autocrine signals induce and maintain mesenchymal and stem cell states in the breast. Cell. 2011;145:926–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miele L, Miao H, Nickoloff BJ. NOTCH signaling as a novel cancer therapeutic target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:313–323. doi: 10.2174/156800906777441771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Banerjee S, Li Y, Rahman KM, Zhang Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of notch-1 inhibits invasion by inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2778–2784. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saad S, Stanners SR, Yong R, Tang O, Pollock CA. Notch mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transformation is associated with increased expression of the Snail transcription factor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1115–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]