Abstract

Re-education of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward antitumor effectors may be a promising therapeutic strategy for the successful treatment of cancer. HangAmDan-B (HAD-B), a herbal formula, has been used for stimulating immune function and activation of vital energy to cancer patients in traditional Korean Medicine. Previous studies have reported the anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic effects of HAD-B; however, evidence on the immunomodulatory action of HAD-B was not demonstrated. In the present study, immunocompetent mice were used to demonstrate the suppression of the in vivo growth of allograft Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells, by HAD-B. In addition, HAD-B inhibited the in vitro growth of LLC cells by driving macrophages toward M1 polarization, but not through direct inhibition of tumor cell growth. Furthermore, culture media transfer of HAD-B-treated macrophages induced apoptosis of LLC cells. Results of the present study suggest that the antitumor effect of HAD-B may be explained by stimulating the antitumor function of macrophages. Considering the importance of re-educating TAMs in the regulation of the tumor microenvironment, the present study may confer another option for anti-cancer therapeutic strategy, using herbal medicines such as HAD-B.

Keywords: HangAmDan-B, lung cancer, macrophage, M1, apoptosis

Introduction

The intercommunication between a tumor and its microenvironment (including stromal cells and the extracellular matrix) contributes to multiple stages of cancer progression, particularly local resistance, immune-escape and metastasis (1,2). Macrophages are a major stromal component within the tumor region, termed tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), and can promote tumor progression by changing the phenotype of the tumor (3). In general, TAMs are functionally similar to alternatively activated (M2) polarization, which exerts anti-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic activities. By contrast, classically activated (M1 polarization) macrophages act as immune-stimulatory and antitumor effectors (1,4). Thus, depletion of TAMs or their re-education toward antitumor effectors is considered a promising therapeutic strategy for the successful treatment of cancer (5,6).

HangAmDan-B (HAD-B), a Korean medicinal herbal formula, consisting of eight ingredient medicinal animals and plants, has been used for the treatment of cancer patients in the clinic to stimulate immune function and activation of vital energy (7). Previous studies have reported the anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic effects of HAD-B (7,8). In addition, the suppression of γ-aminobutyric acid B receptor 1 (GABABR1) and heat shock protein 27 (HSP27) expression was demonstrated as a molecular mechanism underlying the anti-cancer effect of HAD-B (9,10). However, previous studies have not provided evidence on the immunomodulatory action of HAD-B.

The present study demonstrated that HAD-B reduced the growth of Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) in an allograft mouse model, using immunocompetent mice. The results from in vitro experiments demonstrated that the inhibition of cancer growth is mediated by regulating macrophage shape towards M1. These results suggest that the antitumor effect of HAD-B may be explained by stimulating antitumor function of macrophages.

Materials and methods

Materials

Antibodies against caspase-3 (cat. no. 9665), poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP; cat. no. 9542) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibody for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; cat. no. sc-32233) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). All chemicals and reagents, including MTT and propidium iodide (PI), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), unless otherwise indicated.

Preparation of HAD-B

HAD-B, composed of eight herbal ingredients in a crude ground power form (Table I), was obtained from the East-West Cancer Center of Dunsan Korean Hospital (Daejeon, Korea). The water extract of HAD-B was prepared as previously reported (7). Briefly, crude powder of HAD-B was extracted with 10 times (v/w) the amount of distilled water, at room temperature for 24 h. The sample was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 30 min, filtered and lyophilized. The extracted powder was dissolved in distilled water to make a concentration of 100 mg/ml, and sterilized with a 0.2 µm syringe filter. The stock solutions were stored at −80°C until use, and diluted with PBS or culture medium prior to use in the experiments.

Table I.

Composition of ingredient herbs of HangAmDan-B.

| Scientific name | Botanical name | Amount, mg |

|---|---|---|

| Panax notoginseng Burck. | Notoginseng Radix | 84 |

| Cordyceps Militaris L. | Cordyceps | 64 |

| Cremastra appendiculata (D. Don) Makino | Cremastrae Tuber | 64 |

| Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer | Ginseng Radix Alba | 64 |

| Bos taurus var. domesticus Gmelin | Bovis Calculus | 64 |

| Pteria martensii Dunker | Margarita | 64 |

| Boswellia carterii Birdwood | Olibanum | 48 |

| Commiphora myrrha Engler | Myrrh | 48 |

| Total (1 capsule) | 500 |

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (six-week-old; weight, 20–24 g) were purchased from Orient Bio Inc. (Sungnam, Korea). The animals were all housed in certified laboratory chambers, maintained at a constant temperature (22±1°C), humidity (50±5%), and 12 h dark/light cycles. The mice had free access to a standard diet and drinking water prior to the experiment. All experimental procedures followed the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health of Korea, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pusan National University, Pusan, Republic of Korea.

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells and LLC cells were provided by the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Welgene, Daegu, South Korea) supplemented with L-glutamine (200 mg/l), 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore), and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in a humidified cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) prior to experiments. The morphology of cultured RAW 264.7 cells was observed using inverted optical microscopy (magnification, ×200; Nikon ECLIPSE TS100, Tokyo, Japan).

Tumor allograft model

Separated LLC cells (5×105 cells) were suspended in 100 µl of PBS and injected into the subcutaneous dorsa of 7-week-old C57BL/6 mice. One day after the tumor cell inoculation, the mice in the control group were administered daily with 100 µl of PBS orally, for 21 days. The mice in the HAD-B-treated group were orally administrated with HAD-B (2 mg in 100 µl PBS/20 g mouse) per day, for 21 days. Tumor volumes were measured with a pair of calipers at 14, 17 and 21 days. The volumes were calculated according to the formula [(1x w2)/2], where l and w stand for length and width, respectively. At the end of the experiment, all mice were sacrificed by inhalation of CO2 gas and the tumor specimens were immediately removed and weighed.

Cell viability assay

Cytotoxic effects caused by HAD-B treatment or culture medium of HAD-B-treated RAW 264.7 cells were measured using a MTT assay. Briefly, LLC or RAW 264.7 cells were incubated in 24-well plates with indicated concentrations of HAD-B (0, 100, 500 and 1,000 µg/ml). After culture for 24 or 48 h, MTT solution (2.0 mg/ml) was added and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 4 h. The conditioned media were removed, and formazan crystals, which formed in live cells, were measured by absorbance at 540 nm, using a microplate reader (Spectramax M2; Molecular Devices, LCC., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNAs were extracted from cells using the GeneJET RNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of total RNA (2 µg) were applied for synthesizing cDNA using oligo-dT primer and AccuPower RT-PreMix (Bioneer Co., Daejeon, Korea). The cDNA was amplified by PCR with the following primers: Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) sense, 5′-AGTCCGGCAGACAATCCTTGCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCCACGCGAATGACGCTCTGG-3′; interleukin (IL)-1β sense, 5′-AGCCTGTGGATGGTGGTGTTTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-CCTTGCTTGATGACTCCCAAAAG-3′; monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) sense, 5′-TACGATGGGCACTACGAGGGAG-3′ and antisense 5′-GCAAAGAAACCAACAGGGAGACCAC-3′; tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) sense, 5′-AGTCCGGCAGACAATCCTTGCA-3′ and antisense 5′-ATCCACGCGAATGACGCTCTGG-3′; arginase-1 sense, 5′-AGTCCGGCAGACAATCCTTGCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCCACGCGAATGACGCTCTGG-3′; Ym1 sense, 5′-AGTCCGGCAGACAATCCTTGCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCCACGCGAATGACGCTCTGG-3′; CD206 sense, 5′-AGTCCGGCAGACAATCCTTGCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCCACGCGAATGACGCTCTGG-3′; GAPDH sense, 5′-GGAGCCAAAAGGGTCATCAT-3′ and antisense, 5′-GTGATGGCATGGACTGTGGT-3′. Amplification of the PCR reactions was performed with AccuPower PCR-PreMix (Bioneer Co.), under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles (for iNOS, IL-1β, MCP-1, TNF-α, arginase-1, CD206 and GAPDH) or 40 cycles (for Ym1) of denaturation for 30 sec at 95°C, annealing for 30 sec at 60°C (for iNOS, IL-1β, MCP-1, TNF-α, arginase-1, Ym1, CD206 and GAPDH) and extension for 30 sec at 72°C, with a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. The PCR products were separated in 1.5% agarose gels and images visualized under UV light were captured with GelDoc-It TS Imaging System (UVP, Inc., Upland, CA, USA).

Annexin V staining for detecting apoptosis

The same numbers of LLC cells (2×105/well) were seeded onto 24-well plates and incubated in culture medium from RAW 264.7 cells treated with the indicated concentration of HAD-B for 24 h. Apoptosis was measured using the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) apoptosis detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The control and HAD-B-treated cells (1×106) were re-suspended in 500 µl of binding buffer and incubated with 5 µl of Annexin V-FITC and 1 µl of propidium iodide (PI) solution for 15 min. The samples were then examined on a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), measuring excitation/emission at 494/525 nm for Annexin V-FITC and 535/617 nm for PI.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from cells using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The amount of protein was estimated using the Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). An equal amount (20 µg) of protein from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and the protein was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) by electrophoresis. The transferred membrane was blocked for 1 h with 5% non-fat dry milk at room temperature and incubated with anti-caspase-3 and PARP primary antibodies (both 1:200) against the target protein at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed 3 times in TBS-Tween-20) and blocked using 5% skimmed milk and incubated overnight at 4°C. The membranes were subsequently probed with goat anti-rabbit Immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. NCI1460KR; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The specific bands of proteins of interest were detected using ECL Plus (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Statistical analysis

Cell viability results were calculated by the percentage of control cells and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The differences of the mean values compared with the control groups were evaluated using two-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons, and the Student's t-test for single comparisons. The minimum level of significance was set at P<0.05 for all the analyses. All experiments were performed independently at least three times.

Results

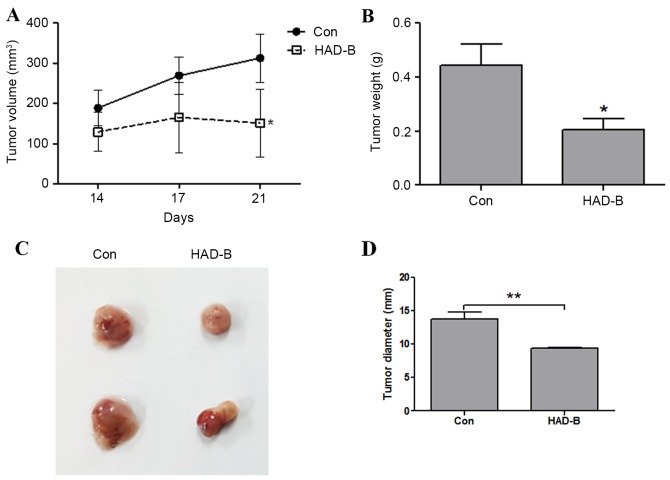

HAD-B suppressed growth of LLC cells in an in vivo allograft model

The antitumor effect of HAD-B was examined using an in vivo LLC allograft model in immunocompetent mice. The tumor volumes of allograft LLC cells measured at 14, 17 and 21 days were significantly decreased by HAD-B treatment (P<0.01). The tumor volume of control groups increased in a time-dependent manner; however, the tumor volume of HAD-B-treated groups did not show significant changes (P=0.79; Fig. 1A). The weight and size of removed tumor mass from each group was also reduced by HAD-B treatment (Fig. 1B and C). These results demonstrated that HAD-B suppressed the growth of LLC cells in the in vivo mouse model.

Figure 1.

HAD-B inhibits tumor growth in in vivo allograft mouse model using LLC cells. LLC cells (5×105 cells/100 µl PBS) were subcutaneously injected into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. HAD-B (2 mg/100 µl PBS) or carrier only were orally administrated for 21 days. (A) After 14, 17 and 21 days, the tumor size was measured using calipers and the volume was calculated. The results were shown as the mean ± SD. (B) At the end of experiment, the tumor was excised and weighed. The data were presented as the mean ± SD. (C) Images of representative tumor samples from control and HAD-B groups were shown. (D) The diameters of excised tumors were measured using calipers and the data were presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control. LLC, Lewis lung carcinoma; HAD-B, HangAmDan-B; SD, standard deviation; con, control.

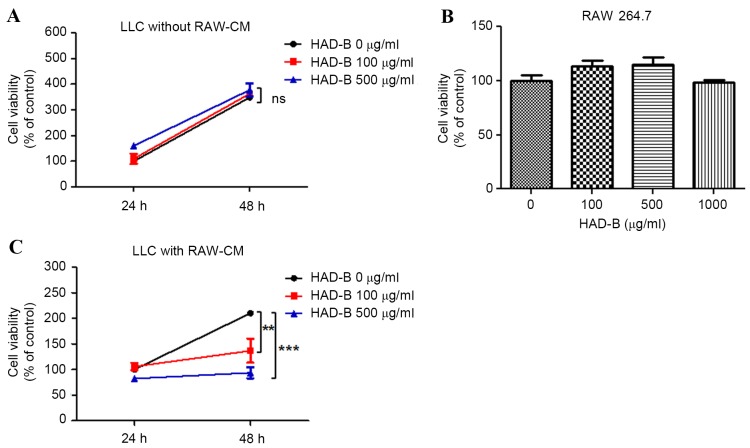

HAD-B reduced growth of LLC cells in a macrophage-dependent manner

The in vitro antitumor activity of HAD-B on LLC cells was then confirmed. However, notably, the growth of HAD-B was not suppressed by HAD-B treatment (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the in vivo antitumor effect of HAD-B involved with regulation of macrophages was examined. HAD-B had no cytotoxic effect on LLC cells up to the concentration of 1,000 µg/ml (Fig. 2B). To determine whether the antitumor effect of HAD-B is mediated by macrophages, culture media was transferred from RAW 264.7 cells to LLC cells. The growth rates of LLC cells were significantly reduced by adding the culture media from RAW 264.7 cell, treated with HAD-B in a dose-dependent manner (100 µg/ml, P<0.01; 500 µg/ml, P<0.001). At 48 h culture, following transfer of media from RAW 264.7 cells treated with 100 and 500 µg/ml, the growth of LLC cells was reduced to 65 and 44.5%, respectively, compared with the control (Fig. 2C). From these results, it is suggested that in vivo antitumor action of HAD-B may be mediated by regulation of macrophages, but is not due to the direct cytotoxic effect of HAD-B on LLC cells.

Figure 2.

HAD-B suppresses growth of LLC cells macrophage-dependent manners. (A) The LLC cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAD-B for 24 or 48 h. The viabilities of LLC cells were estimated by MTT assay. The results were calculated by percentage of control. (B) RAW 264.7 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of HAD-B for 24 h. The viabilities of RAW 264.7 cells were measured using a MTT assay and calculated as a percentage of the control. (C) RAW 264.7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAD-B for 24 h, and the culture media were transferred to LLC cells. Following incubation for 24 or 48 h, the viabilities of LLC cells were measured using a MTT assay. The results were calculated as a percentage of the control and shown as the mean ± standard deviation. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with the control. HAD-B, HangAmDan-B; LLC, Lewis lung carcinoma; SD, standard deviation; RAW-CM, culture media of RAW 264.7 cells; ns, not significant.

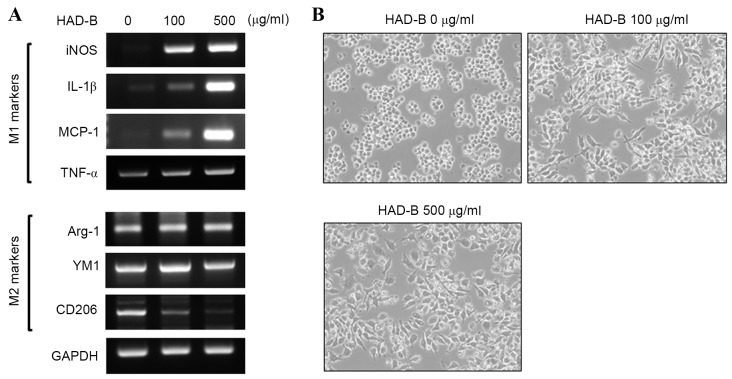

HAD-B shift macrophages phenotype toward M1

Results from RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that HAD-B increased the expression of M1 markers, including iNOS, IL-1β, MCP-1 and TNF-α, in a dose-dependent manner. By contrast, representative M2 markers, including arginase-1 and YM, were not changed by HAD-B treatment. However, the expression of CD206, a marker of alternative polarization, was reduced by HAD-B treatment (Fig. 3A). In addition, HAD-B changed the morphology of RAW 264.7 cells toward the shape of a classically activated macrophage (Fig. 3B). Results from the present study demonstrated that HAD-B drives macrophages toward a tumor-inhibitory M1 phenotype. Thus, M1 polarization of macrophages induced by HAD-B treatment may be a cause of macrophage-mediated suppression of tumor growth.

Figure 3.

HAD-B increased the expression of M1 markers of macrophages. (A) RAW 264.7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of HAD-B for 24 h. The expression of M1 and M2 markers were estimated by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis. The expression of GAPDH was used for internal control. (B) Morphological changes of RAW 264.7 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of HAD-B were observed by inverted optical microscopy (magnification; ×200). The representative images are shown. HAD-B, HangAmDan-B; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Arg-1, arginase-1; YM1, yamaha 1; CD206, cluster of differentiation 206.

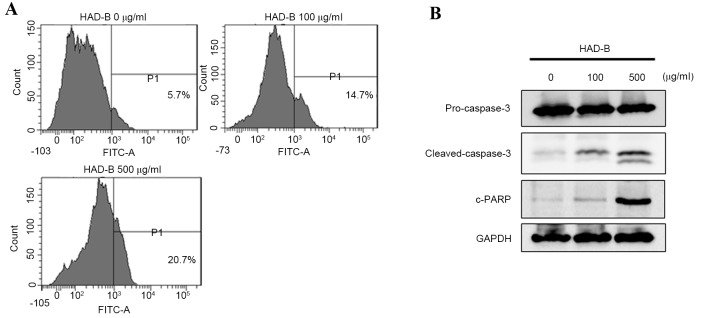

HAD-B treated macrophage culture media induces apoptosis of LLC cells

To evaluate whether macrophage-mediated death of LLC is apoptosis, FACS analysis was performed using Annexin V-FITC staining. The result demonstrated that the culture media from HAD-B treated RAW 264.7 cells induced apoptosis of LLC cells (Fig. 4A). The results showed an association between the data from the cell viability assay and changes in the macrophage phenotype. The apoptosis pathways that are activated by culture media from HAD-B-treated RAW 264.7 cells were then confirmed. The results from western blot analysis showed activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that HAD-B-treated cell culture media induce the apoptosis of LLC through a macrophage-dependent pathway.

Figure 4.

HAD-B induces apoptosis of LLC cells through soluble factors secreted by macrophages. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of HAD-B for 24 h. The cultured media were transferred to LLC cells and incubated for 24 h. (A) Apoptosis of LLC cells was detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide double-staining. (B) The activations of caspase-3 and PARP were measured by western blot analysis. HAD-B, HangAmDan-B; Lewis LLC, lung carcinoma; PARP, poly-ADP-ribose polymerase; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Discussion

Previously, antitumor effects of HAD-B were investigated in several in vitro models (7–10). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no preceding report on the in vivo antitumor effect of HAD-B. Thus, the present study examined in vivo antitumor activity of HAD-B using an immunocompetent mouse allograft model. The results from the present study demonstrated that HAD-B suppressed the growth of allograft LLC cells. However, HAD-B did not affect the growth of LLC cells in the in vitro assay. Since HAD-B has been used for stimulating immune function of cancer patients in the clinic (7), it was supposed that HAD-B may control the growth of tumor cells through the regulation of immune cells present in the tumor microenvironment. Among these immune cells, macrophages are a major cellular component within the tumor region (3). Thus, the possibility that the antitumor effect of HAD-B is mediated by macrophages was examined. When the culture media from HAD-B-treated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were transferred to LLC cells, the growth rates of LLC cells were reduced.

Macrophages polarize toward two major phenotypes: Classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2). In the majority of cancers, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) were polarized to M2 phenotype (11,12), which serve anti-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic actions (13). By contrast, M1 macrophages possess high antitumor and immune-stimulatory functions through the production of pro-inflammatory factors and the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules (14). Thus, re-education of M2-like TAMs toward a M1 phenotype is regarded as a beneficial strategy for the treatment of cancer (15,16). In the present study, HAD-B drove RAW 264.7 macrophage cells to polarize toward an antitumorigenic M1 type.

Macrophages re-educated toward M1 suppress the growth of tumor cells through diverse pathways, including secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates, promotion of Th1 response and tumoricidal activity (6,13). When culture media from THP-1-derived M1 macrophages was added to several human cancer cell lines, including HT-29 and CACO-2, the growth of tumor cells was reduced by the induction of apoptosis and retardation of cell cycles (17,18). In addition, co-culture of M1 macrophages increased the etoposide induced apoptosis in HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and A549 human lung cancer cells (19). Previous studies revealed that M1 macrophages exhibit direct cytotoxic activity on tumor cells. It is hypothesized that the direct antitumor action of M1 macrophages is mediated by soluble factors, including pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive nitrogen/oxygen intermediates (13,18,20). In agreement with previous studies, the results from the present study demonstrated that HAD-B induces apoptosis of LLC cells in a macrophage-dependent manner.

Functional reprogramming of TAMs is regarded as a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer inhibition (4,15). Cancer cells are capable of educating macrophages into a M2 phenotype, which possess anti-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic effects. In addition, a high density of M2 showed positive correlation with prognostic factors, including size, stage, metastasis, and histological grade of the tumor (21,22). Thus, a number of studies are focused on regulating macrophage polarization through inhibiting recruitment of monocytes and depletion of monocyte/macrophage lineages by treating chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and docetaxel, low-dose ionized radiation, and neutralizing antibodies for cytokines, including CD40 and colony stimulating factor-1 (6,13). However, these strategies are not ideal, since recruited macrophages can be used to enhance the immune response or to potentiate chemotherapy specificity (23). Suppression of tumor growth can also be achieved by functionally re-educating TAMs, rather than by eradiating them. Thus, to switch macrophages to M1, several small molecule inhibitors against STAT3, STAT6, p50 subunit of NF-κB and IKKβ are now being developed (13).

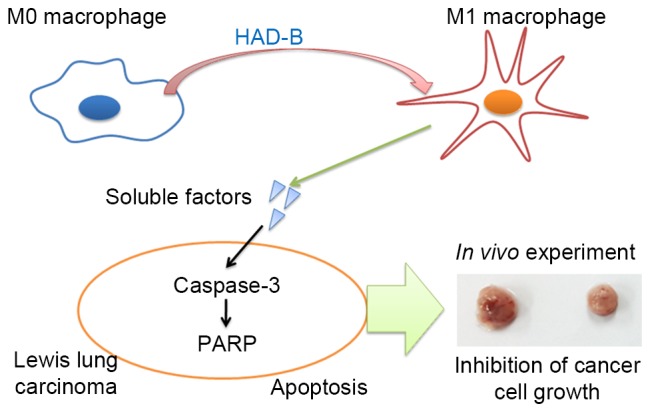

In the present study, results demonstrated that HAD-B can suppress the growth of LLC cells through driving macrophages toward M1 polarization, but not direct inhibition of tumor cell growth. In vivo experiments also showed inhibition of allograft LLC cells using immunocompetent mice (Fig. 5). In addition to previously reported anti-angiogenic (24) and anti-metastatic (7) effects, results from the present study suggest that the anti-cancer effect of HAD-B may be due to re-education of macrophages toward the M1 phenotype. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence of the immunomodulatory action of HAD-B. To elucidate which ingredient herbs or compounds are responsible for switching macrophage phenotype, more extensive studies are required. Considering the importance of re-educating TAMs in the regulation of tumor microenvironment, the present study may confer another option for anti-cancer therapeutic strategy using herbal medicine including HAD-B.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the mechanism underlying antitumor action of HAD-B. Although HAD-B itself did not show any inhibitory effect on tumor cell growth, tumor cell growth was reduced by HAD-B treatment in the in vivo and in vitro experiments. The culture media from HAD-B-treated macrophages can suppress tumor growth. In addition, HAD-B polarizes macrophages to a M1 phenotype. Thus, the soluble factors secreted from HAD-B-treated macrophages can induce apoptosis of tumor cells. PARP, poly-ADP-ribose polymerase.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MISP), of the Korean Government (grant no. 2014R1A5A20009936).

References

- 1.Bhome R, Bullock MD, Al Saihati HA, Goh RW, Primrose JN, Sayan AE, Mirnezami AH. A top-down view of the tumor microenvironment: Structure, cells and signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:33. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen F, Zhuang X, Lin L, Yu P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Hu G, Sun Y. New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: Challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2015;13:45. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006;66:605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostuni R, Kratochvill F, Murray PJ, Natoli G. Macrophages and cancer: From mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jinushi M, Komohara Y. Tumor-associated macrophages as an emerging target against tumors: Creating a new path from bench to bedside. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi YJ, Shin DY, Lee YW, Cho CK, Kim GY, Kim WJ, Yoo HS, Choi YH. Inhibition of cell motility and invasion by HangAmDan-B in NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:1601–1608. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bang JY, Kim KS, Kim EY, Yoo HS, Lee YW, Cho CK, Choi Y, Jeong HJ, Kang IC. Anti-angiogenic effects of the water extract of HangAmDan (WEHAD), a Korean traditional medicine. Sci China Life Sci. 2011;54:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s11427-011-4144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li KC, Heo K, Ambade N, Kim MK, Kim KH, Yoo BC, Yoo HS. Reduced expression of HSP27 following HAD-B treatment is associated with Her2 downregulation in NIH OVCAR-3 human ovarian cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:3787–3794. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KH, Kwon YK, Cho CK, Lee YW, Lee SH, Jang SG, Yoo BC, Yoo HS. Galectin-3-independent down-regulation of GABABR1 due to treatment with korean herbal extract HAD-B reduces proliferation of human colon cancer cells. J pharmacopuncture. 2012;15:19–30. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2012.15.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: Tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: In vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1670–1690. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Tian W, Cai X, Wang X, Dang W, Tang H, Cao H, Wang L, Chen T. Hydrazinocurcumin Encapsuled nanoparticles ‘re-educate’ tumor-associated macrophages and exhibit anti-tumor effects on breast cancer following STAT3 suppression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: Potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engström A, Erlandsson A, Delbro D, Wijkander J. Conditioned media from macrophages of M1, but not M2 phenotype, inhibit the proliferation of the colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and CACO-2. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:385–392. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan A, Hsiao YJ, Chen HY, Chen HW, Ho CC, Chen YY, Liu YC, Hong TH, Yu SL, Chen JJ, Yang PC. Opposite effects of m1 and m2 macrophage subtypes on lung cancer progression. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14273. doi: 10.1038/srep14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genin M, Clement F, Fattaccioli A, Raes M, Michiels C. M1 and M2 macrophages derived from THP-1 cells differentially modulate the response of cancer cells to etoposide. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:577. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigert A, Brüne B. Nitric oxide, apoptosis and macrophage polarization during tumor progression. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchesi F, Cirillo M, Bianchi A, Gately M, Olimpieri OM, Cerchiara E, Renzi D, Micera A, Balzamino BO, Bonini S, et al. High density of CD68+/CD163+ tumour-associated macrophages (M2-TAM) at diagnosis is significantly correlated to unfavorable prognostic factors and to poor clinical outcomes in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2015;33:110–112. doi: 10.1002/hon.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Wang F, Wang L, Huang L, Wang J, Zhang B, Zhang Y. CD163+ tumor-associated macrophage is a prognostic biomarker and is associated with therapeutic effect on malignant pleural effusion of lung cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10592–10603. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–1073. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang JY, Kim EY, Shim TK, Yoo HS, Lee YW, Kim YS, Cho CK, Choi Y, Jeong HJ, Kang IC. Analysis of anti-angiogenic mechanism of HangAmDan-B (HAD-B), a Korean traditional medicine, using antibody microarray chip. Bio Chip J. 2010;4:350–355. [Google Scholar]