Abstract

Objective

To cross-sectionally determine the quantitative relationship of age-adjusted, sex-specific isometric knee extensor and flexor strength to patient-reported knee pain.

Methods

Difference of thigh muscle strength by age, and that of age-adjusted strength per unit increase on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) knee pain scale, was estimated from linear regression analysis of 4553 Osteoarthritis Initiative participants (58% women). Strata encompassing the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in knee pain were compared to evaluate a potentially non-linear relationship between WOMAC pain levels and muscle strength.

Results

In Osteoarthritis Initiative participants without pain, the age-related difference in isometric knee extensor strength was −9.0%/−8.2% (women/men) per decade, and that of flexor strength was −11%/−6.9%. Differences in age-adjusted strength values for each unit of WOMAC pain (1/20) amounted to −1.9%/−1.6% for extensor and −2.5%/−1.7% for flexor strength. Differences in torque/weight for each unit of WOMAC pain ranged from −3.3 to − 2.1%. There was no indication of a non-linear relationship between pain and strength across the range of observed WOMAC values, and similar results were observed in women and men.

Conclusion

Each increase by 1/20 units in WOMAC pain was associated with a ~2% lower age-adjusted isometric extensor and flexor strength in either sex. As a reduction in muscle strength is known to prospectively increase symptoms in knee osteoarthritis and as pain appears to reduce thigh muscle strength, adequate therapy of pain and muscle strength is required in knee osteoarthritis patients to avoid a vicious circle of self-sustaining clinical deterioration.

Keywords: thigh muscle strength, WOMAC knee pain score, minimal clinically important difference, knee osteoarthritis

INTRODUCTION

Muscle strength is highly adaptive to the external/internal environment, e.g. to immobilization1 or training2–4. Thigh muscle strength was found to be substantially reduced in osteoarthritic knees5–7 and to be strongly related to knee function8. Muscle strength, hence, represents an important target for the treatment of disability in the elderly9, and training interventions have been observed to beneficially affect knee pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA)10–16. In a previous study we showed that knees with moderate to severe levels of knee pain (Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Osteoarthritis Index [WOMAC]≥5 [on a 0–20 Likert scale]) displayed significantly lower isometric thigh muscle strength than painless knees, independent of their radiographic KOA status(Kellgren-Lawrence grade [KLG])5. Yet, despite the evidence of a relationship between impaired thigh muscle status in KOA and knee pain5,6,10, the quantitative magnitude of the difference in thigh strength per unit (or the minimal clinically important difference [MCID]) across the spectrum of observed WOMAC pain units is currently unknown. Further, it is unclear, whether the relationship between pain and difference in muscle strength is linear across the spectrum of pain levels, and whether this relationship is similar between men and women. To address the above questions, age has to be taken into account as a confounder of the interaction between pain and muscle strength, as muscle strength decreases with age, independent of pain17–20.

The aim of the current study therefore was to analyze the difference of directly age-adjusted knee extensor and flexor strength per unit on the WOMAC knee pain scale, and per strata comprising MCIDs in knee pain across a wide spectrum of WOMAC pain scores. Specifically, we examined whether the relationship between pain and strength is linear across the WOMAC scale, and whether this pain-strength-association differs between men and women.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) database (clinical data releases 0.2.2; 1.2.2), which includes 4796 participants aged 45–79 years, with various socioeconomic backgrounds21,22. Based on risk factor profile and radiographic and symptomatic osteoarthritis status at enrollment, participants were assigned to either the healthy reference cohort without risk factors of KOA (n=122), the incidence cohort at risk of developing symptomatic KOA (n=3284), or the progression cohort with established symptomatic KOA at the time of enrollment (n=1390)8,21,22. Detailed in- and exclusion criteria for the OAI and the current study have been described previously8.

All participants of the entire OAI cohort without missing demographic data (n=4), WOMAC knee pain scores (n=4) and/or WOMAC function scores (n=23), and isometric knee extensor and flexor strength (n=581) were included (one limb per participant)8. Since some participants were enrolled before the strength measurement device was applied in the study, we also included those with complete data (of the above measures), who had thigh strength measured at the year 1 follow-up visit (219 women/129 men) instead of the baseline measurements. Hence, 4553 participants (2651 women/1902 men) were available for the analysis.

Of these 4553 participants, all participants without any knee pain (WOMAC=0) and without any signs of radiographic KOA (KLG=0) were used to analyze the relationship between age and strength by regression analysis, separately in women and men. The radiographic status was evaluated on fixed-flexion X-rays23 in central KLG readings (versions 0.7 for n=3934 and 1.7 for n=338 participants)24.

Measurement of isometric thigh muscle strength

Amongst the two limbs per OAI participant, the strength data from the dominant limb were used (OAI question: “With which leg do you kick a ball”). When participants considered both limbs as equal (n=65) or when such information was not available (n=38), the right limb was used.

For the maximum isometric knee extensor and flexor strength measurements, the “Good Strength Chair” (Metitur Oy, Jyvaskyla, Finland) was used6,8,25. Participants were seated upright, with pelvis and thigh fixated by straps and the knee flexed at 60°. The load cell was positioned at a consistent anatomical position 2cm proximal to the calcaneus. To get familiarized with the measurement procedure, the participants performed two practice trials at 50% effort, before three measurements with maximum voluntary isometric contraction, i.e. 100% effort, were recorded (in Newton [N]). The maximum value of these three trials was used for the analysis.

Torque was used, to normalize strength with the most appropriate scaling to body weight26. To calculate knee extensor and flexor torque (moment), leg length measurements of the OAI database were used. These were available for the right legs (only) in 4518 participants (58% women) and were also used for the left-dominant participants, assuming symmetry in limb length.

Assessment of self-reported knee pain

For assessment of the patient-reported pain status, the WOMAC knee pain score was used. The scale ranges from 0–20 (0=no pain)27,28. This subscale of the total WOMAC score comprises five questions (Likert scale), each rated from 0–4, where 4 units represent extreme pain. In the OAI, the questions ask for knee-specific, i.e. side-specific, pain when walking, climbing or going down stairs, lying in bed, sitting or lying down, and when standing, within the past seven days. During a rehabilitation intervention, an MCID of 2 units for the WOMAC knee pain score has been previously reported by Angst et al.29.

Assessment of comorbidities and depression

For assessment of the presence of comorbidities, the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index was used30,31. This score provides the only documentation of existing comorbidities such as previous heart attack, oncologic pathologies or asthma, for the OAI database as described previously32. For assessment of depression, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Score33 from the OAI database was used. Participants rated their feelings such as having appetite, feeling depressed, restless, fearful, lonely, happy, sad, hopeful for the future, having crying spells, etc. (20 questions) for the past week from 1 (=rarely or none of the time; <1day) to 4 (=most or all of the time; 5–7days). Both scores were available for 4460 participants (58% women) for the analysis of strength and for 4429 participants (58% women) for the analysis of torque/body weight.

Statistical Analysis

Given previous reports on sex differences in strength between men and women5,34, analyses were performed for men and women separately. Further, analyses were repeated for torque (isometric strength*lever arm of leg length in meter) with normalization to body weight (torque/weight; Newton-meter/kilogram) to account for inter-personal variations and the influence of weight on strength. All analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA).

To estimate the difference in strength per age decade, only participants without knee pain (WOMAC 0) and without radiographic KOA (KLG 0) were included. Linear regression models with age (independent variable), and extensor and flexor strength (dependent variable), were used. The slope coefficient of the regression equation (equation 1) represented the difference in strength per annum, which was then used as the basis for directly adjusting the observed values for age. We calculated the difference per decade by multiplying this slope coefficient with the factor 10. Because 45 was the youngest age for OAI inclusion21,22, this was considered the starting point to relate the difference per decade to (equation 2). By entering 45 in the regression equation, we calculated the strength at age 45 (equation 3). For the direct age-adjustment, we used the slope coefficient calculated in the previous analysis (equation 1). We calculated the theoretical strength of every participant at the mean age of the cohort (61.4 years) using the age-difference to the mean and the actual strength (equation 4).

After direct age-adjustment, linear regression models were used to calculate the difference in thigh muscle strength (torque/body weight) (dependent variable), per unit increase in the WOMAC knee pain score (independent variable). Slope coefficients of the regression equations (equation 5) represented the difference in strength per unit increase in WOMAC knee pain. To compare the association between men and women, the slopes of the regression models were compared based on the standard error of the slopes. Additional linear regression models were used with strength (torque/body weight) as dependent and WOMAC knee pain score, the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the CES-D as independent variables. Analyses were repeated with exclusion of all participants with strength measurements at year 1 of follow-up.

EQUATIONS USED

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Since the MCID for the WOMAC knee pain score has been reported to be 2 units29, participants were divided into strata encompassing 2 WOMAC knee pain units each (0; 1–2; 3–4; 5–6; 7–8; 9–10; 11–12; >12) across the observed WOMAC spectrum to evaluate non-linearity in the dose-response relationship of pain and muscle strength. These strata were compared to the stratum with painless participants (WOMAC=0) and to the next lower WOMAC stratum (1–2 vs 0; 3–4 vs 1–2, etc.). Because only few participants had knee pain worse than WOMAC=12, these participants were combined to one stratum. As a measure of the between-group effect size, Cohen’s d was calculated8. To relate the relevance of a difference in strength (torque/body weight) to the MCID in knee pain, the mean of the %-differences in strength (torque/body weight) between participants being 2 WOMAC units apart (0 vs 2, 1 vs 3, up to 11 vs 13) was calculated.

For exploratory purposes the R2 for the simple linear regression model with strength (torque/body weight), i.e. dependent variable, and WOMAC knee pain score, the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the CES-D, i.e. independent variables, were calculated to estimate how much of the variability in strength and torque/body weight is explained by them.

RESULTS

Demographics and age-adjustment of thigh muscle strength

Of the 2651/1902 women/men studied, 33%/37% were KLG0, 17%/17% KLG1, 29%/23% KLG2, 12%/14% KLG3, and 2%/4% KLG4. For 7% and 5% of the women and men, KLG data was not available. The age was 61.4±9.2 years (mean ±standard deviation [SD]) and the body mass index (BMI) was 28.7±4.8 kg/m2 (Table 1). Demographic data for all WOMAC strata are displayed in Table 1. Women and men in higher WOMAC strata tended to be heavier, but also younger, than those without any pain (WOMAC=0).

Table 1.

Demographic data for women and men for each WOMAC knee pain stratum.

| n | Age years |

BMI kg/m2 |

Body Height cm |

Body Weight kg |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMEN | |||||

| All | 2651 | 61.7 ± 8.9 | 28.5 ± 5.2 | 162.2 ± 6.3 | 75.1 ± 14.6 |

| WOMAC 0 | 1018 | 62.4 ± 9.0 | 27.4 ± 4.9 | 162.0 ± 6.3 | 72.0 ± 14.0 |

| WOMAC 1–2 | 624 | 61.1 ± 8.8 | 28.2 ± 4.9 | 162.4 ± 6.3 | 74.3 ± 13.8 |

| WOMAC 3–4 | 379 | 61.6 ± 8.6 | 28.7 ± 5.0 | 162.3 ± 6.5 | 75.6 ± 14.3 |

| WOMAC 5–6 | 252 | 61.2 ± 9.3 | 29.6 ± 5.1 | 162.0 ± 6.1 | 77.9 ± 14.8 |

| WOMAC 7–8 | 158 | 62.6 ± 8.9 | 30.2 ± 4.9 | 162.2 ± 6.1 | 79.5 ± 13.5 |

| WOMAC 9–10 | 113 | 59.5 ± 8.5 | 31.7 ± 5.7 | 162.1 ± 6.9 | 83.4 ± 16.2 |

| WOMAC 11–12 | 64 | 59.5 ± 7.8 | 31.1 ± 6.0 | 162.6 ± 6.3 | 82.2 ± 15.7 |

| WOMAC >12 | 43 | 59.9 ± 9.8 | 32.8 ± 6.2 | 164.7 ± 7.1 | 88.5 ± 16.0 |

| MEN | |||||

| All | 1902 | 61.1 ± 9.5 | 28.9 ± 4.1 | 176.6 ± 8.1 | 90.1 ± 14.5 |

| WOMAC 0 | 851 | 61.2 ± 9.6 | 28.4 ± 3.9 | 176.7 ± 6.7 | 88.7 ± 13.7 |

| WOMAC 1–2 | 450 | 61.4 ± 9.4 | 28.6 ± 4.0 | 176.8 ± 6.8 | 89.3 ± 13.9 |

| WOMAC 3–4 | 284 | 61.3 ± 9.6 | 29.2 ± 4.0 | 176.7 ± 7.5 | 91.3 ± 14.1 |

| WOMAC 5–6 | 155 | 60.3 ± 9.1 | 29.9 ± 4.4 | 176.3 ± 6.9 | 93.1 ± 16.0 |

| WOMAC 7–8 | 73 | 60.2 ± 9.2 | 30.9 ± 4.9 | 176.3 ± 8.0 | 96.3 ± 17.5 |

| WOMAC 9–10 | 50 | 59.5 ± 9.3 | 29.9 ± 4.7 | 175.5 ± 8.7 | 92.0 ± 15.8 |

| WOMAC 11–12 | 26 | 59.0 ± 10.5 | 30.3 ± 5.0 | 174.8 ± 6.0 | 92.8 ± 17.7 |

| WOMAC >12 | 13 | 59.5 ± 7.0 | 32.0 ± 4.2 | 181.2 ± 5.5 | 105 ± 15.6 |

Demographic data for time point of strength measurement, i.e. n=4205 at baseline and n=348 at year 1 follow-up; n=participant number; BMI=body mass index; kg/m2= kilogram per meter2; cm=centimeter;

798 participants (426 women/372 men) without knee pain and without radiographic KOA were included. The 426 women were 60.7±9.0 years old and had a BMI of 26.2±4.7 kg/m2 (68.3±13.2 kg body weight). The 372 men were 59.0±9.4 years old and had a BMI of 27.6±3.7 kg/m2 (86.1±13.2 kg body weight).

Extensor muscle strength was found to be 9.0%/8.2% lower per decade relative to 354N/530N at 45 years of age in the pain-free limbs of women/men (R2=0.11/R2=0.09; p<0.0001 in both sexes) (Figure 1). Flexor muscle strength was found to be 10.8%/6.9% lower (R2=0.09/R2=0.03; p<0.0001 in both sexes) relative to 146N/217N. Extensor and flexor torque/body weight in women/men were 6.4%/6.7% (R2=0.04/R2=0.06) (Figure 1) and 8.0%/8.2% (R2=0.03/R2=0.04) lower per decade, respectively.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots showing the association between age (X axis) and knee extensor strength (Y axis) for in women (A) and in men (B) and that between age and isometric knee extensor torque per body weight in women (C) and men (D).

Relationship between age-adjusted thigh muscle strength and self-reported knee pain

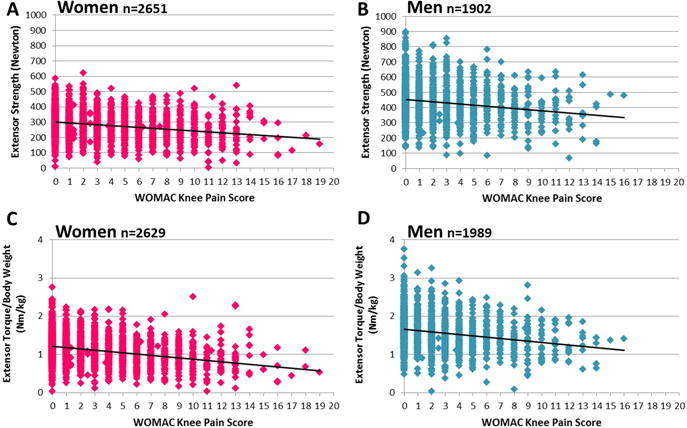

For example, when calculating the difference in strength, the regression equation for WOMAC knee pain versus extensor strength was Y=300.619−5.859x. Hence, the difference of extensor strength/unit of the WOMAC knee pain score, i.e. the slope, was −5.859N. The value of −5.859N was divided by the y-intercept=300.619N(*100) to extract the −1.9% difference (−5.9N; R2=0.053) in directly age-adjusted isometric extensor strength per unit WOMAC knee pain in women, and the −1.6% strength difference (−7.4N; R2=0.029) in men (y-intercept: 452.333, slope coefficient: −7.365) (Figure 2). The difference in directly age-adjusted flexor strength was −2.5% (−3.0N; R2=0.048) in women and −1.7% (−3.3N; R2=0.017) in men. For directly age-adjusted extensor torque/body weight (Figure 2) and flexor torque/body weight, differences amounted to 2.7% (R2=0.092) and 3.3% lower strength (R2=0.077) in women and 2.1% (R2=0.044) and 2.2% (R2=0.026) lower strength in men, respectively.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots showing the association between the Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) knee pain score (range 0–20; 20=worst pain; X axis) and age-adjusted knee extensor strength (Y axis) in women (A) and in men (B) and that of age-adjusted isometric knee extensor torque per body weight in women (C) and men (D).

The differences in extensor strength (y-intercept: 300.962, slope coefficient: −5,695 in women; y-intercept: 459.091, slope coefficient: −7.075 in men) and flexor strength as well as torque/body weight remained largely unchanged (ranging from 1.5 to 3.1%) after adjusting for the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index and the CES-D and in participants with baseline strength measurements only (data not shown).

A clear trend was observed for participants in strata with more severe pain to exhibit lower extensor and flexor strength (torque/body weight), in women and men. Women without knee pain (WOMAC=0) had an extensor strength of 300±86N (304±81N after age-adjustment) and men an extensor strength of 459±130N (458±124N) (Tables 2&3). Women and men in the stratum with the strongest pain (WOMAC>12) had a 24% and 19% lower extensor strength compared to those with WOMAC=0 (Tables 2&3). The observed %-differences in strength (torque/body weight) for each pain stratum vs the painfree (WOMAC=0) knees did not suggest that the relationship between pain and thigh strength was non-linear, i.e. the differences in strength between strata were similar across the entire range of WOMAC pain values (Table 2&3). The differences in strength and torque/body weight appeared somewhat greater in women than in men (Tables 2&3), but the slopes of the regression models relating strength to pain did not statistically differ between sexes (p≥0.17).

Table 2.

Women: Strength and torque/body weight (age-adjusted values in brackets) in WOMAC strata, with percent differences to WOMAC 0 and to the next lower WOMAC stratum.

| WOMAC Pain Strata | %Diff vs WOMAC =0‡ | Cohen d‡ | %Diff vs next WOMACΔ,‡ | %Diff vs WOMAC =0‡ | Cohen d‡ | %Diff vs next WOMACΔ,‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extensor Strength | Flexor Strength | |||||||||

| 0 | 300±86 | (304±81) | ref. | ref. | 118±46 | (119±44) | ref. | ref. | ||

| 1–2 | 291±89 | (290±85) | −4.4 | −0.16 | −4.4 | 116±47 | (115±45) | −3.6 | −0.10 | −3.6 |

| 3–4 | 273±85 | (273±81) | −9.9 | −0.37 | −5.8 | 108±47 | (108±46) | −9.5 | −0.26 | −6.2 |

| 5–6 | 268±85 | (267±83) | −12.0 | −0.45 | −2.4 | 101±45 | (100±44) | −15.9 | −0.44 | −7.1 |

| 7–8 | 253±88 | (256±87) | −15.6 | −0.58 | −4.0 | 98±46 | (99±44) | −16.8 | −0.46 | −1.0 |

| 9–10 | 266±89 | (260±89) | −14.4 | −0.36 | +1.4 | 100±42 | (97±44) | −19.0 | −0.31 | −2.7 |

| 11–12 | 228±88 | (222±90) | −26.9 | −1.00 | −14.7 | 75±47 | (72±46) | −39.7 | −1.08 | −25.5 |

| >12 | 235±105 | (230±107) | −24.2 | −0.89 | +3.8 | 87±56 | (84±58) | −29.4 | −0.80 | +17.0 |

| Extensor Torque/BW | Flexor Torque/BW | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.22±0.4 | (1.23±0.4) | ref. | ref. | 0.48±0.2 | (0.48±0.2) | ref. | ref. | ||

| 1–2 | 1.15±0.4 | (1.15±0.4) | −6.3 | −0.22 | −6.3 | 0.46±0.2 | (0.46±0.2) | −5.4 | −0.14 | −5.4 |

| 3–4 | 1.06±0.4 | (1.06±0.3) | −13.3 | −0.46 | −7.5 | 0.42±0.2 | (0.42±0.2) | −13.0 | −0.33 | −8.1 |

| 5–6 | 1.01±0.3 | (1.01±0.3) | −17.8 | −0.61 | −5.2 | 0.38±0.2 | (0.38±0.2) | −21.1 | −0.54 | −9.3 |

| 7–8 | 0.94±0.3 | (0.94±0.3) | −23.0 | −0.79 | −6.3 | 0.36±0.2 | (0.36±0.2) | −24.5 | −0.63 | −4.3 |

| 9–10 | 0.95±0.4 | (0.93±0.3) | −24.0 | −0.66 | −1.3 | 0.35±0.1 | (0.35±0.2) | −28.2 | −0.52 | −4.9 |

| 11–12 | 0.84±0.3 | (0.82±0.3) | −33.1 | −1.13 | −12.0 | 0.27±0.2 | (0.27±0.1) | −44.9 | −1.15 | −23.3 |

| >12 | 0.85±0.5 | (0.84±0.5) | −31.5 | −1.06 | +2.5 | 0.31±0.2 | (0.30±0.2) | −37.0 | −0.93 | +14.4 |

Mean±standard deviation; %Diff=percent difference; WOMAC=WOMAC knee pain score; ref=reference; BW= body weight;

compared to the next lower WOMAC stratum (1–2 vs 0; 3–4 vs 1–2; 5–6 vs 3–4,…);

calculated using age-adjusted strength values

Table 3.

Men: Strength and torque/body weight (age-adjusted values in brackets) in WOMAC strata, with percent differences to WOMAC 0 and to the next lower WOMAC stratum.

| WOMAC Pain Strata | %Diff vs WOMAC =0‡ | Cohen d‡ | %Diff vs next WOMACΔ,‡ | %Diff vs WOMAC =0‡ | Cohen d‡ | %Diff vs next WOMACΔ,‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extensor Strength | Flexor Strength | |||||||||

| 0 | 459±130 | (458±124) | ref. | ref. | 192±77 | (192±76) | ref. | ref. | ||

| 1–2 | 431±123 | (431±116) | −5.9 | −0.22 | −5.9 | 177±74 | (177±72) | −7.8 | −0.20 | −7.8 |

| 3–4 | 423±129 | (423±121) | −7.7 | −0.29 | −1.9 | 175±72 | (175±69) | −8.6 | −0.22 | −0.9 |

| 5–6 | 416±123 | (412±115) | −10.2 | −0.38 | −2.6 | 183±75 | (181±72) | −5.6 | −0.14 | +3.3 |

| 7–8 | 415±117 | (410±114) | −10.5 | −0.39 | −0.4 | 159±73 | (157±72) | −18.2 | −0.46 | −13.3 |

| 9–10 | 385±121 | (377±117) | −17.8 | −0.66 | −8.1 | 159±68 | (156±66) | −18.8 | −0.48 | −0.7 |

| 11–12 | 386±125 | (375±129) | −18.1 | −0.67 | −0.5 | 156±62 | (152±64) | −20.8 | −0.53 | −2.4 |

| >12 | 380±128 | (371±143) | −19.0 | −0.70 | −1.0 | 165±68 | (162±73) | −15.6 | −0.40 | +6.5 |

| Extensor Torque/BW | Flexor Torque/BW | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.68±0.5 | (1.68±0.5) | ref. | ref. | 0.70±0.3 | (0.70±0.3) | ref. | ref. | ||

| 1–2 | 1.58±0.5 | (1.58±0.5) | −5.7 | −0.21 | −5.7 | 0.65±0.3 | (0.65±0.3) | −7.5 | −0.20 | −7.5 |

| 3–4 | 1.50±0.5 | (1.50±0.4) | −10.5 | −0.39 | −5.1 | 0.62±0.3 | (0.62±0.2) | −11.2 | −0.30 | −4.0 |

| 5–6 | 1.46±0.4 | (1.45±0.4) | −13.7 | −0.50 | −3.6 | 0.63±0.2 | (0.63±0.2) | −10.3 | −0.27 | +1.1 |

| 7–8 | 1.43±0.4 | (1.41±0.4) | −15.7 | −0.58 | −2.3 | 0.55±0.2 | (0.54±0.2) | −22.3 | −0.58 | −13.3 |

| 9–10 | 1.38±0.5 | (1.36±0.5) | −18.8 | −0.68 | −3.7 | 0.57±0.3 | (0.56±0.2) | −19.6 | −0.51 | +3.5 |

| 11–12 | 1.41±0.4 | (1.37±0.4) | −18.1 | −0.66 | +0.8 | 0.57±0.2 | (0.55±0.2) | −21.5 | −0.56 | −2.4 |

| >12 | 1.27±0.3 | (1.24±0.4) | −25.8 | −0.94 | −9.3 | 0.55±0.2 | (0.54±0.2) | −23.2 | −0.60 | −2.1 |

Mean±standard deviation; %Diff=percent difference; WOMAC=WOMAC knee pain score; ref=reference; BW= body weight;

compared to the next lower WOMAC stratum (1–2 vs 0; 3–4 vs 1–2; 5–6 vs 3–4,…)

calculated using age-adjusted strength values

The MCID of the WOMAC knee pain score across all 2-unit WOMAC score comparisons related to a 3.7% lower extensor strength and 4.7% lower extensor torque/body weight in women and to a 3.1% and 3.6% lower strength and torque/body weight in men, respectively. For flexor strength and torque/body weight %-differences were −4.6% and −5.1% in women and −2.6% and −2.9% in men.

The effect of comorbidities and depression on age-adjusted thigh muscle strength

In the linear regression model in men the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, but not the CES-D score, had a significant independent effect on knee extensor and flexor strength (p=0.005 and 0.03) additionally to the WOMAC knee pain score (p<0.0001). With the WOMAC knee pain score as the only independent variable in the linear regression model, R2 was 0.031 for extensor and 0.017 for flexor strength and with all three scores added into the model, R2 was 0.036 and 0.021. In women, however, neither the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index nor the CES-D significantly explained any variability (0%) in extensor or flexor strength (p≥0.07).

When extensor and flexor torque/body weight were the dependent variables, the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, but not the CES-D, had a significant, independent effect on torque/body weight in men (p≤0.007) and in women (p<0.0001). With the WOMAC knee pain score as the only independent variable in the linear regression model R2 was 0.092 for extensor and R2=0.074 for flexor torque/body weight in women and R2=0.046 and R2=0.027 in men and when all three scores were added into the model, R2 was 0.098 for extensor and R2=0.079 for flexor torque/body weight in women and R2=0.056 and R2=0.033 in men.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the dose-response relationship between knee pain and sex-specific, age-adjusted thigh muscle strength across a large range of WOMAC knee pain scores. In the OAI cohort, we found age-related differences in women/men without knee pain or radiographic KOA in extensor strength to be 9%/8% lower, and those in flexor strength to be 11%/7% lower/decade, when related to 45 years (i.e. youngest age for OAI enrollment). These differences were accounted for when exploring the impact of pain on (directly age-adjusted) muscle strength. We found an increase of 1 unit on the WOMAC knee pain scale to be associated with a 2–3% lower knee extensor and flexor strength and torque/body weight in both women and men. As an estimate of an MCID in strength, a 3–5% lower strength (torque/body weight) was related to the MCID in pain. Across WOMAC knee pain strata of 2 units (=MCID29), there was no evidence for a non-linear dose-response relationship between WOMAC knee pain and thigh muscle strength in either sex.

A limitation of the current study is its cross-sectional approach that precluded an evaluation of longitudinal changes within subjects, and the impact of longitudinal changes in WOMAC pain on that of thigh muscle strength. However, although the current study is limited to a cross-sectional setting, it permits the analysis of an age-related difference in strength over an extensive period of time, since the age-range of the participants included in this very large cohort covered a range of 34 years (45 to 79 years). The current findings lack a comparison with a healthy reference cohort, as only 26 of 122 healthy OAI participants had baseline strength measurements. Therefore, age-related adjustments in strength were estimated in those with risk factors for, but without established symptomatic or radiographic KOA, with the estimated percent rates of changes for women and men being in line with previous literature35. It is of note that, despite their statistical significance, the strength of the relationship (R2 values), for instance between age and muscle strength, was relatively low. Therefore, the findings should not be generalized at an individual level.

Using age as covariate would have offered the advantage that the statistical model accounts for each individual’s age and, hence, each individual’s strength at the respective age. However, this might also have introduced interactions between pain and aging into the model (slope of the regression equation). We therefore used a subcohort with no knee pain and radiographic changes (WOMAC=0, KLG=0) to circumvent such potential influences. Further, directly adjusting strength to the mean of the cohort, allowed the calculations of differences in directly age-adjusted strength values across MCID strata.

A strength of our study design was that it enabled us to assess the pain-related reduction in age-adjusted strength in a very large cohort at risk of or with established KOA (comprising all KLGs), and across a wide range of WOMAC knee pain scores. The WOMAC knee pain score is a thoroughly validated27,28 and extensively applied tool for assessing patient-reported pain with a well-defined MCID29. An additional advantage was the knee-specific application of the questionnaire for the OAI. For the linear regression models, the WOMAC knee pain score was treated as continuous variable. However, for the question of the linearity of the pain-strength-relationship the MCID, although originally established as a measure to follow-up participants over time, provided a means to estimate a difference in strength in the context of a validated and relevant difference in knee pain.

Another limitation of the current study is the use of isometric strength. Compared to isometric strength, isokinetic strength might have the advantage of a potentially stronger correlation to lower leg function36 which, in turn, is largely determined by knee pain8 as WOMAC knee pain and WOMAC function scores are highly correlated (R=0.85 in women; R=0.78 in men) in the OAI cohort8. Hence, isokinetic training was shown to be more effective for strength and pain improvement than isometric training37. However, isometric strength measurements are robust – especially when using more than one trial38 – and easy to apply in a large cohort such as the OAI22. Knee pain during an actual isokinetic strength measurement may be affected by the angular velocity39 and decreases strength measures40, whereas for isometric strength it was suggested that knee pain does not significantly affect the actual measurement41.

For the current study, we did account for the influence of weight42 on thigh muscle strength as well as on knee pain43 by normalizing torque to body weight. Torque was used for this purpose to attain the most appropriate scaling with body weight (mass) with Newton-meter:body weight as 1:126,44. In the OAI, no data on muscle mass was acquired to directly normalize strength to the actual mass of the muscles. However, the overall body mass might be the better surrogate for interpersonal differences as it may also take into account obesity26, which in turn favors knee pain45. Therefore, the actual body mass may also be more important in view of functional limitations, which are mainly driven by knee pain8, as it allows a better estimate of the work the muscles have to exert26. Unfortunately, the distance between the axis of rotation and the application of force was not available from the OAI database, but the distance between the transducer and the knee joint line was available and was used for this analysis. Yet, we assume that both distances are highly related and that therefore the correlations are not affected, albeit absolute values may differ for both measurements. Further, similar results were observed for actual strength measures and torque/body weight. Hence, this consistency between both measures, i.e. actual force (N) and torque/body weight (Nm/kg), suggests that both ways provide an appropriate tool to evaluate pain-strength-relations.

We did not adjust for KLG in the analyses, as we previously5 found the association of knee pain with strength to be independent of the radiographic disease stage (KLG). However, we did adjust for potential confounders of knee pain and strength, i.e. depression46 and comorbidities47, but they only explained a minimal portion, if any, of the variability in strength and torque/body weight. The CES-D appeared to have no additional effect, when we also adjusted for comorbidities. This might reflect the high proportion of participants with low scores and a potential inter-relation between comorbidities with depression48 and also knee pain.

Knee flexor strength was also included in the current analysis, as hamstring strengthening has proven to have additional beneficial effects on the WOMAC knee pain score compared to quadriceps strengthening alone13,16. Thus, the observed 2–3% lower flexor strength and torque/body weight per increase of one WOMAC knee pain unit supports previous findings on the importance of flexor strength in context of knee pain in either sex13,16.

Knee pain and thigh muscle strength are significantly associated with each other. Previous literature has suggested that a reduction in thigh muscle strength may cause knee pain49. However, there also is evidence that knee pain causes a reduction in thigh muscle strength50, with the quantification of specific pain levels across the entire WOMAC range on thigh muscle strength representing the scope of the current study. The current findings suggest that the association of knee pain with thigh muscle strength does not differ between sexes, and that these relations do not appear to be non-linear. This emphasizes that adequate pain treatment is important across the entire range of knee pain levels, with the aim of maintaining muscle strength and of breaking a vicious circle of increasing pain and declining muscle strength and knee function8. However, neither men nor women reached the maximum pain score of 20 (1 man with WOMAC=16 and 2 men with WOMAC=15; 1 woman with WOMAC=19 and 2 women with WOMAC=18 as the highest scores). There were only a few participants within the stratum >12 units on the WOMAC knee pain scale and, hence, strength (torque) might plateau when approaching the end of the WOMAC knee pain scale which appears hard to reach even in a large cohort. Our findings of lower strength in the presence of knee pain are in line with previous literature focusing on OAI participants with moderate/severe levels of knee pain in a cross-sectional study design5,6: A between-knee, within-person study reported an 8% lower isometric knee extensor strength in painful knees (mean WOMAC= 4.4) versus contra-lateral painless knees (mean WOMAC=0.6). Further, in our previous study, participants with WOMAC≥5 had 11–17% lower knee extensor strength and 9–21% lower flexor strength compared to painless (WOMAC=0) women and men5. Hence, the current study extends these findings and suggests that mild levels of knee pain are also associated with lower thigh muscle strength, and that the association between pain and age-adjusted strength does not appear to be non-linear across the spectrum of WOMAC pain scores. However, longitudinal studies are needed for confirmation of these findings.

In conclusion, an approximately 2% lower directly age-adjusted isometric extensor and flexor strength and an approximately 2–3% lower torque/body weight is related to each 1-unit increase on the WOMAC knee pain scale, both in men and women. Comparing WOMAC pain strata across the full observed spectrum did not indicate that the difference in directly age-adjusted isometric muscle strength is non-linear. As a reduction in muscle strength is known to prospectively increase symptoms in KOA and as pain appears to reduce thigh muscle strength, adequate therapy of pain and muscle strength is required in knee OA patients to avoid a vicious circle of self-sustaining clinical deterioration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the OAI participants, OAI investigators and OAI Clinical Center’s staff for generating this publicly available image and clinical data set. The data were acquired by the OAI, a public-private partnership comprised five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institute of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners of the OAI include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institute of Health. The statistical analysis presented in the current study was supported by funds from the Paracelsus Medical University Research Fund (PMU FFF R-13/05/055-RUH).

Role of the funding source

The funding sources took no active part of influence on the analysis of the data and in drafting or revising the article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author’s Contribution

All authors have made substantial contributions to: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Disclosure of interest

Felix Eckstein is CEO and is co-owner of Chondrometrics GmbH, a company providing MR image analysis services. He provides consulting services to MerckSerono, Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, and Abbot. Wolfgang Wirth is part-time employed and is co-owner of Chondrometrics GmbH, and provides consulting services to MerckSerono. Anja Ruhdorfer has no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Booth FW. Terrestrial applications of bone and muscle research in microgravity. Adv sp Res. 1994;14(8):373–376. doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(94)90425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudelmaier M, Wirth W, Himmer M, Ring-Dimitriou S, Sänger A, Eckstein F. Effect of exercise intervention on thigh muscle volume and anatomical cross-sectional areas--quantitative assessment using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(6):1713–1720. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracy BL, Ivey FM, Hurlbut D, Martel GF, Lemmer JT, Siegel EL, et al. Muscle quality. II. Effects of strength training in 65- to 75-yr-old men and women Muscle quality. J Appl Physiol. 2013;86(1):195–201. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson ED, Srivatsan SR, Agrawal S, Menon KS, Delmonico MJ, Wang MQ, et al. Effects of strength training on physical function: influence of power, strength, and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:1533–4287. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b2297b. (Electronic)): 2627–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhdorfer A, Wirth W, Hitzl W, Nevitt M, Eckstein F. Association of thigh muscle strength with knee symptoms and radiographic disease stage of osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(9):1344–1353. doi: 10.1002/acr.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sattler M, Dannhauer T, Hudelmaier M, Wirth W, Sänger a M, Kwoh CK, et al. Side differences of thigh muscle cross-sectional areas and maximal isometric muscle force in bilateral knees with the same radiographic disease stage, but unilateral frequent pain – data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(6):532–540. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennell KL, Wrigley TV, Hunt MA, Lim BW, Hinman RS. Update on the role of muscle in the genesis and management of knee osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:1558–3163. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.11.003. (Electronic)): 145–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruhdorfer A, Wirth W, Eckstein F. Relationship between isometric thigh muscle strength and minimum clinically important differences in knee function in osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67(4):509–518. doi: 10.1002/acr.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung S, Yabushita N, Kim M, Seino S, Nemoto M, Osuka Y, et al. Obesity and muscle weakness as risk factors for mobility limitation in community-dwelling older Japanese women: A two-year follow-up investigation. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(1):28–34. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263–1273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennell KL, Hinman RS. A review of the clinical evidence for exercise in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knoop J, Steultjens MPM, Roorda LD, Lems WF, van der Esch M, Thorstensson CA, et al. Improvement in upper leg muscle strength underlies beneficial effects of exercise therapy in knee osteoarthritis: secondary analysis from a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafez AR, Al-Johani AH, Zakaria AR, Al-Ahaideb A, Buragadda S, Melam GR, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis in relation to hamstring and quadriceps strength. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25(11):1401–1405. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, Lim BW, Hinman RS. Role of muscle in the genesis and management of knee osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:1558–3163. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.05.005. (Electronic)): 731–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Reilly SC, Muir KR, Doherty M. Effectiveness of home exercise on pain and disability from osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58(1):15–19. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Johani AH, Kachanathu SJ, Ramadan Hafez A, Al-Ahaideb A, Algarni AD, Meshari Alroumi A, et al. Comparative study of hamstring and quadriceps strengthening treatments in the management of knee osteoarthritis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(6):817–820. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Visser M, Park SW, Conroy MB, Velasquez-Mieyer P, et al. Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(6):1579–1585. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Fielding RA, Fiatarone MA, Evans WJ, Roubenoff R. Aging of skeletal muscle: a 12-yr longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(4):1321–1326. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell WK, Williams J, Atherton P, Larvin M, Lund J, Narici M. Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Front Physiol. 2012 Jul;3:260. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Wood M, Evans WJ, Dallal GE, Roubenoff R, et al. Longitudinal muscle strength changes in older adults: influence of muscle mass, physical activity, and health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(5):B209–B217. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.5.b209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckstein F, Wirth W, Nevitt MC. Recent advances in osteoarthritis imaging-the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012 May;8:1–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nevitt MC, Felson DT, Lester G. The Osteoarthritis Initiative: Protocol for the Cohort Study. 2006 Jun;:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthr Cart. 2008;16(12):1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. RADIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF OSTEO-ARTHROSIS. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rantanen T, Era P, Heikkinen E. Maximal isometric strength and mobility among 75-year-old men and women. Age Ageing. 1994;23(2):132–137. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrigley TV. Correlations With Athletic Performance. In: Brown LE, editor. Isokinetics in Human Performance. Champaign, IL, USA: Human Kinetics Pub Inc; 2000. pp. 42–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW. A preliminary evaluation of the dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5(2):231–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02032362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G. Smallest detectable and minimal clinically important differences of rehabilitation intervention with their implications for required sample sizes using WOMAC and SF-36 quality of life measurement instruments in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower ex. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(4):384–391. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<384::AID-ART352>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruhdorfer A, Wirth W, Eckstein F. Longitudinal change in thigh muscle strength prior and concurrent to a minimal clinically important worsening or improvement in knee function – Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 2016;68(4):826–836. doi: 10.1002/art.39484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger MJ, McKenzie CA, Chess DG, Goela A, Doherty TJ. Sex Differences in Quadriceps Strength in OA. Int J Sports Med. 2012 Jun; doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doherty TJ. Invited review: Aging and sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(4):1717–1727. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madsen OR, Bliddal H, Egsmose C, Sylvest J. Isometric and Isokinetic Quadriceps Strength in Gonarthrosis; Inter-Relations between Quadriceps Strength, Walking Ability, Radiology, Subchondral Bone Density and Pain. Clin Rheumatol. 1995;14:0770–3198. doi: 10.1007/BF02208344. (Print)): 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosa UH, Velasquez TJ, Lara MC, Villarreal RE, Martinez GL, Vargas Daza ER, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of isokinetic vs isometric therapeutic exercise in patients with osteoarthritis of knee. Reumatol Clin. 2012;8:1885–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2011.08.001. (Electronic)):10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skou ST, Simonsen O, Rasmussen S. Examination of muscle strength and pressure pain thresholds in knee osteoarthritis: test-retest reliability and agreement. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38(3):141–147. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almosnino S, Brandon SCE, Sled EA. Does choice of angular velocity affect pain level during isokinetic strength testing of knee osteoarthritis patients? Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48(4):569–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henriksen M, Rosager S, Aaboe J, Graven-Nielsen T, Bliddal H. Experimental knee pain reduces muscle strength. J Pain. 2011;12(4):460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riddle DL, Stratford PW. Impact of pain reported during isometric quadriceps muscle strength testing in people with knee pain: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Phys Ther. 2011;91(11):1478–1489. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bale P. The relationship of physique and body composition to strength in a group of physical education students. Br J Sports Med. 1980;14(4):193–198. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.14.4.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atukorala I, Makovey J, Lawler L, Messier SP, Bennell K, Hunter DJ. Is there a dose response relationship between weight loss and symptom improvement in persons with knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 doi: 10.1002/acr.22805. ([Epub ahead of print]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaric S, Radosavljevic-Jaric S, Johansson H. Muscle force and muscle torque in humans require different methods when adjusting for differences in body size. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;87(3):304–307. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, Morgan TM, Rejeski WJ, Sevick MA, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1501–1510. doi: 10.1002/art.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White DK, Keysor JJ, Neogi T, Felson DT, Lavalley MP, Gross KD, et al. When it hurts, a positive attitude may help: association of positive affect with daily walking in knee osteoarthritis. Results from a multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(9):1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/acr.21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kittelson AJ, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Schmiege SJ. Determination of Pain Phenotypes in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Latent Class Analysis using Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015 doi: 10.1002/acr.22734. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kennedy GJ, Castro J, Chang M, Chauhan-James J, Fishman M. Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidity in the Primary Care Geriatric Patient-An Update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(7):62. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0700-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glass NA, Torner JC, Frey Law LA, Wang K, Yang T, Nevitt MC, et al. The relationship between quadriceps muscle weakness and worsening of knee pain in the MOST cohort: a 5-year longitudinal study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(9):1154–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott D, Blizzard L, Fell J, Jones G. Prospective study of self-reported pain, radiographic osteoarthritis, sarcopenia progression, and falls risk in community-dwelling older adults. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(1):30–37. doi: 10.1002/acr.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]