Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer, and the second most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide. The top three causes of HCC are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and alcoholic liver disease. Owing to recent advances in direct-acting antiviral agents, HCV can now be eradicated in almost all patients. HBV infection and alcoholic liver disease are expected, therefore, to become the leading causes of HCC in the future. However, the association between alcohol consumption and chronic hepatitis B in the progression of liver disease is less well understood than with chronic hepatitis C. The mechanisms underlying the complex interaction between HBV and alcohol are not fully understood, and enhanced viral replication, increased oxidative stress and a weakened immune response could each play an important role in the development of HCC. It remains controversial whether HBV and alcohol synergistically increase the incidence of HCC. Herein, we review the currently available literature regarding the interaction of HBV infection and alcohol consumption on disease progression.

Keywords: Entecavir, Genetic factors, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Interferon

Core tip: The mechanisms by which alcohol enhances disease progression are less well understood in chronic hepatitis B than in chronic hepatitis C. The association of light-to-moderate alcohol consumption with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection appears modest. Although the threshold amount of alcohol for increasing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risk remains unknown, heavy alcohol consumption significantly accelerates the progression of liver disease to cirrhosis and, ultimately, HCC. Alcohol abuse could impair the response to interferon-α therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients, although not fully confirmed, and can increase the risk of HCC even in patients with low HBV DNA levels during nucleoside/nucleotide therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer, predominantly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the second most common cause of cancer deaths, accounting for about 745000 deaths per year[1]. Approximately 45% of cases studied could be attributed to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, 26% to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, 20% to alcoholic liver disease, and 9% to other causes, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, intake of aflatoxin-contaminated food, diabetes and obesity[2]. Although a highly effective vaccine containing recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) has been available since the early 1980s, HBV infection still affects some 240 million people globally, with the highest rates of infection in Asia and Africa, and is a leading cause of liver-related morbidity[3]. In contrast, owing to recent advances in direct-acting antiviral agents that target specific nonstructural proteins of the virus[4,5], HCV infection is expected to be a rare disease within the next 20 years in the United States[6].

Alcohol abuse is another important public health problem. Worldwide, about 38% of people aged 15 years or older drink alcohol, and those who do drink consume on average 17 liters of pure alcohol annually. The highest consumption rates of alcohol are concentrated in Europe and other countries in the Northern hemisphere. The World Health Organization reported that about 3.3 million deaths, or 5.9% of all global deaths, were attributable to excess alcohol use[7]. In particular, heavy alcohol consumption commonly causes progressive liver fibrosis, which will result in cirrhosis, and finally develop into HCC.

It is, thus, clinically important to determine whether alcohol intake accelerates the progression of liver disease in patients with chronic viral hepatitis (B or C). However, the association of alcohol consumption with chronic hepatitis B in the progression of liver disease has been less extensively studied than that with chronic hepatitis C. Herein, we review the available basic and clinical literature on the impact of alcohol intake on disease progression and treatment outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

BASIC BACKGROUND

Mechanisms of alcohol- and HBV-induced liver damage

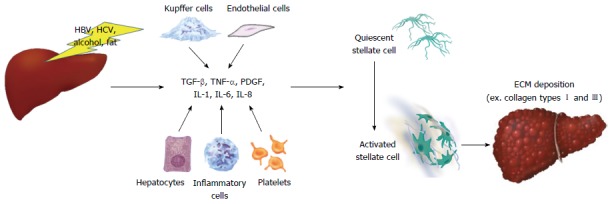

In general, once chronic liver injury of any etiology (hepatitis virus infection, alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) has occurred, damaged hepatocytes, activated sinusoidal cells, platelets, and recruited inflammatory cells release various profibrogenic cytokines, including transforming growth factor-β, and reactive oxygen species, which activate hepatic stellate cells (Figure 1). This process is responsible for deposition of the majority of excess extracellular matrix (predominantly collagen types I and III).

Figure 1.

The mechanisms of activation of hepatic stellate cells during chronic liver injury, resulting in synthesis of excess extracellular matrix. Once chronic liver injury has occurred, damaged hepatocytes, activated sinusoidal cells, platelets, and recruited inflammatory cells release various profibrogenic cytokines, which activate hepatic stellate cells, resulting in synthesis of excess extracellular matrix, such as type I and type III collagens. ECM: Extracellular matrix; IL: Interleukin; PDGF: Platelet-derived growth factor; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

The mechanisms of alcohol-induced liver damage are complex and multifactorial. Ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde, mainly by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in the hepatocyte cytoplasm. This is subsequently oxidized to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in mitochondria. Acetaldehyde is highly toxic, and plays an important role in protein, DNA and hybrid adduct formation, prompting release of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by Kupffer cells, and contributing to immune responses that produce antibodies against aldehyde adducts. Acetaldehyde and aldehydes induce collagen synthesis by activation of transforming growth factor-β-dependent and independent profibrogenic pathways in which cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and osteopontin are involved, activating hepatic stellate cells to promote fibrosis[8]. CYP2E1 is another enzyme involved in the initial steps of alcohol metabolism and its induction is also a key response to alcohol intake, resulting in an increased production of reactive oxidative species, mainly hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion. Oxygen radicals interact with fat molecules in a process called lipid peroxidation. Lastly, alcohol-induced immune abnormalities lead to increased intestinal permeability to a variety of substances, including endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide, which stimulate Kupffer cells by binding with the CD14 receptor to promote fibrosis[9].

On the other hand, HBV is not directly cytopathic; the liver injuries seen in chronic HBV infection are considered to be associated with the activity of HBV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Cytotoxic T cells are activated through the major histocompatibility complex, and proceed to kill infected cells by discharging interferon-γ and TNF-α. HBV infection usually causes inflammatory reactions characterized by the release of cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-8, and TNF-α. The oxidative stress induced by inflammation triggers Kupffer cells to promote stellate cell activation via nuclear factor-κB and activator protein 1. The persistent activation of these genes promotes fibrosis, leading to cirrhosis, and finally to the development of HCC[10].

Interplay between alcohol and HBV in liver disease progression

Although the mechanisms underlying the complex interaction between alcohol and hepatitis virus infection in the progression of liver disease are not fully understood, possible explanations include effects on viral replication, increases in oxidative stress, and a weakening of the immune response[11].

Larkin et al[12] reported that in HBV transgenic C.B-17 SCID mice fed a standard Lieber-DeCarli ethanol liquid diet, elevated levels of HBV RNA as replicative intermediates, and increased expression of HBs, core and X antigens were observed in the liver. With ethanol, the level of HBsAg and of viral DNA in serum increased by up to 7-fold compared with mice fed the control diet. These findings may provide a partial explanation for the effects of alcohol on viral replication and the high frequency of HBV markers observed among alcoholics. Similarly, Min et al[13] showed that in human HepAD38 hepatoma cells infected with HBV, 100 mmol ethanol treatment approximately doubled the transcriptional activity of HBV promoters by increasing the expression of nuclear receptors such as hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α. In addition, CYP2E1-induced oxidative stress potentiates the ethanol-induced transactivation of HBV.

Consistent with clinical observations, Ha et al[14] showed that alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was elevated in both control C57BL/6J mice and HBx transgenic mice fed a 25% ethanol liquid diet for 12 wk, relative to water-fed controls. HBx mice showed 1.4-fold higher levels of ALT than did controls and, in histological evaluations, ethanol-fed HBx transgenic livers showed more evident hepatocyte enlargement and fatty changes compared to ethanol-fed control livers, suggesting that HBx compromising of antioxidant defenses promotes alcoholic liver injury.

Lastly, Geissler et al[15] demonstrated that in female BALB/c mice fed the Lieber-DeCarli diet, with 24% of the total caloric intake from ethanol, followed by DNA-based immunization with a plasmid construct containing the pre-S2/S gene, the levels of antibody to hepatitis B surface proteins (anti-HBs) were marginally reduced compared with those in control mice. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and CD4+ T helper cells derived from ethanol-fed mouse spleens responded poorly to increasing concentrations of envelope protein and peptides in vitro, suggesting that chronic ethanol consumption alters the cellular immune responses to a viral structural protein. A weakened immune response may result in not only persistent HBV infection, but also an immune-tolerant state. On the contrary, excess immune response can cause hepatitis exacerbations. The relationship between the protective versus harmful immune response in HBV infection remains to be fully defined in the context of alcohol intervention.

LIGHT-TO-MODERATE ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AND DISEASE PROGRESSION

Although it is well documented that HCV-positive drinkers are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop HCC than abstinent individuals[16-19], whether HBV infection and alcohol consumption synergistically increase the incidence of HCC is still controversial. Table 1 summarizes previous reports concerning the association of light-to-moderate habitual alcohol consumption with risk of HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection. The large-scale, prospective cohort REVEAL-HBV study in Taiwan, which included more than 3500 patients (aged 30-65 years), showed, during a mean follow-up of 11 years, that elevated serum HBV DNA level (≥ 10000 copies/mL) is an independent risk predictor of disease progression to cirrhosis and HCC[20,21]. A regression analysis revealed that male sex, older age, seropositivity for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and habitual alcohol consumption are also significantly associated with the development of HCC. The adjusted HR (with 95%CI) for HCC was 1.6 (1.1-2.4) for habitual alcohol consumption, defined as drinking alcohol ≥ 4 d per week for ≥ 1 year[20]. In contrast, as a predictor of progression to cirrhosis, HBV DNA level was the strongest factor (RR = 10.6; 95%CI: 5.7-19.6) in a Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for HBeAg status and serum ALT level, while habitual alcohol consumption was not associated with the risk for cirrhosis (RR = 0.8; 95%CI: 0.6-1.2)[21]. In some other large-scale studies in Asia, results were in good agreement[22-24]. Specific examples are that Wang et al[23] conducted a prospective community-based cohort study of 2416 HBsAg-positive and 9421 HBsAg-negative male residents in Taiwan for a mean follow-up of 7.8 years, and found that HBsAg-positive men with habitual alcohol consumption (≥ 4 d per week for ≥ 1 year) had an increased risk of HCC compared to HBsAg-positive men without habitual alcohol consumption, but this was not significant (RR = 1.28; 95%CI: 0.78-2.10). Another prospective cohort study in Korea that followed 4495 HBsAg-positive and 433239 HBsAg-negative men for a median observation of 10 years suggested that moderate alcohol consumption (≥ 25 g of ethanol per d) raised the RR of mortality from HCC to 1.13 in HBsAg-positive men but, again, not significantly[24].

Table 1.

Light-to-moderate habitual alcohol consumption and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection

| Author (year) | Country | Design | n | Follow-up, years | Alcohol intake | Relative risk for HCC | Ref. |

| Chen (2006) | Taiwan | Prospective cohort study | 3653 with HBV | 11 | ≥ 4 d/wk for ≥ 1 year | 1.6 | [20] |

| Wang (2003) | Taiwan | Prospective cohort study | 2416 men with HBV | 7.8 | ≥ 4 d/wk for ≥ 1 year | 1.28 | [23] |

| Jee (2004) | South Korea | Prospective cohort study | 4495 men with HBV | 10 | 25 g/d | 1.13 | [24] |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Some study groups developed simple nomograms based on clinical and laboratory variables for predicting the risk of HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection[25-28]. Increased age and higher HBV DNA level were strong risk predictors of HCC development, and were included in all nomograms; male sex and presence of cirrhosis were included in some. Habitual alcohol consumption was included only in the nomogram derived from the REVEAL-HBV study cohorts[25]. In that nomogram, HBeAg-seronegative participants with high HBV DNA loads (≥ 100000 copies/mL) and genotype C infections had the highest risk of HCC, with 7 points added to the overall score, whereas habitual alcohol consumption had a smaller impact, with only 2 points added.

Taken together, light-to-moderate habitual alcohol consumption appears to have, at best, a modest association with disease progression, with approximately a 1.5-fold increased risk; this effect was not always significant, especially in smaller studies.

HEAVY ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AND DISEASE PROGRESSION

Table 2 summarizes previous reports concerning the association between heavy alcohol consumption and risk of HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection. Although there is currently no worldwide consensus, heavy drinking is sometimes defined as consuming more than 60 g/d of alcohol for men and 40 g/d for women[29]. In Italy, Donato et al[30] conducted a case-control study to investigate the dose-effect relationship between alcohol consumption and HCC, separately, in men and women. They enrolled 464 subjects with a first diagnosis of HCC (including 92 with HBV) and 824 subjects unaffected by hepatic diseases (including 44 with HBV), and found a steady linear increase in the odds ratio of HCC with increasing alcohol intake, for values of > 60 g/d in both sexes. In addition, a synergism between alcohol drinking and chronic HBV infection was found, with the odds ratio of 2.13 in HBsAg-positive drinkers consuming > 60 g per day, compared to HBsAg-positive nondrinkers or drinkers of ≤ 60 g/d. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study of 966 cirrhotic patients in Taiwan, with a mean follow-up period of 2.9-5.2 years, the annual incidence of HCC was significantly higher in 632 cirrhotic patients with HBV infection and heavy alcohol consumption (≥ 80 g/d for ≥ 5 years) than in 132 patients with HBV infection alone (9.9% and 4.1%, respectively, P < 0.001) for a RR of 1.33[31]. Likewise, a prospective cohort study in Japan that followed 610 consecutive HBsAg-positive patients for a median observation period of 4.1 years found that cumulative alcohol consumption ≥ 500 kg was independently associated in a multivariate analysis with the carcinogenesis rate, with a RR (95%CI) of 8.37 (2.70-25.93, P = 0.0002)[32]. Regarding mortality, Ribes et al[33] followed 2352 HBsAg-positive patients for 20 years in a prospective cohort study, and found that lifetime alcohol consumption (> 60 g/d) was associated with a 6-fold increase in the risk of death from cirrhosis and HCC.

Table 2.

Heavy alcohol consumption and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection

| Author (year) | Country | Design | n | Follow-up, years | Alcohol intake | Relative risk for HCC | Ref. |

| Donato (2002) | Italy | Case-control study | 464 with HCC (including 92 with HBV) vs 824 controls (including 44 with HBV) | NA | ≥ 60 g/d | 2.13 | [30] |

| Lin (2013) | Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study | 632 cirrhotics with HBV and alcohol vs 132 cirrhotics with HBV alone | 2.9-5.2 | ≥ 80 g/d for ≥ 5 yr | 1.33 | [31] |

| Ikeda (1998) | Japan | Prospective cohort study | 610 with HBV | 4. 1 | 500 kg (cumulative) | 8.37 | [32] |

NA: Not applicable; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

These studies indicate that heavy alcohol intake increases the incidence of HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection, although the risk threshold remains uncertain.

ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AND OUTCOME OF ANTIVIRAL TREATMENT

Since high HBV DNA levels in serum are associated with a higher risk of HCC, the primary aim of chronic hepatitis B treatment is sustained suppression of viral replication. HBV cannot be completely eradicated, due to the persistence of covalently closed circular DNA in the infected cell nucleus. Current guidelines recommend antiviral therapy with pegylated interferon-α or nucleoside/nucleotide analogues, including entecavir and tenofovir, as first-line treatment[34-36].

In HBeAg-positive patients, female sex, high serum ALT level, low HBV DNA level, and genotype A were associated with an increased likelihood of sustained response to interferon-α[37]; there are no strong pre-treatment predictors of viral response in HBeAg-negative patients. In patients with HCV, alcohol abuse appears to decrease responsiveness to interferon therapy, reducing both sensitivity and compliance[38,39]. It was reported that increased oxidative stress from alcohol consumption can impair the cellular response to interferon-α through interference with the JAK-STAT pathway[40,41]. Although there are no data concerning an association between alcohol consumption and treatment outcomes in patients with HBV, probably because fewer patients receive interferon for treatment of chronic hepatitis B, excess alcohol could reduce the efficacy of interferon therapy by the same mechanisms reported for patients with HCV.

In patients receiving nucleoside/nucleotide analogues, high serum ALT levels, high histological activity index scores for necroinflammation, and low HBV DNA levels are pre-treatment factors predictive of favorable biochemical, serological and virological responses[42,43]. Regarding alcohol consumption, Chung et al[44] reported that hazardous drinking (defined as a score of 8 or more on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) had no significant impact on the short-term outcome of 12 mo of entecavir treatment, measured as the rate of HBeAg seroconversion and HBV DNA negativity. Long-term treatment with lamivudine for a median duration of 32.4 mo can prevent progression to end-stage liver disease[45]. Hosaka et al[46] conducted a retrospective case-control study using propensity matching, and found that patients treated with 0.5 mg entecavir were significantly less likely to develop HCC than those in the control group (HR = 0.37; 95%CI: 0.15-0.91; P = 0.030). However, HCC can develop, even in patients with sustained HBV suppression. In addition to older age, presence of cirrhosis, HBeAg positivity, and low platelet count (< 1.5 × 105/mm3), cumulative alcohol consumption > 200 kg was one of the significant factors associated with HCC development, with a multivariate adjusted HR (95%CI) of 2.21 (1.18-4.0).

In short, alcohol abuse could impair the response to interferon-α therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients as well as in chronic hepatitis C patients, and can increase the risk of HCC even in patients with low HBV DNA levels during nucleoside/nucleotide therapy.

GENETIC FACTORS

Albeit still controversial, some reports have associated genetic variants with disease progression. Table 3 is a brief summary of reported genetic polymorphisms potentially associated with increased risk of alcoholic liver disease. In subjects with ADH2*1/*2 or ADH2*1/*1, the rate of ethanol metabolism is lower, compared with those having ADH2*2/*2. ALDH2 gene polymorphism can determine flushing after ethanol ingestion. Flushing was reported in subjects homozygous for ALDH2*2/*2 and heterozygous for ALDH2*1/*2, but not in those homozygous for ALDH2*1/*1[47]. Concerning polymorphisms of the CYP2E1 gene, subjects heterozygous for the promoter alleles C1/C2 or homozygous C2/C2 are better able to metabolize alcohol, which might increase free radical generation and lipid peroxidation, and promote fatty change in the liver[9]. Recently, the isoleucine-to-methionine substitution at position 148 (rs738409 C>G) in the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 protein (PNPLA3) has been reported to have a strong association with progression of alcoholic liver disease (including cirrhosis and HCC), as well as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[48,49]. Polymorphisms in CD14[50] or TNF-α[51] are reported to be associated with alcoholic liver injury, but further validation is needed.

Table 3.

Genetic polymorphisms associated with increased risk of alcoholic liver disease progression

| Gene | Polymorphism | Reported association | Ref. |

| ADH | ADH2*1/*2 | Decrease the rate of ethanol metabolism | [47] |

| ADH2*1/*1 | |||

| ALDH | ALDH2*2/*2 | Increase alcohol sensitivity | [47] |

| ALDH2*1/*2 | |||

| CYP2E1 | C1/C2 | Increase free radical generation, lipid peroxidation, and fatty change | [9] |

| C2/C2 | |||

| PNPLA3 | rs738409C>G | Increase the risk of liver cirrhosis and HCC | [48,49] |

| CD14 | 159TT | Enhance inflammatory responses | [50] |

| Develop alcoholic liver disease | |||

| TNF-α | 238G>A | Develop alcoholic liver disease | [51] |

ADH: Alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH: Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; CYP2E1: Cytochrome P450 2E1; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PNPLA3: Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Regarding HBV, a number of cohort studies have shown that some single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the HLA-DP loci are associated with persistent HBV infection. As shown in Table 4, for example, rs3077 SNP near the HLA-DPA1 gene and rs9277535 SNP near the HLA-DPB1 gene were associated with persistent HBV infection in Asian populations[52]. Among Chinese, Li et al[53] identified locus at 8p21.3 (index SNP rs7000921) contributing to the susceptibility to persistent HBV infection. They further demonstrated the nearby gene integrator complex subunit 10 at 8p21.3 suppresses HBV replication in an interferon regulatory factor 3-dependent manner in vitro and identified an antiviral gene integrator complex subunit 10 (INTS10) at 8p21.3 as involved in the clearance of HBV infection. A SNP near the IL-28B gene is associated with pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin treatment-induced/spontaneous viral clearance in chronic/acute HCV infection. In contrast, in chronic hepatitis B, previous studies yielded conflicting results of the association of IL-28B with response to interferon-α treatment or long-term outcome[54].

Table 4.

Genetic polymorphisms associated with hepatitis B virus infection

| Gene | Polymorphism | Reported association | Ref. |

| HLA-DPA1 | rs3077 CC | Persistent HBV infection | [52] |

| HLA-DPB1 | rs9277535 GG | Persistent HBV infection | [52] |

| INTS10 | rs7000921 TT or CC | Suppress HBV replication | [53] |

| Associated with clearance of HBV infection |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen; INTS10: Integrator complex subunit 10.

OTHER POSSIBLE FACTORS AFFECTING DISEASE PROGRESSION

Other factors may affect the progression of alcoholic liver injury, including the disease duration, patient sex, ethnicity and obesity[9,55,56]. Since longer duration of persistent alcohol intake is associated with disease progression in patients with alcoholic liver injury, it is generally accepted that strict abstinence must be recommended. Although a retrospective case-control study unexpectedly indicated that former drinkers who had stopped 1-10 years previously had a higher risk of HCC than current drinkers, the authors speculated the reason might be that many patients with HCC had stopped drinking some years prior to the study[30]. With regard to sex differences, women are more susceptible than men to the toxic effects of alcohol, as they have a significantly higher risk of developing progressive disease for any given level of alcohol intake[57]. In contrast, male patients with HBV are at higher risk of HCC than are female patients[58]. Previous studies on racial and ethnic differences have found that Hispanic, Black, and Asian subjects are more susceptible to alcohol-related liver damage than are Caucasians[59,60]. Additionally, in most Asian countries, genotype C is the most prevalent type of HBV, which is associated with an increased risk of disease progression[61]. As most large-scale clinical studies of HBV have been conducted in East Asia, it remains to be elucidated whether the obtained results can be applied to other areas, such as the United States and Europe. Lastly, Loomba et al[62] reported that alcohol and obesity synergistically increased the risk of HCC in 2260 HBsAg-positive men from the REVEAL-HBV study cohort (HR = 3.40; 95%CI: 1.24-9.34).

CONCLUSION

The association of light-to-moderate alcohol consumption with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic HBV infection appears modest, with a 1.5-fold increased risk at best, probably smaller than that of viral factors such as HBV DNA load and genotype. However, heavy alcohol consumption significantly accelerates the progression of liver disease to cirrhosis and, finally, HCC, with a 1.3-fold to 8.4-fold increased risk. As the mechanisms by which alcohol enhances disease progression are less well understood in patients with chronic hepatitis B than C, more experimental studies are warranted. In addition, alcohol abuse could impair the response to interferon-α therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B (as with C), although this is still controversial, and can increase the risk of HCC in patients with low HBV DNA levels suppressed by nucleoside/nucleotide therapy. Although the threshold amount of alcohol for HCC risk remains unknown, heavy alcohol intake is clearly associated with the progression of liver disease. Strict abstinence should be recommended in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: Professor Norifumi Kawada has received grants from Bristol-Myers K.K. and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Peer-review started: November 16, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Article in press: March 2, 2017

P- Reviewer: Eyre NS, Kasprzak A, Wongkajornsilp A S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Hepatitis B [Fact sheet]. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asselah T, Boyer N, Saadoun D, Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P. Direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: optimizing current IFN-free treatment and future perspectives. Liver Int. 2016;36 Suppl 1:47–57. doi: 10.1111/liv.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamori A, Enomoto M, Kawada N. Recent Advances in Antiviral Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6841628. doi: 10.1155/2016/6841628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabiri M, Jazwinski AB, Roberts MS, Schaefer AJ, Chhatwal J. The changing burden of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: model-based predictions. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:170–180. doi: 10.7326/M14-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Accessed October 11; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torok NJ. Update on Alcoholic Hepatitis. Biomolecules. 2015;5:2978–2986. doi: 10.3390/biom5042978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gramenzi A, Caputo F, Biselli M, Kuria F, Loggi E, Andreone P, Bernardi M. Review article: alcoholic liver disease--pathophysiological aspects and risk factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suhail M, Abdel-Hafiz H, Ali A, Fatima K, Damanhouri GA, Azhar E, Chaudhary AG, Qadri I. Potential mechanisms of hepatitis B virus induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12462–12472. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gitto S, Vitale G, Villa E, Andreone P. Update on Alcohol and Viral Hepatitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:228–233. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin J, Clayton MM, Liu J, Feitelson MA. Chronic ethanol consumption stimulates hepatitis B virus gene expression and replication in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:792–797. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min BY, Kim NY, Jang ES, Shin CM, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, et al. Ethanol potentiates hepatitis B virus replication through oxidative stress-dependent and -independent transcriptional activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha HL, Shin HJ, Feitelson MA, Yu DY. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in hepatic pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6035–6043. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i48.6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geissler M, Gesien A, Wands JR. Chronic ethanol effects on cellular immune responses to hepatitis B virus envelope protein: an immunologic mechanism for induction of persistent viral infection in alcoholics. Hepatology. 1997;26:764–770. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novo-Veleiro I, Alvela-Suárez L, Chamorro AJ, González-Sarmiento R, Laso FJ, Marcos M. Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1411–1420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Punzalan CS, Bukong TN, Szabo G. Alcoholic hepatitis and HCV interactions in the modulation of liver disease. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:769–776. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siu L, Foont J, Wands JR. Hepatitis C virus and alcohol. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:188–199. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima W, Tanaka T, Ohfuji S, Habu D, Tamori A, Kawada N, Sakaguchi H, Takeda T, Nishiguchi S, Seki S, et al. Does alcohol increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C virus infection? Hepatol Res. 2006;34:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678–686. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Su TH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Kuo SF, Liu CH, Chen PJ, Chen DS, et al. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low HBV load. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1140–1149.e3; quiz e13-14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LY, You SL, Lu SN, Ho HC, Wu MH, Sun CA, Yang HI, Chien-Jen C. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and habits of alcohol drinking, betel quid chewing and cigarette smoking: a cohort of 2416 HBsAg-seropositive and 9421 HBsAg-seronegative male residents in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:241–250. doi: 10.1023/a:1023636619477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jee SH, Ohrr H, Sull JW, Samet JM. Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, hepatitis B, and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1851–1856. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CJ, Yang HI. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B REVEALed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:628–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang HI, Yuen MF, Chan HL, Han KH, Chen PJ, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Chen CJ, Wong VW, Seto WK. Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B (REACH-B): development and validation of a predictive score. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:568–574. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, Fung J, Wong DK, Yuen JC, But DY, Chan AO, Wong BC, Mizokami M, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong VW, Chan SL, Mo F, Chan TC, Loong HH, Wong GL, Lui YY, Chan AT, Sung JJ, Yeo W, et al. Clinical scoring system to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1660–1665. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Medicines Agency (EMEA) (2010): Guideline on the development of medicinal products for the treatment of alcohol dependence. EMEA/CHMP/EWP/20097/2008. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/03/WC500074898.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, Parrinello G, Boffetta P, Albertini A, Decarli A, Trevisi P, Ribero ML, Martelli C, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:323–331. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin CW, Lin CC, Mo LR, Chang CY, Perng DS, Hsu CC, Lo GH, Chen YS, Yen YC, Hu JT, et al. Heavy alcohol consumption increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, Tsubota A, Koida I, Arase Y, Fukuda M, Chayama K, Murashima N, et al. Disease progression and hepatocellular carcinogenesis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis: a prospective observation of 2215 patients. J Hepatol. 1998;28:930–938. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribes J, Clèries R, Rubió A, Hernández JM, Mazzara R, Madoz P, Casanovas T, Casanova A, Gallen M, Rodríguez C, et al. Cofactors associated with liver disease mortality in an HBsAg-positive Mediterranean cohort: 20 years of follow-up. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:687–694. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buster EH, Hansen BE, Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Zeuzem S, Steyerberg EW, Janssen HL. Factors that predict response of patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B to peginterferon-alfa. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:2002–2009. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mochida S, Ohnishi K, Matsuo S, Kakihara K, Fujiwara K. Effect of alcohol intake on the efficacy of interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C as evaluated by multivariate logistic regression analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:371A–377A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohnishi K, Matsuo S, Matsutani K, Itahashi M, Kakihara K, Suzuki K, Ito S, Fujiwara K. Interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C in habitual drinkers: comparison with chronic hepatitis C in infrequent drinkers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1374–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen VA, Gao B. Expression of interferon alfa signaling components in human alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:425–432. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Bona D, Cippitelli M, Fionda C, Cammà C, Licata A, Santoni A, Craxì A. Oxidative stress inhibits IFN-alpha-induced antiviral gene expression by blocking the JAK-STAT pathway. J Hepatol. 2006;45:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrillo RP, Lai CL, Liaw YF, Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Schalm SW, Heathcote EJ, Brown NA, Atkins M, Woessner M, et al. Predictors of HBeAg loss after lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2002;36:186–194. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung WG, Kim HJ, Choe YG, Seok HS, Chon CW, Cho YK, Kim BI, Koh YY. Clinical impacts of hazardous alcohol use and obesity on the outcome of entecavir therapy in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:195–202. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.26180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka F, Shiratori Y, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Tsukada Y, Omata M. Polymorphism of alcohol-metabolizing genes affects drinking behavior and alcoholic liver disease in Japanese men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:596–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salameh H, Raff E, Erwin A, Seth D, Nischalke HD, Falleti E, Burza MA, Leathert J, Romeo S, Molinaro A, et al. PNPLA3 Gene Polymorphism Is Associated With Predisposition to and Severity of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:846–856. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campos J, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Quinteiro C, Gude F, Perez LF, Torre JA, Vidal C. The -159C/T polymorphism in the promoter region of the CD14 gene is associated with advanced liver disease and higher serum levels of acute-phase proteins in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1206–1213. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171977.25531.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marcos M, Gómez-Munuera M, Pastor I, González-Sarmiento R, Laso FJ. Tumor necrosis factor polymorphisms and alcoholic liver disease: a HuGE review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:948–956. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamori A, Kawada N. HLA class II associated with outcomes of hepatitis B and C infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5395–5401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Si L, Zhai Y, Hu Y, Hu Z, Bei JX, Xie B, Ren Q, Cao P, Yang F, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 8p21.3 associated with persistent hepatitis B virus infection among Chinese. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11664. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stättermayer AF, Ferenci P. Effect of IL28B genotype on hepatitis B and C virus infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;14:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato N, Lindros KO, Baraona E, Ikejima K, Mezey E, Järveläinen HA, Ramchandani VA. Sex difference in alcohol-related organ injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:40S–45S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fattovich G. Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:47–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart SH. Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol-associated aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase elevation. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2236–2239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickramasinghe SN, Corridan B, Izaguirre J, Hasan R, Marjot DH. Ethnic differences in the biological consequences of alcohol abuse: a comparison between south Asian and European males. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30:675–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Enomoto M, Tamori A, Nishiguchi S. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and response to antiviral therapy. Clin Lab. 2006;52:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loomba R, Yang HI, Su J, Brenner D, Iloeje U, Chen CJ. Obesity and alcohol synergize to increase the risk of incident hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:891–898, 898.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]