Abstract

Gracilaria lemaneiformis (G. lemaneiformis) is rich in polysaccharides that have many functional activities. In this study, the thermostable α-amylase-assisted extraction and antioxidant activity of water-soluble polysaccharides from G. lemaneiformis were investigated. The extraction conditions were optimized as follows: time, 40 min; temperature, 95 °C; pH, 5 and enzyme amount, 6000 U/g, under which the yield of G. lemaneiformis polysaccharides (GPs) reached 49.15% dry base. The GPs were characterized by monosaccharide composition, FTIR spectrum, UV spectrum and antioxidant activities. The results indicate that the GPs had strong hydroxyl radical activity at a concentration of 100 μg/mL and could be used as potential antioxidants.

Keywords: Gracilaria lemaneiformis, Polysaccharides, Antioxidant activity, Thermostable α-amylase

Introduction

Gracilaria lemaneiformis (G. lemaneiformis) belongs to the family Gracilariaceae (Rhodophyta). Gracilaria lemaneiformis is widely distributed in the marine environment and one of the principal sources of agar (Fan et al. 2012a). At present, the mariculture of G. lemaneiformis is one of the leading industries in China due to its high adaptability, rapid growth and potential to improve the water environment (Li et al. 2008). Gracilaria lemaneiformis is one of the popular food resources in China due to its good flavour and rich nutrition: it contains 14.65% of sugar, 21% of protein, 0.87% of lipids and considerably high levels of vitamin C, iodine, phosphorus and zinc (Wen et al. 2006).

Gracilaria lemaneiformis is rich in polysaccharides, which has many biological activities such as anti-tumour, immunomodulatory and anti-influenza virus activities (Chen et al. 2010; Fan et al. 2012a, b), and therefore could be used in food and medical industries. However, the antioxidant activity of G. lemaneiformis polysaccharides (GPs) is not frequently reported.

Recently, studies on different methods for polysaccharide extraction from G. lemaneiformis had been developed, such as hot water, ultrasonic waves, ultrasonic-hot water, microwave-assisted extraction and citric acid (Liu et al. 2013; You et al. 2016; Yang and Zhuang 2011). Nevertheless, the data regarding enzymatic-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from G. lemaneiformis are limited.

In this study, water-soluble GPs were prepared from G. lemaneiformis by a thermostable α-amylase-assisted extraction procedure, during which the extraction conditions were optimized, the GPs were partially characterized and the antioxidant activity of GPs was investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fresh G. lemaneiformis was purchased from a local farmer market in Xinpu, China. The thermostable α-amylase from Thermococcus sp. HJ21, with an enzymatic activity of 20,000 U/g, was prepared in our laboratory according to the method described by Wang et al. (2009). Reagent-grade chemicals were used.

GP preparation

Fresh G. lemaneiformis was washed by tap water and dried in a hot air oven (JK-OOI-240A, China) at 60 °C until a constant weight was observed. The dried G. lemaneiformis was then pulverized and sifted through a 40-mesh sieve to obtain a fine powder with approximately 7% moisture content (dry basis) and stored in dark bags in a dry environment until use.

The dried G. lemaneiformis powder was lipid-removed with organic solvents (light petroleum, acetone and methanol) in a Soxhlet apparatus. After removing solvent by evaporation, the lipid-removed G. lemaneiformis powder was soaked in distilled water to give a suspension with a concentration at 2%. The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 3.5–6, and 2000–10,000 U/g of thermostable α-amylase was added. The reactor was maintained in a thermostatic water bath at 75–100 °C for 10–60 min and then the thermostable α-amylase was inactivated by incubating at 120 °C in a sterilizer for 10 min.

The extracts were filtered through a Whatman GF/A filter paper and concentrated to approximately 20%. The proteins were removed using the Sevag method (Sevag et al. 1938), and the extracts were precipitated with 5 volumes of absolute ethanol, filtered through a Whatman GF/A filter paper and freeze-dried. The yield of GPs was calculated using Eq. (1) as follows:

| 1 |

where W 1 and W 2 represent the weights of the recovered GPs and the original dried G. lemaneiformis powder, respectively.

Analytical methods

The pH of the reaction mixture was recorded using a digital pH meter (Model PHS-3C; CD Instruments, China). Ash, total sugar and protein contents were determined using the phenol–sulphuric acid colorimetric method, the Kjeldahl method and a method proposed by Hou (2004), respectively. The monosaccharide composition of the GP sample was analysed using the procedure reported by Sheng et al. (2007). The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the resulting GP sample were recorded in KBr pellets by a Nicolet Nexus FTIR 470 spectrophotometer (Thermo Nicolet, USA) over a wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1. The UV spectra were recorded on a UV spectrometer (Spectra Test, Germany).

Antioxidant activity assay

The hydroxyl radical (HO∙) scavenging activity (HRSA) of the GP sample was determined according to the method of Wu and Yu (2015). Briefly, 1 mL of 6 mM FeSO4 solution, 1 mL of 6 mM H2O2, 0.5 mL of 2 mM salicylic acid and 1 mL of sample solutions at various concentrations (20–120 mg/mL) were mixed well and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The absorbance of the mixture was then measured at 510 nm, and ascorbic acid was used as positive control. The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

| 2 |

where A 0 is the absorbance of the reagent blank absorbance, A 1 is the positive control absorbance and A 2 is the absorbance of the sample.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Statgraphics Centurion XV version 15.1.02. A multifactor ANOVA with posterior multiple range test was used for determining statistical significance.

Results and discussion

Effect of reaction time, temperature, pH and thermostable α-amylase amount on GP yield

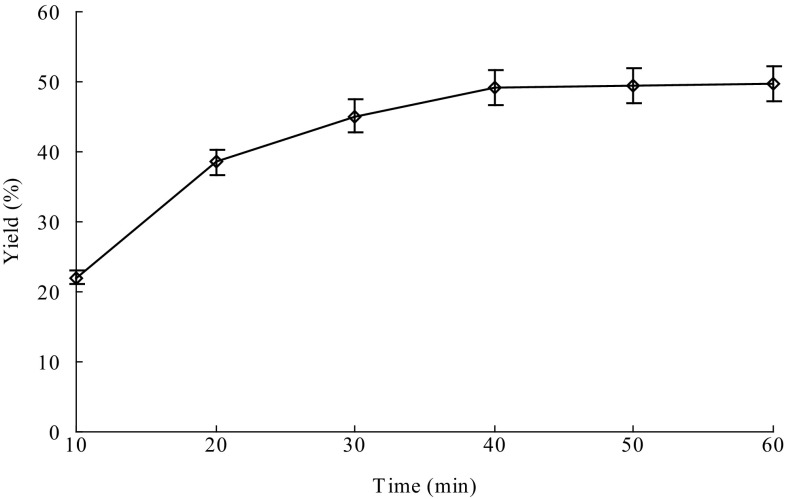

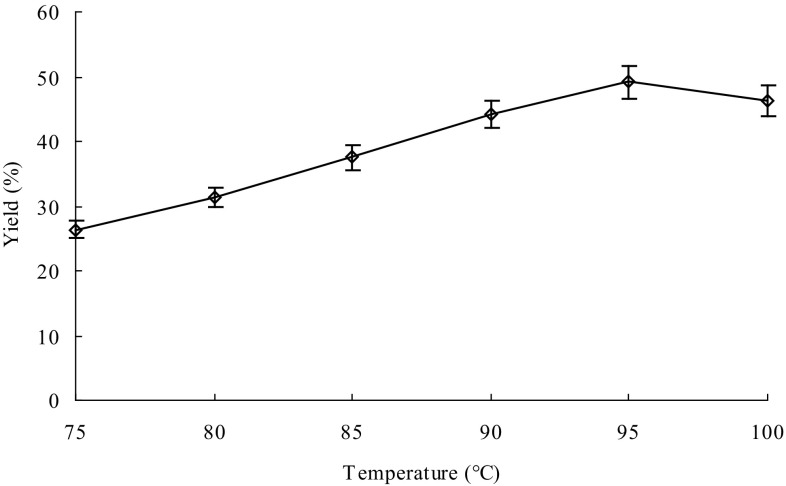

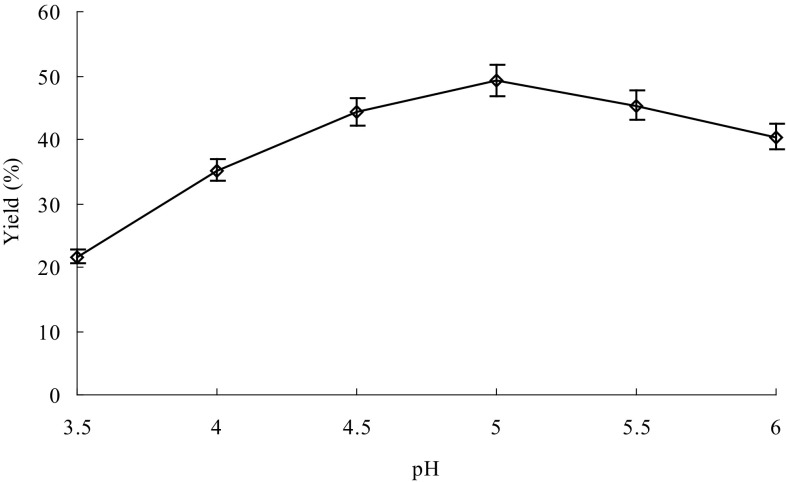

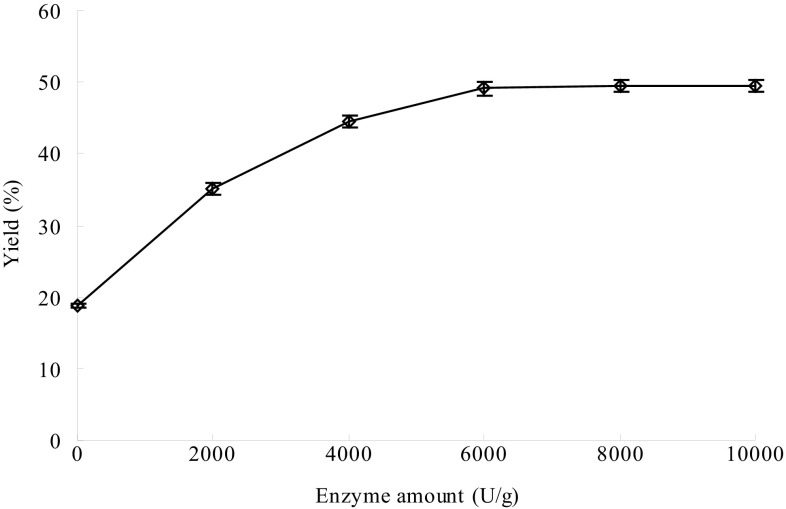

Reaction time, temperature and pH affect the thermostable α-amylase activity and thus are important for efficient extraction of the GPs. At the same time, the amount of thermostable α-amylase could also be important for efficient extraction of the GPs. Therefore, the effects of different reaction time, temperature, pH and thermostable α-amylase amount on extraction of the GPs were investigated for maximum yield of the GPs. The optimum reaction conditions were time 40 min (Fig. 1), 95 °C (Fig. 2), pH 5 (Fig. 3) and thermostable α-amylase amount of 4000 U/g (Fig. 4). In contrast, Wang et al. (2009) previously reported that the optimal conditions of thermostable α-amylase for hydrolysis of starch were 90 °C and pH 5.0. The difference in optimal reaction conditions could be due to the differences in substrates. Under the optimum reaction conditions, the yield of GPs reached up to 49.15%, which is higher than those of other extraction methods previously reported (Liu et al. 2013; You et al. 2016; Yang and Zhuang 2011).

Fig. 1.

Effect of reaction time on extraction of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides. Temperature, 95 °C; pH, 5 and enzyme amount, 6000 U/g. Bars represent the standard deviation. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 2.

Effect of temperature on extraction of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides. Reaction time, 40 min; pH, 5 and enzyme amount, 6000 U/g. Bars represent the standard deviation. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH on extraction of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides. Reaction time, 40 min; temperature, 95 °C; and enzyme amount, 6000 U/g. Bars represent the standard deviation. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 4.

Effect of thermostable α-amylase amount on extraction of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides. Reaction time, 40 min; temperature, 95 °C and pH, 5. Bars represent the standard deviation. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Product characterization

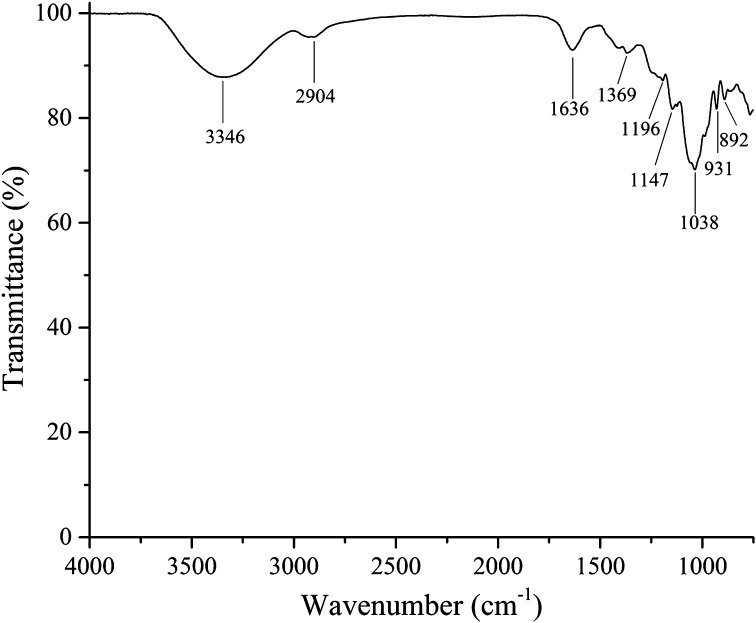

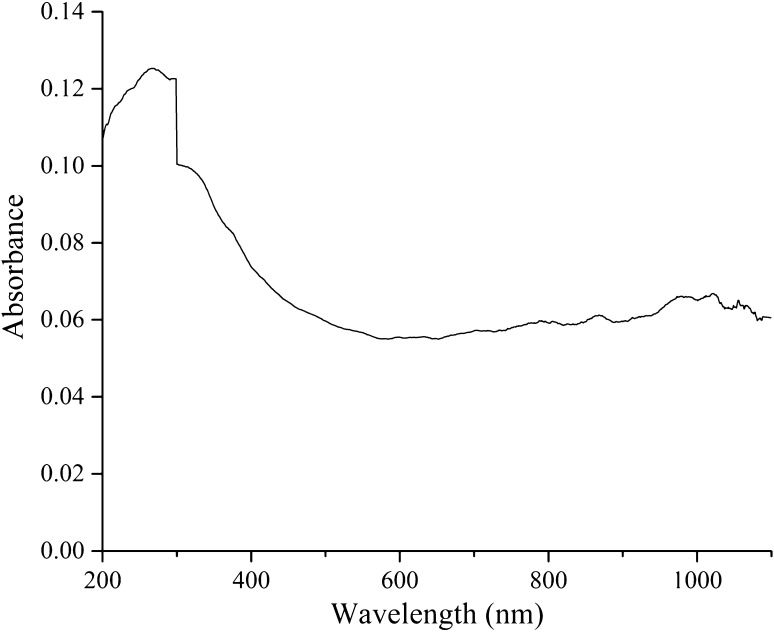

The ash, moisture, total sugar and protein contents of the GP samples were 1.7, 2.8, 91.4 and 0.7%, respectively. The product samples were water-soluble and showed light green. Sugar composition analysis of GPs by high-performance liquid chromatography showed that the polysaccharides consisted of rhamnose, arabinose, xylose and mannose, consistent with a previous report by Fan et al. (2012a). The FTIR spectra of the GPs sample showed peaks at 2904–3346 cm−1 (O–H, C–H), 1636 (bound water), 1369 cm−1 (symmetrical deformation of –CH3 and –CH2), 1196–1147 (special absorption peaks of the α (1 → 4) glucoside bond) and 1038–892 (sulfo groups) (Fig. 5), indicating that the GPs were polysaccharides containing α (1 → 4) glucoside bond and sulfo groups. The UV spectra of the GP sample displayed a peak at ~280 nm (Fig. 6), indicating that the GPs contained some protein and were consistent with the chemical composition analysis.

Fig. 5.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides

Fig. 6.

UV spectra of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides

Antioxidant activity of GPs

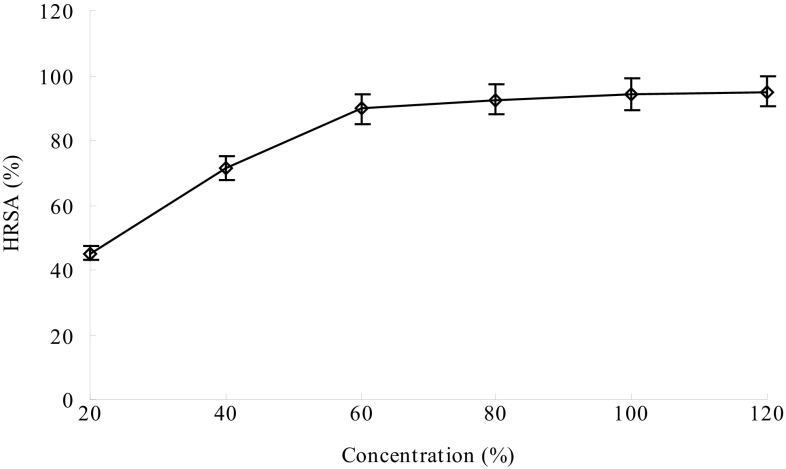

HO∙ has the highest activity among the reactive oxygen species, inducing severe damage to biomolecules and causing oxidative injury to biomolecules, such as lipids, proteins, carbohydrate and DNA. Therefore, HO∙ has been widely accepted as a tool for evaluating free radical scavenging antioxidant activity (Qiao et al. 2009). The HRSA of GPs is presented in Fig. 7. At the concentration of 120 mg/mL, the HRSA reached up to 95.07%. These results indicate that the GPs have the ability to scavenge HO∙. The antioxidant activity of GPs could be ascribed to the fact that the GPs can donate electrons to the reactive groups, by reducing them to more stable and non-reactive species.

Fig. 7.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (HRSA) of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharides

Conclusions

In the present study, thermostable α-amylase-assisted extraction of water-soluble GPs was performed. The GP yield was affected by extraction time, temperature, pH and the amount of thermostable α-amylase. Partial characterization and antioxidant activity of the GPs were performed. This study provides important information for the extraction of GPs which could be used as functional food with antioxidant activities.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471719), the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu (Social Development, BE2016702) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Chen MZ, Xie HG, Yang LW, Liao ZH, Yu J. In vitro anti-influenza virus activities of sulfated polysaccharide fractions from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Viro Sin. 2010;25:341–351. doi: 10.1007/s12250-010-3137-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YL, Wang WH, Song W, Chen HS, Teng AG, Liu AJ. Partial characterization and anti-tumor activity of an acidic polysaccharide from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;88:1313–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Wang W, Chen H, Liu N, Liu A. In vitro and in vivo immunomodulatory activities of an acidic polysaccharide from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Adv Mater Res. 2012;468–471:941–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Hou ML. Food analysis. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li HY, Yu XJ, Jin Y, Zhang W, Liu YL. Development of an eco-friendly agar extraction technique from the red seaweed Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:3301–3305. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MQ, Yang XQ, Qi B, Li LH, Deng JC, Hu X. Study of ultrasonic-freeze-thaw-cycle assisted extraction of polysaccharide and phycobiliprotein from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Adv Mater Res. 2013;781-784:1818–1824. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.781-784.1818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao DL, Ke CL, Hu B, Luo JG, Ye H, Sun Y, Yan XY, Zeng XX. Antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Hyriopsis cumingii. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;78:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sevag MG, Lackman DB, Smolens J. Isolation of components of Streptococcal nucleoproteins in serologically active form. J Biol Chem. 1938;124:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J, Yu F, Xin Z, Zhao L, Zhu X, Hu Q. Preparation, identification and their antitumor activities in vitro of polysaccharides from Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Food Chem. 2007;105:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SJ, Lu ZX, Qin S, Lu MS, Li FC, Liu HF, Dun XY. Production and characterization of thermostable and acid-stable α-amylase from hyperthermophilic archaeon thermococcus SP. Oceanol Et Limnol Sinaca. 2009;40:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Peng C, Zhou H, Lin Z, Lin G, Chen S, Li P. Nutritional composition and assessment of Gracilaria lemaneiformis Bory. J Integr Plant Biol. 2006;48:1047–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SJ, Yu L. Preparation and characterization of the oligosaccharides derived from Chinese water chestnut polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2015;181:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Zhuang CF. Gracilaria lamaneiformis polysaccharides: optimization of microwave-assisted extraction by response surface methodology and antioxidant properties. Food Sci. 2011;32:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- You LJ, Zhang YL, Wen LR, Liu RH, Fu X. Effect of extraction method on the properties of polysaccharides from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Mod Food Sci Technol. 2016;32(148–155):182. [Google Scholar]