Abstract

Aim

This study represents an enumeration and comparison of gross target volumes (GTV) as delineated independently on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and T1 and T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in vestibular schwannomas (VS).

Background

Multiple imaging in radiotherapy improves target localization.

Methods and materials

42 patients of VS were considered for this prospective study with one patient showing bilateral tumor. The GTV was delineated separately on CT and MRI. Difference in volumes were estimated individually for all the 43 lesions and similarity was studied between CT and T1 and T2 weighted MRI.

Results

The male to female ratio for VS was found to be 1:1.3. The tumor was right sided in 34.9% and left sided in 65.1%. Tumor volumes (TV) on CT image sets were ranging from 0.251 cc to 27.27 cc. The TV for CT, MRI T1 and T2 weighted were 5.15 ± 5.2 cc, 5.8 ± 6.23 cc, and 5.9 ± 6.13 cc, respectively. Compared to MRI, CT underestimated the volumes. The mean dice coefficient between CT versus T1 and CT versus T2 was estimated to be 68.85 ± 18.3 and 66.68 ± 20.3, respectively. The percentage of volume difference between CT and MRI (%VD: mean ± SD for T1; 28.84 ± 15.0, T2; 35.74 ± 16.3) and volume error (%VE: T1; 18.77 ± 10.1, T2; 23.17 ± 13.93) were found to be significant, taking the CT volumes as the baseline.

Conclusions

MRI with multiple sequences should be incorporated for tumor volume delineation and they provide a clear boundary between the tumor and normal tissue with critical structures nearby.

Keywords: Vestibular schwannomas (VS), Computed tomography (CT), T1 weighted and T2 weighted, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

1. Background

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT) were introduced as an alternate treatment modality to surgery for patients who are not fit for surgical procedures and to avoid post surgical complications.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The main aim of SRS and SRT is to reduce the dose to surrounding normal tissue and nearby critical structures while ensuring a very high prescribed dose to the target volume either through single fraction or by hypo-fractionation treatment schemes.9, 10 The primary imaging modality utilized in the process of radiotherapy treatment planning is computed tomography (CT) which provides a valuable electron density information essential for dose calculations. Accuracy in target volume delineation plays a crucial role in radiotherapy planning of intracranial tumors. The intracranial target volume is defined as the gross tumor volume (GTV) on CT images. However, the CT alone does not offer sufficient information because of its intrinsic limitations in distinguishing between normal soft tissues and tumor tissues. Hence, different imaging modalities need to be utilized for broader understanding of the situation and to distinguish the boundary between the GTV and normal tissue for delineation of the tumor. Thus, a proper multimodality11, 12, 13, 14 imaging technique should be adopted to extract information required for the correct delineation of GTV. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)15, 16 seems to be a good choice for the delineation of GTV in skull based tumors in the brain due to its superiority in distinguishing soft tissue contrast.

Tumors that originate in the cerebello pontine (CP) angle of the intracranial region are called cerebello pontine angle tumors.17, 18, 19, 20 About 10% of brain tumors either originate from or involve the CP angle. About 80% of CP angle tumors are cases of vestibular schwannomas (VS)21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and the remaining ones are non-acoustic tumors like meningiomas and epidermoids. The vestibular schwannomas are also known as acoustic neuromas (AN). The VS are benign tumors that arise due to the uncontrolled growth of Schwann cells which myelinate (insulating sheath) around the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve.

2. Aim

The purpose of this study was to compare the differences in target volume when the GTV is contoured separately on CT and sequencely acquired MRI images by the method of blind view. This study was undertaken to justify the importance of the multimodality imaging technique in the case of vestibular schwannomas.

3. Methods and materials

160 patients with brain tumor were treated by SRS and SRT using 6 MV X-rays from Varian Novalis Tx (Varian Medical System, USA) medical electron linear accelerator at our institution from 2010 to 2015. 43 out of the 160 patients were proven cases of vestibular schwannomas and hence these patients were selected for this study. The brain mask was used for immobilization and contrast-enhanced CT images were acquired with a cast in situ. T1- and T2-weighted MRI images of these patients were also acquired. The Brain LAB iplan (AG, Feldkirchen, Germany) radiotherapy treatment planning system (TPS) was used to obtain the dose distributions.

3.1. Patient set up

A noninvasive immobilization setup for the brain is provided by the Brain LAB (AG, Feldkirchen, Germany). The system consists of a two-part mask, one fitted to the back and the other to the front side of the brain with additional mouth bite to maintain the head position. The Brain LAB localizer box was also used during the scan so that stereotactic coordinates can be generated in the Brain LAB iPlan TPS. A complete description of the Brain LAB immobilization and localizer box is available elsewhere.26

3.2. CT imaging

The CT was used as a primary imaging modality in this study. For acquiring the CT images, the patients were immobilized using Brain LAB stereotactic head immobilization mask and CT localizer on the flat couch of the 16 slice Philips Brilliance CT scanner [Big Bore Oncology unit with 85 cm bore and 60 cm field of view (FOV)]. Axial cuts were taken from the vertex to the base of the skull with a matrix size of 512 × 512. Contrast enhanced CT images were also acquired. The images were reconstructed with 2 mm slice thickness. The images so acquired were transferred to the Brain LAB iPlan TPS workstation through the DICOM system.

3.3. MR imaging

The MRI was used as a floating imaging modality in this study. MRI scans were taken with the standard head coil (1.5 T, General Electric Medical System sigma HD). The images from the vertex to the base of the skull were obtained with a spin-echo (SE) sequence. The conventional turbo spin-echo T2-weighted plain and post-gadolinium contrast T1-weighted spin-spin echo axial MR images were obtained using a 254 × 254 matrix, 31.25 Hz/pixel bandwidth and 250 mm FOV. The MR images were transferred to the Brain LAB iPlan TPS workstation through the DICOM system.

3.4. Image registration

Nowadays, all the commercially available TPS have the multimodality image registration facility. Using this option of our Brain LAB iPlan TPS, the CT images were fused with the MRI images. The Brain LAB iPlan TPS uses a powerful, automated and accurate registration method.27 The image registration is a two-step method with coarse and fine adjustments. It is a mutual information similarity based rigid registration technique which increases the efficiency of matching with less time. So, for all the 43 cases of VS, CT images were registered with MRI.

3.5. GTV delineation

A single radiation oncologist (RO) performed target delineation independently on the CT images as well as on T1- and T2-weighted MR images as shown in Fig. 1. The RO contoured the target volume, brainstem, right cochlea and left cochlea on CT, T1- and T2-weighted image sets independently by hiding another image sets to avoid biasing. ICRU-5028 guidelines were followed during the contouring process. One of the patients identified with bilateral occurrence of VS was treated as an independent case in this study. The GTVs were first contoured on contrast enhanced CT images and then on T1- and T2-weighted MR image sets separately and, finally, all the images were connected to each other. Following steps were taken for delineation of GTV on CT and MRI images: The gross target volume was marked on T1-weighted MR images (named as GTVT1-MRI) and T2-weighted MR images (named as GTVT2-MRI). The CT images were adjusted suitably (by varying the window level, window widths and gray scale) to bring clarity in visualization of all the organs and tissues so that best possible GTV can be delineated. The final GTV was expanded to them in all tumors in CT + T1-MRI and CT + T2-MRI and a union of all the three tumor contours were clubbed as CT + T1-MRI + T2-MRI images to obtain the three different volumes. A comparison of CT volume and MRI volumes were done for all the target volumes.

Fig. 1.

Gross tumor volume (GTV) of a left vestibular schwannoma patient contoured on (a) CT image, (b) T1-weighted MR image, and (c) T2-weighted MR image.

3.6. Statistical analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the segmentation procedure on the two modalities we used the similarity measures usually utilized in image processing between a true value and a measured value. To find out the percentage of overlap of target volumes contoured separately on two image sets, Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC)29, 30, 31 was used, which is defined as

| (1) |

where VCT and VMRI are the target volumes contoured on CT and MRI images respectively.

The percentage of volume difference (%VD) between the CT and MRI segmented target volumes were estimated using the following relation

| (2) |

The raw data required for evaluating %DSC and %VD was entered in to a statistical excel sheet and statistical analysis was performed to evaluate a mean, standard deviation and statistical significance. The statistical significance was less than 0.05 (p < 0.05). The correlation between CT and MRI segmented volumes were compared by using Pearson's coefficients. The percentage volume error (VE) was estimated using the following equation

| (3) |

In addition, the volume conformity index (VCI) was also calculated by taking ratio of common volume between CT and MRI to the CT volume.

4. Results

160 patients of various brain tumor cases were treated on Varian Novalis Tx medical electron linear accelerator of our institute from 2010 to 2105. Table 1 presents the details of the 43 patients included in this study. The mean age of male and female patients with vestibular schawnnomas was 36.28 and 41.5 years, respectively. The left sided to right sided VS tumor ratio was 65.1% and 34.9%, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the incidence of VS according to the age group and size of the GTV.

Table 1.

Summary of vestibular schawnnoma patients included in this study.

| N− = 43 | Right-VS | Left-VS | Mean age (yrs) | Std | Median age | Minimum age | Maximum age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 7 | 17 | 36.28 | 10.98 | 36 | 16 | 54 |

| Male | 8 | 11 | 41.53 | 15.84 | 38 | 19 | 62 |

Table 2.

Groups of vestibular schawnnoma patients with respect to age and gross tumor volume (cc).

| Age in years |

GTV in cc |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=20 | 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | <3 cc | 3 cc–5 cc | 5 cc–10 cc | >10 cc | |

| No of patients | 4 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 19 | 10 | 10 | 4 |

| Percentage | 9.3 | 25.6 | 23.3 | 20.9 | 14.0 | 7.0 | 44.2 | 23.6 | 23.6 | 8.6 |

Table 3 presents summary of gross tumor volume, brainstem, right cochlea and left cochlea recorded from contours on CT and T1- and T2-weighted MR image sets. The mean, maximum, and minimum values of GTV as well as its standard deviation are also indicated in this table.

Table 3.

Summary of gross tumor volume, brainstem, right cochlea and left cochlea recorded from contours on computed tomography (CT) as well as T1- and T2-wighted magnetic resonance (MR) image sets (N: number of patients, SD: standard deviation, CI: 95% confidence interval).

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | Pair test | N | Pearson's r | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTV_’CT | 43 | 5.152 | 5.253 | 0.251 | 3.484 | 27.266 | GTV_’CT, T1 | 43 | 0.971 | 0.945–0.985 | <0.0001 |

| GTV_’T1 | 43 | 5.876 | 6.166 | 0.385 | 4.196 | 36.231 | GTV_’CT, T2 | 43 | 0.973 | 0.949–0.986 | <0.0001 |

| GTV_’T2 | 43 | 5.637 | 5.976 | 0.378 | 4.53 | 35.101 | GTV_’T1, T2 | 43 | 0.995 | 0.991–0.998 | <0.0001 |

| Brain Stem: CT | 43 | 19.157 | 3.461 | 14.36 | 18.66 | 25.12 | Brain Stem: CT, Brain Stem: T1 | 43 | 0.894 | 0.811–0.941 | <0.0001 |

| Brain Stem: T1 | 43 | 20.253 | 4.473 | 15.99 | 18.48 | 31.5 | Brain Stem: CT, Brain Stem: T2 | 43 | 0.957 | 0.922–0.977 | <0.0001 |

| Brain Stem: T2 | 43 | 19.265 | 4.48 | 13.88 | 18 | 28.93 | Brain Stem: T1, Brain Stem: T2 | 43 | 0.85 | 0.739–0.917 | <0.0001 |

| Rt Cochlea: CT | 43 | 0.152 | 0.057 | 0.04 | 0.142 | 0.277 | Rt Cochlea: CT, Rt Cochlea:T1 | 43 | 0.381 | 0.091–0.612 | 0.0116 |

| Rt Cochlea: T1 | 43 | 0.147 | 0.051 | 0.052 | 0.152 | 0.235 | Rt Cochlea: CT, Rt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.696 | 0.5–0.824 | <0.0001 |

| Rt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.239 | 0.111 | 0.083 | 0.205 | 0.506 | Rt Cochlea: T1, Rt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.597 | 0.36–10.761 | <0.0001 |

| Lt Cochlea: CT | 43 | 0.152 | 0.045 | 0.082 | 0.163 | 0.246 | Lt Cochlea: CT, Lt Cochlea: T1 | 43 | 0.752 | 0.583–0.858 | <0.0001 |

| Lt Cochlea: T1 | 43 | 0.135 | 0.042 | 0.067 | 0.127 | 0.199 | Lt Cochlea: CT, Lt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.772 | 0.614–0.871 | <0.0001 |

| Lt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.221 | 0.101 | 0.089 | 0.19 | 0.514 | Lt Cochlea: T1, Lt Cochlea: T2 | 43 | 0.478 | 0.207–0.680 | 0.0012 |

Table 4 shows the mean values of VD, VE and DSC estimated for T1- and T2-weighted MR images as well as for T1 + T2 MR images. The DSCs assessed for T1- and T2-weighed MR images are 68.9% and 66.7%, respectively. Thus, the tumor volumes obtained from T1-weighted MR images have a relatively high conformity (i.e. overlapping) with the tumor volume obtained from the CT images in comparison to overlapping of tumor volumes from T2-weighted MR image with the tumor volume from CT images. The minimum and maximum DSC values were in the range of 48.3%–90.4% for T1-weighted MR images and 34.61%–87.94% for T2-weighted MR images, respectively. A relation between the absolute volume difference in cc and dice coefficients against the tumor volume was evaluated as shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Mean percentage values of volume difference (%VD), percentage of volume error (%VE) and dice similarity coefficient (DSC) estimated for T1- and T2-weighted MR images as well as T1 + T2 MR images. Data of CT image was taken as reference for calculating %VD, %VE and %DSC.

| Image | %VD | %VE | %DSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 28.84 (±15.02) | 18.77 (±10.1) | 68.9 (±18.3) |

| T2 | 35.74 (±16.3) | 23.17 (±13.9) | 66.7 (±20.3) |

| T1 + T2 | 35.72 (±18.3) | 54.87 (±48.1) | – |

Fig. 2.

Plot showing dice coefficient (DSC) on the primary axis of ordinate for the T1- and T2-weighted MR images and the difference in volume between the CT and MR images on the secondary axis of the ordinate versus the tumor volume on CT.

The correlation between the volumes of GTV, brainstem, right cochlea and left cochlea recorded from CT images and T1-weighted MR images as well as CT images and T2-weighted MR images are shown in Fig. 3. These data have also been summarized in Table 3. The difference in r values between CT estimated versus T1-MR estimated and the CT estimated versus T2-MR estimated are not very significant and the volumes obtained from these images are positively correlated. However, the tumor volumes recorded from T1- and T2-weighted MR images are higher than the tumor volumes recorded from CT images with p value <0.0001.

Fig. 3.

Scatter diagram of GTVs recorded from (a) CT images and T1-weighted MR images, and (b) CT images and T2-weighted MR images demonstrating the correlation between the CT recorded and MR recorded GTVs.

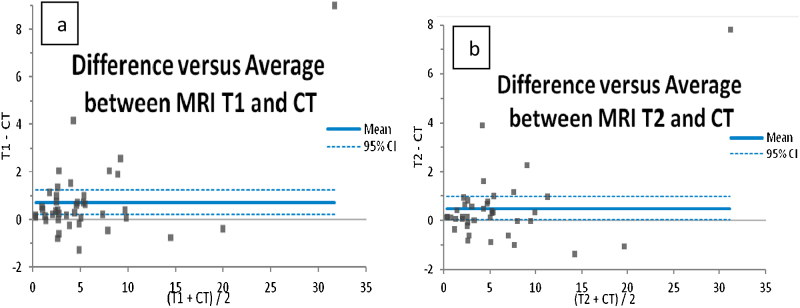

Fig. 4 shows Bland–Altman plot between difference in GTVs of CT and T1-weighted MR images [GTVT1-MRI − GTVCT] and average GTV of CT and T1-weighed MR images [(GTVT1 − MRI + GTVCT)/2] as well as difference in GTVs of CT and T2-weighted MR images [GTVT1-MRI − GTVCT] and average GTV of CT and T2-weighted MR images [(GTVT1 − MRI + GTVCT)/2]. This plot was generated to assess the agreement between the GTVs recorded from CT and MR images. It is observed that the volumes recorded from the T1-weighted MR images are larger than the volumes recorded from the CT images. The mean difference between GTVCT and GTVT1-MRI is 0.72 cc while the mean difference between GTVCT and GTVT2-MRI is 0.5 cc.

Fig. 4.

Bland–Altman plot between (a) difference in GTVs of CT and T1-MR images [GTVT1-MRI − GTVCT] and average GTV of CT and T1-MR images [(GTVT1-MRI + GTVCT)/2], and (b) difference in GTVs of CT and T2-MR images [GTVT1-MRI − GTVCT] and average GTV of CT and T2-MR images [(GTVT1-MRI + GTVCT)/2]. The data in these figures are in cc.

Fig. 5 shows variation in volume conformity index with respect to GTV volume (cc) recorded from the CT image. The VCI of T1-and T2-weighted MR images are shown in this curve. The mean VCI of T1-MR and T2-MR images are found to be 0.8 and 0.72, respectively.

Fig. 5.

A schematic diagram of volume conformity index for T1 and T2 with respect to CT.

5. Discussion

MRI provides superior information on anatomy and the pathology in clinical evaluation of the tumor size and boundary between the normal tissue and tumor tissue. There is an increasing demand in radiotherapy to segment tumor volumes with different imaging modality and compare them by similarity overlap coefficients.31 What is the best way to obtain the tissue and target volumes comparable to true volumes is still the topic of investigation. It is indeed difficult to estimate the tumor volume accurately from the CT images and till the date there exists no absolute technique. Practically, there is a change in volume of tissues whether it is alive or dead. The segmentation of volume depends on a number of parameters including reproducibility of patient positioning on multiple imaging modalities, inherent noise, registration technique and the calculation algorithm used for estimating volumes by treatment planning systems.32 In addition, there is inter and intra observer variability in contouring and delineation of tumor. Thus, the estimated volume is a combination of all these errors which are inherent and not very easy to be calculated separately.

A number of studies have been conducted33, 34, 35, 36, 37 on the tumor volume comparison for CT in conjunction with MRI for brain lesions like inter observer variations, impact of image registration of MR pre-operative and post-operative images on treatment planning CT scans.

In our study on the 43 cases, the relative numbers of female and male patients was 55.8% and 44.2%, respectively, showing a clear dominance of female patients which is in agreement with the observations of Ozgen et al.38, 39, 40 and van de Langerberg et al.41 However, our data indicates a relatively higher incidence of left sided VS over right sided VS. In our analysis of age, the number of relatively young patients is 25.6% which is larger than the number of other age groups. Out of 43 cases treated at our institution, the percentage of post operative radiotherapy, radical radiotherapy and recurrence cases were 25.6, 69.8 and 4.6, respectively. In Bland–Altman plot we observed the two high outliers with the volumes of 20.18 cc and 27.27 cc. These two cases are the recurrence cases. Further, 11 cases with post surgical volume showed above 95% CI limit.

The appearance of VS tumor on CT is iso-intense and the introduction of contrast enhances the visibility of the lesion. But there is a lack of knowledge on how to distinguish the boundary between the tumor and brain tissue from such images. The VS appears hypo-intense on T1-weighted MR image and hyper-intense on T2-weighted MR images.38 A lot of works have been reported to deal with the adequacy treatment modalities for managing VS including surgery and radiotherapy. Many of these works have reported the increase in tumor volume of VS on yearly basis.

Rykaczewski et al.42 have done meta analysis on treatment of VS treated by gamma knife. They compared treatment results of two set of VS patients one set treated during 1998–2007 and the other during 2007–2011. Their study includes 3233 VS patients having mean tumor volume of 3.9 cc and the control rate of 92.73%. Apicella et al.43 presented a thorough review of the literature and concluded that SRS is suitable for small size lesions.

Miller et al.44 also carried out a similar work for the VS patients and presented data on the size of tumor volume. The average tumor volume of the 43 VS patients included in our study is in very good agreement with the average tumor volume of Miller et al.

Datta et al.45 carried out work on post operative radiotherapy of brain tumors where they compared the GTV and clinical target volume (CTV) on CT and MRI image sets. The MRI volumes were significantly larger than CT estimated volumes in their study. MR is considered to be a superior imaging modality to CT as far as soft tissue contrast is concerned in brain imaging. However, our results indicate that the overlap between GTV-CT and GTV-MR is between 70% and 90% for the lesions with GTV larger than 5 cc and the overlap between GTV-CT and GTV-MR is between 60% and 70% for the lesions smaller than 5 cc. When the VS tumors are of larger dimensions, they try to compress the brain stem. Hence, it becomes more important to obtain both T1- and T2-weighted MR images along with CT images so that an optimum target volume can be estimated with the help of three image sets.

A number of reports are available which provide comparison between treatment modalities for VS including surgery versus radiation.46 The advantage of SRS and fractionated SRT is very low toxicity to the trigeminal nerve with hearing preservation. It is reported that five-year tumor local control is in the range of 94%–96%.7 The existing literature also provides information about the diagnosis of VS and tumor growth rate on yearly basis. There is an increase in the use of MRI for diagnostic purposes since no radiation is involved in detecting the VS tumor. Many tumors were detected accidentally with patients having no complaints. As MRI is costly, time-consuming and considered arduous for many patients but in some particular cases. like VS. there is very high specificity and sensitivity about 90%–95% associated with the MR imaging. It is therefore MRI that is considered to be the gold standard for brain lesions, especially in VS and hence it proves to be indispensible in SRS and fractionated SRT for VS. However, MRI imaging is not free from drawbacks. In our study, CT and MR images of the patients were taken using dedicated CT and MR scanners. There is always a chance of errors with the setting up of patients on two independent scanners. We accounted for and reported the data of the brainstem and right and left cochlea volume along with the GTV in Table 3. For brainstem, T1 estimated volume is higher than CT and T2 estimated volumes. In the case of right and left cochlea, T2 estimated volumes are higher than the CT and T1 estimated volumes.

6. Conclusions

We have presented a comprehensive comparison between the tumor volumes predicted by the CT image set and the MRI image sets. These results will be useful in estimating an accurate volume of VS for the pre- and post-treatment follow ups of the target volumes for the patients. The CT underestimates the tumor volume and T2-weighted MR overestimates the tumor volume in comparison to tumor volume estimated by T1-weighted MR. So it is recommended to use T1- and T2-weighted MR images along with CT images for the final estimation of tumor volume. To deliver precise and accurate dose to tumor tissue and to spare the normal tissue, it is essential to find a clear boundary between them. This is possible only when a flattering inter MRI modality like T1 and T2 is used in combination with the complementing imaging modality like computed tomography.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Contributor Information

Harjot Bajwa, Email: harjotbajwa1987@gmail.com.

Mukka Chandrashekhar, Email: dr.m.chandrashekar@gmail.com.

Sunil Dutt Sharma, Email: sdsharma@barc.gov.in.

Rohith Singareddy, Email: rohithsingareddy@gmail.com.

Dileep Gudipudi, Email: delgudi@yahoo.com.

Shabbir Ahmad, Email: shabbirdrp@gmail.com.

Alok Kumar, Email: dralokkumar20@gmail.com.

N.V.N. Madusudan Sresty, Email: drnvnm_sresty@induscancer.com.

Alluri Krishnam Raju, Email: allurivasu@rediff.com.

References

- 1.Norén G., Greitz D., Hirsch A. Gamma knife surgery in acoustic tumours. Acta Neurochir. 1993;58(Suppl.):104–107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9297-9_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito K., Kurita H., Sugasawa K. Analyses of neurootological complications after radiosurgery for acoustic neurinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39(5):983–988. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomassin J.M., Epron J.P., Regis J. Preservation of hearing in acoustic neuromas treated by gamma knife surgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1998;70(Suppl. 1):4–79. doi: 10.1159/000056409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flickinger J.C., Kondziolka D., Niranjan A. Results of acoustic neuroma radiosurgery: an analysis of 5 years’ experience using current methods. J Neurosurg. 2001;94(1):1–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews D.W., Suarez O., Goldman H.W. Stereotactic radiosurgery and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for the treatment of acoustic schwannomas: comparative observations of 125 patients treated at one institution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1265–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thust S.C., Yousry T. Imaging of skull base tumours. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21:304–318. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzoni A., Krengli M. Historical development of the treatment of skull base tumours. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fossatia P., Vavassori A., Deantonioc L. Review of photon and proton radiotherapy for skull base tumours. Rep Pract Oncol Rradiother. 2016;21:336–355. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmerman R.D. An overview of hypofractionation and introduction to this issue of seminars in radiation oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18(4):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijer O.W.M., Vandertop W.P., Baayen J.C. Single-fraction vs. fractionated linac-based stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: a single-institution study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(5):1390–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sailer S.L., Rosenman J.G., Soltys M., Soltys M., Cullip T.J., Chen J. Improving treatment planning accuracy through multimodality imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35(1):117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)85019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler M.L., Pitluck S., Petti P., Castro J.R. Integration of multimodality imaging data for radiotherapy treatment planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1653–1667. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyama H., Shirato H., Nishioka T. Magnetic resonance imaging system for three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy and its impact on gross tumor volume delineation of central nervous system tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(3):821–827. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoo V.S., Adams E.J., Saran F. A comparison of clinical target volumes determined by CT and MRI for the radiotherapy planning of base of skull meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46(5):1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishioka T., Shiga T., Shirato H. Image fusion between 18FDG-PET and MRI/CT for radiotherapy planning of oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(4):1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emami B., Sethi A., Petruzzelli G.J. Influence of MRI on target volume delineation and IMRT planning in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(2):481–488. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalwani A.K. Meningiomas, epidermoids, and other nonacoustic tumors of the cerebellopontine angle. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:707–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffat D.A., Saunders J.E., McElveen J.T., Jr. Unusual cerebello-pontine angle tumours. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1087–1098. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100125393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekkok I.H., Suzer T., Erbengi A. Non-acoustic tumors of the cerebellopontine angle. Neurosurg Rev. 1992;15:117–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00313506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brackmann D.E., Kwartler J.A. A review of acoustic tumors: 1983–8. Am J Otol. 1990;11:216–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Propp J.M., McCarthy B.J., Davis F.G., Preston-Martin S. Descriptive epidemiology of vestibular schwannomas. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:1–11. doi: 10.1215/S1522851704001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthies C., Samii M. Management of 1,000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): clinical presentation. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199701000-00001. discussion 9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogodzinski M.S., Harner S.G., Link M.J. Patient choice in treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arthurs B.J., Fairbanks R.K., Demakas J.J. A review of treatment modalities for vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2011;34:265–277. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallucci C.L., Victoria Ward A., Carney S., O’Donoghue G.M., Robertson I. Clinical features and outcomes in patients with non-acoustic cerebellopontine angle tumours. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:768–771. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.6.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali I., Tubbs J., Hibbitts K. Evaluation of the setup accuracy of a stereotactic radiotherapy head immobilization mask system using kV on-board imaging. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2010;11(3) doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v11i3.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.iPLAN® Automatic Image Fusion. Clinical White Paper.

- 28.ICRU-50 . ICRU; Bethesda: 1993. Prescribing, recording and reporting photon beam therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews D.W., Oscar Suarez H., Goldman W. Stereotactic radiosurgery and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for the treatment of acoustic schwannomas: comparative observations of 125 patients treated at one institution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(5):1265–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gino Fallone B., Ryan D., Rivest C., Riauka T.A., Murtha A.D. Assessment of a commercially available automatic deformable registration system. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2010;11(3) doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v11i3.3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crum W.R., Camara O., Hill D.L.G. Generalized overlap measures for evaluation and validation in medical image analysis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25(11):1451–1461. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.880587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulkarni B.S., Sharma S.D., Hansen V. A prospective study of OAR volume variations between two different treatment planning systems in radiotherapy. Int J Cancer Therapy Oncol. 2015;3(3) ISSN 23304049. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto M., Nagata Y., Okajima K. Differences in target outline delineation from CT scans of brain tumours using different methods and different observers. Radiother Oncol. 1999;50:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weltens C., Menten J., Feron M. Inter observer variations in gross tumor volume delineation of brain tumors on computed tomography and impact of magnetic resonance imaging. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60:49–59. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cattaneo G.M., Reni M., Rizzo G. Target delineation in post-operative radiotherapy of brain gliomas: inter observer variability and impact of image registration of MR (preoperative) images on treatment planning CT scans. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khoo V.S., Joon D.L. New developments in MRI for target volume delineation in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2006;79 Spec No. 1:S2-15. doi: 10.1259/bjr/41321492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhakar R., Haresh K.P., Ganesh T. Comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance based target volume in brain tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2007;3:121–123. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.34694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haque S., Hossain A., Quddus M.A., Jahan M.U. Role of MRI in the evaluation of acoustic schwannoma and its comparison to histo pathological findings. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2011;37:92–96. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v37i3.9120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozgen B., Oguz B., Dolgun A. Diagnostic accuracy of the constructive interference in steady state sequence alone for follow-up imaging of vestibular schwannomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(5):985–991. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X., Xu J., Xu M. Clinical features of intracranial vestibular schwannomas. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:57–62. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Langerberg R., Cdohmen A.J., de Bondt B.J. Linac radiotherapy in vestibular schwannomas: control rate and growth patterns. Adiol Neurotol. 2015;20:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rykaczewski B., Zabek M. A meta-analysis of treatment of vestibular schwannoma using Gamma Knife radiosurgery. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2014;18(1):60–66. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.39840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Apicella G., Paolini M., Deantonio L., Masini L., Krengli M. Radiotherapy for vestibular schwannoma: review of recent literature results. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller T., Lau T., Vasan R. Reporting success rates in the treatment of vestibular schwannomas: arewe accounting for the natural history? J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:914–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Datta N.R., David R., Gupta R.K., Lal P. Implications of contrast enhanced CT-based and MRI-based target volume delineations in radiotherapy treatment planning for brain tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2008;4:9–13. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.39598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zanoletti E., Faccioli C., Martini A. Surgical treatment of acoustic neuroma: outcomes and indications. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;2(1):395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]