Abstract

Background:

Various epidemiological studies have shown that exposure to environmental pollutants including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) might increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and their risk factors. This study aims to systematically review the association of PAH exposure with metabolic impairment.

Methods:

Data were collected by searching for relevant studies in international databases using the following keywords: “polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon” + “cardiovascular disease,” PAH + CVD, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and “air pollutant” + “CVD,” and the desired data were extracted and included in the study according to the systematic review process.

Results:

From the 14 articles included in the present systematic review, eight articles were conducted on the relationship between PAH and CVDs, four articles were conducted to examine the association of PAH exposure with blood pressure (BP), and two articles investigated the link between PAH and obesity.

Conclusions:

Most studies included in this systematic review reported a significant positive association of PAH exposure with increased risk of CVDs and its major risk factors including elevated BP and obesity. These findings should be confirmed by longitudinal studies with long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

Introduction

Nowadays, in spite of great advances in technology, as well as in the diagnosis and treatment modalities for various diseases, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are still the number one cause of death, accounting for a third of deaths worldwide.[1,2]

As shown in the literature, various factors such as malnutrition, stress, and exposure to environmental pollutants[3] could cause CVDs through atherosclerosis, angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction.[4] Epidemiological evidence indicates that exposure to certain substances in the air may cause increased risk of CVDs in human subjects.[5] Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are of a major constituent of air pollutants, which is positively associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and atherosclerosis.[6,7,8]

PAHs are strong atmospheric pollutants that are mainly produced by incomplete combustion of organic materials and fossil fuels emitted from exhausts of motor vehicles, cigarette smoke, coal burning, household cooking, and industrial products, which has caused a mounting concern among the public.[9,10] PAH exposure might increase the rate of CVDs.[11] PAH exposure occurs differently by inhalation, ingestion, and dermal exposure.[9] The absorbed PAH enters into the body's metabolic process and finally, it is excreted through the urine.[12] However, some believe that PAH accumulates in adipose tissues and liver.[13]

It is documented that PAH exposure is associated with decreased cardiac autonomic function.[9] In addition, PAH exposures in certain occupational circumstances and CVD-caused mortality have been reported to be positively correlated.[14,15] Moreover, PAH exposure is shown to worsen atherosclerosis through inflammation.[16] However, still these effects of PAHs remain controversial. This systematic review aims to assess the relationship of PAH exposure with CVDs and their risk factors.

Methods

In this systematic review, we searched the databases of PubMed, Medline, ProQuest, and Google Scholar from 2000 to 2017. A number of major, sensitive keywords including “polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon” AND “cardiovascular disease,” PAH AND CVD, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon AND “air pollutant” AND “CVD” were used to retrieve relevant papers.

Selection criteria and quality assessment of the articles

At first, we prepared a list of titles and abstracts of articles available in the above-mentioned databases; then the articles were studied independently for selecting relevant titles. Duplicates were omitted through examining the titles, name of the author(s), year of publication, journal name, and issue number. After a careful study of the texts of the articles, relevant articles were selected and the rest were not included in this review. Then, the quality of relevant articles was assessed using the standard checklist of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.[8] This checklist contains 43 diverse sections evaluating the various aspects of research methodology, including sampling methods, measurements, statistical analysis, and study objectives. In this checklist, by assigning one score to each section, papers could get a minimum score of 40 and a maximum score of 45. Finally, the articles that got scores higher than the minimum (40 points) were included in the review. The data of the selected articles were extracted in the form of name of the first author, study setting, year of publication, methodology, key findings, and outcomes.

Inclusion criteria

After achieving the required score during the quality assessment process, English-written articles examining the correlation between PAH and CVDs were included in this systematic review.

Exclusion criteria

Studies with scores lower than 40, based on the quality assessment checklist, as well as the studies that examined other pollutants were excluded from this review.

Results

At the first step of searching in the databases, 122 articles with relevant titles were obtained, from which 88 nonrelevant articles were then removed after careful examining of the titles. Further, twenty articles were also discarded due to being duplicated in the databases, leaving a total of 14 relevant articles for further review as they met the required inclusion criteria and obtained the necessary score based on the quality assessment checklist [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the database search, selection, and review process of articles

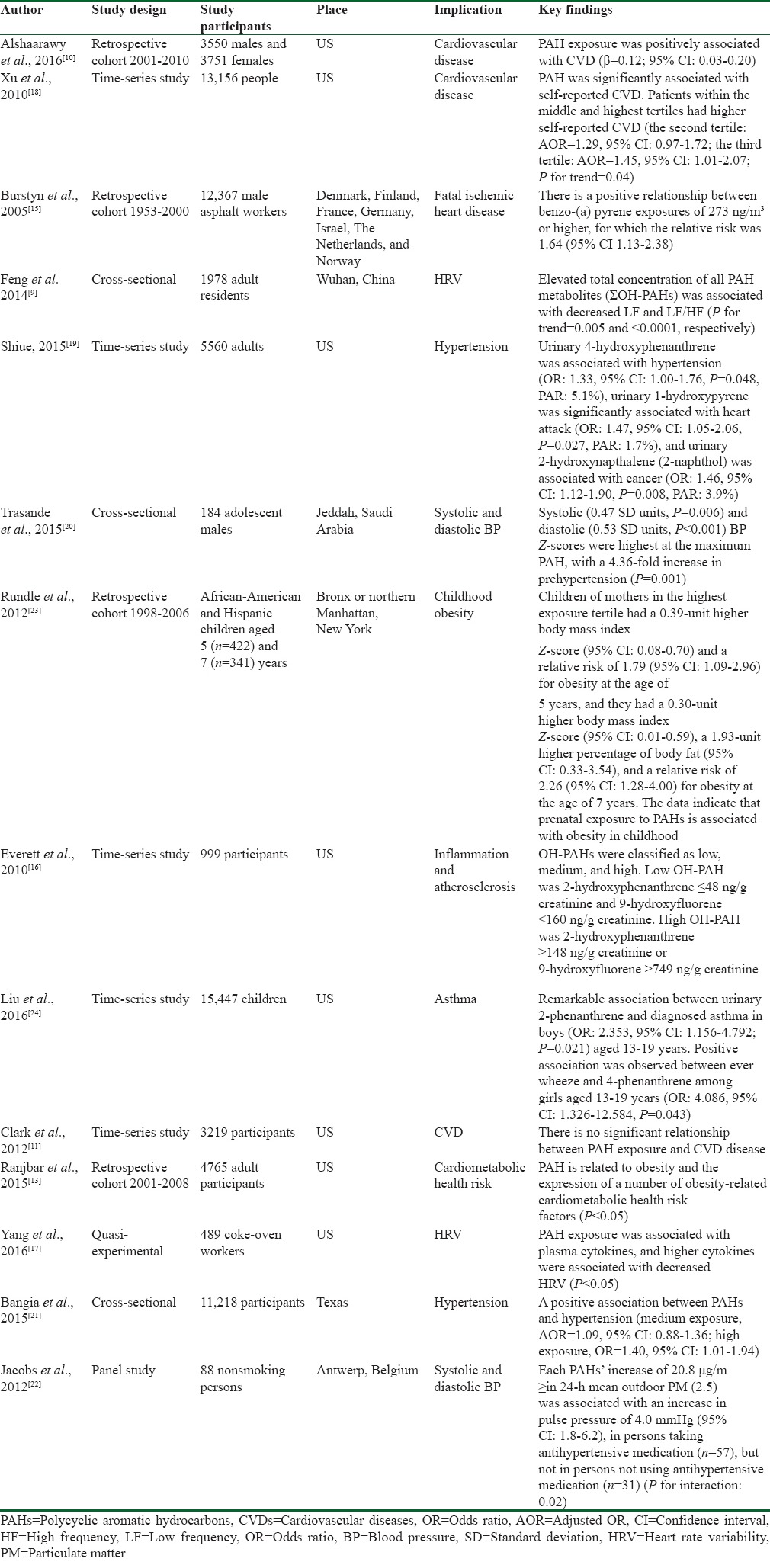

Of the 14 articles included in this review, eight articles assessed the relationship between PAH exposure and CVDs,[9,10,11,13,15,16,17,18] four examined this association with blood pressure (BP),[19,20,21,22] and two with obesity.[13,23] A summary of the main findings of these articles is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review

The information of the studies included in the review was as follows:

Methods: Time-series studies were the most frequent study type among the selected articles,[11,16,18,19,24] followed by retrospective cohort,[10,13,15,23] cross-sectional,[9,20,21] quasi experimental,[17] and panel[22] studies

Study population: The greatest number of participants was 15,447 individuals, as reported in one time-series study,[24] whereas the lowest number of participants was reported as 88 individuals in a panel study[22]

Setting: Most of the studies[10,11,12,13,16,17,18,19,21,23,24] were performed in the United States, while others were conducted in different geographical regions around the world including Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway,[15] China,[9] Saudi Arabia,[20] and Belgium[22]

Outcome: In most of the included studies, the outcome was reported as CVDs entitled, cardiovascular disease,[10,11,18] fatal ischemic heart disease,[15] heart rate variability,[9,17] inflammation, atherosclerosis,[16] and cardiometabolic heart rate.[13] However, the outcome was reported as BP with the titles of hypertension[19,21] and systolic and diastolic BP[20,22] in three of the studies, and as obesity[13,23] in one of them

Key findings: Majority of the studies revealed significant positive association between PAH exposure and risk of CVDs.[9,10,13,17,18] However, the results in the study by Clark et al.[11] showed the opposite, as they claimed that no significant relationship existed between PAH exposure and risk of CVDs. Moreover, a positive association was reported between PAH exposure and hypertension,[16,19,20,21,22] as well as between PAH exposure and obesity[13,23] in some of the studies.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we assessed the relationship of PAH exposure with cardiometabolic impairment. The findings showed that PAH exposure and risk of CVD were significantly positively correlated. PAH-rich sources such as cigarette smoke,[15] exhaust smokes, and cooking smoke[25,26,27] are known as risk factors influencing the human cardiovascular system. According to studies conducted in this area, people with cardiometabolic risk factors are more vulnerable in PAH-contaminated environments; here, the elderly[28] as well as people with diabetes,[29] overweight,[30] heart disease,[31] and high systemic inflammation[32] are under greater influence. A cross-sectional study[18] showed that PAH exposure is positively associated with the prevalence of self-reported CVDs. However, another study[11] demonstrated no significant connection between PAH exposure and CVDs through inflammation; however, this study did not discuss the possible underlying reasons to adequately support their findings.

Furthermore, the results showed that PAH exposure is significantly correlated with elevated BP. Accordingly, it was reported that systolic and diastolic BP is higher in students in schools close to oil refineries and those who are exposed to large amounts of this substance, as compared to those in schools outside this area.[20] Another study showed that the prevalence of hypertension increases with increasing age, living in high-traffic areas, and body mass index.[21] Likewise, studies conducted on people with elevated cholesterol, history of myocardial infarction, or diabetes, as well as those with physical disabilities, showed an increased prevalence of hypertension as a result of PAH exposure. A positive relationship is also documented between PAH exposure and BP level.[22] Experimental studies have indicated that exposure to PAH-containing organic compounds might lead to elevated arterial BP.[33]

It is also documented that a significant relationship exists between PAH exposure and obesity. In this regard, it is found that prenatal PAH exposure can demonstrate its effects as obesity at the age of 5, as well as higher BMI, obesity, and fat mass at the age of 7.[23] The effects observed on the body size of children prenatally exposed to PAH can be detected through accumulation of fat mass in their bodies, and not by their differences with fat-free mass. Women smoking cigarettes during pregnancy expose their fetuses to high concentrations of PAH, which is in turn correlated with weight gain in childhood, during adolescence and then, at young ages.[34,35]

Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review support a significant positive association of PAH exposure with increased risk of CVDs and their major risk factors, notably elevated BP and obesity. Longitudinal studies with long-term follow-up are necessary in this field.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was conducted as part of the project number 193042, funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. The current review was conducted without financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:143–52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318282ab8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;178:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabadán-Diehl C, Alam D, Baumgartner J. Household air pollution in the early origins of CVD in developing countries. Glob Heart. 2012;7:235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alshaarawy O, Zhu M, Ducatman A, Conway B, Andrew ME. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and serum markers of inflammation. A positive association that is more evident in men. Environ Res. 2013;126:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatnagar A. Environmental cardiology: Studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:692–705. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243586.99701.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeng HA, Pan CH, Diawara N, Chang-Chien GP, Lin WY, Huang CT, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-induced oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in relation to immunological alteration. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:653–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.055020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curfs DM, Knaapen AM, Pachen DM, Gijbels MJ, Lutgens E, Smook ML, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons induce an inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque phenotype irrespective of their DNA binding properties. FASEB J. 2005;19:1290–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2269fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Y, Sun H, Song Y, Bao J, Huang X, Ye J, et al. A community study of the effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites on heart rate variability based on the Framingham risk score. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:338–45. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alshaarawy O, Elbaz HA, Andrew ME. The association of urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Environ Int. 2016;89-90:174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark JD, 3rd, Serdar B, Lee DJ, Arheart K, Wilkinson JD, Fleming LE. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and serum inflammatory markers of cardiovascular disease. Environ Res. 2012;117:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Romanoff LC, Lewin MD, Porter EN, Trinidad DA, Needham LL, et al. Variability of urinary concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolite in general population and comparison of spot, first-morning, and 24-h void sampling. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20:526–35. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranjbar M, Rotondi MA, Ardern CI, Kuk JL. Urinary biomarkers of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are associated with cardiometabolic health risk. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brucker N, Charão MF, Moro AM, Ferrari P, Bubols G, Sauer E, et al. Atherosclerotic process in taxi drivers occupationally exposed to air pollution and co-morbidities. Environ Res. 2014;131:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstyn I, Kromhout H, Partanen T, Svane O, Langård S, Ahrens W, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fatal ischemic heart disease. Epidemiology. 2005;16:744–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181310.65043.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett CJ, King DE, Player MS, Matheson EM, Post RE, Mainous AG., 3rd Association of urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and serum C-reactive protein. Environ Res. 2010;110:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang B, Deng Q, Zhang W, Feng Y, Dai X, Feng W, et al. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, plasma cytokines, and heart rate variability. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19272. doi: 10.1038/srep19272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X, Cook RL, Ilacqua VA, Kan H, Talbott EO, Kearney G. Studying associations between urinary metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and cardiovascular diseases in the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:4943–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiue I. Are urinary polyaromatic hydrocarbons associated with adult hypertension, heart attack, and cancer? USA NHANES, 2011-2012. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22:16962–8. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trasande L, Urbina EM, Khoder M, Alghamdi M, Shabaj I, Alam MS, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, brachial artery distensibility and blood pressure among children residing near an oil refinery. Environ Res. 2015;136:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bangia KS, Symanski E, Strom SS, Bondy M. A cross-sectional analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and diesel particulate matter exposures and hypertension among individuals of Mexican origin. Environ Health. 2015;14:51. doi: 10.1186/s12940-015-0039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs L, Buczynska A, Walgraeve C, Delcloo A, Potgieter-Vermaak S, Van Grieken R, et al. Acute changes in pulse pressure in relation to constituents of particulate air pollution in elderly persons. Environ Res. 2012;117:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rundle A, Hoepner L, Hassoun A, Oberfield S, Freyer G, Holmes D, et al. Association of childhood obesity with maternal exposure to ambient air polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1163–72. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Xu C, Jiang ZY, Gu A. Association of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and asthma among children 6-19 years: NHANES 2001-2008 and NHANES 2011-2012. Respir Med. 2016;110:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Niu Z, Van Niekerk D, Xue J, Zheng L. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from coal combustion: Emissions, analysis, and toxicology. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2008;192:1–28. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71724-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramesh A, Walker SA, Hood DB, Guillén MD, Schneider K, Weyand EH. Bioavailability and risk assessment of orally ingested polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int J Toxicol. 2004;23:301–33. doi: 10.1080/10915810490517063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simko P. Factors affecting elimination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from smoked meat foods and liquid smoke flavorings. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:637–47. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia X, Song X, Shima M, Tamura K, Deng F, Guo X. Effects of fine particulate on heart rate variability in Beijing: A panel study of healthy elderly subjects. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitsel EA, Quibrera PM, Christ SL, Liao D, Prineas RJ, Anderson GL, et al. Heart rate variability, ambient particulate matter air pollution, and glucose homeostasis: The environmental epidemiology of arrhythmogenesis in the women's health initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:693–703. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JC, Cavallari JM, Stone PH, Christiani DC. Obesity is a modifier of autonomic cardiac responses to fine metal particulates. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1002–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheeler A, Zanobetti A, Gold DR, Schwartz J, Stone P, Suh HH. The relationship between ambient air pollution and heart rate variability differs for individuals with heart and pulmonary disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:560–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luttmann-Gibson H, Suh HH, Coull BA, Dockery DW, Sarnat SE, Schwartz J, et al. Systemic inflammation, heart rate variability and air pollution in a cohort of senior adults. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:625–30. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasser LB, Lundstrom DL, Zangar RC, Springer DL, Mahlum DD. Elevated blood pressure and heart rate in rats exposed to a coal-derived complex organic mixture. J Appl Toxicol. 1989;9:47–52. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550090109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oken E, Levitan EB, Gillman MW. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:201–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power C, Jefferis BJ. Fetal environment and subsequent obesity: A study of maternal smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:413–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]