Abstract

In this issue of Molecular Cell, Nuñez et al. (2016) report that site-specific integration of foreign DNA into CRISPR loci by the Cas1-Cas2 integrase complex is promoted by a host factor, IHF (integration host factor), that binds and bends CRISPR leader DNA.

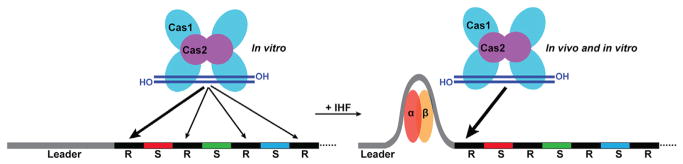

CRISPR-Cas systems are diverse, RNA-guided adaptive immune systems that defend a broad range of prokaryotes against invasions by viruses and plasmids (Makarova et al., 2015). A crucial initial step for CRISPR-Cas-mediated defense is the incorporation of DNA fragments (spacers) from invaders into host CRISPR loci (CRISPRs are host genomic arrays comprised of alternating direct repeat and spacer sequences and adjacent leader region; see Figure 1). This so-called “adaptation” or “spacer acquisition” step provides the affected organisms with heritable immunity against future encounters with specific invaders (Sternberg et al., 2016). Interestingly, new spacers are integrated specifically at the leader end of the CRISPR array. However, mechanisms specifying the polarized addition of spacers at the leader-proximal (i.e., “first”) repeat have remained a mystery. Mutational analyses in diverse CRISPR-Cas systems have revealed a role for repeat-proximal leader DNA elements in CRISPR spacer acquisition (Wei et al., 2015; Yosef et al., 2012). It has been presumed that these important leader DNA elements act as specific binding sites to recruit the Cas1-Cas2 integrase complex (Nuñez et al., 2014), thereby restricting spacer integration to the leader-proximal repeat rather than at other repeats distributed throughout a CRISPR array. However, recent in vitro studies have revealed that the E. coli Cas1-Cas2 complex alone integrates spacers at all CRISPR repeat sequences and also at sites outside of the CRISPR array (Nuñez et al., 2015 and Figure 1). These results contrast with the in vivo behavior (selective spacer integration into the leader-proximal repeat) and suggest that proteins other than Cas1 and Cas2 might be responsible for leader recognition and directing spacer integration to the leader-repeat border. In this issue, Nuñez et al. identify a non-Cas protein in E. coli, integration host factor (IHF), that is essential for spacer acquisition in vivo and functions through binding and bending the CRISPR leader to promote Cas1-Cas2-mediated spacer integration at the leader-proximal repeat of the CRISPR array (Figure 1).

Figure 1. IHF Promotes Spacer Integration at the Leader End of the E. coli CRISPR Locus.

Left: provided with double-stranded DNA (blue) as protospacer substrates, E. coli Cas1-Cas2 (cyan and purple) complex integrates spacers into the CRISPR locus at all repeats (R, black bars) in vitro, with a small preference (~30%–40% of total) for the leader (gray bar)-proximal repeat. Right: the IHF heterodimer (orange and yellow) binds and bends leader DNA, promoting spacer integration at the leader-proximal end (80% of total) of the repeats in vitro. IHF and the IHF binding site in the leader are required for new spacer acquisition in vivo, which occurs exclusively at the leader end.

The initial clue that IHF might serve as a trans-acting factor specifying CRISPR leader-proximal spacer integration came from the astute observation that a consensus IHF binding site overlaps with a repeat-adjacent leader element that was previously determined to be critical for spacer acquisition (Yosef et al., 2012). It is a pleasing coincidence that the name of the identified factor (integration host factor) matches the sought after activity (factor for integration at host CRISPR). Indeed, E. coli IHF originally attained its name to signify its role in directing site-specific lambda phage integration. IHF belongs to a broader family of nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) that play key roles in controlling prokaryotic chromosome organization, replication, segregation, and gene expression (Dillon and Dorman, 2010). IHF functions as a heterodimer (made up of α and β subunits) and exhibits DNA binding at defined consensus sites. Sequence-specific DNA binding by IHF induces dramatic bending of the DNA such that it adopts a “U-turn” conformation (Rice et al., 1996).

The Nuñez et al. study provides several compelling lines of evidence that leader DNA binding and bending by the IHF heterodimer channels the Cas1-Cas2 integrase complex to incorporate spacers at the repeat adjacent to the site of IHF-DNA interaction. The authors verify binding of IHF at the predicted binding site in the CRISPR leader DNA in vitro and demonstrate that spacer integration in vivo is abolished when the IHF binding site within the leader DNA is disrupted or when the gene encoding either IHF subunit is deleted. In vitro integration assays performed in the absence or presence of recombinant IHF reveal that IHF promotes integration at the leader-repeat junction: addition of purified IHF shifts the majority (80%) of spacer integration to the leader-proximal repeat, compared to 30%–40% in the absence of IHF. The observation that CRISPR repeats and especially the leader-proximal repeat remain preferred sites of integration even in the absence of IHF suggests an intrinsic ability of the Cas1-Cas2 complex to recognize the sequences and/or structures of CRISPR repeat and seemingly also leader elements (this observation deserves further exploration). Finally, generating an IHF binding site within the leader of an E. coli CRISPR locus (CRISPR-II) that is naturally defective for integration and also lacks a predicted IHF binding site results in integration activity, at least in vitro.

Another significant contribution of the study is that it reveals an unanticipated role of leader DNA topology in the spacer acquisition step of the CRISPR-Cas pathway. In the absence of IHF, DNA supercoiling is needed for efficient spacer integration in vitro (current study plus Nuñez et al., 2015). In contrast, addition of IHF stimulates linear DNA substrates to undergo spacer acquisition. These results indicate that the failure of linear DNA to act as a target for spacer integration in the absence of IHF is due to a DNA topology constraint. Taken together with the known properties of IHF to bend specific sites into “U-turn” DNA structures, the results suggest that IHF-induced DNA restructuring is a key signal for favorable site-specific integration at a CRISPR repeat. A key unresolved question is precisely how IHF specifically exerts its effect in stimulating the site of spacer integration by the Cas1-Cas2 complex.

The discovery of the involvement of a non-Cas host factor in leader recognition is a substantial step forward in understanding the adaptive immunity of CRISPR-Cas systems. CRISPR-Cas systems are prevalent in diverse species of prokaryotes (Makarova et al., 2015). The fact that IHF is absent in numerous pro-karyotes that contain active CRISPR-Cas systems (including Gram-positive bacteria and archaea) indicates that host factors other than IHF are likely involved in directing adaptation at the leader end in these organisms. Natural candidates for these host factors are other NAPs that bind and restructure DNA and are ubiquitous components of prokaryotic cells (Dillon and Dorman, 2010). Alternatively, the degree to which host factor-induced leader DNA restructuring is important for integration site specificity could be highly variable among CRISPR-Cas systems. For example, in other systems, Cas1-Cas2 might intrinsically recognize leader-repeat junction information to guide leader-proximal spacer integration (Rollie et al., 2015). Moreover, many CRISPR-Cas systems have auxiliary Cas proteins (Cas4, Csn2, Cas9) that are involved in spacer acquisition (Sternberg et al., 2016). These auxiliary Cas proteins could assist Cas1-Cas2 in targeting the leader proximal repeat, either directly (through physical association with Cas1-Cas2 to alter properties of the complex) or indirectly (by binding and altering DNA topology at the integration site).

Finally, the finding that IHF is essential for E. coli spacer integration provides yet another example highlighting an emerging principle that CRISPR-Cas systems do not act autonomously, but instead require non-Cas host factors to regulate and orchestrate their actions. Other examples include: (1) transcriptional repression of E. coli CRISPR-Cas expression by the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein, H-NS, (2) requirement for RNase III for crRNA processing by type II CRISPR-Cas systems, and (3) role of DNA repair and replication proteins in spacer acquisition (Levy et al., 2015 ; Makarova et al., 2015). It can be anticipated that the discovery of key roles for additional non-Cas proteins in CRISPR-Cas function will be a recurrent theme into the future, given both the functional diversity of different CRISPR-Cas systems and the breadth of possible prokaryotic hosts. CRISPR-Cas systems themselves appear to be acquired by host microbes through horizontal gene transfer (HGT). The implication is that CRISPR-Cas systems newly acquired by HGT might function in certain hosts but not others, depending on whether requisite host factors are present.

References

- Dillon SC, Dorman CJ. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:185–195. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Goren MG, Yosef I, Auster O, Manor M, Amitai G, Edgar R, Qimron U, Sorek R. Nature. 2015;520:505–510. doi: 10.1038/nature14302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:722–736. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez JK, Kranzusch PJ, Noeske J, Wright AV, Davies CW, Doudna JA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:528–534. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez JK, Lee AS, Engelman A, Doudna JA. Nature. 2015;519:193–198. doi: 10.1038/nature14237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez JK, Bai L, Harrington LB, Hinder TL, Doudna JA. Mol Cell. 2016;62:824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.027. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice PA, Yang S, Mizuuchi K, Nash HA. Cell. 1996;87:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollie C, Schneider S, Brinkmann AS, Bolt EL, White MF. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08716. http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.08716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg SH, Richter H, Charpentier E, Qimron U. Mol Cell. 2016;61:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Chesne MT, Terns RM, Terns MP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1749–1758. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef I, Goren MG, Qimron U. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5569–5576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]