ABSTRACT

The SmeDEF pump of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is negatively regulated by SmeT. In this study, strains KJΔT (smeT deletion mutant) and KJT-Dm (mutant with a defective SmeT-binding site) showed increased resistance to chloramphenicol/nalidixic acid/macrolides and susceptibility to aminoglycoside. Overexpression of the SmeDEF pump, in either KJΔT or KJT-Dm, downregulated smeYZ expression, which is responsible for the reduced aminoglycoside resistance. Furthermore, the SmeRySy two-component regulatory system was downregulated in response to SmeDEF overexpression, which supports its involvement in the regulatory circuit.

KEYWORDS: antibiotic resistance, bacteria, efflux pump, two-component regulatory system

TEXT

Among the mechanisms known to be involved in multidrug resistance (MDR), the efflux pump is a major determinant, conferring resistance to various antibiotics simultaneously (1). Given the extrusion ability of efflux systems, it is generally accepted that the overexpression of efflux pumps is responsible for antimicrobial resistance. However, it has also been reported that overexpression of efflux pumps increases resistance to some antibiotics and reduces resistance to other antibiotics (2, 3). Accordingly, the overall expression of MDR pumps has been closely monitored.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, an opportunistic human pathogen, shows a significant degree of intrinsic resistance to a variety of antibiotics (4). Sequencing of the S. maltophilia genome revealed the presence of eight resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) efflux systems, namely, SmeABC, SmeDEF, SmeGH, SmeIJK, SmeMN, SmeOP, SmeVWX, and SmeYZ (5). smeDEF expression is negatively regulated by smeT, which is located upstream and divergently transcribed from the smeDEF operon (6). The known substrates of the SmeDEF pump include chloramphenicol, quinolone, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and macrolides (7). The SmeYZ efflux system contributes mainly to resistance against aminoglycosides (AGs) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8), and its expression is positively regulated by the SmeRySy two-component regulatory system (TCS), which is located upstream of the smeYZ operon (9). The expression of SmeDEF or SmeYZ has been reported to be linked to the MDR phenotype of clinical isolates (7, 8). The expression of the individual RND efflux pump has been extensively studied (6, 9, 10, 11); however, coordinated expression among these RND efflux systems in S. maltophilia has not been reported so far. In this study, we demonstrated that the expression of the SmeYZ pump is attenuated in response to SmeDEF overexpression in S. maltophilia.

Inactivation of smeT increased susceptibility to AG.

A smeT in-frame deletion mutant of S. maltophilia strain KJ, KJΔT, was prepared for our study (9). The susceptibility of KJΔT to antibiotics was assessed by the agar dilution method and interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (12). The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that inhibited visible growth.

SmeT plays a negative regulatory role in the expression of the smeDEF operon (6). As expected, the MICs of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin increased for KJΔT (Table 1), which is consistent with the reported substrate profile of the SmeDEF pump (7). However, an interesting observation attracted our attention; the susceptibility of KJΔT to AGs increased compared to that in the wild-type KJ strain (Table 1). This phenomenon was not expected, since overexpression of the efflux pump is generally related to a decrease in susceptibility.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of S. maltophilia strain KJ and its derived mutants

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) fora: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SmeDEF pump substrates |

SmeYZ pump substrates |

|||||

| CHL | CIP | ERY | AMI | KAN | GEN | |

| KJ | 8 | 1 | 64 | 1,024 | 256 | 1,024 |

| KJΔDEF | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 1,024 | 256 | 1,024 |

| KJΔYZ | 8 | 1 | 128 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| KJΔYZΔT | 32 | 8 | 512 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| KJΔT | 32 | 8 | 512 | 128 | 64 | 128 |

| KJΔTΔDEF | 4 | 1 | 32 | 1,024 | 256 | 512 |

| KJT-Dm | 32 | 8 | 128 | 256 | 64 | 256 |

| KJT-DmΔDEF | 4 | 0.5 | 16 | 1,024 | 256 | 1,024 |

CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; AMI, amikacin; KAN, kanamycin; GEN, gentamicin.

Inactivation of smeT attenuated the expression of smeYZ.

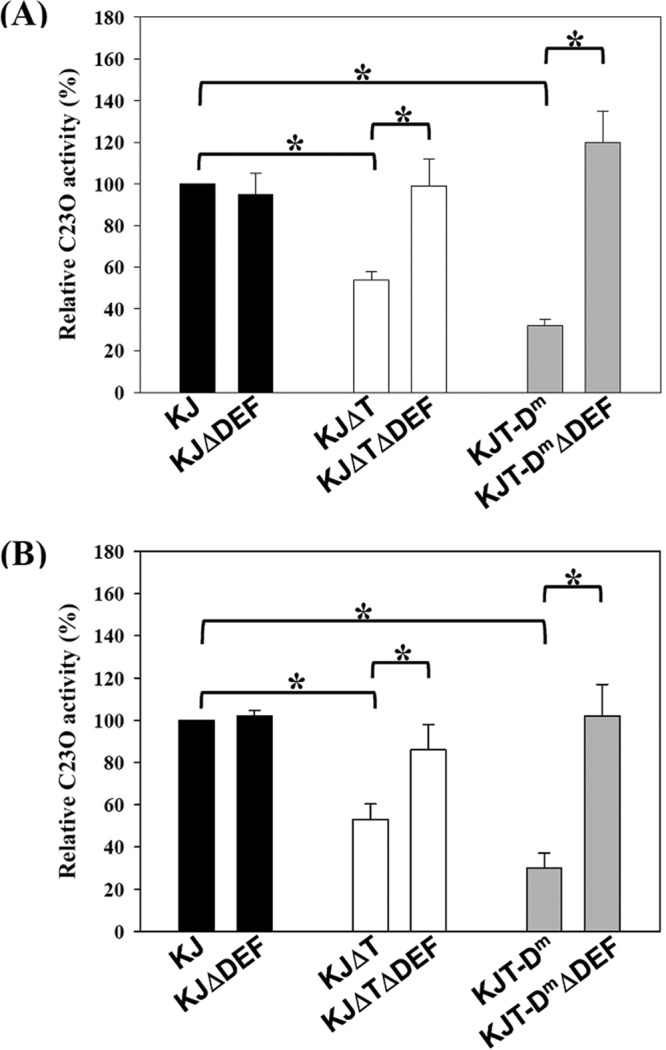

The resistance to AGs reported in S. maltophilia is attributable to aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs), RND-type efflux pumps, and outer membrane permeability (8, 13, 14–16). Given that SmeT acts as a transcriptional repressor, we wondered whether SmeT also regulates the expression of AMEs, RND-type efflux pumps, and lytic transglycosidase genes, in addition to the smeDEF operon. To address this question, the transcripts of five annotated AME genes (aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene [Smlt0191], aac(2′)-Ic [Smlt1669], aph(3′)-IIc [Smlt2120], streptomycin 3′-phosphotransferase gene [Smlt2336], and aac(6′)-Iz [Smlt3615]), eight RND-type transporter genes (smeB, smeE, smeH, smeJ, smeN, smeP, smeW, and smeZ), and six lytic transglycosylase genes (mltA, mltB1, mltB2, mltD1, mltD2, and slt) (5) in wild-type KJ and KJΔT strains were comparatively assessed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) as described previously (3). The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The 16S rRNA gene was chosen as the normalizing gene. All transcripts tested, except for smeE and smeZ, exhibited no significant difference between the KJ and KJΔT strains (Fig. 1). SmeE transcripts were indeed increased in KJΔT, which supports the theory that SmeT plays a role in repressing smeDEF expression. However, smeZ transcript levels were lower in the KJΔT strain compared to those in the wild-type KJ strain (Fig. 1). The plasmid pSmeYxylE, which carries the promoterless xylE gene downstream of the smeY promoter, was constructed in our previous study (9). The plasmid pSmeYxylE showed lower C23O activity in KJΔT than in the wild-type KJ strain (Fig. 2A), which further confirms that inactivation of smeT attenuates the expression of smeYZ.

FIG 1.

The amounts of smeT, smeE, and smeZ transcripts of wild-type KJ and its derived SmeDEF overexpression mutants, KJΔT and KJT-Dm. The mRNA expression levels of the indicated genes were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). Error bars indicate the standard deviations of data from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05 (significance calculated by Student's t test).

FIG 2.

The impact of SmeDEF overexpression on the activity of promoters PsmeY and PsmeRy. The smeY and smeRy transcriptional fusion constructs, pSmeYxylE and pSmeRyxylE, were transported into the assayed S. maltophilia strains by conjugation. The overnight-cultured plasmid-harboring strains were inoculated into fresh Luria broth with an initial optical density at 450 nm (OD450 nm) of 0.15 and cultured for 5 h, and the C23O activities were determined. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of data from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05 (significance calculated by Student's t test). (A) C23O activities expressed by pSmeYxylE. (B) C23O activities expressed by pSmeRyxylE.

Considering that the major substrates of the SmeYZ pump are AGs (8), we wondered whether the decrease in ΔsmeT-mediated AG resistance results from the downregulated expression of smeYZ. We assumed that knocking out smeYZ in a ΔsmeT background would then bring the level of AG susceptibility to that found in smeYZ knockout mutants, if the decrease in ΔsmeT-mediated AG resistance resulted from smeYZ downregulated expression. A smeYZ and smeT double mutant, KJΔYZΔT, was constructed, and KJΔYZΔT had AG susceptibility comparable to that of KJΔYZ (Table 1), which suggests that the ΔsmeT-mediated decrease in AG resistance involves SmeYZ.

Considering that the major substrates of the SmeYZ pump are AGs (8), we wondered whether the ΔsmeT-mediated AG resistance compromise results from the downregulated expression of smeYZ. We assumed that the simultaneous inactivation of smeT and smeYZ would exacerbate the observed reduction in AG resistance if the decrease in ΔsmeT-mediated AG resistance is independent of SmeYZ function. A smeYZ and smeT double mutant, KJΔYZΔT, was constructed; however, no further compromise in AG resistance was observed in KJΔYZΔT (Table 1), suggesting that the ΔsmeT-mediated compromise in AG resistance involves SmeYZ.

SmeDEF overexpression downregulates smeYZ.

It has been demonstrated that altering the expression of a single RND pump may have a downstream effect on any number of other RND efflux systems. Therefore, we further considered the possibility that smeDEF overexpression, rather than smeT inactivation, is the major cause for ΔsmeT-mediated smeYZ downregulated expression. To test this, a smeT and smeDEF double mutant, KJΔTΔDEF, was constructed. The effect of SmeDEF overexpression on smeYZ expression in KJΔT was assessed by evaluating PsmeY activity in KJΔT and KJΔTΔDEF. As shown in Fig. 2A, the decrease in PsmeY activity in KJΔT reverted to the level of that in the wild-type strain once ΔsmeDEF was introduced into the chromosome of KJΔT. However, inactivation of smeDEF in the wild-type KJ strain did not significantly affect the promoter activity of PsmeY (Fig. 2A). In addition, introduction of the ΔsmeDEF allele into the chromosome of KJΔT reverted the level of AG susceptibility to that of wild-type KJ (Table 1), emphasizing the linkage between SmeDEF overexpression and a ΔsmeT-mediated decrease in AG resistance.

Next, we sought to construct a smeDEF overexpression strain using an alternative mechanism in which the strain still harbored an intact SmeT protein. The intergenic (IG) region of smeT-smeD has been well characterized, and the inverted-repeat sequence (5′-ACAAACAAGCATGTATGT-3′) for SmeT binding was identified (6) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The double-crossover homologous recombination strategy was used to replace the SmeT-binding sequence (ACAAACAAGCATGTATGT) in the chromosomes of KJ cells with ACAAACAAGCATCTAGAT. An 863-bp DNA fragment containing a 349-bp smeT N terminus, complete smeT-smeD intergenic region, and 288-bp smeD N terminus was obtained by PCR using the primers TD-F and TD-R (see Table S1) and then cloned into pEX18Tc, which resulted in the plasmid pTD. The introduction of the three mutated nucleotides (Fig. S1) into the SmeT-binding sequence within plasmid pTD was carried out by site-directed mutagenesis PCR. The chromosomal SmeT-binding sequence of wild-type KJ was replaced with the mutated SmeT-binding sequence by the double-crossover homologous recombination strategy (8), yielding mutant KJT-Dm. Mutant KJT-Dm should have a defect in the interaction between SmeT and the operator region despite the presence of a wild-type SmeT, which, in turn, should derepress smeDEF expression. The smeT and smeE transcript levels and antibiotic susceptibility of strain KJT-Dm were determined by qRT-PCR and susceptibility testing, respectively. Compared to that in wild-type KJ, the level of smeE transcripts was higher in KJT-Dm (Fig. 1); the MICs of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin were also elevated in KJT-Dm compared to those in the wild-type KJ strain (Table 1). This signifies the success of the KJT-Dm construct, which exhibits a phenotype of smeDEF overexpression and normal smeT expression. In addition, we noticed that the level of smeZ transcripts and the MICs of AGs were decreased in KJT-Dm compared to those in the control (Fig. 1 and Table 1), consistent with observations in strain KJΔT. Next, the ΔsmeDEF allele was introduced into strain KJT-Dm, yielding KJT-DmΔDEF. The promoter activity of smeY in KJT-Dm was lower than that in wild-type KJ but reverted to a wild-type level when the ΔsmeDEF allele was introduced into the chromosome of KJT-Dm (Fig. 2A). A consistent conclusion was also obtained from the antibiotic susceptibilities of KJ, KJT-Dm, and KJT-DmΔDEF (Table 1). Altogether, our results provide strong evidence that the decreased MICs of AG in KJΔT and KJT-Dm result from the overexpression of SmeDEF, independent of smeT deletion.

SmeDEF overexpression downregulates the SmeRySy TCS.

Since the expression of the smeYZ operon is under the positive control of the SmeRySy TCS (9), which is divergently transcribed from the smeYZ operon, we examined whether SmeDEF overexpression-mediated smeYZ downregulated expression relies on the transcriptional activity of the smeRySy operon. To test this, the plasmid pSmeRyxylE was constructed for promoter transcriptional assays. A 574-bp DNA fragment upstream of the smeRy gene was amplified by PCR from the chromosome of S. maltophilia KJ using the primer sets SmeY5-F and SmeY5-R and cloned upstream of the promoterless xylE gene in plasmid pRKXylE, yielding plasmid pSmeRyxylE. The promoter activity of the smeRySy operon in KJΔT was lower than that in wild-type KJ and reverted to a wild-type level when the ΔsmeDEF allele was introduced into the chromosome of KJΔT (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed in the strains KJ(pSmeRyxylE), KJT-Dm(pSmeRyxylE), and KJT-DmΔDEF(pSmeRyxylE) (Fig. 2B). This was not due to a deletion of SmeDEF, since the promoter activities of the smeRySy operon were comparable in strains KJ and KJΔDEF (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that SmeDEF overexpression leads to a downregulation of the SmeRySy TCS, which ultimately results in decreased expression of the SmeYZ pump.

Concluding remarks.

The phenomenon that overexpression of an RND-type efflux pump increases resistance to antimicrobials known to be substrates for the overexpressed pump, concomitant with a higher susceptibility to other antimicrobials, has been reported in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. maltophilia. MexCD-OprJ-overexpressing P. aeruginosa displays an increased resistance to fluoroquinolones, the fourth-generation cephalosporin cefepime, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol but shows reduced resistance to most other β-lactams (2). Although MexAB-OprM downregulated expression has been considered a critical determinant for the increase in β-lactam susceptibility (2), the exact link between MexCD-OprJ overexpression and MexAB-OprM downregulated expression remains unclear. In addition, the SmeVWX-overproducing S. maltophilia exhibits a phenotype characterized by elevated resistance to chloramphenicol, quinolone, and tetracycline and susceptibility to AG. The SmeVWX-overexpression-mediated increase in AG susceptibility results from SmeX overexpression rather than from inverse changes in the expression levels of the other efflux pump (3). In this article, we have described another example, where overexpression of the SmeDEF pump of S. maltophilia resulted in increased resistance to substrates of the SmeDEF pump and susceptibility to AG. We have further elucidated that SmeYZ downregulated expression is the key determinant for the SmeDEF overexpression-mediated increase in AG susceptibility and proposed the possibility of the involvement of the SmeRySy TCS in this regulatory circuit.

SmeSy and SmeRy of S. maltophilia exhibit protein identities of 30% and 38% with CpxA and CpxR of Escherichia coli, respectively. The CpxAR system of E. coli can sense and respond to envelope alterations, either the overexpression of the outer membrane protein NlpE or the disruption of phosphatidylglycerol homeostasis (17). Compared to the cytoplasmic environment, the bacterial envelope is a relatively crowded space, since about one-fourth to one-third of all bacterial genes encode membrane proteins (18). Therefore, overexpression of the SmeDEF pump may augment this challenging situation and stress the envelope environment. SmeSy may sense this stress and trigger a negative autoregulation, thereby attenuating the expression of the SmeYZ pump to alleviate the envelope stress. Another possibility is that overexpression of SmeDEF effluxes an inducing agent, which is normally sensed by the SmeRySy TCS, and decreases the expression of smeRySy and smeYZ. In addition, we also observed that SmeDEF was expressed at an appreciable basal level in wild-type KJ. Deletion of smeDEF from the chromosome of wild-type KJ caused a 2-fold decrease in MICs of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin (Table 1) but did not affect smeYZ expression (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the basal expression level of smeDEF makes a mild contribution to antibiotic resistance without causing an envelope stress response.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant MOST 104-2320-B-010-023-MY3 from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02685-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li XZ, Nikaido H. 2009. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria: an update. Drugs 69:1555–1623. doi: 10.2165/11317030-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Tsuda M, Okamoto K, Nomura A, Wada T, Nakahashi M, Nishino T. 1998. Characterization of the MexC-MexD-OprJ multidrug efflux system in ΔmexA-mexB-oprM mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:1938–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CH, Huang CC, Chung TC, Hu RM, Huang YW, Yang TC. 2011. Contribution of resistance-nodulation-division efflux pump operon smeU1-V-W-U2-X to multidrug resistance of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5826–5833. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00317-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooke JS. 2012. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:2–41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crossman LC, Gould VC, Dow JM, Vernikos GS, Okazaki A, Sebaihia M, Saunders D, Arrowsmith C, Carver T, Peters N, Adlem E, Kerhornou A, Lord A, Murphy L, Seeger K, Squares R, Rutter S, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Harris D, Churcher C, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Thomson NR, Avison MB. 2008. The complete genome, comparative and functional analysis of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia reveals an organism heavily shielded by drug resistance determinants. Gen Biol 9:R74. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-r74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez P, Alonso A, Martinez JL. 2002. Cloning and characterization of SmeT, a regulator of the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3386–3393. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3386-3393.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso A, Martinez JL. 2000. Cloning and characterization of SmeDEF, a novel multidrug efflux pump from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:3079–3086. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.11.3079-3086.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin YT, Huang YW, Chen SJ, Chang CW, Yang TC. 2015. The SmeYZ efflux pump of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia contributes to drug resistance, virulence-related characteristics, and virulence in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4067–4073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00372-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu CJ, Huang YW, Lin YT, Ning HC, Yang TC. 2016. Inactivation of SmeSyRy two-component regulatory system inversely regulates the expression of SmeYZ and SmeDEF efflux pumps in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. PLoS One 11:e0160943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li XZ, Li Z, Poole K. 2002. SmeC, an outer membrane multidrug efflux protein of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:333–343. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.333-343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin CW, Huang YW, Hu RM, Yang TC. 2014. SmeOP-TolCsm efflux pump contributes to multidrug resistance of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2405–2408. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01974-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 25th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S25. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang YW, Liou RS, Lin YT, Huang HH, Yang TC. 2014. A linkage between SmeIJK efflux pump, cell envelope integrity, and sigma E-mediated envelope stress response in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. PLoS One 9:e111784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambert T, Ploy MC, Denis F, Courvalin P. 1999. Characterization of the chromosomal aac(6′)-Iz gene of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:2366–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okazaki A, Avison MB. 2007. Aph(3′)-IIc, an aminoglycoside resistance determinant from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:359–360. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00795-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu CJ, Huang YW, Lin YT, Yang TC. 2016. Inactivation of lytic transglycosylase increases susceptibility to aminoglycosides and macrolides by altering the outer membrane permeability of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3236–3239. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03026-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delhaye A, Collet J-F, Laloux G. 2016. Fine-tuning of the Cpx envelope stress response is required for cell wall homeostasis in Escherichia coli. mBio 7:e00047–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elofsson A, von Heijne G. 2007. Membrane protein structure: prediction versus reality. Annu Rev Biochem 76:125–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.163539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.