ABSTRACT

Co-trimoxazole, a fixed-dose combination of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and trimethoprim (TMP), has been used for the treatment of bacterial infections since the 1960s. Since it has long been assumed that the synergistic effects between SMX and TMP are the consequence of targeting 2 different enzymes of bacterial folate biosynthesis, 2 genes (pabB and nudB) involved in the folate biosynthesis of Escherichia coli were deleted, and their effects on the susceptibility to antifolates were tested. The results showed that the deletion of nudB resulted in a lag of growth in minimal medium and increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP. Moreover, deletion of nudB also greatly enhanced the bactericidal effect of TMP. To elucidate the mechanism of how the deletion of nudB affects the bacterial growth and susceptibility to antifolates, 7,8-dihydroneopterin and 7,8-dihydropteroate were supplemented into the growth medium. Although those metabolites could restore bacterial growth, they had no effect on susceptibilities to the antifolates. Reverse mutants of the nudB deletion strain were isolated to further study the mechanism of how the deletion of nudB affects susceptibility to antifolates. Targeted sequencing and subsequent genetic studies revealed that the disruption of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway could reverse the phenotype caused by the nudB deletion. Meanwhile, overexpression of folM could also lead to increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP. These data suggested that the deletion of nudB resulted in the excess production of tetrahydromonapterin, which then caused the increased susceptibility to antifolates. In addition, we found that the deletion of nudB also resulted in increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP in Salmonella enterica. Since dihydroneopterin triphosphate hydrolase is an important component of bacterial folate biosynthesis and the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway also exists in a variety of bacteria, it will be interesting to design new compounds targeting dihydroneopterin triphosphate hydrolase, which may inhibit bacterial growth and simultaneously potentiate the antimicrobial activities of antifolates targeting other components of folate biosynthesis.

KEYWORDS: nudB, sulfamethoxazole, susceptibility, tetrahydromonapterin, trimethoprim

INTRODUCTION

Co-trimoxazole, a fixed-dose combination of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and trimethoprim (TMP), has been used as a broad-spectrum antibacterial drug since the 1960s. Initially, co-trimoxazole was used to treat urinary tract infections and lower respiratory tract infections (1, 2), but later on, it was found to have good prophylactic activity against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (3). The use of co-trimoxazole greatly increased with the emergence of the HIV epidemic in the 1980s, since it provided good protection against various opportunistic infections during the pre-antiretroviral therapy (ART) era (4–9). In recent years, researchers have found that co-trimoxazole is able to prevent the development of tuberculosis in HIV-positive patients, especially in those who have not received prior ART (10). At present, co-trimoxazole is still one of the first-line drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, and community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections (11); however, the widespread use of co-trimoxazole has resulted in increasing resistance, just like with many other antimicrobial agents (12). Thus, it has become a challenge to improve the antibacterial activity of co-trimoxazole and reduce the emergence of co-trimoxazole-resistant bacteria at the same time.

Both SMX and TMP are antifolates, which inhibit the growth of bacterial cells by blocking bacterial folate biosynthesis. SMX and TMP target 2 different enzymes involved in bacterial folate biosynthesis: SMX targets dihydropteroate synthetase, while TMP targets dihydrofolate reductase (13, 14). This is the long-assumed reason why these 2 compounds have synergistic effects (15). If this assumption is true, it may be possible to design new compounds that target other critical enzymes involved in bacterial folate biosynthesis, which could potentiate the antibacterial effect of either SMX or TMP. To test this hypothesis, we deleted the nudB gene (which is involved in the de novo biosynthesis of folate) in both Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica and then tested its impact on the susceptibilities to SMX and TMP. The results are reported herein.

RESULTS

Effects of nudB and pabB deletion on bacterial susceptibility to SMX and TMP in E. coli.

It has long been assumed that the reason why SMX and TMP have a good synergistic effect is because these 2 drugs target 2 different enzymes in the bacterial folate biosynthesis pathway. If this is the case, the knockout of other genes involved in folate biosynthesis could potentiate the antibacterial effect of either SMX or TMP, or both. The pabB and nudB genes were knocked out in E. coli, and we tested the susceptibilities of these 2 mutants to SMX, TMP, rifampin (RIF), and ampicillin. The results showed that the deletion of pabB did not affect the susceptibility of E. coli to any of the drugs tested; however, the deletion of nudB made E. coli hypersensitive to both SMX and TMP, as determined by the MIC tests (Table 1). In addition, the MICs of SMX and TMP for the nudB deletion mutant were determined in the presence of exogenous dihydropteroate and 7,8-dihydroneopterin, and the results showed that these additions had no effect on SMX and TMP susceptibilities of the mutant (Table 2). The susceptibility of the nudB deletion mutant to other antibacterial drugs (rifampin and ampicillin) was also tested, and the results show that the deletion of nudB does not affect the susceptibilities to these 2 drugs (MIC for rifampin, 8 μg/ml; MIC for ampicillin, 4 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of different strains to TMP and SMX

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) for: |

|

|---|---|---|

| TMP | SMX | |

| E. coli W3110 | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110/pCA24N | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110/pCA24N-nudB | 0.64 | 256 |

| E. coli W3110/pCA24N-folX | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110/pUC19 | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110/pUC19-folM | 0.16 | 64 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB | 0.02 | 4 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB/pCA24N | 0.02 | 4 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB/pCA24N-nudB | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB/pUC19 | 0.02 | 4 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB/pUC19-folM | 0.01 | 1 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolX | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolX/pCA24N | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolX/pCA24N-folX | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolM | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolM/pCA24N | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔfolM/pCA24N-folM | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX/pCA24N | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX/pCA24N-folX | 0.02 | 8 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM/pUC19 | 0.32 | 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM/pUC19-folM | 0.02 | 8 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | 0.32 | 1,024 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2/pUC19 | 0.32 | 1,024 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2/pUC19-folM | 0.16 | 512 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 ΔnudB | 0.08 | 256 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 ΔnudB/pUC19 | 0.08 | 256 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 ΔnudB/pUC19-folM | 0.04 | 128 |

TABLE 2.

Effects of 7,8-dihydropteroate (DHP) and 7,8-dihydroneopterin (DHNP) on susceptibility of E. coli W3110 and E. coli W3110 ΔnudB to TMP

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TMP, SMX in absence of DHP and DHNP | TMP, SMX in presence of 20 μg/ml DHP | TMP, SMX in presence of 20 μg/ml DHNP | |

| E. coli W3110 | 0.32, 128 | 0.32, 128 | 0.32, 128 |

| E. coli W3110 ΔnudB | 0.02, 4 | 0.02, 4 | 0.02, 4 |

Effect of the nudB deletion on the growth of E. coli.

The nudB gene encodes dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase, which is also an important enzyme involved in bacterial folate biosynthesis. Previously, Gabelli et al. found that even though the deletion of nudB resulted in a remarkable decrease in folate concentration, the nudB knockout mutant did not have any growth defects in E. coli (16).

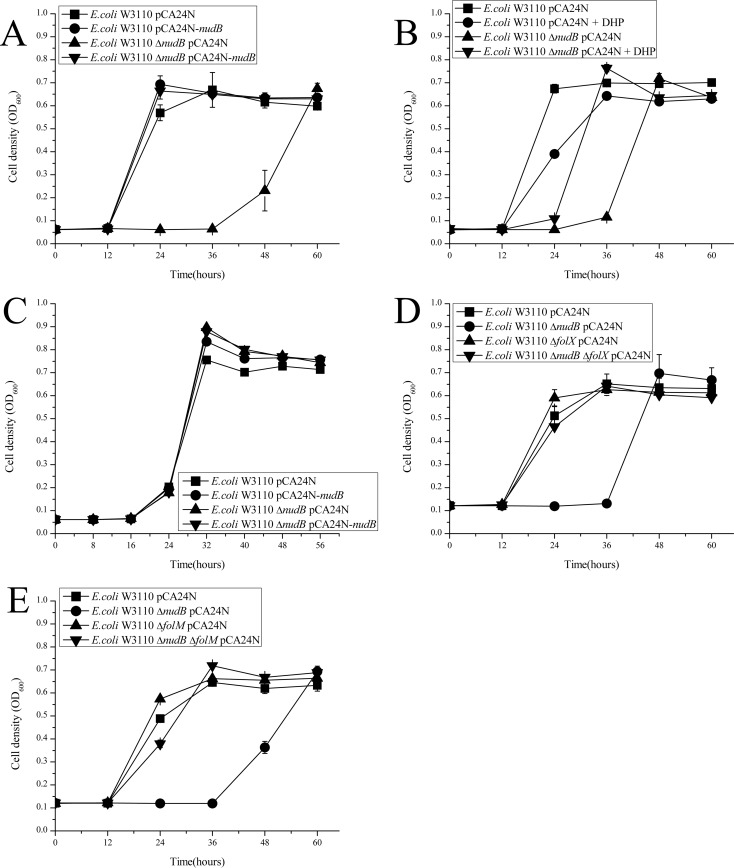

Growth curves of the wild-type and the nudB deletion strains were compared using E minimal medium with or without exogenous folate intermediate metabolites (dihydropteroate and dihydroneopterin) to determine the effect of nudB deletion on bacterial growth. As shown in Fig. 1A, when W3110 ΔnudB was grown in E minimal medium, it showed a prolonged lag phase of growth, which could be completely reversed by adding exogenous dihydroneopterin (Fig. 1C) and partially reversed by dihydropteroate (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Growth curves of different E. coli strains on E minimal medium: in the absence of 7,8-dihydropteroate and 7,8-dihydroneopterin (A), in the presence of 20 μg/ml DHP (B), and in the presence of 20 μg/ml DHNP (C). (D and E) Growth curves of W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX strain (D) and W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM strain (E). Growth of the bacteria at 37°C was measured by taking OD600 every 8 or 12 h using the Syergy H1 Hybrid reader (BioTek, USA). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

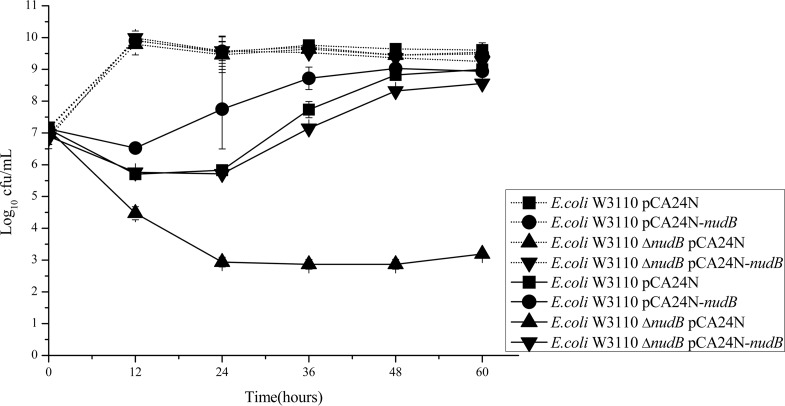

Effect of the nudB deletion on the bactericidal effect of TMP against E. coli.

TMP exposure experiments were performed to further test the effect of the nudB deletion on the bactericidal effect of TMP against E. coli. The results show that the cell numbers of the wild-type strain decreased from 7 log10 CFU/ml to a little bit less than 6 log10 CFU/ml after 12 h of TMP treatment; however, cell numbers of the nudB deletion strain decreased from 7 log10 CFU/ml to less than 4.5 log10 CFU/ml (Fig. 2). After 24 h of treatment, there was no further decrease in cell numbers for the wild-type strain, but for the nudB deletion strain, the cell numbers kept decreasing to less than 3 log10 CFU/ml. From 24 h on, the cell numbers of the wild-type strain started to increase gradually, but the cell numbers of the nudB deletion strain remained static until 60 h of treatment. During the course of the TMP treatment, the complemented strain behaved just like the wild-type strain, while the nudB overexpression strain was slightly more resistant to the TMP treatment.

FIG 2.

Time-kill curves of different E. coli strains after exposure to 2 μg/ml TMP. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the results from 3 independent experiments. The dashed lines represent the strains treated without drugs, while the solid lines represent strains treated with 2 μg/ml TMP.

Identification of reverse mutations in the nudB deletion mutant.

Thirty reverse mutants were isolated to further understand the reason why the deletion of the nudB gene led to the increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP. Target sequencing was performed for 2 genes involved in tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis (folX and folM). From Table 3, it can be seen that the sequence variations were identified in 18 of these reverse mutants: 7 of the reverse mutants have insertions in either of the 2 genes, 5 of the strains have substitutions, and 6 of them have deletions. Eleven of the 30 mutants have no mutations in the 2 genes. For those reverse mutants that have mutations in either folX or folM, their MICs for TMP were determined to be identical to that of E. coli W3110. In addition, six of the reverse mutants without any mutation in folX and folM were randomly selected, and their MICs for TMP were all determined to be around 0.32 μg/ml (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). For the 8 reverse mutants that have insertions in either folX or folM, DNA sequencing data showed that all of those insertion sequences are from a transposase: GTAATGACTCCAACTTATTGATAGTGTTTTATGTTCAGATAATGCCCGATGACTTTGTCATGCAGCTCCACCGATTTTGAGAACGACAGCGACTTCCGTCCCAGCCGTGCCAGGTGCTGCCTCAGATTCAGGTTATGCCGCTCAATTCGCTGCGTATATCGCTTGCTGATTACGTGCAGCTTTCCCTTCAGGCGGGATTCATACAGCGGCCAGCCATCCGTCATCCATATCACCACGTCAAAGGGTGACAGCAGGCTCATAAGACGCCCCAGCGTCGCCATAGTGCGTTCACCGAATACGTGCGCAACAACCGTCTTCCGGAGACTGTCATACGCGTAAAACAGCCAGCGCTGGCGCGATTTAGCCCCGACATAGCCCCACTGTTCGTCCATTTCCGCGCAGACGATGACGTCACTGCCCGGCTGTATGCGCGAGGTTACCGACTGCGGCCTGAGTTTTTTAAGTGACGTAAAATCGTGTTGAGGCCAACGCCCATAATGCGGGCTGTTGCCCGGCATCCAACGCCATTCATGGCCATATCAATGATTTTCTGGTGCGTACCGGGTTGAGAAGCGGTGTAAGTGAACTGCAGTTGCCATGTTTTACGGCAGTGAGAGCAGAGATAGCGCTGATGTCCGGCGGTGCTTTTGCCGTTACGCACCACCCCGTCAGTAGCTGAACAGGAGGGACAGCTGATAGAAACAGAAGCCACTGGAGCACCTCAAAAACACCATCATACACTAAATCAGTAAGTTGGCAGCATCACCAGAACCTTCG.

TABLE 3.

Mutations identified in reverse mutants of E. coli ΔnudB

| Strain | folX (nt)a | folM (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| KL-1 | WT | WT |

| KL-2 | Insertion at 333b | WT |

| KL-3 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-4 | Substitution 59G→A | WT |

| KL-5 | WT | WT |

| KL-6 | WT | WT |

| KL-7 | WT | WT |

| KL-8 | WT | WT |

| KL-9 | WT | WT |

| KL-10 | WT | WT |

| KL-11 | WT | WT |

| KL-12 | Insertion at 207b | WT |

| KL-13 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-14 | WT | Substitution 557T→G |

| KL-15 | Insertion at 143b | WT |

| KL-16 | WT | WT |

| KL-17 | Insertion at 140b | WT |

| KL-18 | Insertion at 160b | WT |

| KL-19 | Insertion at 90b | WT |

| KL-20 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-21 | Substitutions 2T→G, 5C→T | WT |

| Insertion at 4 (GGCCAGTC) | ||

| KL-22 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-23 | WT | WT |

| KL-24 | WT | WT |

| KL-25 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-26 | WT | Substitution 92A→C |

| KL-27 | Insertion at 111b | WT |

| KL-28 | WT | 4-base deletion at 654 (TACT) |

| KL-29 | Substitutions 2T→G, 5C→T | WT |

| Insertion at 4 (GGCCAGTC) | ||

| KL-30 | WT | WT |

nt, nucleotides; WT, wild type.

Insertion of large fragment.

Effect of the disruption of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway on SMX and TMP susceptibility.

Two double-knockout mutants (E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX and E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM) were constructed to confirm that the disruption of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway could reverse the phenotype caused by the nudB deletion. From Table 1, it can be seen that the susceptibilities to SMX and TMP of both of the double mutants are the same as the wild-type strain, and when the intact folX or folM gene was transformed into the corresponding double mutant, it became hypersensitive to both SMX and TMP again. Meanwhile, 2 more single-knockout mutants (E. coli W3110 ΔfolX and E. coli W3110 ΔfolM) were constructed, and the susceptibilities of these 2 mutants to both SMX and TMP were also determined. The results showed that the knockout of either folX or folM had no effect on the susceptibilities to SMX and TMP. The growth curves of the above-mentioned 4 strains were also determined parallel to the wild-type strain and the nudB deletion strain. As shown in Fig. 1D and E, E. coli W3110 ΔfolX, E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX, E. coli W3110 ΔfolM, and E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM grew as normally as the wild-type strain in the E minimal medium.

Effect of folM overexpression on bacterial susceptibility to TMP and SMX.

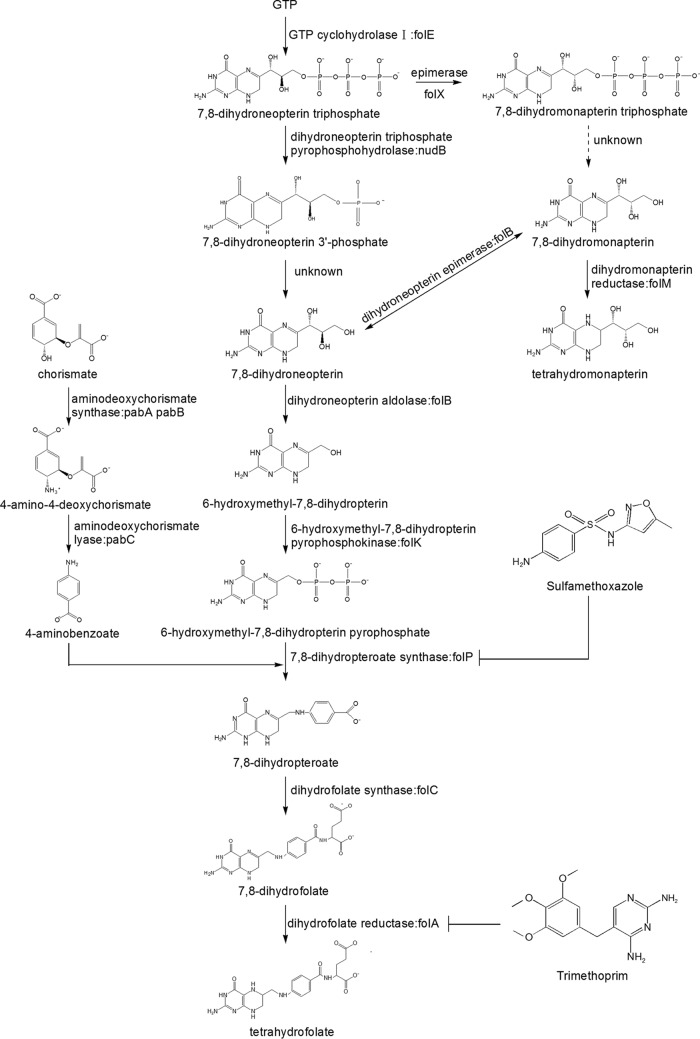

FolM catalyzes the formation of tetrahydromonapterin, which is the end product of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 3). To explore the impact of the excess production of tetrahydromonapterin on the susceptibility to TMP and SMX, the folM gene from E. coli was overexpressed in E. coli W3110, E. coli W3110 ΔnudB, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 ΔnudB, respectively. The results showed that the overexpression of folM caused increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP in all of the strains tested (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Schematic diagram of folate metabolic pathway.

Effect of the nudB deletion on bacterial susceptibility to SMX and TMP in S. enterica.

The nudB gene was deleted in S. enterica, and susceptibility of the nudB deletion mutant to SMX and TMP was determined. As shown in Table 1, the deletion of nudB also caused increased susceptibility to both of the drugs; however, the nudB deletion mutant grew as normally as its parental strain in the E minimal medium (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the deletion of nudB, which encodes an important component of the folate de novo biosynthesis pathway in bacteria, led to increased susceptibility to 2 widely used antifolate drugs (SMX and TMP) in both E. coli and S. Typhimurium. Thus, it is possible to design a new antimicrobial recipe consisting of compounds targeting different components of the bacterial folate biosynthesis pathway.

The idea that the deletion of other important components of folate biosynthesis might potentiate the antibacterial activity of preexisting antifolates comes from the old story between SMX and TMP, i.e., their synergistic effect. We tried to delete several genes (pabB, pabC, nudB, folB, folK, folP, and folC) involved in the de novo biosynthesis of folate in E. coli, but only 2 mutants were obtained (E. coli W3110 ΔnudB and E. coli W3110 ΔpabB). The remaining 5 mutants were still in the process of construction. The effects of the deletion of those 2 genes on bacterial growth were analyzed, and the data showed that the deletion of pabB did not affect bacterial growth; however, the deletion of nudB led to an obvious lag of growth in the E minimal medium. From the beginning, NudB was biochemically characterized to be a nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase, likely a member of the MutT family of proteins. However, the nudB gene did not complement the MutT− mutator phenotype; on the contrary, the deletion of nudB resulted in decreased frequency of spontaneous nalidixic acid-resistant mutants (17). Later on, NudB was found to be a dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatase, a Nudix enzyme involved in folate biosynthesis, and the deletion of nudB led to a marked reduction in folate synthesis, although no growth defects were observed (16). The difference between our study and the previous report may result from different strain backgrounds. Our results, in combination with the previous report, confirmed that although NudB plays an important role in de novo folate biosynthesis, it is not the only copy of dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatase in E. coli.

The effects of the deletion of those 2 genes on the bacterial susceptibility to antifolates were also tested, and the results showed that the deletion of nudB led to increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP, but the deletion of pabB did not have any effect. PabB is responsible for the synthesis of para-aminobenzoic acid, one of the precursors of folate de novo biosynthesis. These data suggest that the synergistic effect between SMX and TMP may not result simply from targeting 2 different key enzymes of the same pathway. Thus, it was not surprising to find out that the reason why the deletion of nudB led to increased sensitivity to antifolates is unrelated to folate biosynthesis. Although exogenous intermediate folate metabolites could complement the growth lag caused by nudB deletion, they had no effect on the susceptibilities to SMX and TMP.

If we go deeper into the bacterial pterin biosynthesis, we can see that after the hydrolysis of GTP, dihydroneopterin triphosphate can be utilized by at least 2 proteins: one of those is NudB, and the other is FolX (dihydroneopterin triphosphate epimerase) (18), a key component of tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis (19). Thus, we wondered if the deletion of nudB would make dihydroneopterin triphosphate flux more into the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway and then lead to the increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP. If this was the case, reverse mutations could be identified in folX. To test this hypothesis, reverse mutants of the nudB deletion mutant were isolated, and targeted sequencing was performed for folX and folM, with folM encoding dihydrobiopterin reductase in E. coli (19). As expected, of the reverse mutants isolated, more than half of them had mutations (or insertions or deletions) in either the folX or folM gene. To further verify that the mutation of folX or folM could reverse the phenotype caused by the nudB deletion, 2 double-knockout mutants (E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolX and E. coli W3110 ΔnudB ΔfolM) were constructed, and the results showed that the susceptibilities of these 2 mutants to SMX and TMP were the same as the wild-type strain. Meanwhile, further deletion of folX and folM could also complement the lag of growth caused by the nudB deletion. In addition, we found that the overexpression of FolM, which was thought to be an alternative to FolA, led to increased susceptibility to both TMP and SMX. These data suggest that in E. coli, although other dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatases may exist, FolX is definitely the predominant consumer of dihydroneopterin triphosphate in the absence of NudB, which is consistent with the previous observation that tetrahydromonapterin production far exceeds folate production (19). As a result, the deletion of nudB leads to the excess production of tetrahydromonapterin, which causes increased susceptibility to SMX and TMP. Since intermediate metabolites of tetrahydromonapterin are very unstable, it is very difficult to measure the fluctuation of those metabolites in vivo. Although we now know that the deletion of nudB can make dihydroneopterin triphosphate flux more into the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway, it is still unclear why this makes E. coli hypersensitive to antifolates. Through protein BLAST, we found that a variety of bacteria (including E. coli) contain components of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway (Table S2), but the biological functions of tetrahydromonapterin still remain unknown. The only clue we could find is that in Pseudomonas aeruginosa tetrahydromonapterin is the cofactor for phenylalanine hydroxylase (PhhA), which is involved in tyrosine biosynthesis (19). So far, however, no homologue of PhhA has been identified in E. coli. We also tried to add exogenous tyrosine (50 μg/ml) to the growth medium to see if it would affect the susceptibility to SMX and TMP, and the results showed that the addition made E. coli slightly more resistant to TMP (2 times the increase of the MIC). Further studies are required to reveal how the deletion of nudB results in hypersensitivity to both SMX and TMP.

The effect of the nudB deletion on the bactericidal activity of TMP was also investigated, and the results showed that the deletion of nudB greatly enhanced the bactericidal activity of TMP. Since a previous study showed that the deletion of nudB resulted in the decreased frequency of spontaneous nalidixic acid-resistant mutants (17), we wondered whether the deletion of nudB also led to the decreased rate of spontaneous resistance to TMP. A mutagenesis assay was performed (see the supplemental material). From the data we obtained, we could see that for the nudB deletion strain, no spontaneous resistant mutant could be obtained in the presence of 1 μg/ml TMP (Table S4). To better understand why no TMP spontaneous resistant mutant could be obtained for the nudB deletion strain in the presence of a 1-μg/ml concentration of the drug, 40 colonies of TMP spontaneous mutants derived from the wild-type strain and the complemented strain (20 colonies each) were selected, and their MICs for TMP were determined subsequently. The results showed that the MICs for those TMP spontaneous mutants were all determined to be 4 μg/ml, about 15 times those of their parental strain (E. coli W3110). Since 1 μg/ml TMP (50 times the MIC for TMP of E. coli W3110 ΔnudB) was used for the mutagenesis assay and 2 μg/ml TMP (100 times the MIC for TMP of E. coli W3110 ΔnudB) was used for the killing curve assay, such high concentrations of the drug might prevent the growth of spontaneous resistant mutants of E. coli W3110 ΔnudB. Taken together, all of the above-mentioned data suggest that the enhanced bactericidal effect of TMP caused by the nudB deletion is related to the increased susceptibility to TMP.

Except for E. coli, components of the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway also exist in a variety of other bacteria, including many pathogenic bacteria, such as S. enterica and Yersinia pestis. This indicates that the deletion of nudB may cause similar phenotypes in other bacteria, such as S. enterica. Therefore, the nudB gene was also deleted in S. enterica. Unlike E. coli, the deletion of nudB did not affect the growth of S. enterica, which also proved that NudB is not the only copy of dihydroneopterin triphosphate hydrolase in S. enterica. As expected, the deletion of nudB also led to increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP in S. enterica, although to a lesser extent than that of E. coli. This difference may be explained by the following: in E. coli, NudB is the major producer of dihydroneopterin monophosphate since the deletion of nudB causes an obvious lag of bacterial growth, but it is not the same in S. enterica. In addition, with the overexpression of E. coli, FolM also resulted in increased susceptibility to both SMX and TMP, suggesting that the excess production of tetrahydromonapterin may also be the cause of the phenotype.

Taken together, we found that the deletion of nudB led to a lag in bacterial growth and increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP in E. coli. In addition, the deletion of nudB also led to increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP in S. enterica. Further genetic studies showed that the deletion of nudB could make dihydroneopterin triphosphate flux more into the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway, yielding an excess production of tetrahydromonapterin, which causes increased sensitivity to both SMX and TMP. Although NudB is not essential for bacterial growth, dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphate hydrolase is required for bacterial growth, since dihydroneopterin monophosphate is required for bacterial de novo folate biosynthesis, which needs to be catalyzed by dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphate hydrolase. On the other hand, from the data of protein BLAST and previous reports, the tetrahydromonapterin biosynthesis pathway also exists in a variety of bacteria. Thus, it is possible to design new compounds targeting dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphate hydrolase, which may inhibit the growth of bacteria and simultaneously potentiate the antimicrobial activities of other antifolates (such as SMX and TMP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

E. coli K-12 W3110 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 were obtained from laboratory stock. They were both grown in LB liquid medium or E minimal medium (we dissolved 0.2 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 2 g of citric H2O, 13.09 g of K2HPO4·3H2O, and 3.5 g of NaNH4HPO4·4H2O in 1 liter of deionized water) supplemented with 0.5% d-(+)-glucose on LB agar plates (1.5% agar). The gene knockout mutants were constructed with the λ Red recombination system, as previously described (20). The mutants were verified by junction PCR and subsequent sequencing using primers that anneal to the genomic region outside the recombination locus. The double-knockout mutants were generated using the same procedures, except that the kanamycin resistance gene of the single-gene knockout mutant was first eliminated using the helper plasmid pCP20. Complemented strains of all of the mutants were constructed as follows: the nudB gene was amplified using the primers nudB-F and nudB-R, the folX gene was amplified using the primers folX-F and folX-R, and the folM gene was amplified using the primers folM-F and folM-R. Each of the intact wild-type genes was digested with endonuclease BglII and XbaI, cloned into pCA24N or pUC19, and then transformed into the corresponding mutant. All plasmids, primers, and strains that we used are listed in Table S1.

Drug and reagent preparation.

The following antibiotics were used: sulfamethoxazole (SMX), rifampin, trimethoprim (TMP), and ampicillin. All of the antibiotics were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Drugs were solubilized according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and stock solutions were filter sterilized and stored in aliquots at −20°C. 7,8-Dihydropteroate powder was purchased from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland), dissolved in 0.01 M NaOH, filter sterilized, and stored at −80°C.

Drug susceptibility tests.

Bacterial cells were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5 to 1.0) and diluted to 105 CFU/ml in fresh LB. Then, 10-fold serial dilutions were plated onto the LB agar solid plates containing various concentrations of SMX, TMP, rifampin, and ampicillin: 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1,024 μg/ml SMX; 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, 0.32, 0.64, 1.28, and 2.56 μg/ml TMP; 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 μg/ml RIF; and 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 μg/ml ampicillin. Cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the compound required to inhibit 99% of the bacterial CFU.

Drug exposure experiments.

Bacterial cells were grown to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5 to 1.0) and diluted to an OD600 of ∼0.1 in fresh LB medium. For TMP treatment, 2 μg/ml TMP was used. Cultures were incubated at 37°C without shaking, aliquots of the samples were taken at regular intervals, and serial dilutions were performed before plating.

Identification of reverse mutations in E. coli W3110 ΔnudB.

E. coli W3110 ΔnudB was grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.8, collected by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 15 min, at room temperature), and resuspended in fresh medium at a concentration of 108 CFU/ml. Subsequently, 100 μl of the cells was spread onto LB agar plates containing 0.1 μg/ml TMP and incubated at 37°C overnight to select the reverse mutants. Single colonies were purified, and then liquid cultures were grown to determine the susceptibilities to both SMX and TMP. Subsequently, genomic DNA was extracted from all of the reverse mutants, and targeted sequencing of PCR amplicons of 2 genes (folX and folM) was performed. The primers folXd and folMd used in the targeted sequencing are described in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the State Key Development Program for Basic Research of China (grants 2012CB518802 and 2009CB522605) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31300050).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02378-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reeves D, Faiers M, Pursell R, Brumfitt W. 1969. Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole: comparative study in urinary infection in hospital. Br Med J 1:541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5643.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes DTD. 1969. Single-blind comparative trial of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole and ampicillin in the treatment of exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Br Med J 4:470–473. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5681.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes WT, McNabb PC, Makres TD, Feldman S. 1974. Efficacy of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole in the prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 5:289–293. doi: 10.1128/AAC.5.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider MM, Hoepelman AI, Eeftinck Schattenkerk JK, Nielsen TL, van der Graaf Y, Frissen JP, van der Ende IM, Kolsters AF, Borleffs JC. 1992. A controlled trial of aerosolized pentamidine or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as primary prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 327:1836–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212243272603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canessa A, Del Bono V, De Leo P, Piersantelli N, Terragna A. 1992. Cotrimoxazole therapy of Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis in AIDS patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 11:125–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01967063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plourde PJ, D'Costa LJ, Agoki E, Ombette J, Ndinya-Achola JO, Slaney LA, Ronald AR, Plummer FA. 1992. A randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of fleroxacin versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in men with culture-proven chancroid. J Infect Dis 165:949–952. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr A, Tindall B, Brew BJ, Marriott DJ, Harkness JL, Penny R, Cooper DA. 1992. Low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis for toxoplasmic encephalitis in patients with AIDS. Ann Intern Med 117:106–111. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-2-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeHovitz JA, Pape JW, Boncy M, Johnson WD Jr. 1986. Clinical manifestations and therapy of Isospora belli infection in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 315:87–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607103150203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youle M, Chanas A, Gazzard B. 1990. Treatment of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related pneumonitis with foscarnet: a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Infect 20:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(90)92302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasse B, Walker AS, Fehr J, Furrer H, Hoffmann M, Battegay M, Calmy A, Fellay J, Di Benedetto C, Weber R, Ledergerber B, Swiss HIV Cohort Study. 2014. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis is associated with reduced risk of incident tuberculosis in participants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2363–2368. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01868-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, Moran GJ, Nicolle LE, Raz R, Schaeffer AJ, Soper DE. 2011. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 52:e103–e120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huovinen P, Sundström L, Swedberg G, Sköld O. 1995. Trimethoprim and sulfonamide resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:279. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCullough JL, Maren TH. 1973. Inhibition of dihydropteroate synthetase from Escherichia coli by sulfones and sulfonamides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 3:665–669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.3.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker B, Meyer RB Jr. 1967. Irreversible enzyme inhibitors. LXXXIV. Candidate active-site-directed irreversible inhibitors of dihydrofolic reductase. IX. Derivatives of 2, 4-diaminopyrimidine. 3. J Pharm Sci 56:570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darrell JH, Garrod LP, Waterworth PM. 1968. Trimethoprim: laboratory and clinical studies. J Clin Pathol 21:202. doi: 10.1136/jcp.21.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabelli SB, Bianchet MA, Xu W, Dunn CA, Niu ZD, Amzel LM, Bessman MJ. 2007. Structure and function of the E. coli dihydroneopterin triphosphate pyrophosphatase: a Nudix enzyme involved in folate biosynthesis. Structure 15:1014–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Handley SF, Frick DN, Bullions LC, Mildvan AS, Bessman MJ. 1996. Escherichia coli orf17 codes for a nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase member of the MutT family of proteins. Cloning, purification, and characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem 271:24649–24654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haussmann C, Rohdich F, Lottspeich F, Eberhardt S, Scheuring J, Mackamul S, Bacher A. 1997. Dihydroneopterin triphosphate epimerase of Escherichia coli: purification, genetic cloning, and expression. J Bacteriol 179:949–951. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.949-951.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pribat A, Blaby IK, Lara-Núñez A, Gregory JF III, de Crécy-Lagard V, Hanson AD. 2010. FolX and FolM are essential for tetrahydromonapterin synthesis in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 192:475–482. doi: 10.1128/JB.01198-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.