ABSTRACT

Lung infections with multiresistant pathogens are a major problem among patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF). N-Chlorotaurine (NCT), a microbicidal active chlorine compound with no development of resistance, is well tolerated upon inhalation. The aim of this study was to investigate the in vitro bactericidal and fungicidal activity of NCT in artificial sputum medium (ASM), which mimics the composition of CF mucus. The medium was inoculated with bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, including some methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA] strains, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli) or spores of fungi (Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus terreus, Candida albicans, Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium boydii, Lomentospora prolificans, Scedosporium aurantiacum, Scedosporium minutisporum, Exophiala dermatitidis, and Geotrichum sp.), to final concentrations of 107 to 108 CFU/ml. NCT was added at 37°C, and time-kill assays were performed. At a concentration of 1% (10 mg/ml, 55 mM) NCT, bacteria and spores were killed within 10 min and 15 min, respectively, to the detection limit of 102 CFU/ml (reduction of 5 to 6 log10 units). Reductions of 2 log10 units were still achieved with 0.1% (bacteria) and 0.3% (fungi) NCT, largely within 10 to 30 min. Measurements by means of iodometric titration showed oxidizing activity for 1, 30, 60, and >60 min at concentrations of 0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, and 1.0% NCT, respectively, which matches the killing test results. NCT demonstrated broad-spectrum microbicidal activity in the milieu of CF mucus at concentrations ideal for clinical use. The microbicidal activity of NCT in ASM was even stronger than that in buffer solution; this was particularly pronounced for fungi. This finding can be explained largely by the formation, through transhalogenation, of monochloramine, which rapidly penetrates pathogens.

KEYWORDS: N-chlorotaurine, antiseptic, antimicrobial, anti-infective, cystic fibrosis, lung

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF), also known as mucoviscidosis, is a genetic disease attributed to a mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which codes for an ATP-dependent chloride channel belonging to the ATP binding cassette transporter family (1). More than 120 different mutations of the CFTR gene are known, definitely causing milder or more severe disease (2). The most abundant mutation is the ΔF508 mutation (lack of phenylalanine at position 508) (2, 3). The disturbed chloride transport causes less water secretion of the exocrine glands and thus less hydration of all of their products. Lung function is particularly affected by the viscous mucus obstructing the airways (4). Impairment of mucociliary clearance and the nutritive properties of the mucus trigger the growth of pathogens and thus lung infections. This leads to further tissue destruction and chronic infection and inflammation of the bronchopulmonary system, which is the main cause of the limited survival of CF patients (4).

Important organisms related to chronic pulmonary infections in CF patients are Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5, 6). They can persist for a long time, i.e., 6 to 70 months, in the CF lung and thereby adapt to their specific environment (7, 8). Staphylococcus aureus, for instance, forms small colony variants that may evade the defense system and are associated with greater resistance to antibiotics (9). The latter is also induced by the repeated antimicrobial treatment required for these patients. As a consequence, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) emerges, followed by P. aeruginosa, which typically forms alginate biofilms and frequently displays multidrug resistance (4). Besides these prevailing pathogens, numerous other bacteria and also fungi have been associated with infections (4, 8). Regarding the latter, filamentous fungi, mainly Aspergillus fumigatus, Scedosporium apiospermum, and Aspergillus terreus, have been associated with deterioration of lung function (10–12); Candida albicans is thought to be mostly commensal (11), although it may cause allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis or disseminated mycosis in immunosuppressed patients (13). Other species, such as Exophiala dermatitidis and other Scedosporium and Aspergillus species, may also cause lung infections in CF (11, 14, 15).

A new causative treatment for CF (ivacaftor) activates the chloride channel of the CFTR protein (16). This approach, however, is beneficial for only some patients, mainly those suffering from certain mutations (especially class III) (4). Inhalation therapy with antibiotics and antifungals is also performed, since high local concentrations can be reached with absent or reduced systemic adverse effects (17). However, lung infections and colonizations with multiresistant pathogens and polymicrobial infections and colonizations are still major problems. Innovations to overcome the resistance problem and effectively target virulent microorganisms are urgently needed. One possibility is inhalation of N-chlorotaurine (NCT) (Cl-HN-CH2-CH2-SO3Na), an endogenous mild oxidant belonging to the class of chloramines (18, 19). It is produced by activated human granulocytes and monocytes as a main component of the long-lived oxidants (20, 21), and it can be synthesized chemically as a sodium salt (18) and applied as a very well tolerated antiseptic to different body regions, including sensitive ones like the eye and hollow organs (22, 23). As an active chlorine compound, it is microbicidal against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa, and it does not induce resistance because of the multiple target molecules in pathogens (18, 24); this has been confirmed for NCT and its analogue dichlorodimethyltaurine in multiple-passage studies with bacteria (25, 26). NCT is also effective against bacteria in biofilms (27–29).

Because of the mild activity and high tissue tolerability of NCT, inhalation treatment with 1% (10 mg/ml, 55 mM) NCT solution appears to be safe, as demonstrated in two studies with pigs and one with mice, with repeated inhalations via a nebulizer over periods of 4 h and 3 weeks, respectively (30–32). In pigs, lung function parameters, including arterial pressure of oxygen, alveoloarterial differences in oxygen partial pressure, and pulmonary arterial pressure, revealed no differences between 1% NCT and placebo (0.9% saline). The same was true for histological and ultrastructural investigations, and the surfactant function remained intact (30, 32). In mice, after 3 weeks of inhalation, no differences from placebo were found with 1% NCT (31). The animals showed normal behavior and increases in weight over time, and there were no signs of increased mucus secretion or bronchial obstruction in histological analyses. No systemic absorption of NCT and no topical accumulation of the substance were found (30, 31). Very recently, once-daily inhalation of 1% NCT for 5 days proved to be safe and very well tolerated, compared to 0.9% NaCl, in healthy volunteers in a phase I clinical trial (12 subjects per group) (R. Arnitz, M. Stein, P. Bauer, B. Lanthaler, B. Baumgartner, H. Jamnig, S. Scholl-Bürgi, K. Stempfl-Al-Jazrawi, H. Ulmer, S. Embacher-Aichhorn, and M. Nagl, unpublished data). On the basis of these encouraging results, topical application of NCT to treat bronchopulmonary infections, e.g., in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and CF, appears interesting. Of note, NCT also exerts anti-inflammatory effects, via downregulation of numerous proinflammatory cytokines (mediated by decreases in nuclear factor κB levels) and upregulation of hemoxygenase-1 (33, 34), and termination of inflammation after the inactivation of invading pathogens is thought to be one of its major functions in the human defense system (21). We have seen hints of such effects in clinical studies with NCT in the outer ear and paranasal sinuses (35, 36), and a combination of antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities could be of advantage in the treatment of lung diseases.

It was the aim of this study to investigate the in vitro bactericidal and fungicidal activity of NCT in artificial sputum medium (ASM), which mimics the viscous mucus of CF patients. Generally, the activity of antiseptics is impaired in the presence of organic material, but NCT is an exception to this rule and generally caused more rapid killing of microorganisms in body fluids and proteinaceous solutions in previous studies (22, 23, 37).

RESULTS

Killing of bacteria.

As expected, NCT showed concentration-dependent killing of bacteria and fungi in ASM. A concentration of 1% killed all bacterial strains to below or nearly at the detection limit of 100 CFU/ml within 10 min, while this effect was achieved after 15 to 30 min with 0.3% NCT. With 0.1%, a reduction in CFU per milliliter of 2 log10 units occurred within 30 min for all strains except for P. aeruginosa, for which 90 min was needed for a reduction in CFU per milliliter of 2.31 ± 0.19 log10 units. No further reduction in CFU per milliliter with 0.1% NCT was found within 120 min, except for S. aureus Smith diffuse, for which the reduction increased from 1.68 ± 0.08 log10 units after 30 min to 2.68 ± 0.04 log10 units after 60 min and 2.93 ± 0.09 log10 units after 90 min (mean ± standard deviation [SD], n = 3; P < 0.01). In Fig. 1, the first 30 min of the killing curves are depicted for ATCC strains of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli and MRSA strain 43300. The additional strains of S. aureus (Smith diffuse and clinical isolates of MRSA) showed curves almost identical to that of MRSA strain 43300. The activity of 1% NCT, summing up the whole course of killing (i.e., bactericidal activity [BA] values [38]), is presented in Table 1; higher values indicate greater microbicidal activity.

FIG 1.

Killing of S. aureus ATCC 25923 (A), P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (B), E. coli ATCC 11229 (C), and MRSA ATCC 43300 (D) by 0.1% (▲), 0.3% (■), and 1.0% (●) NCT in ASM at 37°C. Controls were in phosphate buffer (◆) and ASM (▼) without NCT (dashed lines). The data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3). The detection limit was 2 log10 units. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, versus ASM control, by one-way ANOVA. a, P < 0.01, 1.0% versus 0.3% NCT; b, P < 0.01, 0.3% versus 0.1% NCT, by one-way ANOVA.

TABLE 1.

Bactericidal activity of 1% NCT in ASM and phosphate buffer at pH 7 and 37°C

| Species | BA value (mean ± SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| In ASM | In PO4a | |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0,03 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 1.41 ± 0.28 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| E. coli ATCC 11229 | 2.14 ± 0.46 | 0.36 ± 0.04 |

| S. aureus Smith diffuse | 1.07 ± 0.15 | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| MRSA ATCC 43300 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | ND |

| MRSA 509 | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| MRSA 435d | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| MRSA 152/14 | 1.35 ± 0.14 | ND |

| MRSA 7/15 | 1.27 ± 0.10 | ND |

| MRSA 32/15 | 1.27 ± 0.11 | ND |

| MRSA 65/15 | 1.25 ± 0.09 | ND |

| MRSA 82/15 | 1.32 ± 0.14 | ND |

| MRSA 108/15 | 1.24 ± 0.12 | ND |

Killing of fungi.

Similar to bacteria, all tested spores of fungi were killed by 1% NCT to below the detection limit of 100 CFU/ml within 15 min (30 min for Scedosporium minutisporum). The same effect was achieved with 0.5% NCT after 30 to 60 min (15 min for C. albicans and 120 min for A. terreus). With 0.3% NCT, reductions of ≥2 log10 units were seen with all molds after 15 min, but no reductions to the limit were seen within 120 min. C. albicans was more susceptible, and living cells were not detectable after 60 min with 0.3% NCT. Figure 2 shows the killing curves for C. albicans, A. fumigatus, A. terreus, and S. apiospermum. The remaining molds behaved very similarly to A. fumigatus and S. apiospermum. The fungicidal activity values for 1% NCT in ASM were only slightly lower than the BA values, as can be seen in Table 2.

FIG 2.

Killing of C. albicans ATCC 90028 (A), A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 (B), A. terreus ATCC 3633 (C), and S. apiospermum IHEM 21170 (D) by 0.3% (■), 0.5% (▼), and 1.0% (●) NCT in ASM at 37°C. Controls were in phosphate buffer (◆) and ASM (▼) without NCT (dashed lines). The data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3). The detection limit was 2 log10 units. **, P < 0.01, versus ASM control, by one-way ANOVA. a, P < 0.01, 1.0% versus 0.5% NCT; b, P < 0.01, 0.5% versus 0.3% NCT, by one-way ANOVA.

TABLE 2.

Fungicidal activity of 1% NCT in ASM and phosphate buffer at pH 7 and 37°C

| Species | BA value (mean ± SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| In ASM | In PO4a | |

| C. albicans ATCC 90028 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.0177 ± 0.0018 |

| A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.0087 ± 0.0020 |

| A. terreus ATCC 3633 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.0087 ± 0.0010 |

| S. apiospermum IHEM 21170 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.0031 ± 0.0002 |

| S. boydii isolate M36 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.0046 ± 0.0004 |

| L. prolificans IHEM 21176 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.0023 ± 0.0001 |

| S. aurantiacum V041-53 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | ND |

| S. minutisporum IHEM 21148 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | ND |

| E. dermatitidis CBS 207.35 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | ND |

| Geotrichum isolate 267 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.0055 ± 0.0008 |

Oxidative activity of NCT in ASM.

The oxidative capacity of 1%, 0.5%, 0.3%, and 0.1% NCT decreased to zero within >60 min, 60 min, 30 min, and 3 min, respectively, in ASM (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Oxidative capacity (COX) of 1.0% (●), 0.5% (▼), 0.3% (■), and 0.1% (▲) NCT in ASM, measured by iodometric titration. The data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3). P values were <0.01 for all curves.

Comparison of bactericidal and fungicidal activities of NCT in ASM and phosphate buffer.

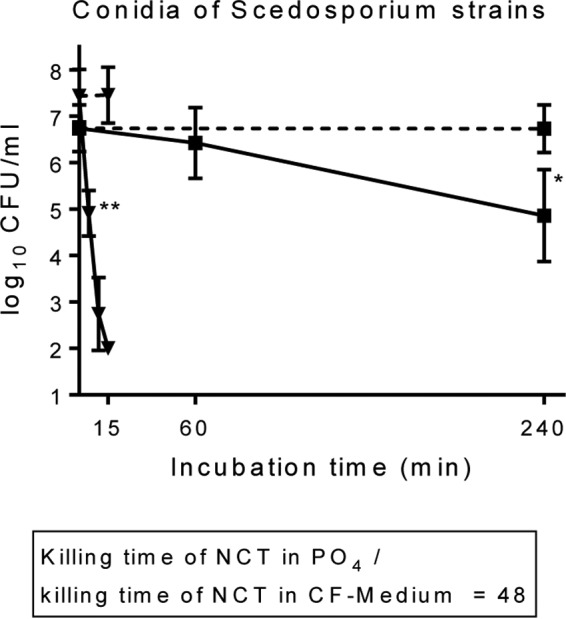

Comparisons were made with our previous data from killing assays performed in phosphate buffer (39–43). Remarkably, the microbicidal activities of 1% NCT in ASM were higher throughout than those in phosphate buffer at the test pH values of 6.9 to 7.1. The BA values measured in ASM were 2- to 4-fold higher than those measured in phosphate buffer for bacteria and 40- to 180-fold higher than those measured in phosphate buffer for fungi (Tables 1 and 2). As an impressive example, the time to achieve 2-log10 reductions in CFU against S. apiospermum IHEM 21170, Lomentospora prolificans IHEM 21176, and Scedosporium boydii in ASM (5 min) was approximately 48 times shorter than in phosphate buffer (240 min) (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Comparison of the fungicidal activities of 1% NCT against conidia of S. apiospermum IHEM 21170, Scedosporium boydii, and Lomentospora prolificans IHEM 21176 in ASM (▼) and phosphate buffer (■) at 37°C and pH of 7.0 ± 0.1. Respective controls were without NCT (dashed lines). Values are summarized from three independent experiments for each strain as means ± SDs (n = 9). P values were <0.01 for 1% NCT in ASM versus 1% NCT in phosphate for all time points except zero. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, versus control without NCT.

DISCUSSION

The bactericidal and fungicidal activity of NCT in a medium representative of the viscous mucus of CF patients has been proven in this study. Similar to findings with other organic materials (26, 42, 44), the activity in ASM was even stronger than that in buffer solutions without chlorine-consuming molecules (39, 40, 42, 43). This effect was particularly remarkable with fungi, leading to approximately 50-fold more rapid killing. Although this is initially surprising, an easy explanation can be given. The active chlorine atom of NCT not only is reduced and inactivated in the presence of organic material but also is partly transferred to amino groups of the organic material, thereby forming the corresponding chloramines in equilibrium (20, 26, 42, 45). In particular, transhalogenation from NCT to ammonium, which forms the more lipophilic, better penetrating, and stronger microbicidal monochloramine (NH2Cl), has been considered causative (22, 46). As a first consequence, this remarkable increase in the microbicidal activity of NCT in human body fluids and exudates enables the clinical application of a mildly oxidizing compound, avoiding the irritative adverse effects of stronger reactive antiseptics (23, 30, 37). Moreover, the superior microbicidal activity of strong active halogen compounds, compared to NCT, has been found to be reversed in peptone solution, because of the high levels of halogen consumption of the former (37, 47). Therefore, NCT seems to be more suitable for body fluids or exudates with high protein loads (23, 37).

As a second consequence, the marked difference between bactericidal activity and fungicidal activity of NCT in plain phosphate buffer is minimized in CF medium. The recently introduced BA values allow a very good survey and render such trends immediately visible (38). The broad-spectrum activity of NCT is unsurprising, taking into account the oxidizing mechanism of action, with numerous sites of attack (22, 23).

In a comparison of the oxidizing activity with the microbicidal activity in ASM, however, one item was surprising. While the oxidative capacities of 1% and 0.5% NCT were present for longer times than those required for killing to the detection limit, this was not the case with 0.1% and partly with 0.3% NCT (Fig. 3); levels of test bacteria were not reduced by 0.1% NCT before the oxidative capacity had vanished (Fig. 1). Explanations remain speculative. Delayed killing by intracellular active chlorine levels is imaginable, as are synergistic effects with residual antimicrobial substances (such as lysozyme and immunoglobulins) in ASM, derived from its hen egg compounds (48). Nevertheless, for clinical applications, including inhalation, we recommend the concentration of 1%, which is well tolerated (30–32) and demonstrates better microbicidal activity than lower concentrations.

Limits of this study include the ASM itself, which is standard and not individualized for each patient, and thus in vivo deviations are expected. Furthermore, the repeated applications in vivo, by irrigation or by inhalation, could not be matched in vitro. Hyphae were not investigated here; however, their susceptibility is similar to that of conidia, as we saw in previous studies (39, 42). Finally, the in vivo efficacy of NCT can be shown only in clinical trials.

Regarding cystic fibrosis, inhalation therapy with NCT can be conceived. To date, tolerability studies with repeated dosing within 1 day in pigs and within 3 weeks in mice have revealed encouraging results, with no hints of severe side effects, with 1% (10 mg/ml) NCT (30–32). In a placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase I clinical study with humans (12 healthy volunteers per group), using once-daily inhalation of 1% NCT versus 0.9% NaCl for 5 days, NCT was well tolerated (R. Arnitz et al., unpublished). With respect to clinical efficacy, the main advantages of NCT were broad-spectrum microbicidal activity against virulent pathogens without the development of resistance, inactivation of toxins, an absence of toxic decay products and allergic reactions because of the endogenous nature of NCT, and anti-inflammatory effects (22, 23, 33, 34).

In conclusion, the microbicidal activity of NCT is stronger in a setting of CF mucus than in buffer solution. This is of interest for possible NCT inhalation for treatment or prophylaxis of bronchopulmonary infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

N-Chlorotaurine (NCT) (molecular mass, 181.57 g/mol; lot 2015-02-05) was prepared as a crystalline sodium salt at pharmaceutical grade in our laboratory, as reported previously (18), stored at −20°C, and freshly dissolved in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 10%, 5%, 3%, or 1% for each experiment. These stock solutions were diluted 10-fold in artificial sputum medium (ASM) at time zero of the killing tests, to final concentrations of 1.0%, 0.5%, 0.3%, or 0.1%. Phosphate buffer (0.1 M), potassium iodide, and tryptic soy broth were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Artificial sputum medium.

To imitate the viscous mucus of CF patients, the ASM recipe described by Kirchner et al. was used (49). The ASM contained the amino acids dl-alanine, dl-methionine, l-arginine, l-asparagine, l-aspartic acid, l-cysteine, l-glutamine, l-glutamic acid, l-histidine, l-isoleucine, l-leucine, l-lysine, l-phenylalanine, l-proline, l-serine, l-threonine, l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, and l-valine, purchased from Merck, Carl Roth GmbH (Karlsruhe, Germany), or Sigma-Aldrich GmbH (Vienna, Austria). Additional contents were egg yolk emulsion (Roth), mucin (type II) from porcine stomach (Sigma), salmon sperm DNA (Roth), diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) (Sigma), sodium chloride, and potassium chloride (Merck). The ASM was prepared exactly as described (49), with the difference that it was aliquoted and frozen at −20°C instead of undergoing sterile filtration at the end. Before use, the aliquots were thawed in a water bath at 37°C. The pH was adjusted to 6.9 (49). Sterile filtration, which requires special equipment and long times because of clogging, was not deemed necessary for our application. We actually found no contamination with microorganisms in our killing assays, including the controls without NCT.

Microorganisms.

Bacteria deep frozen for storage were grown on Columbia agar plates (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) and subcultivated overnight in tryptic soy broth (Merck) at 37°C. Subsequently, they were washed twice in 0.9% saline before use. Strains used were S. aureus ATCC 25923, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 11229, S. aureus Smith diffuse (50), MRSA ATCC 43300, and clinical isolates MRSA 509, MRSA 435d, MRSA 152/14 (Panton-Valentine leukocidin [PVL] positive and resistant to fusidic acid), MRSA 7/15 (resistant to macrolides and clindamycin), MRSA 32/15 (resistant to macrolides, clindamycin, and moxifloxacin), MRSA 65/15 (PVL positive and resistant to macrolides, clindamycin, and gentamicin), MRSA 82/15 (resistant to moxifloxacin), and MRSA 108/15 (resistant to macrolides, clindamycin, and gentamicin).

Fungi were grown on Sabouraud agar (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) for 24 h (C. albicans ATCC 90028) or 72 h (A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 and A. terreus ATCC 3633) or on Scedosporium-selective agar (51) for 10 to 20 days (S. apiospermum IHEM 21170, Scedosporium boydii [clinical isolate from cystic fibrosis, from Austria; internal no. M36 in our laboratory], Lomentospora prolificans IHEM 21176, Scedosporium aurantiacum AZN_NMR-V041-53, and Scedosporium minutisporum FMR 8610 and IHEM 21148) or 14 days (E. dermatitidis CBS 207.35 and Geotrichum [clinical isolate from cystic fibrosis, from Austria; internal no. 267 in our laboratory]). Suspensions of conidia were gained by harvesting them from the agar plates with 5.0 ml of 0.9% saline plus 0.01% Tween 20, followed by 10-μm filtration (CellTrics; Partec GmbH, Görlitz, Germany) to gain a pure conidial suspension without hyphae and three washing steps with phosphate-buffered saline (39).

Time-kill assays.

All experiments were performed at 37°C in a water bath (39, 40). To 3.6 ml of prewarmed ASM, 40 μl of the respective suspension containing bacteria or fungal spores was added, followed by the addition of 0.4 ml NCT at time zero and vortex-mixing. The final starting concentrations were 3.2 × 106 to 1.3 × 107 CFU/ml for S. aureus, 1.3 × 107 to 9.3 × 107 CFU/ml for P. aeruginosa and E. coli, 4.1 × 107 to 4.0 × 108 CFU/ml for MRSA strains, 5.9 × 107 to 2.5 × 108 CFU/ml for C. albicans, A. fumigatus, and A. terreus, 1.6 × 106 to 5.1 × 107 CFU/ml for Scedosporium spp., and 7.1 × 107 to 2.3 × 108 CFU/ml for L. prolificans, E. dermatitidis, and Geotrichum. The incubation times were 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. At the end of each incubation time, aliquots of 100 μl were diluted in 900 μl of NCT-inactivating solution, consisting of 1% methionine and 1% histidine in distilled water. Aliquots of 50 μl of this solution were spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (bacteria, Aspergillus spp., and C. albicans) or Scedosporium-selective agar (Scedosporium spp., L. prolificans, E. dermatitidis, and Geotrichum sp.) in duplicate, using an automatic spiral plater (model WASP 2; Don Whitley, Shipley, United Kingdom). The detection limit was 100 CFU/ml, taking into account both plates and the previous 10-fold dilution in the inactivating solution. Plates were incubated for 48 h (bacteria) to 72 h (fungi) at 37°C (Mueller-Hinton agar plates) or 30°C (Scedosporium-selective agar plates), and the number of CFU was counted. Plates with no growth or only low CFU counts were grown for up to 5 days (bacteria) or 10 days (fungi). Controls, i.e., plain 0.1 M phosphate buffer and 3.6 ml ASM plus 0.4 ml phosphate buffer, were performed without NCT and showed no reductions in CFU. Inactivation controls, in which NCT was mixed with the inactivators 1% methionine and 1% histidine immediately before the addition of pathogens at low CFU counts, showed full survival of bacteria and fungi; this finding proves rapid and sufficient inactivation. The results of the time-kill experiments in ASM from this study were compared with those of time-kill assays in phosphate buffer from our comprehensive previous studies (39–43).

Oxidative activity of NCT in ASM.

The oxidative capacity was measured by iodometric titration (52). NCT (1 ml of a single 10-fold stock, i.e., 10%, 5%, 3%, or 1%) was added to 9 ml prewarmed ASM at time zero and incubated at 37°C in a water bath, revealing final concentrations of 1% (10 mg/ml), 0.5%, 0.3% or 0.1% NCT. After incubation times of 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 min, aliquots of 1 ml were diluted in 9 ml of distilled water. Then, 200 μl of 50% acetic acid was added, followed by surplus potassium iodide (approximately 100 mg). The formed iodine was titrated with 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate using an automated Titration Manager TIM 960 unit (Radiometer Analytical; Hach Lange GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). The oxidative capacity (in moles per liter) was calculated as thiosulfate consumed (in milliliters) × 0.05/volume of NCT used (in milliliters).

Statistics.

The data are presented as means and SDs of at least three independent experiments. Student's unpaired t test, in cases of two groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple-comparison test, in cases of more than two groups, were used to test for differences between the test and control groups. P values of <0.05 were considered significant for all tests. Calculations were performed with GraphPad Prism 6.01 software (GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

For an improved survey of the microbicidal activity of NCT against the different strains, the recently introduced Integral Method was used, which transforms the whole killing curve (log10 CFU per milliliter versus time) into one value of bactericidal activity (BA) (38). Moreover, the method allows expanded statistical analysis, particularly between killing curves with small differences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Bettina Sartori and Andrea Windisch for providing excellent technical assistance and to Michael Berktold for providing the MRSA strains.

This study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (grant KLI459-B30).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt BZ, Haaf JB, Leal T, Noel S. 2016. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators in cystic fibrosis: current perspectives. Clin Pharmacol 8:127–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison PT, Sanz DJ, Hollywood JA. 2016. Impact of gene editing on the study of cystic fibrosis. Hum Genet 135:983–992. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farinha CM, Matos P. 2016. Repairing the basic defect in cystic fibrosis: one approach is not enough. FEBS J 283:246–264. doi: 10.1111/febs.13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elborn JS. 2016. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 388:2519–2531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00576-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall BC, Elbert A, Petren K, Rizvi S, Fink A, Ostrenga J, Sewall A. 2015. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry: annual data report 2014. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zemanick ET, Hoffman LR. 2016. Cystic fibrosis: microbiology and host response. Pediatr Clin North Am 63:617–636. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depluverez S, Devos S, Devreese B. 2016. The role of bacterial secretion systems in the virulence of Gram-negative airway pathogens associated with cystic fibrosis. Front Microbiol 7:1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamath KS, Kumar SS, Kaur J, Venkatakrishnan V, Paulsen IT, Nevalainen H, Molloy MP. 2015. Proteomics of hosts and pathogens in cystic fibrosis. Proteomics Clin Appl 9:134–146. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahl BC, Duebbers A, Lubritz G, Haeberle J, Koch HG, Ritzerfeld B, Reilly M, Harms E, Proctor RA, Herrmann M, Peters G. 2003. Population dynamics of persistent Staphylococcus aureus isolated from the airways of cystic fibrosis patients during a 6-year prospective study. J Clin Microbiol 41:4424–4427. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4424-4427.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimon B, Carrere J, Vinatier JF, Chazalette JP, Chabasse D, Bouchara JP. 2000. Clinical significance of Scedosporium apiospermum in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 19:53–56. doi: 10.1007/s100960050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pihet M, Carrere J, Cimon B, Chabasse D, Delhaes L, Symoens F, Bouchara JP. 2009. Occurrence and relevance of filamentous fungi in respiratory secretions of patients with cystic fibrosis: a review. Med Mycol 47:387–397. doi: 10.1080/13693780802609604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Symoens F, Knoop C, Schrooyen M, Denis O, Estenne M, Nolard N, Jacobs F. 2006. Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection in a cystic fibrosis patient after double-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 25:603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhary A, Agarwal K, Kathuria S, Gaur SN, Randhawa HS, Meis JF. 2014. Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis due to fungi other than Aspergillus: a global overview. Crit Rev Microbiol 40:30–48. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.754401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gungor O, Tamay Z, Guler N, Erturan Z. 2013. Frequency of fungi in respiratory samples from Turkish cystic fibrosis patients. Mycoses 56:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haase G, Skopnik H, Groten T, Kusenbach G, Posselt HG. 1991. Long-term fungal cultures from sputum of patients with cystic fibrosis. Mycoses 34:373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong T, Ramsey BW. 2016. New therapeutic approaches to modulate and correct cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Pediatr Clin North Am 63:751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sermet-Gaudelus I, Le Cocguic Y, Ferroni A, Clairicia M, Barthe J, Delaunay JP, Brousse V, Lenoir G. 2002. Nebulized antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Drugs 4:455–467. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200204070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottardi W, Nagl M. 2002. Chemical properties of N-chlorotaurine sodium, a key compound in the human defence system. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 335:411–421. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zgliczynski JM, Stelmaszynska T, Domanski J, Ostrowski W. 1971. Chloramines as intermediates of oxidation reaction of amino acids by myeloperoxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta 235:419–424. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grisham MB, Jefferson MM, Melton DF, Thomas EL. 1984. Chlorination of endogenous amines by isolated neutrophils. J Biol Chem 259:10404–10413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcinkiewicz J. 1997. Neutrophil chloramines: missing links between innate and acquired immunity. Immunol Today 18:577–580. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(97)01161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottardi W, Nagl M. 2010. N-Chlorotaurine, a natural antiseptic with outstanding tolerability. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:399–409. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottardi W, Debabov D, Nagl M. 2013. N-Chloramines: a promising class of well-tolerated topical anti-infectives. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1107–1114. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02132-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnitz R, Sarg B, Ott HW, Neher A, Lindner H, Nagl M. 2006. Protein sites of attack of N-chlorotaurine in Escherichia coli. Proteomics 6:865–869. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Lima L, Friedman L, Wang L, Xu P, Anderson M, Debabov D. 2012. No decrease in susceptibility to NVC-422 in multiple-passage studies with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2753–2755. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05985-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagl M, Gottardi W. 1996. Enhancement of the bactericidal efficacy of N-chlorotaurine by inflammation samples and selected N-H compounds. Hyg Med 21:597–605. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammann C, Fille M, Hausdorfer J, Nogler M, Nagl M, Coraca-Huber DC. 2014. Influence of poly-N-acetylglucosamine in the extracellular matrix on N-chlorotaurine mediated killing of Staphylococcus epidermidis. New Microbiol 37:383–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coraca-Huber DC, Ammann C, Fille M, Hausdorfer J, Nogler M, Nagl M. 2014. Bactericidal activity of N-chlorotaurine against biofilm forming bacteria grown on metal discs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2235–2239. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02700-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcinkiewicz J, Strus M, Walczewska M, Machul A, Mikolajczyk D. 2013. Influence of taurine haloamines (TauCl and TauBr) on the development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm: a preliminary study. Adv Exp Med Biol 775:269–283. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6130-2_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geiger R, Treml B, Pinna A, Barnickel L, Prossliner H, Reinstadler H, Pilch M, Hauer M, Walther C, Steiner HJ, Giese T, Wemhöner A, Scholl-Bürgi S, Gottardi W, Arnitz R, Sergi C, Nagl M, Löckinger A. 2009. Tolerability of inhaled N-chlorotaurine in the pig model. BMC Pulmon Med 9:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagl M, Eitzinger C, Dietrich H, Anliker M, Reinold S, Gottardi W, Hager T. 2013. Tolerability of inhaled N-chlorotaurine versus sodium chloride in the mouse. J Med Res Pract 2:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwienbacher M, Treml B, Pinna A, Geiger R, Reinstadler H, Pircher I, Schmidl E, Willomitzer C, Neumeister J, Pilch M, Hauer M, Hager T, Sergi C, Scholl-Bürgi S, Giese T, Löckinger A, Nagl M. 2011. Tolerability of inhaled N-chlorotaurine in an acute pig streptococcal lower airway inflammation model. BMC Infect Dis 11:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim C, Cha YN. 2014. Taurine chloramine produced from taurine under inflammation provides anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects. Amino Acids 46:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcinkiewicz J, Kontny E. 2014. Taurine and inflammatory diseases. Amino Acids 46:7–20. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neher A, Fischer H, Appenroth E, Lass-Flörl C, Mayr A, Gschwendtner A, Ulmer H, Gotwald TF, Gstöttner M, Kozlov V, Nagl M. 2005. Tolerability of N-chlorotaurine in chronic rhinosinusitis applied via YAMIK catheter. Auris Nasus Larynx 32:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neher A, Gstöttner M, Nagl M, Scholtz A, Gunkel AR. 2007. N-Chlorotaurine: a new safe substance for postoperative ear care. Auris Nasus Larynx 34:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottardi W, Klotz S, Nagl M. 2014. Superior bactericidal activity of N-bromine compounds compared to their N-chlorine analogues can be reversed under protein load. J Appl Microbiol 116:1427–1437. doi: 10.1111/jam.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottardi W, Pfleiderer J, Nagl M. 2015. The Integral Method, a new approach to quantify bactericidal activity. J Microbiol Methods 115:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lackner M, Binder U, Reindl M, Gönül B, Fankhauser H, Mair C, Nagl M. 2015. N-Chlorotaurine exhibits fungicidal activity against therapy-refractory Scedosporium species and Lomentospora prolificans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6454–6462. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00957-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martini C, Hammerer-Lercher A, Zuck M, Jekle A, Debabov D, Anderson M, Nagl M. 2012. Antimicrobial and anticoagulant activity of N-chlorotaurine (NCT), N,N-dichloro-2,2-dimethyltaurine (NVC-422) and N-monochloro-2,2-dimethyltaurine (NVC-612) in human blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1979–1984. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05685-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagl M, Hengster P, Semenitz E, Gottardi W. 1999. The postantibiotic effect of N-chlorotaurine on Staphylococcus aureus: application in the mouse peritonitis model. J Antimicrob Chemother 43:805–809. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagl M, Lass-Flörl C, Neher A, Gunkel AR, Gottardi W. 2001. Enhanced fungicidal activity of N-chlorotaurine in nasal secretion. J Antimicrob Chemother 47:871–874. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagl M, Gruber A, Fuchs A, Lell C, Lemberger EM, Borg-von Zepelin M, Würzner R. 2002. Impact of N-chlorotaurine on viability and production of secreted aspartyl proteinases of Candida spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1996–1999. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1996-1999.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagl M, Pfausler B, Schmutzhard E, Fille M, Gottardi W. 1998. Tolerance and bactericidal action of N-chlorotaurine in a urinary tract infection by an omniresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Zentralbl Bakteriol 288:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0934-8840(98)80043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas EL, Grisham MB, Jefferson MM. 1986. Preparation and characterization of chloramines. Methods Enzymol 132:569–585. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(86)32042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gottardi W, Arnitz R, Nagl M. 2007. N-Chlorotaurine and ammonium chloride: an antiseptic preparation with strong bactericidal activity. Int J Pharm 335:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottardi W, Nagl M. 2013. Active halogen compounds and proteinaceous material: loss of activity of topical antiinfectives by halogen consumption. J Pharm Pharmacol 65:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedrani L, Helloin E, Guyot N, Rehault-Godbert S, Nys Y. 2013. Passive maternal exposure to environmental microbes selectively modulates the innate defences of chicken egg white by increasing some of its antibacterial activities. BMC Microbiol 13:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirchner S, Fothergill JL, Wright EA, James CE, Mowat E, Winstanley C. 2012. Use of artificial sputum medium to test antibiotic efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in conditions more relevant to the cystic fibrosis lung. J Vis Exp (64):e3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arizono T, Umeda A, Amako K. 1991. Distribution of capsular materials on the cell wall surface of strain Smith diffuse of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 173:4333–4340. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4333-4340.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rainer J, Kaltseis J, de Hoog SG, Summerbell RC. 2008. Efficacy of a selective isolation procedure for members of the Pseudallescheria boydii complex. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 93:315–322. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jooste PL, Strydom E. 2010. Methods for determination of iodine in urine and salt. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 24:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]