ABSTRACT

Among the viridans group streptococci, the Streptococcus mitis group is the most common cause of infective endocarditis. These bacteria have a propensity to be β-lactam resistant, as well as to rapidly develop high-level and durable resistance to daptomycin (DAP). We compared a parental, daptomycin-susceptible (DAPs) S. mitis/S. oralis strain and its daptomycin-resistant (DAPr) variant in a model of experimental endocarditis in terms of (i) their relative fitness in multiple target organs in this model (vegetations, kidneys, spleen) when animals were challenged individually and in a coinfection strategy and (ii) their survivability during therapy with daptomycin-gentamicin (an in vitro combination synergistic against the parental strain). The DAPr variant was initially isolated from the cardiac vegetations of animals with experimental endocarditis caused by the parental DAPs strain following treatment with daptomycin. The parental strain and the DAPr variant were comparably virulent when animals were individually challenged. In contrast, in the coinfection model without daptomycin therapy, at both the 106- and 107-CFU/ml challenge inocula, the parental strain outcompeted the DAPr variant in all target organs, especially the kidneys and spleen. When the animals in the coinfection model of endocarditis were treated with DAP-gentamicin, the DAPs strain was completely eliminated, while the DAPr variant persisted in all target tissues. These data underscore that the acquisition of DAPr in S. mitis/S. oralis does come at an intrinsic fitness cost, although this resistance phenotype is completely protective against therapy with a potentially synergistic DAP regimen.

KEYWORDS: Streptococcus mitis group, experimental endocarditis, daptomycin, gentamicin, high-level daptomycin resistance, virulence, fitness

INTRODUCTION

Among the viridans group streptococci, the members of the Streptococcus mitis group are the most frequent cause of human infective endocarditis (IE) and the most common cause of the toxic streptococcal bacteremia syndrome seen in immunocompromised hosts (1–8). This organism is often resistant in vitro to β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillin and ceftriaxone (9–16). Moreover, despite uniform in vitro susceptibility to vancomycin, patients treated with this agent have had suboptimal outcomes, likely due to vancomycin tolerance (11). This has raised the notion of using daptomycin (DAP) for the treatment of invasive S. mitis group infections. Recent studies have somewhat dampened the enthusiasm for the latter approach, as many S. mitis group strains have a unique propensity to evolve rapid, durable, and high-level daptomycin resistance (DAPr) in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo (17–19). This study investigated the impact of the acquisition of DAPr upon both the intrinsic fitness and survivability during treatment with DAP of such strains in a model of IE featuring coinfection with a DAP-susceptible (DAPs) parental S. mitis/S. oralis strain and its in vivo-derived DAPr variant.

(This research was presented in part at the American Society for Microbiology Microbe meeting, Boston, MA, 19 June 2016 [20].)

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility testing.

The DAP, penicillin, and gentamicin (GEN) MICs for the two test strains were as follows: the DAPs strain had a DAP MIC of 0.5 μg/ml and was not high-level GEN resistant (GENr; MIC = 8 μg/ml) but was resistant to penicillin and ceftriaxone (MICs = 8 μg/ml and 4 μg/ml, respectively). The DAPr strain exhibited high-level DAPr (MIC > 256 μg/ml), was not high-level GENr (MIC = 8 μg/ml), and showed intermediate resistance to penicillin and susceptibility to ceftriaxone (MICs = 0.5 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively). Of interest, a β-lactam–DAP MIC seesaw effect was observed, paralleling the findings of other studies of DAPr Gram-positive pathogens (21). For example, in the DAPs parental strain, the penicillin MIC was 8 μg/ml, but this decreased to 0.5 μg/ml in the DAPr strain; similarly, the ceftriaxone MIC decreased from 4 in the DAPs parental strain to 1 μg/ml in the DAPr strain.

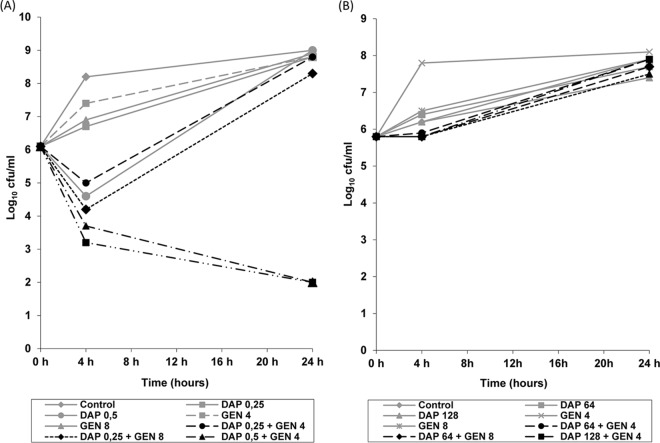

In time-kill synergy studies, only the combination of DAP at 1× MIC plus GEN at either 1/2× MIC or 1× MIC synergistically killed the DAPs parental strain (Fig. 1A). For the DAPr strain, there was no synergistic killing observed with any of the antibiotic combinations (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

(A) Results of time-kill experiments for DAPs strain S.MIT/ORALIS-351 incubated with DAP plus GEN at concentrations of 0.5× MIC and 1× MIC for both antibiotics. (B) Results of time-kill experiments for the DAPr variant incubated with DAP plus GEN at concentrations of 64 μg/ml and 128 μg/ml for DAP and 4 μg/ml and 8 μg/ml for GEN. The numbers in the keys are concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter).

IE coinfection model.

The results of the IE coinfection model with a challenge with an inoculum of 2 × 106 CFU/ml are shown in Table 1. In the absence of antibiotic therapy, both strains induced IE, although the DAPs parental strain was significantly more competitively fit. For example, in terms of vegetation counts, there was a mean difference of ∼4 log10 CFU/g favoring the DAPs parental strain. This difference was even more magnified in terms of kidney and spleen counts, where the DAPr strain was apparently unable to hematogenously seed and/or proliferate within these organs.

TABLE 1.

S. mitis/S. oralis competition in vivo in an experimental coinfection model of endocarditisa

| Study group, strain | Vegetations |

Kidney |

Spleen |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRb | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | |

| Rabbits not treated with antibiotics and sacrificed at 24 h | ||||||

| DAPs strain | 5/5 (100) | 10.1 (9.4–10.2) | 5/5 (100) | 3.2 (2.7–4) | 5/5 (100) | 5.3 (4.5–5.6) |

| DAPr strain | 4/5 (80) | 6.6 (5.7–6.9) | 0/5 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0/5 (0) | 0 (0–0)f |

| P value | 1.000 | .008 | .008 | .008 | .008 | 0.008 |

| Rabbits receiving DAP-GEN and sacrificed after 48 h of treatment | ||||||

| DAPs strain | 0/6 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0/6 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0/6 (0) | 0 (0–0) |

| DAPr strain | 6/6 (100) | 8.5 (6.3–9) | 5/6 (83) | 2.4 (2–2.5) | 3/6 (50) | 1 (0–3.4) |

| P value | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.182 | 0.180 |

Competition was between DAPs and DAPr strains given at an inoculum of 2 × 106 CFU/ml.

IR, infection rate, given as the number of animals with infected valve vegetations, kidney, and spleen/total number of animals (percent).

This reduced competitive fitness was also mirrored when animals were individually challenged with the DAPr strain at the same 2 × 106-CFU/ml inoculum (Table 2). In this scenario, vegetation seeding occurred in all animals, although the median achievable counts were still ∼1.5 log10 CFU/g below the count for the parental strain (Table 1). Similarly, seeding to and proliferation within kidneys and spleen occurred with the individual challenge with the DAPr strain, although this seeding was not uniformly detected in all challenged animals (40% and 60%, respectively).

TABLE 2.

DAPr S. mitis/S. oralis fitness in vivo during challenge in an experimental model of endocarditisa

| Vegetations |

Kidney |

Spleen |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRb | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 of CFU/g tissue |

| 5/5 (100) | 8.6 (7.6–8.9) | 2/5 (40) | 1.4 (0–2.6) | 3/5 (60) | 2.4 (0–3.2) |

The DAPr S. mitis/S. oralis strain was given at an individual inoculum of 2 × 106 CFU/ml. Rabbits were not treated with antibiotics and were sacrificed at 24 h postinfection.

IR, infection rate, given as the number of animals with infected valve vegetations, kidney, and spleen/total number of animals (percent).

To examine the impact of the challenge inoculum on competitive fitness, catheterized animals were cochallenged in parallel with an intravenous (i.v.) inoculum of 2 × 107 CFU/ml of the DAPs and DAPr strains. As seen in Table 3, we saw an outcome very similar to that achieved with the 106-CFU/ml coinfection model described above. Thus, the DAPr strain did infect cardiac vegetations, although it did so at a significantly reduced level compared to that for the DAPs strain. Moreover, even though both the kidneys and the spleen were seeded by the DAPr strain in most rabbits, tissue counts were significantly below those of the DAPs strain.

TABLE 3.

Competitive fitness of DAPs and DAPr strains in vivo during coinfection challenge in an experimental model of endocarditisa

| Strain | Vegetations |

Kidney |

Spleen |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRb | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | IR | Median (IQR) log10 no. of CFU/g tissue | |

| DAPs strain | 5/5 (100) | 8.5 (8.4–8.6) | 5/5 (100) | 5.0 (4.4–5.4) | 5/5 (100) | 4.8 (4.8–4.9) |

| DAPr strain | 5/5 (100) | 6.9 (6.7–7.1) | 3/5 (60) | 1.7 (0.6–1.8) | 4/5 (80) | 1.6 (1.5–2.0) |

| P value | 0.008 | 0.492 | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.008 | |

The challenge inoculum was 2 × 107 CFU/ml. Rabbits were not treated with antibiotics and were sacrificed at 24 h postinfection.

IR, infection rate, given as the number of animals with infected valve vegetations, kidney, and spleen/total number of animals (percent).

Table 1 also details the outcome of combined DAP-GEN therapy in animals coinfected with the DAPs and DAPr strains at a 2 × 106-CFU/ml inoculum. After 48 h of combined treatment, DAPs parental colonies were completely cleared from all target tissues, leaving only DAPr colonies surviving in the three target tissues. All DAPr variants isolated from these target tissues maintained stable, high-level DAPr at the time of sacrifice, as determined by Etest.

DISCUSSION

Garcia-de-la-Maria et al. have previously shown that S. mitis group strains have a unique capacity to evolve stable, high-level DAPr both in vitro and in vivo (17). For example, in a study of 92 S. mitis group clinical isolates, this phenotype was identified in ∼27% of isolates upon DAP passage in vitro (17). We have recently demonstrated that the genetic mechanisms for the development of DAPr in S. mitis/S. oralis involve the acquisition of loss-of-function single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the cdsA and pgsA loci of the organism (22, 23). These genes encode enzymes which are critical in the biosynthetic pathway for cardiolipin (CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyl-synthetase and CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyl-transferase, respectively). These mutations are associated with a complete loss of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol production (22, 23). Given the critical roles of both cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol in the mechanism of action of DAP (24, 25), it is plausible that the mutations in the loci mentioned above are the principal drivers of DAPr in our strain after in vivo passage. Of interest, this mechanism of DAPr differs substantially from the mechanisms involved in DAPr in S. aureus (charge repulsion) (26–28) and enterococci (antibiotic diversion for Enterococcus faecalis and charge repulsion for E. faecium) (29, 30). However, little is known about the impacts of DAPr on innate pathogenicity and the antimicrobial response profiles in the S. mitis group.

Many studies have suggested that the acquisition of antibiotic resistance comes with a metabolic fitness cost for the organism (31, 32). This is usually reflected by lower growth rates and/or lower growth yields in vitro for such resistant strains compared with those for their respective antibiotic-susceptible parental strains. However, documentation of the fitness costs of antibiotic resistance using in vivo virulence experiments in terms of its impact on the organism's (i) transmissibility, (ii) persistence and proliferation within target host tissues, or (iii) ability to evade and survive innate or adaptive immune host defenses is relatively infrequent in the literature (31–33). The current study was designed to quantify the effects of the acquisition of DAPr in S. mitis/S. oralis on both intrinsic virulence and survivability during DAP exposures, using a discriminative model of endovascular infection, IE.

A number of interesting observations emerged from this investigation. First, it seems clear that acquisition of genetic perturbations related to DAPr does impact the in vitro and intrinsic in vivo virulence of the DAPr strain in our model of endovascular infection. Of note, the reduction in the in vivo fitness of the DAPr strain was manifest in all target organs in the IE model, although it was particularly evident in kidneys and spleen. This may reflect an enhanced susceptibility of the DAPr strains to neutrophil-based host defenses that are replete in the latter organs and accompany abscess formation. Alternatively, this reduced virulence may imply a defect in the seeding of distant target organs by the DAPr strain, i.e., a perturbation in hematogenous spread from vegetations to these distant organs by non-neutrophil-based mechanisms, such as the elaboration of platelet antimicrobial peptides within cardiac vegetations (34, 35). Second, the apparent in vivo fitness defect of the DAPr strain could not be overcome by merely increasing the challenge inoculum from 106 to 107 CFU/ml. This suggests that the impact of the DAPr strain on intrinsic fitness represents a homogeneous and not a heterogeneous population effect. Third, although the DAPr strain was intrinsically less fit than its parental strain in vivo, DAPr provided the strain with uniform protection against treatment with a combination of DAP-GEN, which synergistically killed the parental isolate.

Garcia-de-la-Maria et al. (17) have previously demonstrated that, in the model of experimental endocarditis caused by strain S.MIT/ORALIS-351, addition of GEN to DAP not only significantly increased the number of vegetations sterilized after 48 h of treatment compared to the number sterilized by DAP alone but also prevented the development of DAPr in 21 of 23 treated rabbits (91%). Although the mechanisms of DAPr in the S. mitis group seem to differ substantially from those involved in DAPr in Staphylococcus aureus and enterococci, as explained above, there is an interest for future study to look into whether combinations of DAP plus β-lactams, such as ampicillin or ceftriaxone, are synergistic against S. mitis and could prevent the development of DAPr. To this point, Yim et al. (19) recently showed that the combination of DAP plus ceftaroline was synergistic and bactericidal against two prototypic S. mitis/S. oralis strains (S.MIT/ORALIS-351 and SF100) in an ex vivo model of simulated endocardial vegetations (SEVs) and also prevented the development of DAPr in both strains.

In conclusion, the acquisition of the DAPr phenotype affects the virulence of S. mitis/S. oralis in experimental IE in terms of a reduction in its in vivo fitness in all target organs, especially kidneys and spleen. However, DAPr variants were able to induce IE, with their survival being amplified in the presence of DAP-GEN combination therapy. Further studies are needed to identify other possibly effective DAP combination therapies that can either prevent the emergence of or enhance the treatment of DAPr S. mitis group variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

We studied a clinically derived parental DAPs S. mitis/S. oralis bloodstream isolate (SMIT-351) from a patient with IE. This strain is virulent in the experimental IE model (17), and it was identified to be an S. mitis strain on the basis of standard biotyping and 16S RNA sequencing. Recently, we have had the results of genome sequencing for this strain, and we discovered that this strain is more likely a member of the closely related species S. oralis, on the basis of average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis of the whole-genome sequence. The strain has therefore been renamed S.MIT/ORALIS-351 and is so listed in GenBank. We also studied a stably high-level DAPr variant strain (strain D6-6; DAP MIC > 256 μg/ml) isolated from the vegetations of a rabbit with experimental IE after 48 h treatment with DAP alone once daily at 6 mg/kg of body weight/day i.v. (17). According to both determination of the optical density at 600 nm by spectrophotometry and formal counts of the number of CFU per milliliter, the mutant strain (DAPr) was less fit than the parent strain (DAPs) over a 24-h time frame in vitro in terms of growth kinetics and yield (data not shown).

Antibiotics.

DAP powder for in vitro testing and animal treatment was supplied by Cubist Pharmaceuticals (Lexington, MA). USP-grade penicillin and gentamicin (GEN) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

In vitro susceptibility assays.

DAP, penicillin, and GEN MICs were determined using the broth microdilution method, according to standard recommendations (36). Susceptibility to DAP was tested in Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml of calcium chloride (CAMHB). Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 served as the quality control strain. DAP MICs were also determined in selected studies by using the Etest method following the manufacturer's recommendations (bioMérieux S.A., Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Time-kill studies.

The time-kill methodology was used to test the activity of DAP plus GEN against S.MIT/ORALIS-351 and its DAPr variant, D6-6, according to previously described criteria (37). A final inoculum of between 5 × 105 and 7 × 105 CFU/ml was used. Prior to inoculation, each tube of fresh CAMHB plus lysed horse blood at a final concentration of 5% was supplemented with DAP alone or in combination with GEN. For the DAPs parental strain, the antibiotic concentrations tested were 1/2× MIC and 1× MIC for both DAP (0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively) and GEN (4 and 8 μg/ml, respectively). For the DAPr strain (DAP MIC > 256 μg/ml), DAP concentrations were adjusted to 64 μg/ml and 128 μg/ml. A tube without antibiotics was used as a growth control. Viability counts were performed at 0, 4, and 24 h as described by Isenberg (38). Drug carryover was addressed by serial dilution plate counting. Bactericidal synergy was defined as a ≥2-log10 decrease in the number of CFU per milliliter between the combination antibiotic and the most active agent alone after 24 h; moreover, the number of surviving organisms in the presence of the combination had to be ≥2 log10 CFU/ml below the starting inoculum. At least one of the drugs had to be present at a concentration that did not significantly affect the growth curve of the test organism when used alone. Bactericidal activity was defined as at least a 3-log10 reduction in the number of CFU per milliliter at 24 h in comparison with the initial inoculum.

In vivo studies. (i) Animal models.

New Zealand White rabbits (body weight, ∼2.5 kg) obtained from local breeding sources were housed in the animal facilities located at the Faculty of Medicine from the University of Barcelona and at LA Biomedical Research Institute. They were provided food and water ad libitum. This research project fulfills the requirements stipulated in Spanish Royal Decree 223/1988 on the protection of animals used in experiments, and it was approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Research of the University of Barcelona. In addition, parallel studies performed at the LA Biomedical Research Institute were approved by its Animal Use Committee (IACUC).

(ii) Human pharmacokinetic simulation studies.

The antibiotics were administered to animals with IE using a computer-controlled infusion pump system designed to simulate human-equivalent serum levels following the administration of DAP at the FDA-approved dose for S. aureus bacteremia (6 mg/kg) (39) and GEN at the recommended synergistic dose for enterococcal IE (1 mg/kg i.v. every 8 h) (40).

The computer-assisted program procedure has three steps: (i) estimation of antibiotic parameters in the rabbit, (ii) application of a mathematical model to determine the infusion rate required for reproducing human-like pharmacokinetics in animals, and (iii) collection of serum samples to check that the antibiotic levels actually achieved in the animals mimic the desired human pharmacokinetic profiles. These studies have been done previously and reported on elsewhere (37, 39).

(iii) In vivo experimental IE model.

Experimental aortic valve IE was induced as described previously (41). In brief, an indwelling polyethylene catheter was inserted through the right carotid artery into the left ventricle in anesthetized animals to induce aortic valve trauma; in addition, two catheters for administration of antibiotics were placed into the inferior vena cava through the jugular vein and tunneled subcutaneously to the interscapular region. The external portion of each jugular catheter was connected to a swivel and then to a computer-controlled infusion pump as previously described (41).

At 24 h after placement of the intracarotid catheter, animals were infected via the marginal ear vein with (i) an inoculum of either DAPs or DAPr strain at 2 × 106 CFU/ml for assessment of fitness, (ii) a mixed inoculum (ratio, ∼1:1) of both strains at 2 × 107 CFU/ml for assessment of fitness at a higher inoculum, or (iii) a mixed inoculum (ratio, ∼1:1) of both strains at 2 × 106 CFU/ml for assessment of antibiotic treatment. One milliliter of blood was obtained at 24 h after infection from animals in all groups plus immediately before the initiation of antimicrobial therapy from animals in the treatment groups to confirm the presence of persistent bacteremia (to indicate the successful induction of IE). A group of nontreated infected animals was sacrificed concurrently, and the bacterial densities in vegetations, kidney, and spleen were calculated (see below). The remainder of the animals underwent antibiotic therapy with DAP-GEN, administered for 48 h via the computer-controlled infusion pump system through the indwelling jugular catheter.

After the completion of treatment, six half-lives (t1/2s) of both antibiotics (DAP and GEN) were allowed to lapse before the animals were sacrificed in order to avoid antibiotic carryover effects from blood to tissue. This translates to 48 h for DAP (t1/2 = 8 h) and 9 h for GEN (t1/2 = 1.5 h). Given the longer half-life of DAP, GEN infusions were continued during the first 15 h. Rabbits were then humanely sacrificed; the heart, spleen, and kidneys were surgically removed; and target tissue samples were obtained: aortic valve vegetations from the heart and tissue samples from the spleen and kidney (41).

Analysis of infected tissues.

Target tissue samples were serially diluted and processed for quantitative culture as described before (17). Tissue homogenates were seeded in parallel on plain brain heart infusion agar (BHIA; Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, England) plates, as well as on BHIA plates containing DAP (8 μg/ml) to individually quantify surviving DAPs versus DAPr colonies. Colonies recovered from DAP-containing BHIA plates were also retested in parallel using the DAP Etest to ensure retention of the DAPr phenotype. Target tissue bacterial counts were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) of the log10 number of CFU per gram of each target tissue. If there was no growth on the quantitative culture plates with tissue homogenates but there was growth in the qualitative culture (for which the rest of the tissue homogenate was cultured in tryptic soy broth for 7 days), that target tissue sample was assigned a value of 2 log10 CFU/g. If there was no growth either in the initial quantitative plate cultures or from the homogenates qualitatively cultured for 7 days, that target tissue sample was assigned a value of 0 and the tissue was considered sterile.

Statistical analysis.

The Fisher exact test was used to compare the rates of sterile target tissues between tissues from animals infected with the DAPr and DAPs strains. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare the values of the log10 number of CFU per gram of target tissues between the different treatment groups. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to the members of the Endocarditis Team of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. We also thank Wessam Abdelhady (LA Biomedical Research Institute) for excellent technical support in the experimental IE studies.

J.M.M. received a personal intensification research grant (number INT15/00168) during 2016 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Madrid, Spain, a personal 80:20 research grant from the Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain, during 2017-19, and grant FIS 02/0322 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Madrid, Spain. P.M.S. was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health (NIAID R01 AI41513 and R01 AI106987). A.S.B. was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID 5RO1 AI039810-19). M.J.R. has received support from the National Institutes of Health (NIAID AI109266 and AI121400).

J.M.M. has received consulting honoraria and/or research grants from AbbVie, BMS, Cubist, Merck, Novartis, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Roche, and ViiV Healthcare. A.S.B. has received research grants from Trellis, ContraFect Corp., and Theravance. C.A.A. has received research funding from Merck, Theravance, Allergan, and The Medicines Company; he is in the speaker's bureaus of Pfizer, Merck, Allergan, and The Medicines Company and has served as a consultant for Theravance, The Medicines Company, Merck, Bayer Global, and Allergan. M.J.R. has received research grants and consulting and/or speaking honoraria from Allergan, Cempra, Merck, The Medicines Company, and Theravance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fowler VG, Scheld WM, Bayer AS. 2015. Endocarditis and intravascular infections, p 990–1028. In Principles and practices of infectious diseases. Elsevier Inc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelburne SA, Sahasrabhojane P, Saldana M, Yao H, Su X, Horstmann N, Thompson E, Flores AR. 2014. Streptococcus mitis strains causing severe clinical disease in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis 20:762–771. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.130953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freifeld AG, Razonable RR. 2014. Viridans group streptococci in febrile neutropenic cancer patients: what should we fear? Clin Infect Dis 59:231–233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelburne SA, Lasky RE, Sahasrabhojane P, Tarrand JT, Rolston KV. 2014. Development and validation of a clinical model to predict the presence of β-lactam resistance in viridans group streptococci causing bacteremia in neutropenic cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis 59:223–230. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed R, Hassall T, Morland B, Gray J. 2003. Viridans streptococcus bacteremia in children on chemotherapy for cancer: an underestimated problem. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 20:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain E, Whitehead S, Castell A, Thomas EE, Speert DP. 2005. Viridans streptococci bacteremia in children with malignancy: relevance of species identification and penicillin susceptibility. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24:563–566. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000164708.21464.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marron A, Carratala J, Gonzalez-Barca E, Fernández-Sevilla A, Alcaide F, Gudiol F. 2000. Serious complications of bacteremia caused by viridans streptococci in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 31:1126–1130. doi: 10.1086/317460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang WT, Chang LY, Hsueh PR, Lu CY, Shao PL, Huang FY, Lee PI, Chen CM, Lee CY, Huang LM. 2007. Clinical features and complications of viridans streptococci bloodstream infection in pediatric hemato-oncology patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 40:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prabhu RM, Piper KE, Baddour LM, Steckelberg JM, Wilson WR, Patel R. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among viridans group streptococci isolates from infective endocarditis patients from 1971-1986 and 1994-2002. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4463–4465. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4463-4465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doern GV, Ferraro MJ, Brueggermann AB, Ruoff KL. 1996. Emergence of high rates of antimicrobial resistance among viridans group streptococci in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40:891–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safdar A, Rolston KV. 2006. Vancomycin tolerance, a potential mechanism for refractory gram-positive bacteria: observational study in patients with cancer. Cancer 106:1815–1820. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu R-B, Lin F-Y. 2006. Effect of penicillin resistance on presentation and outcome of nonenterococcal streptococcal infective endocarditis. Cardiology 105:234–239. doi: 10.1159/000091821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabella C, Murphy D, Drummond-Webb J. 2001. Endocarditis due to Streptococcus mitis with high-level resistance to penicillin and ceftriaxone. JAMA 285:2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonks JR, Dickinson BP, Runarsdottir V. 1999. Endocarditis due to Streptococcus mitis with high-level resistance to penicillin and cefotaxime. N Engl J Med 341:1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han XY, Kamana M, Rolston KV. 2006. Viridans streptococci isolated by culture from blood of cancer patients: clinical and microbiologic analysis of 50 cases. J Clin Microbiol 44:160–165. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.160-165.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez M, Vicente MF, Cercenado E, de Pedro MA, Gómez P, Moreno R, Morón R, Berenguer J. 2001. Diversity among clinical isolates of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus mitis: indication for a PBP1-dependent way to reach high levels of penicillin resistance. Int Microbiol 4:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s10123-001-0040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-de-la-Maria C, Pericas Del Río JM, Castañeda A, Vila-Farrés X, Armero X, Espinal Y, Cervera PA, Soy C, Falces D, Ninot C, Almela S, Mestres M, Gatell CA, Vila JM, Moreno J, Marco A, Miró JM, Hospital Clinic Experimental Endocarditis Study Group. 2013. Early in vitro and in vivo development of high-level daptomycin resistance is common in mitis group streptococci after exposure to daptomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2319–2325. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01921-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akins RL, Katz BD, Monahan C, Alexander D. 2015. Characterization of high-level daptomycin resistance in viridans group streptococci developed upon in vitro exposure to daptomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2102–2112. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04219-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yim J, Smith JR, Singh N, Hallesy J, Garcia de la Maria C, Bayer AS, Mishra NN, Miro JM, Arias CA, Tran TT, Sullam P, Rybak MJ. 2016. Combinations of daptomycin and ceftaroline or gentamicin against Streptococcus mitis in an in vitro model of simulated endocardial vegetations, abstr 2016-5703. Abstr ASM Microbe Meet, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García de la Mária C, Pericás JM, Armero Y, Moreno A, Mishra NN, Rybak MJ, Tran TT, Arias CA, Sullam PM, Xiong YQ, Bayer A, Miró JM. 2016. High-level daptomycin-resistant (DAP-R) Streptococcus mitis is virulent in experimental endocarditis (EE) and enhances survivability during DAP treatment vs. its DAP-susceptible (DAP-S) parental strain, poster P-335. Abstr ASM Microbe Meet, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang SJ, Xiong YQ, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R, Jones T, Bayer AS. 2010. Daptomycin-oxacillin combinations in treatment of experimental endocarditis caused by daptomycin-nonsusceptible strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with evolving oxacillin susceptibility (the “seesaw effect”). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3161–3169. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00487-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra NN, Alvarez DN, Seepersaud R, Tran TT, Garcia-de-la-Maria C, Miro JM, Rybak MJ, Arias CA, Sullam PM, Bayer AS. 2015. Phenotypic and genotypic mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in Streptococcus mitis, abstr C1-1364. Abstr 55th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, San Diego, CA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra NN, Tran TT, Seepersaud R, Garcia-de-la-Maria C, Faull K, Yoon A, Proctor R, Miro JM, Rybak MJ, Bayer AS, Arias CA, Sullam PM. 2017. Perturbations of phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase (CdsA) mediate daptomycin resistance in Streptococcus mitis/oralis by a novel mechanism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02435-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02435-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WR, Bayer AS, Arias CA. 2016. Mechanism of action and resistance to daptomycin in Staphylococcus aureus and enterococci. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6:a026997. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor SD, Palmer M. 2016. The action mechanism of daptomycin. Bioorg Med Chem 24:6253–6258. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra NN, Bayer AS. 2013. Correlation of cell membrane lipid profiles with daptomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1082–1085. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02182-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertsche U, Yang SJ, Kuehner D, Wanner S, Mishra NN, Roth T, Nega M, Schneider A, Mayer C, Grau T, Bayer AS, Weidenmaier C. 2013. Increased cell wall teichoic acid production and d-alanylation are common phenotypes among daptomycin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clinical isolates. PLoS One 13:e67398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang SJ, Mishra NN, Rubio A, Bayer AS. 2013. Causal role of single nucleotide polymorphisms within the mprF gene of Staphylococcus aureus in daptomycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5658–5664. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01184-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra NN, Bayer AS, Tran TT, Shamoo Y, Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W, Guan Z, Arias CA. 2012. Daptomycin resistance in enterococci is associated with distinct alterations of cell membrane phospholipid content. PLoS One 7:e43958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran TT, Munita JM, Arias C. 2015. Mechanism of drug resistance: daptomycin resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1354:32–53. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson DI, Levin BR. 1999. The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol 2:489–493. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson DI, Hughes D. 2010. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol 8:260–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Hal SJ, Jones M, Gosbell IB, Paterson DL. 2011. Vancomycin heteroresistance is associated with reduced mortality in ST239 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus blood stream infections. PLoS One 6:e21217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeaman MR, Bayer AS. 1999. Antimicrobial peptides from platelets. Drug Resist Updat 2:116–126. doi: 10.1054/drup.1999.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeaman MR, Bayer AS. 2006. Antimicrobial peptides versus invasive infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 306:111–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 21st informational supplement. M100-S21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miró JM, García-de la-Mària C, Armero Y, Soy D, Moreno A, del Río A, Almela M, Sarasa M, Mestres CA, Gatell JM, Jiménez de Anta MT, Marco F, Hospital Clinic Experimental Endocarditis Study Group. 2009. Addition of gentamicin or rifampin does not enhance the effectiveness of daptomycin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4172–4177. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00051-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isenberg HD. (ed). 2004. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, 2nd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marco F, García-de la-Mària C, Armero Y, Amat E, Soy D, Moreno A, del Río A, Almela M, Mestres CA, Gatell JM, Jiménez de Anta MT, Miró JM, Hospital Clinic Experimental Endocarditis Study Group. 2008. Daptomycin is effective in treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant and glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2538–2543. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00510-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, Bolger AF, Steckelberg JM, Baltimore RS, Fink AM, O'Gara P, Taubert KA, American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, Anesthesia and Stroke Council. 2015. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miro JM, García-de la-Mària C, Armero Y, de-Lazzari E, Soy D, Moreno A, del Rio A, Almela M, Mestres CA, Gatell JM, Jiménez-de-Anta MT, Marco F, Hospital Clinic Experimental Endocarditis Study Group. 2007. Efficacy of televancin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2373–2377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01266-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]