Abstract

Although large bowel obstruction (LBO) is less common than small bowel obstruction, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality due to delayed diagnosis and/or treatment. Plain radiographs are sufficient to diagnose LBO in a majority of patients. However, further evaluation with multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) has become the standard of care to identify the site, severity, and etiology of obstruction. In this comprehensive review, we illustrate the various causes of LBO emphasizing the role of MDCT in the initial diagnosis and detection of complications along with the tips to differentiate from disease which can mimic LBO.

Keywords: Diverticulitis, large bowel obstruction, multidetector computed tomography, neoplastic, pseudo-obstruction, volvulus

Introduction

Large bowel obstruction (LBO) is an important abdominal emergency that can result in significant morbidity and mortality, especially in cases of acute complete obstruction and/or delayed diagnosis or treatment. Imaging plays a vital role in the management of LBO by identifying the location, degree, and cause of obstruction and also aids in the detection of complications. Plain radiographs are the initial imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with suspected bowel obstruction with computed tomography (CT) being the definitive investigation.

LBO often presents as an emergency that requires early and accurate diagnosis for prompt treatment. Although LBO is 4–5 times less common than small bowel obstructions (SBOs), it account for nearly 2%–4% of all surgical admissions.[1] Clinical diagnosis of LBO depends on four cardinal findings of abdominal pain, constipation or obstipation, abdominal distention, and vomiting if ileocecal valve is incompetent. LBO can be due to various causes and can be classified broadly as neoplastic and nonneoplastic pathologies. The overall most common cause of LBO in adults is colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer, diverticulitis, and volvulus together account for approximately 80%–85% of all LBO cases.[2] Most cases are of neoplastic etiology, with non-neoplastic causes being relatively uncommon. In this article, we present the diagnostic approach to LBO, comprehensive review of various causes of LBO with emphasis on the role of multidetector CT (MDCT) in the initial diagnosis and detection of complications along with a short note on the mimickers of LBO [Table 1].

Table 1.

Causes of large bowel obstruction

Imaging approach

Abdominal radiography, MDCT, and contrast enema are the three commonly used imaging modalities in the evaluation of LBO. Abdominal radiograph is the first imaging performed in suspected cases of bowel obstruction and can diagnose LBO with a sensitivity and specificity of 84% and 72%, respectively.[3] It can also help to differentiate LBO from SBO and in detecting pneumoperitoneum. Supine and erect (or left lateral decubitus) are the routine two views recommended. Normal colonic caliber is variable due to its high distensibility, and for practical purpose cecum >9 cm and rest of the colon >6 cm in diameter is considered as dilated.[4] The presence of colonic air-fluid levels usually indicates an acute mechanical obstruction. The absence of distal rectal gas is not a reliable sign of LBO as it can be seen in colonic ileus as well.

MDCT is the definitive imaging for LBO with a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 93%, respectively.[5,6] It can help in establishing the cause of obstruction by showing luminal, mural, and extramural pathologies and also in early detection of complications such as bowel ischemia, infarction, and perforation. The presence of a transition point with proximal dilated bowel and distal collapsed colon is diagnostic of LBO. After the advent of MDCT and its wide availability, the indications for contrast enema have become very limited. It is helpful in differentiating LBO and pseudo-obstruction, colonic volvulus and to compliment MDCT in equivocal cases of LBO.[3,7]

Neoplastic

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the most common cause of LBOs, representing approximately 60% of all cases.[1] Acute LBO is the initial presentation to approximately 7%–29% of patients with colorectal cancer.[8] In addition, nearly 20% of all colorectal carcinomas are complicated by some degree of obstruction. Over 75% of obstructing colorectal cancers are distal to the splenic flexure, with the Sigmoid colon being the most common location due to its fecal contents and relatively narrow diameter.[1,8] In colorectal cancer, MDCT findings include an enhancing soft tissue mass or an asymmetric and short segment thickening of the colonic wall with shouldering. The dilation of the colon proximal to the tumor helps in identifying the tumor easier [Figure 1]. Complications of LBO secondary to colorectal cancer include infarction which is evidenced by pneumatosis of the affected proximal colon wall. Another complication includes perforation, the most common site being cecum. Dilatation of the cecum to a diameter of 12 cm is considered a risk factor for diastatic perforation.[1] In addition, MDCT can help in the staging of the tumor by demonstrating the extent of the lesion, involvement of adjacent structures, associated lymphadenopathy, and intraperitoneal metastasis.

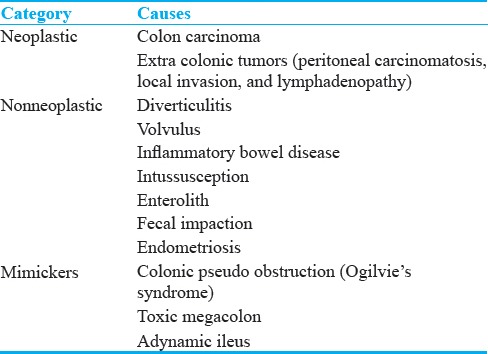

Figure 1.

Colorectal cancer: (a and b) Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography images in a 60-year-old male patient with colorectal cancer presenting with weight loss and chronic abdominal pain demonstrate marked distension of transverse colon and splenic flexure (long arrow in a) with associated short segment mural thickening of proximal descending colon with abrupt transition (short arrow) to a normal appearing descending colon (long arrow in b). The large bowel dilatation and abrupt transition are better depicted on the coronal image (c).

Extracolonic malignancies

Large bowel can become extrinsically compressed resulting in obstruction. It is usually caused by neoplastic spread into the peritoneal cavity by intraperitoneal seeding (as in peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer), direct invasion (from pancreatic, genitourinary malignancies), lymphatic, or hematogenous metastasis.[9,10] MDCT features of extrinsic neoplastic obstruction include mesenteric or omental masses infiltrating the bowel at the site of transition, multifocal disease and known primary extracolonic malignancy [Figures 2 and 3]. However in advances cases, it may be difficult to differentiate from primary colonic tumor with peritoneal spread and histopathological examination will determine the site of origin.[9]

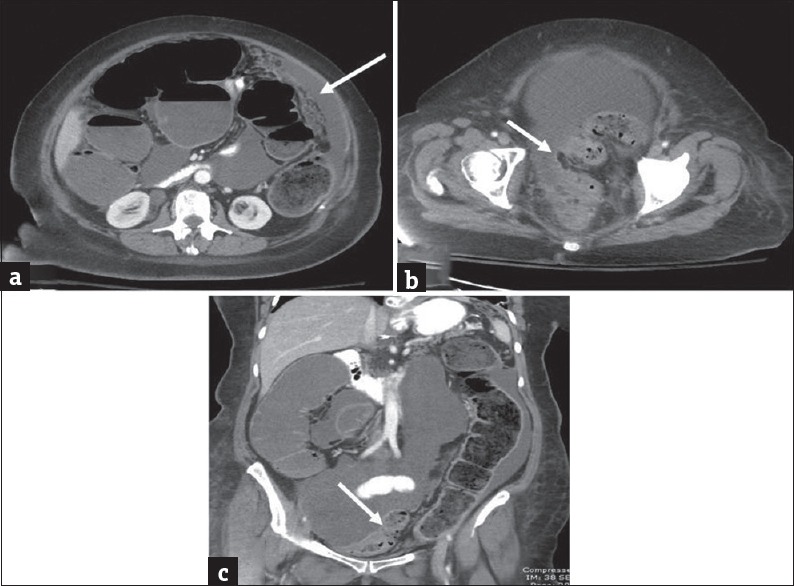

Figure 2.

Extra colonic malignancies: (a and b) Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography images in a 56-year-old female patient with history of ovarian cancer presenting with abdominal distension demonstrate ascites, peritoneal thickening and omental caking consistent with peritoneal carcinomatosis (arrow in a). There is marked distension of the proximal large bowel and fecal loading of the descending colon. The pelvic peritoneal metastatic deposits caused extrinsic narrowing of the sigmoid colon (arrow in b) and accounted for the large bowel obstruction. The large bowel dilatation and transition point in the sigmoid colon are better depicted on the coronal image (c).

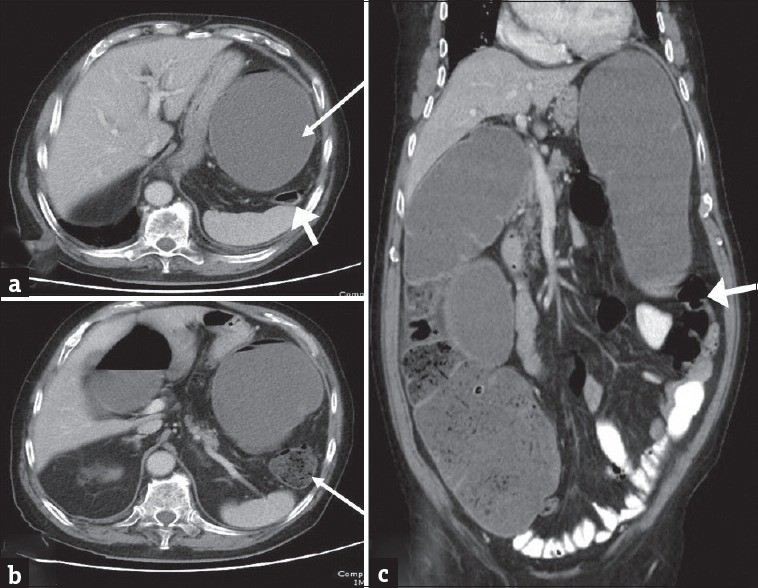

Figure 3.

Extracolonic malignancy: Axial (a and b) and coronal (c) contrast-enhanced computed tomography images in a 73-year-old man presenting with weight loss and worsening left upper quadrant abdominal pain demonstrate a heterogeneous mass arising from the pancreatic tail which is contiguously infiltrating the splenic flexure of colon (arrow in a). There is marked distension of ascending and transverse colon and splenic flexure (asterisk) with decompressed descending colon (arrows in b and c). The large bowel obstruction resulted from contiguous infiltration of the splenic flexure from pancreatic tail cancer.

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis is responsible for approximately 10% of causes for LBO.[1] Several mechanisms are thought to cause an obstruction in patients with diverticulitis including: Adherence of small bowel loops to an inflammatory focus, pericolic fibrosis, a pelvic colon angulated by adhesions, or compression by intramural or extramural abscesses. In MDCT findings of diverticulitis, thickening of the bowel wall is more symmetric, moderate, and extend for a longer segment [Figure 4]. Pericolic changes are important with fat stranding, phlegmon, or intramural or extramural abscesses.[1,11] It can be difficult to distinguish diverticulitis from perforated carcinoma.[11,12] The absence of diverticulum near the lesion, irregularity of the contours, eccentric lumen, ulcerated mucosa, overhanging margins, and an irregular edge favor the diagnosis of a colorectal carcinoma.[9] Some MDCT findings that can be helpful to distinguish diverticulitis from colorectal carcinoma include pericolic inflammation and segmental involvement for diverticulitis.[13] For colorectal carcinoma, MDCT findings may demonstrate pericolic lymph node, a luminal mass, and short segment thickening (<10 cm).[9,14] Patients with a pericolic abscess resulting in LBO are best managed with intravenous antibiotics, bowel rest, percutaneous drainage followed by subsequent resection and primary anastomosis.[8]

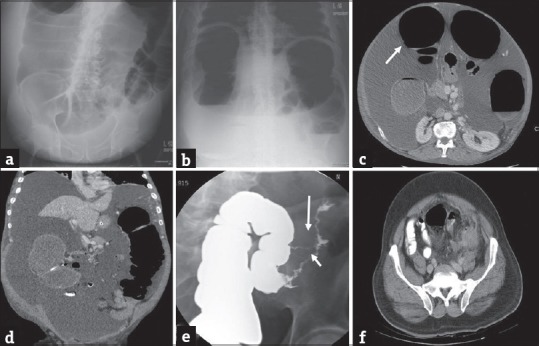

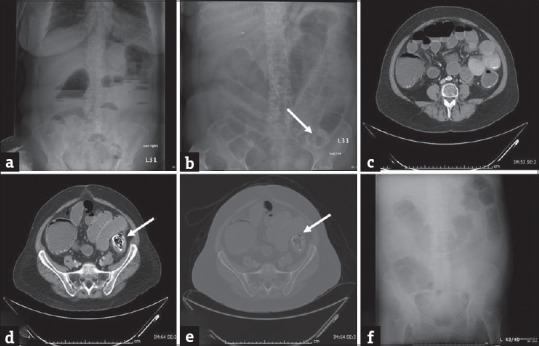

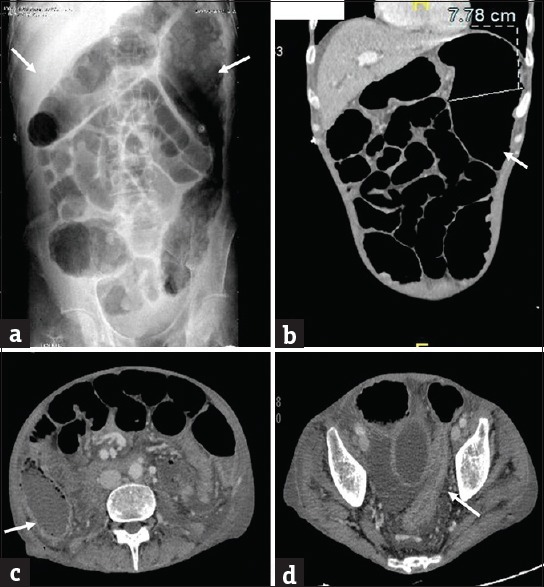

Figure 4.

Large bowel obstruction secondary to diverticular stricture. Plain radiographs of the abdomen, supine and erect views (a and b) in a 45-year-old man presenting to the emergency department with severe abdominal pain and lack of bowel movements demonstrate markedly dilated loops of large bowel compatible with large bowel obstruction. Axial (c) and coronal (d) contrast-enhanced computed tomography images demonstrate dilated large bowel loops (arrow in c) with associated concentric thickening and stricture (arrow in d) of the distal descending colon without discrete mass. Single column barium enema (e) performed subsequently better demonstrates the stricture (short arrow) and an additional fistula (long arrow). Axial computed tomography image (f) performed an year earlier demonstrates changes of acute diverticulitis which eventually led to stricture and large bowel obstruction.

Volvulus

Volvulus is responsible for approximately 10%–15% of all causes of LBO.[14,15] A colonic volvulus must have a segment of redundant mobile colon and a relatively fixed point around which the volvulus can occur. Therefore, the sigmoid colon (70%), cecum (25%), and transverse colon (5%) are the most common sites of volvulus.[1]

Sigmoid volvulus

The sigmoid colon is the most common site of colonic volvulus accounting for nearly 60%–75% of all cases of colonic volvulus.[14] Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, a redundant sigmoid colon with a narrow mesenteric attachment appears to be an anatomical predisposition to develop a sigmoid volvulus.[16] Numerous other risk factors exist including old age, chronic neuropsychiatric disorders, laxative abuse, and chronic constipation.[16]

Plain films typically demonstrate mainly left-sided, distended ahaustral inverted “U”-shaped loop with fluid-fluid levels extending toward the diaphragm on erect films. Supine films typically demonstrate the “coffee bean sign.”[1] MDCT findings typically include a whirl pattern, which is caused by dilated and twisted sigmoid colon around its mesocolon and vessels, and a bird-beak appearance of the narrowed afferent and efferent colonic segments [Figure 5].[17] MDCT offers the advantage of being able to exclude other causes of intestinal obstruction and diagnose complications including perforation.[16,18]

Figure 5.

Sigmoid volvulus: (a) Erect plain abdominal radiograph in a 58-year-old man presenting with abdominal distension and severe lower abdominal pain demonstrates marked distension of the sigmoid colon with a typical coffee-bean sign (arrows) which is highly characteristic of sigmoid volvulus. A rubber tube has been placed for decompression. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography images (b and c) in another patient with similar presentation demonstrates the whirl pattern (arrow in b) and the characteristic bird beak appearance (arrow in c). The redundant and dilated sigmoid colon (asterisk) is better depicted on the coronal image (d) with characteristic beak appearance (arrow).

Delay in diagnosis and treatment can result in a mortality of up to 60% from complications including ischemia, infarction, peritonitis, and sepsis. In most cases, decompression can be performed by insertion of a rectal tube or performing flexible sigmoidoscopy.[16] Flexible sigmoidoscopic decompression is successful in detorsing approximately 85%-95% of patients with sigmoid volvulus; however, it is contraindicated in patients with peritonitis or acute abdomen.[2] Recurrence after decompression can occur up to 90% of cases and can carry a significant mortality.[19] Treatments aimed at preventing recurrence include endoscopic decompression of the volvulus followed by either resection or sigmoidopexy.[16]

Cecal volvulus

Cecal volvulus accounts for 1% of all adult intestinal obstructions and nearly 25%–30% of all cases of colonic volvulus.[20] It is characterized by an acute bowel obstruction from torsion or hyperflexion of an enlarged, poorly fixed, and hypermobile cecum. Cecal volvulus incidence peaks in ages 20–40 years with a slight male predominance; however, all ages may be affected. There are three types of pathophysiological mechanisms which account for cecal volvulus including: Torsion (Type I), loop (Type II), and cecal bascule (Type III).[17] Torsion (Type I) is the axial twisting of the cecum rotating along its long axis and accounts for 90% of all cecal volvulus. Loop (Type II) cecum both twists and inverts. In cecal bascule (Type III), the cecum folds anteriorly without any torsion.[17,20]

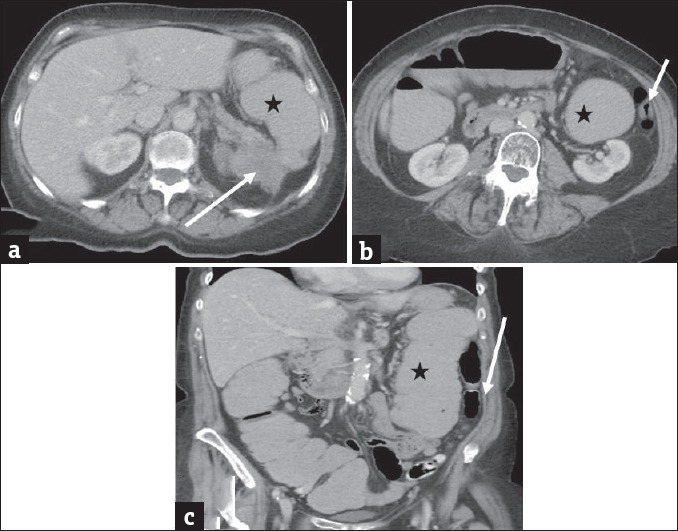

Plain film findings of cecal volvulus, demonstrate a distended cecum that is typically positioned in the left upper quadrant. However, in Type I torsion cecal volvulus, the cecum can twist in the axial plane and appear in the right lower quadrant.[1] MDCT findings demonstrate signs of cecal obstruction and distention [Figure 6]. The transition point can be identified with afferent and efferent loops collapsed. In addition, torsion of the mesenteric vessels can result in the “barber-pole” sign: SMA branches in rotation around the SMV.[21] The only effective treatment for cecal volvulus is surgery.[17]

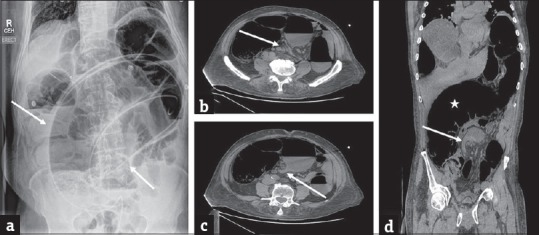

Figure 6.

Cecal volvulus: (a) Erect plain radiograph of the abdomen in a 65-year-old male patient presenting with severe abdominal pain demonstrates mildly dilated loops of small bowel (short arrows) in the right hemi abdomen and a markedly dilated gas filled structure in the left upper quadrant (long arrow) which is compressing the stomach which contains nasogastric tube. Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography images (b and c) demonstrate a large air and fluid filled structure in the left abdomen (asterisk) with absence of cecum in its normal location. A small amount of fluid (arrow) is noted secondary to early ischemia. The enteric contrast is noted to opacify only the small bowel. Imaging findings are concerning for cecal volvulus which was subsequently confirmed at surgery.

Intussusceptions

Adult intussusception is relatively rare with only 5% of all intussusceptions occurring in adults and responsible for 1% of all LBO.[14] In comparison to pediatric intussusceptions (whose etiology is unclear majority of the time), nearly 90% of adult intussusceptions have an organic cause, with 60% being due to neoplasms.[22] In contrast to ileo-ileal intussusception, adult colocolic intussusception is caused by a primary carcinoma in majority of cases.[1] Therefore, resection is usually the best treatment due to high risk of malignancy.[22]

There are several different classic appearances of intussusception on MDCT including: Target appearance (intraluminal soft tissue mass and eccentric fat density), reniform pattern (a bilobed density with peripheral high density attenuation and low attenuation centrally), and Sausage pattern (alternating areas of high and low attenuation related to the bowel wall, mesenteric fat and fluid, intraluminal fluid, contrast, or air).[14,15] MDCT imaging can also help in characterizing the leading mass by its density: Fat-containing lipoma, cystic mass from a mucocele, or a solid tumor [Figure 7].

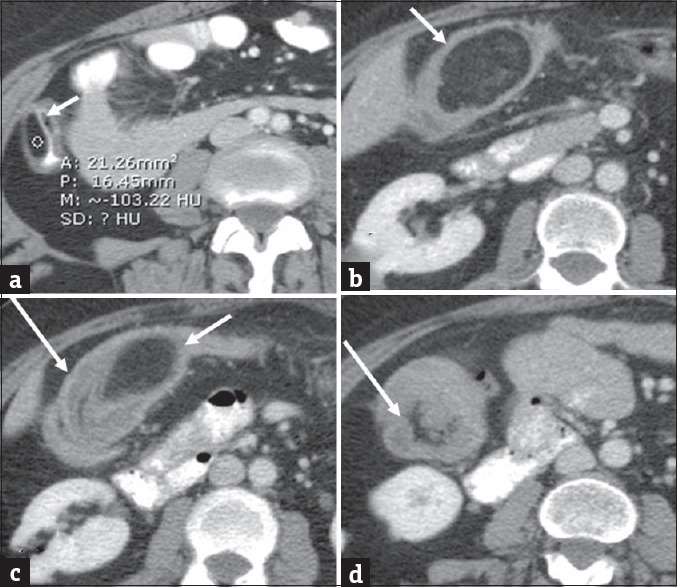

Figure 7.

Colonic lipoma complicated by intussusception. Colonic lipoma complicated by intussusception. Axial (a) contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a 40-year-old man demonstrates small colonic lipoma (arrow). Follow-up computed tomography 5 years later when the patient presented clinically with symptoms of abdominal pain and subacute intestinal obstruction. Axial (b-d) contrast-enhanced computed tomography images demonstrate interval significant growth of the lipoma (short arrows) with associated colonic intussusception (long arrows).

Enterolith

An enterolith is a mineral concentration or calculus usually formed inside a diverticulum, but can be formed anywhere in the gastrointestinal system.[23] Stasis of the intestinal contents is the underlying cause for stone formation.[24] Enteroliths have been found in association with Crohn's disease, tuberculosis, blind loop syndrome, congenital or acquired diverticulum of the small bowel, and intestinal stricture. Enteroliths may also be further divided into false (inspissated intestinal contents) and true. There are many different chemical compositions of enteroliths including: Struvite, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, choleric acid, deoxycholic acid, and cholic acid [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Enterolith: (a and b) Erect and supine plain abdominal radiograph in a 56-year-old man presenting with abdominal distension, vomiting, and severe lower abdominal pain demonstrates dilatation of the small and large bowel loops with associated air-fluid levels concerning for obstruction. A lamellated calcific shadow (arrow) is noted in the left lower quadrant. Computed tomography scan (c-e) performed subsequently confirms an enterolith (arrows) in the distal descending colon which resulted in bowel obstruction. No mass was identified and the patient was managed conservatively with endoscopic fragmentation and removal of the enterolith. Plain abdominal radiograph performed subsequently demonstrated complete removal of the enterolith and interval improvement of bowel obstruction (f).

Fecal Impaction

Fecal impaction is the inability to pass a hard collection of stool and can sometimes result in a LBO. It is a common gastrointestinal disorder, with significant morbidity in all age groups. Having a fiber-depleted Western diet has been found to be a major factor predisposing to constipation and its sequelae including fecal impaction.[25] Physically and mentally incapacitated persons and institutionalized elderly patients are at increased risk. It has been found that fecal impaction appears to increase with age. One study found that 42% of patients in a geriatric ward suffered from fecal impaction.[26] Fecaloma should be considered when there is the focal fecal material of a diameter equal or greater than the colon on MDCT [Figure 9]. Traditional treatment of fecal impaction includes digital manipulation, enema instillation, or disimpaction under anesthesia. Gastrografin enemas can be performed to disimpact the fecal bolus. Fluoroscopic disimpaction should only be performed if there is no evidence of bowel perforation or obstructing colonic lesion on MDCT.[25] Colonic ulceration and perforations can occur after fecal impaction and are secondary to ischemic pressure necrosis caused by a stercoraceous mass.[27] Laparotomy may be required to treat complications of fecal impaction including complete intestinal obstruction or stercoral perforation.[19]

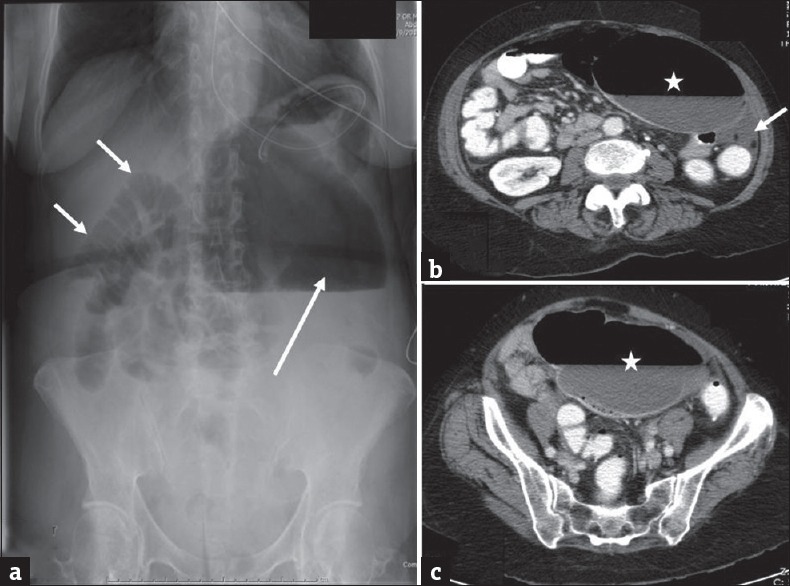

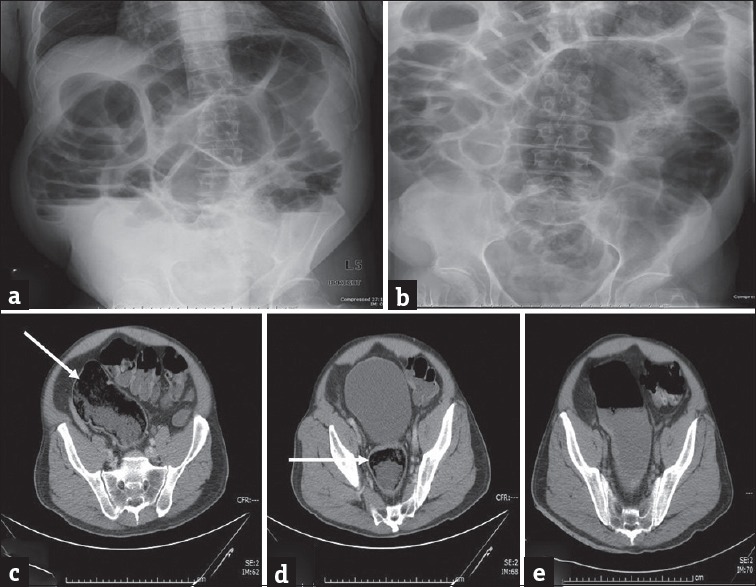

Figure 9.

Fecal impaction: (a and b) Erect and supine plain abdominal radiograph in a 75-year-old man presenting with abdominal distension and worsening lower abdominal pain demonstrates dilatation of the large bowel loops. Computed tomography scan (c and d) performed subsequently demonstrates large amount of stool in the sigmoid colon and rectum (arrows) which resulted in large bowel dilatation. No mass was identified and the patient was managed conservatively with enemas. Repeat computed tomography performed subsequently demonstrates resolution of the impacted feces with residual fluid in the sigmoid colon (e).

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

LBO can rarely be caused by inflammatory bowel disease, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, or tuberculosis. Ulcerative colitis is more common to affect the colon than Crohn's disease; however, it is still rare for either disease to cause a colonic obstruction.[14] Inflammatory bowel disease can give rise to LBO with the development of fibrosis or carcinoma. Fibrosis is more typical of Crohn's disease because of the inflammation is transmural, whereas carcinoma tends to be more typical of ulcerative colitis.[19] The most frequent MDCT findings in both diseases are wall thickening and enhancement. Crohn's disease typically has greater mean wall thickness (11–13 mm) in comparison to ulcerative colitis (7.8 mm).[4]

Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction

Colonic dilatation without mechanical obstruction is called pseudo-obstruction and has been broadly separated into acute and chronic types, with each type having their own disease progression and management. Although there is no obstructing lesion, particularly acute colonic dilatation can be rapidly progressive leading to ischemia and perforation of the large bowel. Added to that, mistaking pseudo-obstruction for mechanical obstruction can lead to unnecessary surgery. The acute type is usually known as Ogilvie's syndrome.[15,19] The exact pathogenesis of Ogilvie's is unknown, however an imbalance in autonomic nervous system activity is thought be a major contributing factor. In a review of cases, Ogilvie's most prominent symptoms are an abdominal pain (83%), constipation (51%), diarrhea (41%), fever (37%), and abdominal distention.[28] It most often occurs in patients who are critically ill, have electrolyte imbalances, or are on anticholinergic medications. If untreated, life-threatening complications such as bowel ischemia or perforation can occur in up to 15% of cases with 50% mortality.[28,29]

Abdominal radiograph show nonspecific diffuse colonic dilatation. MDCT is the definitive modality and show extensive proximal colonic dilatation with an intermediate transitional zone at or adjacent to the splenic flexure and without any structural obstructing lesions [Figure 10]. Cecal ischemia and perforation are the major complications and cecal diameter >12 cm and prolonged distension for more than 2–3 days is an indication for intervention.[29] Close differential is paralytic ileus due to recent surgery, peritonitis, or electrolyte imbalance. In contrast to Ogilvie's syndrome, usually there is no transition point near splenic flexure, minimal luminal fluid, often associated SBO and clinically more stable patient in colonic adynamic ileus [Figure 11].

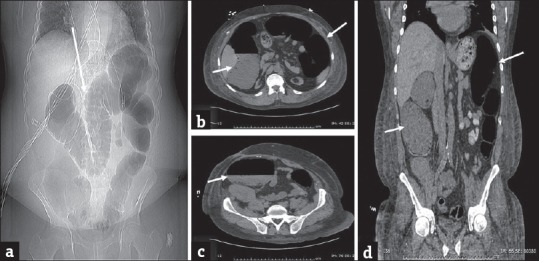

Figure 10.

Ogilvie's syndrome: (a) Plain abdominal radiograph in a 61-year-old man presenting with abdominal distension demonstrates marked distension of the colon (arrow). Computed tomography scan (b-d) performed subsequently reveal distended colon (arrows). There is no evidence of small bowel dilatation or obstructing lesion. The patient was managed conservatively.

Figure 11.

Adynamic ileus in a 65-year-old man with diabetes presenting with diffuse intermittent abdominal pain and found to have sever hypokalemia. (a) Plain abdominal radiograph shows diffuse dilatation of colon. Axial (b-d) contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows diffuse dilatation of both small bowel (long arrows) and colon (short arrows) all the way to rectum without transition.

Generally, management for Ogilvie's is conservative including bowel rest, intravenous fluids, gentle enemas, regular clinical, and radiologic assessment.[19] Neostigmine is an acetyl cholinesterase inhibitor which acts in a reversible manner. It stimulates muscarinic receptors which increase motor activity of colon and results in the propulsion of feces within the colon. Patients that fail to respond to neostigmine may require further therapeutic options such as colonoscopic decompression, elective cecostomy, and decompressive blow-hole colostomy. Complications such as peritoneal irritation or free air require urgent laparotomy, with mortality of perforation ranging from 46% to 75%.[19,29]

Toxic Megacolon

Toxic megacolon is a rare but severe and potentially fatal complication of colonic inflammation. It is most commonly considered a complication of inflammatory bowel disease, specifically ulcerative colitis, but occasionally Crohn's disease. The list of etiological factors have been expanded to include a large number of infectious conditions including colitis form infectious organisms such as Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Cytomegalovirus, and Entamoeba. The exact pathophysiology is not completely understood. However, there is an established association of inflammatory conditions of the colon and decreased smooth muscle contractility.[30]

The consistent feature of toxic megacolon is the radiographic evidence of total or segmental colonic distention of >6 cm. In comparison to other etiologies of colonic dilatation (Ogilvie's syndrome, Hirschsprung's disease), toxic megacolon is defined by the additional presence of systemic toxicity and inflammatory or infectious etiology of the underlying disease.[31] The most commonly used clinical criteria for the diagnosis of toxic megacolon include three of the four following main criteria: Fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, or anemia. In addition, one of the following criteria should also be met: Dehydration, altered level of consciousness, electrolyte imbalance, or hypotension.[32]

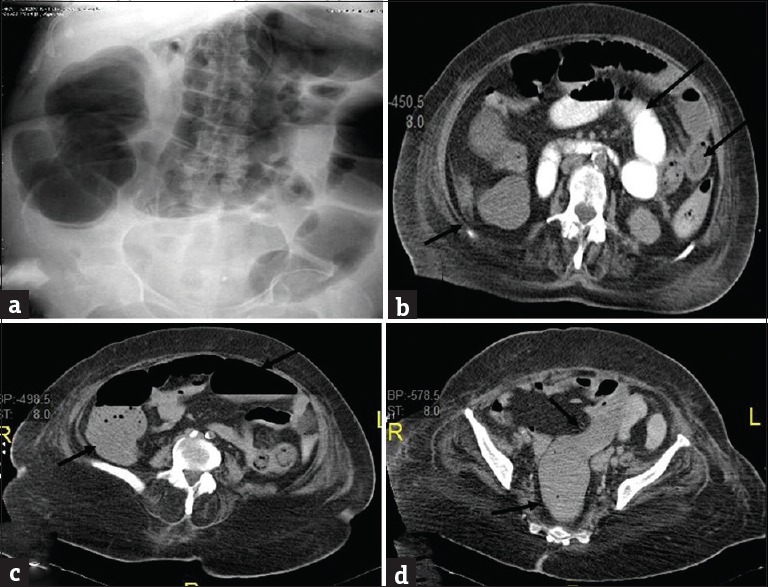

Typical features seen on plain film include ahaustral dilatation of the colon >6 cm ranging up to 15 cm. The mean documented diameter is 9.2 cm.[30] MDCT scans can help identify severe colitis that can predispose to toxic megacolon. These findings include diffuse colonic wall thickening, thickened haustra with alternating bands of high and low density (“accordion sign”), multilayered appearance caused by different densities of edematous submucosa, hyperemic mucosa (“target sign”), and pericolic stranding. In addition, detecting colonic dilatation (>6 cm) is indicative of developing toxic megacolon [Figure 12].[30]

Figure 12.

Toxic megacolon in a 55 year old man with known ulcerative colitis. (a) Plain abdominal radiograph shows dilatation of transverse colon and splenic flexure with loss of haustrations. Coronal (b) CT images show the dilatation of splenic flexure with loss of haustrations (arrows). Axial (c and d) CT images demonstrate the changes of acute colitis in the cecum (arrow in c) and rectosigmoid (arrow in d).

The main-stay of medical therapy in patients with toxic megacolon secondary to ulcerative colitis is high-dose intravenous steroids. First-line surgical procedure in acute toxic megacolon is subtotal colectomy with an ileostomy and either a Hartmann's pouch or sigmoidostomy or rectostomy.[33] Currently, the timing of surgery in toxic megacolon remains controversial. Circumventing the necessity of surgery is the goal for all medical treatments; however, delaying surgical therapy can increase the risk of complications such as bowel perforation or abdominal compartment syndrome leading to a poor prognosis.[30]

Stricture

Rectosigmoid stricture can be a complication of vascular compromise, malignancy, radiation, inflammation, or infection. Ischemic colitis generally involves the watershed areas at the splenic flexure and rectosigmoid junction, because it has the most vulnerable collateral blood flow.[34] Radiation colitis is a form of ischemic colitis, with the stricture usually being responsible for the obstruction. The sigmoid colon and rectum are affected most frequently because radiation is often used for pelvic disease [Figure 13].[1]

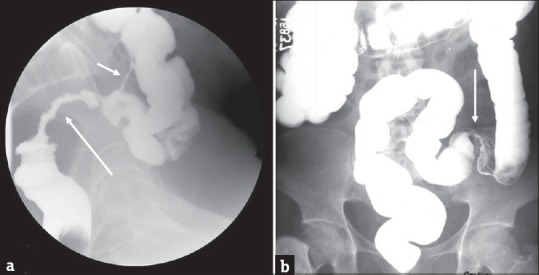

Figure 13.

Stricture: (a) Single column barium enema in a 59-year-old man who underwent pelvic irradiation demonstrates a long segment irregular stricture of the rectosigmoid (long arrow). Also noted is a colocolic fistula (short arrow) which is another potential complication of radiation therapy. Barium enema in another patient with history of ischemic colitis demonstrates a short segment smooth stricture (arrow) at the junction of the sigmoid and descending colon (b).

Conclusion

LBO is a common clinical entity in which imaging plays a key role in the identification of etiology, site of obstruction, and early detection of complications. Knowledge of the conditions causing LBO and their imaging features can help the emergency radiologist to promptly triage the patients, thereby facilitating prompt and appropriate management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2017/7/1/15/203884

References

- 1.Taourel P, Kessler N, Lesnik A, Pujol J, Morcos L, Bruel JM. Helical CT of large bowel obstruction. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:267–75. doi: 10.1007/s00261-002-0038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo HL, Lee SW. Colorectal emergencies: Review and controversies in the management of large bowel obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:2007–12. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore RM, Levine MS, editors. Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton KM, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT evaluation of the colon: Inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2000;20:399–418. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc15399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frager D, Rovno HD, Baer JW, Bashist B, Friedman M. Prospective evaluation of colonic obstruction with computed tomography. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:141–6. doi: 10.1007/s002619900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godfrey EM, Addley HC, Shaw AS. The use of computed tomography in the detection and characterisation of large bowel obstruction. N Z Med J. 2009;122:57–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman AH, McNamara M, Porter G. The acute contrast enema in suspected large bowel obstruction: Value and technique. Clin Radiol. 1992;46:273–8. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frago R, Ramirez E, Millan M, Kreisler E, del Valle E, Biondo S. Current management of acute malignant large bowel obstruction: A systematic review. Am J Surg. 2014;207:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayakawa K, Tanikake M, Yoshida S, Urata Y, Yamamoto E, Morimoto T. Radiological diagnosis of large-bowel obstruction: Neoplastic etiology. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izuishi K, Sano T, Okamoto Y, Mori H, Oryu M, Maeta T, et al. Large-bowel obstruction caused by pancreatic tail cancer. Endoscopy. 2012;44(Suppl 2 UCTN):E368–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chintapalli KN, Chopra S, Ghiatas AA, Esola CC, Fields SF, Dodd GD., 3rd Diverticulitis versus colon cancer: Differentiation with helical CT findings. Radiology. 1999;210:429–35. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.2.r99fe48429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balthazar EJ. CT of the gastrointestinal tract: Principles and interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:23–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.1.1898566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmi A, Hedgire SS, Pargaonkar V, Cao K, McDermott S, Harisinghani M. Is early colonoscopy beneficial in patients with CT-diagnosed diverticulitis? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:1269–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayakawa K, Tanikake M, Yoshida S, Urata Y, Inada Y, Narumi Y, et al. Radiological diagnosis of large-bowel obstruction: Nonneoplastic etiology. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30:541–52. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe T, Thompson WM. Large-bowel obstruction in the adult: Classic radiographic and CT findings, etiology, and mimics. Radiology. 2015;275:651–63. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015140916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wai CT, Lau G, Khor CJ. Clinics in diagnostic imaging (105): Sigmoid volvulus causing intestinal obstruction, with successful endoscopic decompression. Singapore Med J. 2005;46:483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delabrousse E, Sarliève P, Sailley N, Aubry S, Kastler BA. Cecal volvulus: CT findings and correlation with pathophysiology. Emerg Radiol. 2007;14:411–5. doi: 10.1007/s10140-007-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levsky JM, Den EI, DuBrow RA, Wolf EL, Rozenblit AM. CT findings of sigmoid volvulus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:136–43. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Kostner F, Hool GR, Lavery IC. Management and causes of acute large-bowel obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:1265–90. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habre J, Sautot-Vial N, Marcotte C, Benchimol D. Caecal volvulus. Am J Surg. 2008;196:e48–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepage-Saucier M, Tang A, Billiard JS, Murphy-Lavallée J, Lepanto L. Small and large bowel volvulus: Clues to early recognition and complications. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouaqit O, Hasnai H, Chbani L, Oussaden A, Maazaz K, Amarti A, et al. Pedunculated lipoma causing colo-colonic intussusception: A rare case report. BMC Surg. 2013;13:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quazi MR, Mukhopadhyay M, Mallick NR, Khan D, Biswas N, Mondal MR. Enterolith containing uric acid: An unusual cause of intestinal obstruction. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:295–7. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0262-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Tinay Oel-F, Guraya SY, Noreldin O. Enterolithiasis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:96–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar P, Pearce O, Higginson A. Imaging manifestations of faecal impaction and stercoral perforation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read NW, Abouzekry L, Read MG, Howell P, Ottewell D, Donnelly TC. Anorectal function in elderly patients with fecal impaction. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:959–66. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narayanaswamy S, Walsh M. Calcified fecolith – A rare cause of large bowel obstruction. Emerg Radiol. 2007;13:199–200. doi: 10.1007/s10140-006-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie's syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:203–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02555027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel JD, Feingold DL, Stewart DB, Turner JS, Boutros M, Chun J, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Colon Volvulus and Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:589–600. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Autenrieth DM, Baumgart DC. Toxic megacolon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:584–91. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheth SG, LaMont JT. Toxic megacolon. Lancet. 1998;351:509–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jalan KN, Sircus W, Card WI, Falconer CW, Bruce CB, Crean GP, et al. An experience of ulcerative colitis. I. Toxic dilation in 55 cases. Gastroenterology. 1969;57:68–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ausch C, Madoff RD, Gnant M, Rosen HR, Garcia-Aguilar J, Hölbling N, et al. Aetiology and surgical management of toxic megacolon. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bobba RK, Arsura EL, Amir KA. Rectosigmoid stricture probably from ischemia presenting as constipation in an elderly patient. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1634–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53487_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]