Abstract

Research has demonstrated that youth who age out, or emancipate, from foster care face deleterious outcomes across a variety of domains in early adulthood. This article builds on this knowledge base by investigating the role of adverse childhood experience accumulation and composition on these outcomes. A latent class analysis was performed to identify three subgroups: Complex Adversity, Environmental Adversity, and Lower Adversity. Differences are found amongst the classes in terms of young adult outcomes in terms of socio-economic outcomes, psychosocial problems, and criminal behaviors. The results indicate that not only does the accumulation of adversity matter, but so does the composition of the adversity. These results have implications for policymakers, the numerous service providers and systems that interact with foster youth, and for future research.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), foster care, aging out, emancipation, young adulthood, latent class analysis, socio-economic outcomes, psychosocial problems

1. Introduction

1.1. Childhood Adversities and Foster Youth

The rate of youth emancipate or “age out” of foster care each year is large and increasing. Specifically, between 2008 and 2013 the proportion of youth in foster care who aged out of the system rather than being adopted or entering a guardianship increased from six to ten percent of all exits, totaling between 23,000 and more than 29,000 youth a year (U.S Children’s Bureau, 2009, 2014). These youth are frequently exposed to significant early adversity experiences and, perhaps resultant from these experiences, struggle in a number of domains during the transition to adulthood. Former foster youth particularly struggle with homelessness and housing stability (Dworsky, Napolitano, & Courtney, 2013; Fowler, Toro, & Miles, 2009; Reilly, 2003), education completion (Blome 1997; Courtney, Dworsky, Brown, Cary, Love, & Vorhies, 2011), employment and financial stability (Goerge et al., 2002; Needell, Cuccaro-Alamin, Brookhart, Jackman, & Shlonsky, 2002), and mental health concerns (Pecora, White, Jackson, & Wiggins, 2009) during this period in the life course.

Further, many foster youth who emancipate or age out of foster care do not receive the social support that is typical of their general population peers. For example, Settersten and Ray (2010) find that parents are currently supporting their young adult children more than any other time in recent history. Many youth aging out of foster care not only contend with the effects of their childhood adversity histories, but also with the additional stress that a lack of social and financial support from families affords. The combination of early adversity histories and underdeveloped support networks leave some youth in foster care particularly susceptible to poor outcomes in young adulthood.

Studies on the heterogeneity of youth who age out of foster care have been conducted, primarily focused on their adult functioning. Keller, Cusick, and Courtney (2007) used latent class analysis to identify specific subgroups of youth about to age out of foster care in regards to their readiness for independent living. Four classes were identified: Distressed and Disconnected, Competent and Connected, Struggling But Staying, and Hindered and Homebound. A different study looked at how youth were doing in young adulthood, specifically ages 23 and 24 and in regards to their adult functioning (Courtney, Hook, & Lee, 2012). This study also found four classes: Accelerated Adults, Struggling Parents, Emerging Adults, and Troubled and Troubling. These studies highlight that aging out youth experience different trajectories of functioning as they enter young adulthood. Thus, more research is needed to understand what types of stress exposures lead to these diverse trajectories, to inform efforts to improve outcomes for all youth who emancipate from care.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) research demonstrates that greater number of early life exposures to significant stressors (e.g, maltreatment, household adversities such as substance abuse, mental illness, intimate partner violence, and criminal behaviors) are significantly associated with greater mental and physical health problems in the adolescent and adult age periods (Anda et al., 2006; McLaughlin et al., 2010). This research suggests that early life adversities are not only interrelated, but also that they function in a cumulative manner. Although details regarding onset, frequency, and duration of experiences are often assessed within clinical samples research, ACEs assessment has typically consisted of epidemiologic dichotomous assessment of types of adversity exposures suited to population-based sampling estimates (Anda, Butchart, Felitti, & Brown, 2010). Cumulative adversity assessed in this way has been linked with changes to various aspects of the developing brain, maladaptive health and behavioral habits, and difficulties in developing healthy relationships (Shonkoff et al., 2012 provides a summary).

Prevalence of ACEs in the general population has been estimated in prior research. For the original large HMO-based study of the traditional ACES in adults, 49.5% of participants reported experiencing zero categories of ACEs, 24.9% experienced one ACE, 12.5% reported two ACEs, while 6.9% experienced three and 6.2% reported four or more categories of ACEs (Felitti et al., 1998). Similar results were found in another study using a sample of noninstitutionalized adults from five states, the authors found 40.6% reported no ACE categories, 22.4% reported one ACE category, two categories were reported by 13.1%, 8.8% reported three categories, 6.5% reported four, and 8.7% reported five or more ACEs (Ford, et al., 2011).

Recent ACEs research expands upon the original set of childhood adversities used in assessing a predominantly white, educated sample (Felitti et al., 1998) to incorporate other experiences to which lower income and racial minority are differentially exposed. Specifically, qualitative methods have been used to identify environmentally based adversities among socially disadvantaged groups (Wade, Shea, Rubin, & Wood, 2014). Examples include hazards such as fires, accidents, witnessing violence or being victimized outside the home, and foster care settings (Cronholm et al., 2015; Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2013). Parallel research has examined aspects of youth’s social environments and residential instability as adversities that demonstrate impact on subsequent youth outcomes (Douglas et al., 2010; Wickrama & Noh, 2010).

These studies suggest that the relationship between stress exposure and adolescent/adult outcomes may be particularly impactful for youth who live within socially disadvantaged contexts and that expanded ACEs that capture environmental adversities is warranted. Initial results demonstrate gender (male), race (respondents of color) and poverty to be significantly associated with greater environmental adversity exposure (Cronholm et al., 2015). Thus, sociodemographic and other characteristics can differentially place youth in environments that carry additional risks, such as community violence or hazards. Further, there are indications that the structural factors of poverty and racism may increase the risk of experiencing ACEs (Kalmakis & Chandler, 2014). Given the sociodemographic diversity of foster care youth, assessment of both cumulative level and composition differences relative to types of adverse childhood experiences may be relevant.

The effects of early life adversity on later development and health have been established to function through multiple pathways across the life course. This includes biological mechanisms through which adversity exposures cause strain, dysregulations, maladaptive stress response habits, and poorer physical and mental health (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011 provide a summary). It also includes psychosocial pathways through which secondary stressors (e.g., doing poorly in school settings) contribute to a pattern of subsequent stress exposures (e.g., school failure, low income, psychosocial difficulties, involvement in higher risk activities) that progressively leads to poor health and functioning outcomes (Baglivio et al., 2014; Boynton-Jarrett, Hair, & Zuckerman, B., Pearlin, 2010). As chronic stress accumulates and persists, self-regulation processes are overwhelmed, preventing youth from effectively coping with their life stressors, curtailing their future abilities to manage stress and to acquire protective resources toward reducing and buffering adversities (Evans & Kim, 2012).

The ecobiodevelopmental framework integrates these pathways from cumulative stress to poorer outcomes, noting that, “beginning prenatally, continuing through infancy, and extending into childhood and beyond, development is driven by an ongoing, inextricable interaction between biology (as defined by genetic predispositions) and ecology (as defined by the social and physical environment)” (Shonkoff et al. 2012, p. 234). This framework is particularly applicable to foster youth who have often spent at least part of their childhoods in environments or ecologies marked with stress and trauma, and has been recommended for use in support systems for vulnerable children and families such as foster care (Garner et al., 2012). Within this framework, the childhood adversities these youth endure become manifest, altering their biological and psychosocial development, which, in turn, biases the kind of future contexts and challenges with transitions they are likely to encounter.

1.2. The Present Study

Although emancipating foster youth approach the onset of adulthood with high rates of exposure to traumatic events and stressors (Courtney et al. 2001; Salazar, Keller, Gowen, & Courtney, 2013), little is known about the compositional variations of maltreatment and related adversity profiles, or implications of variations for youths’ later health and functioning. Stress paradigms have been productive in linking cumulative adversity approaches to health and development outcomes in general populations, and hold promise for application to high-risk youth populations (Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Clearer characterization of the adversity histories that emancipating youth bring to their transition into adulthood will inform policy and practice to best serve the needs of these youth, with the hopes of disrupting trajectories of continued stress exposure in adulthood and maladaptation.

At this relatively early stage of ACEs research focused on emancipating youth in foster care, we also need a fuller understanding of the heterogeneity within this population. For that, person-centered tools, such as Latent Class Analysis (LCA), provide complementary analytic approaches to variable oriented approaches. Variable oriented analysis (such multiple regression) are useful in characterizing aggregate trends across full samples and provide a strong foundation for subsequent investigations testing for variation—in this case differences in the nature of adverse experiences that may indicate differences in developmental contexts of foster care youth. Person-oriented tools support assessment of meaningful multivariate patterns among people on the basis of conceptually specified measures, such as violence and related adversity exposure (Logan-Greene, Kim, & Nurius, 2016; Nurius & Macy, 2008). These patterns distinguish one group from another, results that can potentially aid in subsequent investigation such as suggesting potential intervention strategies or assessing the effects of such interventions (Cooper & Lanza, 2014).

One innovative example has been the work of Havlicek (2014) applying a latent class analysis to explore the maltreatment histories of a cohort of Illinois youth who had aged out of foster care using administrative data. Four classes were identified as chronic maltreatment (five or more types of maltreatment occurring over at least three developmental periods), predominant abuse (higher levels of physical and sexual abuse), situational maltreatment (most likely to have experienced maltreatment during one developmental period), and predominant neglect (experienced neglect almost exclusively). The heterogeneity of maltreatment histories found by Havlicek support our theorizing that clinically meaningful profiles of adverse experience histories will be evident in the current study. In the present study, we aimed to extend Havlicek’s findings through a broader array of adversities likely to affect youth development and health, using a larger, multi-state longitudinal sample of youth transitioning out of foster care. The use of LCA also allows movement beyond the original conceptualization of adverse childhood experiences as an additive model, testing to see if the composition of those adversities are also significant.

Specifically, the purpose of this study was to assess whether different profiles among foster care youth are evident based on childhood adversity exposures. In addition to level differences (greater versus lesser types of adversity exposure), we aimed to determine if compositional differences distinguish emancipating youth. That is, that in addition to cumulative adversity, we sought to determine whether there was clustering of adversity experiences, and whether these are associated with sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, we assessed the extent to which youth with distinct adversity profiles differed with respect to subsequent socio-economic, psychosocial, and criminal behavior outcomes that are consequential to successful transition into young adulthood and that may provide insights as to stress proliferation (e.g., poorer subsequent education and socioeconomic conditions) as well as more evidence of psychosocial problems and criminological risk behaviors and outcomes that would contribute to poorer health and functioning future outcomes. Data on health risk behaviors and outcomes will presented in a separate paper.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Procedure

The sample used for this study was from the Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth (Midwest Study), the largest longitudinal study of youth aging out of foster care (Courtney et al., 2011). Youth were considered eligible for the study if in May 2002 they were being supervised by the public child welfare agency in out-of-home care in three Midwestern States (Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin); were between the ages of 17 and 17 ½ years old; and prior to their 17th birthdays, had been in care for at least one year (Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004). Youth were excluded from the sample if they were unable to participate due to a developmental disability, severe mental illness, hospitalization or incarceration at the time, were in an out-of-state placement, or their whereabouts were unknown (runaway status) throughout the study field period. All eligible youth from Iowa and Wisconsin and two-thirds of the eligible youth from Illinois who fit the study criteria were included in the study. In wave one, the study had a response rate of 95.4 % based on the 767 youth who were determined to be eligible and were approached; 732 youth consented and completed a baseline interview (63 youth from Iowa, 195 from Wisconsin, and 474 from Illinois). Four subsequent waves of data have been collected when youth were 19 years old, 21 years old, 23–24, and 25–26 years old, respectively; retention rates ranged between 81–83% for all follow up waves.

2.2. Sample

Demographically, the sample included 354 males (48.4%) and 378 females (51.6%). Over half (55.88%) of the sample identify as Non-Hispanic Black, 29.05% as Non-Hispanic White, 8.02% as Any Race Hispanic, 5.12% as Mixed Race, and 1.94% as Other Race. No statistically significant demographic differences were found between the full sample and the Wave 5 sample, indicating stability of racial representation in the sample over time.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences

Consistent with recent investigations (e.g., Greeson et al., 2014; Wade et al., 2014), our aim was to conduct an expanded ACEs assessment, that included maltreatment variables as well as other adversity experiences highly salient to this vulnerable population—in this case, stressors associated with the foster care system and experiences in the youth’s social environment. Therefore, fifteen self-report dichotomous childhood stressor variables collected in Wave 1 (age 17) are included from three dimensions of adversity. All are assessed in dichotomous form (yes/no).

Maltreatment

Four factors were assessed. Sexual abuse was based on a yes response to having experienced rape, sexual assault, or sexual molestation at any time prior to the baseline interview in which the relationship of the perpetrator was not specified. Physical abuse was based on experiencing at least one of the following: being thrown/pushed, locked in a room or closet, punched/slapped/kicked, beat up, choked/strangled, attacked with a weapon, or tied up/held down/blindfolded prior to entering foster care. Neglect was assessed on experiencing at least one of eight items prior to entering foster care: neglect related to food, grooming, medical care, misappropriation of money, chores, caregiver illness, missing school, and insufficient protection. Abandonment prior to entering foster care was based on a single item. The latter three factors were derived from the Lifetime Experiences Questionnaire (Rose, Abramson, & Kaupie, 2000) which specified a caregiver as the perpetrator. It is worth noting that all of the maltreatment experiences reported here, with the exception of the items capturing sexual abuse, involve the actions of one or more of the child’s caregivers prior to entry to foster care.

Household factors

Six factors were included. Four factors consistent with the original ACEs framework (Felitti et al., 1998) captured characteristics of the household from which the youth was removed at the time they were placed in foster care: caregiver substance abuse (alcohol or drugs); caregiver had a mental illness; caregiver domestic violence (abused their spouse); and caregiver had a criminal record. In addition, two factors captured youth’s experiences of adversity while in care: youth placement in five or more foster homes, and youth experienced an adoption plan failure.

Environmentally based forms of harm

Five factors of our clustering are included if, at any time prior to the baseline interview, either in foster care or not, the youth had experienced: witnessing others being hurt or killed; physical fighting (either direct combat or a serious physical assault), a natural disaster or fire, a life-threatening accident, or sustaining a very serious injury.

2.3.2. Young Adult Outcomes

Young adult outcome questions were examined from waves two through five (ages 19–26), dichotomously coded yes/no (1, 0) if a youth responded yes in one or more of the four follow-up waves. Outcomes were chosen as indicators of stress proliferation; e.g., elevated likelihood of experiencing greater psychological distress, higher risk activities, and lesser socioeconomic success which serve as secondary stressors to impede transition into successful adulthood (Baglivio et al., 2014; Min, Minnes, Kim, & Singer, 2013). These outcomes have also been found higher among former foster youth compared to youth in the general population and, thus, important markers to address in stress-based analysis (Courtney, Dworsky, Brown, Cary, Love, & Vorhies, 2011; Courtney, Dworsky, Cusick, Havlicek, Perez, & Keller, 2007; Courtney, Dworksy, Lee, & Raap, 2010; Courtney, Dworsky, Ruth, Kelller, Havlicek, & Bost, 2005; Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004). As noted previously, we also evaluated health risk behaviors and outcomes which will be presented in a separate paper.

Socio-economic outcomes

Outcomes included whether the youth completed high school or a GED, had any college experience, reported receiving economic insecurity assistance (food stamps, public housing, or state cash assistance), or experienced homelessness.

Psychosocial outcomes

Mental health indicators included reporting five or more depressive symptoms; having one or more PTSD symptom that lasted at least a month and receiving mental health treatment. Substance abuse indicators included having one or more drug dependence symptoms; having one or more alcohol dependence or abuse symptoms, and receiving substance abuse treatment. These questions are from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, developed as a highly structured interview to be used by non-clinicians (World Health Organization 1998), except for the questions regarding receipt of either treatment.

Criminal Behaviors

Outcomes in this category included whether the youth had ever traded or was paid for sex, or had ever been arrested, convicted of a crime, held gang membership, or sold drugs (dichotomous yes/no). Also included were dichotomous categories based on if the youth answered affirmatively to the following at any of waves 2–5: economic criminal behavior (using someone else’s credit card without permission or purposefully writing a bad check), violent delinquent behavior (using a weapon to get something, participating in a gang fight, using a weapon in a fight, or carrying a handgun to work/school), and property criminal behavior (damaging property, stealing, entering a building to steal, and buying or selling stolen property).

2.4. Analytic Approach

We performed a Latent Class Analysis (LCA) with MPlus v7.4. LCA is a method used to improve the comprehension of complex datasets and the interrelationships between observed variables by identifying membership of a small number of latent classes (Bartholomew, Steele, Moustaki, & Galbraith, 2008). We used the above-described adverse childhood experience variables to test for subgroup structure within ACEs histories among this population of youth aging out of foster care. The objective of LCA is to identify the least number of classes needed to account for the distinctions in clustering between the classes. Model fit indices of various solutions about the number of classes were examined: 1) Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), an index where smaller numbers suggest a better fit after applying a penalty based on the number of parameters (Muthen & Muthen, 2007), 2) Entropy where better separation of the identified classes are indicated by higher values, and 3) Vuong-Lo-Mendell Likelihood Ratio Test and Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR) that test the superiority of a K-class model against a K-1 class model. Chi square tests of independence were then used to test the relationship between the classes relative to race and gender and the young adult outcomes variables.

3. Results

3.1. LCA Class Characteristics

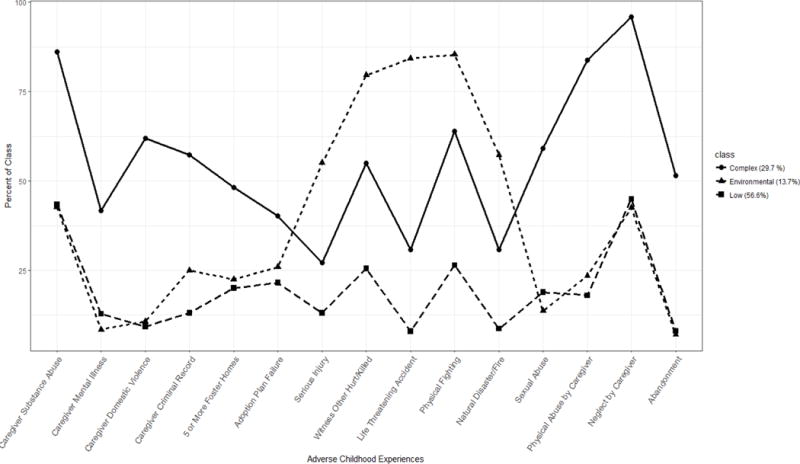

The multiple fit statistics indicated that a three-class model best fit the data. The lower BIC score (12148.24) for the three-class model coupled with the non-significant p-values for the Vuong-Lo-Mendall Likelihood Ratio Test (0.195) and Lo-Mendall-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test (0.198) for the four-class model support the choice of the three-class model. The results of the model-fit statistics are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1. Based on the three-class model, the identified classes labeled are 1) Complex Adversity (N = 214; 29.32%), 2) Environmental Adversity (N = 89; 12.19%), and 3) Lower Adversity (N = 427; 58.49%).

Table 1.

Model-Fit Statistics Comparisons

| Model | BIC | Entropy | Vuong-Lo-Mendell LR Test p-value | Lo-Mendall-Rubin Adjusted LR Test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Class | 12177.75 | 0.734 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 3-Class | 12148.24 | 0.734 | 0.025 | 0.026 |

| 4-Class | 12176.5 | 0.758 | 0.195 | 0.198 |

Figure 1.

Adverse Childhood Experiences by Class

The Complex Adversity class has the highest proportions of youth who had experienced the maltreatment variables and the adverse household factors. For example, 86.14 % of this class experienced caregiver substance abuse, 62.00% experienced caregiver domestic violence, 48.13% lived in five or more foster homes, 95.98% were neglected by their caregiver, and 83.76% were abused by their caregiver. Youth in the Environmental Adversity class are distinctive in their high rate of exposure to harm in their environment. In this class, 79.55% experienced witnessing another seriously hurt or killed, 84.27% experienced a life-threatening accident, and 85.39% had engaged in physical fighting. The Lower Adversity class did not experience any of the variables at a higher rate than the other two classes. In fact, the Lower Adversity class had similar rates of experiencing the caregiver/context factors and maltreatment variables as the Environmental Adversity class, but experienced the harm exposures in the environment at a lower rate than both of the other two classes. Differences in the class proportions responding yes achieve statistical significance for each of the ACE items (see Table 2). Table 2 also reflects differences in the total number of adverse childhood experiences, wherein the Complex Adversity class leads with a mean of 7.92 (median = 8) adversities and a maximum of 14, the Environmental Adversity class with a mean of 5.71, median of 5, and a maximum of 9, and the Lower Adversity class with a mean of 2.85, median of 3, and a maximum of 6. The identified classes did not vary by state.

Table 2.

Percentages of Adverse Childhood Experiences Variables by Class

| Complex (29.32%) | Environmental (12.19%) | Low (58.49%) | X2 | Between Classes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver/context factors | |||||

| Caregiver Sub Abuse | 86.14 | 42.68 | 43.37 | 107.01*** | a, b |

| Caregiver Mental Illness | 41.67 | 8.43 | 12.84 | 74.94*** | a, b |

| Caregiver Domestic Violence | 62.00 | 10.71 | 9.22 | 212.25*** | a, b |

| Caregiver Criminal Record | 57.38 | 25.00 | 13.11 | 123.89*** | a, b, c |

| 5+ Foster Homes | 48.13 | 22.47 | 20.00 | 57.04*** | a, b |

| Adoption Plan Failure | 40.29 | 25.88 | 21.51 | 24.72*** | a, b |

| Environmental based harms | |||||

| Serious Injury | 27.1 | 55.06 | 13.11 | 78.68*** | a, b, c |

| Witness Other Hurt/Killed | 54.93 | 79.55 | 25.53 | 113.66*** | a, b, c |

| Life Threating Accident | 30.84 | 84.27 | 7.96 | 243.13*** | a, b, c |

| Physical Fighting | 63.98 | 85.39 | 26.42 | 148.76*** | a, b, c |

| Natural Disaster/Fire | 30.84 | 57.3 | 8.67 | 121.94*** | a, b, c |

| Maltreatment | |||||

| Sexual Abuse | 59.15 | 13.64 | 18.91 | 121.94*** | a, b |

| Neglect by Caregiver | 95.98 | 42.53 | 45.01 | 155.78*** | a, b |

| Abandonment | 51.53 | 6.98 | 7.99 | 167.22*** | a, b |

| Physical Abuse by Caregiver | 83.76 | 23.53 | 18.00 | 253.91*** | a, b |

|

| |||||

| Mean Number of ACEs | 7.92 | 5.71 | 2.85 | a, b, c | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

a = statistically significant difference between Complex & Environmental classes

b = statistically significant difference between Complex & Lower classes

c = statistically significant difference between Environmental & Lower classes

3.2. Differences in Young Adult Outcomes

Whereas Complex and Lower Adversity youth were roughly balanced by gender, Environmental Adversity youth were more likely to be male (66.29%). Complex Adversity youth were less likely to be black and more likely to be white relative to the other two youth groups. Youth across the classes were largely comparable in terms of educational attainment and receipt of public assistance for economic insecurity, with no significant differences.

Complex Adversity youth were significantly more likely to report homelessness, depressive symptoms, and engagement in property crime behavior than the Lower Adversity youth. Additionally, in comparison to both of the other classes, the Complex Adversity class reported significantly higher rates of mental health treatment. Environmental Adversity youth were distinct in greater prevalence of being arrested compared to both Lower and Complex Adversity youth. Both Complex Adversity and Environmental Adversity youth reported higher rates of PTSD, drug, and alcohol abuse symptoms, trading sex for money, convictions for crimes, selling drugs, gang membership, and economic criminal behavior relative to Low Adversity youth. The full results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Percentages of Young Adult Outcomes by Class

| Total Sample | Complex (29.32%) | Environmental (12.19%) | Lower (58.49%) | X2 | Between Classes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Outcomes | |||||||

| Homelessness | 29.66 | 40.93 | 28.21 | 24.50 | 16.94 | *** | b |

| Completed HS or GED | 81.76 | 87.43 | 80.95 | 79.28 | 5.11 | ||

| Any College | 39.86 | 43.11 | 46.03 | 37.29 | 37.00 | ||

| Economic Insecurity (any) | 72.01 | 74.51 | 65.12 | 72.21 | 2.67 | ||

| Food Stamps | 69.76 | 73.04 | 60.47 | 70.07 | 4.58 | ||

| Public Housing | 19.42 | 20.81 | 15.19 | 19.56 | 1.15 | ||

| State Cash Assistance | 16.06 | 14.21 | 11.39 | 17.85 | 2.75 | ||

| Psychosocial Problems | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 65.11 | 76.50 | 66.67 | 58.79 | 16.63 | *** | b |

| PTSD Symptoms | 56.17 | 73.14 | 68.12 | 44.71 | 42.13 | *** | b,c |

| Mental Health Treatment | 30.66 | 41.18 | 25.58 | 26.60 | 14.91 | ** | a,b |

| Drug Abuse Symptoms | 42.96 | 56.29 | 52.94 | 34.05 | 25.43 | *** | b,c |

| Alcohol Abuse Symptoms | 46.29 | 53.57 | 67.14 | 37.78 | 25.01 | *** | b,c |

| Substance Abuse Treatment | 13.08 | 15.69 | 13.95 | 11.64 | 2.05 | ||

| Criminal Behaviors | |||||||

| Sold Drugs | 57.97 | 65.69 | 68.60 | 52.03 | 15.05 | ** | b,c |

| Trade Sex For Money | 16.45 | 20.10 | 25.58 | 12.77 | 11.28 | ** | b,c |

| Economic Criminal Behavior | 56.84 | 66.18 | 72.09 | 49.16 | 25.47 | *** | b,c |

| Property Crimes | 71.79 | 78.92 | 79.07 | 66.83 | 12.47 | ** | b |

| Violent Criminal Behavior | 66.43 | 69.61 | 73.26 | 63.48 | 4.35 | ||

| Gang Membership | 40.00 | 47.24 | 53.70 | 34.54 | 10.78 | ** | b,c |

| Arrested | 69.53 | 71.96 | 78.65 | 66.04 | 6.50 | * | c |

| Convicted of a Crime | 53.29 | 59.81 | 64.04 | 47.78 | 13.01 | ** | b,c |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

a = statistically significant difference between Complex & Environmental classes

b = statistically significant difference between Complex & Lower classes

c = statistically significant difference between Environmental & Lower classes

4. Discussion

This study extends prior research by providing a unique examination of the heterogeneity of adverse childhood experiences of a high-risk population, youth aging out of foster care, and exploring the implications of these differences with respect to outcomes in three domains – socioeconomic, psychosocial problems, and criminal behavior outcomes. Main findings are contextualized in existing research in this section.

4.1. ACE Profile Distinctions Among Aging Out Foster Youth

The three LCA classes were distinguished by both the accumulation and composition of childhood adversities. The Complex Adversity youth were distinguished by their experiencing higher levels of every childhood adversity except for the environmental categories. The shape of their profiles across adversities was strikingly similar to that of Lower Adversity youth, indicating comparability in composition of the kinds of adversities that both groups are exposed to. There are, however, significant differences in levels of exposure–that is, the number and proportion of youth who experienced any one adversity. This difference in levels translates into higher proportions of Complex Adversity youth with poly or multiple adversity exposure. Specifically, Complex Adversity youth experienced, on average, nearly three times as many adversities as Lower Adversity youth.

This pattern parallels what Finkelhor and colleagues (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007a) refer to as poly-victimization based on findings that maltreatment and other, caregiver-related adversities, rather than being isolated, are often patterns of jeopardy to children across multiple pathways (Finkelhor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, 2011). Paralleling ACEs research, multiple forms of trauma exposure are associated with later psychopathology, revictimization, and symptoms of developmental trauma disorder (Richmond et al., 2009; van der Kolk, 2005). Our work extends these findings by linking the identification of poly-victims within a high-risk population and following them into young adulthood. Our findings show that elevated risks for this subpopulation continue into adulthood, both in terms of risky environments (homelessness, gang affiliation) as well as behaviors (substance use, trading sex for money) and mental health symptoms that reinforce risk cascades and impair recovery.

In addition to magnitude of adversity type exposure differences, we found that the composition of ACEs matters, particularly when it comes to adversity in the environment. The Environmental Adversity class appears to have experienced not only adverse experiences within the home that led to their removal from their biological parents, but also experienced adversity that most likely occurred in their community, which we identify as spaces outside of a child’s home that she or he is likely to have relatively common exposure, including school and neighborhood. The Environmental Adversity youth may have had contact with community environments in which delinquent/criminal behaviors were more common, leading to experiences of adversity both within and outside of their households. Part of stress proliferation within life course models is operationalized through secondary stressors. For example, living in disordered neighborhoods increases psychological stress which often catalyzes maladaptive coping through problem behaviors such as substance involvement (dealing, using), antisocial affiliations, and involvement with the criminal justice system that sustain or increase risk of future adversities and lessened access to resilience resources (Dierkhising et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2013).

These findings are consistent with prior research that highlights the strong relationship between social and economic marginalization, child maltreatment, and placement in foster care (Pelton, 2015; Slack, Berger, & Noyes, 2017). Put simply, the vast majority of children enter foster care from families who suffer from poverty and many of them—the majority in this study—come from families of color who experience the additional harms associated with racial discrimination in the United States (refs???). It should not be surprising then that many youth who age out of foster care are exposed to community contexts that pose threats to their development. The community context that the Environmental Adversity class is exposed to is demarcated by violence, crime, and life-threateningly dangerous situations. Similar to previous work that identified the importance of violence exposure in a population of Chicago youth (Wright, Fagan, & Pinchevsky, 2013), we find that community violence is impactful for foster youth. Our findings indicate that maltreatment and other adversities in the home (leading to the removal from their biological parents and placed into foster care) combined with experiencing and witnessing violence in the community, places these youth at increased risk of deleterious outcomes in early adulthood.

4.2. Indications of Developmental Contexts and Trajectory Implications

Although youth aging out of foster care are at an overall increased risk of poor outcomes compared to their peers in a number of domains, our findings make evident that the risk of these outcomes is not uniformly distributed amongst these youth. Homelessness stands as a salient indicator of hazards in this developmental transition that can significantly affect successful youth development as well as safety, adult role acquisition, and mental health. According to prior studies, approximately a quarter of youth aging out of foster care report being unsheltered for at least one day within the year of leaving foster care (Pecora, et al., 2005; Shah, et al., 2015), with 36% of youth having experienced homelessness at least once by age 26 (Dworsky, Napolitano, & Courtney, 2013). The results from this present study indicate that youth who have experienced more complex ACEs histories experience homelessness at a substantially higher rate than those with less complex ACEs histories. In other words, not only are youth who have emancipated from foster care at increased risk of being homeless, but those who have experienced more types of adversities during childhood are even more so.

Previous work has found that youth with complex trauma histories were more likely to exhibit posttraumatic stress and internalizing behavior problems (Greeson, et al., 2011). Our results are congruent with these findings. The accumulation of different types of childhood adversities increases the risk of the psychosocial indicators of depression, drug dependence, and PTSD. Moreover, ACEs have been found predictive of elevated adverse experiences in adulthood, cumulative effects of both in explaining poor mental health in adulthood, and moderation effects wherein adult adverse exposures (e.g., victimization, relationship loss) exacerbate the effects of ACEs on mental health (Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene, & Borja, 2015). This highlights the need for trauma-informed training for the service providers and educators that these youth will encounter for support interventions to curb these life course trends.

Similarly, experiencing fewer childhood adversities leads to experiencing fewer poor young adult outcomes. The Lower Adversities class had the lowest proportion for all of the risk context indicators. Again, this is congruent with previous findings of ACEs and stress proliferation research that the accrual of adversity increases the risks of deleterious outcomes (Anda et al., 2006). The Lower Adversities group likely has the most overlap with the Situational Maltreatment group identified by Havlicek’s (2014) assessment of maltreatment through administrative data. This group was found to be predominantly the victims of neglect, and fewer types of maltreatment overall, similar to the Lower Adversities group. Havlicek found that the situational maltreatment group, who usually experienced maltreatment in only one developmental period, was more likely to enter out of home care at a later age than the other groups, possibly leading to reunification difficulties with their families.

It appears that experiencing the types of adversity that result in being placed in foster care in combination with having experiences living in more disordered community settings may lead to a greater impact of community dangers on youth well-being. Consistent with Foster and Brooks-Gunn’s (2009) literature synthesis, disordered community contexts, that may include poverty and racism, both cumulatively add to but also exacerbate the effects of other violence and adverse exposures. These external conditions add pathways to household based poly-victimization (Finkelhor et al., 2007b) through the individuals and experiences that they often carry. These experiences, in turn, augment the spectrum of trauma exposure as well as negative socialization. In the case of Environmental Adversity youth, this increases their likelihood of engaging in problem behaviors that bring them in contact with the criminal justice system and undermines their health and prosocial development. It is clear that the violent developmental context that these youth experienced either leads to the continuity of violence in their lives or that they are unable to escape these types of communities.

The combination of adversity experienced within the home (such as maltreatment and caregiver substance abuse) with environmental adversities leading to problem behaviors in early adulthood is an important finding of this study. The chronic stress literature, which concludes that self-regulation is disrupted as stressors accumulate, supports this understanding of the study findings (Evans & Kim, 2012). If a youth is experiencing stressors at home and also faces additional stressors in the community, the youth’s mechanisms for handling and processing these stressors can be overwhelmed. Self-regulation may become a more difficult task for the youth as the stressors accumulate. Then when presented with opportunities to engage in problem behaviors, which may be more commonplace in the community, the youth’s impaired development of self-regulatory capacity may foster greater impulsivity and engagement in dangerous behaviors (Solis et al., 2015). Therefore, it is not just the familiarity with the problem behaviors, but also the lack of self-regulation due to the accumulation of stressors that drives the trajectory from adversity experiences to participating in problem behaviors for the Environmental Adversity group.

4.3. Implications for Policy and Practice

These findings have pronounced implications for policymakers and practitioners. First, this study highlights the need for screening for a variety of types of childhood adversities. Our results are consistent with previous work that identified a subpopulation of poly-victimization of childhood adversities in another high-risk group, juvenile justice involved youth (Ford, Grasso, Hawke, & Chapman, 2013). We concur with the conclusion that the distinctive and dangerous trajectories faced by youth aging out of foster care call for specialized screening by practitioners of these youth for poly-victimization. It is clear that understanding both what a youth has experienced as well as how much exposure to a given type of stressor they have had is critical, both to allow for effective case planning as well as for understanding the types of behaviors and outcomes a youth make be at risk for in the future.

Further, screening for environmental adversities such as community violence and surviving life-threatening accidents needs specialized attention due to the distinct outcomes to which these adversities are linked. Interventions need to be developed to disrupt the trajectory from environmental childhood adversity to risk context behavior in early adulthood, with targeted programming focused on diverting these youth from criminal and related risk behaviors. These outcomes, including trading sex for money and criminal convictions, have tremendous implications for these youth as they continue into adulthood. These findings assist with the understanding of how limited resources should be targeted in order to reduce the number of youth aging out of foster care experiencing these outcomes. At a structural level, efforts to reduce economic and racial inequality that diminish community-level environmental risks will likely both decrease the number of youth entering care, and, by reducing their exposure to race- and poverty-related ACEs, improve the young adult outcomes examined in this study.

Finally, it is clear from our findings and that of prior research that the population of youth aging out of foster care is not homogeneous (Courtney, Hook, & Lee, 2012; Keller, Cusick, & Courtney, 2007). Treating all youth who are emancipating from foster care the same will not serve the youth well. Instead, targeted interventions are needed with an emphasis on the childhood adversities that each youth has experienced. There are subgroups in this population based on their ACE histories and screening for these differences can assist in developing effective service plans for each youth who is leaving foster care. An understanding of a youth’s exposure to childhood adversities can inform the independent living case plan developed for youth as they prepare to emancipate from foster care. This knowledge can also assist social workers about the types of services a youth may need. Additionally, programs that are developed to prevent such deleterious outcomes as homelessness and trading sex for money can be targeted to the youth most at risk of these outcomes.

4.4. Limitations

There are a few potential limitations of this research. The first is that information about the youths’ adverse childhood experiences were obtained via retrospective self-report. However, although there are limitations with self-report, there are also limitations with administrative data and there are probably no others who can reliably and authoritatively describe what these youth have encountered besides the youth. Previous studies of retrospective self-reported ACE accounts have demonstrated minimal reflection of respondents’ psychological state at the time of data collection, consistent statistical trends, and recall bias largely in the direction of underreporting ACE occurrences (Corso, Edwards, Fang, & Mercy, 2008; Yancura & Aldwin, 2009), including comparison of retrospective and prospective results (Hardt, Vellaisamy, & Schoon, 2010).

Additionally, this study applied an epidemiological approach to assessing prevalence of adversity exposure. This approach allowed for a fairly broad spectrum assessment of adversities. Future research may benefit from examining whether more detailed clinical information, such as frequency, duration, or severity of adversity exposures may differentially affect young adult outcomes.

A caveat with the Environmental Class is that we cannot distinguish when the adverse experiences in the community occurred, prior or after placement in the foster care system. This limits the usefulness of our finding for informing prevention strategies and calls for caution in interpreting the temporal (and therefore causal) ordering of adverse experiences. Further, the racial differences observed in the classes could be the result of several factors including differences in exposures to ACEs, variations in child welfare practices, and/or urbanicity. It is possible This is an area that future research should explore.

5. Conclusion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to evaluate differential patterns of adverse childhood exposures in youth aging out of foster care. Results suggest that not all youth who age out of foster care have the same patterns of stress/adversity exposures, and that these variations have implications for their subsequent economic, psychosocial, and risk context outcomes. The results argue for the importance of comprehensive screening for a variety of maltreatment, household, and environmental ACEs as well as targeted services based on these exposures has the potential to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Table 3.

Demographics by Class in Percentages

| Complex (29.32%) | Environmental (12.19%) | Low (58.49%) | X2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity | 35.60*** | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 42.92 | 20.69 | 23.82 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 41.04 | 60.92 | 62.26 | |

| Hispanic | 8.49 | 6.9 | 8.02 | |

| Mixed Race | 5.66 | 8.05 | 4.25 | |

| Other Race | 1.89 | 3.45 | 1.65 | |

| Gender | 12.94** | |||

| Male | 47.66 | 66.29 | 45.43 | |

| Female | 52.34 | 33.71 | 54.57 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Highlights.

Latent class analysis was used to test for adverse childhood experiences differences among youth who aged out of foster care.

Three latent classes were identified based on accumulation and composition of adversities.

Prevalence of young adult outcomes (socio-economic outcomes, psychosocial problems, and criminal behaviors) varied by class.

Implications include need for screening for broad adversities for this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support for this research through grant TL1 TR000422 and K23MH090898. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, R24 HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington. The authors acknowledge the support of the state public child welfare agencies in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin for their participation in the parent study, which received financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs, the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, the Stuart Foundation, the Walter S. Johnson Foundation, and the W.T. Grant Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahrens KR, Garrison MM, Courtney ME. Health outcomes in young adults from foster care and economically diverse backgrounds. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1067–1074. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1150. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Butchart A, Felitti VJ, Brown DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Sayedul Huq M, Sheer A, Hardt NS. The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice. 2014;3(2):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew DJ, Steele F, Moustaki I, Galbraith JI. Analysis of multivariate social science data. 2nd. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Ferguson K, Thompson S, Langenderfer L. Mental health correlates of victimization classes among homeless youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(10):1628–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, Trost K. The person-oriented versus the variable-oriented approach: Are they complementary, opposites, or exploring different worlds? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(3):601–632. [Google Scholar]

- Blome WW. What happens to foster kids: Educational experiences of a random sample of foster care youth and a matched group of non-foster care youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1997;14(1):41–53. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024592813809. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton-Jarrett R, Hair E, Zuckerman B. Turbulent times: effects of turbulence and violence exposure in adolescence on high school completion, health risk behavior, and mental health in young adulthood. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;95:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BR, Lanza ST. Who benefits most from head start? Using latent class moderation to examine differential treatment effects. Child Development. 2014;85(6):2317–2338. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12278. http://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, Mercy JA. Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. The American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1094. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Brown A, Cary C, Love K, Vorhies V. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/Midwest%20Evaluation_Report_4_10_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Cusick GR, Havlicek J, Perez A, Keller T. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 21. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/ChapinHallDocument_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Lee JS, Raap M. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 23 and 24. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/Midwest_Study_Age_23_24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Ruth G, Keller T, Havlicek J, Bost N. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/ChapinHallDocument_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Terao S, Bost N. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Conditions of youth preparing to leave state care. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2004. Retrieved from http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/CS_97.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney M, Hook J, Lee J. Distinct subgroups of former foster youth during young adulthood: Implications for policy and practice. Child Care in Practice. 2012;18(4):409–418. http://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2012.718196. [Google Scholar]

- Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, Bair-Merritt MH, Davis M, Harkins-Schwarz M, Fein JA. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(3):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising CB, Ko SJ, Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Lee R, Pynoos RS. Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2013;4:1–12. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KR, Chan G, Gelernter J, Arias AJ, Anton RF, Weiss RD, Brady K, Poling J, Farrer L, Kranzler HR. Adverse childhood events as risk factors for substance dependence: partial mediation by mood and anxiety disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworsky A, Napolitano L, Courtney M. Homelessness during the transition from foster care to adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(S2):S318–S323. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301455. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Lanza ST, Tan X. Effect size, statistical power, and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2014;21(4):534–552. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.919819. http://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.919819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self‐regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(1):43–48. http://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12013. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti MD F, Vincent J, Anda MD M, Robert F, Nordenberg MD D, Williamson MS P, David F, Spitz MS M, Alison M, Edwards BA V, Marks MD M, James S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect: The International Journal. 2007a;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007b;19(1):149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Hamby SL, Ormrod R. Polyvictimization: Children’s exposure to multiple types of violence, crime, and abuse. National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. 2011 Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/235504.pdf.

- Ford ES, Anda RF, Edwards VJ, Perry GS, Zhao G, Li C, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking status in five states. Preventive Medicine. 2011;53(3):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Grasso DJ, Hawke J, Chapman JF. Poly-victimization among juvenile justice-involved youths. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(10):788–800. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J. Toward a stress process model of children’s exposure to physical family and community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12(2):71–94. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0049-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Toro PA, Miles BW. Pathways to and from homelessness and associated psychosocial outcomes among adolescents leaving the foster care system. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(8):1453–1458. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142547. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.142547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, Wood DL. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224–e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerge R, Bilaver L, Lee BJ, Needell B, Brookhart A, Jackman W. Employment outcomes for youth aging out of foster care. University of Chicago; Chapin Hall: 2002. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/fostercare-agingout02/ [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JKP, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS, Ko SJ, Fairbank JA. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the national child traumatic stress network. Child Welfare. 2012;90(6):91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Vellaisamy P, Schoon I. Sequelae of prospective versus retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences. Psychological Reports. 2010;107(2):425–440. doi: 10.2466/02.04.09.10.16.21.PR0.107.5.425-440. http://doi.org/10.2466/02.04.09.10.16.21.PR0.107.5.425-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlicek J. Maltreatment histories of foster youth exiting out-of-home care through emancipation: A latent class analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2014;19(3–4):199–208. doi: 10.1177/1077559514539754. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077559514539754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis K, Chandler G. Adverse childhood experiences: Towards a clear conceptual meaning. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(7):1489–1501. doi: 10.1111/jan.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Cusick G, Courtney M. Approaching the transition to adulthood: Distinctive profiles of adolescents aging out of the child welfare system. Social Service Review. 2007;81(3):453–484. doi: 10.1086/519536. http://doi.org/10.1086/519536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Nurius PS, Thompson EA. Distinct stress and resource profiles among at-risk adolescents: Implications for violence and other problem behaviors. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2012;29(5):373–390. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Kim E, Nurius PS. Childhood adversity among court-involved youth: Heterogeneous needs for prevention and treatment. Journal of Juvenile Justice. 2016;5(2):68–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(10):1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(6):959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Kim H, Singer LT. Pathways linking childhood maltreatment and adult physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(6):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus user guide. 7th. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naramore R, Bright MA, Epps N, Hardt NS. Youth arrested for trading sex have the highest rates of childhood adversity: A statewide study of juvenile offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1079063215603064. 1079063215603064. http://doi.org/10.1177/1079063215603064. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Needell B, Cuccaro-Alamin S, Brookhart A, Jackman W, Shlonsky A. Youth emancipating from foster care in California: Findings using linked administrative data. 2002 Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED477793.

- Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, Borja S. Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;45:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Macy RJ. Heterogeneity among violence-exposed women: Applying person-oriented research methods. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):389–415. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Kessler RC, Williams J, O’Brien K, Downs AC, English D, Holmes K. Improving family foster care: Findings from the northwest foster care alumni study. Casey Family Programs. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.casey.org/media/AlumniStudies_NW_Report_FR.pdf.

- Pecora PJ, White CR, Jackson LJ, Wiggins T. Mental health of current and former recipients of foster care: A review of recent studies in the USA. Child and Family Social Work. 2009;14(2):132–146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00618.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pelton L. The continuing role of material factors in child maltreatment and placement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;41:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T. Transition from care: status and outcomes of youth who age out of foster care. Child Welfare. 2003;82(6):727–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JM, Elliott AN, Pierce TW, Aspelmeier JE, Alexander AA. Polyvictimization, childhood victimization, and psychological distress in college women. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14(2):127–147. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326357. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077559508326357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos LE, Mota N, Afifi TO, Katz LY, Distasio J, Sareen J. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and homelessness and the impact of axis I and II disorders. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S275–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301323. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DT, Abramson LY, Kaupie CA. The Lifetime experiences questionnaire: A measure of history of emotional, physical, and sexual maltreatment. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A, Keller T, Gowen L, Courtney M. Trauma exposure and PTSD among older adolescents in foster care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(4):545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0563-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0563-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20(1):19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MF, Liu Q, Mancuso D, Marshall D, Felver BEM, Lucenko B, Huber A. Youth at risk of homelessness: Identifying key predictive factors among youth aging out of foster care in Washington State. Washington State DSHS Research and Data Analysis Division; 2015. Retrieved from https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/SESA/rda/documents/research-7-106.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J, Garner A, Shonkoff J. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Berger LM, Noyes JL. Introduction to the special issue on the economic causes and consequences of child maltreatment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;72:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solís CB, Kelly-Irving M, Fantin R, Darnaudéry M, Torrisani J, Lang T, Delpierre C. Adverse childhood experiences and physiological wear-and-tear in midlife: Findings from the 1958 British birth cohort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(7):E738–E746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417325112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Flaherty EG, English DJ, Litrownik AJ, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB, Runyan DK. Trajectories of adverse childhood experiences and self-reported health at age 18. Academic Pediatrics. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.09.010. (n.d.) http://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby S, Finkelhor D. Community disorder, victimization exposure, and mental health in a national sample of youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(2):258–275. doi: 10.1177/0022146513479384. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022146513479384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Children’s Bureau. AFCARS Report No. 21: Preliminary FY13 estimates. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport21.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder: toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35(5):401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wade R, Shea JA, Rubin D, Wood J. Adverse childhood experiences of low-income urban youth. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e13–e20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Noh S. The long arm of community the influence of childhood community contexts across the early life course. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(8):894–910. doi: 10.2307/2137258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wright EM, Fagan AA, Pinchevsky GM. The effects of exposure to violence and victimization across life domains on adolescent substance use. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(11):899–909. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancura LA, Aldwin CM. Stability and change in retrospective reports of childhood experiences over a 5-year period: Findings from the Davis longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(3):715–721. doi: 10.1037/a0016203. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0016203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]