Abstract

Ingestible electronics have revolutionized the standard of care for a variety of health conditions. Extending the capacity and safety of these devices, and reducing the costs of powering them, could enable broad deployment of prolonged monitoring systems for patients. Although prior biocompatible power harvesting systems for in vivo use have demonstrated short minute-long bursts of power from the stomach, not much is known about the capacity to power electronics in the longer term and throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Here, we report the design and operation of an energy-harvesting galvanic cell for continuous in vivo temperature sensing and wireless communication. The device delivered an average power of 0.23 μW per mm2 of electrode area for an average of 6.1 days of temperature measurements in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. This power-harvesting cell has the capacity to provide power for prolonged periods of time to the next generation of ingestible electronic devices located in the gastrointestinal tract.

Thanks to recent advances in ingestible electronics, it is now possible to perform video capture1, electronically-controlled drug release2, pH, temperature, and pressure recording3, and heart rate and respiration monitoring4, all from within electronic pill-like capsules placed in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Recent progress in energy harvesting and wireless power transfer is offering new options to power these devices, but many are not well suited to ingestible capsules. For example, traditional harvesting sources such as thermal5, and vibration6 energy harvesting are complicated by the lack of thermal gradients in the stomach and challenges in obtaining mechanical coupling to motion sources. Wireless power-transfer via near-field7 or mid-field8 coupling is also challenging in this case, due to the unconstrained position and orientation of the capsule. Hence, there is still a strong reliance on primary cell batteries for ingestible electronics. At the same time, primary cells often require toxic materials, have limited shelf life due to self-discharge, and can result in mucosal injury9. Hence, there is a desire to explore alternative sources, particularly as the circuits scale to lower average power to enable their use in a practical system.

A few key trends have led to our work. For one, the average power demands of Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor (CMOS) technology have been scaling into the nanowatt (nW) level thanks to advanced design techniques and technology improvements10–12, reducing the demands on energy sources and enabling a wider array of harvesters. Next, advances in material design and packaging have demonstrated fully passive gastric devices that are small enough to be swallowed, but then unfold after ingestion to remain long term, up to 7 days in the stomach for ultra-long drug delivery13. Such devices could one day provide an ingestible non-invasive platform for active wireless electronic sensors that perform long term in vivo vital signs monitoring. Finally, interest in bio-compatible galvanic cells is rising, with a focus on (1) transient electronics that fully disappear at the end of their tasks14, (2) electrolytes that are supplied on demand to extend the shelf life of the cell15, (3) material selection for fully biocompatible and biodegradable cells14–17 and recently, (4) edible gastric-Mg-Cu cells, which can power near-field communication of medication compliance information to a body-worn patch for up to a few minutes18. Additionally, two in vitro studies with hours-long measurements of cells in synthetic gastric fluid-like electrolytes support the potential of long term harvesting19,20.

This has led us to investigate and demonstrate the practical use of a bio-compatible galvanic cell for powering a wireless sensor node in the GI tract in an animal model. We have developed an energy harvesting system with temperature sensing and wireless communication and have deployed it in a porcine model. In our detailed characterization experiments using a controllable load resistance, we first show an average available power density of 1.14 μW per mm2 of electrode area for a mean length of 5.0 days in the gastric cavity, limited by the residence time of our device in the stomach. Moreover, we demonstrate a power density of 13.2 nW per mm2 of electrode area in the small and large intestine. Finally, we demonstrate a fully autonomous sensor system, powered solely by the cell capable of providing central temperature measurements. The system, created from commercial semiconductor parts, performed temperature measurements and sent wireless transmissions at 920 MHz, every 12 seconds on average, to a basestation receiver located 2 m away. Here, using a boost converter to harvest the energy from the cell, we show an average power density of 0.23 μW/mm2 delivered (after all efficiency losses) to the wireless sensor microsystem for an average length of 6.1 days. Finally, we have also demonstrated the ability to utilize the harvested power to activate drug release via electrochemical dissolution of a gold membrane.

Results

Basic principle and initial characterization

The bio-galvanic cell characterized in this work consists of a redox couple formed by a dissolving metallic anode that undergoes galvanic oxidation and an inert cathode that returns electrons to the solution. In our case, the gastric or intestinal fluids of the surrounding environment form the electrolyte. The final performance of the cell is a strong function of environmental conditions that change significantly during normal gastrointestinal routines. For example, the pH, chemical composition, and heterogeneity of the stomach contents21 vary considerably throughout the day. Hence there is a need to obtain the performance of the cell directly by in vivo measurement characterization. As previous studies have noted14,22, the cathodic reaction proceeds with either hydrogen gas evolution or by the reduction of dissolved oxygen gas depending on the pH of the solution, and is usually limited by mass-transport conditions. The relevant cathodic reactions are given by:

| (1) |

| (2) |

A number of materials have been proposed as dissolving anodes, most prominently, magnesium18,23 and zinc15,19,20, which are noted for their dietary value24, low cost, ease of manufacturability, and their relatively low position in the electrochemical series25. The reaction at the anode is given by:

| (3) |

where X = Mg or Zn. The cathode, which sends electrons back into the solution, was created from pure copper metal26.

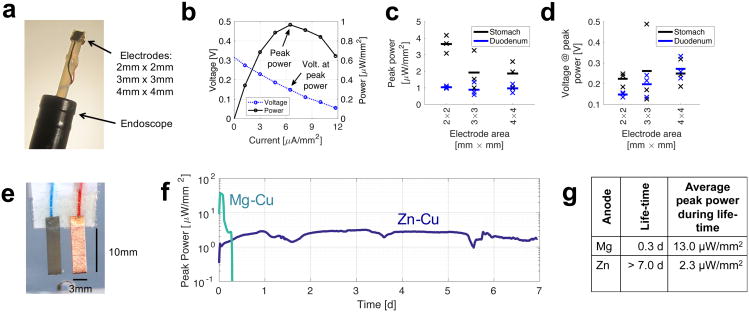

Given prior successes in utilizing magnesium, which has a higher reduction potential, for in vivo power generation18, we first considered magnesium anodes for our initial in vivo characterization evaluating the impact of electrode size. In Figure 1 (a)-(d), we characterized a Mg-Cu electrode system in a porcine model using small square electrodes of differing areas, mounted on the tip of an endoscope as shown in Fig. 1(a) (see Methods). The current density was stepped in fixed increments resulting in the voltage and power densities shown in Fig 1(b). The resulting average peak power density across all sizes shown in Fig 1(c) was 2.48 μW/mm2 in the stomach (0.97 μW/mm2 in the duodenum), and the average observed cell voltage in Fig 1(d) was 0.23 V. Consistent with the low observed cell voltage, we also noted a large amount of corrosion of the magnesium electrodes, suggesting that a greater than 24 hour lifetime would not be feasible for a magnesium-based prototype for week-long wireless measurements.

Figure 1. Initial in vivo characterization and anode comparison.

(a) Mg-Cu electrodes for probing the available power in vivo in different areas of the stomach and duodenum, with results shown in b, c and d. (b) Example of measured electrode voltage and output power density versus load current density (2 mm × 2 mm electrodes, duodenum). (c) Measured peak power density, taken at the peak indicated in b (N = 3). (d) In vivo voltage at peak power in c (N = 3), (e) Electrode configuration for anode comparison in vitro with measurements given in f and g. (f) Measured peak power density across time for both anode configurations. (g) Summary of the measured performance.

Motivated by the observations of corrosion and given the intention to evaluate extended gastric residence of these electrodes, we performed extended in vitro studies of electrode longevity (see Methods). With the configuration shown in Fig 1(e), we compared Mg and Zn anodes in side-by-side measurements using a load-sweep methodology (50 kΩ down to 150 Ω in 255 steps). Fig 1(f) shows the maximum power observed in each load resistance sweep. The Mg anode gave 1.3× higher cell voltage and 6× higher peak power density, but the Zn anode lasted much longer (more than 23×), suggesting Zn for longer term use. The combination of the experiments presented in Figure 1 allowed us to proceed to the design of a zinc-based measurement capsule to enable evaluation of the power parameters via a stand-alone device in vivo.

Characterization in the stomach environment

We created a measurement capsule (Figure 2, and Methods) to obtain detailed measurements of the performance of the Zn-Cu cell in a porcine stomach and transmit the results to a nearby basestation. The design was fully self-sufficient and wireless to avoid a tether to the outside that could reduce the practical measurement duration or impact the comfort or normal routines of the animal. A conventional coin-cell battery powered the capsule in order to avoid loading the electrodes with the demands of the circuitry during measurement, allowing a precise characterization of the cell with a separate controllable load.

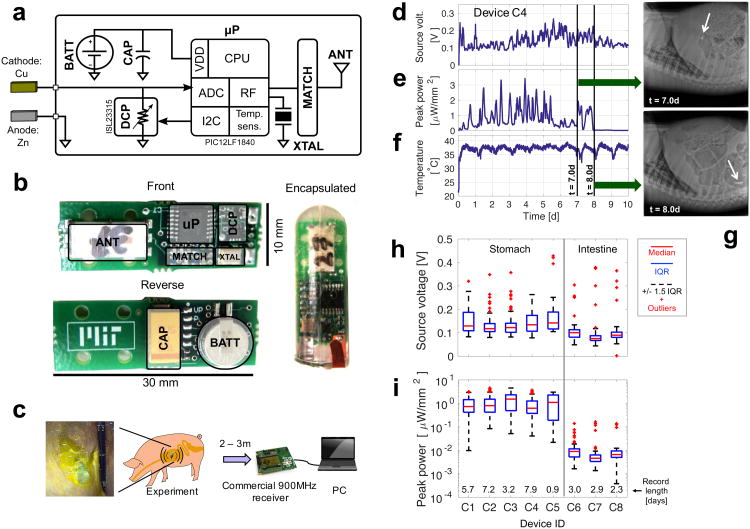

Figure 2. Electrical characterization of the gastric battery in a porcine model.

(a) Simplified architecture of the measurement system. (b) Photograph of the front and reverse sides of the system along with encapsulation using epoxy and PDMS. The PCB includes the programmable load resistor (DCP), crystal (XTAL), microcontroller (μP), RF matching network (MATCH), and antenna (ANT) on the front side, and the battery (BATT) and decoupling capacitor (CAP) on the reverse. (c) Diagram of the experimental setup, including photograph of the encapsulated pill in contact with gastric fluid inside the porcine stomach. (d, e, f) In vivo power characterization for a representative device (C4) including d: the voltage at the point of maximum power extraction during each sweep frame, e: the maximum observed extracted power in each frame and f: the measured body temperature. (g) X-rays at two time points showing passage from the stomach to the small intestine and the corresponding drop in observed power. (h) Statistical summary of the source voltage characterization data for 8 deployed devices (window size = 1h). (i) Corresponding peak power measurements for the 8 devices.

The capsule was created using all commercial low-cost semiconductor parts (Fig. 2 a and b) and consisted of: (1) an 8-bit digitally controlled potentiometer27 to set the load resistance of the cell, and (2) a microcontroller system-on-chip28 and its associated peripherals, which contained (i) a 10-bit analog-to-digital converter (ADC) that measured the electrode voltage, (ii) a temperature sensor, (iii) a wireless transmitter, and (iv) a processor that ran software code to control all of the functions.

To characterize the cell, the software was programmed sweep the load resistance through all 256 available codes (50 kΩ down to 150 Ω in 255 linear steps), taking voltage measurements at each point. Each step was held for 2 s, and at the end of a sweep, the resistor was reset to 50 kΩ and held for a further 64 s for the electrode voltage to re-equilibrate to the light-load condition before starting the next measurement (full measurement time: 576 s per sweep). The data, which included electrode voltages at each of the 256 resistor-codes, and the temperature sensor measurements, were transmitted as a Frequency-Shift-Keying-modulated, +10 dBm, 920 MHz wireless signal, to a commercial basestation receiver, mounted about 2 m away (resistance sweep methodology flow diagram and example measured waveforms illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2 respectively). We also characterized the Zn-Cu cell and measurement electronics in synthetic gastric fluid (SGF) in vitro prior to the animal experiments (data shown in Supplementary Fig. 3).

The measurement capsule was initially deployed in five animals with the results summarized in Fig. 2(d)-(i) and full data shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 and 5 (see Methods for experimental details). Due to the recognized slow motility of the porcine GI tract29,30 and the size of the capsule, the devices were retained in the animal for 7 days to 10 days without additional design considerations. During this time, the data were collected as the animal performed its normal daily routines. The traces in Fig. 2(d)-(f) correspond to an example device, and show the electrode voltage measured at the point of maximum power density for each load resistance sweep (one sample every 576 s), as well as the associated peak power density level, and the temperature recorded by the temperature sensor. Figs. 2(h) and 2(i) give the statistics of the measured peak power and optimum source voltage. Across all five stomach-deployed capsules, the mean time for which power was available, the mean Pmax, and mean voltage at Pmax were 5.0 d, 1.14 μW/mm2 and 0.149 V respectively. There was a large amount of variation in the transit time of the devices, which was anticipated and consistent with prior observations of the porcine GI tract29–31.

Interestingly, by correlating the anatomic location of the capsule determined through serial x-rays we demonstrated that the peak power drops significantly after passage through the pylorus to the small intestine. The combination of Figs. 2(e) and 3(g) shows an example of this correlation. To confirm this observation, we deployed 3 devices directly into the small intestine and tracked their passage through the colon until exit. The three devices showed an average of 13.2 nW/mm2 of peak power density and the power remained present, between 1 to 100 nW/mm2, throughout the passage time until exit (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

Harnessing power in vivo for sensing, communication, and drug delivery

To demonstrate the utility of the energy obtained, we created a second capsule powered entirely by the Zn-Cu cell (see Figure 3, and Methods). This harvested power was used for all functions of the capsule, which included temperature measurement, software control, and wireless transmission to a basestation located 2 m away. In this design (Fig. 3a) we used a commercial energy harvesting boost-converter integrated circuit (IC)32, which took energy directly from the Zn-Cu cell at low voltage (0.1 to 0.2 V) and boosted it onto a temporary storage capacitor at a higher voltage (between 2.2 and 3.3 V) for use by the circuits. The encapsulated sensor device prepared for deployment is shown in Fig 3(b).

Figure 3. Demonstration of the gastric cell powering temperature measurement, wireless transmission, and drug delivery.

(a) Architecture of the harvesting system. (b) The fabricated and encapsulated system PCB. (c) Snapshot of storage capacitor during continuous harvesting in SGF. (d) Summary of the in vivo measured performance of three deployed devices in a porcine model. (electrode area: 30 mm × 3 mm, thickness: 2 × 250μm). (e) Example of the full in vivo measurement data for a representative device (D1), including the estimated average power harvested by the board in t = 1 h windows versus time and the overall average power (red line). (f) In vivo measurement of the body temperature performed using the harvested power. (g) Received signal strength indication (RSSI) at the receiver for packets transmitted from the body using the harvested power. (h) Image of a drug release prototype device, placed on a United States dime. (i) Cross-sectional view of the device in h, where methylene blue is contained in a PMMA reservoir sealed with a 300 nm gold membrane and epoxy. (j) Demonstration of self-powered release (blue tail) from the device (yellow box) after activation in a beaker of porcine gastric fluid. Inset shows sequential images where the simulated drug is released in gastric fluid through gold corrosion. The gold membrane is intact in the beginning (t = 5 min) before triggered corrosion weakens the gold membrane causing crack formation on the film at t = 155 min (as shown by blue arrows), and ultimately the release of significant amount of methylene blue as shown at 355 min (blue color dye, shown in the red arrow). (k) Electrical profile during delivery of a pulse of charge to the release electrode. The dark line is the storage capacitor voltage and the lighter line is the voltage on the gold release electrode.

When the input source is applied, the boost converter IC pulls energy from Vin and transitions through a startup region. Once the startup is complete, the main higher-efficiency boost converter is activated and sets the OK signal, which then powers the microcontroller through a switch. From here the microcontroller transmits packets containing temperature measurement data at a variable rate depending on the input power. Fig. 3(c) shows an example of steady state operation of the capsule, where the storage capacitor is slowly charged until enough energy is available for packet transmission. The system regulates the rate by periodically sampling the voltage on VDD to determine whether to send a packet or wait for more energy to be harvested. If the sampled voltage is below 3.0 V, the system remains in a low-energy sleep mode for 4 s before attempting to sample again. If the voltage is above 3.0 V, the system transmits a packet and then returns to periodically sampling the voltage (initially 0.5 s after the packet, and then again every 4 s) to determine when to transmit the next packet. Further details on the capsule design and operation are provided in Supplementary Figs. 6, 7, and 8.

Since packet transmission is the dominant energy consumer, we used the number of transmitted packets in a given window length (twindow) to estimate the overall amount of energy delivered to the load. Each packet is 176 bits long including preamble and headers and is transmitted at 50 kbps, resulting in a 3.5 ms packet transmitted at +10 dBm. Ex vivo, a laboratory power supply was used to characterize the energy consumed by the capsule in transmitting each packet as a function of the systemVDD, Epkt = f(VDD). Then during the in vivo experiment, the number of packets transmitted during a given interval was used to determine the average power (Psys,avg)delivered to the load using:

| (4) |

VDD[m]was the measured system VDD at the beginning of each packet transmission – information that was transmitted along with the temperature measurement data. To obtain an accurate packet count despite the possibility of dropped packets, we also transmit an internally generated packet count to the basestation along with the other measurements.

The system was deployed in 3 animals and the results are summarized in Fig. 3(d) (full measurements in Supplementary Fig. 9). Fig 3(e) shows the power delivered from the cell to the load using eqn. (3), with twindow = 1 h. Fig 3(f) shows the measured temperature sensor data, and Fig 3(g) shows the RF signal strength seen by the receiving basestation for each packet. Of note was that temperature readings below the expected core or central temperature were observed coinciding with daytime hours and also near feeding times (Fig. 3f) likely representing transient temperature decrement associated with ingestion of foods and liquids. The disconnected regions in the figures represent periods for which electrical power was not sufficient to send wireless packets, for example, due to variations in both the fluidic environment of the stomach and the position of the capsule within it. On average, packets were received in 91% of the 1 h time slots during the three experiments. Across all of the experiments, the devices operated for a mean of 6.1 days, delivering an average power of 0.23 μW per mm2 of electrode area to the load, and transmitting packets with temperature measurements every 12 seconds.

To further demonstrate the utility of the energy harvested by the system, we designed and fabricated a device for drug release that can be triggered with the harvested energy, as shown in Fig 3(h), and tested this device in vitro with physiologic gastric fluid (See Methods for the details of device fabrication). The device, as shown in Fig 3(i), encapsulates a model drug (in this case, methylene blue) in a PMMA reservoir (2 mm × 1 mm × 1.5 mm) that is sealed with a 300 nm thick gold membrane. The release is achieved via electrochemical dissolution of the membrane, as demonstrated previously by Santini et. al33. The gold membrane, which is otherwise inert in the gastric environment, can be chemically corroded when the potential is raised (+1.04 V with respect to Saturated Calomel Electrode) to allow formation of water-soluble chloro-gold complexes34. Our results show that the device remains intact when it is connected to the system ground (shorted to the zinc electrode) in physiologic gastric fluid (See Methods for experimental details). Upon activation via the application of discharge of voltage from 2.0 to 2.3 V with respect to zinc system ground, the corrosion of the gold weakens the membrane integrity, causing crack formation that is visible at t = 155 minutes (blue arrow, shown in the middle inset of Fig. 3j), and ultimately the visible release of the contents (indicated with red arrow at the right inset of Fig. 3j.) through the corroded membrane. The voltage profile plotted in Fig 3(k) shows the discharge characteristics that gradually activate the release. The initial shallow ramp from 3.15 V to 2.95 V represents the microcontroller boot-up followed by temperature measurement. The steep drop from 2.95 V to 2.3 V represents the packet transmission, and the more slow discharge from 2.3 V to 2.0 V represents charges delivered to the gold electrode. With the 220 μF storage capacitance, this represents 66 μC of charge delivered to the electrode per pulse. The pulse ends when the boost converter toggles the OK signal low (due the storage voltage declining below the threshold), which deactivates the microcontroller and release electrode switch, and allows the storage capacitor to begin charging in preparation for the next cycle. The average pulse rate during the experiment was 11.9 s, and charge delivery rate was 5.5 μC/s. For the designed size of 2 mm × 1 mm active gold area (with 300 nm thickness), the total theoretical charge necessary to completely dissolve the electrode was 17.0 mC, and hence an ideal dissolution time of 51 min. In gastric fluid, it is expected that side reactions can occur on the electrode surface resulting in a longer release time, hence the observed time of 155 min.

Discussion

Ingestible electronics have an expanding role in the evaluation of patients35. The potential of applying electronics or electrical signals for treatment is being explored36 and the potential for long term monitoring and treatment is being realized through the development of systems with the capacity for safe extended gastrointestinal residence13,37. Energy alternatives for GI systems are needed to enable broad applicability, especially given size and biocompatibility constraints coupled with the potential need for long-term power sources and low cost systems.

Here we report the in vivo characterization of a galvanic cell composed of inexpensive biocompatible materials, which are activated by GI fluid. We have demonstrated energy harvesting from the cell for up to 6 days (average power 0.23 μW/mm2) and using this energy we have developed a self-powered device with the capacity for central temperature measurement and wireless transmission from within a large animal model. The combining of the cell with a boost converter in the energy harvesting IC allowed the system to power these more complex electronics, even as the cell voltage and power level varied during the experiments.

The device we have fabricated could be rapidly implemented for the evaluation of core body temperature and for the evaluation of GI transit time given the differential temperature between the body and the external environment. A recent study evaluating data collected from 8682 patients found that peripheral temperature readings did not have acceptable clinical accuracy to guide clinical decisions38. Hence, continuous automated central temperature measurements via a wireless ingestible system may provide significant clinical benefit. We have also demonstrated, via a custom designed drug release device, that such an energy harvesting method could be used to activate drug delivery via a gold membrane corrosion mechanism. This proof of concept could ultimately allow the incorporation drug delivery in the ingestible electronic capsule.

Furthermore, we have characterized and demonstrated the capacity for harvesting from across the GI tract including stomach, small intestine and colon. Interestingly, the available power density ranged between a few μW/mm2 down to a few nW/mm2 across the GI tract. The reduced power in the intestine could potentially be explained by anatomical variation compared with the stomach, wherein diffusion is impaired by close contact with the intestinal walls. Further development will be required to delineate the exact causes and could lead to an improved design. In the meantime, this observation may guide future development of gastrointestinal resident electronic power harvesting systems according to their targeted anatomic location. For example, there may be a need for greater storage capability to carry energy from the stomach, or depending on the application, it may be necessary to support even lower power modes.

Our electrode area in this study was limited by the availability of a nanowatt-level commercial harvester. Nevertheless, the total elemental zinc present in our largest tested electrode (30 mm × 3 mm × 0.25 mm) was 161 mg. Assuming extreme case of full dissolution across the six-day experiment, the average zinc ion deposit rate for this electrode would be 27 mg/day. This amount is below the US Food and Nutrition Board recommended upper limit UL = 40 mg/day24, and in line with levels found in over-the-counter zinc supplements (15, 30, and 50 mg/day dosings are commonly available). Looking ahead, we would expect that a custom designed system would be able to target much lower power levels and hence integrate smaller electrodes and less zinc deposition than we have tested here.

Research in ultra-low-power electronics continues to push the boundaries of the average power consumption, and already provides a range of options for circuits that could be adapted for use in GI applications at the nanowatt level. For example, energy harvesters (for sub 10 nW available power10–12), ADCs and signal acquisition circuits (under 10 nW39,40), far field wireless transmitters (under 1 nW standby41), and mm-scale sensor nodes with sensing, processing (sub nW standby42). Such systems could allow the electrode area to scale to just a millimeter or two on a side, and could enable broad applications for extended power harvesting from alternative cells for long term monitoring of vital signs4 and other parameters in the GI tract, especially with the introduction of devices that are deployed endoscopically43 or self-administered13 and have the capacity to reside in the gastric cavity for prolonged periods of time.

Though sufficient for our animal studies, one limitation is the size of the capsule. Without a clear picture of the expected voltage and power levels in vivo at the outset, achieving further miniaturization as part of this study would have been challenging. Given our measured results, and with further engineering development, for example, to create a custom single-chip Application Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) and to apply enhanced packaging techniques like component stacking, the design could potentially be miniaturized by 3 to 5× as compared to the volume of the currently presented hardware. In addition, future work should strive to match animal behavior information, such as feeding and motion data, with the measured power level and observed physiologic signals in order to better understand the sources of variations observed here.

One further limitation is the physical design of the electrochemical cell. Our focus was on powering robust in vivo measurements over longer periods of time compared to previously reported cells. However, additional effort should be applied to improve the voltage and power of the cell, for example by integrating membranes to improve proton exchange20 while controlling corrosion of the electrodes44. In addition, further improving the efficiency of low-voltage boost converters to ultra-low power levels will facilitate demonstration with smaller electrode areas (approaching 1 mm × 1 mm), or allow harvested operation across the entire GI tract. One additional area of research development will include the development of systems that can be safely retained in the GI tract to enable self-powered monitoring on the order of weeks, months or even years following a single ingestion. Such development should focus on solving material, packaging, and interfacial challenges in order to design a capsule for eventual human trials.

Methods

Magnesium, zinc and copper electrode fabrication and attachment

All electrodes were created from pure metal foils (Alfa Aesar, 0.25 mm thick) and cut to the specified length and width dimensions to within ± 10%. Attachment of the zinc and copper electrodes to wires or to the PCBs was performed with standard solder and flux, whereas magnesium, which is not solderable, was attached with 2-part silver conductive epoxy (8331, MG Chemicals).

In vivo characterization of magnesium-copper system

Electrodes (with attached wires) were fixed via thermoplastic adhesive to opposite sides of a 3D-printed post (30 mm long, 3.8 mm diameter) for easy mounting on an endoscope for guidance into the stomach and duodenum. The electrodes were connected by a ∼3m long cable which passed through the lumen of the endoscope to a Keithley 6430 source-meter, which executed the specified current steps and voltage measurements from outside the animal.

Electrode longevity comparison

Electrode anode and cathode (with attached wires) were placed side-by-side (3 mm separation) on a polystyrene support and fixed using 2-part epoxy (20845, Devcon), with 10 mm electrode length exposed. The electrode pairs were submerged in a pH 4 buffer solution (33643, Fluka Analytical) and measured using the same electronics as the characterization capsule, described below.

Characterization and demonstration capsule fabrication

The printed circuit boards (PCB) for the capsules were 4-layer FR4, with 1 oz copper metallization. The electrodes were soldered onto the PCB for protrusion outside the encapsulation. Encapsulation was performed as a 2-step process. Prior to polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molding, the boards were fully coated in 2-part epoxy (1-2 mm thick) to act as sealant against moisture and prevent fluid from entering the device via the protruding electrodes. The outer layer was PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning), selected for biocompatibility with the stomach environment and molded into a capsule shape to facilitate passage through the GI tract. The electrodes protruded through the back of the encapsulated device and were bent around towards the front and secured to the outer layer of the PDMS with 2-part epoxy (20845, Devcon).

In vivo characterization

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care. In vivo porcine studies were performed in female Yorkshire pigs aged between 4 and 8 months and weighing approximately 45-50 kg. The porcine model was specifically selected given prior observations noting slower transit time and thereby providing the capacity for extended residence of a macroscopic device in the GI tract29,30. Animal sample size was guided by prior work demonstrating proof-of-concept studies with gastrointestinal drug delivery and sensor systems4,13,45. In vivo experiments were not blinded or randomized. Prior to endoscopy or administration of the prototypes the animals were placed on a liquid diet for 48 hours. The animals were fasted overnight immediately prior to the procedure. On the day of the procedure for the endoscopic characterization studies the animals received induction of anesthesia with intramuscular injections of Telazol (tiletamine/zolazepam) 5 mg/kg, xylazine 2 mg/kg, and atropine (0.04 mg/kg), the pigs were intubated and maintained on inhaled isoflurane 1-3%. For the deployment of the capsule prototypes the animals were sedated with the intramuscular injections as noted above. The esophagus was intubated and an esophageal overtube placed (US Endoscopy). The prototypes were delivered directly to the gastric cavity or endoscopically placed in the small intestine through the overtube. Prototypes were followed with serial x-rays. A total of five stomach-deposited characterization devices were evaluated in five separate pig experiments. One device (C1) was retrieved early from the small intestine after recording for 8.3d and passing through the pylorus. Two devices stopped their recording early, secondary to leakage in the PDMS/epoxy encapsulation: one after 7.1 days of measurement but prior to reaching the small intestine (C2), and one after 10.1 days of measurement, including 8.0 days in the stomach and 2.1 days spent in the small intestine (C4), as estimated by the observed power density drop. Two devices (C3 and C5) recorded all the way to exit (8.8d and 7.5d of recording). The four devices reaching the small intestine exhibited significant power density drops co-inciding with extra gastric location. Three additional characterization devices (C6 to C8) were deployed directly into the duodenum to confirm the power density differential, all of which recorded from deposition until exit (3.0d, 2.9d, and 2.3d respectively). Finally, three self-powered temperature devices (D1 to D3) were evaluated in three separate pig experiments (6.8d, 6.6d, and 4.7d respectively). All three self-powered devices were deployed in the gastric cavity. Before placing the devices, the electrodes were temporarily supplied with 3 V from an external source in order to guarantee cold-start of the harvester and to obtain a temperature reading from the room for offline calibration of the temperature measurement data. During and after the experiment, we did not see evidence of toxicity from clinical observation. While in place animals were maintained on a liberalized diet.

Drug release prototype fabrication

Drug cavities and the substrate of the release prototype were first defined with a conventional carbon dioxide laser engraver (Universal Laser Systems VLS 6.60, Engraving Systems LLC) on a 1.5 mm thick poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) board (KJ-35052050, McMasterCarr). A 300 nm thick gold layer was deposited on a separate PMMA substrate using an electron beam evaporator and a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) film was adhered to the gold surface. The gold/PVA layer was then peeled off from the substrate and transferred to the delivery device to seal the cavity by stamping the device into a thin layer of low viscosity epoxy (EPO-TEK 301-1, Epoxy Technology). Here the PVA film acts as a dissolvable temporary support layer to provide mechanical rigidity for the 300 nm thin gold film during the transfer process. Methylene blue (M9140, Sigma Aldrich) is then added to the reservoir, accessible from the bottom of the device, before it is sealed with high viscosity epoxy (20445, Devcon). The relatively high viscosity prevents the infiltration of the sealant to the filled cavity. Following curing of the epoxy, the sealed device was put into DI water to dissolve the temporary PVA film and subsequently dried in air. An electrical connection was then made to the gold layer using conductive epoxy (CW2400, Circuitworks). Finally, all conductive areas except the membrane portion of the gold layer covering the drug cavity were insulated with medium-viscosity UV-curable epoxy (EPO-TEK OG116-31, Epoxy Technology) and subsequently UV cured.

Demonstration of activated drug release

The release prototype and zinc and copper electrodes (preparation as described earlier with 30 mm length and 3 mm width) were submerged in physiologic gastric fluid. Gastric fluid was endoscopically extracted from live Yorkshire pigs that were on liquid diet two days prior to the procedure. The drug release prototype was connected to a controller board described earlier, which harvests and releases the captured energy to the prototype. The demonstration proceeded in two phases, (1) a control phase, and (2) the release phase. In the control phase, the integrity of the device is first tested submerged in gastric fluid (47 hours in our case), while the potential of the gold membrane was maintained at the system ground (0 V relative to the zinc). Upon determination of its mechanical integrity, and examining the membrane for leakage, the reservoir along with harvesting electrodes were placed in a fresh sample of gastric fluid for the release phase. In this phase, the controller was configured to short the reservoir electrode to the system VSTOR to deliver packets of charge at the end of each wake-up interval in order to corrode the electrode. The device submerged in gastric fluid was observed through a macroscopic lens, and the electrical profile was collected through an oscilloscope.

Data collection

A commercial transceiver evaluation board (SmartRF TrxEB, Texas Instruments) was used to receive the 900 MHz FSK packets transmitted from the capsules. For the large animal experiments, the board and its antenna were mounted above the steel cage area that housed the animals (about 2 m above the ground). The transceiver board was connected via USB cable to a laptop that saved the raw packet information for later offline processing in MATLAB®.

Code availability

The microcontroller code that was used in this study is available in Figshare with the identifier “doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.4451420”46. Proprietary code from Microchip Inc used in the microcontroller is not publicly available.

Data availability

Source data for the figures in this study are available in Figshare with the identifier doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.4451420 (ref. 46). The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Haupt, M. Jamiel, and A. Hayward for help with the in vivo porcine work. We also thank A. Paidimarri for helpful discussions. This work was funded by Texas Instruments, the Semiconductor Research Corporation's Center of Excellence for Energy Efficient Electronics, and the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission, (to A.C.) and NIH Grant EB-000244, and the Max Planck Research Award, Award Ltr Dtd. 2/11/08, Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung Foundation (to R.L.) and the Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women's Hospital (to G.T.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: PN, DE-D, DG, YLK, NR, RL, AC, GT conceived and designed the research. PN, DE-D, SM, YLK, NR constructed prototypes for testing. PN, DE-D, DG, YLK conducted in vitro characterization. PN wrote the software for the capsules and offline processing the packets. PN, DE-D, DG, YLK, CC, LB, GT performed in vivo pig experiments. PN, DE-D, DG, YLK, NR, RL, AC, GT analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that provisional patent application no. 62/328,084, covering a portion of this work, has been filed with the USPTO on April 27, 2016.

References

- 1.Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. doi: 10.1038/35013140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Schaar PJ, et al. A novel ingestible electronic drug delivery and monitoring device. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.03.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maqbool S, Parkman HP, Friedenberg FK. Wireless capsule motility: Comparison of the SmartPill(R) GI monitoring system with scintigraphy for measuring whole gut transit. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2167–2174. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traverso G, et al. Physiologic Status Monitoring via the Gastrointestinal Tract. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141666–e0141666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramadass YK, Chandrakasan AP. A Battery-Less Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting Interface Circuit With 35 mV Startup Voltage. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2011;46:333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dagdeviren C, et al. Conformal piezoelectric energy harvesting and storage from motions of the heart, lung, and diaphragm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:1927–1932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317233111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters BH, Sample AP, Bonde P, Smith JR. Powering a Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) With the Free-Range Resonant Electrical Energy Delivery (FREE-D) System. Proc IEEE. 2012;100:138–149. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho JS, et al. Wireless power transfer to deep-tissue microimplants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:7974–7979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laulicht B, Traverso G, Deshpande V, Langer R, Karp JM. Simple battery armor to protect against gastrointestinal injury from accidental ingestion. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:16490–16495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418423111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercier PP, Lysaght AC, Bandyopadhyay S, Chandrakasan AP, Stankovic KM. Energy extraction from the biologic battery in the inner ear. Nat Biotech. 2012;30:1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung W, et al. An Ultra-Low Power Fully Integrated Energy Harvester Based on Self-Oscillating Switched-Capacitor Voltage Doubler. 2014;49:2800–2811. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Damak D, Chandrakasan AP. A 10 nW-1 uW Power Management IC With Integrated Battery Management and Self-Startup for Energy Harvesting Applications. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2016:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, et al. A pH-responsive supramolecular polymer gel as an enteric elastomer for use in gastric devices. Nat Mater. 2015;14:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/nmat4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin L, et al. Materials, Designs, and Operational Characteristics for Fully Biodegradable Primary Batteries. Adv Mater. 2014;26:3879–3884. doi: 10.1002/adma.201306304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KB, Lin L. Electrolyte-based on-demand and disposable microbattery. J Microelectromechanical Syst. 2003;12:840–847. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garay EF, Bashirullah R. Biofluid Activated Microbattery for Disposable Microsystems. Microelectromechanical Syst J. 2015;24:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YJ, Chun SE, Whitacre J, Bettinger CJ. Self-deployable current sources fabricated from edible materials. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:3781–3788. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20183j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafezi H, et al. An Ingestible Sensor for Measuring Medication Adherence. Biomed Eng IEEE Trans. 2015;62:99–109. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2341272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimbo H, Miki N. Gastric-fluid-utilizing micro battery for micro medical devices. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2008;134:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostafalu P, Sonkusale S. Flexible and transparent gastric battery: Energy harvesting from gastric acid for endoscopy application. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;54:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Maio S, Carrier RL. Gastrointestinal contents in fasted state and post-lipid ingestion: In vivo measurements and in vitro models for studying oral drug delivery. J Control Release. 2011;151:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy OZ, Wehnert RW. Improvements in biogalvanic energy sources. Med Biol Eng. 1974;12:50–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02629834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.She D, Tsang M, Kim JK, Allen MG. Immobilized electrolyte biodegradable batteries for implantable MEMS. Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), 2015 Transducers - 2015 18th International Conference on. 2015:494–497. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, K, Aresenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes WM. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kear G, Barker BD, Walsh FC. Electrochemical corrosion of unalloyed copper in chloride media––a critical review. Corros Sci. 2004;46:109–135. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Datasheet Low voltage digitially controlled potentiometer, ISL23315. Intersil; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datasheet 8-Bit Flash Microcontroller with XLP Technology, PIC12LF1840T39A. Microchip; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snoeck V, et al. Gastrointestinal transit time of nondisintegrating radio-opaque pellets in suckling and recently weaned piglets. J Control Release. 2004;94:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hossain M, Abramowitz W, Watrous BJ, Szpunar GJ, Ayres JW. Gastrointestinal Transit of Nondisintegrating, Nonerodible Oral Dosage Forms in Pigs. Pharm Res. 7:1163–1166. doi: 10.1023/a:1015936426906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traverso G, et al. Microneedles for Drug Delivery via the Gastrointestinal Tract. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:362–367. doi: 10.1002/jps.24182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Datasheet Ultra Low Power Boost Converter with Battery Management for Energy Harverster Applications, BQ25504. Texas Instruments; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santini JT, Cima MJ, Langer R. A controlled-release microchip. Nature. 1999;397:335–338. doi: 10.1038/16898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santini J, Jr, Richards AC, Scheidt R, Cima MJ, Langer R. Microchips as Controlled Drug-Delivery Devices. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:2396–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singeap AM. Capsule endoscopy: The road ahead. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:369. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reardon S. Electroceuticals spark interest. Nature. 2014;511:18. doi: 10.1038/511018a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traverso G, Langer R. Perspective: Special delivery for the gut. Nature. 2015;519:S19–S19. doi: 10.1038/519S19a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niven DJ, et al. Accuracy of peripheral thermometers for estimating temperature: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:768–777. doi: 10.7326/M15-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harpe P, Gao H, Dommele Rv, Cantatore E, Roermund A, van HM. A 0.20 3 nW Signal Acquisition IC for Miniature Sensor Nodes in 65 nm CMOS. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2016;51:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yaul FM, Chandrakasan AP. A 10 bit SAR ADC With Data-Dependent Energy Reduction Using LSB-First Successive Approximation. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2014;49:2825–2834. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paidimarri A, Ickes N, Chandrakasan AP. IEEE ISSCC Dig Tech Papers. 2015. A +10dBm 2.4GHz transmitter with sub-400pW leakage and 43.7% system efficiency; pp. 1–3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fojtik M, et al. A Millimeter-Scale Energy-Autonomous Sensor System With Stacked Battery and Solar Cells. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2013;48:801–813. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kethu SR, et al. Endoluminal bariatric techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapoport BI, Kedzierski JT, Sarpeshkar R. A Glucose Fuel Cell for Implantable Brain-Machine Interfaces. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38436–e38436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoellhammer CM, et al. Ultrasound-mediated gastrointestinal drug delivery. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:310ra168–310ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nadeau P, et al. Data for Prolonged energy harvesting for ingestible devices. 2017. Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for the figures in this study are available in Figshare with the identifier doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.4451420 (ref. 46). The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.