Abstract

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the major factors restricting the efficacy of chemotherapy. Several pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to MDR, including the overexpression of drug efflux pumps. Strategies to overcome MDR have mostly focused on the modulation of cellular resistance, such as the use of drugs and drug delivery systems to inhibit or bypass drug efflux pumps. Much less attention has been devoted to microenvironmental resistance, both mechanistically and therapeutically. As a reciprocal response to cellular MDR, cancer cells might remodel their microenvironment, resulting in changes in vascularization and oxygenation, as well as in the expression of cell adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix components and matrix metalloproteinases. We here describe the basic principles of cellular and microenvironmental MDR, and discuss drug delivery systems and drug targeting strategies to more efficiently deal with cellular and microenvironmental resistance.

1. Introduction

Multidrug resistance (MDR) refers to the cross-resistance of cells against (chemo-) therapeutic drugs. Several cellular phenomena contribute to MDR, including the overexpression of drug efflux pumps, the induction of cell survival pathways and the inability to induce apoptosis. The former undoubtedly is a key cellular event in MDR. It is based on the overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport proteins, such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp/ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP/ABCC1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) [1]. Apart from cellular events, also microenvironmental factors such as remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) have been implicated in MDR [2]. In this context, it is reasonable to assume that in many cases, cellular and microenvironmental resistance go hand in hand. Almost regardless of the exact pathophysiological nature of MDR, the net end result is a significantly reduced accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs in target cells, which for obvious reasons substantially compromises response rates and therapeutic outcomes.

Nanomedicine-based drug delivery systems (DDS) have been extensively employed to improve the biodistribution and the target site accumulation of chemotherapeutic agents [1]. Because of their shape and size, nanomedicines are less prone to renal excretion and hepatic degradation. Consequently, they are able to circulate for prolonged periods of time and to accumulate in tumors (and at sites of inflammation) via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, while avoiding disposition in healthy organs and tissues. An additional feature resulting from their shape and size is that nanomedicines are not taken up by cells via passive diffusion, as are the majority of standard (i.e. low-molecular-weight drug molecules), but via endocytosis or macropinocytosis. This enables them to bypass drug efflux pumps, at least to some extent. Because of this and several other mechanisms, nanomedicines may play an increasingly important role in combating MDR.

In the present perspective, we discuss delivery systems and targeting strategies that can be employed for overcoming MDR, focusing not only the altered cellular characteristics of MDR cells, but also on the reciprocal interactions between MDR cells and their microenvironment.

2. Overcoming cellular MDR

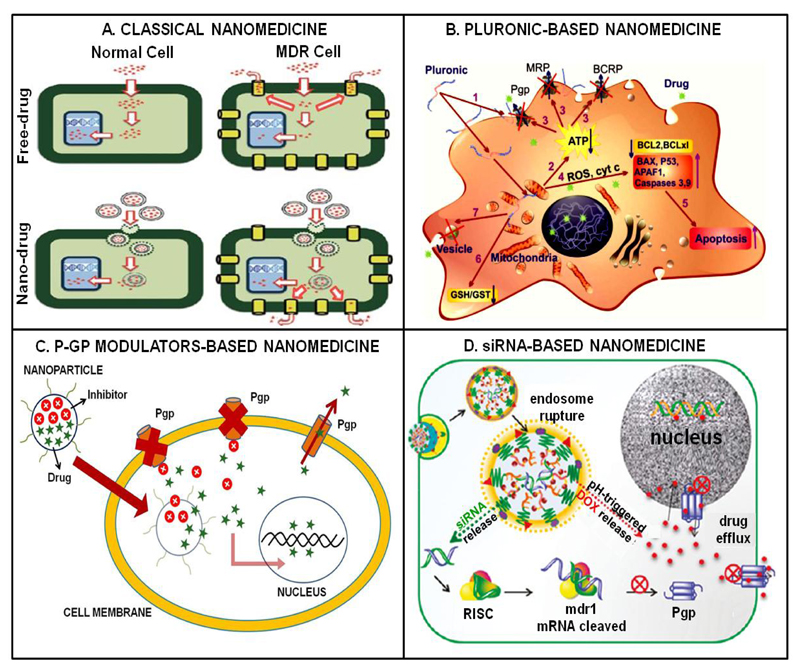

Several nanomedicine-based strategies have been evaluated to overcome MDR at the cellular level. These include (i) exploitation of endocytosis; (ii) use of Pluronic nanocarriers; (iii) co-delivery of MDR modulators together with chemotherapeutic drugs; and (iv) co-delivery of anti-MDR siRNA together with chemotherapeutic drugs.

Regarding the former, nanomedicines are known to be taken up via endocytosis or macropinocytosis, thereby bypassing drug efflux pumps in the cellular membrane (Figure 1A). A nice example of a study exploiting this notion was published by Kievit and colleagues, who showed that polyethylene glycol (PEG) -coated iron oxide nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with doxorubicin (DOX) via pH-sensitive hydrazone bonds might be favorable for delivering DOX into multidrug resistant C6 glioma cells. This formulation allowed for efficient DOX loading, as well as for controlled drug release in endo- and lysosomes upon endocytosis, together resulting in a significantly higher cytotoxicity as compared to free DOX [3].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of nanomedicine-based strategies for overcoming cellular MDR. (A) Classical approach using drug-loaded nanomedicines which are endocytosed to bypass drug efflux pumps. (B) Pluronic-based nanomedicines possess multiple intrinsic anti-MDR properties which are schematically indicated by numbers (see [4] for details). (C) Combinatorial nanotherapy with a drug efflux pump inhibitor and a chemotherapeutic agent. (D) Co-encapsulation of anti-MDR siRNA together with a chemotherapeutic drug. Images adapted, with permission, from [1, 4 and 12].

Pluronics are poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO-PPO-PEO) block copolymers which affect several key processes involved in cellular MDR, including the function of drug efflux pumps [4] (Figure 1B). Consequently, incorporating chemotherapeutic drugs in Pluronic-based micelles might be a viable strategy to overcome MDR. In this regard, Chen et al. prepared mixed micelles based on Pluronic F127 and Pluronic P105 coupled to methotrexate (F127/P105-MTX). They evaluated the efficacy of F127/P105-MTX Pluronic micelles in resistant KBv epidermoid cells and mouse models, and observed improved efficacy as compared to control formulations both in vitro and in vivo [5].

Combination therapy with nanomedicines encapsulating MDR inhibitors and chemotherapeutic agents is another interesting approach to tackle MDR (Figure 1C). In this regard, Patel et al. co-encapsulated tariquidar (TAR; a third generation of Pgp inhibitor) and paclitaxel (PTX) in a liposome-based nanomedicine formulation, and evaluated its efficacy in sensitive and taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells (SKOV-3 and SKOV-3TR). As compared to free PTX, the IC50 values of TAR-PTX-liposomes were 1.5 and 80 fold lower in SKOV-3 and SKOV-3TR, respectively [6].

Another strategy which has been increasingly employed to overcome cellular resistance is based on the co-delivery of anti-MDR siRNA with chemotherapeutics (Figure 1D). An extensive study confirming the potential of this approach was published by Meng and colleagues, who co-loaded mesoporous silica NPs with Pgp-specific siRNA and with DOX. This combinatorial nanoformulation was extensively tested in vitro and in vivo, and turned out to be significantly more efficient in inhibiting the growth of MCF-7/MDR breast cancer cells and xenografts than were all relevant control formulations [7].

3. Targeting microenvironmental MDR

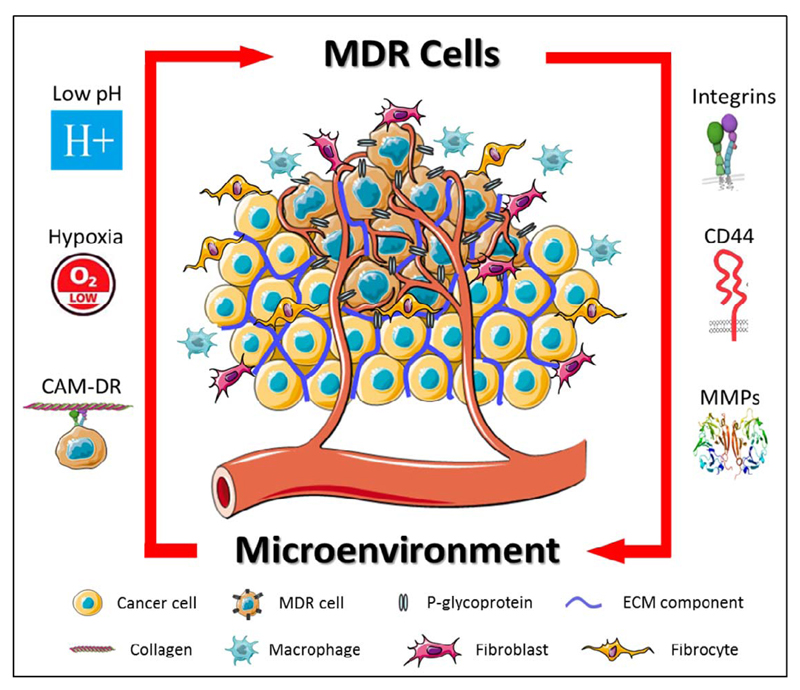

Besides at the cellular level, MDR may also present at the level of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [2]. Because of its heterogeneity and complexity, and particularly because of its key role in enabling (or disabling) efficient drug delivery, the TME should not be neglected when aiming to develop better treatments for resistant cancers. In this context, also direct and indirect interactions between MDR cells and the TME have to be considered, as they might trigger multiple signaling pathways which modulate the expression of drug efflux pumps and/or of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (Figure 2). A better understanding of such reciprocal interactions will result in more efficient systems and strategies for overcoming MDR.

Figure 2.

The reciprocal interaction between cancer cells and their tumor microenvironment (TME) is schematically depicted. The microenvironment promotes cellular resistance via mechanisms such as low pH, hypoxia and cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR). Vice versa, cancer cells promote microenvironmental resistance via the expression of cell adhesion molecules and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

Abnormal vasculature results in inefficient delivery of nutrients and oxygen to cancer cells. Under these circumstances, hypoxic regions typically develop within tumors. Hypoxia results in the upregulation and activation of the heterodimeric transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which localizes to the nucleus under hypoxic conditions. Changes in HIF1-regulated gene expression trigger several signaling pathways which contribute to an MDR phenotype, as exemplified by the fact that a functional HIF-1 binding site is present in the promoter region of the Pgp gene (MDR1) [8]. The relatively low pH which is typically present in the TME also directly results from hypoxia and leads to protonation of weak-base hydrophobic anti-cancer drugs. This reduces cellular uptake and thereby contributes to drug resistance. Normalizing tumor blood vessels is considered to be an interesting strategy to overcome this problem [9]. When given at intermediate doses, antiangiogenic agents induce vascular normalization and they might thereby reduce the impact of hypoxia and low extracellular pH on drug uptake and performance. Evidence for vascular normalization and enhanced oxygenation has been provided by Jain and colleagues, showing that 20 out of 40 glioblastoma patients treated with the antiangiogenic agent cediranib presented with improved tumor perfusion and oxygenation, and consequently responded better to chemoradiotherapy [10].

Another microenvironmental MDR mechanism results from enhanced cell adhesion to the ECM. Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane cell adhesion receptors and multiple integrin subunits are overexpressed by MDR cells. Damiano and colleagues for instance demonstrated that α4β1 integrin is overexpressed on DOX- and melphalan-resistant 8226 myeloma cells, and that integrin-mediated adhesion suppresses apoptosis, giving rise to the term cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) [11]. Based on this notion, integrin targeting might be an interesting strategy for combating MDR. Many peptides moieties are available for specific integrin binding, including RGD, which binds with relatively high affinity to αvβ3. This integrin plays an important role in tumor neovascularization and metastasis, and likely also in MDR. Initial proof-of-concept for RGD-mediated drug delivery and anti-MDR therapy has been provided by Xiong and Lavasanifar, who developed RGD-modified micelles for co-delivery of Pgp-siRNA and DOX [12]. DOX accumulation in resistant αvβ3 integrin- and Pgp-expressing MDA-MB-435 cells was assessed using confocal microscopy. The results showed that the highest nuclear accumulation of DOX was achieved upon treatment with RGD-targeted micelles containing both DOX and Pgp-specific siRNA. Treatment with non-targeted-micelles was also evaluated, but these turned out to be unable to deliver high amounts of DOX to the nucleus. In addition, efficient accumulation of RGD-targeted micelles was observed in MDA-MB-435 tumors in mice, underlining the potential value of integrin targeting for overcoming MDR [12].

CD44-mediated cell adhesion has also been implicated in MDR. CD44 is the receptor for another ECM component, hyaluronic acid (HA), and its overexpression has been linked to Pgp-mediated MDR. HA-conjugated NPs might serve as a potential therapy approach for CD44-expressing MDR cells and tumors. An exemplary study in this direction was recently published by Yang and colleagues, who developed HA-targeted PEGylated poly(ethylene imine) NPs loaded with Pgp-siRNA and PTX [13]. They showed that transfection of resistant SKOV-3TR cells with these NPs decreased Pgp expression levels, while no significant changes in Pgp expression were observed in cells transfected with untargeted NPs. The in vivo efficacy of this formulation was also tested, in mice bearing SKOV-3TR xenografts, demonstrating that tumor volumes were significantly reduced upon treatment with the HA-targeted formulation and validating the potential of CD44 targeting as a means to more efficiently address MDR.

MDR cells may also manipulate their microenvironment for enhanced progression and survival. Indeed, it was reported that multiple MDR cells, such as MCF-7/AdrR, KBv-1 and A2780Dx5, overexpress the extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer EMMPRIN, which stimulates the expression of the matrix metalloproteinases MMP1, MMP2 and MMP9 [14]. These findings suggest that MDR cells actively remodel the ECM via MMP expression. MMP-mediated ECM remodeling is disadvantageous in relation to infiltration and metastasis, but it may actually be positive for drug delivery, facilitating the penetration of drugs and drug delivery systems deep into the tumor interstitium. In addition, drug delivery systems can be made MMP-responsive. Several studies already employed protease-sensitive linkers which allow for controlled MMP-mediated drug release. In one such study, combinatorial delivery of cisplatin and bortezomib was achieved by using mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) which were capped via linkers which can be cleaved by MMP9 [15]. The MSN were tested in lung cancer cells and in 3D ex vivo human lung tissue cultures, and the results indicated a significant level of cell death only in the presence of MMP9. To show the selectivity of their system, the authors applied the MMP9-responsive MSN to tumor-containing and tumor-free sections in the 3D lung tissue model, and found apoptosis induction only in tumorous regions. For stably capped MSN formulations which lack the MMP-cleavable linkers, no apoptosis induction was observed, neither in tumors, nor in healthy lung tissue. This study shows that NPs which respond to microenvironmental MDR triggers, such as enhanced MMP expression and activity, can be employed to promote drug release only in target tissues.

Expert Opinion

MDR is characterized by multiple cellular and microenvironmental alterations. A thorough investigation of these changes, and of interplay between resistant cancer cells and their microenvironment, is necessary to better understand MDR. This improved understanding will provide a framework for the development of novel drugs and drug delivery systems for more efficiently targeting and treating MDR malignancies.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD: 57048249), by the EU 7th Framework Programme (Marie Curie grant: 642028) and by the European Research Council (ERC-StG: NeoNaNo).

References

- 1.Kunjachan S, Rychlik B, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Multidrug resistance: physiological principles and nanomedical solutions. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65(13):1852–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correia AL, Bissell MJ. The tumor microenvironment is a dominant force in multidrug resistance. Drug resistance updates. 2012;15(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kievit FM, Wang FY, Fang C, Mok H, Wang K, Silber JR, Ellenbogen RG, Zhang M. Doxorubicin loaded iron oxide nanoparticles overcome multidrug resistance in cancer in vitro. Journal of controlled release. 2011;152(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Pluronic block copolymers: evolution of drug delivery concept from inert nanocarriers to biological response modifiers. Journal of controlled release. 2008;130(2):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Zhang W, Gu J, Ren Q, Fan Z, Zhong W, Fang X, Sha X. Enhanced antitumor efficacy by methotrexate conjugated Pluronic mixed micelles against KBv multidrug resistant cancer. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2013;452(1):421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel NR, Rathi A, Mongayt D, Torchilin VP. Reversal of multidrug resistance by co-delivery of tariquidar (XR9576) and paclitaxel using long-circulating liposomes. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2011;416(1):296–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng H, Mai WX, Zhang H, Xue M, Xia T, Lin S, Wang X, Zhao Y, Ji Z, Zink JI, Nel AE. Codelivery of an optimal drug/siRNA combination using mesoporous silica nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance in breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. ACS nano. 2013;7(2):994–1005. doi: 10.1021/nn3044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comerford KM, Wallace TJ, Karhausen J, Louis NA, Montalto MC, Colgan SP. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent regulation of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene. Cancer research. 2002;62(12):3387–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: targets for anti-angiogenesis and normalization. Microvascular research. 2007;74(2):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batchelor TT, Gerstner ER, Emblem KE, Duda DG, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Snuderl M, Ancukiewicz M, Polaskova P, Pinho MC, Jennings D, Plotkin SR. Improved tumor oxygenation and survival in glioblastoma patients who show increased blood perfusion after cediranib and chemoradiation. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2013;110(47):19059–19064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318022110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damiano JS, Cress AE, Hazlehurst LA, Shtil AA, Dalton WS. Cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR): role of integrins and resistance to apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines. Blood. 1999;93(5):1658–1667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong XB, Lavasanifar A. Traceable multifunctional micellar nanocarriers for cancer-targeted co-delivery of MDR-1 siRNA and doxorubicin. ACS nano. 2011;5(6):5202–5213. doi: 10.1021/nn2013707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Singh A, Choy E, Hornicek FJ, Amiji MM, Duan Z. MDR1 siRNA loaded hyaluronic acid-based CD44 targeted nanoparticle systems circumvent paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer. Scientific reports. 2015;5:8509. doi: 10.1038/srep08509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JM, Xu Z, Wu H, Zhu H, Wu X, Hait WN. Overexpression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in multidrug resistant cancer cells1 1 US Public Health Service National Cancer Institute CA 66077 and CA 72720. Note: JM. Yang and Z. Xu contributed equally to this study. Molecular cancer research. 2003;1(6):420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rijt SH, Bölükbas DA, Argyo C, Datz S, Lindner M, Eickelberg O, Königshoff M, Bein T, Meiners S. Protease-mediated release of chemotherapeutics from mesoporous silica nanoparticles to ex vivo human and mouse lung tumors. ACS nano. 2015;9(3):2377–2389. doi: 10.1021/nn5070343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]