Abstract

New developments in accelerating wound healing can have immense beneficial socioeconomic impact. The wound healing process is a highly orchestrated series of mechanisms where a multitude of cells and biological cascades are involved. The skin battery and current of injury mechanisms have become topics of interest for their influence in chronic wounds. Electrostimulation therapy of wounds has shown to be a promising treatment option with no-device-related adverse effects. This review presents an overview of the understanding and use of applied electrical current in various aspects of wound healing. Rapid clinical translation of the evolving understanding of biomolecular mechanisms underlying the effects of electrical simulation on wound healing would positively impact upon enhancing patient’s quality of life.

Keywords: electrotherapy, wound healing, infection, bioelectric current, exogenous current, bioelectric medicine, electrical stimulation, chronic wound, acute wound

Introduction

Efficacious wound healing is still a clinical challenge and the complications associated with impairment in wound healing carry a great financial burden as well as a negative impact on patient lifestyle. Among chronic wounds, the highest prevalence lays in the venous leg ulcer, diabetic foot/leg wound (DFU), and pressure ulcer categories. Complex chronic wounds, such as diabetic ulcers, have a major long-term impact on the morbidity, mortality, and quality of patient’s life. In 2010, the NHS in England has spent around £650 million on foot ulcer management and amputation, which represent ~0.5% of its budget.1 In the USA, 33% of the $116 billion total health care spend on diabetes is on the management of foot ulceration.2 In Europe, cost of wound management accounts for 2%–4% of the health care budgets.3 Furthermore, Diabetes UK estimates that by 2030, nearly 552 million people worldwide will develop diabetes.4 Estimates indicate that 15% of all diabetes patients will develop DFUs and of that 84% leading to lower leg amputations.

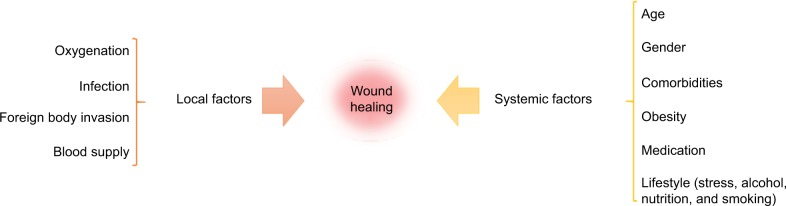

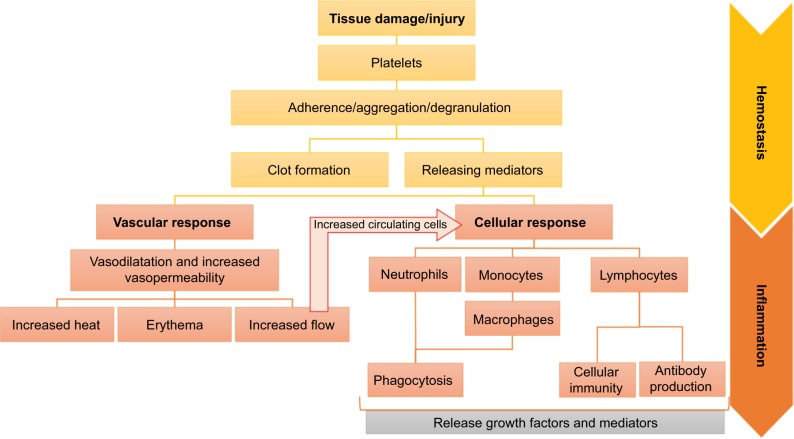

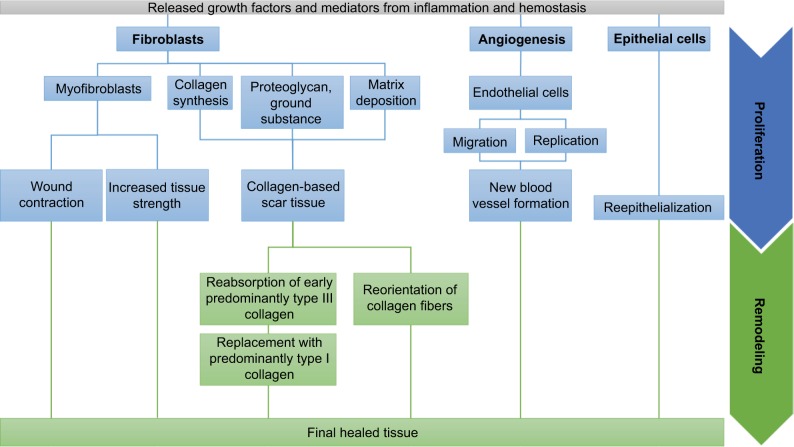

The wound healing process is influenced by several local and systemic factors5,6 (Figure 1), and is complex with a multitude of biomolecular pathways, but comprises four distinct yet interrelated phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (Figures 2 and 3). The human epidermis exhibits a natural endogenous “battery” that generates a small electric current when wounded.7,8 Healing is arrested when the flow of current is disturbed or when the current flow is stopped during prolonged opening. Different treatment strategies exist for the management of chronic wounds; some are invasive, such as wound debridement and skin substitute therapy, while others are noninvasive, such as compression bandaging, wound dressing, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, negative pressure therapy, ultrasound, and electrostimulation therapy (EST). EST is relatively cost-effective, safe, painless, and easy to use. EST mimics the natural current of injury and jump starts or accelerate the healing process.

Figure 1.

Local and systemic factors that influence wound healing

Figure 2.

Hemostasis and inflammation phases of wound healing.

Notes: After an injury, the hemostasis (yellow) leads to cessation of bleeding. The platelets adhere to form a clot and release mediators to induce additional platelet aggregation and mediate the phases of the healing process. The released mediators trigger the inflammatory phase (orange), divided into a vascular and a cellular response. Neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes are cleaning the wound while the surrounding vascular system dilates, allowing more blood volume and circulating cells to be recruited. Neutrophils and macrophages migrate toward the wound in order to clear the area of debris, bacteria, and dead tissues, also known as phagocytosis. In addition to providing cellular immunity and antibody production, lymphocytes act as mediators within the wound environment through the secretion of cytokines and direct cell-to-cell contact.

Figure 3.

Proliferation and remodeling phases of wound healing.

Notes: The proliferation phase (blue) is a reconstruction step, where cells are working to form granulation tissues and restore a functional skin. Several events are conducted simultaneously: angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, wound contraction, collagen deposition, and reepithelialization. Activated endothelial cells create new blood vessels by proliferating and migrating toward the source of the angiogenesis stimulus. The epidermal cells proliferate and migrate at the wound edge to initiate wound recovery. Stimulated fibroblasts synthesize collagen, ground substance, and provisional matrix to create a collagen-based scar tissue. Some of them also differentiate into myofibroblast that contracts and induces mechanical stress inside the wound. During the remodeling phase (green), the matrix is turned over and the wound undergoes more contraction by the myofibroblasts. Collagen is also reorganized and reoriented.

The effect of electrical stimulation (ES) has been tested in vitro on different types of cells involved in wound healing, such as macrophages,9 fibroblasts,10–14 epidermal cells,15–20 bacteria,21–23 and endothelial cells24–26 that have demonstrated changes in cell migration, proliferation, and orientation, increase in proteins and DNA synthesis, and antibacterial effects. When applied on in vivo models27–40 and clinical stud ies,41–61 EST has shown positive effects on wound closure and healing rate. Other outcomes, such as increased angiogenic response, wound contraction, and antibacterial effects have also been reported. However, there is a considerable variation in study design, outcome measures, ES parameters, type of current, type of wound, and treatment duration, and dose, thus presenting further questions on the most optimal approach for the treatment of cutaneous wound healing is crucial. This review presents an overview of the state-of-the-art medical technology applications and technologies associated with “smart” materials that can be potentially exploited to mimic the current of injury for wound healing and skin regeneration, with reports on the therapeutic evidences of their present use in clinical practice.

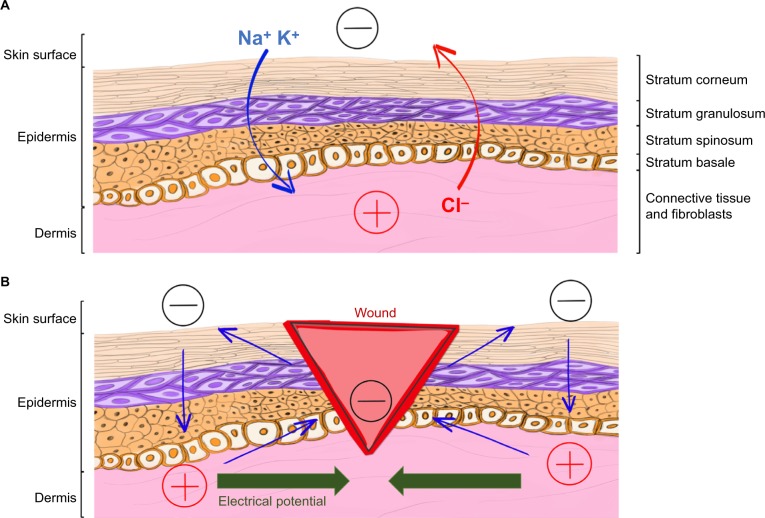

Endogenous bioelectric current

It is known that the human body possesses an endogenous bioelectric system that produces natural electrochemical signals in different areas, such as the brain, skin, muscles, heart, and bones. In physiological solution, there are no free electrons to carry the current. Thus, it is carried by charged ions. Across the tissues, asymmetric ionic flows generate electrical potentials (Figure 4A). A transepithelial electric potential, named skin battery, is generated by the movement of ions through Na+/K+ ATPase pumps of the epidermis.20

Figure 4.

Cutaneous endogenous bioelectric current before and after injury.

Notes: Unbroken skin layers of the epidermis and dermis (A) maintain the skin battery across the body through ionic movement of Na+, K+, and Cl−, generating a polarity with positive (+) and negative (−) poles. When wounded (B), the current flows out of the wound (blue), generating an endogenous electrical potential (green) with the negative pole (−) in the wound center and the positive pole away from the wound (+). These changes can be viewed in Video S1. Data from Zhao et al.20

Current of injury, which is essential for normal wound healing (Figure 4B and Video S1), is generated during skin injury. This electrical leak, which is a long-lasting lateral electrical potential, short-circuits the skin battery. Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl− ions are the main components of this electrical current.62 The current of injury, measurable 2–3 mm around the wound and from around 10 to 60 mV,8 creates an electrical potential directed toward the wound with the negative pole at the wound center and the positive at the edge20,63 and attracts cells toward the injury. The current is sustained in a moist environment and shuts off when a wound dries out.64 The link between ionic flux, current of injury, and healing rate has been made in 1983. Increase in Cl− and Na+ influx with AgNO3 in wounded corneal epithelium of rats induced a significant augmentation of the current of injury, resulting in enhanced wound healing. However, rat corneal wounds with furosemide (a component that inhibits Cl− efflux) exhibited a significant diminution of the current of injury, resulting in impaired corneal wounds.

Effects of exogenous electric current on wound healing

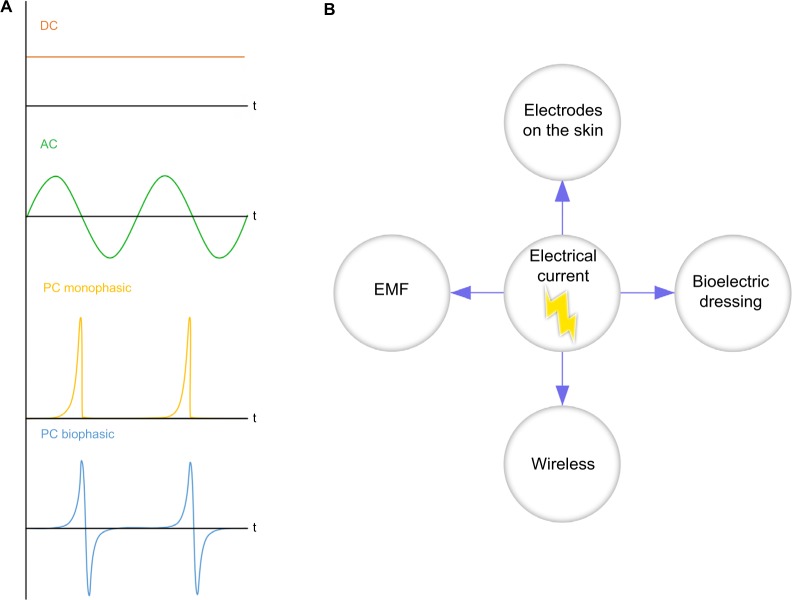

ES is used in several disciplines, such as electroanalgesia for chronic pain control, pacemakers to regulate heartbeat, cochlear stimulation to aid hearing, functional ES to restore mobility in people with paralyzed limb(s), in addition to enhance wound healing.65 In wound healing, four main therapeutic approaches have been identified: direct current (DC), alternative current (AC), pulsed current (PC), and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS; Figure 5A). In each therapeutic approach, different parameters, such as the voltage, duration, frequency, phase, mode, and type of pulse, can be controlled. Depending on the protocol, the impulse amplitude is either preset by the operator at the maximum value according to the patient’s sensitivity threshold of the stimulated tissue or can be changed by the patient during the treatment according to personal sensitivity. DC is continuous and simple. If DC is applied for a too long duration and amplitude, DC can cause tissue irritation and damage. On a porcine wound, AC and DC both reduced healing time.37 However, DC seemed to be more efficient than AC to reduce the wound area, and AC seemed to be more efficient than DC to reduce the wound volume.

Figure 5.

Types of electrical current and their different methods of application.

Notes: Four main types of current have been identified (A). Direct current (orange) is a continuous, unidirectional flow of charged particles that has no pulses and no waveform. DC is characterized by an amplitude and a duration. Its polarity remains constant during the stimulation. Alternative current (green) is a continuous bidirectional flow of charged particles in which a change in direction of flow occurs. AC stimulation is characterized by an amplitude, duration, and frequency. Pulsed current is a brief unidirectional or bidirectional flow of charged particles composed of short pulses separated by a longer off period of no current flow. PC stimulation is characterized by a frequency, duration, and pulse. The pulse is defined by a waveform, amplitude, and duration. The waveform can be monophasic (yellow), with constant polarity, or biphasic (blue), with alternating polarity. Electrical current can stimulate wound healing through different type of applications (B): electrodes on the skin, bioelectric dressing, wireless current stimulation, and EMF.

Abbreviations: EMF, electromagnetic field; DC, direct current; AC, alternative current; PC, pulsed current.

PC is one of the most documented EST. In clinical trials, low voltage, high voltage, degenerative waveform, and short voltage PC (SVPC) have shown positive effects when used on diabetic and chronic ulcers.43–51,55,61 One randomly controlled clinical trial (RCT) has tested different durations of stimulation on ulcer patients and showed that 60 and 120 min of stimulation significantly reduced the wound surface area compared to 45 min.42 SVPC devices, such as Aptiva Ballet (Lorenz Therapy system) or Naturepulse (Globe Microsystems), generate short voltage impulse patterns. Each impulse is characterized by a specific sharp spike. During the stimulation, frequency, pulse amplitude, and pulse width vary automatically. SVPC increases the circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the blood during the stimulation and induces nitric oxide formation the day after treatment.66 Moreover, SVPC has shown enhanced wound area reduction in the treatment of chronic, venous, and diabetic ulcers, in four RCTs,50,53,54,56 but the short period of the studies has not allowed to evaluate the wound healing rate. One RCT53 has used SVPC on chronic leg ulcers with an “until-healed” treatment duration. This duration of treatment allowed to evaluate the wound closure and reported that SVPC enhanced wound closure. TENS is a low- or high-frequency pulsed electrical current that stimulates the peripheral nerves. This stimulation is used in clinical practice for the relief of chronic and acute pain. It is believed that stimulation of the peripheral nerves increases blood flow and could help healing. TENS locally increases the blood flow and VEGF level in healthy and diabetic patients.67–70 However, no study has tested the effect of TENS on wound healing.

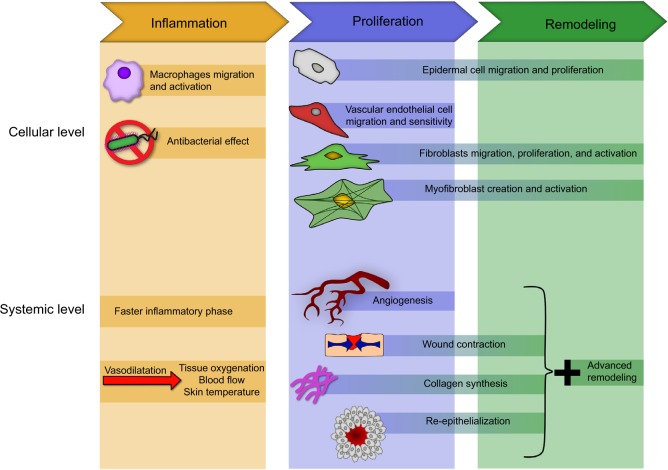

Figure 5B shows the summary of different methods of application. Electrodes can be placed next to or directly on the cutaneous wound. A portable and independent dressing can also recover the wound and deliver a small current.71 Electromagnetic field and wireless microcurrent stimulation can allow the user to deliver a broad stimulation under the skin without touching it directly, and both have shown promising results on chronic wounds.60,71,72 The optimal approach and relevant parameters for a given condition is yet to be determined. However, studies at the cellular and systemic level have already shown that EST affects several cells and events involved in wound healing (Figure 6). During inflammation, ES induces a faster inflammatory response39 and an increased vascular vasodilatation73 that increases tissue oxygenation,37 blood flow,37,58,59,69 and skin temperature.59 During the proliferation phase, ES generates increased angiogenesis,30,36,57,59 collagen matrix formation,36–38 wound contraction,29,57 and reepithelialization.57,60 Finally, during the remodeling phase, increased cellular activity produces an advanced remodeling57 at a systemic level. RCT and in vivo trials have demonstrated the positive effects of EST on wounds (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 6.

Reported effects of ES on wound healing at the cellular and systemic level during inflammation (yellow), proliferation (blue), and remodeling (green).

Notes: During inflammation, ES increases macrophages migration and activity and decreases bacterial proliferation at the cellular level. At a systemic level, it induces a faster inflammatory response and an increased vascular vasodilatation that increases tissue oxygenation, blood flow, and skin temperature. During the proliferation phase, ES increase the migratory response and activity level of epidermal cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts. At the systemic level, it generates increased angiogenesis, collagen matrix formation, wound contraction, and reepithelialization. Finally, during the remodeling phase, the activity of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts is enhanced at a cellular level and produces an advanced remodeling at a systemic level.

Abbreviation: ES, electrical stimulation.

Table 1.

Animal in vivo studies testing the effects of electrical stimulation on wound healing

| Type of ES | Type of wound | Animal | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC35 | Incision wound | Pig | Increased wound closure, increase of fibroblasts collagen, no difference in microvessel number |

| DC39 | Incision wound | Rat | Decrease of PMN and macrophages, increase of fibroblasts |

| DC or AC37 | Incision wound | Pig | Reduced healing time and increased perfusion, DC reduced wound area more rapidly, AC reduced the wound volume more rapidly |

| DC or PC28 | Incision wound | Rat | Increased biomechanical properties, collagen density, and wound closure |

| PC31 | Incision wound | Mice | Acceleration of healing in 0.9–1.9 kV/m and suppression in 10 kV/m |

| PC40 | Diabetic excision wound | Mice | Altered collagen deposition and cell number |

| PC35 | Incision wound | Pig | Greater and faster wound surface area |

| PC29 | Incision wound | Rabbit | Increased number of fibroblasts and higher tensile strength |

| PC30 | Incision wound | Rat | Increase of blood vessels and fibroblasts |

| PC33 | Diabetic incision wound | Rat | Increase wound healing, upregulation of collagen I and TGF |

| PC36 | Ischemic model | Rabbit | Increase of VEGF and collagen IV and activity of collagen I and V |

| TENS34 | Skin flap | Rat | Increased wound closure |

| TENS32 | Incision wounds | Rats | Proinflammatory cytokines reduction, and increased wound closure, reepithelialization, and granulation tissue formation |

Abbreviations: AC, alternative current; DC, direct current; ES, electrical stimulation; PC, pulsed current; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; TGF, transforming growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table 2.

Clinical trial studies about EST on wound healing

| Type of ES | Equipment | Design | Blinding | Type of wound | Duration (days) | Structure | Patients (n)

|

ES parameters | ES effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Tx | CON | |||||||||

| DC60 | WMCS device (Wetling, Friedensborg, Denmark) | Control | Not reported | Mixed ulcers | 56 | 2–3 times weekly, 45–60 min | 47 | 47 | NA | 1.5 µA | WAR |

| DC41 | Not reported Stimulation (Henley International, Houston, TX, USA) | RCT | Double-blind placebo | Pressure ulcers | 56 | 20 min, 3 times daily, then 2 times daily after 14 days | 63 | 35 | 28 | Not reported | Wound closure and WAR |

| AC52 | Electrical Nerve | RCT | Single-blind | Diabetic venous ulcers | 84 | 20 min, 2 times per day | 64 | 24 | 27 | 80 Hz, 1 ms pulse width | Wound closure and WAR |

| PC51 | Biopac MP100 (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA, USA) | RCT reported | Not | Chronic wounds of diabetic and nondiabetic | 28 | 3 times per week | 20 | 20 | 0 | 5 V, pulse width 200 µs, 30 Hz, 20 mA | Higher WAR in diabetics than in nondiabetics |

| LVPC43 | Experimental direct current generator | Retrospective | Not reported | Mixed ulcers | 35 | 2 h, 5 days a week | 30 | 15 | 15 | 300–500 µA or 500–700 µA | WAR |

| LVPC61 | MEMS CS 600 (Harbor Medical Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) | Placebo | Double-blind | Pressure ulcers | 56 | 3 times weekly | 78 | 41 | 30 | 300–600 µA, 0.8 pps | Wound closure |

| HVPC44 | Vara/pulse stimulator (Staodynamics Inc, Longmont, CO, USA) | RCT | Double-blind | Mixed ulcers | 28 | 30 min, 2 times daily | 47 | 26 | 24 | 29.2 V, maximum 29.2 µA, 64–128 pps | WAR |

| HVPC45 | Ionoson (Physiomed, Essen, Germany) | RCT | Not reported | Pressure ulcers | 42 | 50 min, 5 days a week | 50 | 26 | 24 | 100 V; 100 µs; 100 Hz) | WAR |

| HVPC46 | Ionoson (Physiomed, Essen, Germany) | RCT | Not reported | Venous leg ulcers | 42 week | 50 min, 6 days a | 76 | 62 | 14 | 100 V, 100 pps, monophasic | WAR |

| HVPC47 | Intelect 500 HVPC stimulator (Chattanooga Corp, Chattanooga, TN, USA) | RCT | Single-blind placebo | Pressure ulcers | 20 | 1 h daily | 17 | 8 | 9 | 100 pps, 200 V, 500 µA | WAR |

| HVPC48 | Micro Z (Prizm Medical Inc, Duluth, GA, USA) | RCT | Single-blind | Pressure ulcers | 90 | Around 3 h daily | 34 | 16 | 18 | 50 µs pulse duration, 50–150 V, 20 min at 100 Hz, 20 min at 10 Hz, and 20 min off cycle | Wound closure and WAR |

| HVPC49 | EGS Model 300 (Electro-Med Health Industries, North Miami, FL, USA) | RCT | Double-blind | Mixed ulcers | 28 | 45 min, 3 times a week | 27 | 14 | 13 | 100 µs, 150 V, 100 Hz | WAR |

| HVPC55 | Micro-Z (Prizm Medical Inc, Duluth, GA, USA) | RCT | Double-blind | Diabetic foot ulcers | 84 | 8 h daily | 40 | 20 | 20 | 50 V, 100 µs, 80 pps for 10 min then 8 pps for 10 min, and 40 min standby cycles | Wound closure and WAR |

| SVPC50 | Aptiva Ballet (Lorenz Terapy System, Lorenz Biotech, Medolla, Italy) | RCT | Not reported | Mixed ulcers | 21 | 40 min daily, 5 days a week | 35 | 20 | 15 | 300 V, 1000 Hz, 10–40 µs, 100–170 µA | WAR |

| SVPC53 | Aptiva Ballet (Lorenz Therapy System, Lorenz Biotech, Medolla, Italy) | RCT | None | Chronic leg ulcers | Until healed | 3 per week for 4 weeks, followed by 2 weeks rest | 60 | 30 | 30 | 0–300 V, 1–1000 Hz, 10–40 µs, 100–170 µA | Wound closure and reduction of pain |

| SVPC54 | Aptiva Ballet (Lorenz Therapy System, Lorenz Biotech, Medolla, Italy) | RCT | None | Diabetic foot ulcers | 30 | 30 min, every 2 days | 30 | 16 | 14 | 0–300 V, 1–1000 Hz, 10–40 µs, 100–170 µA | WAR |

| SVPC56 | Aptiva Ballet (Lorenz Therapy System, Lorenz Biotech, Medolla, Italy) | RCT | Not reported | Venous ulcers | 21 | 25 min, 5 days a week | 20 | 10 | 10 | 0–300 V, 1–1000 Hz, 10–40 µs, 100–170 µA | WAR |

| SVPC59 | Fenzian system (Fenzian Ltd, Hungerford, UK) | RCT | None | Healthy volunteers, acute wounds | 90 | 4 times during the second week | 40 | 40 treatment arms | 40 control arms | 0.004 mA, 20–80 V, 60 Hz, degenerative waves | Increase angiogenic response |

| SVPC58 | Fenzian system (Fenzian Ltd, Hungerford, UK) | Controlled study | None | Healthy volunteers, acute wounds | 90 | 4 times during the second week | 20 | 20 treatment arms | 20 control arms | 0.004 mA, 20–80 V, 60 Hz, degenerative waves | Increase blood flow and hemoglobin levels |

Abbreviations: CON, control; DC, direct current; ES, electrical stimulation; EST, electrostimulation therapy; HVPC, high-voltage pulsed current; LVPC, low-voltage pulsed current; SVPC, short-voltage pulsed current; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Tx, treatment; WAR, wound area reduction.

ES cellular and molecular mechanisms

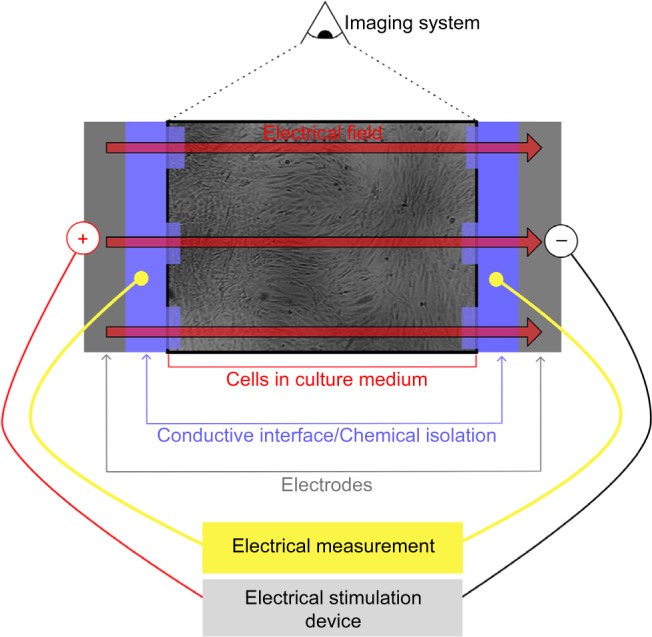

The mechanisms by which cells sense and respond to ES remain relatively unclear, it is believed that the extracellular electrical potential gradient generates an asymmetric signal between the two poles of the cells parallel to the electrical field lines. The cell membrane possesses an electrical potential that averages 70 mV and variation of this potential influences the cell’s general activity. If the membrane is electrically quiescent, the cell downregulates and its functional capacity diminishes. Conversely, with increased levels of electrical activity, upregulation occurs and the general cell activity level increases.26 It is believed that by using ES, we can influence the electrical activity of the cell membrane and induce specific cellular responses. To evaluate how cells respond when exposed to an electrical current, experiments have been performed in electrotaxis chambers74 (Figure 7) and specifically designed culture plates.75,76 At the cellular level, EC may affect the ion channels and/or the membrane receptors, which constantly monitors the cell response to the microenvironment. Under an EC, both ion channels and transport proteins are activated and reorganized across the cell, independently of the external chemical gradient and ionic flow, to contribute toward intracellular polarization and cellular response.77 Intracellular pathways, such as phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase,20,78,79 and elements, such as golgi apparatus,10,19 seem to play a role in the galvanotaxis response.

Figure 7.

This experimental setup has been reported by Farina et al70 and has been used in several other articles.

Notes: The cell culture (blue) is done within an electrotactic chamber that isolates it from the outside (usually a modified well plate). The electrodes from the ES device are stimulating the cells through a conductive interface (blue) to the cell culture to avoid any electrochemical products in the cell culture. The electricity delivered is followed with an electrical measurement system (yellow), such as an oscilloscope. Finally, the evolution of the cells is tracked with a microscope (green) and the images are stored in a computer. Data from Song et al.74 Abbreviation: ES, electrical stimulation.

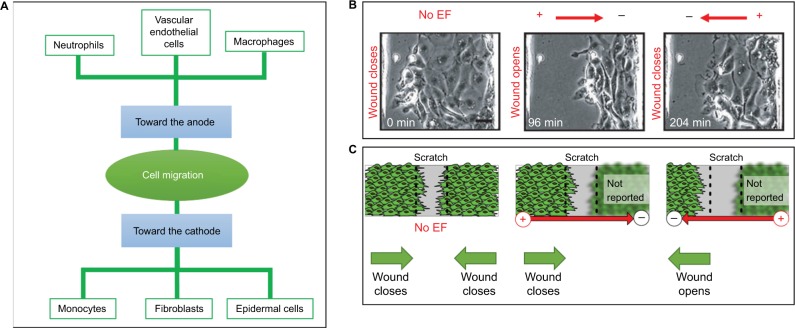

Individually, each cell type exhibits specific behaviors under ES and no ES displays a significant reduction of cell viability or cytotoxic effect. First, the polarity of the EC directs the cell migration and splits them in two groups, the one migrating toward the anode and the one migrating toward the cathode (Figure 8A). In a monolayer organization, cells also exhibit polarity-dependent behaviors19,20 (Figure 8B). In a scratch assay, a monolayer of corneal epithelium cells moved into the wounds in a coordinated manner without EC and faster with one that possessed the same polarity as the natural endogenous EC. Reversely, when applied opposite to the normal healing direction, the EC directed the cells at the wound edge, away from the wound, opening the wound. The same effect has been reported with a monolayer of fibroblasts19 (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

The polarity of the electrical current is a key feature in wound healing.

Notes: In isolated cell culture, neutrophils, vascular endothelial cells, and macrophages migrate toward the anode, and monocytes, fibroblasts, and epidermal cells toward the cathode (A). The polarity of the applied electrical current directly affects the direction of the cell migration on a scratch assay with a monolayer of corneal epithelial cells (B) and fibroblasts (C). Figure B adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature. Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, et al. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. 2006;442(7101):457–460. Copyright 2006. Available from http://www.nature.com/.20 Figure C data from Pu and Zhao.19

Furthermore, other outcomes have been used in vitro to measure the cell activity under EC. Under EC, fibroblasts proliferate, elongate, and reorient in vitro.10–12,14 Electrically stimulated fibroblasts seem to have a higher contractile behavior and higher fibroblast to myofibroblast transdifferentiation.11 DC, AC, and PC have exhibited highly differential effects on fibroblasts in an in vitro study, where at high intensity and frequencies, the PC maximally downregulates collagen I and have a lower cytotoxic effect than AC and DC.13 At the wound site, enhanced fibroblast activities with DC, PC, and HVPC have also been reported in vivo, resulting in an increased fibroblast number,29,39 collagen synthesis,13,29,33,36,38 myofibroblast creation, and tensile strength.29 HVPC on diabetic rats has shown accelerated wound healing and restoration of the expression levels of collagen I and transforming growth factor, suggesting reactivation of the fibroblast activities.33 Under ES, vascular endothelial cells have also reported changes in cell elongation and orientation24–26 and upregulation of the levels of VEGF and IL-8 receptors.24 Recent studies have also tested the effects of ES on macrophages that exhibit enhanced phagocytic activity9 and platelets that display growth factors releases.80

Severe bacterial invasion can arrest the healing process and lead to chronic wound. Traditionally, systemic antibiotic treatments are used to treat severe infection. However, overuse of antibiotics can increase the bacterial resistance and lead to inefficient antibiotics. It is believed that ES may impose a bacteriostatic effect on microbes and bacteria that commonly colonize or infect wounds.21 Studies have shown that HVPC and DC kill or inhibit the proliferation of common wound pathogens,22,23 such as Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. DC, HVPC, and LVPC have been tested in vitro on S. aureus.23 Apparently, HVPC and DC treatments have a significant inhibitory effect compared to LVPC. Moreover, no difference in bacterial growth inhibition was found when varying polarity and time of ES. At present, we are unclear as to why the ES seems to induce an antibacterial effect by direct or indirect mechanisms. The electrical current may directly disrupt the bacterial membrane or block its proliferation. Indirectly, the electrical current may induce a change of pH or temperature within the wound, a production of electrolysis products, or an increased migration of macrophages and leukocytes, resulting in an antibacterial effect.

Angiogenesis: friend or foe?

Angiogenesis is a key event in wound healing. While insufficient angiogenesis can lead to chronic wound formation, aggressive angiogenesis can lead to abnormal scarring. Thus, spatiotemporal control of EST to enhance angiogenesis is crucial. Several studies on animal models and clinical trials have shown that ES increases the level of VEGF and the number of blood vessels in the wound.30,58,59,66,73 Higher levels of VEGF linked to enhancing angiogenesis and advanced healing have been reported in the stimulated arm of each patient. VEGF is the most used angiogenic marker as it presents all the characteristics of a specific angiogenic factor81 and is predominantly produced by macrophages, platelets, endothelial cells, epidermal cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and mast cells.82 Indirectly, increased angiogenesis can facilitate local tissue oxygenation.

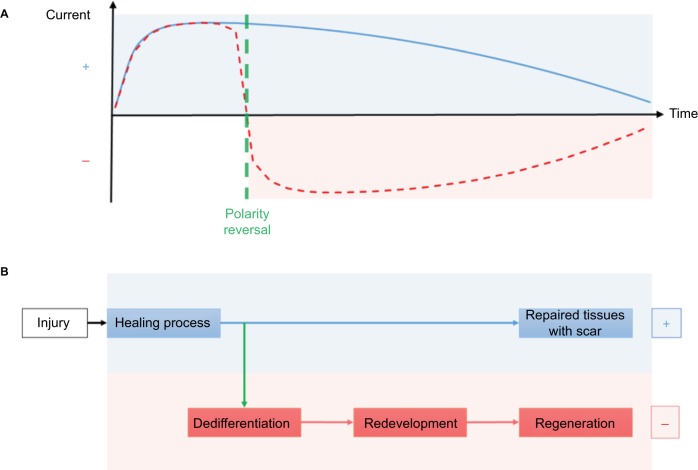

Electrotherapy: the path to regeneration beyond repair?

Salamanders and newts exhibit impressive regenerative ability that is divided into three phases: wound healing, dedifferentiation, and redevelopment, where they can regrow a whole limb. Humans are limited in repairing the localized damaged area. Both human repair and regenerative processes are regulated by ionic flows and endogenous electrical current. However, the evolution of the endogenous electrical current is distinctly different in regenerating and nonregenerating species (Figure 9). In nonregenerative species, the positive current decreases simultaneously as the wound heals. However, in regenerative species, the initial positive polarity of the injured tissue sharply reverses to a high negative polarity that gradually reduces as the damaged area regenerates.83 Particularly, the regeneration of the limb seems to be stopped if the polarity of the electrical current does not reverse. Recently, an in vivo experimentation on 90 tendons of rabbits has linked variation in the healing response with the polarity of the exogenous ES.27 Even if both cathodal and anodal stimulation exhibited accelerated healing rate, cathodal (negative) ES showed more significant improvements than anodal (positive) ES in the first 3 weeks, while anodal ES showed more significant improvement after 3 weeks. Cathodal stimulation may promote and attract macrophages in the early stage of wound healing, resulting in a faster inflammatory phase, and anodal stimulation may promote and attract fibroblasts in the late stage of wound healing, resulting in advanced remodeling phase. Recognition of the ES polarity dependence on the stage of the wound could lead to better healing response and less scar formation.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the current of injury in regenerative and nonregenerative species after injury (A). In nonregenerative species (blue), the current stays positive and gradually reduces as the wound heals. In regenerative species (red), a polarity reversal (green) occurs while healing. The negative current gradually reduces as the damaged area regenerates. After an injury (B), both regenerative and nonregenerative species exhibit a healing process. After the polarity reversal of the regenerative species, a dedifferentiation, where cells lose their specialized characteristics and migrate, occurs. Then the limb regrows during the redevelopment and leads to a complete regeneration, where nonregenerative species have maintained their positive current and repaired tissues with a scar.

Smart materials, technology, and ES

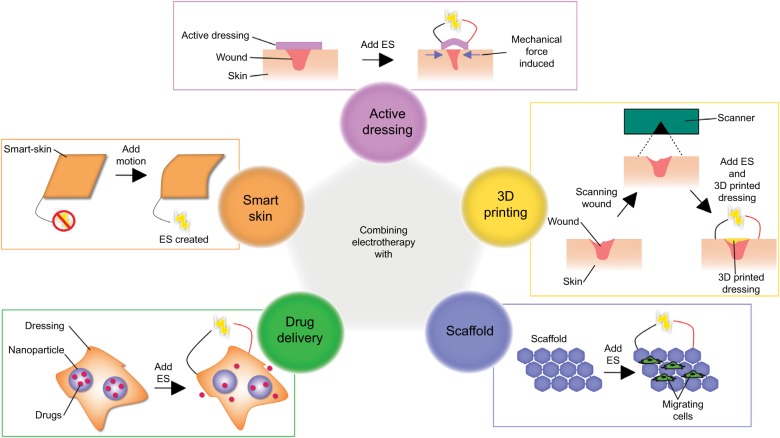

Electrotherapy could be combined with the state-of-the-art technologies for potentially superior therapeutic effects in wound healing and skin regeneration (Figure 10). For instance, researchers have set up human skin-based triboelectric nanogenerators84 and smart skins85 that can harvest the biomechanical energy to produce renewable electricity. Such technologies could power a bioelectric dressing that would stimulate the wound. New dressings made of conductive and inherently antibacterial materials, such as electroactive doped polyurethane/siloxane membrane,86 can work simultaneously with electrotherapy by restoring the physiological homeosta-sis at the wound site and biomimicking the current of injury. Moreover, electrically controlled drug delivery could be achieved within a dressing or scaffold by using electrically responsive hydrogels87,88 or graphene oxide nanocomposite films89 filled with nanoparticle system containing the drug. With this approach, drug release could be modulated by the endogenous or exogenous electrical current. Using a scaffold, such as collagen/gold nanoparticle scaffolds90 or injectable microporous gel scaffolds,91 could provide a biodegradable structure and accelerate cell migration to the wound site, following which an ES can enhance the cellular activity within the scaffold. Specific materials properties can be combined with EST for better aesthetics of the wound during the treatment, by creating a layer on the skin to disguise or “hide” the wound.92 3D printing is a relatively novel method that enables bespoke therapy and offers an opportunity to 3D print skin scaffolds using the patient’s own cells93 as well as the ability to make bespoke patches.94 Shape memory polymer composites,95 which have properties similar to uninjured skin, are of great interest to generate electricity-dependent mechanical and thermal stresses on the wound. These stresses would depend on the intensity of the current of injury, and thus, would evolve during each phase of the healing process.

Figure 10.

Electrotherapy can be combined with state of the art technology, such as active dressings, 3D printing, scaffold, drug delivery, or smart skin.

Abbreviation: ES, electrical stimulation.

Role of magnetic field

Furthermore, significant beneficial effects have been reported with the use of magnetic field in pain management, bone fracture, and wound healing.96 It is particularly intriguing when we know that magnetic and electric forces are linked by the Maxwell’s equations. Every electric field generates a magnetic field in the surrounding environment and vice versa. Scientists refer to the use of electric and magnetic fields in medicine as the electromagnetic field therapy.96 In vitro, magnetic field seems to elicit changes in cells of the immune systems through Ca2+ signaling, including upregu-lated cytokine synthesis and increased cell proliferation. The electromagnetic field generates an ionic flow under the skin that is similar to the one seen in electrotherapy. However, more studies are needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the response of biological tissue to both electric and magnetic fields.

Conclusion and the future

Electrotherapy and associated smart materials and technologies promise to improve chronic wound healing strategies and can be potentially established as a clinically robust and commercially viable system for wound healing that will make a great impact in global health care and economy. However, there are considerable variations in parameters, modes, dosing, and duration of treatment that lead to complications in comparison of the data with a need for more well-designed clinical trials.

The healing process undergoes different stages and each stage involves a different and interlinked set of cellular events. More studies are warranted to delineate their mechanism and the influence of ES on them. Recognizing the type of current and the corresponding cellular activity, which it most influences may help to present personalized treatment to specific types of wounds. Electrotherapy devices at the current age of digital health care, together with developments in responsive smart materials and technologies, could enable continuous monitoring of the status of patient’s wound, allowing instant feedback responses, thus allowing the health care provider to choose with ease, preselected parameters that would optimally accelerate wound healing. These possible innovations could have an impact on other related diseases, such as Raynaud’s disease, necrotizing fasciitis, or cosmetic concerns, such as chickenpox scars, acne, keloid scar, or rosacea. Better understanding and optimization of EST will interest multidisciplinary research groups including surgical, biochemical and translational sciences to apply the great potential of EST in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary material

Video S1 The skin battery and the current of injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Globe Microsystems Ltd for their sponsorship to support JH and studies on wound healing. AdM is a coinvestigator of Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) project EP/L020904/1. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Vittorio Malaguti for his most helpful and insightful comments on the early drafts of this article.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kerr M. Foot care for people with diabetes: the economic case for change. NHS Diabetes; 2012. [Accessed June 1, 2016]. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/nhs-diabetes/footcare/footcare-for-people-with-diabetes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong DG, Kanda VA, Lavery LA, Marston W, Mills JL, Sr, Boulton AJ. Mind the gap: disparity between research funding and costs of care for diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):1815–1817. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Price P, European Wound Management Association Patient Outcome Group Outcomes in controlled and comparative studies on non-healing wounds: recommendations to improve the quality of evidence in wound management. J Wound Care. 2010;19(6):237–268. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.6.48471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes-UK . State of the Nation. England: 2013. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christian LM, Graham JE, Padgett DA, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress and wound healing. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13(5–6):337–346. doi: 10.1159/000104862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo S, Dipietro L. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89(3):219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eltinge EM, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Vanable JW., Jr (1986). Effects of amiloride analogues on adult Notophthalmus viridescens limb stump currents. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1986;84(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(86)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulds IS, Barker AT. Human skin battery potentials and their possible role in wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109(5):515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb07673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoare JI, Rajnicek AM, McCaig CD, Barker RN, Wilson HM. Electric fields are novel determinants of human macrophage functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;99(6):1141–1151. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0815-390R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MS, Lee MH, Kwon BJ, Koo MA, Seon GM, Park JC. Golgi polarization plays a role in the directional migration of neonatal dermal fibroblasts induced by the direct current electric fields. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(2):255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouabhia M, Park H, Meng S, Derbali H, Zhang Z. Electrical stimulation promotes wound healing by enhancing dermal fibroblast activity and promoting myofibroblast transdifferentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouabhia M, Park HJ, Zhang Z. Electrically activated primary human fibroblasts improve in vitro and in vivo skin regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(8):1814–1821. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebastian A, Syed F, McGrouther DA, Colthurst J, Paus R, Bayat A. A novel in vitro assay for electrophysiological research on human skin fibroblasts: degenerate electrical waves downregulate collagen I expression in keloid fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20(1):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Rouabhia M, Zhang Z. Pulsed electrical stimulation benefits wound healing by activating skin fibroblasts through the TGFβ1/ERK/NF-κB axis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1860(7):1551–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen DJ, James Nelson W, Maharbiz MM. Galvanotactic control of collective cell migration in epithelial monolayers. Nat Mater. 2014;13(4):409–417. doi: 10.1038/nmat3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J, Raghunathan VK, Reid B, et al. Biomimetic stochastic topography and electric fields synergistically enhance directional migration of corneal epithelial cells in a MMP-3-dependent manner. Acta Biomater. 2015;12:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Gu W, Du J, et al. Electric fields guide migration of epidermal stem cells and promote skin wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(6):840–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura KY, Isseroff RR, Nuccitelli R. Human keratinocytes migrate to the negative pole in direct current electric fields comparable to those measured in mammalian wounds. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 1):199–207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pu J, Zhao M. Golgi polarization in a strong electric field. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 6):1117–1128. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, et al. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. Nature. 2006;442(7101):457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature04925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asadi MR, Torkaman G. Bacterial inhibition by electrical stimulation. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3(2):91–97. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomes RC, Brandino HE, de Sousa NT, Santos MF, Martinez R, Guirro RR. Polarized currents inhibit in vitro growth of bacteria colonizing cutaneous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(3):403–411. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merriman HL, Hegyi CA, Albright-Overton CR, Carlos J, Jr, Putnam RW, Mulcare JA. A comparison of four electrical stimulation types on Staphylococcus aureus growth in vitro. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(2):139–146. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.02.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai H, Forrester JV, Zhao M. DC electric stimulation upregulates angio-genic factors in endothelial cells through activation of VEGF receptors. Cytokine. 2011;55(1):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai H, McCaig CD, Forrester JV, Zhao M. DC electric fields induce distinct preangiogenic responses in microvascular and macrovascular cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vascu Biol. 2004;24(7):1234–1239. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000131265.76828.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao M, Bai H, Wang E, Forrester JV, McCaig CD. Electrical stimulation directly induces pre-angiogenic responses in vascular endothelial cells by signaling through VEGF receptors. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 3):397–405. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed AF, Elgayed SSA, Ibrahim IM. (2012). Polarity effect of microcurrent electrical stimulation on tendon healing: biomechanical and histopathological studies. J Adv Res. 2012;3(2):109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asadi MR, Torkaman G, Hedayati M, Mofid M. Role of sensory and motor intensity of electrical stimulation on fibroblastic growth factor-2 expression, inflammation, vascularization, and mechanical strength of full-thickness wounds. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(4):489–498. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2012.04.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayat M, Asgari-Moghadam Z, Maroufi M, Rezaie FS, Bayat M, Rakh-shan M. Experimental wound healing using microamperage electrical stimulation in rabbits. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43(2):219–226. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.05.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borba GC, Hochman B, Liebano RE, Enokihara MM, Ferreira LM. Does preoperative electrical stimulation of the skin alter the healing process? J Surg Res. 2011;166(2):324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cinar K, Comlekci S, Senol N. Effects of a specially pulsed electric field on an animal model of wound healing. Lasers Med Sci. 2009;24(5):735–740. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurgen SG, Sayin O, Cetin F, Tuc Yucel A. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) accelerates cutaneous wound healing and inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation. 2014;37(3):775–784. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim TH, Cho HY, Lee SM. High-voltage pulsed current stimulation enhances wound healing in diabetic rats by restoring the expression of collagen, α-smooth muscle actin, and TGF-β1. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;234(1):1–6. doi: 10.1620/tjem.234.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liebano RE, Abla LE, Ferreira LM. Effect of high frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on viability of random skin flap in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21(3):133–138. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502006000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehmandoust FG, Torkaman G, Firoozabadi M, Talebi G. Anodal and cathodal pulsed electrical stimulation on skin wound healing in guinea pigs. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(4):611–618. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.01.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris KA, McGee MF, Jasper JJ, Bogie KM. Evaluation of electrical stimulation for ischemic wound therapy: a feasibility study using the lapine wound model. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301(4):323–327. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reger SI, Hyodo A, Negami S, Kambic HE, Sahgal V. Experimental wound healing with electrical stimulation. Artif Organs. 1999;23(5):460–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1999.06365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talebi G, Torkaman G, Firoozabadi M, Shariat S. Effect of anodal and cathodal microamperage direct current electrical stimulation on injury potential and wound size in guinea pigs. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(1):153–159. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.05.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taskan I, Ozyazgan I, Tercan M, et al. A comparative study of the effect of ultrasound and electrostimulation on wound healing in rats. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(4):966–972. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199709001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thawer HA, Houghton PE. Effects of electrical stimulation on the histological properties of wounds in diabetic mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(2):107–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adunsky A, Ohry A, DDCT Group Decubitus direct current treatment (DDCT) of pressure ulcers: results of a randomized double-blinded placebo controlled study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmad E. High-voltage pulsed galvanic stimulation: effect of treatment duration on healing of chronic pressure ulcers. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2008;21(3):124–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carley PJ, Wainapel SF. Electrotherapy for acceleration of wound healing: low intensity direct current. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985;66(7):443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feedar JA, Kloth LC, Gentzkow GD. Chronic dermal ulcer healing enhanced with monophasic pulsed electrical stimulation. Phys Ther. 1991;71(9):639–649. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.9.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franek A, Kostur R, Polak A, et al. Using high-voltage electrical stimulation in the treatment of recalcitrant pressure ulcers: results of a randomized, controlled clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58(3):30–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franek A, Polak A, Kucharzewski M. Modern application of high voltage stimulation for enhanced healing of venous crural ulceration. Med Eng Phys. 2000;22(9):647–655. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(00)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffin JW, Tooms RE, Mendius RA, Clifft JK, Vander Zwaag R, el-Zeky F. Efficacy of high voltage pulsed current for healing of pressure ulcers in patients with spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 1991;71(6):433–442. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.6.433. discussion 442–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houghton PE, Campbell KE, Fraser CH, et al. Electrical stimulation therapy increases rate of healing of pressure ulcers in community-dwelling people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(5):669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houghton PE, Kincaid CB, Lovell M, et al. Effect of electrical stimulation on chronic leg ulcer size and appearance. Phys Ther. 2003;83(1):17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janković A, Binić I. Frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system in the treatment of chronic painful leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300(7):377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0875-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawson D, Petrofsky JS. A randomized control study on the effect of biphasic electrical stimulation in a warm room on skin blood flow and healing rates in chronic wounds of patients with and without diabetes. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(6):CR258–CR263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundeberg TC, Eriksson SV, Malm M. Electrical nerve stimulation improves healing of diabetic ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29(4):328–331. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magnoni C, Rossi E, Fiorentini C, Baggio A, Ferrari B, Alberto G. Electrical stimulation as adjuvant treatment for chronic leg ulcers of different aetiology: an RCT. J Wound Care. 2013;22(10):525–526. 528–533. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.10.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Margara A, Boriani F, Obbialero FD, Bocchiotti MA. Frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system in the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Chirurgia. 2008;21(6):311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters EJ, Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Fleischli JG. Electric stimulation as an adjunct to heal diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(6):721–725. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santamato A, Panza F, Fortunato F, et al. Effectiveness of the frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system for the treatment of chronic and painful venous leg ulcers in older adults. Rejuvenation Res. 2012;15(3):281–287. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sebastian A, Syed F, Perry D, et al. Acceleration of cutaneous healing by electrical stimulation: degenerate electrical waveform down-regulates inflammation, up-regulates angiogenesis and advances remodeling in temporal punch biopsies in a human volunteer study. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(6):693–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ud-Din S, Perry D, Giddings P, et al. Electrical stimulation increases blood flow and haemoglobin levels in acute cutaneous wounds without affecting wound closure time: evidenced by non-invasive assessment of temporal biopsy wounds in human volunteers. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(10):758–764. doi: 10.1111/exd.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ud-Din S, Sebastian A, Giddings P, et al. Angiogenesis is induced and wound size is reduced by electrical stimulation in an acute wound healing model in human skin. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wirsing PG, Habrom AD, Zehnder TM, Friedli S, Blatti M. Wireless micro current stimulation–an innovative electrical stimulation method for the treatment of patients with leg and diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12(6):693–698. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood JM, Evans PE, 3rd, Schallreuter KU, et al. A multicenter study on the use of pulsed low-intensity direct current for healing chronic stage II and stage III decubitus ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(8):999–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vieira AC, Reid B, Cao L, Mannis MJ, Schwab IR, Zhao M. Ionic components of electric current at rat corneal wounds. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reid B, Song B, McCaig CD, Zhao M. Wound healing in rat cornea: the role of electric currents. FASEB J. 2005;19(3):379–386. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2325com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCaig CD, Rajnicek AM, Song B, Zhao M. Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(3):943–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kloth LC. Electrical stimulation for wound healing: a review of evidence from in vitro studies, animal experiments, and clinical trials. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005;4(1):23–44. doi: 10.1177/1534734605275733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferroni P, Roselli M, Guadagni F, et al. Biological effects of a software-controlled voltage pulse generator (PhyBack PBK-2C) on the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) In Vivo. 2005;19(6):949–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bevilacqua M, Dominguez LJ, Barrella M, Barbagallo M. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor release by transcutaneous frequency modulated neural stimulation in diabetic polyneuropathy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30(11):944–947. doi: 10.1007/BF03349242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bocchi L, Evangelisti A, Barrella M, Scatizzi L, Bevilacqua M. Recovery of 0.1 Hz microvascular skin blood flow in dysautonomic diabetic (type 2) neuropathy by using Frequency Rhythmic Electrical Modulation System (FREMS) Med Eng Phys. 2010;32(4):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cramp AF, Gilsenan C, Lowe AS, Walsh DM. The effect of high- and low-frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation upon cutaneous blood flow and skin temperature in healthy subjects. Clin Physiol. 2000;20(2):150–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2000.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farina S, Casarotto M, Benelle M, et al. A randomized controlled study on the effect of two different treatments (FREMS AND TENS) in myofascial pain syndrome. Eura Medicophys. 2004;40(4):293–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harding AC, Gil J, Valdes J, Solis M, Davis SC. Efficacy of a bio-electric dressing in healing deep, partial-thickness wounds using a porcine model. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58(9):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weintraub MI, Wolfe GI, Barohn RA, et al. Static magnetic field therapy for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;84(5):736–746. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldman R, Rosen M, Brewley B, Golden M. Electrotherapy promotes healing and microcirculation of infrapopliteal ischemic wounds: a prospective pilot study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17(6):284–294. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song B, Gu Y, Pu J, Reid B, Zhao Z, Zhao M. Application of direct current electric fields to cells and tissues in vitro and modulation of wound electric field in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(6):1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang ET, Zhao M. Regulation of tissue repair and regeneration by electric fields. Chin J Traumatol. 2010;13(1):55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xiong GM, Do AT, Wang JK, Yeoh CL, Yeo KS, Choong C. Development of a miniaturized stimulation device for electrical stimulation of cells. J Biol Eng. 2015;9(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13036-015-0012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Caddy J, Wilanowski T, Darido C, et al. Epidermal wound repair is regulated by the planar cell polarity signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;19(1):138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allen GM, Mogilner A, Theriot JA. Electrophoresis of cellular membrane components creates the directional cue guiding keratocyte galvanotaxis. Curr Biol. 2013;23(7):560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun Y, Do H, Gao J, Zhao R, Zhao M, Mogilner A. Keratocyte fragments and cells utilize competing pathways to move in opposite directions in an electric field. Curr Biol. 2013;23(7):569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Torres AS, Caiafa A, Garner AL, et al. Platelet activation using electric pulse stimulation: growth factor profile and clinical implications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3 Suppl 2):S94–S100. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. (2004). Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56(4):549–580. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(5):585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reid B, Song B, Zhao M. Electric currents in Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009;335(1):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang Y, Zhang H, Lin ZH, et al. Human skin based triboelectric nano-generators for harvesting biomechanical energy and as self-powered active tactile sensor system. ACS Nano. 2013;7(10):9213–9222. doi: 10.1021/nn403838y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shi M, Zhang J, Chen H, et al. Self-powered analogue smart skin. ACS Nano. 2016;10(4):4083–4091. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gharibi R, Yeganeh H, Rezapour-Lactoee A, Hassan ZM. (2015). Stimulation of wound healing by electroactive, antibacterial, and antioxidant polyurethane/siloxane dressing membranes: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(43):24296–24311. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b08376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ge J, Neofytou E, Cahill TJ, 3rd, Beygui RE, Zare RN. Drug release from electric-field-responsive nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2012;6(1):227–233. doi: 10.1021/nn203430m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murdan S. Electro-responsive drug delivery from hydrogels. J Control Release. 2003;92(1–2):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weaver CL, LaRosa JM, Luo X, Cui XT. Electrically controlled drug delivery from graphene oxide nanocomposite films. ACS Nano. 2014;8(2):1834–1843. doi: 10.1021/nn406223e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akturk O, Kismet K, Yasti AC, et al. Collagen/gold nanoparticle nano-composites: a potential skin wound healing biomaterial. J Biomater Appl. 2016;31(2):283–301. doi: 10.1177/0885328216644536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Griffin DR, Weaver WM, Scumpia PO, Di Carlo D, Segura T. Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks. Nat Mater. 2015;14(7):737–744. doi: 10.1038/nmat4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yu B, Kang SY, Akthakul A, et al. An elastic second skin. Nat Mater. 2016;15(8):911–918. doi: 10.1038/nmat4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chung E. PrintAlive 3D skin tissue printer wins Canadian Dyson Award. Available from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/printalive-3d-skin-tissue-printer-wins-canadian-dyson-award-1.2770667.

- 94.de Mel A. Three-dimensional printing and the surgeon. Br J Surg. 2016;103(7):786–788. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shen Q, Trabia S, Stalbaum T, Palmre V, Kim K, Oh IK. A multiple-shape memory polymer-metal composite actuator capable of programmable control, creating complex 3D motion of bending, twisting, and oscillation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24462. doi: 10.1038/srep24462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Markov MS. Electromagnetic Fields in Biology and Medicine. CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1 The skin battery and the current of injury.