Abstract

Establishing the validity of health behavior surveys used in community-based participatory research (CBPR) in diverse populations is often overlooked. A novel, group-based cognitive interviewing method was used to obtain qualitative data for tailoring a survey instrument designed to identify barriers to improved cardiovascular health in at-risk populations in Washington, DC. A focus group–based cognitive interview was conducted to assess item comprehension, recall, and interpretation and to establish the initial content validity of the survey. Thematic analysis of verbatim transcripts yielded 5 main themes for which participants (n = 8) suggested survey modifications, including survey item improvements, suggestions for additional items, community-specific issues, changes in the skip logic of the survey items, and the identification of typographical errors. Population-specific modifications were made, including the development of more culturally appropriate questions relevant to the community. Group-based cognitive interviewing provided an efficient and effective method for piloting a cardiovascular health survey instrument using CBPR.

Keywords: Survey instrument, cognitive interviewing, community-based participatory research, health behaviors, cardiovascular health

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increasingly a threat to both developed and developing countries.1 The risk factors that continue to jeopardize cardiovascular health and precede CVD onset—diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and smoking—disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minority populations and those of lower socioeconomic status.2,3 Although CVD remains the leading cause of death in the United States,4 non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods with greater socioeconomic deprivation, and these environments appear to worsen cardiovascular health.5 Interventions that improve cardiovascular health are needed to reach at-risk populations in resource-limited communities.5

Community-based interventions that combine education, support, and resources to target cardiovascular health6 are essential for reducing CVD. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a strategy for developing interventions with community partnerships for population-specific and sustainable interventions both in the United States7 and abroad.8–10

A reliable and valid survey instrument is fundamental for measuring health beliefs and practices, such as physical activity and diet, in a community-based intervention; however, little is known about how best to tailor health behavior surveys to fully assess a community’s needs. Cognitive interviewing (CI) is a well-established method for providing insight into the respondent’s cognitive processes in survey completion—specifically, question comprehension, information retrieval, decision making, and response processing. Cognitive interviewing is an approach that has been used in community-based studies of diverse populations to validate the utility and relevance of patient/participant-reported outcome measures as an important adjunct to traditional pilot testing.11 Historically, cognitive interviews have been conducted via face-to-face interviews, with one individual at a time.12,13 Community-based participatory research studies have evaluated community involvement in health survey development; however, there are few published studies that we are aware of describing focus group–based CI for survey development14–17 and for purposes of quantitative studies.18

In the selected faith-based Washington, DC, communities in the United States, we examined focus group–based CI as a method for developing a survey to assess cardiovascular health beliefs and behaviors in a CBPR project. This novel application of CI with a focus group design was used to (1) assess question comprehension and interpretation, (2) evaluate content validity, (3) determine unforeseen inaccuracies in cultural conversion of survey questions, and (4) pilot-test and evaluate the feasibility of a novel data collection approach to enhance data quality. We hypothesized that group-based CI would serve as a cost-effective and efficient method of gaining feedback on a survey measuring cardiovascular health beliefs and behaviors for a population-based cohort in at-risk, resource-limited Washington, DC, communities.

Methods

A CBPR partnership, The D.C. Cardiovascular Health and Obesity Collaborative (D.C. CHOC), was established in 2012 and is made up of our multidisciplinary research group (including physicians, health behaviorists, mixed methodologists, epidemiologists, and research fellows), Howard University faculty in nutrition and community health, and church leaders from predominantly African American, faith-based organizations in Washington, DC (wards 5, 7 and 8; areas of the city with the highest CVD prevalence and where access to physical activity resources and healthy nutrition is limited19). Additional partners include health care providers, leaders from nonprofit organizations, government agencies, and community members. The Washington, D.C. Cardiovascular Health and Needs Assessment is the first research project designed by D.C. CHOC with the overarching goals to (1) assess cardiovascular health factors of a sample population from the faith-based community in resource-limited Washington, DC, areas; (2) evaluate technological tools for improving health behaviors related to physical activity and diet; and (3) assess potential psychosocial and environmental barriers to behavior change. The D.C. Cardiovascular Health and Obesity Collaborative has been providing input on project design since its inception, including recommending an initial focus group to evaluate the survey prior to administering it to the community. The Washington, D.C., Cardiovascular Health and Needs Assessment project, including the evaluation of focus group CI as a method for survey testing, was approved by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Institutional Review Board (NCT#01927783). We obtained written informed consent from all study participants.

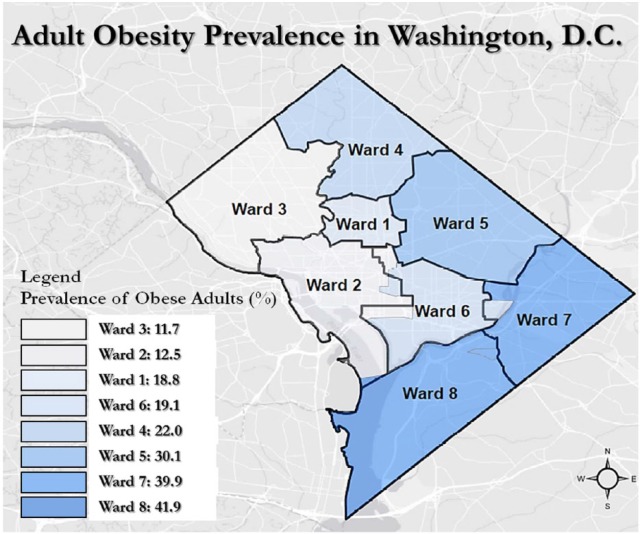

The final CI focus group participants (n = 8) were recruited between December 2013 and January 2014 from 3 churches in 3 resource-limited wards in Washington, DC. Participants were aged 28 to 70 years and were proficient in English. A moderator-led focus group using group-based CI techniques was conducted with participants at one of the collaborating churches in February 2014. The participants of the CI focus group represented a purposive sample of church lay leaders or members from predominantly African American churches in 3 Washington, DC, wards where obesity prevalence is highest and resources for physical activity and healthy nutrition are most limited (see Figure 1). Each of 3 churches was asked to provide a list of 5 volunteers (total n = 15) who would be interested in enrolling in the focus group discussions. The members who were identified were then contacted by phone. Of the 15 participants contacted, 9 agreed to participate based on scheduling; however, 1 participant was unable to attend and dropped out at the last minute, leaving 8 participants (Table 1). Focus group participants initially completed the cardiovascular health beliefs and behaviors survey individually. The participants were then asked to individually rate the difficulty of each question immediately after completing the question by selecting one of the 2 responses, “Easy” vs “Difficult,” next to each item.

Figure 1.

Washington, DC, wards with obesity prevalence (Government of District of Columbia Department of Health; Center for Policy, Planning and Evaluation; and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System “Obesity in the District of Columbia,” 2009).

Table 1.

Participant baseline characteristics in the CV Health and Needs Assessment Qualitative Study (n = 8).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Female | 3 (37.5) |

| Male | 5 (62.5) |

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 53.3 (12.2) |

| Range | 28–70 |

| Race, No. (%) | |

| Black/African American | 8 (100) |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | |

| Single | 1 (12.5) |

| Married | 7 (87.5) |

| Education, No. (%) | |

| Some college | 3 (37.5) |

| College degree | 2 (25.0) |

| Technical degree | 1 (12.5) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 2 (25.0) |

| Annual household income, No. (%) | |

| <$60 000 | 2 (28.6) |

| ⩾$60 000 | 5 (71.4) |

Once the survey was completed individually, focus group–based CI began and lasted 54 minutes. The participants were permitted to refer back to their completed survey during the focus group. An experienced moderator (G.R.W.) led the focused discussion, whereas a facilitator (T.P.-W.) took notes, made observations, and operated an audio recorder. The moderator had not met the participants prior to the focus group. A Moderator’s Guide with pre-selected questions and probes was used (Table 2). As part of the CI process, participants were asked to perform an initial think-aloud exercise to practice their ability to answer open-ended13 and probing questions designed to identify any difficulties participants experienced when completing the survey. The initial think-aloud exercise was adapted from the Willis Cognitive Interviewing and Survey Design: A Training Manual12 and has been used in other community settings in traditional one-on-one cognitive interviews.11

Table 2.

Focus group’s Moderator Guide, CV Health and Needs Assessment Qualitative Study.

| Moderator Guide |

|---|

|

Think-aloud exercise

Before beginning questions about the survey instrument, participants were asked to perform the following think-aloud exercise: |

| “While we are going through the questions, I’m going to ask you to think aloud so that I can understand if there are problems with the questionnaire. By ‘think aloud’ I mean repeating all the questions aloud and telling me what you are thinking as you hear the questions and as you pick the answers. Here is an example: Visualize the place where you live and think about how many windows there are in that place. When you are counting the windows tell me what you are seeing and thinking.” |

| Focus group questions |

| 1. On page___, were there any questions on this page (on the questionnaire) that were difficult to understand? If so, please tell me the question number on the survey that you identify as being “difficult”? 2. For the questions that you identified as “difficult” or an issue area, could you please tell me why you felt they were difficult? |

| Probe |

| What do you think the question is asking? |

| What do the specific words mean to you? |

| What type of information did you need to recall (remember) to answer the question? For example do you recall things individually or do you estimate to answer the question? |

| Do you have to devote mental effort to answer thoughtfully and accurately? |

| 3. After each difficult question, please ask the participant for recommendations on modifying/revising the question for participant comfort. |

| Moderator continued to probe after each question to get participant’s perspective on the difficulty with the study question. |

| 4. What are your thoughts regarding the length of the questionnaire? |

| 5. Is it possible that any of the items may be considered too personal or too offensive to answer? |

| Moderator probed: Which items? Please describe in as much detail as you can. |

| 6. What suggestions do you have for improving the questionnaire? |

| 7. Were there any questions regarding health beliefs or health behaviors left out that you would like to see included? |

| 8. What do you see as potential barriers to filling out the questionnaire? |

| Moderator listed and acknowledged all barriers identified and then further probed these issues. |

| Closing questions: wrap-up |

| 1. If you were in charge of a research project to look at health beliefs and health behaviors of this community, what would be one piece of advice that you would give the research team before beginning the study? |

| 2. One last question: Are there any other things about your experiences as members of this community that we haven’t discussed but you would like to share? |

Qualitative Analysis

The CI focus group was audio-recorded with the recording transcribed verbatim by an independent clinical research organization (Social Solutions International, Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA). A member of the research team listened to the audio files to validate the quality of the verbatim transcription. Once the quality of the audio transcripts was verified, 4 members of the research team independently reviewed the transcripts and later met as a group through 2 rounds of consensus building of the major themes. Once consensus was reached, the 4 research team coders developed a thematic codebook or dictionary of concepts based on the participant responses.

Each code was accompanied by an operational definition that allowed clarity and consistency in the coding process. Once the process of consensus building was complete, the themes and coding were validated by a National Institutes of Health intramural qualitative expert. “Creditability, auditability, and fittingness”20 were criteria by which we assessed trustworthiness of data. To ensure creditability or “truth” of the findings,19 themes and coding were validated by an intramural mixed-methods expert. To maintain auditability (ie, “the adequacy of the information leading the reader from the research question and raw data through various steps of analysis to the interpretation of findings”) and fittingness, or “faithfulness to everyday reality of participants” of the qualitative data, selected quotes illustrative of each designated theme are displayed in Table 3 to highlight pertinent findings.20 NVivo 9.0 software was utilized for further qualitative data management and analysis of the transcripts.

Table 3.

Focus group themes, subthemes, and quotes, CV Health and Needs Assessment Qualitative Study.

| Themes and subthemes | Illustrative quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Question improvement | ||

| Questions on physical activity | “. . . Page 4, Question 16, ‘How much time do you usually spend sitting. . .’ It’s a fine question but I think it should be broken up between work and non-work time, which may be a little clearer for folks, some other people that are going to take the survey. . .” (Male, 55) | |

| “. . . of the things on the exercise part that was confusing to me was it said “Does your work involve moderate intensity activity such as brisk walking?. . . walking to and from is part of my commute. . . I don’t see any place where that goes. . .” (Male, 49) | ||

| Questions on eating | “[Question reads] ‘During the past month, how often did you eat the following? Please fill the number of times per day, per week, per month’. . . I thought that once you start getting down to the itemized items [types of foods] that they were grouped too much together. . .” (Female, 59) | |

| “[One question asks about] ‘foods prepared outside of the home’, then you talked about breakfast, lunch and dinner [in] places such as McDonalds [in another question]. . . I didn’t understand why some [fast food] restaurants are listed but are not part of the previous question [about foods prepared outside of the home]. . .” (Male, 49) | ||

| Questions on drinking | “. . . [the question on drinking] ‘regular soda’, there is nothing about coffee on here, If I’m a coffee drinker, would that go under any of these categories as far as drinks on the first page?” (Male, 49) | |

| “. . . I see soda and pop [consumption are asked about] in here and those are typically caffeinated so we might want to add coffee and then specify, categorize it as caffeine drinks, to see how much caffeine people are [drinking]. . .” (Female, 43) | ||

| Formatting scales/responses | “Page 10 question 47 and when I take surveys, I like to have the survey broken up a little bit and I think 47 is a great place for you to consider using a. . . scale. . . sometimes people may have difficulty saying well, the overall healthcare you receive, I could give it a grade” (Male, 55) | |

| “And on page 14, 62, and 65, it was confusing to me. . . not clear if you want one answer or multiple. . . indicate what more. . . ”How did you try to lose weight?”. . .” (Female, 59) | ||

| “Question 52 in the weight history, where it had the pictures of the men and the women; that was a little confusing for me. . . pictures when it asks me if I want to look like. . . I don’t want to look like any of them. . . I’m just not sure how to judge these pictures. . .” (Male, 49) | ||

| “I think it’s about the graphics at the end of the day. . . giving them more a real picture of an actual person. . .” (Male, 28) | ||

| Consistency/timing of questions | “Well the first sentence just confused me, because it said the past month, I wasn’t sure if that was inclusive of today, the last thirty days or previous month. . .” (Male, 49) | |

| “Well some of the questions later on said the “the last 30 days” and you know, you could put the word inclusive or not you know ‘the last 30 days including today, or the last 30 days not including today’” (Male, 49) | ||

| Clarifications of definitions | “And with the drinking [alcohol] piece. . . that might be one you want to add “Elect not to answer”, just add that in and you’ll know that there’s some issue with answering the question, rather than somebody just saying “No” when they may be a drinker and because this is being conducted in a church. . . may elect not to answer. . .” (Female, 59) | |

| 2. Suggestions for additional questions | ||

| Health behavior–related questions | “. . . you don’t ask any questions about sexual activity, and if it is. . . if you have some cardiovascular issues, is that important or not?. . . but you don’t address it for a person who’s taking a medication or maybe taking something for erectile dysfunction or, is that, I think those things, when I heard, affect your heart. . . ” (Male, 55) | |

| “I would like to see questions related to, on the survey, how often, if you are on Lipitor for cholesterol or blood pressure meds, if people are. . . I mean how consistent you are with taking your meds. . . I know for myself. . . [I]was in denial. . . and I elected not to take the meds. . . if I increase my exercise and modify my diet, I don’t have to take these pills. . . other than just saying “I’m hopeless; I just have to take these pills, there is no other alternative”. . . so I don’t want to feel hopeless like “I have to take these meds to live”, there’s ways, things that I can do, to offset that, until such time as that doesn’t work anymore and I have to take the meds. . .” (Female, 59) | ||

| “You ask about cigarettes and drinking but you don’t ask about marijuana or electronic cigarettes or other products. . . crack or cocaine use or things like that. . . and I think, you know, narcotics and other substances should be covered. . .” (Male, 49) | ||

| Complementary alternative medicine (CAM)–related Questions | “You know, I think because like [says names] can be an in-class example of how people tend to think about their circumstances when they’ve been diagnosed with high cholesterol or diabetes and high blood pressure, and the list starts mounting up of things that you’re getting as you’re getting older, I think questions in there that gear towards holistic alternatives and other things that you can do to offset, I think those questions being built would help. . . ” (Female, 59) | |

| “But you should ask what alternative meds we are taking. . . because you should track what kind of vitamins, how many aspirins, like, I would take a daily aspirin even though the doctor hasn’t told me to be on an aspirin regimen, I might do my own little aspirin regimen just because. . . those are the kind of things you probably want to track. . .” (Male, 49) | ||

| Questions on self-efficacy | “But the reason I’m doing it is because I’m trying not to take medicine. . . she makes a good point in that we’ve been prescribed medicine but we don’t want to take it and we’re taking alternatives so we don’t have to take it. . .” (Male, 49) | |

| “. . . I feel hopeless [when] I’m stuck on taking something the doctor has prescribed because [I think] there is no other alternative when. . . there is” (Female, 59) | ||

| 3. Community-specific issues | ||

| Potentially sensitive topics | “I did have a comment. . . under 19 tobacco and only because. . . that your target audience would be churches and, even though the survey is confidential, you pose the risk of not getting a true answer. . .” (Female, 43) | |

| “Well I think it. . . again, if this survey is going to be put before the church you typically targeting the church, you will fall into what [says name] talked about in terms of drinking, if people aren’t married and that kind of thing, you may not get a true answer [when asking about sexual activity]. . .” (Female, 59) | ||

| Suggestions for tailoring to the community | “I don’t think [the questions were too long]. . . I think those were solid questions. . . in this case, longer may be better because you want to get as much info from them as possible. . .” (Male, 55) | |

| 4. Skip logic of questions | ||

| “. . . when you asked the question. . . and you answer no and it says go to question 20, well I went immediately to question 20 and didn’t think I should have answered all the other questions in between. . . but then as I started reading back [and realized], some of the other [questions], like question 4 addresses a different level of activity. . .” (Female, 43) | ||

| “I have one [says name]. . . Question 44 and 45, if you answer 44 positively “If you do go to a clinic or health center regularly” then 45 is not applicable; 45 says “What’s the main reason you do not have a usual source of medical care?” well if you answer “I do have a source” in 44, then 45 is not applicable.” (Male, 70) | ||

Results

Of the 8 focus group participants, 62.5% (n = 5) were men and all were African American (Table 1). Regarding education, 37.5% (n = 3) of participants obtained some level of college education, 25% (n = 3) had received a college degree, 12.5% (n = 1) completed a technical degree, and 25% (n = 2) received a graduate/professional degree. Seventy-one percent (n = 5) reported having an annual household income less than $60 000.

Thematic analysis of the CI focus group verbatim transcripts yielded 5 main themes for which participants suggested survey modifications, including item improvements, suggestions for additional items, community-specific issues, the skip logic of the survey items, and the identification of typographical errors (Supplemental Table 1). The participant recommendations included (1) improving specific items related to physical activity, eating, and drinking; (2) reformatting scales/responses; (3) modifying consistency/timing of survey items, and (4) clarifying definitions. Under the “suggestions for additional questions” theme, participants recommended inclusion of items related to specific health behaviors, including complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use and perceived self-efficacy.

Quantitative analysis in NVivo 9.0 provided percentage coverage of each theme and subtheme coded based on participant feedback. The percentage coverage of themes in descending order was question improvement (58%), additional questions (17%), community-specific issues (9%), skip logic (7%), and typographical errors (2%). These percentages are referring to the proportion of quotes falling under each of the top 5 themes.

Strategies were suggested to improve various sections of the survey, as demonstrated by themes’ illustrative quotes (Table 3). A reoccurring subtheme was the need to reformat scales and responses and to clarify terms used in specific questions related to physical activity, dietary intake, and weight history (eg, time frame and frequency of dietary intake). In Table 3, it was suggested to reformat the dietary questions to reflect a more accurate interpretation of intake related to specific foods. Participants also described challenges with vaguely defined terms used in physical activity questions. The need for further modification of language in physical activity questions also surfaced from this statement. There was consensus among other participants regarding use of more detailed language in the dietary questions. Quotes described participants’ difficulty when mapping internally generated answers12 to responses given by the survey questions.

Further modifications were suggested for the body size perception “graphics.” (Male, 28) It was suggested that “a real picture of an actual person” (Male, 28) be used in the section on Weight History as opposed to a pictorial representation as described by Pulvers et al21:

“It was tough because it also seemed a little ethnocentric; it seemed like these are white bodies or something. . .” (Male, 49)

Changes were made to the survey based on feedback received from group-based CI participants (Table 4). Each change was a direct response to the participants’ suggestions for reformatting scales and responses, clarifications of terms in the questions through language and figure modification, or inclusion of more culturally relevant, community-specific questions. Physical activity questions were differentiated between work-related physical activity and fitness or recreational physical activity. Dietary intake questions were reformatted into tables to guide respondent’s information processing. Language was modified throughout the survey to lessen stigma (eg, providing the option for “Prefer not to answer” responses for questions on “Tobacco/Alcohol/Drug History”) and to elicit comprehensive information on beliefs and behaviors, as demonstrated by the changes made to questions on dietary intake frequency and addition of health behavior–related questions (medication and illicit drug usage, sexual function, CAM) and self-efficacy questions.

Table 4.

Changes made to cardiovascular health survey for use in broader community, CV Health and Needs Assessment Qualitative Study.

| Theme and subthemes | Changes made | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Question improvement | |

| Questions on physical activity | Differentiated work-related physical activity from fitness or recreational (leisure) physical activity | |

| Questions on eating | Reformatted questions into tables to allow for improved information processing of questions asked | |

| Questions on drinking | Added questions on caffeine intake | |

| Formatting of scales/responses | Provided option for “prefer not to answer” responses for “Tobacco/Alcohol/Drug History” to lessen stigma and provide comprehensive information on beliefs and behaviors pertaining to category | |

| Sections: Overall health, health care access and utilization, weight history | ||

| Grouped related questions into a table | ||

| Section: Weight history | ||

| Replaced drawings with images to provide more accuracy | ||

| Section: Part 2. Other information | ||

| Consistency | Used more detailed language to describe time interval for which to provide information about dietary intake (ie, per day, per week, or per month) | |

| Clarification of definitions | Differentiated work-related physical activity from fitness or recreational (leisure) physical activity | |

| 2 | Suggestions for additional questions | |

| Sections added: Complementary alternative medicine (CAM), sexual function | ||

| Additional questions added on self-efficacy | ||

| Questions added on illicit drug use and medication usage | ||

| 3 | Community-specific issues | |

| Added a “prefer not to answer” category for answers to sensitive questions | ||

Discussion

We used focus group–based CI in a community-based focus group to tailor a survey for measuring psychosocial and environmental factors related to cardiovascular health in resource-limited Washington, DC, neighborhoods. The themes and subthemes coded from the qualitative focus group data elicited key recommendations for survey modifications specific to the needs of the target community. Using CI techniques, including the “think-aloud” process, and discussing specific issues regarding comprehension, information retrieval, decision making, and response processing, we were able to focus on improving the reliability and validity of the cardiovascular health survey. Through group discussion, we were able to pilot-test and evaluate the feasibility of a novel data collection approach to enhance data quality, to assess question comprehension and interpretation, and to evaluate content validity of individual items and overarching concepts of interest, such as physical activity at home and/or work. The goal of determining unforeseen inaccuracies in cultural conversion of survey questions was met, including the discovery that participants found diagrams that were designed to assess body image did not meet what they perceived as cultural congruity. These findings suggest the use of novel CI focus group techniques to gather qualitative data in a group-based setting may be an efficient mechanism for feedback from community members about a survey for measuring cardiovascular health beliefs and behaviors. Although the cost and efficiency of these methods were not quantitatively tested as part of this study, when we set out to try the CI techniques that are typically done with 10 to 15 individual face-to-face interviews in a group setting, we found we were able to conduct the assessment in 1 group format rather than multiple interviews, which would have likely taken 10 times as long, thus increasing the time required of the interviewers and the need for an additional space commitment. This study builds on prior work using CI techniques in community-based settings for the development of research tools tailored to the needs and desires of the at-risk community.11

Qualitative research implications

The use of focus groups in CBPR is instrumental in providing researchers with qualitative data about community-specific barriers to developing appropriate interventions for health promotion and intervention.22 Accountability establishes a credible and culturally sensitive programming ethic, a shared understanding of the research process, and a consensus on research goals.23 Cognitive interviewing in a group setting reinforced accountability between respondents, the moderator, and the facilitator. This technique allowed participants to share their perspectives and recognize the challenges faced by researchers in appropriately addressing their health needs. Group-based CI lessened facilitator burden and promoted open-ended dialogue among participants that would not have been facilitated by a one-on-one interview. Participants provided responses that informed modifications to the survey for a broader community-based population. Such responses highlighted the need to include questions on a health behavior associated with CVD risk that were previously excluded due to perceived stigma and triggered an insightful dialogue between both facilitators and participants.

The CI focus group technique served as a method for (1) question improvement, (2) developing additional questions of interest, (3) exploring community-specific issues, (4) clarifying skip logic, and (5) correcting typographical errors. Cognitive interviewing in a group setting provided a method for decreasing interviewer bias by facilitating the participant’s control of the discussion. In addition, accountability present in the group-based CI fostered valuable exchange of community perspectives on the strengths and weaknesses of the survey.

Group-based CI encouraged participants to identify cultural, structural, and linguistic barriers in the survey. Left unaddressed, these barriers may have increased miscomprehension of the survey question (eg, question intent, meaning of terms) and attenuated participants’ ability to accurately respond to survey questions. Group-based CI within the target population appears to be an effective mechanism for culturally relevant feedback on the survey tool because participants have significant experience with the topics covered by the survey, a necessary element when conducting CI for survey development.12 Participants’ willingness to engage facilitators on health topics seldom discussed due to ascribed stigmas within faith-based populations elucidated key limitations in the current language used to survey these topics.

Understanding stigma associated with survey tools used to assess health beliefs and behaviors is essential to the design of culturally sensitive interventions. Successful interventions aimed at being culturally responsive to cardiovascular risk factors within a predominantly African American, faith-based community should reflect consideration of the cultural perspectives on diet, physical activity, weight, and other health-related behaviors. Group-based CI facilitates detection of lingual and format limitations in survey design to ensure culturally competent assessment of the target population.

Implications for health behavior interventions in faith-based communities

Recruiting congregants from predominantly African American churches provided an effective strategy for tailoring the survey specific to this community. The setting for the group CI may have been a more comfortable environment for the participants because of an established support network. This preexisting supportive social structure is consistent with faith-based settings, which appear to be culturally relevant environments for behavior-based interventions.24–26 The longstanding role of faith-based organizations as leaders in the African American community makes these institutions ideal hubs for informing behavioral change specific to the target population, disseminating health information, and identifying key community leaders who can steer a community-based intervention.23,26 Studies in faith-based settings, such as the Strawbridge Prospective Study, suggest that religious involvement is associated with improving and maintaining health behaviors related to tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity,27 all of which are key determinants of cardiovascular outcomes. Prior work demonstrates that church-based populations in the African American community have high rates of obesity and would specifically benefit from programs to provide tools for improving the quality of physical activity.28,29

Global health implications

Cardiovascular disease is an increasing health burden in both developed and developing countries.1 Studies suggest that community participation in research study development is gaining recognition as an effective practice globally8–10 and that CI can be used in diverse populations.16 In a recent study in a Vietnamese population, CI served as an informative method to translate, clarify, and contextualize a survey measuring the perceived aspects of the community’s local health care services.14 Another study assessed the face validity and cultural relevancy of 2 pain scales in a Kenyan community.15 With regard to surveying risk factors leading to CVD, CI served as a useful method to assess the content retention and cultural relevancy for a health education study about a family’s eating style and its impact on dietary intake among an older Vietnamese American sample.17 However, our findings are particularly unique by highlighting that group-based CI can be beneficial for survey development. Future studies evaluating survey instruments in global health interventions addressing CVD risk might benefit from group-based CI methods. As CI can be used as an effective CBPR measuring tool, it also shows opportunity for informing the inferences from quantitative studies.18 Future work should elucidate the role of group-based CI in this capacity.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are the novel use of CI in a group-based setting and the incorporation of CBPR strategies. We provided briefings of the findings back to participants and to the DC CHOC. These briefings included a short PowerPoint presentation. During the briefings, we also tried to determine the best methods for dissemination to the community. The community members recommended briefs that could be shared with the community, which we created and shared with congregants of the participating churches. We shared the briefs in bulletins and announcements and through e-mails with the churches, reaching more than 1000 community members in the distribution. One potential limitation of the study is generalizability, given that we conducted our focus group in a primarily African American, faith-based setting with a small sample size. All preferences and suggestions made in the focus group may not be representative of the entire targeted population. A limitation of this study was the use of a single focus group. Although focus groups usually continue until data saturation is reached and no new themes are generated, with a single focus group this may not have occurred.

Conclusions

As hypothesized, group-based CI facilitated the community-driven development of a culturally relevant survey that assesses health beliefs and behaviors related to cardiovascular health in an at-risk population. Unlike the previous use of CI in one-on-one interviews, in which discussion is naturally controlled by the interviewer, the novel use of the CI in a group setting reduces interviewer biases by giving the respondents control of the discussion and information exchange, without imposing respondent burden. A community-based setting allows members to articulate their perspectives in a comfortable and familiar environment that encourages authentic dialogue. Group-based CI may be an effective and efficient method for development of survey instruments for community-based interventions targeting cardiovascular health. The survey developed using this rigorous process will continue to be psychometrically tested, including exploring internal reliability of specific scales in descriptive and intervention studies planned in these resource-limited communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participating church communities for warmly welcoming our research team and providing feedback from preliminary stages. In addition, we acknowledge the D.C. CHOC for their contribution, as without their insightful recommendations, this project would not have come to fruition.

Footnotes

Peer review:Three peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1695 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number: ZIA HL006168).

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: TP-W and GRW conceived and designed the experiments. TP-W, GRW, JNS, ATB, MM, and ST analyzed the data. JNS and GRW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JNS, GRW, TP-W, ATB, and ST jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. TP-W made critical revisions and approved the final version. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors agreed with manuscript results and conclusions.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human Participants: All procedures involving human participants performed in the Washington, DC, CV Health and Needs Assessment study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Institutional Review Board study and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1. Aje M. Cardiovascular disease: a global problem extending into the developing world. World J Cardiol. 2009;1:3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mensah GA. Eliminating disparities in cardiovascular health: six strategic imperatives and a framework for action. Circulation. 2005;111:1332–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Powell-Wiley TM, Ayers C, Agyemang P, et al. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic deprivation predicts weight gain in a multi-ethnic population: longitudinal data from the Dallas Heart Study. Prev Med. 2014;66:22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fuster V, Kelly B. Summary of the institute of medicine report promoting cardiovascular health in the developing world. Glob Heart. 2011;6:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pearson TA, Palaniappan LP, Artinian NT, et al. American Heart Association Guide for Improving Cardiovascular Health at the Community Level, 2013 update: a scientific statement for public health practitioners, healthcare providers, and health policy makers. Circulation. 2013;127:1730–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones A, Mango J, Jones F, Lizaola E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:346–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, et al. An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects. Soc Ment Health. 2011;1:185–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mercer S, Murphy D. Validity and reliability of the CARE Measure in secondary care. Clin Govern: Int J. 2008;13:269–283. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wallen GR, Middleton KR, Rivera-Goba MV, Mittleman BB. Validating English- and Spanish-language patient-reported outcome measures in underserved patients with rheumatic disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willis G. Cognitive Interviewing, Design: A Training Manual (Working Paper No.7). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willis G. Survey Cognitive Interview A “How To” Guide. Rockville, MD: Research Triangle Institute; 1999;. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duc DM, Bergström A, Eriksson L, Selling K, Ha BTT, Wallin L. Response process and test–retest reliability of the Context Assessment for Community Health tool in Vietnam. Global Health Action. 2016;9:31572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang KT, Owino C, Vreeman RC, et al. Assessment of the face validity of two pain scales in Kenya: a validation study using cognitive interviewing. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nápoles-Springer AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H, Stewart AL. Using cognitive interviews to develop surveys in diverse populations. Med Care. 2006;44:S21–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nguyen BH, Nguyen CP, McPhee SJ, Stewart SL, Bui-Tong N, Nguyen TT. Cognitive interviews of Vietnamese Americans on healthy eating and physical activity health educational materials. Ecol Food Nutr. 2015;54:455–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campanelli P, Gray M, Blake M, Hope S. Cognitive interviewing as tool for enhancing the accuracy of the interpretation of quantitative findings. Qual Quant. 2016;50:1021–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of Health. Obesity in the District of Columbia, 2014. https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/Obesity%20Report%202014.pdf

- 20. Barroso J. Qualitative approaches to research. In: LoBiondo-Wood GHJ, ed. Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010:109–131. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pulvers KM, Lee RE, Kaur H, et al. Development of a culturally relevant body image instrument among urban African Americans. Obes Res. 2004;12:1641–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wallen GR, Rivera-Goba MV. From practice to research: training health care providers to conduct culturally relevant community focus groups. Hisp Health Care Int. 2003;2:129–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Timmons SM. Pastors’ influence on research-based health programs in church settings. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2009;3:Article 8. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blumenthal DS, Braithwaite R, Smith S. Community-Based Participatory Health Research. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Butler-Ajibade P, Booth W, Burwell C. Partnering with the black church: recipe for promoting heart health in the stroke belt. ABNF J. 2012;23:34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pargament K. Faith and health behavior: the role of the African American church in health promotion and disease prevention. In: Pargament K, ed. APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013:439–459. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Felix Aaron K, Levine D, Burstin HR. African American church participation and health care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:908–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cline KM, Ferraro KF. Does religion increase the prevalence and incidence of obesity in adulthood? J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45:269–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell-Wiley TM, Banks-Richard K, Williams-King E, et al. Churches as targets for cardiovascular disease prevention: comparison of genes, nutrition, exercise, wellness and spiritual growth (GoodNEWS) and Dallas County populations. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.