Abstract

Disruption of blood flow promotes endothelial dysfunction and predisposes vessels to remodeling and atherosclerosis. Recent findings suggest spatial and temporal tuning of local Ca2+ signals along the endothelium is vital to vascular function. In the current study, we examined whether chronic flow disruption causes alteration of dynamic endothelial Ca2+ signal patterning associated with changes in vascular structure and function. For these studies, we performed surgical partial-ligation (PL) of the left carotid arteries of mice to establish chronic low flow for 2 weeks; right carotid arteries remained open and served as controls (C). Histological sections showed substantial remodeling of PL compared to C arteries, including formation of neointima. Isometric force measurements revealed increased phenylephrine-induced contractions and decreased KCl-induced contractions in PL verses C arteries. Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in response to acetylcholine (ACh; 10−8 - 10−5 M) was significantly impaired in PL verses C vessels. Evaluation of endothelial Ca2+ using confocal imaging and custom analysis exposed distinct impairment of Ca2+dynamics in PL arteries, characterized by reduction of active sites and truncation of events, corresponding with attenuated vasorelaxation. Our findings suggest that endothelial dysfunction in developing vascular disease may be characterized by distinct shifts in the spatial and temporal patterns of localized Ca2+ signals.

Keywords: Partial ligation, low flow, endothelium, calcium, vasorelaxation

Introduction

Endothelial dysfunction is a harbinger of serious cardiovascular disease including coronary and peripheral artery disease [1–4]. These conditions are associated with flow disturbance, vascular remodeling, and progressive loss of vasodilator signaling [5,6]. Functional deficits in obstructive vascular disease have been linked to impaired activation of Ca2+-dependent endothelial effectors that relax vascular smooth muscle through diffusible mediators or membrane potential hyperpolarization [2,7–9]. In conduit arteries, such as carotid, femoral, and large coronary arteries, developing vascular disease is widely associated with reduced activation or decoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) availability [2,10,11]. Flow-dependent endothelial dysfunction in the microcirculation can potentiate ischemia with or without upstream arterial obstruction [12,13].

Sites of low shear stress and turbulent flow, such as arterial bifurcation points and areas proximal or distal to atherosclerotic plaques, have long been known as hotspots for intimal disruption and progressive vascular dysfunction and remodeling [14]. Early vascular pathophysiology is marked by endothelial dysfunction and transition of endothelium to a pro-inflammatory, vasoconstricting phenotype [15–17]. Vascular remodeling may involve medial layer thickening and is often characterized by migration of smooth muscle and other medial cells through the internal elastic lamina into the intima, forming a dense neointima that can progress to obstruction or even occlusion of the vessel lumen [11]. The events driving initiation and progression of low-flow vascular pathology remain poorly understood, but the degree and consistency of shear stress along the intimal wall are likely direct determinants.

While various cellular components and pathways contribute to mechanotransduction with shear stress, including mechanosensitive ion channels, G-protein coupled receptors, receptor tyrosine kinases, integrins [15,18,19], a common underlying influence is the endothelial cell Ca2+ concentration. Recent insights into physiologic Ca2+ signaling have been gleaned from studies employing high-resolution and high-speed imaging approaches and rigorous spatial and temporal analysis [20–24]. Our emerging view of Ca2+ signaling suggests that most if not all vascular beds possess a persistent profile of spatially and temporally restricted Ca2+ signals that control the degree and specificity of physiologic responses. In the endothelium, intermittent Ca2+ release events from internal endoplasmic reticulum stores via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) [22] as well as discrete events through plasma membrane transient receptor potential (TRP) channels [25,26] differentially target effectors such as Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa2.3 and 3.1) and eNOS [27], tuning the degree and specifying cell responses. Because Ca2+ regulates a wide range of effects, including membrane potential and the production and release of relaxing/constricting factors as well as apoptosis and transcription, coordinated titration and targeting of endothelial Ca2+ signals is crucial. In support of this concept, we recently provided evidence that graded agonist vasodilator responses in the arterial endothelium are tightly associated with expansion of discrete Ca2+ transients, but these responses are poorly reflected by global Ca2+ changes along the intima [26,27]. The overall implication is that spatial and temporal tuning of Ca2+ dynamics underlies many aspects of endothelial function and that chronic perturbations such as reduced laminar flow might lead to distinct dysregulation of the inherent physiologic Ca2+ signaling profiles. To date, little is known about the specific impacts of low flow on endothelial Ca2+ dynamics. Here we employ a model of chronic low flow to investigate the impact of flow disruption on functional Ca2+ signals.

Materials and methods

Partial carotid ligation and tissue harvest

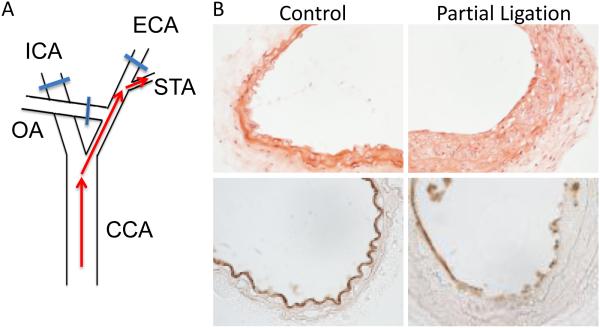

All animal procedures were approved by the University of South Alabama Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. C57BL/6 mice (10-12 weeks of age) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). The neck region was epilated with Nair and disinfected with chlorhexidine. A midline incision was made and the left carotid artery (LCA) isolated by blunt dissection. Three of the four caudal branches of the LCA (external, internal and occipital) were ligated with 6-0 silk suture, leaving the superior thyroid artery patent (Fig 1A). After closure of the incision, mice were provided normal rodent chow and water ad labitum. Both common carotid arteries (ligated and and non-ligated) were harvested 14 days post-surgery.

Figure 1.

Partial ligation of the carotid artery causes vascular wall remodeling. A. Surgical ligation procedure occludes three of four conduits of carotid artery blood flow. ICA, internal carotid artery; ECA, external carotid artery; OA, occipital artery; STA, superior thyroid artery; CCA, common carotid artery. B. H&E staining (top) shows substantial remodeling in the left proximal common carotid artery segment two weeks after ligation surgery (PL) compared to the artery that was left patent (Control). CD31 staining (bottom) shows regions of both continuous and disrupted endothelium in PL arteries.

Histology

Carotid artery segments were fixed in OCT and then cut into 7 micron cross-sections. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to visualize artery structure for morphometric assessment. CD31 staining (primary antibody with FITC secondary lable) was used to evaluate the endothelium. Digital images were collected using a Nikon 80i microscope and Nikon Elements was used to quantify medial thickness and cross-sectional wall areas (medial and neointimal) [28].

Myography

Rings from both partially ligated (PL) and control (C) carotid arteries were mounted on the wires of an isometric force myograph (Danish Myo Technology; DMT). Arteries were stretched to optimal length (determined previously via active length-tension relationships, resulting in base force of ~4mN) in bicarbonate-buffered physiological saline solution (PSS, containing in mM: 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 23 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 0.026 EDTA, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2 10.5 glucose; pH 7.45) at 37°C, gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2, and allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes. All drugs were added directly to the bath and data was recorded using Chart software at 3 hz.

Ca2+ imaging

Carotid artery segments were cut open longitudinally and mounted on sylgard blocks, intima side up, using tungsten micropins as previously described [29]. Arteries were incubated at room temperature for 40 minutes in the dark with Ca2+ indicator loading solution containing Fluo-4 AM (15 μM) and 0.06% Pluronic F-127 in HEPES-buffered PSS (containing in mM 134 NaCl, 6 KCl,1 MgCls, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose; pH 7.45). After washing and 30 minutes equilibration, blocks were placed in a glass-bottom chamber (separated 100 μm from glass by two parallel supporting pins) containing HEPES. The chamber was mounted on an inverted microscope of an Andor Revolution spinning disk confocal system. Ca2+-dependent fluorescence (488 nm excitation, 510 nm emission) was measured at 8 frames/sec at 25°C (20X objective; 1024 × 1024 pixels) using iQ software. Images were saved as 16-bit raw data during recording, and later converted into 8-bit TIFF format for offline processing. Data were processed using the custom algorithm LC_Pro [20], implemented as a plug-in with ImageJ software. This analysis software is specifically designed to: 1) detect sites of dynamic Ca2+ change above statistical (p < 0.01) noise, 2) define regions of interest (ROI; 10 pixel or 3.4 μm diameter) at active sites centers, and 3) analyze average fluorescence intensities at ROIs to determine specific event parameters. Fluorescence data are expressed as F/F0, where F0 is determined by a linear regression of base data at each ROI.

Reagents and solutions

All reagents and drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fluo-4 AM was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and CD31 primary antibody was from Abcam, Cambridge, UK. Tungsten wires (for making tiny pins) were purchased from Scientific Instrument Services (Ringoes, NJ).

Data Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error and statistical analysis performed with GraphPad Prism software. For multiple-set analysis, two-way ANOVA was performed followed by individual comparisons via Tukey post-tests. For non-Gaussian event parameters, distributions were analyzed via Kruskal-Wallis test and subsequent comparisons performed using a Dunns post-test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Two weeks of disrupted carotid artery flow causes vascular remodeling and endothelial disruption

We assessed the impact of sustained low flow on vascular structure, function and endothelial signaling using a partial carotid artery ligation mouse model as previously described [17]. In this model, left carotid artery flow was restricted by ~90% by suturing closed three of the four outflow conduit branches while the right carotid arteries were left patent to serve as controls. Two weeks post-surgery, proximal segments of the partially ligated (PL) and control (C) arteries were excised and evaluated. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of carotid artery cross-sections revealed substantial vascular wall remodeling in PL arteries compared to control right carotid arteries from the same animals (Fig 1B). This remodeling was characterized by nominal medial thickening and considerable neointimal growth (intima/media ratio = 0.43 ± 0.13). CD-31 staining of the intima indicated intermittent regions of discontinuous endothelium in PL arteries.

Chronic low flow alters vasoconstriction in response to KCl and phenylephrine

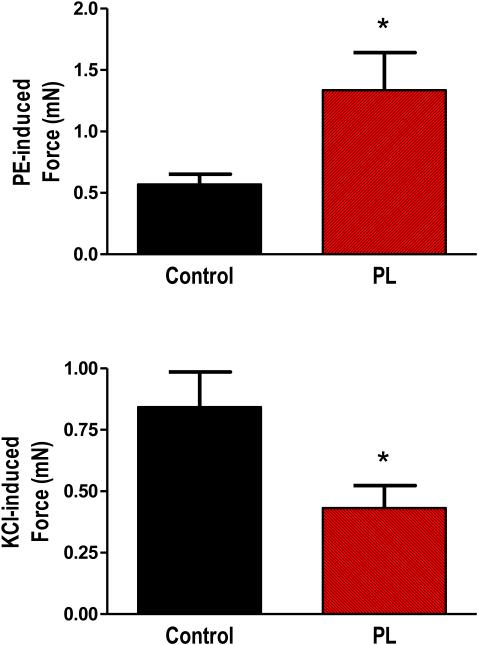

In order to assess the general contractile function of carotid arteries subjected to chronic low flow, we performed myography using isolated vessel segments. As shown in Figure 2, stimulation with the α-adrenergic receptor agonist phenylephrine (1 μM) caused significantly larger contraction in PL vessels verses controls. However, direct depolarization of vascular smooth muscle with 60 mM KCl caused smaller contractions in PL verses control arteries.

Figure 2.

Contractile function of carotid arteries following two weeks of low blood flow. Following partial ligation surgery, control and PL carotid arteries were removed and contractile function assessed using wire myography. Bar graphs show responses to 1 μM phenylephrine (PE) and 60 mM KCl. * indicates p < 0.05, n=10-11.

Endothelium-dependent relaxation is significantly blunted in arteries subjected to chronic low flow

Next, we determined whether chronic low flow altered endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. The muscarinic agonist acetylcholine (ACh) elicited concentration-dependent (10−8 - 10−5 M) relaxation of PE-contracted carotid arteries, and this relaxation was considerably blunted in PL arteries verses controls at all ACh concentrations (Fig 3).ACh relaxation of carotid arteries is mediated largely by Ca2+-dependent stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and subsequent diffusion of NO to underlying smooth muscle. Inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) with 200 μM N-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA) completely blocked Ach relaxation. In fact, in the presence of L-NNA, ACh caused modest contractions in both PL and C arteries (6.4 ± 3.9 % and 5.0 ± 0.7 %, respectively), indicating vasorelaxation in both control and PL arteries is NO dependent and blockade of endothelial NO production unmasks direct constrictor action of ACh on smooth muscle muscarinic receptors. Finally, the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10 μM) evoked complete relaxation of PE-contracted PL and C arteries (116 ± 6 % and 98 ± 10 %, respectively), confirming that the vascular smooth muscle of both control and PL arteries remained responsive to NO.

Figure 3.

Acetylcholine-induced relaxation of carotid arteries following two weeks of low blood flow. Concentration-dependent responses to the endothelium dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (ACh) was assessed in phenylephrine-precontracted control and PL carotid arteries isolated from mice two weeks after partial ligation surgery. Experiments were conducted in the absence or presence of L-NNA (n=9).

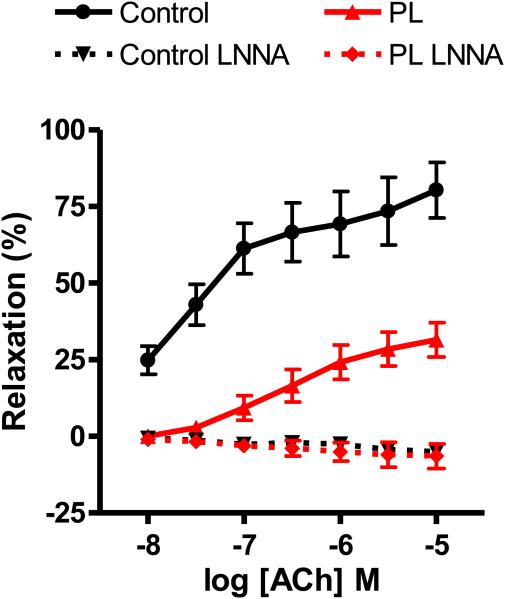

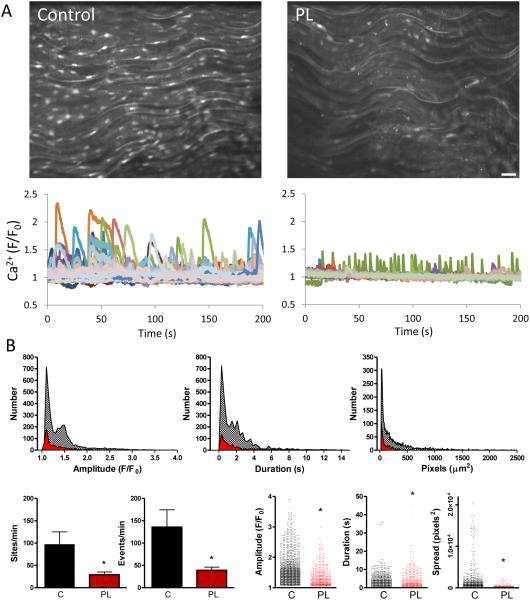

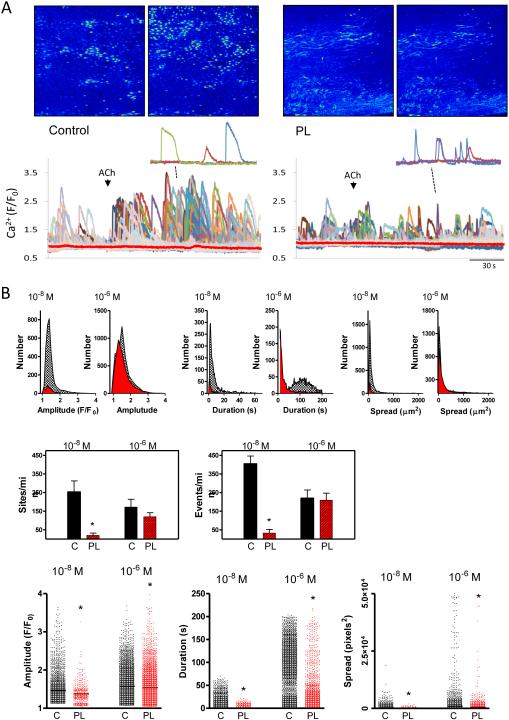

Basal and ACh-induced Ca2+ dynamics are substantially restricted in arteries exposed to chronic low flow

In order to directly examine discrete endothelial Ca2+ signals and their possible impairment in PL vessels, we performed confocal imaging in open carotid arteries loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM. Basal Ca2+ dynamics were observed along the intima of both control and PL arteries, with PL arteries exhibiting fewer and smaller events (Fig 4). This included a reduction in both the number of discrete Ca2+ mobilizing sites and total Ca2+ events per minute as well as a blunting of event amplitude, duration and spatial spread compared to controls. Addition of ACh caused distinct expansion of endothelial Ca2+ dynamics (Fig 5) in PL and control arteries. Control arteries exhibited discernable Ca2+ responses to a low ACh concentration (10−8 M) and all signal parameters including sites, events, amplitude, duration and spatial spread were significantly higher than matched PL arteries. In contrast, average Ca2+ over the whole endothelial field (Fig 5A; red lines) exhibited little or no change after this ACh exposure in either control or PL vessels. At 10−6 M ACh, Ca2+ dynamics expanded in both PL and control arteries. Under this condition, sites and events were comparable between control and PL arteries, but individual event parameters, including amplitude, duration and spread all remained higher in control arteries compared to PL arteries.

Figure 4.

Basal endothelial Ca2+ dynamics in carotid arteries following two weeks of low blood flow. A. Confocal images show Ca2+ signals of Fluo-4 AM-loaded endothelium of opened control and PL carotid arteries from a single mouse, two weeks post partial ligation surgery; maximal intensity projections from 200-second time course are shown. Bar is 20 μm. Recordings show Ca2+ dynamics occurring basally in control and PL arteries: 9 μm2 regions of interest were positioned on spatial event centers by the custom analysis algorithm LC_Pro. B. Summary of Ca2+ analysis, showing histograms and composite plots of Ca2+ parameters. This includes the number of distinct Ca2+ sites and events as well as specific event properties (amplitude, duration and spatial spread) in control (black) and PL (red) arteries. * indicates p < 0.05 verses control; n=7 for each group.

Figure 5.

Acetylcholine-induced changes in endothelial Ca2+ dynamics following two weeks of low blood flow. A. Images show maximal projections of Fluo-4 AM dependent fluorescence in the endothelium of control and PL carotid arteries before and after addition of ACh (10−8 M); For clarity, insets show (~60-second) tracings from three active sites after ACh addition in control and PL arteries. The red lines depict average global Ca2+-dependent fluorescence measured in the whole fields shown over the time courses indicated. B. Summary of Ca2+ dynamics analysis, showing histograms and composite plots of Ca2+ parameters at different concentrations of ACh in control (black) and PL (red) arteries. Parameters include the number of discrete Ca2+ sites and distinct events as well as individual event properties (amplitude, duration and spatial spread). * indicates p < 0.05 verses control at the same concentration; n=4 for each group.

Discussion

Recent studies have revealed the central role of dynamic Ca2+ signals in physiologic endothelial vasodilation through hyperpolarization and release of relaxing factors [21–23,25,26,30–32]. Disruption of this Ca2+ patterning may contribute to widespread endothelial dysfunction in developing and manifest vascular disease, but patterns of pathological endothelial Ca2+ signaling are poorly quantified and understood. Here we show that establishing a state of chronic low blood flow along the vessel lumen via partial artery ligation is sufficient to cause endothelial dysfunction characterized by distinct impairment of both basal and stimulated endothelial Ca2+ dynamics. A primary implication of these findings is that endothelial dysfunction common to the development and progression of multiple cardiovascular diseases, may be underpinned by discrete shifts in the spatial and temporal profile of Ca2+ signals. To our knowledge, this is the first assessment of dynamic endothelial Ca2+ signal patterning in developing vascular pathology.

The surgical partial ligation model employed in the current study effectively reduces blood flow through the left carotid artery by ~90% while cerebral perfusion is maintained by the patent right carotid and vertebral arteries [17]. This allows animals to survive without notable deficit or complicating end-organ ischemia. Previous studies employing this low-flow model in apo E-deficient mice on a high-fat diet showed development of obstructive atherosclerotic plaques within two weeks along with significant impairment of ACh responses [17], similar in magnitude to those reported here. In the current study, however, partial ligation was performed in normal wild-type C57Bl/6 mice on regular chow in order to restrict perturbation to low flow alone. Correspondingly, no plaques were formed, but the mice developed considerable neointimal growth over the two-week period. Overall, the findings suggest that acute restriction of blood flow alone, even in the absence of metabolic dysfunction and high dietary fat, is sufficient to promote endothelial dysfunction and pathologic vascular remodeling in vivo. Chronically reduced shear stress may, in fact, be the primary driving force for the observed changes, as low and oscillatory shear profiles promote endothelial transition to an inflammatory, pro-constricting phenotype associated with vascular wall remodeling [6,10]. Notably, while the current study supports a causative role for shear stress it does not rule out other possible contributors, including local inflammation from the surgical procedure itself.

We found that constrictor responses were mixed in PL carotid arteries; PE-induced contractions were enhanced while KCl contractions were reduced relative to controls. While reduced KCl contractions imply smooth muscle impairment during long-term flow disruption, histology and PE responses argue against overt loss of muscle or general contractile dysfunction. Overall, the enhanced pharmacomechanical verses electromechanical contraction suggests possible increased Ca2+ sensitization in PL artery smooth muscle. The role of the endothelium in these contractile responses is unclear, but loss of endothelial NO under chronic oscillatory, low-flow conditions may contribute. Indeed, progressive endothelial dysfunction under low shear stress is associated with reduced eNOS expression and lower NO bioavailability [10,17]. Production of NO by eNOS is Ca2+ dependent [33]. Although we observed suppressed basal Ca2+ signaling in PL artery endothelium, blockade of eNOS alone had little net effect on PL or control carotid artery tone, suggesting minimal influence of basal NO. Myoendothelial communication of IP3 (and perhaps Ca2+ itself) from smooth muscle to endothelium through myoendothelial gap junctions can elicit feedback vasorelaxation by increasing endothelial Ca2+ dynamics [32]; in PL artery endothelium, the restricted size and range of Ca2+ signals might limit this feedback control, promoting vasoconstriction. Whether the prevailing truncated endothelial Ca2+ signals promote release of constricting factors such as endothelin is unknown. Incidentally, reduced KCl contractions have been observed in vessels subjected to physical endothelial damage or removal [27,34]. The current observations of weaker KCl contractions in PL arteries could be related to similar endothelial disruption following chronic low flow although we observed that much of the endothelium (~80%) remained intact. Overall, the current implication is that two-weeks of low flow is sufficient to augment agonist-mediated tone, making affected vessels more vulnerable to local and circulating vasoconstrictors.

We found that in animals undergoing partial carotid ligation surgery, ACh-induced relaxation was substantially impaired in the carotid arteries experiencing chronic low flow compared to the patent control arteries, consistent with endothelial dysfunction. This impaired vasorelaxation occurred over a broad range of ACh concentrations and was comparable to that reported previously in carotid artery segments from atherogenic ApoE-/-, high-fat-fed mice subjected to similar surgery [17]. Although these studies were conducted under somewhat different experimental conditions (i.e. 2 and 7 days post ligation surgery) our findings suggest chronic low flow is itself a major impetus for vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction, independent of genetic metabolic dysregulation and diet. In previous studies, we showed that vasorelaxation in response to graded endothelial stimulation (e.g. via ACh or substance P) is tightly linked to the graded expansion of endothelial cell Ca2+ dynamics that were not indicated by changes in global Ca2+ levels [21,27]. This is likely due to the localized, transient, and asynchronous nature of these Ca2+ events. Here, we show that in addition to the reduced basal Ca2+ dynamics occurring along the PL artery endothelium compared to that of control arteries, expansion of Ca2+ dynamics by ACh was substantially muted (at both low and high concentrations), corresponding with the depressed vasorelaxations at these concentrations in functional studies. In fact, at 10−8 M, ACh failed to alter Ca2+ dynamics or elicit vasorelaxation in PL arteries although these responses were clearly measurable in control arteries from the same animals. Importantly, these differences in control and PL artery responses could not be readily discerned by tracking the average (global) Ca2+ signal along the endothelial field. It is important to note that the analysis logarithm (LC_Pro) applied here places distinct 9 μm2 ROI’s at autodetected centers of activity, tracking only the discrete sites of Ca2+ deflection and avoiding signal dilution over the whole field. This prevents local activity from being obscured within the tissue and underscores the utility of comprehensive spatial and temporal Ca2+ assessment in deciphering functionally relevant changes in Ca2+ signals. Both control and PL arteries responded appreciably to higher stimulation (ACh 10−6 M), with the number of Ca2+ events as well as event amplitude, duration and spatial spread all increasing. Interestingly, at this concentration, the number of distinct sites and events was essentially indistinguishable from control while event parameters (amplitude, duration and spread) all remained lower than controls. Most notably, the change in event duration was very modest in PL arteries compared to the large shift in control arteries. The findings suggest development of a new Ca2+ signal pattern in arteries exposed to low flow, characterized by frequent but small (spatially and temporally restricted) events. This shift in Ca2+ signal profile may underlie broad changes in effector recruitment portending endothelial dysfunction and the progression of vascular disease, particularly, the transition from a principal NO signaling profile to one predominated by reactive oxygen species and inflammation [35–37].

Perspective

The current study establishes the role of chronically reduced blood flow in the disruption of endothelial Ca2+ signaling dynamics and endothelial vasodilation. The primary implication is that discrete shifts in the endothelial Ca2+ signaling pattern may be an early and pivotal step in the pathologic structural and functional changes occurring in arteries under conditions of disturbed blood flow in vivo (e.g. developing coronary or peripheral artery disease). These studies also emphasize the need to assess spatial and temporal endothelial Ca2+ signals rather than simply examining global Ca2+ changes that may not reflect subtle but important pathway transitions. Subsequent studies linking endothelial Ca2+ patterning not only to functional responses but also to underlying processes of medial remodeling will provide additional insight into the overall interplay between the endothelial and smooth muscle cells during disease.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Taylor was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, award number R01 HL085887 and by S10 0D020149. Dr. Weber was supported by the R01 HL084159 and a Research and Scholarly Development Grant from the University of South Alabama Office of Research and Economic Development.

References

- 1.Bugiardini R, Manfrini O, Pizzi C, Fontana F, Morgagni G. Endothelial function predicts future development of coronary artery disease: a study of women with chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. Circulation. 2004;109:2518–2523. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128208.22378.E3. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000128208.22378.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285–1295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton M. Prevention and endothelial therapy of coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.005. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiatt WR, Armstrong EJ, Larson CJ, Brass EP. Pathogenesis of the limb manifestations and exercise limitations in peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1527–1539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto K, Ando J. New Molecular Mechanisms for Cardiovascular Disease: Blood Flow Sensing Mechanism in Vascular Endothelial Cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2011;116:323–331. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10r29fm. doi:10.1254/jphs.10R29FM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiu J-J, Chien S. Effects of Disturbed Flow on Vascular Endothelium: Pathophysiological Basis and Clinical Perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:327–387. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2009. doi:10.1152/physrev.00047.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Role of Endothelial Shear Stress in the Natural History of Coronary Atherosclerosis and Vascular Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2379–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra RJ, Brotherton AF, Goodwin PJ, Clark CR, Armstrong ML, Harrison DG. Mechanisms of abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in atherosclerosis: implications for altered autocrine and paracrine functions of EDRF. Blood Vessels. 1989;26:300–314. doi: 10.1159/000158779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luksha L, Agewall S, Kublickiene K. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in vascular physiology and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:330–344. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng C. Shear stress affects the intracellular distribution of eNOS: direct demonstration by a novel in vivo technique. Blood. 2005;106:3691–3698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2326. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cayatte AJ, Palacino JJ, Horten K, Cohen RA. Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide production accelerates neointima formation and impairs endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb J Vasc Biol Am Heart Assoc. 1994;14:753–759. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller-Delp JM. The Coronary Microcirculation in Health and Disease. ISRN Physiol. 2013;2013:1–24. doi:10.1155/2013/238979. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kothawade K, Bairey Merz CN. Microvascular Coronary Dysfunction in Women—Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2011;36:291–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2011.05.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku DN, Giddens DP, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1985;5:293–302. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.5.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Li Y-S, Chien S. Shear Stress-Initiated Signaling and Its Regulation of Endothelial Function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2191–2198. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303422. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorescu GP, Sykes M, Weiss D, Platt MO, Saha A, Hwang J, et al. Bone Morphogenic Protein 4 Produced in Endothelial Cells by Oscillatory Shear Stress Stimulates an Inflammatory Response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31128–31135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300703200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nam D, Ni C-W, Rezvan A, Suo J, Budzyn K, Llanos A, et al. Partial carotid ligation is a model of acutely induced disturbed flow, leading to rapid endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. AJP Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1535–H1543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00510.2009. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00510.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando J, Yamamoto K. Vascular mechanobiology endothelial cell responses to fluid shear stress. Circ J. 2009;73:1983–1992. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ando J, Yamamoto K. Effects of shear stress and stretch on endothelial function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1389–1403. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis M, Qian X, Charbel C, Ledoux J, Parker JC, Taylor MS. Automated region of interest analysis of dynamic Ca(2)+ signals in image sequences. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C236–243. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2012. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian X, Francis M, Kohler R, Solodushko V, Lin M, Taylor MS. Positive feedback regulation of agonist-stimulated endothelial Ca2+ dynamics by KCa3.1 channels in mouse mesenteric arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:127–135. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302506. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledoux J, Taylor MS, Bonev AD, Hannah RM, Solodushko V, Shui B, et al. Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9627–9632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801963105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801963105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kansui Y, Garland CJ, Dora KA. Enhanced spontaneous Ca2+ events in endothelial cells reflect signalling through myoendothelial gap junctions in pressurized mesenteric arteries. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.012. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan MN, Francis M, Pitts NL, Taylor MS, Earley S. Optical recording reveals novel properties of GSK1016790A-induced vanilloid transient receptor potential channel TRPV4 activity in primary human endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:464–472. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078584. doi:10.1124/mol.112.078584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, et al. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science. 2012;336 doi: 10.1126/science.1216283. doi:10.1126/science.1216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian X, Francis M, Solodushko V, Earley S, Taylor MS. Recruitment of dynamic endothelial Ca2+ signals by the TRPA1 channel activator AITC in rat cerebral arteries. Microcirc N Y N 1994. 2013;20:138–148. doi: 10.1111/micc.12004. doi:10.1111/micc.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis M, Waldrup JR, Qian X, Solodushko V, Meriwether J, Taylor MS. Functional tuning of intrinsic endothelial Ca2+ dynamics in swine coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2016;118:1078–1090. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manogue MR, Bennett JR, Holland DS, Choi C-S, Drake DA, Taylor MS, et al. Smooth Muscle Specific Overexpression of p22 phox Potentiates Carotid Artery Wall Thickening in Response to Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2015/305686. doi:10.1155/2015/305686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francis M, Waldrup J, Qian X, Taylor MS. Automated Analysis of Dynamic Ca<sup>2+</sup> Signals in Image Sequences. J Vis Exp. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51560. doi:10.3791/51560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dora KA, Garland CJ. Linking hyperpolarization to endothelial cell calcium events in arterioles. Microcirc N Y N 1994. 2013;20:248–256. doi: 10.1111/micc.12041. doi:10.1111/micc.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boerman EM, Everhart JE, Segal SS. Advanced age decreases local calcium signaling in endothelium of mouse mesenteric arteries in vivo. Am J Physiol - Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H1091–H1096. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00038.2016. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00038.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran CHT, Taylor MS, Plane F, Nagaraja S, Tsoukias NM, Solodushko V, et al. Endothelial Ca2+ wavelets and the induction of myoendothelial feedback. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1226–1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2011. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michel JB, Feron O, Sacks D, Michel T. Reciprocal regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by Ca2+-calmodulin and caveolin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15583–15586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lippolis L, Sorrentino R, Popolo A, Maffia P, Nasti C, d’Emmanuele di Villa Bianca R, et al. Time course of vascular reactivity to contracting and relaxing agents after endothelial denudation by balloon angioplasty in rat carotid artery. Atherosclerosis. 2003;171:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan Y, Wei C, Zhang W, Cheng H, Liu J. Cross-talk between calcium and reactive oxygen species signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:821–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00390.x. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Bubolz AH, Mendoza S, Zhang DX, Gutterman DD. H2O2 is the transferrable factor mediating flow-induced dilation in human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2011;108:566–573. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237636. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goncharov NV, Avdonin PV, Nadeev AD, Zharkikh IL, Jenkins RO. Reactive oxygen species in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:1134–1146. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666141014142557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]