Abstract

Blood flow into the brain is dynamically regulated to satisfy the changing metabolic requirements of neurons, but how this is accomplished has remained unclear. Here, we demonstrate a central role for capillary endothelial cells in sensing neural activity and communicating it to upstream arterioles in the form of an electrical vasodilatory signal. We further demonstrate that this signal is initiated by extracellular potassium (K+)—a byproduct of neural activity—which activates capillary endothelial cell inward-rectifier K+ (KIR2.1) channels to produce a rapidly propagating retrograde hyperpolarization that causes upstream arteriolar dilation, increasing blood flow into the capillary bed. Our results establish brain capillaries as an active sensory web that converts changes in external K+ into rapid, ‘inside-out’ electrical signaling to direct blood flow to active brain regions.

Keywords: Inward-rectifier potassium channel, calcium-activated potassium channels, capillary endothelium, K+ signaling, cerebral blood flow, functional hyperemia, neurovascular coupling

Neurons lack substantial energy reserves and thus rely on an on-demand system for the delivery of blood-borne nutrients. The crux of this system is a process termed neurovascular coupling (NVC), which translates neural activity into a rapid increase in local blood flow (“functional hyperemia”) by causing dilation of penetrating (parenchymal) arterioles and surface (pial) arteries1. To serve its on-demand function, this mechanism must be capable of fast, long-distance transmission of vasodilator signals from deep within the cortex to the brain’s surface2. However, how neural activity is sensed by and transmitted from the microcirculation is not known.

It is generally accepted that NVC involves the release of vasodilator substances from neurons and/or astrocytes, and it has been proposed that the smooth muscle (SM) of parenchymal arterioles is a target of such vasoactive compounds3. Parenchymal arterioles supply blood to discrete regions of the cortex4, but their limited spatial coverage of the brain precludes their direct communication with the vast majority of neurons. By contrast, every neuron is closely apposed to endothelial cells (ECs) of the extensive, anastomosing network of brain capillaries5. This uniquely positions capillary ECs (cECs) to act as sensors of local neuronal activity throughout the brain. Nonetheless, cECs have not been viewed as active participants in NVC.

By postulating electrical coupling between brain cECs as reported for systemic arteriolar ECs6, it is possible to envision a mechanism in which the continuous, interconnected capillary network acts like a system of “wires” to communicate electrical signals to upstream parenchymal arterioles, and ultimately to pial arteries. In contrast to axonal electrical communication, which takes the form of a propagating membrane potential depolarization, this would involve transmission of a hyperpolarizing signal from cECs to ECs in upstream arterioles and surface arteries. The subsequent spread of this hyperpolarization to adjacent SM through gap junctions at myoendothelial projections7 would then hyperpolarize the SM, deactivating voltage-dependent calcium (Ca2+) channels, diminishing Ca2+ influx and reducing Ca2+-dependent actin-myosin cross-bridge cycling, resulting in arterial/arteriolar dilation8.

An important molecular requirement for such signaling is an ion channel whose activation enables regeneration of current over long distances. K+ channels of the KIR2 family are perfectly suited to act as EC sensors of neural activity: they are activated by external K+, which accumulates during neural activity9, and the resultant increase in their K+ conductance can be regenerated in neighboring cells by virtue of the steep activation of these channels by hyperpolarization10–12. Because endothelial cells have a depolarized resting membrane potential (approximately −40 mV)13, and the K+ equilibrium potential (EK) is very negative (approximately −103 mV in cerebrospinal fluid), increases in capillary KIR channel conductance in response to an elevation of K+ to less than ~25 mM would cause membrane potential hyperpolarization towards the new EK. This hyperpolarizing current would then be transmitted through gap junctions to the adjacent cEC, activating resident KIR channels and thereby regenerating the hyperpolarizing current. Despite the intrinsic appeal of this concept, little is known regarding the ion channel repertoire of cECs or their role in regulating cerebral blood flow (CBF).

Here, we demonstrate that brain capillaries act as a sensory web to coordinately and dynamically translate neural activity within the brain parenchyma into an increase in local blood flow, establishing brain capillaries as a central element in the NVC process.

RESULTS

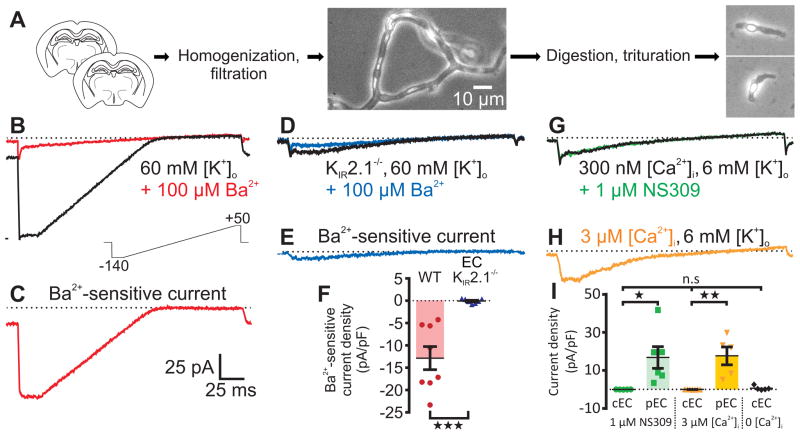

Brain cECs express KIR2 channels: functional K+ sensors

Using a mechanical and enzymatic dissociation approach, we acutely isolated mouse brain cECs for electrophysiological analyses of their ion channel profile (Fig. 1a). To facilitate detection of KIR channels, we raised external [K+]o to 60 mM and measured whole-cell currents in response to 200-ms voltage ramps from −140 to +50 mV. Pronounced inward currents were detected at potentials negative to the K+ equilibrium potential (EK; −23 mV), whereas at potentials positive to EK the current rectified dramatically (Fig. 1b). Barium (Ba2+), a selective pore-blocker of KIR2 channels at concentrations less than 100 μM10, eliminated this current (Fig. 1b). Accordingly, Ba2+-sensitive traces revealed a current signature characteristic of the strong inward-rectifier KIR2 channel family10,14 (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Capillary ECs possess functional KIR channels, but lack SK and IK channels. (A) Overview of cell isolation. Left to right: Two brain slices were homogenized then filtered to yield branching capillaries. Extracellular matrix was enzymatically removed and capillaries were triturated to yield single cells. Scale bar applies to all micrographs. (B) With 60 mM [K+]o to increase KIR conductance, a 200-ms voltage ramp from −140 to +50 mV (lower inset) generated whole-cell currents (black trace) with a large inward component at hyperpolarized potentials. Superfusion of 100 μM Ba2+ (red trace) eliminated evoked currents. (C) Subtracted 100 μM Ba2+-sensitive currents reveal a classic strongly rectifying K+ current. (D) 100 μM Ba2+ (blue) was without effect on capillary ECs from EC KIR2.1−/− mice. (E) Subtracted 100 μM Ba2+-sensitive current from the KIR2.1−/− capillary EC in D. (F) Comparison of Ba2+-sensitive capillary EC current density at −140 mV in WT C57BL/6 (n = 8 cells, 8 mice) and EC KIR2.1−/− (n = 7 cells, 7 mice) mice (***P = 0.0005 (t13 = 4.587) unpaired Student’s t-test). (G) With 6 mM [K+]o and 300 nM [Ca2+]i, 1 μM NS309 had no effect on capillary EC currents. (H) Dialyzing with 3 μM Ca2+ did not affect membrane currents. (I) Summary data at 0 mV. NS309 (1 μM) had no effect on capillary ECs (cEC; n = 5 cells, 3 mice), but evoked large currents in control pial ECs (pEC; n = 6 cells, 4 mice; *P = 0.0253 (t9 = 2.678) unpaired Student’s t-test). Currents were absent in capillary ECs dialyzed with 3 μM [Ca2+]i (n = 7 cells, 2 mice), in contrast to pial ECs, which developed prominent K+ currents upon dialysis of 3 μM Ca2+ (n = 5 cells, 4 mice; **P = 0.0011 (t10 = 4.548) unpaired Student’s t-test). Dialysis with a solution containing 0 Ca2+ and 5 mM EGTA had no effect on capillary EC currents compared with cells dialyzed with 300 nM or 3 μM Ca2+ (n = 5 cells from 2 mice; P = 0.251 (FDFn,DFd = 1.5282,14) one-way ANOVA). All error bars represent s.e.m.

Functional KIR2 channels are homo- or heterotetrameric assemblies of KIR2.1–2.3 subunits15. In the cerebral circulation, the KIR2.1 subunit (encoded by the Kcnj2 gene) is an essential component of native SM KIR channels16. To test whether this is also true for cECs, we used a Cre-lox strategy to generate an EC-specific KIR2.1-knockout (EC KIR2.1−/−) mouse17,18 and examined its cEC KIR current properties. In contrast to cells from wild-type (WT) mice, all of which displayed KIR currents, none of the examined cECs from EC KIR2.1−/− mice possessed Ba2+-sensitive currents (Fig. 1, d–f). A quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis confirmed that Kcnj2 gene transcripts were dramatically reduced in brain cECs from these mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also found that KIR currents in pial artery SM cells (Supplementary Fig. 2) were unchanged compared with those in WT mice, confirming EC-specific KIR knockout. Additional control experiments showed that cEC KIR currents were not disrupted by the presence of loxP sites flanking the Kcnj2 gene (KIR2.1fl/fl mice) or by Cre recombinase expression in the endothelium (Tek-Cre mice; Supplementary Table 1). These data indicate that KIR2.1 is a critical component of functional KIR channels in brain cECs and establish the validity of our EC KIR2.1−/− mouse model.

Ca2+-activated SK and IK channels are not expressed in brain cECs

Without exception, ECs in all arteries and arterioles studied to date possess small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (SK and IK, respectively)19, which transduce changes in intracellular Ca2+ into membrane hyperpolarization. Contrary to expectations, we found no evidence for either of these channels in cECs. With 300 nM intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) in the patch pipette, a saturating concentration (1 μM) of the synthetic, selective SK/IK channel agonist NS309 (EC50 ≈ 10 nM)20 did not affect cEC currents (Fig. 1g), but did evoke robust SK/IK channel activation in pial artery ECs (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Next, we attempted to stimulate Ca2+-sensitive currents in cECs directly by setting the pipette (intracellular) [Ca2+] to 3 μM. This maneuver produced large K+ currents (nearly identical to those evoked by NS309) in pial ECs (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 3b), but did not change membrane currents in cECs (Fig. 1h,i). Dialysis of cECs with a solution designed to buffer [Ca2+]i to very low levels also had no effect on currents (Fig. 1i). These data indicate that cECs lack functional SK and IK channels and, more broadly, entirely lack Ca2+-activated ion channels in the plasma membrane.

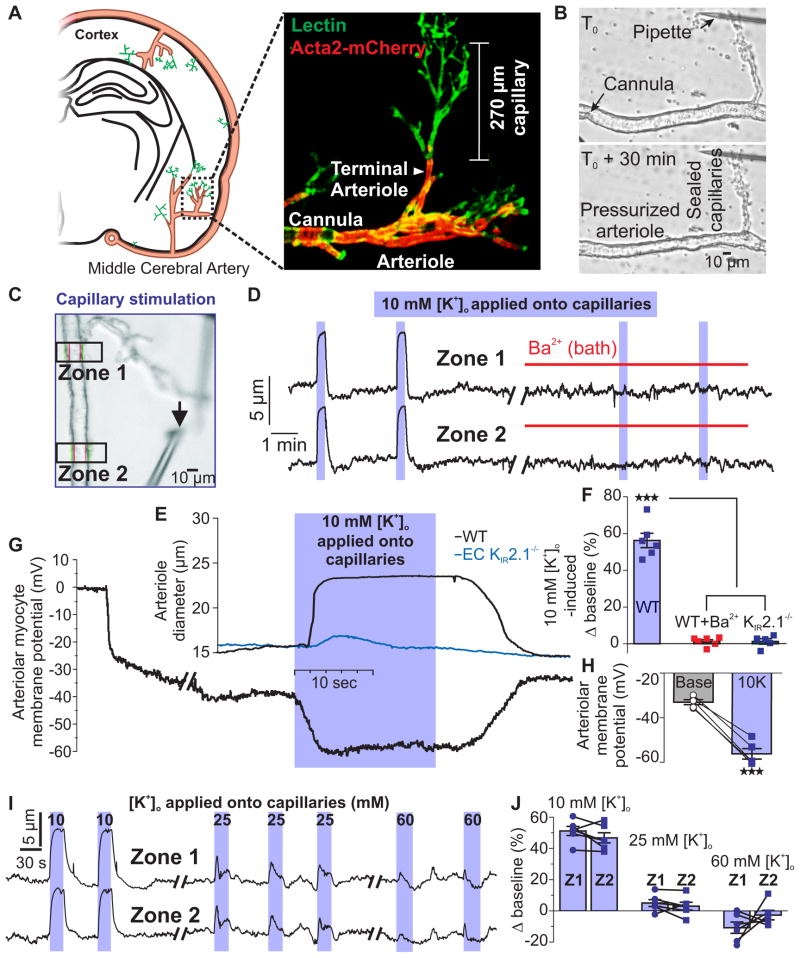

Capillaries translate local elevations of K+ into upstream arteriolar dilations

Expression of functional KIR2.1 channels endows cECs with the ability to detect and respond to increases in external K+ with membrane hyperpolarization10. To test whether K+ activation of KIR channels in cECs can dilate upstream arterioles, we developed a novel ex vivo preparation. An extension of our well-established approach using isolated parenchymal arterioles from mice21–23, this CaPA (capillary-parenchymal arteriole) preparation consists of a cannulated parenchymal arteriole segment with an intact, downstream capillary tree held in place with an overlying micropipette that occludes and stabilizes its extremities (Fig. 2a,b). Responses of the arteriolar segment to pressure and bath application of vasodilators (NS309, 10 mM K+) or constrictor agonists (U46619) were the same in both isolated parenchymal arterioles and CaPA preparations (Supplementary Fig. 4). An important advantage of the CaPA preparation is that it allows vasoactive agents to be directly and selectively applied onto terminal ends of the capillaries or onto the arteriole without producing confounding effects on other cell types in the brain.

Fig. 2.

Application of K+ to capillaries causes rapid upstream parenchymal arteriole dilation ex vivo. (A) Left: CaPA preparations were obtained from the middle cerebral artery region. Right: Typical CaPA preparation from an Acta2 GCaMP5-mCherry mouse (see Online Methods) showing SM (red) giving way to branching capillaries (lectin; green). Each CaPA preparation consists of an arteriole segment (320 μm ± 14 μm long, n = 16) and a capillary tree composed of one first-order branch (168 ± 12 μm long) with an average of 4 ± 1 second-order branches (100 ± 8 μm long). (B) Constriction of the arteriole to 40 mm Hg in a CaPA preparation. (C) Pipette position for capillary stimulation by pressure ejection. Black arrow indicates the tip of the pipette. Diameter was simultaneously recorded in two zones (boxes). The average distance from the capillary stimulation site to Zone 1 was 226 ± 19 μm. (D) Arteriolar diameter at Zone 1 and Zone 2 in a CaPA preparation. Application of 10 mM K+ (5 psi) to capillaries produced rapid upstream arteriolar dilation, which was blocked by 30 μM Ba2+. (E) Expanded trace showing parenchymal arteriole dilation at Zone 2 to capillary stimulation with 10 mM K+ for 18 s in preparations from WT C57BL/6 (black trace) and EC KIR2.1−/− (blue trace) mice. (F) Summary data showing diameter changes in Zone 2 induced by 10 mM K+ applied directly onto capillaries in WT preparations (n = 6 preparations, 6 mice) before and after 30 μM Ba2+ and in EC KIR2.1−/− preparations (n = 5 preparations, 5 mice; ***P < 0.0001, (FDFn,DFd = 154.82,14) one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (G) Membrane potential of SM cells at Zone 2 in a pressurized (40 mm Hg) arteriolar segment during application of 10 mM K+ onto capillaries. (H) Summary data showing membrane potential before and after application of 10 mM K+ for 18 s to capillaries (n = 5 preparations, 5 mice; ***P = 0.0002, (t4 = 12.94) paired Student’s t-test). (I) Effects of capillary application of 10, 25, and 60 mM external K+ on arteriolar diameter at Zone 1 and Zone 2. (J) Summary data showing diameter changes in Zone 1 and Zone 2 induced by 10, 25, and 60 mM K+ applied directly onto capillaries. Responses to 25 and 60 mM K+ compared to baseline diameter and between Zone 1 and Zone 2 were not significantly different (n = 6 preparations, 6 mice; baseline vs 25 mM K+: P = 0.1128, (t5 = 1.921); baseline vs 60 mM K+: P = 0.4984, (t5 = 0.7296); Zone 1 vs Zone 2: P = 0.3908, (t5 = 0.9390) at 25 mM K+, and P = 0.2580, (t5 = 1.276) at 60 mM K+, paired Student’s t-test). All error bars represent s.e.m.

Using this approach, we selectively stimulated capillaries (or arterioles) with agents and measured arteriolar diameter at two zones ~200 μm apart (Fig. 2c). Application of 10 mM K+ to capillary extremities produced a rapid and reproducible dilation of the upstream arteriole in both zones (Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Movie 1). Consistent with our hypothesis, arteriolar dilation to capillary-applied 10 mM K+ was prevented by pretreatment with 30 μM Ba2+ (Fig. 2d,f) and was eliminated in EC KIR2.1−/− mice (Fig. 2e,f). We also tested whether upstream arterioles dilated to lower concentrations (6–9 mM) of capillary-applied K+. These experiments revealed a threshold for activation between 6 and 7 mM K+, followed by graded responses to concentrations between 7 and 10 mM (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In control experiments, pressure ejection of the IK/SK agonist, NS309 (1 μM), onto capillary extremities ~280 μm distant from Zone 1 had no effect on upstream arteriole diameter (Supplementary Fig. 6), consistent with the lack of functional SK and IK channels in cECs (Fig. 1g–i). As expected, delivery of NS309 through a pipette positioned directly adjacent to the arteriole produced robust dilation through activation of arteriolar EC SK and IK channels (Supplementary Fig. 6)24. These observations illustrate that compounds delivered onto capillaries in this preparation do not inadvertently stimulate the upstream arteriole. Parenchymal arterioles from EC KIR2.1−/− mice exhibited normal myogenic tone and vasodilatory responses to direct delivery of 1 μM NS309 (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating that vasomotor function and endothelial communication to the arteriolar SM remained intact despite the loss of functional EC KIR channels. Upstream arteriole dilation to capillary-applied K+ was also retained in KIR2.1fl/fl mice and Tek-Cre mice (Supplementary Table 1), confirming that the absence of K+-induced upstream arteriolar dilation is not an artifactual consequence of the presence of floxed-KIR2.1 or Tek-Cre cassettes.

Elevation of K+ around capillaries evokes retrograde electrical signaling to the SM of upstream arterioles

Activation of K+ channels in parenchymal arteriole ECs generates hyperpolarization that is transferred to the SM via myoendothelial gap junctions24. To test the hypothesis that K+-mediated dilation in our CaPA preparation reflects the propagation of a hyperpolarizing signal from capillaries, we measured the SM cell membrane potential at Zone 2, ~500 μm from the site of capillary stimulation (Fig. 2c). Application of 10 mM K+ onto capillaries caused a reversible −23.2 ± 1.8 mV hyperpolarization with an onset latency of 0.24 ± 0.03 s (Fig. 2c,g,h). Previous analyses of membrane potential-diameter relationships in pial arteries and parenchymal arterioles25,26 indicate that membrane potential hyperpolarization to about −56 mV should cause near maximal dilation—exactly as we observed (Fig. 2,e–h). Collectively, the brief latency to hyperpolarization, which is compatible with electrical transmission, and control experiments showing that capillary-applied agents do not inadvertently come in direct contact with the upstream arteriolar segment (Supplementary Fig. 6), compel the conclusion that brain cECs are electrically coupled, as supported by previous studies on peripheral cECs6. This conclusion is further buttressed by the observation that responses to capillary-applied agents are lost if the physical integrity of the CaPA preparation is disrupted by severing the capillary segment at the arteriole junction (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, our data support the concept that brain capillary KIR channels act as K+ sensors to initiate a retrograde hyperpolarization that is rapidly transmitted through the endothelium to upstream parenchymal arteriolar SM to cause vasodilation.

In contrast to 10 mM K+, neither 25 nor 60 mM K+ caused a sustained upstream dilation (Fig. 2i,j), indicating that K+ concentrations > 25 mM do not cause membrane potential hyperpolarization10,26. Since direct application of K+ > 25 mM causes sustained membrane potential depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries21,26,27, the absence of a constrictor response to 25 or 60 mM K+ further confirms that substances pressure ejected onto capillaries do not inadvertently stimulate the upstream arteriole and indicates that capillaries lack the ion channels required to generate regenerative depolarizing currents. Collectively, these results imply that retrograde vasodilatory signaling will be short-circuited in cases of substantially elevated external K+, as occurs in certain pathological settings, such as cortical spreading depression and ischemia28.

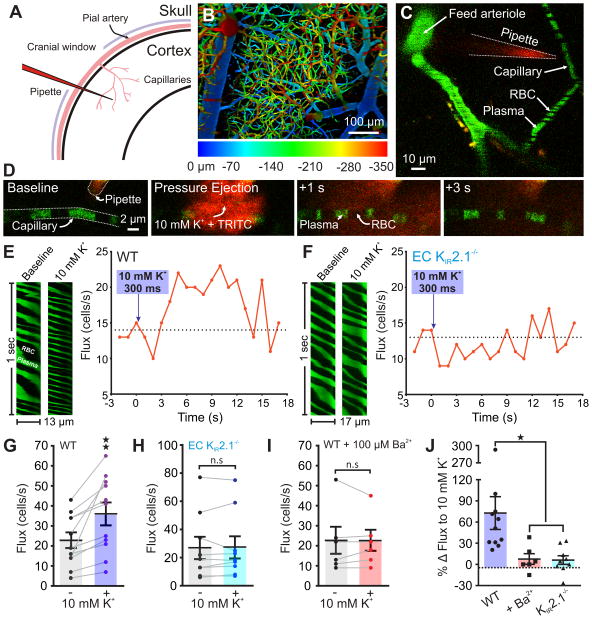

Raising K+ around capillaries in vivo evokes upstream arteriolar dilation and capillary hyperemia

To extend these observations in vivo, we tested whether capillary KIR channel-mediated retrograde electrical communication dilates upstream arterioles to deliver more blood into the capillary bed. We stimulated brain capillary segments in situ with K+ and recorded either upstream arteriolar diameter or capillary red blood cell (RBC) flux and velocity through a cranial window using two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (Fig. 3a). To visualize the arteriolar-capillary network in vivo (Fig. 3b) and enable contrast imaging of RBCs, we introduced fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran into the circulation of anesthetized mice. We then positioned a pipette containing 10 mM K+ adjacent to a post-arteriolar capillary (130 ± 15 μm downstream of the feed arteriole; n = 22; Fig. 3c) and raised local K+ by pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ for 200–300 ms (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Movie 2). This maneuver caused a rapid (latency, 3.8 ± 0.9 s; n = 11) and robust increase in RBC flux (73% ± 23%; n = 11; Fig. 3e,g,j) and velocity (Supplementary Fig. 9a,e). These effects were not observed following ejection of a 3 mM K+ solution (Supplementary Fig. 10), precluding a mechanical mechanism. Inhibiting neuronal activity by cranial-surface application of tetrodotoxin (3 μM), a voltage-dependent Na+ channel blocker, did not attenuate K+-induced increases in RBC flux or velocity (Supplementary Fig. 11), also ruling out a coupling mechanism involving direct neuronal stimulation. The specific involvement of EC KIR channels in these in vivo actions of applied K+ was examined by measuring hyperemic responses to K+ in the presence of Ba2+ and in EC KIR2.1−/− mice. Application of 10 mM K+ onto capillaries of EC KIR2.1−/− mice failed to increase RBC flux or velocity (Fig. 3f,h,j and Supplementary Fig. 9b,f), supporting the central role of EC KIR2.1 channels in K+-induced retrograde signaling and capillary hyperemia. Furthermore, 10 mM K+ did not change capillary RBC velocity or flux in WT mice in the presence of 100 μM Ba2+ (Fig. 3i,j and Supplementary Fig. 9c,d,g). Together, these data indicate that increases in external K+ drive KIR channel-mediated retrograde capillary-to-arteriole communication in vivo through activation of EC KIR2.1 channels (Fig. 3j).

Fig. 3.

K+ causes capillary hyperemia in vivo through KIR2.1 channel activation. (A) Experimental paradigm. Mice were injected with FITC-dextran, then equipped with a cranial window through which the cerebral circulation was visualized using 2-photon laser-scanning microscopy (2PLSM). (B) Depth-coded micrograph of an area of the cortical vasculature. Capillaries downstream of penetrating parenchymal arterioles were identified for further analysis. (C) A pipette containing aCSF with 3 or 10 mM K+ plus TRITC-dextran was introduced next to a capillary, which was then line-scanned at 5 kHz during local pressure ejection of the pipette contents. (D) Micrographs depicting (left to right) the evolution of TRITC diffusion (red) after pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ (200 ms, 4 psi) onto a capillary (green). The brevity and low pressure of the ejection conditions ensured that K+ remained local. (E) Left: Baseline and peak distance-time plots of capillary line scans showing hyperemia to the ejection of 10 mM K+ onto a capillary. RBCs passing through the line-scanned capillary appear as black shadows against green fluorescent plasma. Right: Typical experimental time-course for a WT mouse showing RBC flux binned at 1-s intervals before and after pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ (300 ms, 8 psi; purple arrow) onto a capillary, demonstrating hyperemia to K+ delivery. (F) Left: Line scan plots for an experiment in which 10 mM K+ was pressure ejected onto a capillary in an EC KIR2.1−/− mouse, illustrating an absence of hyperemia to this maneuver. Right: Typical flux-time trace for an EC KIR2.1−/− mouse capillary. Pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ (300 ms, 8 psi; purple arrow) did not evoke hyperemia. (G) Summary RBC flux responses to 10 mM K+ in WT mice. K+ delivery caused significant hyperemia (n = 11 paired experiments, 11 mice; **P = 0.0038 (t10 = 3.75) paired Student’s t-test). (H) Summary data for EC KIR2.1−/− mice (n = 9 paired experiments, 9 mice). 10 mM K+ did not evoke hyperemia (P = 0.8265 (t8 = 0.2265) paired Student’s t-test). (I) Ba2+ (100 μM), applied to the cranial surface, inhibited capillary hyperemia to 10 mM K+ (n = 6 paired experiments, 6 mice; P > 0.99 (t5 = 0) paired Student’s t-test). (J) Change in RBC flux expressed as a percentage of baseline for each experimental group (*P = 0.016 vs. WT, FDFn,DFd = 4.9742,23, one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison test). All error bars represent s.e.m.

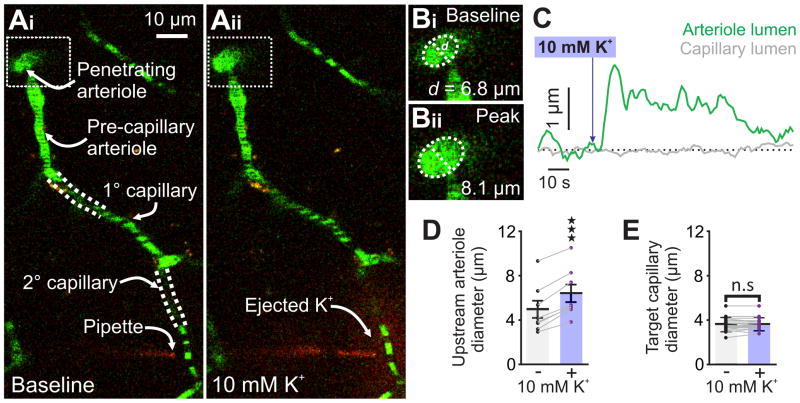

To confirm that hyperemic responses to capillary application of 10 mM K+ result from upstream arteriole dilation, we assessed the diameters of feed arterioles in response to capillary stimulation with K+. Consistent with our blood flow results, delivery of K+ onto a capillary invariably increased upstream feed arteriole diameter (32.9% ± 4.4%; n = 8; Fig. 4a–d; Supplementary Movie 3), but had no effect on the diameter of the stimulated capillary (Fig. 4e).

Fig 4.

10 mM K+ applied to capillaries causes upstream arteriolar dilation in vivo. (Ai) Micrograph illustrating pipette placement adjacent to a second-order capillary for in vivo monitoring of the diameter of the upstream feed arteriole (boxed). White dashed lines indicate that capillaries are connected into a single tree despite deviating from the imaging plane. (Aii) The same experiment, after pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ and TRITC (red) around the capillary. Note the dilation in the feed arteriole (boxed). (B) Magnification of the boxed areas around the feed arteriole in Ai and Aii, illustrating the magnitude of dilation evoked by capillary stimulation with 10 mM K+. (C) Traces illustrating the luminal diameter of a pre-capillary arteriole (green) and the stimulated capillary (grey) before and after stimulation with 10 mM K+. Delivery of K+ produced a robust dilation in the arteriole, but not the capillary. (D) Summary data showing arteriole diameter before and after capillary application of 10 mM K+, which produced significant upstream arteriole dilation (n = 8 paired experiments, 7 mice; ****P < 0.0001 (t7 = 10.86) paired Student’s t-test). (E) Summary data showing target capillary diameter before and after capillary application of 10 mM K+, which had no effect (n = 18 capillaries, 7 mice P = 0.6014 (t17 = 0.5324) paired Student’s t-test). All error bars represent s.e.m.

Endothelial KIR2.1 channels are the primary actuators of K+ evoked increases in CBF and are critical for functional hyperemia

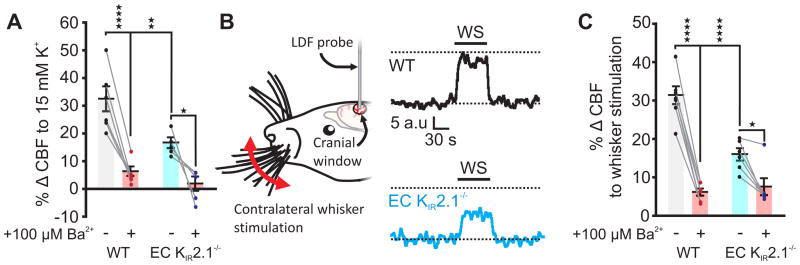

To examine the role of EC KIR2.1 channels in K+-evoked cerebral hyperemia in vivo, we recorded CBF in a volume of the somatosensory cortex through a cranial window using laser Doppler flowmetry. Application of 15 mM K+ to the cranial surface caused a robust increase in cortical CBF that was strongly inhibited (by 80%) by 100 μM Ba2+ in WT mice and greatly diminished (by 49%) in EC KIR2.1−/− mice, supporting the conclusion that EC KIR2.1 channels have a major role in K+-induced hyperemia (Fig. 5a). To confirm that this KIR2.1 channel-dependent mechanism is engaged during functional hyperemia—as implied by previous reports that Ba2+ substantially reduces neural activity-evoked increases in CBF27,29–31—we measured CBF responses evoked by whisker stimulation. Whisker stimulation-evoked CBF increases were markedly blunted (by 49%) in EC KIR2.1−/− mice (Fig. 5b,c) and following application of 100 μM Ba2+ (by 80%) in WT mice (Fig. 5c), consistent with cEC KIR2.1 channels playing an essential role in functional hyperemia. The residual Ba2+-sensitive component of K+- (Fig. 5a) and whisker stimulation-induced (Fig. 5c) functional hyperemia in EC KIR2.1−/− mice is likely attributable to the direct engagement of SM KIR2.1 channels by topically applied K+ and K+ released from astrocytic endfeet during NVC, respectively, as previously demonstrated12,27. However, Ba2+ could also have direct effects on neural activity. To explore this possibility, we assessed local field potentials (LFPs) in the barrel cortex, evoked by whisker stimulation before and after 100 μM Ba2+ superfusion. Whisker stimulation elicited clear LFP oscillations of 5.0 ± 0.1 Hz both with and without Ba2+ (Supplementary Fig. 12), consistent with the conclusion that, under these conditions, neural activity in response to whisker stimulation is maintained in the presence of Ba2+. Notably, a 5-fold higher concentration of Ba2+ than that used here also has no effect on sensory-evoked neural activity32, reinforcing our conclusion that the vasculature is the major target of Ba2+ in our in vivo experiments. As expected, hyperemic responses were preserved in KIR2.1fl/fl and Tek-Cre controls (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 5.

EC KIR2.1 channels are essential for functional hyperemia. (A) Summary data for 15 mM K+-evoked hyperemia. Responses in WT mice were severely attenuated by 100 μM Ba2+. Responses in EC KIR2.1−/− mice were significantly smaller than those from WT mice and almost abrogated by 100 μM Ba2+ (WT, n = 6 mice; EC KIR2.1−/−, n = 5 mice. ****P < 0.0001 (q18 = 9.033), **P = 0.0083 (q18 = 5.214), *P = 0.0187 (q18 = 4.676); two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (B) Left: Whisker stimulation experimental paradigm. Right: Typical traces illustrating the hyperemic response to whisker stimulation (WS), measured using laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF). Hyperemia in EC KIR2.1−/− mice (blue) was markedly blunted compared with that in WT mice (black). Black dashed lines represent baseline and peak WT response for comparison. (C) Summary data for functional hyperemia, indicating that responses in WT mice are driven by a substantial Ba2+-sensitive component, which is greatly diminished in EC KIR2.1−/− mice (WT, n = 7 mice; EC KIR2.1−/−, n = 6 mice; ****P < 0.0001 (q22 = 14.3 WT vs. Ba2+, and 8.396 WT vs. EC KIR2.1−/−), *P = 0.0238 (q22 = 4.413); two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). All error bars represent s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

A single microliter of the cortex contains almost one meter of total vascular length33, with capillaries vastly outdistancing arterioles and venules in their reach. The number of cECs in the brain closely matches that of neurons34, and each brain capillary is < 15 μm from the nearest neuronal cell body35. This anatomical arrangement invites the hypothesis that long-range conducted signaling from capillaries to upstream arterioles would be an efficient way to direct blood flow to the deep microcirculation in response to neuronal activity. Our findings provide strong experimental evidence in support of this concept, indicating that brain capillary networks function as a sensory web to relay information about neuronal activity to upstream arterioles and pial arteries. Specifically, our data support a mechanism in which activation of cEC KIR2.1 channels by K+ released during neural activity initiates a rapidly propagating hyperpolarization, conceptualized as an “inverse action potential”, that drives upstream arteriolar dilation, promoting rapid hyperemia at the site of the K+ increase (Supplementary Fig. 13). Because K+ ions are released during each neuronal action potential, this mechanism provides a means for tightly coupling CBF to the rhythms of neuronal firing within the brain, and places capillaries at center stage in the moment-to-moment control of CBF.

Brain cECs are phenotypically distinct from their arteriolar counterparts

To date, there has been a paucity of information regarding which ion channels are expressed in brain cECs and how they affect capillary function. Our characterization of the ion channel repertoire of ECs in brain capillaries addresses this deficit, and provides important insights into both similarities and differences between these ECs and those in other vascular beds.

Critical for our functional model, we detected Kcnj2 transcripts in freshly isolated mouse brain capillary ECs and recorded strongly rectifying KIR currents from these cells that were sensitive to 100 μM Ba2+, a concentration relatively selective for KIR2 channels. Importantly, these currents were absent in EC KIR2.1−/− mice. These observations firmly establish that brain cECs possess functional KIR2 channels and demonstrate that the KIR2.1 subunit is an essential component of this channel complex.

To our surprise, we found no evidence for Ca2+-activated SK or IK channels in cECs. This observation stands in stark contrast with all previously tested arteriolar ECs, which possess prominent SK and IK currents19. This finding is significant, in part, because it illustrates that cECs are not merely a continuation of the arteriolar endothelium, but instead are phenotypically distinct from their arteriolar counterparts. Functionally, the absence of these channels could support optimal electrical signaling along the capillary by removing an avenue for current leak.

Extracellular K+ drives capillary-to-arteriole electrical communication, causing upstream dilation

Action potentials, the defining feature of neuronal activity, are composed of an upstroke mediated by influx of Na+ via voltage-dependent Na+ channels and a repolarization phase attributable to K+ efflux mediated by a variety of K+ channels. Our model implicitly assumes that the activity of these latter channels underlies the increase in extracellular K+ that triggers EC KIR2.1-dependent electrical signaling, but other sources of K+ could also contribute. Prominent among these are astrocytes, which mediate arteriolar dilation in response to neuronal activation by releasing K+ onto parenchymal arterioles through large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels in astrocytic endfeet, thereby activating SM KIR channels12,27. Astrocytes also enwrap capillaries and almost completely encase the intracerebral vasculature36, unlike neuronal processes, which terminate on the vasculature more rarely37. Thus, this mechanism offers another likely avenue for K+ release onto capillaries, although this awaits experimental confirmation.

Our novel CaPA preparation provided the means to experimentally test the ability of capillaries to rapidly transmit a propagating vasodilatory signal in response to local increases in extracellular K+. Using this approach, we demonstrated that restricted application of a dilating concentration of K+ (10 mM) onto a capillary extremity caused rapid dilation of an attached, upstream arteriolar segment with myogenic tone. Direct evidence that this represents EC-to-SM electrical conduction is provided by experiments showing that stimulation of capillary extremities with 10 mM K+ resulted in arteriolar SM hyperpolarization. This hyperpolarization was detectable within 240 ms of the onset of stimulation ~500 μm distant from the stimulus site. This translates to a hyperpolarization conduction velocity of ~2 mm/s, a rate that is consistent with electrical transmission.

Conducted hyperpolarization implies electrical coupling between brain cECs, as has been demonstrated in peripheral vascular beds6,38. Electrical conduction in arterioles is enabled by the presence of gap junctions, formed from homo- or heteromeric assemblies of connexin (Cx) proteins, between ECs, between SM cells, and between ECs and SM at myoendothelial projections39. Notably, mRNAs for Cx37, Cx43 and Cx45 have been detected in acutely isolated brain ECs40, providing a potential molecular basis for the observed cell-cell electrical coupling in brain capillaries. The fact that capillary-applied K+ failed to evoke upstream dilation when the capillary-arteriole connection was severed also supports the conclusion that an intact capillary-arteriole continuum is essential for transmission, and rules out a mechanism involving the release and diffusion of other vasoactive mediators. Our experimental findings thus imply that cECs form an electrically connected syncytium—analogous to a series of wires throughout the brain—that is coupled to the overlying SM at the arteriolar level.

K+/KIR2.1-mediated capillary-to-arteriole communication underlies functional hyperemia in vivo

The hyperemic effect of small elevations of extracellular K+ in the cerebral circulation has been appreciated for more than 40 years41, but the precise cellular and molecular target of K+ in the cerebral circulation has so far eluded firm identification. Our demonstration that the increase in CBF induced by surface application of 15 mM K+ in a cranial window model was strongly inhibited by 100 μM Ba2+ and dramatically reduced in EC KIR2.1−/− mice firmly establishes a KIR2.1-containing channel as the molecular mediator of K+-induced hyperemia.

Our K+/KIR-dependent, capillary-mediated mechanism predicts that, in vivo, increases in vessel diameter will occur first in the most distal segment of the pial artery/parenchymal arteriole tree (i.e., most capillary-proximate) and spread progressively upstream to pial arteries. Indeed, in vivo imaging studies have revealed that dilation in response to neural activity proceeds in this manner2. These neurally driven dilations conduct at an apparent rate of 1–2 mm/s—a speed that is consistent with our measurements and argues for an underlying electrical mechanism.

It is this dilation of upstream arteries/arterioles that ultimately promotes a hyperemic response in the capillary bed where the triggering K+ signal originates. Experiments in which we extended our K+/KIR-mediated, capillary-based communication mechanism in vivo are consistent with this, showing that local pressure ejection of 10 mM K+ onto a capillary segment within the cortical parenchyma via a pipet caused dilation of the connected upstream arteriole and a subsequent increase in RBC flux and velocity in the stimulated capillary. Importantly, these responses were abrogated in the presence of 100 μM Ba2+ and were absent in EC KIR2.1−/− mice, confirming that cEC KIR2.1 channels are necessary for the hyperemic effect of local elevations in K+. A potential confounding issue in vivo is indirect effects of K+ on other cell types. For example, raising K+ could depolarize neurons and cause the release of other vasoactive factors. To control for this possibility, we performed experiments in the presence of tetrodotoxin, to block neuronal action potentials. As expected, whisker stimulation-evoked increases in capillary flux were completely eliminated by this maneuver, but hyperemic responses to subsequent pressure ejection of K+ onto capillaries persisted. These data further strengthen our conclusion that the observed in vivo responses are attributable to signaling inherent to the capillary wall, and are not the byproduct of inadvertent neuronal activation.

In a final test of the physiological significance of endothelial KIR2.1 channels in functional hyperemia, we measured changes in CBF induced by whisker stimulation in WT and EC KIR2.1−/− mice. Laser Doppler flowmetry revealed that the robust increases in CBF observed in WT mice were decreased by 50% in EC KIR2.1−/− mice. Importantly, Ba2+ eliminated all but ~20% of the hyperemic response in WT mice and reduced the evoked response in EC KIR2.1−/− mice to a similar level. Possible explanations for the residual Ba2+-sensitive component in our EC KIR2.1−/− mouse include direct activation of SM KIR2.1 channels by K+ released from adjacent astrocytic endfeet12,27 and recruitment of SM KIR2.1 channels by hyperpolarization resulting from other signaling mediators, such as PGE2, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, or nitric oxide3. Either of these explanations would imply that KIR channels on SM are necessary for full manifestation of the hyperemic response to any NVC mediator, since hyperpolarization is a necessary step in vasodilation.

The capillary sensory web in context

Whether blood flow control in response to tissue metabolic requirements originates in capillaries is a long-standing question. Indeed, we proposed over 20 years ago that capillaries couple metabolic demand to increases in blood flow in cardiac muscle42. More recently, Atwell and colleagues suggested that functional hyperemia is initiated at the capillary level by pericyte relaxation mediated by neuronally derived PGE2, and reported that capillaries themselves dilate before upstream arterioles following stimulation43. It is important to note that, although we have not detected capillary dilation in response to stimulation, the continuous segments in which we measured capillary diameters lacked pericytes (based on images obtained using co-delivered TRITC). Thus, it is possible that overlying pericytes, if present at locations where stimuli were delivered, could regulate local capillary diameter, a possibility consistent with certain features of the model proposed by Attwell and colleagues44. Evidence from retinal preparations indicates that pericytes are electrically coupled to cECs44 and express KIR channels45. Thus, it is also conceivable that pericytes could provide input into K+/KIR-dependent signaling by amplifying incoming electrical signals during their relay to the upstream arteriole.

Recently, Nedergaard and colleagues46 proposed that a key early component of the hyperemic response to neuronal activity is an increase in capillary erythrocyte velocity resulting from deformation of RBCs in response to neuronal metabolism-induced dips in local O2 tension, reporting that increases in RBC velocity are observed in capillaries before they can be detected in upstream arterioles. This RBC-deformation model lacks a mechanism for increasing upstream arteriolar diameter. This is a major strength of our K+/KIR-dependent electrical conduction mechanism: it provides a means for explaining the rapid upstream dilation that is a consistently reported feature of functional hyperemia2,46,47.

Conclusion

Collectively, our findings recast capillaries as a sensory web dedicated to the rapid and fine control of microcirculatory hemodynamics in support of fluctuating neuronal metabolic demands. In a broader context, similar mechanisms for translating local environmental changes into capillary signals to upstream arterioles likely exist in other electrically active tissues, such as cardiac and skeletal muscle.

ONLINE METHODS

Animal Husbandry

Adult (2–3 months old) male C57/BL6J (referred to as ‘wild-type’; Jackson Laboratories, USA), Acta2-GCaMP5-mCherry (C57/BL6J background, courtesy of M. Kotlikoff, Cornell University), KIR2.1fl/fl, Tek-Cre, and EC KIR2.1−/− mice, all on a C57/BL6J background, were group-housed on a 12-hour light:dark cycle with environmental enrichment and free access to food and water. All animal procedures received prior approval from the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of EC KIR2.1−/− mice

Mice carrying a germline knockout of the KIR2.1 gene specifically in ECs were generated by crossing mice carrying a floxed allele of the KIR2.1 gene Kcnj2 (KIR2.1fl/fl; InGenious Targeting Laboratory, USA) with mice in which Cre recombinase expression is driven by the Tek promoter (Tek-Cre; Jackson Laboratories, USA)17. The presence of LoxP sites and Cre recombinase was confirmed by genotyping offspring prior to all experiments by RT-PCR of tail clip samples using the following primer pairs: LoxP excision site, 5′-GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTG AAA CAG CAT TGC TGT CAC TT-3′ (reverse); Cre recombinase, 5′-GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTG AAA CAG CAT TGC TGT CAC TT-3′ (reverse).

Chemicals

6,7-Dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime (NS309), tetrodotoxin citrate, and 9,11-dideoxy-9α,11α-methanoepoxy PGF2α (U46619) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (USA). Unless otherwise noted, all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (USA).

Electrophysiology

Single ECs and capillary fragments were obtained from mouse brains by mechanically disrupting two 160-μm–thick brain slices in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 4 mM glucose) using a Dounce homogenizer. Debris was removed by passing the homogenate through a 62-μm nylon mesh. Retained capillary fragments were washed into a solution consisting of 55 mM NaCl, 80 mM Na-glutamate, 5.6 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), containing 0.5 mg/mL neutral protease and 0.5 mg/mL elastase (Worthington, USA) plus 100 μM CaCl2, and then incubated for 25 min at 36°C. Following this, 0.5 mg/mL collagenase type I (Worthington, USA) was added for an additional 2 min. Single cells and small capillary fragments were dispersed by triturating 4–6 times with a fire-polished glass Pasteur pipette. Pial ECs and SM cells were obtained by dissecting surface arteries arising from the circle of Willis and the MCA and cleaning them of pia mater. Vessels were then digested using the same conditions as described above for 57 min, with collagenase being added for a final 3 min. Single SM cells, ECs and EC patches were then dispersed by triturating 8–10 times.

Cells were patch-clamped in the conventional whole-cell configuration, and currents were amplified using an Axopatch 200B amplifier. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass (1.5 mm outer diameter, 1.17 mm inner diameter; Sutter Instruments, USA), fire-polished to give a tip resistance of 3–6 MΩ, and filled with a solution consisting of 10 mM NaOH, 11.4 mM KOH, 128.6 mM KCl, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 3.2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES (300 nM free Ca2+; pH 7.2). In a subset of experiments, pipettes were filled with 10 mM NaOH, 6.8 mM KOH, 133.2 mM KCl, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EDTA, and 10 mM HEPES (3 μM free Ca2+; pH 7.2). For 0 [Ca2+]i experiments, the pipette solution consisted of 10 mM NaCl, 11.4 mM KOH, 128.6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). The bath solution consisted of 80 or 134 mM NaCl, 60 or 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM glucose, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). The mean capacitance of capillary ECs was 9.4 ± 0.3 pF (n = 65), corresponding to a membrane surface area of ~940 μm2.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Samples were prepared using a modified isolation protocol, as described previously48. Briefly, capillary branches were isolated and prepared using the Ambion Single Cell-to-CT kit for RT-qPCR (ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). Reactions were then prepared using TaqMan gene expression MasterMix (ThermoFisher Scientific) and primers for KIR2.1 (Kcnj2; RefSeq NM_008425.4) and eNOS (Nos3; RefSeq NM_008713.4) (ThermoFisher Scientific). Transcripts were preamplified for 14 cycles prior to RT-qPCR, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by 40 cycles of qPCR for transcripts of interest. No-template controls were included in all conditions. To account for the possible presence of non-ECs in capillary samples, we normalized Kcnj2 expression in capillaries to expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Nos3).

Isolated pressurized parenchymal arterioles and CaPA preparation

The CaPA extension of our routinely used pressurized arteriolar preparation21–23 in mice was obtained by dissecting parenchymal arterioles arising from the M1 region of the middle cerebral artery, leaving the attached capillary bed intact. Precapillary arteriolar segments were cannulated on glass micropipettes on a Living Systems Instrumentation (USA) pressure myograph, with one end occluded by a tie. The ends of the capillaries were then sealed by the downward pressure of an overlying glass micropipette. Application of pressure (40 mm Hg) to the cannulated parenchymal arteriole segment in this preparation pressurized the entire tree and induced myogenic tone in the parenchymal arteriole segment, as previously described for parenchymal arterioles without capillaries21–23. With this preparation, vasoactive substances were applied at specific points along the capillary-arteriole continuum by pressure ejection from a glass micropipette (tip diameter, 5 ± 1 μm; n = 16) attached to a Picospritzer III (Parker, USA) at 5 ± 2 psi (n = 16) for 18 s (unless otherwise noted). Luminal diameter in parenchymal arterioles was acquired simultaneously in two different regions of the arteriolar segment at 15 Hz using IonWizard 6.2 edge-detection software (IonOptix, USA). Changes in arteriolar diameter were calculated from the average luminal diameter measured over the last 10 s of stimulation.

Membrane potential

For SM membrane potential recordings, parenchymal arterioles, with attached capillary ramifications, were pressurized to 40 mm Hg, as described above. After development of myogenic tone, myosin light chain kinase was inhibited with 800 nM wortmannin to prevent movement artifacts. Myocytes were then impaled with glass microelectrodes filled with 0.5 M KCl (tip resistance, 200–250 MΩ). A WPI Intra 767 amplifier was used for recording membrane potential. Analog output from the amplifier was obtained using AxoScope (Molecular Devices) software (sampling frequency, 417 Hz). Criteria for accepting recordings were (i) an abrupt negative deflection of potential as the microelectrode was advanced into the cell, (ii) stable membrane potential for at least 1 min, and (iii) an abrupt change in potential to ~0 mV after retracting the electrode from the cell.

Fluorescence staining

CaPA preparations were prepared from brain tissue isolated from Acta2-GCaMP5-mCherry mice and incubated with FITC-conjugated isolectin B4 (10 μg/mL) in aCSF for 30 min. Fluorescence was visualized with an Andor Revolution confocal system (Andor Technology, UK) equipped with an upright 10x objective (NA 0.25) and CCD camera.

In vivo imaging of cerebral hemodynamics

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2% maintenance). Upon obtaining surgical-plane anesthesia, the skull was exposed and a stainless steel head plate was attached over the left hemisphere using a mixture of dental cement and superglue. The head plate was secured in a holding frame, and a small (~2-mm diameter) circular cranial window was drilled in the skull above the somatosensory cortex. Approximately 300 μL of a 1-mg/mL solution of FITC (molecular weight, 2000 kDa) in saline was injected via the tail vein to allow visualization of the cerebral vasculature and contrast imaging of RBCs. Upon conclusion of surgery, isoflurane anesthesia was replaced with α-chloralose (50 mg/kg) and urethane (750 mg/kg). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment using an electric heating pad. Penetrating arterioles were first identified by observing RBCs flowing into the brain (as opposed to out of the brain via venules), and capillaries downstream of arterioles were selected for study. A pipette was next introduced into the solution covering the exposed cortex, and the duration and pressure of ejection were calibrated (200–300 ms, 8 ± 1 psi; n = 59) to obtain a small solution plume (radius, ~10 μm). The pipette was maneuvered into the cortex and positioned adjacent to the capillary under study (mean depth, 73 ± 6 μm; n = 19), after which agents were ejected directly onto the capillary. Placement of the pipette in the brain as described restricted agent delivery to the capillary under study and caused minimal displacement of the surrounding tissue (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Movies 2 and 3). Spatial coverage of the ejected solution was monitored by including tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC, 150 kDa; 0.2 mg/mL)-labeled dextran. RBC velocity and flux data were collected by line scanning the capillary of interest at 5 kHz. For experiments in which KIR channels or neural activity were blocked, 100 μM BaCl2 or 3 μM tetrodotoxin in aCSF, respectively, was applied to the cranial surface for a minimum of 20 min to allow penetration. Whisker stimulation was performed using a piezoelectric actuator driven by a waveform generator coupled to an amplifier (Piezo Master; Viking Industrial Products). Whiskers were stimulated at a frequency of 4 Hz for 1 min with a total deflection of 5 mm. Images were acquired through a Zeiss 20x Plan Apochromat 1.0 NA DIC VIS-IR water-immersion objective mounted on a Zeiss LSM-7 multiphoton microscope (Zeiss, USA) coupled to a Coherent Chameleon Vision II Titanium-Sapphire pulsed infrared laser (Coherent, USA). FITC and TRITC were excited at 820 nm, and emitted fluorescence was separated through 500–550 and 570–610 nm bandpass filters, respectively.

Laser Doppler flowmetry

Functional hyperemia in the whisker barrel cortex was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry, as previously described27. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2% maintenance). At the conclusion of surgery, isoflurane anesthesia was withdrawn and replaced with α-chloralose (50 mg/kg) and urethane (750 mg/kg). Body temperature was monitored with a rectal probe and maintained at 37°C by a servo-controlled heating pad. The femoral artery was catheterized for mean arterial pressure recording and blood gas measurement (Supplementary Table 2). The head was immobilized using a stereotactic frame and the cisterna magna was punctured to relieve intracranial pressure, after which a 2 × 2 mm cranial window was prepared over the whisker barrel cortex. The window was continuously superfused with aCSF, and a laser Doppler flow probe (Perimed) was placed over the window for CBF measurement. Arterial pressure and CBF were recorded using PowerLab software (AD Instruments), and were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min before experimentation. Functional hyperemia was assessed by stimulating contralateral whiskers. Whiskers were stimulated at a frequency of ~4 Hz for 1 min. Ba2+ (100 μM) was delivered via the cranial window superfusate.

In vivo electrophysiology

Local field potentials (LFPs) in the whisker barrel cortex were recorded essentially as previously described49. Briefly, a cranial window was prepared as described above, after which a 2 × 4 array of tetrodes (25 μm Nichrome wire, AM–Systems Inc., USA) was implanted in the whisker barrel cortex. A ground wire was implanted over the cerebellum through a separate (~0.5 × 0.5 mm) window. Neuronal activity was recorded in response to contralateral whisker stimulation. Signals were pre-amplified x 1 at the headstage, and were sampled at 30 kHz and filtered at 1–9000 Hz (Neuralynx, MT, USA). All LFP signals were referenced against the ground wire placed above the cerebellum. Whiskers were stimulated manually at a frequency of ~4–6 Hz for 1 min. Ba2+ (100 μM) was delivered in aCSF via the cranial window superfusate.

Data analysis

Patch-clamp data were analyzed using Clampfit 9.2 software. In diameter and membrane potential experiments, response onset was measured for deflections from baseline > 5%. Changes in arteriolar diameter were calculated from the average luminal diameter measured over the last 10 s of stimulation. RBC flux and velocity were analyzed offline using ImageJ software. RBC velocity was calculated from measurements of the angle of each individual RBC appearing on the linescan. Flux data were binned at 1-s intervals. Mean baseline velocity and flux data for summary figures were obtained by averaging the baseline (~3 s) for each measurement prior to pressure ejection of 10 mM K+. The peak response was defined as the peak 1-s flux bin after delivery of K+ within the remaining scanning period (~17 s). Because flux and velocity are correlated, the average velocity of all cells in the peak flux bin was reported for velocity summary data. The distance from the site of pressure ejection to the feed arteriole was estimated using the Pythagorean theorem applied to manual measurements taken along the x-, y-, and z-axes of z-stack image series taken of the local vasculature at the time of pipette placement. The depth of capillaries below the surface was estimated from z-stack series acquired prior to pipette placement. The CBF response to whisker stimulation was quantified by calculating the total area under the curve of the CBF trace during the 60-s whisker stimulation period. LFPs were analyzed with custom written software using the Matlab Signal Processing and Chronux50 toolboxes and were initially notch filtered to remove 60 Hz noise. Spectrograms were computed from fast Fourier transforms. Whisker stimulation reliably evoked clear oscillations between approximately 4 and 6 Hz and therefore we focused our analysis primarily on this band of interest, assessing mean frequency and signal magnitude in 8 s epochs starting 10 s after the stimulus onset. We also analyzed the mean frequency and peak magnitude of oscillations in 0–4 and 6–20 Hz bands.

Statistics

Statistical testing was performed using Graphpad Prism 6 software. Data are expressed as means ± SEM, and a P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Stars denote significant differences, ‘n.s.’ indicates non-significant comparisons. Statistical tests are noted in figure legends. All t-tests were two-sided. All data passed the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, and experiments were repeated to adequately reduce confidence intervals and avoid errors in statistical testing. Sample size estimation was predicated on similar experiments performed previously in our laboratory. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Randomization was not performed and exclusions were not made.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge J. Barry for assistance with LFP recordings and analysis, and S. O’Dwyer and M. Ross for technical assistance. This study was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (14POST20480144 to TAL) and a scientist development grant (14SDG20150027 to MK) from the American Heart Association, and grants from the United Leukodystrophy Foundation (FD), the Totman Medical Research Trust (MTN), Fondation Leducq (MTN), EC Horizon 2020 (MTN), and National Institutes of Health (R01-HL-136636 to FD; T32HL-007594 to ALG; K01-DK103840 to NRT; P30-GM-103498 to the COBRE imaging facility at UVM College of Medicine; P01-HL-095488, R01-HL-121706, R37-DK-053832 and R01-HL-131181 to MTN).

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS

T.A.L acquired and analyzed patch clamp electrophysiology data, provided tissue for RT-qPCR, acquired and analyzed in vivo hemodynamics and diameter data, acquired and analyzed LFP data, wrote the initial draft, and edited the manuscript. F.D developed the CaPA preparation, acquired and analyzed all CaPA preparation data and edited the manuscript. M.K. acquired and analyzed laser Doppler flowmetry data. A.L.G acquired fluorescent-staining data and edited the manuscript. N.R.T acquired and analyzed RT-qPCR data. J.E.B edited the manuscript. D.H.E contributed significantly to the study design and edited the manuscript. M.T.N conceived and directed the study, and wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved its submission.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

None.

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Iadecola C, Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nn2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uhlirova H, et al. Cell type specificity of neurovascular coupling in cerebral cortex. Elife. 2016;5:e14315. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attwell D, et al. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:365–370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609551104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blinder P, et al. The cortical angiome: an interconnected vascular network with noncolumnar patterns of blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:889–897. doi: 10.1038/nn.3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach JM, McGahren ED, Duling BR. Capillaries and arterioles are electrically coupled in hamster cheek pouch. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1489–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aydin F, Rosenblum WI, Povlishock JT. Myoendothelial junctions in human brain arterioles. Stroke. 1991;22:1592–1597. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.12.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballanyi K, Doutheil J, Brockhaus J. Membrane potentials and microenvironment of rat dorsal vagal cells in vitro during energy depletion. J Physiol. 1996;495:769–784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longden TA, Nelson MT. Vascular inward rectifier K+ channels as external K+ sensors in the control of cerebral blood flow. Microcirculation. 2015;22:183–196. doi: 10.1111/micc.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quayle JM, Nelson MT, Standen NB. ATP-sensitive and inwardly rectifying potassium channels in smooth muscle. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:1165–1232. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filosa JA, et al. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1397–1403. doi: 10.1038/nn1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledoux J, et al. Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9627–9632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801963105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quayle JM, McCarron JG, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Inward rectifier K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from rat resistance-sized cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 1993;265:C1363–C1370. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.5.C1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibino H, et al. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: Their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:291–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaritsky JJ, Eckman DM, Wellman GC, Nelson MT, Schwarz TL. Targeted disruption of Kir2. 1 and Kir2 2 genes reveals the essential role of the inwardly rectifying K+ current in K+-mediated vasodilation. Circ Res. 2000;87:160–166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye W, et al. K+ channel KIR2.1 functions in tandem with proton influx to mediate sour taste transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;113:E229–238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514282112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonkusare SK, Dalsgaard T, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Inward rectifier potassium (Kir2.1) channels as end-stage boosters of endothelium-dependent vasodilators. J Physiol. 2016;594:3271–3285. doi: 10.1113/JP271652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology. 2006;21:69–78. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strøbæk D, et al. Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1665:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabertrand F, et al. Potassium channelopathy-like defect underlies early-stage cerebrovascular dysfunction in a genetic model of small vessel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E796–805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420765112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dabertrand F, et al. Prostaglandin E2, a postulated astrocyte-derived neurovascular coupling agent, constricts rather than dilates parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:479–82. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabertrand F, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Acidosis dilates brain parenchymal arterioles by conversion of calcium waves to sparks to activate BK channels. Circ Res. 2012;110:285–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannah RM, Dunn KM, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Endothelial SKCa and IKCa channels regulate brain parenchymal arteriolar diameter and cortical cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;31:1175–1186. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nystoriak MA, et al. Fundamental increase in pressure-dependent constriction of brain parenchymal arterioles from subarachnoid hemorrhage model rats due to membrane depolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H803–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00760.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knot H, Zimmermann P, Nelson M. Extracellular K+-induced hyperpolarizations and dilatations of rat coronary and cerebral arteries involve inward rectifier K+ channels. J Physiol. 1996;492:419–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girouard H, et al. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3811–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914722107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayata C, Lauritzen M. Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:953–993. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toussay X, Basu K, Lacoste B, Hamel E. Locus coeruleus stimulation recruits a broad cortical neuronal network and increases cortical perfusion. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3390–3401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3346-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vetri F, Xu H, Paisansathan C, Pelligrino DA. Impairment of neurovascular coupling in type 1 diabetes mellitus in rats is linked to PKC modulation of BKCa and Kir channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1274–1284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01067.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masamoto K, et al. Unveiling astrocytic control of cerebral blood flow with optogenetics. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11455. doi: 10.1038/srep11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leithner C, et al. Pharmacological uncoupling of activation induced increases in CBF and CMRO. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:311–322. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shih AY, et al. Robust and fragile aspects of cortical blood flow in relation to the underlying angioarchitecture. Microcirculation. 2015;22:204–218. doi: 10.1111/micc.12195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-Amado M, Prensa L. Stereological analysis of neuron, glial and endothelial cell numbers in the human amygdaloid complex. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai PS, et al. Correlations of neuronal and microvascular densities in murine cortex revealed by direct counting and colocalization of nuclei and vessels. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14553–14570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3287-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, Liu QS, Nedergaard M. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cauli B, et al. Cortical GABA interneurons in neurovascular coupling: Relays for subcortical vasoactive pathways. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8940–8949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3065-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang T, Wu DM, Xu GZ, Puro DG. The electrotonic architecture of the retinal microvasculature: modulation by angiotensin II. J Physiol. 2011;589:2383–2399. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Figueroa XF, Duling BR. Gap junctions in the control of vascular function. Antiox Redox Signal. 2009;11:251–266. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuschinsky W, Wahl M, Bosse O, Thurau K. Perivascular potassium and pH as determinants of local pial arterial diameter in cats. A microapplication study. Circ Res. 1972;31:240–247. doi: 10.1161/01.res.31.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daut J, Standen NB, Nelson MT. The role of the membrane potential of endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the regulation of coronary blood flow. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1994;5:154–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1994.tb01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall CN, et al. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature. 2014;508:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu DM, Minami M, Kawamura H, Puro DG. Electrotonic transmission within pericyte-containing retinal microvessels. Microcirculation. 2006;13:353–363. doi: 10.1080/10739680600745778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsushita K, Puro DG. Topographical heterogeneity of KIR currents in pericyte-containing microvessels of the rat retina: effect of diabetes. J Physiol. 2006;573:483–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei HS, et al. Erythrocytes are oxygen-sensing regulators of the cerebral microcirculation. Neuron. 2016;91:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen BR, Kozberg MG, Bouchard MB, Shaik MA, Hillman EMC. A critical role for the vascular endothelium in functional neurovascular coupling in the brain. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000787–e000787. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westcott EB, Goodwin EL, Segal SS, Jackson WF. Function and expression of ryanodine receptors and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in smooth muscle cells of murine feed arteries and arterioles. J Physiol. 2012;590:1849–1869. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.222083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barry JM, et al. Temporal coordination of hippocampal neurons reflects cognitive outcome post-febrile status epilepticus. EBioMedicine. 2016;7:175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitra P, Bokil H. Observed Brain Dynamics. Oxford University Press; Oxford; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.