Abstract

Background and Purpose

Brain arteriovenous malformation (bAVM) is an important risk factor for intracranial hemorrhage. Current therapies are associated with high morbidities. Excessive vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been implicated in bAVM pathophysiology. Because soluble FLT1 binds to VEGF with high affinity, we tested intravenous (IV) delivery of an adeno-associated viral vector serotype 9 expressing soluble FLT1 (AAV9-sFLT1) to alleviate the bAVM phenotype.

Methods

Two mouse models were used. Model 1: bAVM was induced in R26CreER;Eng2f/2f mice through global Eng gene deletion and brain focal angiogenic stimulation; AAV2-sFLT02 (an AAV expressing a shorter form of sFLT1) was injected into the brain at the time of model induction, and AAV9-sFLT1, IV-injected eight weeks after. Model 2: SM22αCre;Eng2f/2f mice had a 90% occurrence of spontaneous bAVM at 5 weeks of age and 50% mortality at 6 weeks; AAV9-sFLT1 was IV-delivered into 4–5-week-old mice. Tissue samples were collected four weeks after AAV9-sFLT1 delivery.

Results

AAV2-sFLT02 inhibited bAVM formation and AAV9-sFLT1 reduced abnormal vessels in Model 1 (GFP vs sFLT1: 3.66 ± 1.58/200 vessels vs 1.98 ± 1.29, p<0.05). AAV9-sFLT1 reduced the occurrence of bAVM (GFP vs sFLT1: 100% vs 36%) and mortality [GFP vs sFLT1: 57% (12/22 mice) vs 24% (4/19 mice), p<0.05] in Model 2. Kidney and liver function did not change significantly. Minor liver inflammation was found in 56% of AAV9-sFLT1-treated Model 1 mice.

Conclusion

By applying a regulated mechanism to restrict sFLT1 expression to bAVM, AAV9-sFLT1 can potentially be developed into a safer therapy to reduce the bAVM severity.

Keywords: adeno-associated viral vector, brain arteriovenous malformation, intravenous delivery, mouse model, soluble FLT1

Subject Terms: Angiogenesis, Animal Models of Human Disease, Gene Therapy

Introduction

Brain arteriovenous malformations (bAVMs) tend to rupture spontaneously causing intracranial hemorrhage. Current treatments are associated with high morbidities/mortalities. New, effective and safe therapies are therefore needed.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is abnormally high in bAVM lesions.{Hashimoto, 2005 #17519} Patients with an autosomal dominant disease, Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), have a higher incidence of AVMs in multiple organs, including the brain. Increased VEGF has also been found in HHT patients’ plasma.{Sadick, 2005 #20623} Therefore, inhibiting VEGF may be effective to treat bAVM. However, considerable side effects are associated with commonly used blocking agents: VEGF antibodies{Tabouret, 2015 #28879} and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.{Orphanos, 2009 #28984}

Soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFLT1) contains only the extracellular domains of FLT1 (VEGFR1) and binds with VEGF.{Chung, 2011 #27673}

The adeno-associated virus (AAV) mediates long-term transgene expression in non-dividing cells. AAV serotype 9 (AAV9) passes through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) around the angiogenic region.{Shen, 2015 #27708} Intravenous (IV) injection of AAV9-sFLT1 inhibits VEGF-induced brain angiogenesis.{Shen, 2015 #27708}

Our study shows that through intra-brain or IV injection, AAV-sFLT1 attenuates bAVM phenotypes.

Methods

Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of California, San Francisco approved protocol/experimental procedures. IACUC and Animal Care Facility staff provided animal husbandry.

Eng2f/2f (Endoglin, HHT-causative gene) mice{Allinson, 2007 #22490} were crossbred with R26CreER or SM22αCre mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to produce R26CreER;Eng2f/2f or SM22αCre;Eng2f/2f mice.

Model 1

8-week-old R26CreER;Eng2f/2f mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (2.5 mg/25g of body weight) daily for three consecutive days to globally delete the Eng gene, and intra-brain injected with AAV1-VEGF to induce focal angiogenesis when the first dose of tamoxifen was given; bAVM developed 8 weeks later.{Choi, 2014 #27084} AAV1-sFLT02 was co-injected with AAV1-VEGF at the time of model induction, and AAV9-sFLT1, IV-injected 8 weeks after.

Model 2

SM22αCre;Eng2f/2f mice. AAV9-sFLT1 was IV-injected to 4–5-week-old mice.

Random group assignment was applied, and treatment endpoint selected based on a previous study.{Shen, 2015 #27708}

Statistics

Sample sizes are shown in the figures. GraphPad Prism 6 was used to analyze data, T-test for comparing two groups, and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for more than two groups with multiple comparisons. Survival rate was analyzed using Log-rank test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All methods are described in the online-only Supplemental Data.

Results

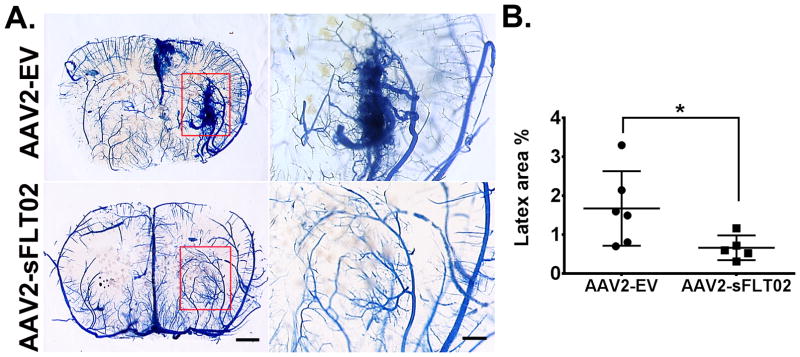

To test whether sFLT1 inhibits bAVM formation, AAV2-sFLT02 containing the VEGF binding domain 2 of human sFLT1 and a CH3 domain of IgG1{Shen, 2015 #27708} was co-injected with AAV1-VEGF into the brain of Model 1 mice when the first dose of tamoxifen was given. Eight weeks later, cerebrovasculature was latex-cast (Supplemental Figure IA & B). Due to size, latex particles enter the veins only when there is an arteriovenous shunt (an AVM hallmark). BAVMs were detected in AAV2-EV-treated mice, but not in AAV2-sFLT02-treated mice (Figure 1A). AAV2-sFLT02-treated mice had a smaller latex-perfused area than AAV2-EV-injected mice (p=0.037; Figure 1B; Supplemental Figure IC), indicating that sFLT02 inhibited bAVM formation.

Figure 1. AAV2-sFLT02 in situ inhibits bAVM in Model 1 (R26CreER;Eng2f/2f).

(A) Representative images: coronal sections - latex-perfused brain. AVM developed in angiogenic regions (rectangles) of AAV2-EV-injected but not in AAV2-sFLT02-injected mice. Right panels: Close-up views: angiogenic region. Scale bars: 1 mm (left) or 500 μm (right). (B) Latex-perfused area quantification. AAV2-EV group: N=6. AAV2-sFLT02 group: N=5. *: p=0.037.

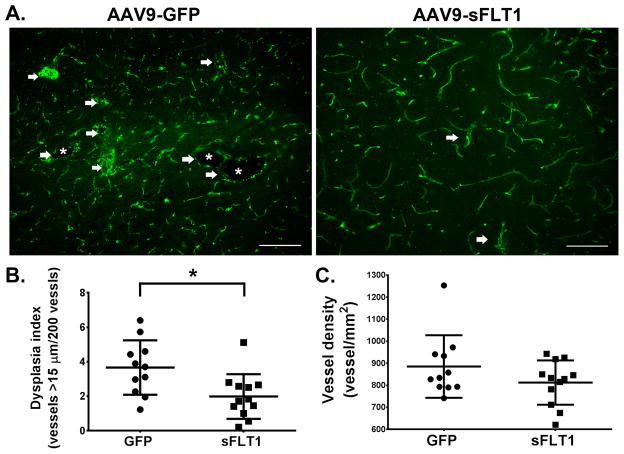

To reduce risk of intra-lesion injection, AAV9-sFLT1 expressing a full-length human sFLT1{Shen, 2015 #27708} or AAV9-GFP (control) was IV-delivered to Model 1 mice eight weeks after model induction when bAVM had developed{Choi, 2014 #27084} (Supplemental Figure IIA & B). Gene expression in bAVM was confirmed via histological analysis for GFP, and ELISA for sFLT1 (Supplemental Figure IIC–E).

Four weeks later, therapeutic effect was evaluated by analyzing vessel density and dysplasia vessels (DI: number of vessels larger than 15μm/200 vessels){Choi, 2014 #27084} using fresh frozen brain sections (Supplemental Figure IIB). Compared with AAV9-GFP-treated mice (3.66 ± 1.58), AAV9-sFLT1-treated mice had a lower DI (1.98 ± 1.29, p =0.011) and a trend toward lower vessel density (p=0.17, Figure 2), indicating that AAV9-sFLT1 reduced bAVM severity. No GFP signal was detected in the fresh frozen sections of Ad-GFP-injected brain (Supplemental Figure III). The positive signals of fluorescent labeled lectin and CD31 antibody staining were completely co-localized (Supplemental Figure IIIB).

Figure 2. AAV9-sFLT1 IV reduces DI in bAVM in Model 1 (R26CreER;Eng2f/2f).

(A) Representative CD31 antibody-stained brain images. White arrows: Abnormal vessels. White stars: Enlarged abnormal vessel lumens. Scale bar=100 μm. (C) DI quantifications. (D) Vessel density quantifications. GFP-treated group: N=11. sFLT1-treated group: N=12. *: p=0.011.

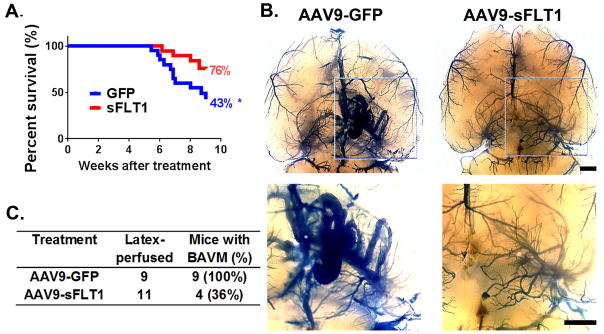

To confirm that the effect in Model 1 was not due to inhibition of exogenous VEGF used to induce bAVM, we tested AAV9-sFLT1 in Model 2, in which bAVMs develop spontaneously without exogenous VEGF stimulation. AAV9-sFLT1 was IV-injected into 4–5 week-old mice (Supplemental Figure IVA), since 90% of Model 2 mice had bAVMs by 5 weeks and 50% died by 6 weeks.{Choi, 2014 #27084} About 57% of AAV9-GFP-treated and 24% of AAV9-sFLT1-treated mice died during the 4-week treatment period (p=0.036; Figure 3A; Supplemental Table I). All AAV9-GFP-treated mice had bAVM; only 36% of AAV9-sFLT1-treated mice had detectable bAVMs (Figure 3B & C; Supplemental Figure IVB–D). Therefore, AAV9-sFLT1 treatment also reduced the severity of spontaneously developed bAVM.

Figure 3. AAV9-sFLT1 IV reduces spontaneously developed bAVM in Model 2 (SM22αCre;Eng2f/2f).

(A) Survival curves. GFP and sFLT1: AAV9-GFP and AAV9-sFLT1 injection. *: p=0.036. (B) Representative latex-cast brains. Top panel: Clarified brain. Bottom panel: Close-up views. Scale bars=1 mm. (C) BAVM rates.

Potential adverse effects on the liver and kidney were analyzed. The activities of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and alanine transaminase (ALT) and the levels of creatinine (Cr) were similar in AAV9-GFP-treated, AAV9-sFLT1-treated, and untreated groups in Model 1 (Supplemental Figure VA–C). Small clusters of inflammatory cells (including monocytes and lymphocytes) were detected in the liver of 58% of AAV9-GFP-treated and 56% of AAV9-sFLT1-treated mice, but not in AAV9-EV-injected mice (Supplemental Figure VD & E; Supplemental Table II). Body weight of AAV9-sFLT1-treated R26CreER;Eng2f/2f mice did not increase as much as control mice during the treatment period, and was lower than the control groups at the end of therapy (p=0.044, Supplemental Figure VI).

Discussion

We tested an anti-angiogenic gene therapy to treat bAVM in: (1) VEGF-induced adult onset model, and (2) spontaneously developed model. We showed that in situ injection of AAV1-sFLT02 at the time of model induction inhibited bAVM formation in Model 1; IV-delivered AAV9-sFLT1 reduced bAVM severity in both models.

VEGF functions mainly through VEGFR1 (or FLT1) and VEGFR2. While VEGFR2 is known to mediate endothelial cell mitosis and vascular permeability, VEGFR1-mediated signaling is complex and context-dependent. VEGF-VEGFR1 signaling also induces monocytes homing to the injured tissue. sFLT1’s effect most likely occurs when it binds to excessive VEGF in the brain parenchyma, thus quenching VEGF signaling through membrane-bound receptors. We found that sFLT1 over-expression reduced dysplasia vessels, with no significant reduction of CD68+ cells in the bAVM (data not shown), suggesting that therapeutic effect might be achieved by reducing VEGFR2 signaling. Although we were not able to quantify the number of dysplasia vessels in Model 2 due to the unpredictable lesion locations, AAV9-sFLT1 reduced mortality and the presence of bAVM in this model, suggesting that the effect observed in Model 1 was not merely through exogenous VEGF inhibition. Future studies will be needed to determine the underlying mechanisms.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment in an adult onset Alk1-deficient model reduced bAVM severity.{Walker, 2012 #25298} However, bevacizumab causes bilateral pulmonary embolisms, thrombosis and hypertension in HHT patients.{Tabouret, 2015 #28879} Although IV-delivered AAV9-sFLT1 caused weight loss and liver inflammation, AAV9-EV did not. Therefore, the side effects were caused by constitutive sFLT1 expression. An anti-tumor study showed ascites and kidney damage in mice treated with adenoviral vector expressing sFLT1 constitutively, but not in mice treated with intermittent sFLT1 expression,{Sivanandam, 2008 #29553} indicating that sFLT1 side effects can be reduced by controlling expression. An AAV gene therapy has been approved recently and many clinical trials are ongoing.{Pollack, 2012 #27085} AAV gene therapy could be developed into a safer and effective therapy to treat chronic diseases such as AVM.

Although our mouse models have many key characteristics of human bAVM,{Walker, 2011 #23922} no hemodynamic changes in the AV fistula and the nearby brain blood vessels have been noted. However, our findings suggest that AAV-sFLT1 could be developed into a minimally invasive and safe anti-angiogenesis gene therapy for bAVM. Minor adverse effects could be minimized by controlling sFLT1 expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS027713, R01 HL122774 and R21 NS083788), the Michael Ryan Zodda Foundation and University of California, San Francisco Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (REAC) to H. Su; and by a Young Investigator Award from Cure HHT (Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia) Foundation to W. Zhu.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Hashimoto T, Wu Y, Lawton MT, Yang GY, Barbaro NM, Young WL. Co-expression of angiogenic factors in brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1058–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadick H, Riedel F, Naim R, Goessler U, Hormann K, Hafner M, et al. Patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia have increased plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 as well as high ALK1 tissue expression. Haematologica. 2005;90:818–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabouret T, Gregory T, Dhooge M, Brezault C, Mir O, Dreanic J, et al. Long term exposure to antiangiogenic therapy, bevacizumab, induces osteonecrosis. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:1144–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orphanos GS, Ioannidis GN, Ardavanis AG. Cardiotoxicity induced by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:964–970. doi: 10.1080/02841860903229124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung AS, Ferrara N. Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:563–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen F, Mao L, Zhu W, Lawton MT, Pechan P, Colosi P, et al. Inhibition of pathological brain angiogenesis through systemic delivery of AAV vector expressing soluble FLT1. Gene Ther. 2015;22:893–900. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allinson KR, Carvalho RL, van den Brink S, Mummery CL, Arthur HM. Generation of a floxed allele of the mouse Endoglin gene. Genesis. 2007;45:391–395. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi EJ, Chen W, Jun K, Arthur HM, Young WL, Su H. Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker EJ, Su H, Shen F, Degos V, Amend G, Jun K, et al. Bevacizumab attenuates VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular malformations in the adult mouse brain. Stroke. 2012;43:1925–1930. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.647982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivanandam VG, Stephen SL, Hernandez-Alcoceba R, Alzuguren P, Zabala M, van Rooijen N, et al. Lethality in an anti-angiogenic tumor gene therapy model upon constitutive but not inducible expression of the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. J Gene Med. 2008;10:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack A. European agency backs approval of a gene therapy. New York Times (New York edition) 2012 Jul;21:B1. Sect B (Health) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker EJ, Su H, Shen F, Choi EJ, Oh SP, Chen G, et al. Arteriovenous malformation in the adult mouse brain resembling the human disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:954–962. doi: 10.1002/ana.22348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.