Abstract

Objective

To describe infant activity at 3 months old and to test the efficacy of a primary care-based child obesity prevention intervention on promoting infant activity in low-income Hispanic families.

Methods

Randomized controlled trial (n=533) comparing a control group of mother-infant dyads receiving standard prenatal and pediatric primary care with an intervention group receiving “Starting Early”, with individual nutrition counseling and nutrition and parenting support groups coordinated with prenatal and pediatric visits. Outcomes included infant activity (tummy time, unrestrained floor time, time in movement restricting devices). Health literacy assessed using the Newest Vital Sign.

Results

456 mothers completed 3-month assessments. Infant activity: 82.6% ever practiced tummy time; 32.0% practiced tummy time on the floor; 34.4% reported unrestrained floor time; 56.4% reported >1 hour/day in movement restricting devices. Inadequate health literacy was associated with reduced tummy time and unrestrained floor time. The intervention group reported more floor tummy time (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.44–3.23) and unrestrained floor time (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.14–2.49) compared to controls. No difference in the time spent in movement restricting devices was found.

Conclusions

Tummy time and unrestrained floor time were low. Primary care-based obesity prevention programs have potential to promote these activities.

Keywords: childhood obesity, physical activity, Hispanics, prevention, intervention

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine's report on early obesity prevention emphasizes the need to increase infant physical activity.1 Although precise definitions of infant activity are challenging, providing opportunities for unrestricted movement may increase activity and energy expenditure. For infants less than 6 months old, caregivers should provide daily “tummy time” (time awake in the prone position) and opportunities for infants to move freely by engaging them unrestrained on the floor (in prone or supine position), and limit the use of equipment that restricts movement, such as bouncy seats or swings. Despite these recommendations, few studies have described patterns of infant tummy time, unrestrained floor time and movement restricting time.2-5

Studies of infant activity have focused on the duration and frequency of tummy time, and none have described how families practice tummy time, such as whether infants are placed on the floor, which allows unrestricted movement, or held on an adult's lap or chest.2,6,7 These studies have found that health literacy, education and ethnicity are related to infant activity. Hispanic mothers and those with inadequate health literacy reported less tummy time,7,8 and university-educated mothers provided more play time than those with less education.3 There has been limited study of movement restricted time.3,9 Given that parents reported infrequently receiving information regarding infant positioning or these devices, and that these messages were confusing and inconsistent,10,11 gaining a better understanding of variations in tummy time, unrestrained floor time and use of movement restricting devices will aid in developing strategies to promote infant activity, especially in high-risk groups.

While the majority of early obesity prevention interventions have incorporated physical activity, few exist for high-risk families.6,12-14 Lower infant physical activity has been associated with increased infant total body fat,15,16 rapid weight gain,17 becoming overweight,17 and greater skin fold thickness.18 To fill this gap, we designed “Starting Early”, a primary care-based early child obesity prevention program targeting low-income Hispanic families beginning in pregnancy and continuing until child age three years old. The primary focus of the intervention is to promote healthy, responsive infant feeding and activity practices. Previous reports have documented positive impacts on infant feeding.19 Findings on infant activity have not been previously reported.

Therefore, we sought to address key gaps in the literature by: 1) describing infant tummy time, unrestrained floor time and movement restricted time; 2) exploring risk factors for lower infant activity, such as maternal health literacy, education and country of origin; 3) testing the efficacy of the “Starting Early” intervention on promoting tummy time and unrestrained floor time and decreasing movement restricted time in low-income Hispanic families; and 4) determining the impact of attending a greater number of intervention sessions.

Methods

Study Design

Study aims were addressed in the context of a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of “Starting Early”, an early child obesity prevention intervention, compared to a standard care control group. This trial was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of New York University School of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center and the New York City Health and Hospital Corporation and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01541761).

Setting

This study took place in a New York City large urban public hospital and an affiliated neighborhood health center.

Sample/Enrollment

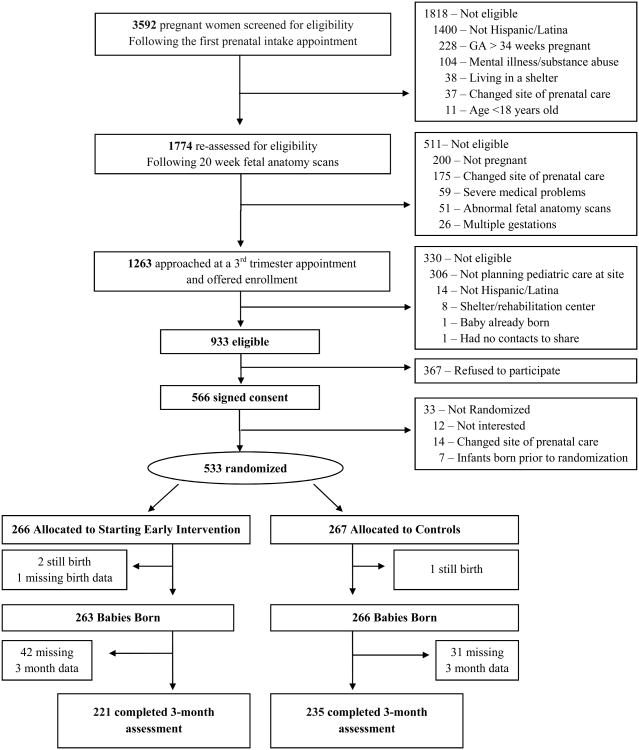

We included pregnant women who were at least 18 years old, Hispanic or Latina, fluent in English or Spanish, with a singleton uncomplicated pregnancy, able to provide contact information and intended to receive care at the study sites.19 We excluded women with severe medical/psychiatric illness or fetal anomalies. Our 3-step process for eligibility screening was previously described (Figure 1).19 Interested eligible women signed informed written consent, and completed baseline assessments. Enrollment took place between August 2012 and December 2014.

Figure 1. Participant enrollment and assessment.

Randomization

Women were randomized to intervention or control groups at a prenatal visit using a random number generator, stratified by site. Research assistants, who conducted the follow-up assessments, were blinded to group assignment.

Starting Early Program

The Starting Early program was a primary care-based child obesity prevention intervention designed for low-income Hispanic families beginning in the third trimester and continuing until child age three years old. The intervention was delivered by bilingual English/Spanish speaking registered dietitians. The main components were: 1) individual nutrition and breastfeeding counseling in the prenatal and postpartum periods, and 2) nutrition and parenting support groups (NPSG) coordinated with all well-child visits in the first three years of life. Groups of 4-8 families participated together from the 1-month visit until 3 years old. Plain language handouts, which were image-based and focused on action-oriented, positive messages, were used to reinforce program messages. A health literacy expert provided feedback on handout development, taking into consideration language, literacy and numeracy demands, and cultural appropriateness.

Nutrition and parenting support groups (NPSG) addressed three domains of skills likely to reduce child obesity: 1) feeding, 2) activity, and 3) parenting skills. The feeding and parenting components were previously described.19 Four program sessions were offered prior to the 3-month old assessment: two individual sessions coordinated with a prenatal visit and the post-partum hospital stay, and two NPSG coordinated with the 1- and 2-month old pediatric visits. During these NPSG sessions, the activity curriculum focused on promoting tummy time and unrestrained floor time, and limiting time in movement restricting devices. These groups promoted role modeling by actively practicing skills, including tummy time on yoga mats and interactively playing by placing themselves or a toy in front of the infant. Messages discussed included: 1) doing daily tummy time; 2) tummy time helps develop motor skills and the habit of playing together; 3) just a few minutes makes a difference; and 4) tummy time can involve the whole family. Messages about the decreased use of movement restricting devices were provided.

Assessments

Telephone-administered surveys in English or Spanish at infant age 3 months were conducted by trained research assistants blinded to intervention status.

Infant Activity

Infant tummy time was assessed by asking: “Does your baby spend time on his/her tummy while awake?” Ever practicing tummy time was defined from the responses “yes” vs. “no”. Infant tummy time in specific locations including the floor, play pen, adult's chest, adult's lap, or bed was determined. The age infants started doing tummy time and the number of days per week and times per day they spent on their tummy while awake were assessed.6

Unrestrained floor time, defined as time spent either in the prone or supine position, was assessed by asking: 1) “How many times per day does your baby spend time on the floor?” and 2) “On average, how many minutes at a time does your baby spend on the floor?” Ever practicing floor time was defined as answering >0 to question 1. We also assessed whether mothers worried about putting infants on the floor.

Movement restricted time was assessed by asking mothers how many times per day and minutes per day the infant spends time in the following devices: 1) a bouncy seat; 2) an indoor baby swing; 3) a car seat when not in a car; and 4) in a stroller when not traveling.3 The number of minutes per day in each device was summed to create a total movement restricted time and dichotomized (less than 60 minutes, > 60 minutes per day) based on median time spent in prior studies.9

Risk Factors for Reduced Infant Activity

We assessed health literacy using the Newest Vital Sign.20 Scores ranged from 0 to 6, with 0–3 indicating inadequate health literacy and 4–6 indicating adequate health literacy. Maternal education (less than high school, high school or more) was assessed. Maternal country of origin was used as a measure of ethnicity (non-US born, US born).

Family Characteristics

Baseline demographic information included maternal age, parity, marital status, work, participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, pre-pregnancy obesity,21 and prenatal depressive symptoms. Prenatal depressive symptoms, defined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (scale of 0–27),22 were dichotomized at recommended cut points with no symptoms (0–4) versus mild or greater symptoms (5–27). Infant characteristics assessed including gender, delivery type (vaginal, C-section), and birth weight.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated that 500 pregnant women would be needed to achieve 80% power to detect a 15% reduction in obesity at age 3 years, assuming 30% attrition, and alpha of .05. SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used. First, we performed univariate analyses to examine baseline distributions of family characteristics by group status. Second, we described the prevalence of tummy time, unrestrained floor time, and time in movement restricting devices in the whole sample. Third, we examined bivariate relationships between the risk factors for reduced activity with tummy time, unrestrained floor time, and movement restricting time in the whole sample using chi square analyses. We performed logistic regression to determine independent associations between these risk factors and infant activity, adjusting for group status and all family characteristics chosen a priori. Each model adjusted for all the same covariates simultaneously. Finally, we examined bivariate relationships between intervention group status and tummy time, unrestrained floor time, and time in movement restricting devices using independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Given that parity and education may not have been equally distributed between intervention and control arms, models to determine intervention effects controlling for these two covariates were performed. These models had similar results to the unadjusted analyses and are not shown. This was an intent-to-treat analysis, with all subjects allocated to their given group and assessed based on this assignment. For continuous variables, effect sizes were obtained using mean differences with associated 95% confidence intervals. For categorical variables, effect sizes were obtained using odds ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals. We added interaction terms to determine if these risk factors (health literacy, education, country of origin) moderated intervention effects. Using within intervention group analyses, we explored the impact of the number of NPSGs attended (0, 1 or 2 sessions) on infant physical activity using chi square analyses.

Results

Study Sample

The study sample was previously described (Figure 1).19 933 women were eligible, 367 declined to participate and 533 were randomized. 456 mother-infant dyads completed the 3-month assessment (86.2% of 529 infants born) and were included in these analyses. These analyses included 221 (84.0%) intervention and 235 (88.3%) control dyads, with a mean (SD) infant age of 3.4 (.6) months.

Groups did not significantly differ for baseline characteristics, although small variations in parity (38.7% vs. 30.8%, p=.08) and education (31.1% vs. 39.4%, p=.08) were found (Table 1). About a third of the women attained less than a high school education and the majority had inadequate health literacy (median score 1.0 (IQR 1.0). The women were primarily non-US born, with most from Mexico (46.0%), Ecuador (15.6%), and the Dominican Republic (5.7%).

Table 1. Baseline Family Characteristics for the 3-Month Analytic Sample.

| Family Characteristics | 3-Month Analytic Sample (n=456) | |

|---|---|---|

| Expectant Mother (Prenatal) | Control (n=235) | Intervention (n=221) |

| Age (mean (SD)), years | 28.1 (5.8) | 29.0 (6.1) |

| Primiparous | 91 (38.7) | 68 (30.8) |

| Married or living as married | 167 (71.1) | 161 (72.9) |

| Working | 36 (15.6) | 40 (18.1) |

| WIC participanta | 202 (86.0) | 199 (90.0) |

| Pre-pregnancy obese statusb | 69 (29.4) | 62 (28.5) |

| US born | 43 (18.3) | 40 (18.1) |

| Prenatal depressive symptomsc | 76 (32.5) | 70 (31.8) |

| Education (less than high school) | 73 (31.1) | 87 (39.4) |

| Adequate health literacyd | 28 (13.7) | 26 (12.9) |

| Child (Birth) | ||

| Male gender | 114 (48.5) | 114 (51.6) |

| C-section | 58 (24.7) | 48 (21.7) |

| Birth weight (mean (SD)), kilograms | 3.40 (.49) | 3.38 (.45) |

WIC - Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Pre-pregnancy obese status was defined as pre-pregnancy BMI > 30.

Depressive symptoms were defined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Mild or greater depressive symptoms were defined with scores of 5–27.

Health literacy measured using the Newest Vital Sign. Adequate health literacy was defined with scores of 4-6.

Rates of Infant Activity

In the whole sample, 82.6% of mothers reported ever practicing tummy time, while 50% reported daily tummy time (Table 2). The majority practiced tummy time on a bed (67.1%) or an adult's chest (57.9%), with 32% on the floor. Only 10.2% reported that their most common location was on the floor. 34.4% reported practicing unrestrained floor time. 44% worried about putting infants on the floor, with the most common worry that infants could get hurt.

Table 2. Infant Activity at 3 Months Old in Study Sample (n=456).

| Infant Activity | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Tummy Time | |

| Tummy time (ever) | 374 (82.6%) |

| Tummy time (daily) | 226 (50.0%) |

| Mean days per week (SD) | 4.55 (2.76) |

| Mean times per day (SD) | 1.91 (1.99) |

| Mean infant age (weeks) for starting tummy time (SD) | 6.76 (5.05) |

| Locations ever used for tummy time | |

| On a bed | 306 (67.1%) |

| On an adult's chest | 264 (57.9%) |

| On an adult's lap | 220 (48.2%) |

| On the floor | 146 (32.0%) |

| In a play pen | 104 (22.8%) |

| Most common location for tummy time | |

| On a bed | 140 (37.4%) |

| On an adult's chest | 84 (22.5%) |

| On the floor | 38 (10.2%) |

| On an adult's lap | 33 (8.8%) |

| In a play pen | 28 (7.5%) |

| Unrestrained Floor Time | |

| Unrestrained floor time (ever) | 155 (34.4%) |

| Mean times per day (SD) | .57 (.99) |

| Worry about putting infant on the floor | 202 (44.6%) |

| Worry about infant getting hurt | 177 (87.6%) |

| Worry about other children | 116 (57.4%) |

| Worry about insects/mice | 80 (39.8%) |

| Worry about infant getting dirty | 77 (38.1%) |

| Worry about pets | 34 (16.8%) |

| Movement Restricted Time | |

| Time in Movement Restricting Devices (ever) | 387 (85.4%) |

| Total restricted time (> 1 hour/day) | 256 (56.5%) |

| Ever use a bouncy seat | 269 (59.4%) |

| Ever use a stroller when not traveling | 123 (27.3%) |

| Ever use an indoor baby swing | 93 (20.5%) |

| Ever use a car seat when not in a car | 59 (13.0%) |

The majority (85.4%) reported using movement restricting devices, with 56.5% reported using them for more than one hour a day. The bouncy seat was most commonly used (59.4%), followed by using a stroller when not traveling (27.3%), indoor infant swing (20.5%) and car seat while inside (13.0%).

Factors Related to Infant Activity

The adjusted relationships between maternal factors and infant activity are shown in Table 3. Mothers with adequate health literacy were more likely to practice floor tummy time (AOR 2.31, 95% CI 1.21–4.42) and unrestrained floor time (AOR 2.23, 95% CI 1.17–4.24). While US born mothers were more likely to practice tummy time (AOR 9.01, 95% CI 1.98–41.04), they were also more likely to have infants spend greater time in movement restricting devices (AOR 2.09, 95% CI 1.11–3.97). Having siblings was not related to floor tummy time (OR 1.28, CI 95% .84–1.95) or unrestrained floor time (OR 1.34, CI 95% .89–2.01).

Table 3. Associations between Maternal Risk Factors and Infant Activity.

| Tummy Time Ever | Tummy Time on the Floor | Unrestrained Floor Time | Time in Movement Restricting Devices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | n (%) | AORa (95% CI) | n (%) | AORa (95% CI) | n (%) | AORa (95% CI) | n (%) | AORa (95% CI) | |

| Adequate health literacy | Yes No |

50 (92.6) 280 (80.0) |

1.64 (.53-5.11) |

26 (48.1) 105 (30.0) |

2.31* (1.21-4.42) |

27 (50.0) 108 (30.9) |

2.23* (1.17-4.24) |

35 (64.8) 193 (55.5) |

1.28 (.66-2.49) |

| High school education | Yes No |

255 (86.7) 119 (74.8) |

1.63 (.90-2.94) |

97 (33.0) 49 (30.8) |

.93 (.57-1.53) |

107 (36.5) 49 (30.8) |

1.07 (.66-1.75) |

172 (58.7) 82 (51.9) |

1.16 (.73-1.85) |

| US born | Yes No |

81 (97.6) 291 (79.1) |

9.01* (1.98-41.04) |

35 (42.2) 110 (29.9) |

1.99* (1.05-3.75) |

37 (44.6) 118 (32.2) |

1.74 (.93-3.25) |

60 (72.3) 193 (52.7) |

2.09* (1.11-3.97) |

Models were adjusted for the three risk factors, intervention group status and family characteristics, including maternal age, parity, marital status, work status, participating in WIC, pre-pregnancy obese status, prenatal depressive symptoms, delivery type, child gender and birth weight simultaneously.

p<.05

Starting Early Impacts on Infant Activity

The intervention group was more likely to practice tummy time (86.4% vs. 78.9%, p=.04, OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.04–2.80) compared to controls (Table 4). The intervention group was more likely to ever practice floor tummy time (40.7% vs. 24.1%, p<.001, OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.44–3.23) and to practice tummy time mostly on the floor (11.8% vs. 5.2%, p=.02, OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.20–4.98). Intervention group mothers practiced more unrestrained floor time (40.6% vs. 28.9%, p=.01, OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.14–2.49). Health literacy, education, and country of origin did not moderate the relationships between intervention group status and tummy time and unrestrained floor time.

Table 4. Effects of the Starting Early Intervention on Infant Activity at Infant Age 3 Months Old.

| Infant Activity | Group (n=456) | p-value | Odds Ratio or Mean Difference | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=235) | Intervention (n=221) | ||||

| Tummy Time | |||||

| Tummy time (ever)a | 183 (78.9%) | 191 (86.4%) | .04* | 1.71 | 1.04 – 2.80 |

| Tummy time (daily)a | 115 (49.6%) | 111 (50.5%) | .93 | 1.04 | .72 – 1.50 |

| Tummy time on the floor (ever)a | 56 (24.1%) | 90 (40.7%) | <.001* | 2.16 | 1.44 – 3.23 |

| Tummy time mostly on the floora | 12 (5.2%) | 26 (11.8%) | .02* | 2.44 | 1.20 – 4.98 |

| Mean times per day (SD)b | 1.87 (1.92) | 1.96 (2.05) | .64 | -.09 | -.46 – .28 |

| Mean infant age (weeks) for starting tummy time (SD)b | 6.90 (4.95) | 6.62 (5.16) | .60 | .28 | -.75 – 1.31 |

| Unrestrained Floor Time | |||||

| Unrestrained floor time (ever)a | 67 (28.9%) | 89 (40.6%) | .01* | 1.69 | 1.14 – 2.49 |

| Mean times per day (SD)b | .43 (.80) | .72 (1.14) | .002* | .29 | .11 – .47 |

| Time in Movement Restricting Devices | |||||

| Restricted time (ever)a | 198 (85.3%) | 187 (85.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | .60 – 1.69 |

| Restricted time (60 minutes or more)a | 136 (58.6%) | 120 (54.3%) | .39 | .84 | .58 – 1.22 |

| Infant bouncy seat (ever)a | 127 (57.5%) | 142 (61.2%) | .45 | .86 | .59 – 1.25 |

| Indoor baby swing (ever)a | 48 (20.7%) | 45 (20.4%) | 1.00 | .98 | .62 – 1.55 |

| Car seat when not in a car (ever)a | 38 (16.4%) | 21 (9.5%) | .04* | .54 | .30 - .95 |

| Stroller when not traveling (ever)a | 57 (24.6%) | 66 (30.1%) | .21 | 1.32 | .87 – 2.01 |

Odds ratio presented for categorical variables.

Mean difference presented for continuous variables.

p<.05

No differences were found between the intervention and control groups for overall time in movement restricted devices (Table 4). Use of individual movement restricting devices was not different except for less use of an infant car seat when not traveling among intervention mothers (9.5% vs. 16.4%, p=.04, OR .54, 95% CI .30–.95).

Intervention Dose

All intervention subjects attended the prenatal session following randomization (221/221). 96.4% received post-partum counseling (213/221) and 56.1% and 58.8% attended the 1-month (124/221) and 2-month (130/221) NPSGs respectively. There were no harms reported. Within the intervention group, increased NPSG attendance was associated with increased tummy time and floor time (Table 5).

Table 5. Intervention Dose Effect on Infant Activitya.

| Number of Interventi on NPSG At tended | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Activity | 0 | 1 | 2 | p-value |

| Tummy time ever (%) | 78.6 | 85.1 | 93.4 | .004 |

| Tummy time on floor (%) | 23.7 | 37.3 | 56.0 | <.001 |

| Unrestrained floor time (%) | 28.5 | 34.8 | 54.4 | <.001 |

Chi square analyses were performed to determine the percentage of mothers performing each physical activity based on the number of Nutrition and Parenting Support Groups (NPSG) they attended. Prior to the 3-month old assessment, mother-infant dyads could have attended 0, 1 or 2 NPSG sessions.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to describe infant tummy time, unrestrained floor time and movement restricting time in low-income Hispanic families. Tummy time and floor time were low, with widespread use of movement restricting devices. Immigrant mothers and those with lower health literacy reported less tummy time, and US born mothers were more likely to use movement restricting devices. The Starting Early intervention increased tummy time and unrestrained floor time compared to controls. Attending a greater number of group sessions increased the intervention's impact. The intervention did not impact overall movement restricted time.

Few studies have described infant physical activity.23 This is likely because infant physical activity is difficult to measure and recommendations for how to promote activity are scarce.23,24 Many families are not aware of recommendations and the negative health impacts of limited tummy time.10,11 While the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends caregivers place infants on solid surfaces to play, we found that little tummy time was happening on hard surfaces. We found that infants generally spent limited unrestrained floor time. These findings may reflect vagueness in these recommendations and concerns about safety. Mothers reported being worried about infants getting hurt, possibly by other children or insects and mice. Further research is needed to understand barriers to practicing tummy time on the floor and how they may be overcome by addressing parent concerns about housing crowdedness or vermin. If the goals of infant physical activity recommendations are to promote motor development and future activity, studies are needed to understand if tummy time on an adult's lap or chest, which may actually limit infant movement, has the same impact as being on the floor. Further research is needed to compare energy expenditure of these different activities, given that it remains unclear whether an infant in a supine position could expend more energy with limb movements than a prone infant with more large muscle movements.

While the relations between infant activity and growth remain unclear, studies are beginning to demonstrate beneficial effects on later activity and weight. Tummy time is believed to build muscle, which may facilitate gross motor milestones.25,26 Higher motor performance has been associated with frequent tummy time and lower performance with frequent sitting in devices.27 Earlier motor development may be related to future physical activity, specifically a greater frequency and variety of sports participation.28 Infants not placed regularly in prone or with short duration of prone positioning demonstrated lower motor development scores29 and the delayed milestones, such as rolling over and crawling.25,30 Frequent spontaneous kicking, likely increased during unrestrained floor time, has been associated with early walking.31 Longitudinal studies focused on movement quality are needed to understand the long-term effects on development. Lower infant physical activity has been associated with increased infant total body fat,15,16,32 rapid weight gain,17 overweight status,17 and greater skin fold thickness.18 Unrestricted movement time at age 9 months was inversely related to waist circumference z-score and change in weight-for-length z-scores between 9-24 months.9

Our study is one of the first to describe the use of infant movement restricting devices. Greater than half of the mothers reported using these devices for more than one hour a day, with bouncy seats being the most commonly used. These parenting practices are likely to persist. One study showed that the overall time spent in movement restricting devices increased between infant ages 4 and 9 months old and predicted time in these devices at age 20 months.3 Infants who spent more time in devices, tended to have lower infant motor development scores33 and delayed motor milestones.34 Further research is needed to understand the impact of using these devices on infant activity and growth.

Understanding of the factors associated with infant activity is needed. Consistent with previous studies, we found that inadequate health literacy was related to lower tummy time.8 Health literacy was related to activity on the floor, as opposed to any location. Reasons for these differences and their health implications remain unclear and studies are needed to explore barriers to increasing tummy time among parents with lower health literacy. Active role modeling and practicing of skills may be needed to promote tummy time in parents with low health literacy. Plain language picture-based messaging may help to reinforce these lessons. Although health literacy was not found to be a potential moderator of intervention effect, interaction analyses may have been underpowered to detect this. We also found that country of origin was related to activity. US born mothers were more likely to practice any tummy time than non-US born mothers. These results are consistent with studies of older children showing that immigrant Hispanic children are more likely to be inactive compared with US born white and Hispanic children.35 Parents of overweight Hispanic children have been shown to provide less support for their children to engage in physical activity, perhaps a parenting practice that begins during infancy.36 US born mothers, however, were more likely to use movement restricting devices, which may reflect cultural or economic differences. Since US born mothers reported practices that promote and restrict infant activity, additional study is needed to understand the relative implications of these practices.

The majority of early obesity prevention interventions have focused on infant feeding. Only a few have reported impacts on infant activity. One Australian intervention study to promote healthy habits using pre-existing social groups, showed no differences in physical activity.37 Another intervention study comprised of home visits found that at age 6 months, the intervention group had higher rates of daily tummy time and began tummy time earlier.6 Parental engagement and role-modeling have been shown to improve Hispanic children's physical activity.38 Starting Early was likely successful in promoting tummy time and floor time through role modeling, active practicing of skills and building social networks. The effects were found to be dose-related, with improved impacts on activity with increased NPSG attendance.

This study has several limitations. Infant activity was based on maternal report and not observational instruments, which can be subject to recall and social desirability biases. However, studies that have documented differences in maternal report and actometer measures of infant activity, found that measured activity may be confounded by caregiver movement and handling of the infant.39 Although Starting Early had positive impacts on tummy time and floor time, it did not alter the use of movement restricting devices. While the NPSG included discussions about limiting movement restricted time, they did not incorporate active modeling of how to limit these devices. Future modifications of the program will aim to incorporate this. It is also difficult to disentangle which specific components of the multi-component intervention led to impacts on tummy time. Infant motor development was not collected at this follow-up assessment. Finally, participating mothers were low-income Hispanic women, limiting our generalizability to other populations.

Conclusion

Tummy time and unrestrained floor time are uncommon daily practices in low-income Hispanic families. Use of movement restricting devices is widespread. Infant activity was lower among immigrant mothers and those with inadequate health literacy, and use of devices was more common among US born mothers. The Starting Early intervention increased infant tummy time and floor time but did not impact movement restricted time. Longitudinal research is needed to determine relations between infant activity, motor development, childhood physical activity and growth. Primary care-based early child obesity prevention interventions have the potential to promote infant activity. Follow-up of this cohort will allow for analyses of long-term program impacts on infant activity, growth trajectories and obesity.

What is already known about this subject?

The Institute of Medicine's recommendations on early obesity prevention from birth to five years old stress the need to increase infant physical activity and to reduce the time infants spend in movement restricting devices.

Few studies have described infant activities, such as tummy time, unrestrained floor time and the use of movement restricting devices, in very young infants.

Promotion of healthy infant physical activity is rarely part of comprehensive early child obesity prevention programs that target high-risk families.

What does your study add?

Mothers reported low rates of tummy time and unrestrained floor time and high rates of time in movement restricting devices.

Inadequate health literacy was associated with low tummy time and unrestrained floor time, even after controlling for maternal education.

“Starting Early”, a primary care-based child obesity prevention program, led to increased reported tummy time and unrestrained floor time, and participating in more sessions had greater impact.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Starting Early staff: Ana Blanco, Lisa Lanza, Janneth Bancayan, Kenny Diaz, Stephanie Gonzalez, Christopher Ramirez and Jessica Rivera.

Funding: All phases of this study were supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2011-68001-30207. Funding was also provided by the National Institute of Health / National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH/NICHD) through a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23HD081077; PI Gross).

Footnotes

Clinical trial registration: This study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov, Trial registry name: Starting Early Obesity Prevention Program; ID number: NCT01541761. URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01541761

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions: RG, AM, HY, ST, MM conceptualized and designed the study. RG, MG, RS, MM coordinated and supervised data collection. RG, AM, RS, MM analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

References

- 1.McGuire S. Adv Nutr (Bethesda) 1. Vol. 3. Washington, DC: The national academies press; 2012. Institute of medicine (IOM) early childhood obesity prevention policies; pp. 56–57. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hnatiuk J, Salmon J, Campbell KJ, Ridgers ND, Hesketh KD. Early childhood predictors of toddlers' physical activity: Longitudinal findings from the Melbourne InFANT program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:123. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesketh KD, Crawford DA, Abbott G, Campbell KJ, Salmon J. Prevalence and stability of active play, restricted movement and television viewing in infants. Early Child Dev Care. 2015;185(6):883–894. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soska KC, Adolph KE. Postural position constrains multimodal object exploration in infants. Infancy. 2014;19(2):138–161. doi: 10.1111/infa.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downing KL, Hnatiuk J, Hesketh KD. Prevalence of sedentary behavior in children under 2 years: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;78:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Flood VM. Effectiveness of an early intervention on infant feeding practices and “tummy time”: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):701–707. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrin EM, Rothman RL, Sanders LM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences associated with feeding- and activity-related behaviors in infants. Pediatr. 2014;133(4):e857–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin HS, Sanders LM, Rothman RL, et al. Parent health literacy and “obesogenic” feeding and physical activity-related infant care behaviors. J Pediatr. 2014;164(3):577–83.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sijtsma A, Sauer PJ, Stolk RP, Corpeleijn E. Infant movement opportunities are related to early growth--GECKO drenthe cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(7):457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koren A, Reece SM, Kahn-D'angelo L, Medeiros D. Parental information and behaviors and provider practices related to tummy time and back to sleep. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24(4):222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachry AH, Kitzmann KM. Caregiver awareness of prone play recommendations. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65(1):101–105. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.09100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, et al. First steps for mommy and me: A pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(8):1217–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hesketh KD, Campbell KJ, Salmon J, et al. The Melbourne infant feeding, activity and nutrition trial (InFANT) program follow-up. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders LM, Perrin EM, Yin HS, Bronaugh A, Rothman RL Greenlight Study Team. “Greenlight study”: A controlled trial of low-literacy, early childhood obesity prevention. Pediatr. 2014;133(6):e1724–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tennefors C, Coward WA, Hernell O, Wright A, Forsum E. Total energy expenditure and physical activity level in healthy young Swedish children 9 or 14 months of age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(5):647–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson B, Henriksson H, Lof M, Hannestad U, Forsum E. Body-composition development during early childhood and energy expenditure in response to physical activity in 1.5-y-old children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(3):567–573. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts SB, Savage J, Coward WA, Chew B, Lucas A. Energy expenditure and intake in infants born to lean and overweight mothers. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):461–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802253180801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells JC, Ritz P. Physical activity at 9-12 months and fatness at 2 years of age. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13(3):384–389. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Gross MB, Scheinmann R, Messito MJ. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based child obesity prevention intervention on infant feeding practices. J Pediatr. 2016;174:171–177.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among U.S. adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994) Obes Res. 1997;5(6):542–548. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adolph K, Cole W, Komati M. How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and dozens of falls per day. Psychol Sci. 2012;23:1387–1394. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamin Neelon SE, Oken E, Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW. Age of achievement of gross motor milestones in infancy and adiposity at age 3 years. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1015–1020. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0828-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo Y, Liao H, Chen P, Hsieh W, Hwang A. The influence of wakeful prone positioning on motor development during the early life. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(5):367–376. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181856d54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slining M, Adair LS, Goldman BD, Borja JB, Bentley M. Infant overweight is associated with delayed motor development. J Pediatr. 2010;157(1):20–25.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Kegel A, Peersman W, Onderbeke K, Baetens T, Dhooge I, Van Waelvelde H. New reference values must be established for the Alberta infant motor scales for accurate identification of infants at risk for motor developmental delay in Flanders. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(2):260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridgway CL, Ong KK, Tammelin TH, Sharp S, Ekelund U, Jarvelin MR. Infant motor development predicts sports participation at age 14 years: Northern Finland birth cohort of 1966. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennings JT, Sarbaugh BG, Payne NS. Conveying the message about optimal infant positions. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2005;25(3):3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pin T, Eldridge B, Galea MP. A review of the effects of sleep position, play position, and equipment use on motor development in infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(11):858–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich BD, Ulrich DA. Spontaneous leg movements of infants with Down syndrome and nondisabled infants. Child Dev. 1995;66(6):1844–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R, O'Connor L, Buckley D, Specker B. Relation of activity levels to body fat in infants 6 to 12 months of age. J Pediatr. 1995;126(3):353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott AL, Bartlett DJ. Infant motor development and equipment use in the home. Child Care Health Dev. 2001;27(3):295–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2001.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulrich DA, Hauck JL. Programming physical activity in young infants at-risk for early onset of obesity. Kinesiology Review. 2013;2:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutfiyya MN, Garcia R, Dankwa CM, Young T, Lipsky MS. Overweight and obese prevalence rates in African American and Hispanic children: An analysis of data from the 2003-2004 national survey of children's health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(3):191–199. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.03.070207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elder JP, Arredondo EM, Campbell N, et al. Individual, family, and community environmental correlates of obesity in Latino elementary school children. J Sch Health. 2010;80(1):20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell KJ, Lioret S, McNaughton SA, et al. A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity risk behaviors: A randomized trial. Pediatr. 2013;131(4):652–660. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson CB, Hughes SO, Fuemmeler BF. Parent-child attitude congruence on type and intensity of physical activity: Testing multiple mediators of sedentary behavior in older children. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):428–438. doi: 10.1037/a0014522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worobey J, Vetrini NR, Rozo EM. Mechanical measurement of infant activity: A cautionary note. Infant Behav Dev. 2009;32(2):167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]