Abstract

Background

High weight gain in pregnancy has been associated with child adiposity, but few studies have assessed the relationship across childhood or in racially/ethnically diverse populations.

Objectives

To test if weight gain in pregnancy is associated with high birthweight and overweight/obesity in early, middle, and late childhood, and whether these associations differ by maternal race/ethnicity.

Methods

7539 mother-child dyads were included from NLSY79: a nationally representative cohort study in the U.S. (1979–2012). Log-binomial regression models were used to analyze associations between GWG and the outcomes: high birthweight (> 4000 g) and overweight/obesity at ages 2–5 years, 6–11 years, and 12–19 years.

Results

Excessive weight gain was positively associated and inadequate weight gain was negatively associated with high birthweight after confounder adjustment (P < 0.05). Only excessive weight gain was associated with overweight in early, middle, and late childhood. These associations were not significant in Hispanics or blacks, although racial/ethnic interaction was only significant ages 12–19 years (P = 0.03).

Conclusions

Helping pregnant women gain weight within national recommendations may aid in preventing overweight and obesity across childhood, particularly for non-Hispanic white mothers.

Keywords: obesity, pediatric obesity, weight gain, fetal macrosomia

Introduction

Overweight and obesity disproportionately affect children who are non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, with national prevalence estimates in 2- to 19-year-olds of 35.2% in blacks and 38.9% in Hispanics, compared to 28.5% in non-Hispanic whites.1 The causes of child overweight/obesity and racial/ethnic disparities are complex and include preconception, prenatal, and early life exposures.2–4 One possible contributing factor is excessive gestational weight gain (GWG)—gaining more weight in pregnancy than is needed to support fetal development.5–7

Concerns about the rising prevalence of obesity in mothers and children led the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to revise its recommendations in 2009 to include specific, limited GWG ranges for overweight and obese women.5 However, there have been mixed findings regarding how weight gain above the IOM guidelines is related to child overweight and few studies have been conducted in racially/ethnically diverse populations.6,7 Only four out of 23 studies in a 2014 systematic review on GWG and child obesity included women of Hispanic origin.7 Studies on GWG and child obesity have been further limited by short follow-up periods, small study populations, and data collection periods before the prevalence of obesity increased nationally.8–14

This study aims to add to the understanding of the consequences of GWG on child overweight and obesity by using data from a nationally representative cohort study to test: (1) if GWG is associated with high birthweight and overweight or obesity in early, middle, and late childhood, and (2) whether associations between GWG and the child weight outcomes differ by maternal race/ethnicity.

Methods

Study Sample

This study used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), an ongoing cohort study designed to represent the U.S. population aged 14 to 21 years old in 1979. The study enrolled 12,686 youths, and also began enrolling the biological children of female study participants in 1986. More detailed information on these studies is available elsewhere.15

Information was collected on 4932 mothers and 11,512 children from 1979–2012. Mother-child dyads were eligible for this study if the child was born during or after 1979 as a full-term (≥ 37 weeks gestation) singleton, for a total of 4307 mothers and 7872 children. Preterm and multiple births were excluded to apply the IOM gestational weight gain recommendations appropriately. Eligible dyads were included in the final study sample if they had complete information to calculate GWG and at least one of the outcomes of interest, for a total of 4184 mothers and 7539 children. This study was approved by the University of California, Berkeley Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Measures

The exposure of interest was gestational weight gain, categorized as inadequate, adequate, or excessive following IOM guidelines specific to prepregnancy BMI categories.5 Mothers self-reported their prepregnancy height and weight and delivery weight in the first survey following pregnancy. We regression-calibrated the prepregnancy height data using error data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. To assess the reliability of recalled prepregnancy weight, our study team previously compared the prepregnancy weight data to the weight reported at the closest previous survey prior to that pregnancy and found they were similar.16

The four outcomes of interest were high birthweight (> 4000 g) and ever overweight or obese in early, middle, and late childhood (ages 2–5 years, 6–11 years, and 12–19 years, respectively). Birthweight was reported by the mother in the first survey following pregnancy. Child BMI values were calculated using weight and height measurements that were either made in person by trained study interviewers (74% of weight and 82% of height measurements) or were reported by the mother. Child BMI values were categorized based on International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) age- and sex-specific cut-off criteria for childhood overweight and obesity.17 Age groups were selected in accord with national child BMI surveillance methods.1 All outcomes were binary variables.

Because the outcomes could be assessed under different definitions, we conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses: (1) using very high birthweight (> 4500 g) and child obesity (IOTF definition)17 as outcomes, and (2) using U.S. CDC definitions for childhood overweight and obesity. We used the U.S. CDC growth charts and accompanying SAS program to calculate age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles to then categorize overweight and obesity following the CDC definitions.

Potential confounding variables were identified a priori based on the literature.8–12,18 These characteristics were reported either for the time of birth or the time of the first postpartum interview and included: maternal race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white/other, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic), prepregnancy BMI category (underweight: <18.5 kg/m2, normal weight: 18.5–25.9 kg/m2, overweight: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, obese: ≥ 30 kg/m2), parity (primiparous or multiparous), marital status (married or unmarried), education level (less than high school, high school graduate, college graduate), employment status (unemployed or < 10 h per week, part-time employment 10–34 h per week, full-time employment ≥ 35 h per week), household income (equivalized in year 2000 U.S. dollars and accounting for household size), age at birth of child (calculated from maternal and infant birth dates), smoking status during pregnancy (yes or no), and child’s year of birth (< 1980, 1980–1990, > 1990). Maternal race/ethnicity was also considered a priori as a possible effect measure modifier of the association between gestational weight gain category and the outcomes.19–21 The racial/ethnic categories were created by NLSY and include respondents who identified as African-American or non-Hispanic black as non-Hispanic black; those who identified as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish as Hispanic; and other races/ethnicities—comprised of approximately 90% whites—as non-Hispanic white/other.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses accounted for the complex sampling design (‘survey’ package in R)22 of NLSY79 by using clustered sampling information and standardized custom sampling weights. Variable distributions were estimated in the full study population and maternal race/ethnicity subpopulations. Differences in the variable distributions by race/ethnicity were assessed by Rao and Scott X2 tests (‘svychisq’) for categorical variables and linear regression models (‘svyglm’) for continuous variables. The distributions of sociodemographic variables were also compared across outcome groups to detect any patterns in the missingness of child BMI information.

The relationships between GWG category and the outcome variables were analyzed using log-binomial regression models (‘svyglm’). The models accounted for the complex survey design and family-level clustering. First, unadjusted models were used to estimate risk ratios for the bivariate relationships between GWG category and the outcome variables. Next, multivariable models, adjusting for all confounders (including race/ethnicity), were conducted to estimate adjusted risk ratios. Main effect estimates were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. We used multiple imputation by chained equations (‘mice’ package in R)23 in all multivariable models to account for missing values of the covariates: education, marital status, employment, smoking status, and household income. Missingness of imputed covariates ranged from 0.3% to 13%. The multiple imputation procedure imputed datasets using a model that incorporated the outcome, GWG category, all covariates, and quintiles of the sampling weights (to remove selection bias).24

To detect effect measure modification by race/ethnicity, we then tested for two-way multiplicative interaction between GWG and race/ethnicity in the multivariable models using Wald tests. Finally, we further investigated effect modification by stratifying the multivariable regression models by race/ethnicity. As ad hoc analyses, we: (1) adjusted regression models only for race/ethnicity, (2) conducted models only for outcomes with measured weight and height, and (3) tested for effect modification by infant sex, birth year, and birthweight. Statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.1.25

Results

In the study population, 42.5% of women gained above and 27.4% gained below the IOM recommendations for gestational weight gain (Table 1). The maternal race/ethnicity makeup of children in the study sample was 58.1% non-Hispanic white/other, 25.3% non-Hispanic black, and 16.6% Hispanic. Mothers tended to be normal weight prepregnancy, multiparous, married, have a high school education, and have given birth between 1980 and 1990 at an average age of 26.9 years old (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mother-infant pairs in the study population (n = 7539)*.

| Variable | Total (n = 7539) | Non-Hispanic white/other (n = 4380) | Non-Hispanic black (n = 1906) | Hispanic (n = 1253) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational weight gain†, % | <0.001 | ||||

| Inadequate | 27.4 | 25.4 | 36.2 | 30.3 | |

| Adequate | 30.1 | 31.5 | 23.2 | 29.8 | |

| Excessive | 42.5 | 43.1 | 40.5 | 39.9 | |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, % | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight | 7.2 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 4.3 | |

| Normal weight | 65.9 | 66.8 | 61.6 | 64.8 | |

| Overweight | 17.1 | 16.1 | 19.9 | 22.6 | |

| Obese | 9.8 | 9.5 | 11.8 | 8.3 | |

| Primiparous, % | 41.1 | 42.6 | 35.9 | 36.4 | <0.001 |

| Mother married at birth, % (n = 7282)‡ | 78.4 | 83.6 | 35.4 | 70.2 | <0.001 |

| Maternal education at birth, % (n = 7267)‡ | <0.001 | ||||

| Less than high school completion | 16.7 | 12.6 | 26.5 | 38.3 | |

| High school graduate | 63.8 | 63.8 | 65.8 | 54.3 | |

| College graduate | 20.0 | 23.5 | 7.7 | 7.4 | |

| Maternal employment at birth, % (n = 7376)‡ | <0.001 | ||||

| Unemployed | 35.7 | 31.6 | 47.5 | 44.5 | |

| Part-time employment | 28.8 | 29.2 | 24.9 | 25.9 | |

| Full-time employment | 37.4 | 39.2 | 27.6 | 29.6 | |

| Equivalized household income at birth, mean ± SD (n = 6493)‡ | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 10.1 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 9.4 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Child birth year, % | <0.001 | ||||

| <1980 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 13.4 | 10.6 | |

| 1980–1990 | 59.6 | 57.6 | 67.1 | 65.0 | |

| >1990 | 32.3 | 35.5 | 19.4 | 24.4 | |

| Maternal age at birth, y, mean ± SD | 26.9 ± 5.3 | 27.5 ± 5.2 | 24.9 ± 5.2 | 25.8 ± 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Mother smoked during pregnancy, % (n = 7 599)‡ | 27.0 | 28.0 | 27.7 | 13.8 | <0.001 |

Sample sizes are unweighted and descriptive statistics are weighted for the survey design.

Gestational weight gain categories defined by Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines.5

Sample sizes < 7539 reflect missing data for the specified variable.

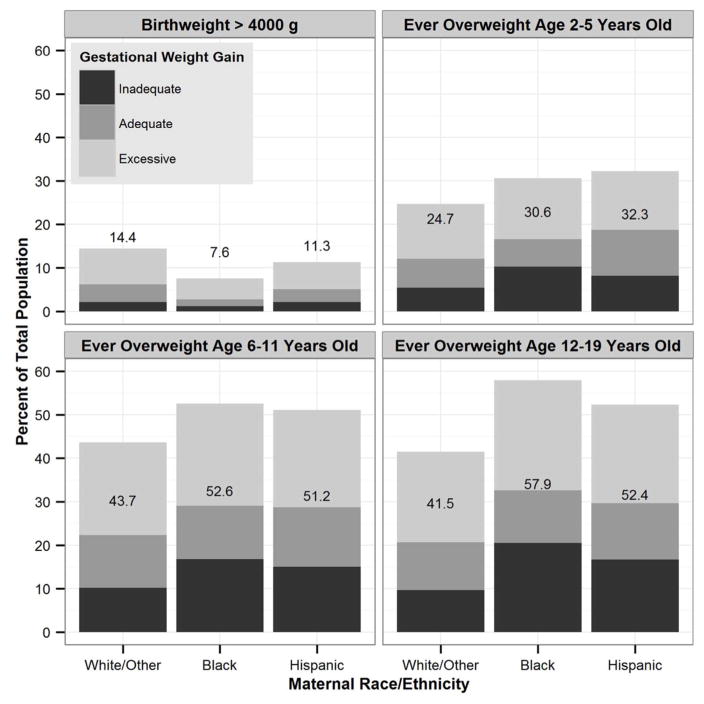

The distributions of GWG category, child weight outcomes, and all covariates differed significantly (P < 0.05) among maternal racial/ethnic groups (Table 1; Figure 1). Inadequate GWG was most prevalent in women who were black (36.2%) and excessive GWG was most prevalent in women who were white/other (43.1%)(Table 1). Black and Hispanic women, on average, were also more likely to be overweight or obese prepregnancy, multiparous, unmarried, have a lower education level, in lower income households, and younger than white/other women. High birthweight was less prevalent among children born to black or Hispanic mothers than children born to white/other mothers (Figure 1). However, overweight or obesity throughout childhood was more prevalent among children with black or Hispanic mothers than children with white/other mothers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence rates of birthweight > 4000 g and ever overweight or obese (IOTF criteria) ages 2–5 years, 6–11 years, and 12–19 years by gestational weight gain category among dyads with non-Hispanic white/other, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic mothers.

After adjusting for measured confounders, excessive GWG was associated with increased risk of high birthweight and overweight in 2- to 5-year-olds, 6- to 11-year-olds, and 12- to 19-year-olds in the total population (Table 2). Inadequate GWG was associated with a decreased risk of high birthweight, but not overweight in any age group (Table 2). Statistical interaction between GWG category and maternal race/ethnicity was not significant for high birthweight (P = 0.75), overweight in 2- to 5-year-olds (P = 0.17), or overweight in 6- to 11-year-olds (P = 0.39), but was significant for overweight in 12- to 19-year-olds (P = 0.03). After stratifying models by race/ethnicity, excessive GWG was associated with overweight in each age group in children with white/other mothers, but not in children with black or Hispanic mothers (Table 2). Excessive GWG was associated with high birthweight in children with white/other or black mothers, but not in children with Hispanic mothers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted* associations between gestational weight gain and child weight outcomes in the total study population and stratified by maternal race/ethnicity.

| Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Gestational weight gain† | Birthweight > 4000 g (n = 7304) | Ever overweight‡ 2–5 years old (n = 6142) | Ever overweight‡ 6–11 years old (n = 6095) | Ever overweight‡ 12–19 years old (n = 5748) |

| Total study population | Inadequate | 0.65 (0.50, 0.83) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.13) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.13) |

| Adequate | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |

| Excessive | 1.51 (1.23, 1.86) | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | |

| Non-Hispanic white/other | Inadequate | 0.66 (0.50, 0.88) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.16) |

| Adequate | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |

| Excessive | 1.52 (1.20, 1.92) | 1.22 (1.04, 1.44) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.31) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | Inadequate | 0.58 (0.32, 1.06) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.14) |

| Adequate | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |

| Excessive | 1.71 (1.07, 2.74) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.29) | 1.00 (0.89, 1.13) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) | |

| Hispanic | Inadequate | 0.65 (0.38, 3.24) | 0.84 (0.65, 1.09) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | 1.21 (1.02, 1.44) |

| Adequate | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |

| Excessive | 1.73 (0.93, 3.24) | 0.93 (0.76, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.91, 1.30) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.26) | |

P-values for interaction between gestational weight gain and race/ethnicity in association with outcomes: 0.75 for high birthweight, 0.17 for overweight 2–5 years old, 0.39 for overweight 6–11 years old, and 0.03 for overweight 12–19 years old.

Models adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI, parity, maternal marital status, maternal education, maternal employment, equivalized household income,20 infant birth year, maternal age, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Total population estimates are also adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity.

Gestational weight gain categories defined by Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines.5

Overweight includes obese following International Obesity Task Force sex- and age-specific BMI cut-off criteria.18

In analyses unadjusted for confounders, the strength of the associations between GWG and high birthweight did not change (Supporting Information Table S1). Effect estimates for excessive GWG and child overweight outcomes were further from the null in unadjusted analyses. Additionally, unadjusted associations were significant between excessive GWG and overweight in 2- to 5-year-olds (P = 0.03) and 12- to 19-year-olds (P = 0.01) with black mothers and between excessive GWG and overweight in 6- to 11-year-olds (P = 0.04) and 12- to 19-year-olds (P = 0.01) with Hispanic mothers. There were no meaningful changes to the unadjusted results after adjusting only for maternal race/ethnicity (Table S1).

Effect estimates and racial/ethnic differences were similar, standard errors were larger, and interactions were not significant in sensitivity analyses that used child obesity as the outcome (Supporting Information Figure S1 and Tables S2–S3). Effect estimates using very high birthweight (> 4500 g) were unstable because of low prevalence. In sensitivity analyses using U.S. CDC definitions of child overweight and obesity, there were no meaningful changes to the results (Supporting Information Tables S4–S7). There were also no significant differences found in post hoc analysis of outcomes with measured weight and height (Supporting Information Table S8) or in testing of effect modification by infant sex, birth year, or birthweight (results not shown).

Discussion

In this nationally representative study in the United States, gestational weight gain above the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations was related to increased risk of high birthweight and overweight in early, middle, and late childhood. The association between excessive GWG and child overweight was only significant in non-Hispanic whites/others after stratifying by maternal race/ethnicity, although this interaction was only significant in late childhood. The results of this study suggest that ‘overnutrition’ in pregnancy independently affects child body composition throughout child development, particularly in non-Hispanic whites.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to analyze the relationship between GWG and overweight/obesity throughout childhood in a racially/ethnically diverse sample and to assess effect modification by maternal race/ethnicity. Weight status was assessed in four age groups (birth, 2- to 5-year-olds, 6- to 11-year-olds, and 12- to 19-year-olds) to capture possibly differential effects following catch-up growth in infancy, the adiposity rebound, and puberty.3 In taking this approach, we found the association between excessive GWG and overweight to be relatively consistent—at increased risks of 10 to 16 percent—in the three age groups. Rooney et al.8 had similar findings in a smaller, more homogenous population, in which the odds ratios for the associations between excessive GWG (using IOM 1990 guidelines) and child overweight or obesity were 1.73 in 4–5 year olds, 2.11 in 19–20 year olds, and 2.21 in 19–20 year olds. Prior evidence suggests that the obesogenic effects of shared behaviors and environments between mothers and offspring may be persistent or even become more pronounced over childhood.26 Consistently strong associations across age groups may also reflect children who are overweight in early childhood staying overweight throughout childhood. There are discrepancies in the literature, however, as Schack-Nielsen et al.11 found the association between GWG and offspring BMI z-score to decrease after middle childhood in a Danish birth cohort. Our study’s results may differ from those of Schack-Nielsen because of differences in sample composition, design, and analysis, but we cannot know with certainty.

Very few studies on GWG and child adiposity have included a substantial number of black and Hispanic women.6,7 However, black and Hispanic women are more likely than white women to gain inadequate weight in pregnancy and to deliver infants with low birthweights.19,27 Correspondingly, white women are more likely than black and Hispanic women to gain excessive weight in pregnancy and to deliver infants with high birthweights.19,27 By age 2, however, children of black or Hispanic mothers are more likely to be overweight or obese than children of white mothers.1,4,20 Our results corroborate these previous findings regarding GWG and birthweight. Furthermore, GWG was not meaningfully related to child overweight at any age in dyads with black or Hispanic mothers in our study.

Our findings may be partially explained by racial/ethnic differences in the determinants of childhood overweight and obesity. Taveras et al.21 found that, compared to prenatal factors (including excessive GWG), exposures in infancy and early childhood explained most of the study population’s racial/ethnic differences in BMI z-score at age 7.21 Although weight gain in pregnancy may have epigenetic effects on offspring metabolism, the obesogenic early life experiences and environments of black and Hispanic children may overshadow such effects.5,28 Efforts to prevent child obesity, therefore, should be comprehensive—targeting obesogenic behaviors and environments both before and after birth.

Some aspects of the NLSY79 limit the results of this study. We were unable to consider the role of several unmeasured covariates, including diet, physical activity, gestational diabetes, and child pubertal status. With the exception of most child weight and height measurements, all data were reported by the mother. Self-reporting likely resulted in some misclassification of GWG and prepregnancy BMI, but prior bias analyses suggest bias would be minimal and our study team previously found the self-reported weight measurements to be reliable.16,29,30 Additionally, NLSY collected child weight and height measurements from 1986 to 2012, resulting in measurements not being recorded at certain ages if a child was born close to the beginning or end of the study period. We were, therefore, unable to assess weight-for-length in children under 2 years old. Inconsistent follow-up information in the children also prevented us from conducting within-child longitudinal analyses across all of the survey rounds.

The nationally representative design of the NLSY79 supports generalizability of this study’s results to the racially/ethnically diverse population of children whose mothers were adolescents and living in the U.S. in 1979. The NLSY79 also collected extensive data over 33 years, allowing the analysis of the relationship between GWG and weight status at different stages of child development and the adjustment of many potential confounding factors that were assessed before or close to the time of birth. Additionally, the prospective study design enabled the use of risk ratios as effect estimates, which more accurately capture the risk associated with GWG than the odds ratio estimates frequently used in related studies. Our findings of adjusted risk ratios between 1.10 and 1.16 for the associations between excessive GWG and childhood overweight or obesity are consistent with odds ratios reported in previous studies, including a combined odds ratio of 1.38 [95% CI 1.21, 1.57] found for the association in a recent meta-analysis.6

Gestational weight gain is an important determinant of optimal health for mothers and children and better management of weight gain in pregnancy is a potentially effective public health intervention. This study’s results suggest that helping women in the U.S. meet the IOM guidelines for gestational weight gain could help prevent the development of overweight and obesity in childhood, particularly in non-Hispanic whites. However, weight gain in pregnancy may be a less important determinant of childhood obesity in blacks and Hispanics. These findings underscore the need to further examine the complex causes of maternal and child obesity and racial/ethnic differences to inform effective interventions.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject

Gaining excessive weight in pregnancy may contribute to child overweight and obesity.

Overweight and obesity in the United States disproportionately affect children who are non-Hispanic black or Hispanic.

What this study adds

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy was associated with child overweight and obesity from ages 2 to 19 years old in a nationally representative, prospective study sample, particularly in non-Hispanic whites.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health grant #R01MD006014. Dr. Rehkopf is supported by the National Institute of Aging (K01AG047280). SAL and LCP designed the study and conducted the data analysis and interpretation. SAL also conducted the literature search, generated the figures, and wrote the manuscript. DHR, LDR, and BA conceptualized the study, supervised the data analysis, and contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

BA has received personal fees as a reviewer for UpToDate. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oken E, Gillman MW. Fetal origins of obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:496–506. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weden MM, Brownell P, Rendall MS. Prenatal, perinatal, early life, and sociodemographic factors underlying racial differences in the likelihood of high body mass index in early childhood. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2057–2067. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain during Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nehring I, Lehmann S, Von Kries R. Gestational weight gain in accordance to the IOM/NRC criteria and the risk for childhood overweight: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau EY, Liu J, Archer E, Mcdonald SM, Liu J. Maternal weight gain in pregnancy and risk of obesity among offspring: a systematic review. J Obes. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/524939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooney BL, Mathiason MA, Schauberger CW. Predictors of obesity in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in a birth cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15 doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sridhar SB, Darbinian J, Ehrlich SF, et al. Maternal gestational weight gain and offspring risk for childhood overweight or obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:259.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margerison-Zilko CE, Shrimali BP, Eskenazi B, Lahiff M, Lindquist AR, Abrams BF. Trimester of maternal gestational weight gain and offspring body weight at birth and age five. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1215–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schack-Nielsen L, Michaelsen K, Gamborg M, Mortensen E, Sørensen T. Gestational weight gain in relation to offspring body mass index and obesity from infancy through adulthood. Int J Obes. 2010;34:67–74. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrotniak BH, Shults J, Butts S, Stettler N. Gestational weight gain and risk of overweight in the offspring at age 7y in a multicenter, multiethnic cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1818–1824. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diesel JC, Eckhardt CL, Day NL, Brooks MM, Arslanian SA, Bodnar LM. Is gestational weight gain associated with offspring obesity at 36 months? Pediatr Obes. 2015;10:305–310. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriksson P, Eriksson B, Forsum E, Löf M. Gestational weight gain according to Institute of Medicine recommendations in relation to infant size and body composition. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10:388–394. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR) NLSY79 User’s Guide. The Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranchod YK, Headen IE, Petito LC, Deardorff JK, Rehkopf DH, Abrams BF. Maternal childhood adversity, prepregnancy obesity, and gestational weight gain. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Peters H, Gama A, et al. Maternal smoking in pregnancy association with childhood adiposity and blood pressure. Pediatr Obes. 2015;11:202–209. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Headen IE, Davis EM, Mujahid MS, Abrams B. Racial-ethnic differences in pregnancy-related weight. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:83–94. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125:686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity: the role of early life risk factors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:731–738. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Softw. 2004;9:1–19.23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: http://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poston L. Maternal obesity, gestational weight gain and diet as determinants of offspring long term health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strutz KL, Richardson LJ, Hussey JM. Selected preconception health indicators and birth weight disparities in a national study. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:e89–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drake AJ, Reynolds RM. Impact of maternal obesity on offspring obesity and cardiometabolic disease risk. Reproduction. 2010;140:387–398. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM, Simhan HN, Diesel JC, Abrams B. The impact of exposure misclassification on associations between prepregnancy BMI and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obesity. 2010;18:2184–2190. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodnar LM, Siminerio LL, Himes KP, Hutcheon JA, Lash TL, Parisi SM. Maternal obesity and gestational weight gain are risk factors for infant death. Obesity. 2016;24:490–498. doi: 10.1002/oby.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.