ABSTRACT

Bordetella pertussis is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes respiratory infections in humans. Ongoing molecular surveillance of B. pertussis acellular vaccine (aP) antigens is critical for understanding the interaction between evolutionary pressures, disease pathogenesis, and vaccine effectiveness. Methods currently used to characterize aP components are relatively labor-intensive and low throughput. To address this challenge, we sought to derive aP antigen genotypes from minimally processed short-read whole-genome sequencing data generated from 40 clinical B. pertussis isolates and analyzed using the SRST2 bioinformatic package. SRST2 was able to identify aP antigen genotypes for all antigens with the exception of pertactin, possibly due to low read coverage in GC-rich low-complexity regions of variation. Two main genotypes were observed in addition to a singular third genotype that contained an 84-bp deletion that was identified by SRST2 despite the issues in allele calling. This method has the potential to generate large pools of B. pertussis molecular data that can be linked to clinical and epidemiological information to facilitate research of vaccine effectiveness and disease severity in the context of emerging vaccine antigen-deficient strains.

KEYWORDS: Bordetella pertussis, DNA sequencing, immunization, molecular methods, surveillance studies

INTRODUCTION

Bordetella pertussis is a Gram-negative aerobic bacterium that causes respiratory illness in humans and is commonly referred to as whooping cough. Vaccination is the primary recommended preventative public health intervention, and since the end of the 20th century, vaccination programs in most high-income countries have incorporated acellular component vaccines (aP) as replacements for whole-cell vaccines that have been used for over 60 years, largely due to an improved safety profile (1–5). The aP is the result of decades of research into the immunological properties of B. pertussis and its virulence factors using animal models and in vitro experiments to characterize B. pertussis's mode of infection and pathophysiological effects (6–8). In the context of large and frequent B. pertussis outbreaks and decreasing vaccine effectiveness since the introduction of the aP (albeit to various degrees in different regions), additional research has been conducted to examine how vaccination may be influencing the evolution of B. pertussis and the long-term impact on the effectiveness of B. pertussis vaccines (9–14).

Allele typing using select virulence factors has been useful in describing changes across larger evolutionary scales and has been a key tool for associating changes in the B. pertussis population with the introduction of aPs (15–17). The virulence factor typing scheme historically used for laboratory surveillance in Canada emphasizes Canadian acellular vaccine antigens and takes into account the historical epidemiology and serotyping results (18). The loci that make up this B. pertussis virulence factor typing scheme are ptxP (pertussis toxin promoter), ptxS1 (pertussis toxin subunit 1, also known as PtxA), fha (filamentous hemagglutinin), prn (pertactin), and fim3 (fimbria subunit 3). Of note, the fim2 gene is not included despite Fim2 being a component of the aP as more than 99% of strains serotyped in Canada were found to express only Fim3 (19). Ongoing surveillance of these antigens is critical to understanding the evolution of B. pertussis in response to widespread use of aP for effective disease control and eventual elimination.

Molecular biology-based laboratory methods used to characterize strains are often labor-intensive and relatively low throughput and frequently require redundant primers to account for variation in primer binding sites (20). Newer techniques, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS), avoid these issues and provide significant insight into B. pertussis strain evolution. However, some characteristics of the B. pertussis genome pose challenges to the use of short-read WGS technology. Mainly, assembly is hindered by the high GC content and numerous long repetitive insertion sequences. Resolution of these challenges traditionally used complex bioinformatics pipelines and hybrid assemblies with lower-throughput long-read sequencing technologies, which are not as amenable for routine laboratory-based surveillance of B. pertussis strains (10, 21). To address this, we propose using partially processed raw short-read sequence data to obtain the aP antigen information described above. This alternative approach to full-genome assembly emphasizes practicality over completeness of data extracted from WGS and may be more suitable for applications related to routine public health surveillance.

In this study, we sought to derive aP antigen genotypes from minimally processed short-read WGS data generated from clinical B. pertussis isolates. We selected 40 isolates from cases residing in Ontario, Canada, representing varied demographic and epidemiologic characteristics (age, immunization status, and outbreak link, per Table 1) and assessed the use of a short-read targeted alignment bioinformatics package, SRST2 version 0.1.5 (22), for describing Ontario B. pertussis strain variability. Select results were then compared to those derived from traditional (Sanger) sequencing. Additionally, results were analyzed in the context of epidemiological characteristics and historical strain typing data to assess the utility of this method for public health laboratory-based surveillance of B. pertussis vaccine antigens.

TABLE 1.

Number of Bordetella pertussis isolates sequenced by age group, immunization status, and outbreak association, September 2011 to December 2013, Ontario, Canada

| Age group (yr) | No. of isolates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak |

Sporadic |

Total | |||

| Immunized | Unimmunized | Immunized | Unimmunized | ||

| <1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| 1–5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 14 |

| 6+ | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 |

| Total | 8 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 40 |

RESULTS

SRST2 correctly identified virulence factor alleles for all loci compared to traditional sequencing with the exception of the prn allele. SRST2 failed to predict the correct allele for prn in 33/40 isolates. The WGS result was verified by Sanger sequencing, which showed that nearly all isolates (n = 39) possessed the prn-2 allele with the exception of one that was reported as prn-1. A summary of the prn alleles identified by SRST2 is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of prn alleles identified by SRST2 from whole-genome sequencing of 40 Bordetella pertussis clinical isolates, September 2011 to December 2013, Ontario, Canada

| prn allele identified | Allele GenBank accession no. | Flag(s)a (isolate count) | Total no. of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AJ011091 | SNP (2), indel (2), holes (1) | 2 |

| 2 | AJ011092 | None (4), truncation (3) | 7 |

| 3 | AJ011093 | None (1), truncation (7), indel (1) | 9 |

| 4 | AJ011015 | None (7), truncation (9), SNP (1), indel (1) | 17 |

| 5 | AJ011016 | None (1) | 1 |

| 13 | EF486277 | Holes (1) | 1 |

| 15 | JX100834 | None (1), SNP (1), indel (1) | 2 |

| 16 | KC981248 | Holes (1) | 1 |

Flags are defined as follows: none, reads aligned to reference with no differences; truncation, insufficient read depth on either side of a given base to confidently align it with other reads; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism detected where the majority of reads (minimum of 5) aligned at a given base pair do not match the reference; indel, the majority of aligned reads include inserted or deleted base pairs compared to the reference; holes, there are no reads covering a given base pair in the reference.

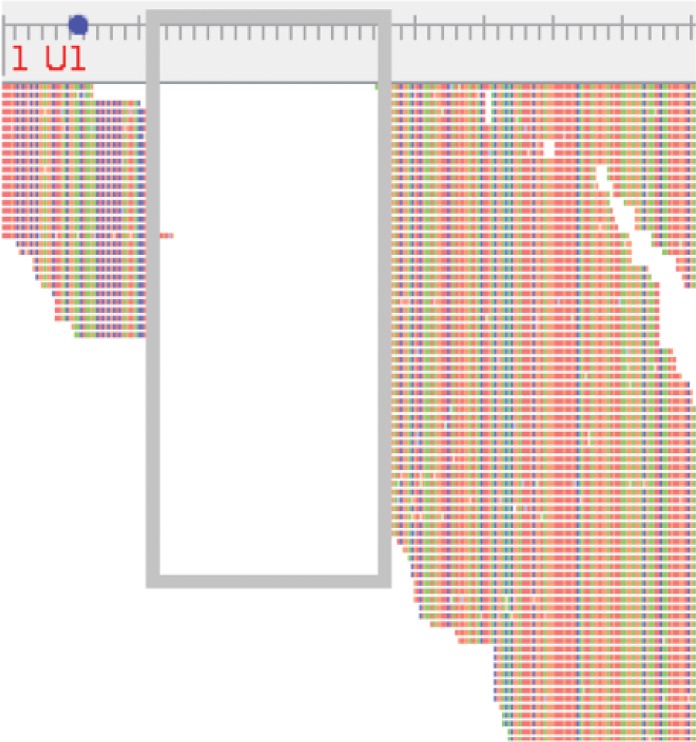

Analysis of the allele results obtained from SRST2 revealed very little variation in four of the five virulence factors investigated: fhaB, ptxP, ptxS1, and prn. All isolates had the genotype fhaB-1 ptxP-3 ptxS1-A prn-2 with the exception of one isolate from an immunized child, age range 1 to 5 years, which was not associated with an outbreak. The isolate from this child was identified as fhaB-1 ptxP-1 ptxS1-B prn-1, whereby the prn allele was also found to contain an 84-bp deletion between positions 25 and 109 similar to mutation VII as described by Pawloski et al. (23) and Otsuka et al. (24). Upon reviewing the alignment of WGS short reads against prn-1, we similarly found a large gap in the alignment compared to the reference (Fig. 1). Sufficient read coverage in this portion of the gene facilitated this observation, but manual confirmation of prn allele types was not possible due to insufficient coverage in the region of variation (bp 800 to 900) for all isolates.

FIG 1.

Reads from a clinical Bordetella pertussis isolate aligned to the prn-1 allele, as viewed in Tablet with an 84-bp deletion between positions 25 and 109 (gray box). The base pair ruler is scaled to 5 bp for minor gradations and 25 bp for major gradations. The start codon position is indicated on the base pair ruler by a blue dot.

Genotype variation was predominantly found in the fim3 locus whereby 17 of 40 (42.5%) isolates contained fim3-B, and the 23 remaining isolates (57.5%) had fim3-A. The proportion of Ontario isolates possessing the fim3-A allele during the study period was found to be significantly different (chi-square test, P < 0.001) than the previously reported proportion for isolates collected between 1998 and 2006 (87.9% fim3-B, 12.1% fim3-A, n = 520) (18). The distribution of these alleles stratified by age groups, vaccination status, and outbreak association is shown in Table 3. No significant association was found between the fim3 allele and the patient characteristics considered for this study (P ≥ 0.001). When all loci are considered together per the typing scheme described by Shuel et al. (18), the distribution of sequence types (STs) was determined as follows: ST-1, 17 isolates; ST-2, 22 isolates; and ST-11, 1 isolate (although the prn-1 allele was found to be a type VII mutant, and this region of the gene was not sequenced in the original study by Shuel et al. [18]).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of Bordetella pertussis fim3 alleles according to age group, immunization status, and outbreak association, September 2011 to December 2013, Ontario, Canada

| Patient attribute | fim3-A (%, n = 23) | fim3-B (%, n = 17) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (yr) | 0.604 | ||

| <1 | 17.5 | 7.5 | |

| 1–5 | 20.0 | 15.0 | |

| 6+ | 20.0 | 20.0 | |

| Immunization status | 0.491 | ||

| Immunized | 30.0 | 17.5 | |

| Unimmunized | 27.5 | 25.0 | |

| Outbreak association | 0.964 | ||

| Outbreak | 27.5 | 20.0 | |

| Sporadic | 30.0 | 22.5 |

As determined by the chi-square test.

DISCUSSION

The present study used a representative sample of 40 B. pertussis clinical isolates from patients residing in Ontario, Canada, to examine the feasibility of using short-read WGS and the SRST2 bioinformatics application as a proof of concept in laboratory surveillance of B. pertussis. Using this novel approach, we examined characteristics of circulating B. pertussis strains in Ontario and produced data that would have previously required a minimum of 200 amplifications and 2 × 200 sequencing assays for 40 isolates using traditional PCR-based Sanger sequencing methods. The high-throughput capability would facilitate the generation of retrospective data from historical isolate collections, providing baseline data for a laboratory surveillance program, and the method has the ability to quickly process large numbers of specimens associated with outbreaks.

Utilizing this new approach to B. pertussis sequence typing, we found a statistically significant difference in the proportion of isolates containing the two possible alleles of the fim3 gene compared to historical data (18). Additionally, we did not observe any significant associations between sequence types and patient characteristics, in contrast to a previous study regarding the association of ST-1 with unimmunized individuals in Alberta (25). This finding lends support to the authors' concern regarding potential biases in sample selection for their study, although the effect of the small sample size in our study cannot be ruled out. These brief examples highlight the potential benefits of short-read WGS for enhancing B. pertussis surveillance without the challenges of fully assembling B. pertussis genomes. The large number of repetitive IS481 mobile elements that are thought to play a role in shaping B. pertussis population evolution remains the most significant obstacle for rapidly assembling B. pertussis genomes from short-read WGS data (26). However, the permanent storage and versatility of short-read WGS data allow more in-depth analyses to be conducted as needed using more computationally complex methods (10).

Another advantage to this approach is that it does not rely on primer design—which is typically dependent on incomplete sequence databases that cannot anticipate future evolutionary changes to primer binding regions. For virulence factors in particular, it has been found that despite the low population genomic heterogeneity of B. pertussis, these regions are susceptible to higher rates of change than the rest of the genome (10). For example, numerous variations in the prn gene have led to the emergence of B. pertussis strains that do not express pertactin (PRN). A recent study, identified nine mutations spanning the entire gene that were associated with the loss of PRN expression in B. pertussis strains isolated between 2010 and 2012 (23). The changes to the prn coding and regulatory regions included single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions, inversions, and the insertion of the 1,048-bp insertion sequence IS481. Included among these mutations was the 84-bp deletion observed in one isolate in our study. Due to this variation, the characterization of prn in these isolates required 18 primers, compared to the initial characterization of prn in 1998 that required six (23, 27). Therefore, the final determination of these genotypes would require a labor-intensive process of elimination where initial attempts at amplification would fail and require troubleshooting with alternative primer combinations. Isolates included in our study were not found to contain any IS481-mediated disruptions of prn, in contrast to 8 of 12 isolates described by Tsang et al. (35), but selection bias and the small sample size of both studies are likely confounders. High-throughput characterization methodologies such as those described in this study and larger sample sizes would facilitate generating sufficient data to examine these phenomena more closely.

The most important limitation of our study related to the determination of prn alleles. SRST2 incorrectly identified the prn allele for 33 of the 40 clinical isolates assessed. The sequence structure of the prn allele is particularly difficult to assess by short-read WGS due to a variable region composed of a high-GC-content 15-bp repeat. The prn alleles 1 to 6 differ by the number of 15-bp repeats and the number of SNPs contained therein (28). The high GC content of this region decreases read coverage relative to the rest of the reference sequence, which in turn affects the ability of SRST2 to correctly align these few reads. This is particularly the case for the prn-2 allele, which possesses six repeats (second only to prn-9, which possesses a seventh inexact repeat) and is also the most common allele type that we identified in this study (found in 39 of 40 isolates). Greater numbers of repeats require more full-length reads aligned to accurately determine the correct consensus sequence for the allele. The seven isolates that were correctly identified as prn-2 by SRST2 had greater read depth in the repeat region than did the 33 other isolates. Variation in the initial DNA concentration of samples submitted for sequencing as well as internal WGS run conditions may lead to differential read depths. Optimizing sequencing conditions to yield maximum depth may overcome the issues with identification of prn alleles by SRST2, which is particularly important in the context of increasing numbers of isolates that do not express pertactin (21). Increasing the amount of DNA processed per library or running fewer libraries per flow cell may be helpful in this regard. Incremental improvements in short-read sequencing technologies may also alleviate these issues in future studies. Nevertheless, careful manual review of prn alignments should be supplemented with occasional Sanger sequencing and Western blot expression studies to confirm novel or ambiguous short-read WGS-based results to assess the effect on pertactin expression.

The development of short-read WGS and the associated bioinformatics tools have created an opportunity to improve traditional laboratory surveillance of B. pertussis. Analyses that would once require numerous PCRs and sequence reactions can now be accomplished by a single protocol; however, the shift of this workload from the wet lab to the in silico environment presents new challenges. Focusing on sequence information that is readily available and of direct relevance to public health such as aP antigens, important for understanding evolutionary changes by B. pertussis in response to vaccination, may mitigate computational expertise requirements normally associated with genome finishing. Additionally, these data are available for more comprehensive analyses of additional targets (e.g., antimicrobial resistance markers and new vaccine targets) or genome finishing and linkage with other data sets (e.g., clinical and epidemiological) to look at associations with patient outcome and vaccine effectiveness. These data may also prove useful for the development of future vaccines as evidenced by the reverse proteomics approach used for the meningococcal vaccine (29). The ongoing possibility of vaccine-induced selection pressure may make this approach particularly relevant for B. pertussis vaccine development.

The practical emphasis on the approach that we describe using SRST2 should facilitate studies of larger numbers of isolates to systematically examine the molecular underpinnings of B. pertussis pathogenesis. These large pools of molecular data linked to clinical and epidemiological information would bolster preliminary observations regarding vaccine effectiveness and disease severity in the context of emerging strains (13, 14, 21).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and DNA preparation.

Respiratory specimens submitted to the Public Health Ontario Laboratory for detection of B. pertussis were tested by real-time PCR as previously described (30). Specimens with cycle threshold (CT) values lower than 36 for B. pertussis were considered positive and set up in culture, whereas specimens with CT values of 36 to 40 and ≥40 were considered indeterminate and negative, respectively, and not cultured. Briefly, 100 μl of specimen in transport medium was plated on Regan-Lowe agar with cephalexin at 37°C for 7 days. Forty B. pertussis isolates were selected from all culture-positive specimens tested from 1 September 2011 through 31 December 2013 for which case investigation data were available (n = 357) in Ontario's Integrated Public Health Information System (iPHIS). Isolates were selected to adequately represent each category of age, immunization, and outbreak status as determined from iPHIS (Table 1), to assess the ability of WGS short reads to distinguish epidemiologically relevant characteristics. A complete description of the logic used for immunization status classification is provided in the supplemental material (see Fig. S1). DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (Life Technologies Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Whole-genome sequencing and data analysis.

Library preparation and WGS were performed at the University of Toronto's Donnelly Sequencing Centre. Extracted B. pertussis DNA (5 to 10 ng per isolate) was subjected to library preparation using the Illumina Nextera XT Library Prep kit per the manufacturer's instructions (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced as 150-bp paired-end reads on a single lane on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform using V4 chemistry and reagents (Illumina Inc.). aP antigen alleles were identified using the SRST2 bioinformatic package version 0.1.5 with primarily default parameters and inputs as described in the supplemental material (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) (22). Alignments for all alleles were manually reviewed for anomalies using SAMtools v0.1.18 and Tablet for visualization (31, 32).

PCR amplification.

PCR amplification for Sanger sequencing was performed on extracted genomic DNA (detailed above). Briefly, 1 μl of DNA lysate and 1 μl each of forward and reverse primers (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) were added to 10 μl of 2× HotStarTaq Plus master mix (Qiagen Inc.), 2 μl of 10× CL buffer, 2 μl of Q-Solution enhancer for GC-rich sequences, and 3 μl of molecular-grade water for a total reaction volume of 20 μl per well in a 96-well plate. Amplification was performed in a G-Storm GS1 thermocycler (G-Storm, Somerton, Somerset, United Kingdom) and included an initial activation step at 95°C for 10 min followed by a 35-cycle amplification program consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 54°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. This was followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplification was confirmed by running 4 μl of amplicon on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 2 μl of ethidium bromide at 110 V for 30 min alongside a 100-bp ladder (New England BioLabs, Whitby, ON, Canada).

Sanger sequencing and analysis.

WGS-derived results for the 5 allele targets were confirmed by Sanger sequencing for a subset of 8 isolates. For all targets except prn, PCR amplicons were sequenced on both strands using the same amplification primers (see Table S3) with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) per the manufacturer's instructions. Labeling was performed in a G-Storm GS1 (G-Storm, Somerton, Somerset, United Kingdom) thermocycler and included an initiation step at 96°C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 4 min. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed using the BigDye X Terminator purification kit (Applied Biosystems), following which samples were run on the ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Forward and reverse sequences were assembled using Vector NTI (Life Technologies, Inc.), and chromatographs for discrepant base calls were reviewed using FinchTV (Geospiza Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) (33). Sequencing of prn was performed for all isolates by the National Microbiology Laboratory (Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, MB, Canada) as previously described (23, 34).

Accession number(s).

WGS data for the 40 isolates were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information's Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession no. SRP094640.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals: the late Patrick Tang as well as Linda Miller and the members of the respiratory bacteriology department at Public Health Ontario Laboratory for their contributions to the isolation and handling of B. pertussis clinical isolates and Kathleen Whyte and Kristy Hayden at the National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, for their assistance with pertactin sequencing.

The views expressed in this work are solely those of the authors and do not reflect endorsement or approval by their respective organizations. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This project was funded by the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto (University of Toronto Fellowship to Alex Marchand-Austin), and Public Health Ontario. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02436-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). 2007. Statement on the recommended use of pentavalent and hexavalent vaccines. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). Can Commun Dis Rep 33:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheridan SL, Ware RS, Grimwood K, Lambert SB. 2012. Number and order of whole cell pertussis vaccines in infancy and disease protection. JAMA 308:454–456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litt DJ, Neal SE, Fry NK. 2009. Changes in genetic diversity of the Bordetella pertussis population in the United Kingdom between 1920 and 2006 reflect vaccination coverage and emergence of a single dominant clonal type. J Clin Microbiol 47:680–688. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01838-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe YJ, Park YJ, Jung C, Bae GR, Lee DH. 2012. National pertussis surveillance in South Korea 1955–2011: epidemiological and clinical trends. Int J Infect Dis 16:e850–e854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker MD, Edwards KM, Steinhoff MC, Rennels MB, Pichichero ME, Englund JA, Anderson EL, Deloria MA, Reed GF. 1995. Comparison of 13 acellular pertussis vaccines: adverse reactions. Pediatrics 96:557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gouw D, Diavatopoulos DA, Bootsma HJ, Hermans PW, Mooi FR. 2011. Pertussis: a matter of immune modulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35:441–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattoo S, Cherry JD. 2005. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:326–382. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melvin JA, Scheller EV, Miller JF, Cotter PA. 2014. Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis: current and future challenges. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:274–288. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, Chavez G. 2012. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr 161:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sealey KL, Harris SR, Fry NK, Hurst LD, Gorringe AR, Parkhill J, Preston A. 2015. Genomic analysis of isolates from the United Kingdom 2012 pertussis outbreak reveals that vaccine antigen genes are unusually fast evolving. J Infect Dis 212:294–301. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz KL, Kwong JC, Deeks SL, Campitelli MA, Jamieson FB, Marchand-Austin A, Stukel TA, Rosella L, Daneman N, Bolotin S, Drews SJ, Rilkoff H, Crowcroft NS. 2016. Effectiveness of pertussis vaccination and duration of immunity. CMAJ 188:E399–E406. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Cellès MD, Magpantay FMG, King AA, Rohani P. 2016. The pertussis enigma: reconciling epidemiology, immunology and evolution. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 283:20152309. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegerle N, Dore G, Guiso N. 2014. Pertactin deficient Bordetella pertussis present a better fitness in mice immunized with an acellular pertussis vaccine. Vaccine 32:6597–6600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safarchi A, Octavia S, Luu LDW, Tay CY, Sintchenko V, Wood N, Marshall H, McIntyre P, Lan R. 2015. Pertactin negative Bordetella pertussis demonstrates higher fitness under vaccine selection pressure in a mixed infection model. Vaccine 33:6277–6281. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooi FR, Van Der Maas NAT, De Melker HE. 2014. Pertussis resurgence: waning immunity and pathogen adaptation—two sides of the same coin. Epidemiol Infect 142:685–694. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuel M, Lefebvre B, Whyte K, Hayden K, de Serres G, Brousseau N, Tsang RSW. 2016. Antigenic and genetic characterization of Bordetella pertussis recovered from Quebec, Canada, 2002–2014: detection of a genetic shift. Can J Microbiol 62:437–441. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2015-0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Yao K, Ma X, Shi W, Yuan L, Yang Y. 2015. Variation in Bordetella pertussis susceptibility to erythromycin and virulence-related genotype changes in China (1970–2014). PLoS One 10:e0138941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuel M, Jamieson FB, Tang P, Brown S, Farrell D, Martin I, Stoltz J, Tsang RSW. 2013. Genetic analysis of Bordetella pertussis in Ontario, Canada reveals one predominant clone. Int J Infect Dis 17:e413–e417. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang RSW, Lau AKH, Sill ML, Halperin SA, Van Caeseele P, Jamieson F, Martin IE. 2004. Polymorphisms of the fimbria fim3 gene of Bordetella pertussis strains isolated in Canada. J Clin Microbiol 42:5364–5367. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5364-5367.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiden MCJ. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing of bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 60:561–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams MM, Sen KA, Weigand MR, Skoff TH, Cunningham VA, Halse TA, Tondella ML. 2016. Bordetella pertussis strain lacking pertactin and pertussis toxin. Emerg Infect Dis 22:319–322. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.151332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven LA, Schultz MB, Pope BJ, Tomita T, Zobel J, Holt KE. 2014. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 6:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawloski LC, Queenan AM, Cassiday PK, Lynch AS, Harrison MJ, Shang W, Williams MM, Bowden KE, Burgos-Rivera B, Qin X, Messonnier N, Tondella ML. 2014. Prevalence and molecular characterization of pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis in the United States. Clin Vaccine Immunol 21:119–125. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00717-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otsuka N, Han HJ, Toyoizumi-Ajisaka H, Nakamura Y, Arakawa Y, Shibayama K, Kamachi K. 2012. Prevalence and genetic characterization of pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis in Japan. PLoS One 7:e31985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmonds K, Fathima S, Chui L, Lovgren M, Shook P, Shuel M, Tyrrell GJ, Tsang R, Drews SJ. 2014. Dominance of two genotypes of Bordetella pertussis during a period of increased pertussis activity in Alberta, Canada: January to August 2012. Int J Infect Dis 29:e223–e225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowden KE, Weigand MR, Peng Y, Cassiday PK, Sammons S, Knipe K, Rowe LA, Loparev V, Sheth M, Weening K, Tondella ML, Williams MM. 2016. Genome structural diversity among 31 Bordetella pertussis isolates from two recent U.S. whooping cough statewide epidemics. mSphere 1:e00036-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00036-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mooi FR, Van Oirschot H, Heuvelman K, Van der Heide HGJ, Gaastra W, Willems RJL. 1998. Polymorphism in the Bordetella pertussis virulence factors P.69/pertactin and pertussis toxin in The Netherlands: temporal trends and evidence for vaccine-driven evolution. Infect Immun 66:670–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mooi FR. 2010. Bordetella pertussis and vaccination: the persistence of a genetically monomorphic pathogen. Infect Genet Evol 10:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Gregorio E, Rappuoli R. 2014. From empiricism to rational design: a personal perspective of the evolution of vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol 14:505–514. doi: 10.1038/nri3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guthrie JL, Robertson AV, Tang P, Jamieson F, Drews SJ. 2010. Novel duplex real-time PCR assay detects Bordetella holmesii in specimens from patients with pertussis-like symptoms in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Microbiol 48:1435–1437. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02417-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milne I, Stephen G, Bayer M, Cock PJA, Pritchard L, Cardle L, Shawand PD, Marshall D. 2013. Using Tablet for visual exploration of second-generation sequencing data. Brief Bioinform 14:193–202. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu G, Moriyama EN. 2004. Vector NTI, a balanced all-in-one sequence analysis suite. Brief Bioinform 5:378–388. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mooi FR, Hallander H, Wirsing Von König CH, Hoet B, Guiso N. 2000. Epidemiological typing of Bordetella pertussis isolates: recommendations for a standard methodology. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 19:174–181. doi: 10.1007/s100960050455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang RS, Shuel M, Jamieson FB, Drews S, Hoang L, Horsman G, Lefebvre B, Desai S, St-Laurent M. 2014. Pertactin-negative Bordetella pertussis strains in Canada: characterization of a dozen isolates based on a survey of 224 samples collected in different parts of the country over the last 20 years. Int J Infect Dis 28:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.