Abstract

Ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) are short α‐helices found in a number of eukaryotic proteins. UIMs interact weakly but specifically with ubiquitin conjugated to other proteins, and in so doing, mediate specific cellular signals. Here we used phage display to generate ubiquitin variants (UbVs) targeting the N‐terminal UIM of the yeast Vps27 protein. Selections yielded UbV.v27.1, which recognized the cognate UIM with high specificity relative to other yeast UIMs and bound with an affinity more than two orders of magnitude higher than that of ubiquitin. Structural and mutational studies of the UbV.v27.1‐UIM complex revealed the molecular details for the enhanced affinity and specificity of UbV.v27.1, and underscored the importance of changes at the binding interface as well as at positions that do not contact the UIM. Our study highlights the power of the phage display approach for selecting UbVs with unprecedented affinity and high selectivity for particular α‐helical UIM domains within proteomes, and it establishes a general approach for the development of inhibitors targeting interactions of this type.

Keywords: ubiquitin, phage display, protein engineering, ubiquitin interacting motif

Short abstract

Interactive Figure 2 | PDB Code(s): 5UCL

Abbreviations

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- GST

glutathione S‐transferase

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- UBD

ubiquitin binding domain

- Ub.wt

ubiquitin wild type

- UbV

ubiquitin variant

- UIM

ubiquitin interacting motif

- Vps27

Vacuolar protein sorting‐associated protein 27

Introduction

Ubiquitin (Ub) is a highly abundant 76‐amino acid protein that is expressed in every eukaryotic cell, and plays roles across a diverse range of cellular processes, including protein degradation,1 DNA damage repair,2, 3 cell cycle regulation4, 5 and a range of cell signaling pathways.6 Ub exerts biological effects through covalent attachment to substrate proteins, in a process known as ubiquitination, or through non‐covalent interactions with other proteins. Ubiquitination requires a coordinated cascade of reactions mediated by specialized enzymes (E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligating enzymes) to ultimately create an isopeptide bond between the C‐terminal glycine residue of Ub and a lysine or a peptide bond with the free amino terminus on the substrate protein. The ubiquitination cascade can also add Ub to one of seven lysines or the amino terminus within Ub itself to produce chains of various linkages. Distinct downstream effects are mediated by ubiquitination, depending on differences in the number of Ub moieties attached to a substrate and on the type of side‐chain linkages used when ubiquitin is iteratively attached to itself to form Ub chains.1, 7, 8 Alternatively, Ub can interact with other proteins in a non‐covalent manner through specialized Ub‐binding domains (UBDs) imbedded within many proteins. These non‐covalent interactions can facilitate the ubiquitination reaction itself or serve other regulatory roles.9

Hundreds of UBDs have been found imbedded in functionally diverse proteins, either alone or in combination with Ub enzymes or other UBDs.9, 10, 11 UBDs have been classified into over 20 structurally varied protein folds, which have been divided into five subfamilies: α‐helices, zinc finger (ZnF) domains, Ub‐conjugating like (Ubc‐like) domains, Plekstrin homology (PH) domains, and “others.”11, 12

The α‐helix subfamily is the largest, and it contains several distinct structural types, including Ub‐interacting motifs (UIMs), motifs interacting with Ub (MIUs), double‐sided UIMs (dUIMs), Ub‐associated (UBA) domains, coupling‐of‐Ub‐conjugation‐to‐endoplasmic reticulum degradation (CUE) domains, GGA and TOM (GAT) domains, and Vps/Hrs/STAM (VHS) domains.9, 12

Consisting of a single α‐helix of approximately 20 amino acids, UIMs represent the smallest of the helical UBDs,10 and they are widely distributed, with an estimated 12 or 60 UIMs predicted across 7 or 31 proteins in yeast and humans, respectively.13, 14 Despite their diminutive size and simple structure, UIMs have been implicated in many critical cellular pathways,12 including proteasomal degradation,15 endosomal sorting,16, 17 multivesicular body biogenesis,9, 18 DNA repair,19, 20 and DNA methylation.21 In most cases, UIMs recognize ubiquitinated proteins directly and many proteins that contain UIMs are themselves ubiquitinated in a UIM‐dependent manner.22, 23 UIMs conform to a consensus sequence of e‐e‐x‐x‐φ‐x‐x‐A‐φ‐x‐(φ/e)‐S‐z‐x‐e (where e is an acidic residue, φ is a hydrophobic residue, z is a bulky hydrophobic or polar residue with high aliphatic content, A is alanine, S is serine and x is a helix‐favoring residue).24 Numerous Ub‐UIM complex structures have been elucidated, revealing the basis for interaction.24, 25, 26 In particular, only ∼490 ± 90 Å2 or ∼470 ± 70 Å2 of surface area are buried by the interaction on the Ub and the UIM α‐helix, respectively (based on a comparison of the following PDB entries: 2MBH, 1Q0W, 2D3G and 1YX5), and the conserved alanine residue of the UIM packs against Ile44 of Ub at the centre of the interface. In addition to UIMs, at least 15 of the 20 families of UBDs rely on contacts with a hydrophobic patch centered on Ile44 of Ub,12, 27 with the same patch also being utilized in interactions with deubiquitinases (DUBs), E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligating enzymes.28, 29, 30 These interactions tend to exhibit only moderate affinities, which in the case of UBDs are typically in the high micromolar range.9, 10 This observation prompted our investigation into whether this oft‐used surface of Ub could be optimized to increase affinity and selectivity for specific binding partners.

We previously designed combinatorial phage‐displayed libraries of Ub variants (UbVs) in which we diversified a large surface of ∼2000 Å2 that included the Ile44 hydrophobic patch.31 These libraries proved to be remarkably fruitful in providing highly specific and potent UbVs that could target diverse Ub enzymes both in vitro and inside cells. Structural analysis of UbVs in complex with DUBs,31 HECT E3 ligases32 and SCF E3 ligases33 revealed the basis for improved affinity and stability, which depended on optimized interactions across large binding surfaces on UbVs ranging from 800 to 1900 Å2.

Here we extend this work to explore whether the same approach can be applied to the small binding surface on Ub that mediates low affinity interactions with UIM alpha‐helices. As a model system, we targeted the first of two UIMs in the yeast protein Vps27. We show that we can derive a UbV that binds to this UIM with an affinity that is improved almost 500‐fold compared with that of wild‐type Ub (Ub.wt). Moreover, the UbV exhibited high specificity for the cognate UIM relative to other yeast UIMs. We characterized the interaction between the UbV and UIM biochemically and structurally to understand the basis for enhanced affinity and specificity.

Results

UbV binders for the first UIM domain of Vps27

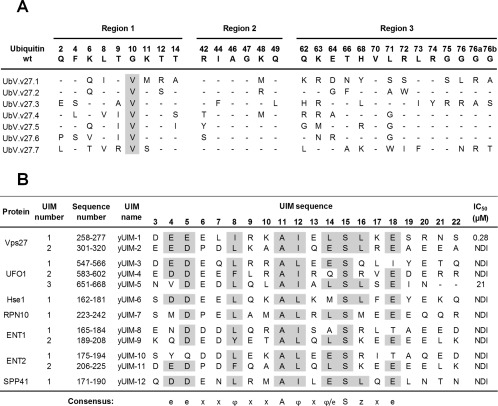

We used a biotinylated synthetic peptide representing the first UIM of the yeast protein Vps27 (yUIM‐1) as the bait for binding selections with “library 2,” a previously described phage‐displayed library of UbVs.31 Library 2 was constructed by a “soft randomization” strategy whereby 27 positions across a large surface including the Ile44 hydrophobic patch were diversified in a manner such that each position contained approximately 50% wild‐type sequence and 50% random mutations. Following five rounds of binding selections, individual phage clones were assessed for specific binding by phage ELISAs and clones that bound to the target peptide but not to streptavidin and several other negative control proteins were subjected to DNA sequence analysis, which revealed seven unique UbV sequences, all characterized by a common substitution of Val for Gly at position 10 [Fig. 1(A)]. Based on qualitative phage ELISAs, a specific UbV (named UbV.v27.1) that exhibited a strong ELISA signal for binding to peptide yUIM‐1 but not to a panel of other Ub‐associated proteins (data not shown) was chosen for detailed functional and structural characterization.

Figure 1.

Selective binding of UbV.v27.1 to yUIM‐1. (A) Sequence alignment of UbV.v27.1 and other UbVs selected for binding to yUIM‐1. The alignment shows only those positions that were diversified in the UbV library, and positions that were conserved as the wt sequence are shown as dashes. Sequences showing conservation across selected UbVs are highlighted in grey. (B) Sequence alignment of yeast UIMs and IC50 values for inhibition of UbV.v27.1 binding to immobilized yUIM‐1. Residues (arbitrarily numbered from 3 to 22) that conform to the UIM consensus are highlighted in grey, and the consensus is shown below (e is an acidic residue, φ is a hydrophobic residue, z is a bulky hydrophobic or polar residue with high aliphatic content, A is alanine, S is serine, and x is a helix‐favoring residue). “Sequence number” denotes the position of each UIM domain in the full‐length protein sequence according to the UniProt database.14 IC50 values were defined as the concentration of solution‐phase GST‐UIM fusion protein that inhibited 50% of the UbV.v27.1 binding to immobilized yUIM‐1. “NDI” denotes “no detectable inhibition” with 60 µM GST‐UIM.

Affinity and specificity of UbV.v27.1

To assess the affinity and specificity of UbV.v27.1, we measured affinities for all the yeast UIMs by competitive phage ELISAs. We purified each of the 12 yeast UIMs as fusions with the carboxy terminus of GST and used serial dilutions of each of these fusion proteins as competitors for the interaction of immobilized yUIM‐1 with solution‐phase, phage‐displayed UbV.v27.1. From the binding curves (Supporting Information Fig. S1), we were able to determine IC50 values, which were defined as the concentration of solution‐phase GST‐UIM fusion protein that inhibited 50% of the UbV.v27.1‐phage binding to immobilized yUIM‐1 [Fig. 1(B)]. In this assay, UbV.v27.1 exhibited high affinity for yUIM‐1 (IC50 = 0.28 µM), moderate affinity for the third UIM of UFO1 (yUIM‐5, IC50 = 21 µM) and no detectable binding to the other 10 yeast UIMs. Thus, UbV.v27.1 exhibited high affinity and specificity for yUIM‐1 relative to the set of 12 yeast UIMs.

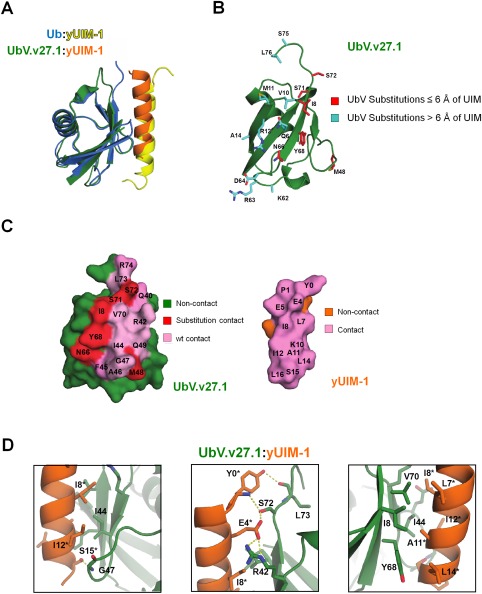

Structure of UbV.v27.1 in complex with yUIM‐1

To understand the molecular basis for how UbV.v27.1 binds to yUIM‐1 with greatly enhanced affinity and specificity, we determined the crystal structure of the complex to 2.35 Å resolution (Table 1, Fig. 2). Superposition of the complex structure with the NMR structure of the interaction of Ub.wt with yUIM‐124 showed that UbV.v27.1 bound to yUIM‐1 in the same orientation as did Ub.wt [Fig. 2(A), RMSD = 0.94 Å]. Notably, of the total 18 substitutions in UbV.v27.1 relative to Ub.wt, only six (Ile8, Met48, Asn66, Tyr68, Ser71, Ser72) were in close proximity to yUIM‐1 [within 6 Å, Fig. 2(B)], and the side‐chains of Met48 and Ser71 pointed away from yUIM‐1. The binding interface involved 497 Å2 and 496 Å2 of buried surface area on UbV.v27.1 and yUIM‐1, respectively [Fig. 2(C)], and was comprised of a mixture of hydrophobic and hydrophilic contacts. This was similar to but somewhat smaller than the binding interface of the native interaction, which involved 558 Å2 and 552 Å2 of buried surface area on Ub.wt and yUIM‐1, respectively.24 Hydrophobic interactions were mediated by contacts between UbV.v27.1 residues Ile8, Ile44, Ala46, Tyr68, and Val70 and yUIM‐1 residues Leu7*, Ile8*, Ala11*, Ile12*, and Leu14* [Fig. 2(D), UIM residues are denoted by asterisks throughout]. Hydrophilic interactions included a hydrogen bond between the side‐chains of Glu4* and Ser72, hydrogen bonds between the side‐chain of Tyr0* (a residue that is not present in the native yUIM‐1 but was added to facilitate assays described in the Methods) and the backbone amide of Leu73 and side‐chain of Ser72, a hydrogen bond between the side‐chain of Ser15* and the backbone amide of Gly47, and lastly, a salt bridge between Glu4* and Arg42 [Fig. 2(D)].

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics of the UbV.v27.1‐yUIM‐1 Complex

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P43212 | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 | |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a,b,c (Å) | 44.61, 44.61, 104.34 | |

|

α, β, γ

|

90, 90, 90 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50‐2.35 | |

| Rmerge | 0.059 (0.302) | |

| CC (1/2) | (0.96) | |

| Total no. of observations | 43385 | |

| Total no. unique observations | 4788 (424) | |

| Mean [(I)/ (I)] | 31.5 (3.41) | |

| Completeness (%) | 98.3 (90.6) | |

| Multiplicity | 9.1 (4.1) | |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 41.02‐2.35 | |

| No. of reflections | 4521 | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.22/0.25 | |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 711 | |

| Ligand/ion | 0 | |

| Water | 8 | |

| Average B‐factors | ||

| Protein | 63.8 | |

| Ligand/ion | N/A | |

| Water | 55.65 | |

| R.m.s.d. | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.0135 | |

| Bond angles | 1.82 | |

| Ramachandran statistics | ||

| Residues in favoured regions (%) | 100 | |

| Residues in allowed regions (%) | 0 | |

| Residues in disallowed regions (%) | 0 | |

Statistics in brackets are for highest resolution shell.

Figure 2.

The crystal structure of the UbV.v27.1‐yUIM‐1 complex. (A) Superposition of the crystal structure of UbV.v27.1 bound to yUIM‐1 with the NMR structure of Ub.wt bound to yUIM‐1 (PDB entry: 1Q0W). (B) Substitutions in UbV.v27.1 relative to Ub.wt. The UbV.v27.1 backbone is shown as a green ribbon with side‐chains of substitutions colored red or cyan for residues ≤6 Å or >6 Å from yUIM‐1, respectively. Of note, the entirety of the side chains for Lys62 and Ser75 could not be modeled. (C) Contact surfaces at the interface between UbV.v27.1 and yUIM‐1. The complex is shown in an open book view with wt and substituted contact residues colored pink or red, respectively, and non‐contact residues on UbV.v27.1 and yUIM‐1 colored green or orange, respectively. (D) Details of the molecular interactions between UbV.v27.1 and yUIM‐1. Polar contacts are shown between Ser15* and Gly47 (left panel), between Tyr0* and Ser72 and Leu73, and between Glu4* and Arg42 and Ser72 (middle panel). Hydrophobic interactions are shown between Ile44 and Ile8* and Ile12* (left panel) and between Leu7*, Ile8*, Ala11*, Ile12* and Leu14*, and Ile8, Ile44, Tyr68 and Val70 (right panel). Asterisks indicate yUIM‐1 residues. An interactive view is available in the electronic version of the article.

Site‐directed mutagenesis of UbV.v27.1 and Ub.wt

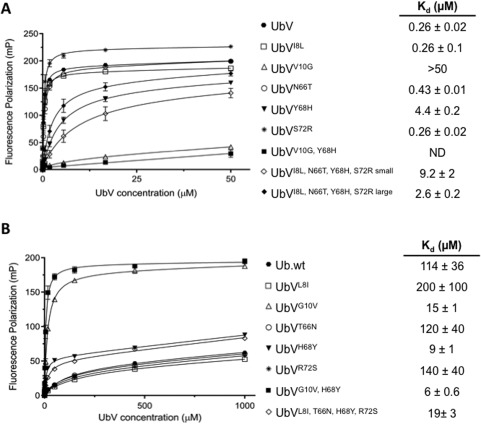

To further dissect the basis for the improved affinity of UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1, we subjected the UbV to site‐directed mutagenesis and measured affinities for yUIM‐1 by a fluorescence polarization assay. In this assay, Ub.wt bound with a K d of 114 µM, which was in reasonable agreement with a published value (277 µM),24 and UbV.v27.1 bound with a K d of 0.26 µM, which was in good agreement with the IC50 value determined by competitive phage ELISA [0.28 µM, Fig. 1(B)]. Only four of the 18 substitutions in UbV.v27.1 (Ile8, Asn66, Tyr68, Ser72) were in close proximity with their side‐chains directed towards yUIM‐1 [Fig. 2(B)], but surprisingly, individual back mutation of each of these four residues in UbV.v27.1 to the wt sequence revealed that only the Tyr68His substitution reduced affinity appreciably [∼17‐fold, Fig. 3(A)]. To assess whether these four residues exhibit cooperativity, we generated a quadruple mutant in which the four positions in UbV.v27.1 were simultaneously reverted to the wt sequence (Ile8Leu, Asn66Thr, Tyr68His, Arg72Ser). During the purification of the quadruple UbV.v27.1 mutant, we noted two distinct peaks from a size exclusion chromatography column (data not shown). Therefore, we purified each peak individually and tested each species for binding to yUIM‐1. The first and second peaks, which corresponded to larger or smaller effective molecular weights, respectively, displayed decreases in affinity of 10‐fold or ∼35‐fold, respectively, which were similar to the decrease observed for the single substitution Tyr68His mutant. Thus, amongst the four contact residues that were substituted in UbV.v27.1 relative to Ub.wt, we concluded that only Tyr68 contributed significantly to enhanced affinity.

Figure 3.

Effects of substitutions on UbV.v27.1 and Ub.wt binding to yUIM‐1. Fluorescence polarization binding experiments are shown for the binding of yUIM‐1 to UbVs harboring the indicated substitutions in the background of (A) UbV.v27.1 or (B) Ub.wt. Fluorescence polarization (y‐axis) was measured for varying concentrations of UbVs (x‐axis) and 25 nM yUIM‐1 peptide (mean of triplicate ±1 SD). For the quadruple substitution in the UbV.v27.1 background, “large” and “small” indicate measurements for the first or second peak that eluted from a SEC column, respectively. ND indicates no detectable binding.

Since the Gly10Val substitution remote from the contact surface of UbV.v27.1 with yUIM‐1 was common to all 7 UbVs selected in our phage display experiment [Fig. 1(A)], we reasoned that it might also contribute to the enhanced binding affinity of UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1. Indeed, the back mutation Val10Gly in UbV.v27.1 caused almost a complete loss of binding affinity for yUIM‐1 (more so than the Tyr68His substitution). Furthermore, introduction of both Val10Gly and Tyr68His resulted in a UbV with almost no binding affinity for yUIM‐1 at the concentration range tested. Thus, we concluded that the Gly10Val and His68Tyr substitutions were both key mediators of the enhanced binding affinity of UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1.

We also examined whether individual introduction of any of the substitutions from UbV.v27.1 into Ub.wt was sufficient to enhance the affinity for yUIM‐1 [Fig. 3(B)]. Consistent with the back mutation data described above, only one of the contact surface substitutions, namely His68Tyr, enhanced the binding affinity (∼13‐fold increase). Furthermore, simultaneous introduction of all four contact substitutions from UbV.v27.1 into Ub.wt resulted in a weaker enhanced affinity (only sixfold) relative to the His68Tyr substitution alone. Taken together, these data confirm that of the four substitutions in UbV.v27.1 on the contact surface with yUIM‐1, only Tyr68 contributes significantly to enhanced affinity for yUIM‐1. We next tested the effect of the Gly10Val substitution in the Ub.wt background. Similar to the effect of the His68Tyr single substitution, the Gly10Val substitution enhanced binding affinity approximately 8‐fold. Moreover, introduction of both Gly10Val and His68Tyr caused a greater enhancement of binding (19 fold), but the resultant affinity (K d = 6 μM) was still significantly lower than the affinity of UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1.

Discussion

The large and diverse array of cellular processes regulated by the Ub system make ubiquitination an attractive process for therapeutic intervention. Design and implementation of phage‐displayed libraries to identify UbVs that bind with enhanced affinity to specific targets has been a boon to such research. Recent applications of this approach have been successful in producing UbVs capable of modulating particular biological functions either as inhibitors or activators of Ub enzymes.31, 32, 33, 34 Here, we have extended this body of work by applying the UbV technology to the UIM subfamily of UBDs.

UbV.v27.1 proved to bind tightly and specifically to yUIM‐1 from yeast Vps27. UbV.v27.1 bound almost 500‐fold more tightly to yUIM‐1 than did Ub.wt (Fig. 3), and binding was highly specific, as only one of the other 11 UIMs in the yeast proteome was recognized, and even its binding was ∼100‐fold weaker [Fig. 1(B)]. The structure of UbV.v27.1 in complex with yUIM‐1 revealed that the UbV binds in the same manner as Ub.wt, and only four of the 18 substitutions relative to Ub.wt have side‐chains that are in close proximity to and point towards the UIM (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, mutagenesis studies of these four substitutions revealed that only the His68Tyr substitution contributed significantly to enhanced binding (Fig. 3). Further investigation revealed that the Gly10Val substitution remote from the contact surface also contributed to the improved binding affinity for yUIM‐1. However, introduction of both substitutions (Gly10Val and His68Tyr) into Ub.wt was not sufficient to impart the full enhancement of affinity displayed by UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1. These results suggest possible contributions from other substitutions remote from the contact surface to the enhanced binding affinity.

While it is easy to rationalize how the His68Tyr substitution contributes to enhanced binding affinity of UbV.v27.1 for yUIM‐1, it is less clear how the Gly10Val substitution exerts its influence. The Gly10Val substitution occurs in a tight turn between strands β1 and β2 of Ub.wt [Fig. 2(B)]. Comparison of this turn between UbV.v27.1 and Ub.wt reveals no obvious structural changes that propagate to the contact surface with yUIM‐1, ruling out a simple allosteric mechanism. However, we note that the Thr9 residue in the middle of the turn could not be unambiguously modeled. This observation may be indicative of an effect on the conformational dynamics of the UbV, as has been observed in the case of UbVs binding to USP14.35 Overall, the influence of a non‐contact residue on affinity emphasizes the complexity and limitations of rational design based on purely structure‐based approaches, which further highlights the power of phage display technology to test billions of unique combinations in an unbiased manner.

In this study, we subjected Ub to variation to find a highly specific and potent binder for yUIM‐1. As there are a large number of UIMs with varying sequences and only a single conserved Ub, it would be interesting to perform the reverse experiment of subjecting a UIM to variation to find a high affinity binder to Ub. Understanding which residues of a UIM can be mutated to enhance affinity for Ub may give additional and complementary insight into the molecular basis for UIM‐Ub interactions.

UbVs engineered for binding to several Ub enzymes have been shown previously to recognize their targets in vivo.31, 32, 33 Importantly, these UbVs also affected the activity of these enzymes and consequently influenced cellular pathways in which the enzymes were involved. Mutation of yUIM‐1 in Vps27 has been shown to cause defective sorting in multivesicular bodies,18 and it may be interesting to determine if UbV.v27.1 can disrupt Vps27‐dependent signaling in yeast cells. Even more intriguingly, the UbV strategy could be extended to targeting the 60 UIMs in the human proteome to reveal new biological functions and potential avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Selection and characterization of UbV‐phage binding to yUIM‐1

A peptide containing the first UIM of Vps27 (GGGGAADEEELIRKAIELSLKESRNSGGY) was biotinylated with N‐hydroxysuccinimidyl d‐biotin‐15‐amido‐4, 7, 10, 13‐tetraoxapentadecylate (NHS‐PEO4‐Biotin) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The biotinylated peptide was immobilized in 96‐well Nunc‐Immuno MAXISORP plates (Thermo Scientific) coated with streptavidin (New England Biolabs), and phage pools representing UbV library 231 were cycled through five rounds of binding selections with the immobilized peptide, as described.36, 37 UbV‐phage clones that bound to the peptide but not to streptavidin or BSA were identified by clonal phage ELISAs and were subjected to DNA sequence analysis to decode the sequences of the displayed UbVs, as described.31

Expression and purification of GST‐UIM fusion proteins

A comprehensive list of 12 yeast UIM domains was curated through annotated domain sites found in the SMART and Uniprot databases.13, 14 Mutagenic oligonucleotides (Supporting Information Table S1) were designed to insert DNA encoding for each UIM in to the pHH0103(TEV) vector (a gift from Cheryl Arrowsmith, Addgene plasmid # 64660) by site‐directed mutagenesis using standard methods36, 38, 39 to create open reading frames encoding for the UIM fused to the carboxy terminus of 6xHis‐GST.

Plasmids designed to express the GST‐UIM fusion proteins were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and single colonies were used to inoculate 5 ml selective 2YT media and cultures were grown overnight with shaking at 37°C. The cultures were used to inoculate 1 L selective 2YT media and were grown with shaking at 37°C to mid‐log phase (OD600 ∼0.8). Protein expression was induced by the addition of 100 µM IPTG (Bio Basic), the temperature was lowered to 18°C, and cultures were incubated overnight with shaking. Bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in 20 ml Lysis Buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mg/ml Lysozyme (BioShop Canada), 0.5% Triton‐X 100, 20 U/ml Benzonase (EMD Millipore), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma‐Aldrich)). Cells were lysed by sonication, and protein purification was performed by incubating cell lysates with 1 ml slurry Ni‐NTA resin (Qiagen) and eluting proteins with an imidazole buffer gradient ranging from 30 to 300 mM. The purity of eluted fractions were confirmed by SDS‐PAGE, and protein concentrations were determined from OD280 measurements with extinction coefficient from ExPASy ProtParam.40

Expression and purification of UbV proteins

For crystallography, the gene encoding for UbV.v27.1 was cloned into the expression vector pHH0239 (a gift from Cheryl Arrowsmith, Addgene plasmid # 51323) to produce an open reading frame encoding for UbV.v27.1 with an N‐terminal 6xHis‐tag and an intervening cleavage site for the Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease, as well as a C‐terminal GAAA motif. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3), a single colony was used to inoculate 5 ml selective 2YT media, and the culture was grown overnight with shaking at 37°C. The culture was used to inoculate 1 L selective 2YT media, and 6xHis‐UbV.v27.1 protein was expressed and purified as described above for GST‐UIM fusion proteins. Purified 6xHis‐UbV.v27.1 was dialyzed into TEV Cleavage Buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM 1,4‐Dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM EDTA) and digested overnight with TEV protease at a 1:100 molar ratio of protease:substrate to remove the 6xHis‐tag as described.33 UbV.v27.1 protein was purified by applying the reaction mixture to Ni‐NTA resin and collecting the unretained fractions. Protein purity was assessed by SDS‐PAGE, and UbV.v27.1 protein was concentrated and buffer‐exchanged into FPLC Buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT) using Amicon Ultra‐4 concentrators with a 3 kDa cutoff (EMD Millipore). The protein was further purified by gel filtration using the ÄKTA system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Hi‐Load 16/60 Superdex 75 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Protein purity was verified by SDS‐PAGE, and UbV.v27.1 protein was concentrated as described above. Final assessment of purity was performed by SDS‐PAGE, and protein concentration was determined from OD280 measurement with extinction coefficient from ExPASy ProtParam.40

For fluorescence polarization experiments, UbV.v27.1 was cloned into pHH0239 and Ub.wt was cloned into pProEX‐HTA (Life Technology) for expression as TEV cleavable N‐terminally 6xHis‐tagged fusions proteins. Both proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) as previously described. Cells were resuspended in Lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 5mM β‐mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol) and lysed by sonication. Cell lysate was loaded onto a 1‐ml HiTrap Chelating HP column (GE Healthcare) and eluted by an imidazole buffer gradient ranging from 5 to 300 mM. Fractions containing UbV.v27.1 or Ub.wt were pooled, dialyzed in Dialysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β‐mercaptoethanol) to remove imidazole, and incubated overnight with TEV protease to cleave the 6xHis tag. After overnight incubation, TEV protease and uncleaved UbV.v27.1 or Ub.wt were removed by applying the reaction mixtures to a 1‐ml HiTrap Chelating HP column (GE Healthcare). UbV.v27.1 or Ub.wt in the flow through fractions was concentrated with a 3 kDa cutoff Amicon Ultra‐4 concentrator (EMD Millipore) and resolved by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex 75 16/600 column (GE Healthcare) previously equilibrated with 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. Peaks corresponding to UbV.v27.1 or Ub.wt were pooled together, concentrated and flash frozen to −80°C. Mutants of UbV.v27.1 and Ub.wt were purified in the same manner. The quadruple UbV.v27.1 mutant eluted as a double peak during SEC. In this case, each peak was collected, concentrated, flash frozen and assayed for binding to yUIM‐1 separately.

Crystallization, structure determination, refinement and analysis

A peptide corresponding to residues 256‐278 of the Vps27 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with a non‐native N‐terminal Tyr residue to aid concentration determination by A280 measurement (YPEDEEELIRKAIELSLKESRNSA, Genscript), was suspended in sterile water for irrigation (Braun Medical, Inc). The peptide solution was mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio with a UbV.v27.1 protein solution to a final concentration of 500 µM. One microliter UbV.v27.1/peptide solution was mixed with 1 μl mother liquor containing 2.1 M DL‐Malic acid pH 7.0, and incubated as hanging drops over lower wells containing 350 μl mother liquor. Crystals were harvested after 17 days, placed in mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol (vol/vol), and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

A single crystal dataset was collected at −180°C on a home‐source consisting of a Rigaku MicroMax‐007 HF rotating anode generator coupled to a Rigaku Saturn 944 HG CCD detector, and was processed using HKL2000.41 The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER42 and a search model of one molecule of yUIM‐1 (PDB ID 1Q0W) and one molecule of Ub with the 5 C‐terminal residues removed (PDB ID 1UBQ). The structure was refined by REFMAC43 and PHENIX,44 both using TLS parameters,45 and manual building in COOT.46 Interactions between yUIM‐1 and UbV.v27.1 were analyzed using the protein interfaces, surfaces and assemblies (PISA) tool.47, 48 Side chain and backbone atoms for residues Gly−6 – Ala0,Thr9, and Arg77 – Ala82 of UbV.v27.1 and Lys17* – Ala23* of yUIM‐1 could not be modeled. Side chain atoms other than the Cβ atoms for Gln2, Glu16, Glu18, Lys29, Ser57, Lys62, Arg74, and Ser75 of Ubv.v27.1 and Glu2* of yUIM‐1 could not be modeled.

Competitive phage ELISAs

Competitive phage ELISAs were performed as described.33 Briefly, GST‐yUIM‐1 fusion protein was immobilized in a 384‐well Nunc MAXISORP plate (Thermo Scientific) and the plate was blocked with BSA. A sub‐saturating concentration of UbV.v27.1‐phage was incubated for 1 h at 25°C with serial dilutions of GST‐UIM fusion protein and the mixtures were transferred to the plate containing immobilized GST‐yUIM‐1. After 15 min of incubation, the plates were washed and bound phages were labeled with α‐M13 antibody/HRP conjugate (1:5,000 dilution, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) for 30 min. The plate was washed and developed with 3,3′,5,5′‐Tetramethylbenzidine Peroxidase Substrate solution (SeraCare), and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a PowerWave XS plate reader (BioTek). Data were plotted with the Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc) and curves were fitted using a one‐site binding Hill model. IC50 values were determined as the concentration of solution‐phase GST‐UIM protein that reduced 50% binding of UbV.v27.1‐phage to immobilized GST‐yUIM‐1.

Fluorescence polarization binding experiments

A peptide corresponding to residues 256‐278 of Vps27 (YPEDEEELIRKAIELSLKESRNSAK, Bio Basic Inc.) was suspended in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl. Subsequently, pH was adjusted to 6.5 by adding 1 M NaOH and 14.8 M ammonium hydroxide to approximate final concentrations of 5 mM and 30 mM, respectively. The peptide contained a non‐native N‐terminal tyrosine to aid concentration determination and a non‐native C‐terminal lysine to allow covalent labeling with 5/6‐carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (NHS‐FITC) (Bio Basic Inc.). The C‐terminus was amidated and the N‐terminus was acetylated to prevent charge effects from the termini affecting peptide binding. Peptide concentration was determined from absorbance measurement at 495 nm using the extinction coefficient of FITC (75,000 L mol−1 cm−1). Binding measurements were performed in FP buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01 mg/ml BSA, 0.03% BRIJ‐35) by mixing in a 96‐well plate 25 nM FITC‐labeled yUIM‐1 peptide with serial dilutions of Ub.wt and its variants ranging from 1 mM to 22 nM. For UbV.v27.1 and its variants, binding measurements were performed similarly with concentrations varying from 50 µM to 0.28 nM. Samples were equilibrated at room temperature for 30 min before reading plates on a HTS Multi‐Mode Microplate Reader (Synergy Neo) using an excitation filter of 485 nm and an emission filter of 530 nm. Dissociation constants were determined with Prism (GraphPad Software Inc) using a one‐site total binding model. For the quadruple mutant of UbV.v27.1, which eluted as two distinct peaks by SEC, binding measurements were made on both species.

Accession Number

Coordinate and structure factors for the UbV.v27.1‐yUIM‐1 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 5UCL.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. GI Makhatadze for providing peptides and for helpful discussions.

Statement: Ubiquitin regulates many biological events by interacting weakly but specifically with ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs). Here we describe the generation of a ubiquitin variant (UbV) with unprecedented affinity and specificity for UIMs. Structural analysis revealed the basis for such an improved interaction, enabling the identification of the molecular determinants for binding. UbVs provide a tool to investigate the interaction of ubiquitin with its binding partners and could be harnessed for therapeutic intervention.

Contributor Information

Frank Sicheri, Email: sicheri@lunenfeld.ca.

Sachdev S. Sidhu, Email: sachdev.sidhu@utoronto.ca

References

- 1. Pickart CM (2001) Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem 70:503–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spence J, Sadis S, Haas AL, Finley D (1995) A ubiquitin mutant with specific defects in DNA repair and multiubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol 15:1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang TT, D'Andrea AD (2006) Regulation of DNA repair by ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glotzer M, Murray AW, Kirschner MW (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 349:132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakayama KI, Nakayama K (2006) Ubiquitin ligases: cell‐cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6:369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hershko A, Ciechanover A (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67:425–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dikic I, Dötsch V (2009) Ubiquitin linkages make a difference. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16:1209–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Komander D (2009) The emerging complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem Soc Trans 37:937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hurley JH, Lee S, Prag G (2006) Ubiquitin‐binding domains. Biochem J 399:361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP (2005) Ubiquitin‐binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:610–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ (2009) Ubiquitin‐binding domains ‐ from structures to functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen ZJ, Sun LJ (2009) Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell 33:275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ponting CP, Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P (1999) SMART: identification and annotation of domains from signalling and extracellular protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27:229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anon (2015) UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D204–D212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hofmann K, Falquet L (2001) A ubiquitin‐interacting motif conserved in components of the proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation systems. Trends Biochem Sci 26:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gucwa AL, Brown DA (2014) UIM domain‐dependent recruitment of the endocytic adaptor protein Eps15 to ubiquitin‐enriched endosomes. BMC Cell Biol 15:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piper RC, Luzio JP (2007) Ubiquitin‐dependent sorting of integral membrane proteins for degradation in lysosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19:459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katzmann DJ, Stefan CJ, Babst M, Emr SD (2003) Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J Cell Biol 162:413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yan J, Kim Y‐S, Yang X‐P, Li L‐P, Liao G, Xia F, Jetten AM (2007) The ubiquitin‐interacting motif containing protein RAP80 interacts with BRCA1 and functions in DNA damage repair response. Cancer Res 67:6647–6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu X, Paul A, Wang B (2012) Rap80 protein recruitment to DNA double‐strand breaks requires binding to both small ubiquitin‐like modifier (SUMO) and ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem 287:25510–25519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qin W, Wolf P, Liu N, Link S, Smets M, La Mastra F, Forné I, Pichler G, Hörl D, Fellinger K, Spada F, Bonapace IM, Imhof A, Harz H, Leonhardt H (2015) DNA methylation requires a DNMT1 ubiquitin interacting motif (UIM) and histone ubiquitination. Cell Res 25:911–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polo S, Sigismund S, Faretta M, Guidi M, Capua MR, Bossi G, Chen H, De Camilli P, Di Fiore PP (2002) A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature 416:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller SLH, Malotky E, O'Bryan JP (2004) Analysis of the role of ubiquitin‐interacting motifs in ubiquitin binding and ubiquitylation. J Biol Chem 279:33528–33537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swanson KA, Kang RS, Stamenova SD, Hicke L, Radhakrishnan I (2003) Solution structure of Vps27 UIM‐ubiquitin complex important for endosomal sorting and receptor downregulation. EMBO J 22:4597–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Q, Young P, Walters KJ (2005) Structure of S5a bound to monoubiquitin provides a model for polyubiquitin recognition. J Mol Biol 348:727–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirano S, Kawasaki M, Ura H, Kato R, Raiborg C, Stenmark H, Wakatsuki S (2006) Double‐sided ubiquitin binding of Hrs‐UIM in endosomal protein sorting. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13:272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Husnjak K, Dikic I (2012) Ubiquitin‐binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin‐mediated cellular functions. Annu Rev Biochem 81:291–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim HC, Steffen AM, Oldham ML, Chen J, Huibregtse JM (2011) Structure and function of a HECT domain ubiquitin‐binding site. EMBO Rep 12:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbé S (2009) Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lechtenberg BC, Rajput A, Sanishvili R, Dobaczewska MK, Ware CF, Mace PD, Riedl SJ (2016) Structure of a HOIP/E2∼ubiquitin complex reveals RBR E3 ligase mechanism and regulation. Nature 529:546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ernst A, Avvakumov G, Tong J, Fan Y, Zhao Y, Alberts P, Persaud A, Walker JR, Neculai A‐M, Neculai D, Vorobyov A, Garg P, Beatty L, Chan P‐K, Juang Y‐C, Landry M‐C, Yeh C, Zeqiraj E, Karamboulas K, Allali‐Hassani A, Vedadi M, Tyers M, Moffat J, Sicheri F, Pelletier L, Durocher D, Raught B, Rotin D, Yang J, Moran MF, Dhe‐Paganon S, Sidhu SS (2013) A strategy for modulation of enzymes in the ubiquitin system. Science 339:590–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang W, Wu K‐P, Sartori MA, Kamadurai HB, Ordureau A, Jiang C, Mercredi PY, Murchie R, Hu J, Persaud A, Mukherjee M, Li N, Doye A, Walker JR, Sheng Y, Hao Z, Li Y, Brown KR, Lemichez E, Chen J, Tong Y, Harper JW, Moffat J, Rotin D, Schulman BA, Sidhu SS (2016) System‐wide modulation of HECT E3 ligases with selective ubiquitin variant probes. Mol Cell 62:121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gorelik M, Orlicky S, Sartori MA, Tang X, Marcon E, Kurinov I, Greenblatt JF, Tyers M, Moffat J, Sicheri F, Sidhu SS (2016) Inhibition of SCF ubiquitin ligases by engineered ubiquitin variants that target the Cul1 binding site on the Skp1‐F‐box interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:3527–3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang W, Sidhu SS (2014) Development of inhibitors in the ubiquitination cascade. FEBS Lett 588:356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Phillips AH, Zhang Y, Cunningham CN, Zhou L, Forrest WF, Liu PS, Steffek M, Lee J, Tam C, Helgason E, Murray JM, Kirkpatrick DS, Fairbrother WJ, Corn JE (2013) Conformational dynamics control ubiquitin‐deubiquitinase interactions and influence in vivo signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:11379–11384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fellouse FA, Esaki K, Birtalan S, Raptis D, Cancasci VJ, Koide A, Jhurani P, Vasser M, Wiesmann C, Kossiakoff AA, Koide S, Sidhu SS (2007) High‐throughput generation of synthetic antibodies from highly functional minimalist phage‐displayed libraries. J Mol Biol 373:924–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tonikian R, Zhang Y, Boone C, Sidhu SS (2007) Identifying specificity profiles for peptide recognition modules from phage‐displayed peptide libraries. Nat Protoc 2:1368–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kunkel TA (1985) Rapid and efficient site‐specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:488–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sidhu SS, Lowman HB, Cunningham BC, Wells JA (2000) Phage display for selection of novel binding peptides. Methods Enzymol 328:333–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, Hochstrasser DF (1999) Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol 112:531–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X‐ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCoy AJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst 40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum‐likelihood method. Acta Cryst D53:240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L‐W, Kapral GJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python‐based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst D66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Painter J, Merritt EA (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Cryst D62:439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model‐building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst D60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krissinel E, Henrick K (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372:774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krissinel E (2010) Crystal contacts as nature's docking solutions. J Comput Chem 31:133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information