Abstract

Objectives:

Microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE) is an optimal technique of sperm extraction for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. This study is to present our experience in micro-TESE and evaluate the relation of its sperm retrieval rate (SRR) with patients' characteristics, testicular functions, and histological parameters as well as previous sperm retrieval interventions.

Materials and Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed records of 255 patients with nonobstructive azoospermia who underwent micro-TESE between 2011 and 2014. Medical records were reviewed for the results of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), total testosterone levels, karyotype analysis, and testicular histology pattern. Testicular volume was measured with an ultrasound scale.

Results:

The mean patients' age was 35.8 ± 7.2 years, duration of infertility 7.7 ± 4.5 years, right testicular volume 13.1 ± 5 ml, and left testicular volume 12.9 ± 5 ml. The overall SRR was 43.9%. SRR was significantly higher in testes with hypospermatogenesis histology pattern (P = 0.011). Patients' age, testicular size, serum FSH, LH, prolactin, and testosterone or failed previous sperm retrieval interventions showed no significant impact on SRR. Eleven (4.3%) patients had nonmosaic Klinefelter syndrome with a mean age of 37.8 ± 3.3 years. Sperms were retrieved in 6 (54.5%) patients. Post micro-TESE androgens significantly deteriorated with near complete recovery after 1 year.

Conclusions:

Micro-TESE has a high SRR, minimal postoperative complications, and reversible long-term androgen deficiency. Sperm retrieval depends on the most advanced pattern of testicular histology. Hypospermatogenesis pattern has the highest SRR. We demonstrated a high SRR with micro-ESE in men with Klinefelter syndrome.

Key Words: Microdissection testicular sperm extraction, nonobstructive azoospermia, Saudi Arabia, sperm retrieval

INTRODUCTION

Azoospermia is defined as the absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate after the assessment of centrifuged semen on at least two occasions. It is observed in 1% of the general population and in 10%–15% of infertile men.[1,2]

Surgical sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) have revolutionized the management of nonobstructive azoospermia (NOA).[3,4,5] Fine-needle aspiration (FNA), percutaneous testis biopsy, and open testicular biopsy or testicular sperm extraction (TESE) can be used to retrieve testicular spermatozoa.[6,7] Failure to extract spermatozoa may occur in up to 57% of TESE attempts.[5,6,7,8] Focal testicular spermatogenesis accounts for the failure rate of these procedures.[9] Furthermore, multiple testicular biopsies can result in the loss of testicular tissue and can interrupt the testicular blood supply underneath the tunica albuginea with risks of testicular devascularization and atrophy of the testis.[10] Microdissection TESE (micro-TESE) was introduced to try to sample focal healthy looking tubules, thus to maximize the yield of spermatozoa, reduce the amount of testicular tissue removed, improve sperm retrieval rate (SRR), and avoid subtunical vessels.[11,12,13,14]

We evaluated our experience in micro-TESE trying to detect the relation of micro-TESE SRR with patients' characteristics, testicular functions, and histological parameters as well as previous sperm retrieval interventions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

We retrospectively evaluated 255 patients with nonobstructive azoospermia with healthy female partners who had undergone micro-TESE between 2011and 2014 in our institution.

All patients were diagnosed on the basis of a complete history, physical examination, and endocrine profile. Medical records were reviewed for the results of preoperative testicular biopsy, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), total testosterone levels, karyotype analysis, and previous interventions for sperm extraction.

Testicular volume was measured with an ultrasound scale. Each testis was further categorized into small (<15 ml) or average sized (15 ml or greater). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board.

Seminal study

Semen samples were produced by masturbation after 3–5 days of sexual abstinence and collected into sterile containers. The presence of azoospermia was documented in at least two semen specimens more than 2 weeks apart, all processed with centrifugation at 3000 g and extensive examination of the resuspended pellet. A repeat analysis was also performed on the morning of the planned sperm retrieval.

Hormonal measurements

Serum FSH, LH, total testosterone, prolactin, and estradiol were measured and recorded preoperatively, at 3 months (early) and more than 1 year (late) follow up visits.

Microdissection testicular sperm extraction

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Procedures were performed under general or regional anesthesia and in one patient under local anesthesia, with the patient positioned on an operating table in a supine position. A floor-standing operating microscope (OPMI Vario/S88 System, Karl Zeiss, Germany) was used throughout the procedures. After skin disinfecting and draping, the scrotal skin was stretched over the anterior surface of the testis, and a 2.5-cm midline raphe longitudinal incision was placed. The incision was carried out through the dartos muscle and tunica vaginalis. The tunica was opened and its bleeders cauterized. The testis was delivered extravaginally and the tunica albuginea was examined. A single large longitudinal intra-polar incision was made on an avascular area in the tunica albuginea under ×6–8 magnification, and the testicular parenchyma was widely exposed. A small testicular fragment is excised from the medium testicular pole and placed in Bouin's fixative for histopathology examination. Dissection of the testicular parenchyma was then undertaken at ×16–25 magnification searching for enlarged tubules, which are more likely to contain germ cells. The superficial and deep testicular regions were examined, as needed, and microsurgical-guided testicular biopsies were performed by carefully removing enlarged and opaque tubules using microsurgical forceps. If enlarged tubules were not seen, then two to three random micro-biopsies were performed at the upper, medium, and lower testicular poles. The excised specimens were placed into the center well of Petri dishes containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in room temperature and processed as described below. The tunica albuginea was closed using continuous nonabsorbable 5-0 polydioxanone sutures suture. Following hemostasis, the tunica vaginalis was closed in a running fashion using similar suture, then the dartos muscle was closed with interrupted Vycril sutures. Finally, the skin was closed with continuous subcuticular 5-0 monocryl suture, and a fluffy-type dressing and scrotal supporter were placed. The procedures were carried out at the contralateral testicle, as needed, when an insufficient number or no sperm have been found at initial laboratory examination. Patients were discharged same day of surgery. Success was defined as the presence of a sperm that could be either preserved or used for ICSI. All operative procedures were performed by one surgeon (S.B.) in a single tertiary academic center.

Tissue processing and sperm retrieval

Testicular tissues obtained at the procedure were put directly with PBS into a Petri dish (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, USA), minced and shredded using a couple of disposable sterile needles then examined immediately under an inverted microscope with Hoffman Modulation optics using ×400 magnifications for the presence of spermatozoa. The entire Petri dish was checked and if no spermatozoa were seen, the whole tissue and the buffered medium were replaced in a conical tube, shaken very well then let to settle down for 1 or 2 min. The supernatant was removed into a clean tube and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 50 μl of buffered medium and carefully checked again for the presence of spermatozoa by an experienced embryologist.

Histopathology

When available, testicular histology, based on the most advanced histopathological pattern, was classified into hypospermatogenesis (a reduction in the number of normal spermatogenetic cells), maturation arrest (an absence of the later stages of spermatogenesis), Sertoli cell only (SCO) (the absence of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules), or diffuse tubular atrophy with tubular hyalinization or sclerosis (no germ cell or Sertoli cell present in the tubules).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were presented as the mean (standard deviation) and percent. For comparative statistics Chi-square/Fisher's exact tests, independent t-test, and Wilcoxon signed ranks test were used as appropriate. The value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests performed using the Predictive Analysis Software version 19.1 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 255 patients underwent micro-TESE. The mean age of the patients was 35.8 ± 7.2 years. The mean duration of infertility was 7.7 ± 4.5 years. The mean right testicular volume was 13.1 ± 5 ml and the mean left testicular volume was 12.9 ± 5 ml. Clinically, 268 (52.6%) testes were small sized, 221 (43.3%) average sized, and 21 (4.1%) were unilaterally absent because of orchidectomy for nondescent in childhood or torsion.

Both testes were explored in 187 patients and one was examined in 68 because of absent testis in 21 or retrieval of enough sperms from one side in 47. The sperm retrieval was successful in 112 (43.9%) patients and unsuccessful (no sperm found) in 143 (56.1%) patients. The overall SRR was 43.9%. That was 39.2% (85/217) from the left side and 37.8% (85/225) from the right side. No intraopertative complications were encountered in our patients. Postoperative complications were recorded in 2 (0.8%) patients; one scrotal edema and one surgical site infection. None required surgical intervention.

When the influence of histological diagnosis was considered, SRR was significantly higher in testes with hypospermatogenesis histology pattern than in testes with other histological diagnosis (P = 0.011). Patients' age, testicular size, serum FSH, LH, prolactin, and testosterone or failed previous sperm retrieval interventions showed no significant impact on SRR [Table 1].

Table 1.

Relation of patient, testicular, hormonal, and histological parameters to sperm retrieval rate

Of the patients, 118 (46.3%) had a failed previous sperm retrieval intervention in the form of fine needle testicular sperm aspiration (five patients), conventional TESE (111), or micro-TESE (2). Spermatozoa were successfully retrieved by micro-TESE in 50 (42.4%) of these patients.

The karyotype analysis revealed nonmosaic Klinefelter syndrome in 11 (4.3%) patients with a mean age of 37.8 ± 3.3 years. They had small testes with a mean testicular volume of 6.1 ± 4.5 ml. Their mean serum FSH, LH, and testosterone were 29.8 ± 15.5 IU/L, 20.1 ± 9.7 IU/L, and 7.5 ± 1.6 nmol/L, respectively. The histopathology was available in six patients and showed SCO pattern. Sperms were retrieved in six patients with a SRR of 54.5%.

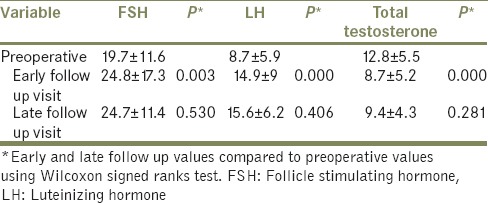

Pre- and post-operative hormonal measurements were available for comparison on 111 patients. A comparison between levels of serum hormones before micro-TESE and at early and late follow-up visits is presented in Table 2. Early follow up results revealed that serum FSH and LH have significantly increased and serum testosterone has significantly decreased than preoperative levels. However, near complete recovery has been observed after 1 year with late follow up hormonal measurements that were not significantly different than the preoperative hormonal values [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pre- and post-operative hormonal measurements

DISCUSSION

The introduction of ICSI, and the application of various testicular sperm retrieval techniques, have revolutionized treatment in patients with NOA.[3,4,5] Various methods can be used to retrieve testicular spermatozoa, including FNA, open testicular biopsy, and percutaneous biopsy.[6,7] The introduction of micro-TESE has improved SRR, maximized the yield of spermatozoa per biopsy, resulted in removal of less testicular tissue and had fewer acute and chronic complications than conventional procedures.[9,11,14]

SRR between 33.3% and 63% have been reported after micro-TESE.[11,15,16] In our series, SRR was 43.9%. Our SRR is similar to what have been reported by Okada et al.,[12] Tsujimura et al.,[13] and Amer et al.[14]

As sperm retrieval depends only on finding sperm in just one small testicular focus, data such as testicular volume, serum FSH, and the presence of associated male pathologies cannot be used as predictive factors of success.[5,13,17,18] Our results concur with previously published studies that showed patients' age, testicular size, serum FSH, and testosterone or failed previous interventions for sperm retrieval had no impact on SRR [Table 1].

Moreover, as sperm retrieval depends on the most advanced pattern of testicular histology.[17] We retrieved spermatozoa in 90% of men with hypospermatogenesis in comparison to 39.2% and 55.6% of men with SCO and maturation arrest histology, respectively. Comparable results were reported in the literature.[12,13,14,18] Others reported higher rates.[9,15,19] Obviously, it is difficult to compare various reports because of the presence of mixed histology patterns, complete or incomplete pattern forms and various stages of spermatogenesis arrest.

Our results showed a significant deterioration of hormone levels during the 1st year with near recovery after that [Table 2]. Everaert et al.[16] previously showed that micro-TESE is associated with a significant long-term decrease of serum testosterone levels. Serum levels of FSH and LH also increased at follow-up. Similarly, Manning et al.[20] found that testosterone levels decreased initially after nonmicrosurgical TESE in most patients with partial recovery after 1 year. This deterioration of hormone levels may be attributed to loss of testicular tissue removed during surgery, surgical trauma, and inflammation as well as vascular injury to the testis.[10,16] Patients need to be counseled on the long-term consequences of TESE, including possible androgen deficiency and its therapy.[21] As some degree of spontaneous recovery may occur, it seems prudent to wait for about 1 year after the surgery before starting replacement therapy.[16,22]

We retrieved spermatozoa in 54.5% of patients with Klinefelter syndrome in spite of small testes, high FSH and LH, low testosterone, and predominant SCO histology. Similar results were reported by Sciurano et al.[23] Better outcomes in men with Klinefelter syndrome have been reported.[23,24,25] Bryson et al.[24] reported a SRR of 81.8% in young men, <30 years, with Klinefelter syndrome and 33.3% in men over the age of 30. Similarly, the SRR was found to decrease significantly after the age of 35 years.[26] None of our Klinefelter group of patients was <30 years with a mean age of 37.8 ± 3.3 years. History of Klinefelter syndrome was a significant predictor of sperm retrieval in a group of 1026 men who underwent microdissection sperm extraction for nonobstructive azoospermia.[27] It is yet unclear why men with Klinefelter syndrome can have isolated areas of intact spermatogenesis. A possible theory is that rare nondisjunction events may select for XY clones in developing germ cells, which are then able to proceed through meiosis to form normal haploid spermatogonia.[21,23]

Being of a retrospective nature, our study is limited by the inherent limitations of retrospective studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Micro-TESE has a high SRR, minimal postoperative complications, and reversible long-term androgen deficiency. Sperm retrieval depends on the most advanced pattern of testicular histology. Hypospermatogenesis has the highest SRR. Patients' age, testicular size, serum FSH, LH, prolactin, and testosterone or failed previous sperm retrieval interventions showed no significant impact on SRR. We demonstrated a high SRR with micro-TESE in men with Klinefelter syndrome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Willott GM. Frequency of azoospermia. Forensic Sci Int. 1982;20:9–10. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(82)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarow JP, Espeland MA, Lipshultz LI. Evaluation of the azoospermic patient. J Urol. 1989;142:62–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silber SJ, Nagy Z, Liu J, Tournaye H, Lissens W, Ferec C, et al. The use of epididymal and testicular spermatozoa for intracytoplasmic sperm injection: The genetic implications for male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2031–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devroey P, Liu J, Nagy Z, Tournaye H, Silber SJ, Van Steirteghem AC. Normal fertilization of human oocytes after testicular sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:639–41. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56958-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devroey P, Liu J, Nagy Z, Goossens A, Tournaye H, Camus M, et al. Pregnancies after testicular sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1457–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.6.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedler S, Raziel A, Strassburger D, Soffer Y, Komarovsky D, Ron-El R. Testicular sperm retrieval by percutaneous fine needle sperm aspiration compared with testicular sperm extraction by open biopsy in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1488–93. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.7.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenlund B, Kvist U, Plüen L, Rozell BL, Sjüblom P, Hillensjü T. A comparison between open and percutaneous needle biopsies in men with azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1266–71. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlegel PN, Palermo GD, Goldstein M, Menendez S, Zaninovic N, Veeck LL, et al. Testicular sperm extraction with intracytoplasmic sperm injection for nonobstructive azoospermia. Urology. 1997;49:435–40. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silber SJ. Microsurgical TESE and the distribution of spermatogenesis in non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2278–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlegel PN, Su LM. Physiological consequences of testicular sperm extraction. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1688–92. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.8.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlegel PN. Testicular sperm extraction: Microdissection improves sperm yield with minimal tissue excision. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:131–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada H, Dobashi M, Yamazaki T, Hara I, Fujisawa M, Arakawa S, et al. Conventional versus microdissection testicular sperm extraction for nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol. 2002;168:1063–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsujimura A, Matsumiya K, Miyagawa Y, Tohda A, Miura H, Nishimura K, et al. Conventional multiple or microdissection testicular sperm extraction: A comparative study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2924–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.11.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amer M, Ateyah A, Hany R, Zohdy W. Prospective comparative study between microsurgical and conventional testicular sperm extraction in non-obstructive azoospermia: Follow-up by serial ultrasound examinations. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:653–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsujimura A, Miyagawa Y, Takao T, Takada S, Koga M, Takeyama M, et al. Salvage microdissection testicular sperm extraction after failed conventional testicular sperm extraction in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol. 2006;175:1446–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everaert K, De Croo I, Kerckhaert W, Dekuyper P, Dhont M, Van der Elst J, et al. Long term effects of micro-surgical testicular sperm extraction on androgen status in patients with non obstructive azoospermia. BMC Urol. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel Raheem A, Garaffa G, Rushwan N, De Luca F, Zacharakis E, Abdel Raheem T, et al. Testicular histopathology as a predictor of a positive sperm retrieval in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. BJU Int. 2013;111:492–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madbouly K, Alaskar A, Al Matrafi H. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of intraoperative findings in microdissection testicular sperm extraction: A prospective study. Curr Urol. 2009;2:130–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernie AM, Ramasamy R, Schlegel PN. Predictive factors of successful microdissection testicular sperm extraction. Basic Clin Androl. 2013;23:5. doi: 10.1186/2051-4190-23-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning M, Jünemann KP, Alken P. Decrease in testosterone blood concentrations after testicular sperm extraction for intracytoplasmic sperm injection in azoospermic men. Lancet. 1998;352:37. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schill T, Bals-Pratsch M, Küpker W, Sandmann J, Johannisson R, Diedrich K. Clinical and endocrine follow-up of patients after testicular sperm extraction. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramasamy R, Schlegel PN. Microdissection testicular sperm extraction: Effect of prior biopsy on success of sperm retrieval. J Urol. 2007;177:1447–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciurano RB, Luna Hisano CV, Rahn MI, Brugo Olmedo S, Rey Valzacchi G, Coco R, et al. Focal spermatogenesis originates in euploid germ cells in classical Klinefelter patients. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2353–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryson CF, Ramasamy R, Sheehan M, Palermo GD, Rosenwaks Z, Schlegel PN. Severe testicular atrophy does not affect the success of microdissection testicular sperm extraction. J Urol. 2014;191:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berookhim BM, Palermo GD, Zaninovic N, Rosenwaks Z, Schlegel PN. Microdissection testicular sperm extraction in men with Sertoli cell-only testicular histology. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1282–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada H, Goda K, Yamamoto Y, Sofikitis N, Miyagawa I, Mio Y, et al. Age as a limiting factor for successful sperm retrieval in patients with nonmosaic Klinefelter's syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1662–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramasamy R, Padilla WO, Osterberg EC, Srivastava A, Reifsnyder JE, Niederberger C, et al. A comparison of models for predicting sperm retrieval before microdissection testicular sperm extraction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol. 2013;189:638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]