Introduction

Voriconazole is a triazole antifungal agent active against a variety of fungi and molds, such as Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Scedosporium and Cryptococcous. It is particularly recommended for pulmonary invasive aspergillosis, an infection that primarily occurs in immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing organ transplantation or with autoimmune conditions [1, 2]. Voriconazole and other triazole antifungals work by disrupting the synthesis of a compound found in fungal cell membranes called ergosterol. Disruption of ergosterol synthesis leads to damage to the fungal cell membrane, and eventual fungal cell death or inhibition of fungal cell growth [3]. While voriconazole is generally well-tolerated and effective, it has a narrow therapeutic window. Drug levels that are too low can diminish efficacy, while those that are too high can affect tolerability and safety [2, 4]. Serious adverse events associated with voriconazole use include hepatotoxicity and central nervous system effects; visual disturbances are also common, particularly at higher concentrations of the drug [5]. The metabolism and clearance of voriconazole, and consequently the levels of the drug within the body, are influenced by CYP2C19 genotype. Non-genetic factors that affect voriconazole levels include patient age, gender, liver disease and concomitant medications [6]. Drug labels for voriconazole approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada note that individuals who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers exhibit, on average, 4-fold higher drug exposure as compared to normal (extensive) metabolizers [7, 8]. However, the evidence that supports a direct association between between CYP2C19 and toxicity or efficacy is limited. This review will provide an overview of the literature on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of voriconazole. A particular emphasis will be given to pharmacogenetics, as developments in this area may provide a way to optimize dosing.

Pharmacokinetics

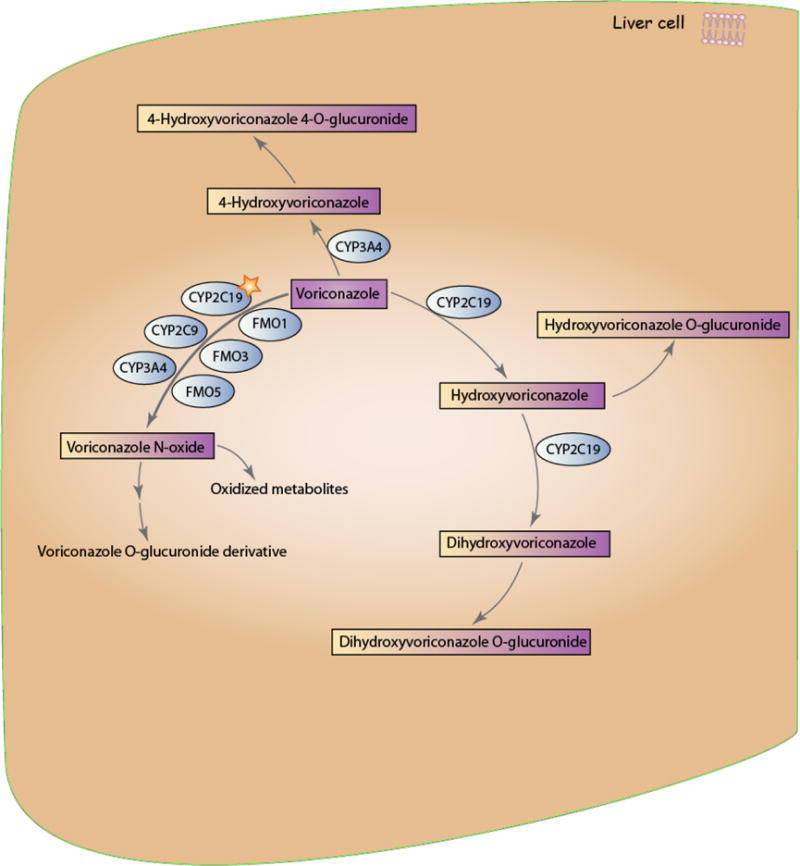

A schematic representation of voriconazole disposition within the body is provided in Figure 1. Voriconazole is extensively metabolized, with less than 2% of the original dose excreted in unchanged form [9]. The main circulating metabolite is voriconazole N-oxide, which has no antifungal activity [9, 10]. CYP2C19 is the primary enzyme responsible for the metabolism of voriconazole into voriconazole N-oxide, though CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and members of the flavin containing monooxygenase (FMO) family also contribute [9–12]; it’s estimated that approximately 75% of the total voriconazole metabolism is mediated through the CYP enzymes, while the FMO family mediates the remaining 25% [11]. Voriconazole N-oxide can also be further metabolized into various less-prevalent metabolites [13]. Voriconazole has the potential to be both a substrate and an inhibitor of the CYP2C19, CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 enzymes [9].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of voriconazole pharmacokinetics. The star indicates that CYP2C19 is the primary enzyme involved in voriconazole metabolism. A fully interactive version is available online at http://www.pharmgkb.org/molecule/PA10233.

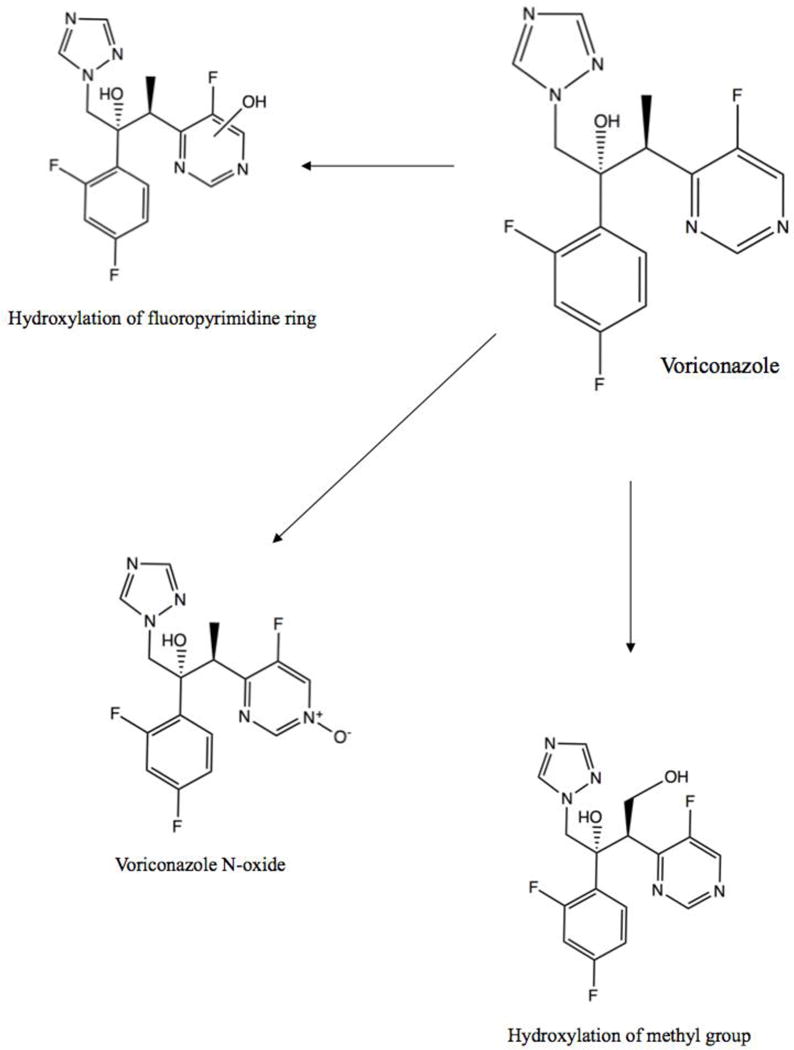

Voriconazole has two other main routes of metabolism: one is the hydroxylation of the methyl group, and the other is hydroxylation of the fluoropyrimidine ring [11, 13]. Figure 2 shows the chemical structures for these two hydroxylated metabolites, as well as the structure for voriconazole N-oxide. Though no information is available regarding the enzymes involved in the hydroxylation of the fluoropyrimidine ring, hydroxylation of the methyl group is believed to occur through the action of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 [11, 12, 14]. After hydroxylation, both metabolites form glucuronidated metabolites. Additionally, the hydroxymethyl metabolite can be hydroxylated again via CYP2C19 to form dihydroxy-voriconazole; this dihydroxy metabolite can then be glucuronidated [13, 14]. Bourcier et al. found that UGT1A4 is the main enzyme involved in the glucuronidation of voriconazole, though no information about its role in glucuronidation of voriconazole metabolites is available [15].

Figure 2. Chemical structures of the main voriconazole metabolites.

The three primary routes of voriconazole metabolism are hydroxylation of the fluoropyrimidine ring, hydroxylation of the methyl group, and N-oxidation [13]. The notation used with regard to the OH group in the “Hydroxylation of the fluoropyrimidine ring” metabolite indicates that the location of the attachment of the OH group is variable – OH is bonded to the ring, but at an unspecified or unknown atom of the ring.

Pharmacogenetics

Studies on the pharmacogenetics of voriconazole have been done in both healthy adult individuals and immunocompromised patients; Table 1 provides an overview of these pharmacogenetic studies. Studies on healthy adults measured differences between CYP2C19 genotypes for a variety of pharmacokinetic parameters, such as clearance, area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC), median residence time (MRT), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), trough concentration, and elimination half-life (T1/2) [14, 16, 17]. For the purposes of this review, we will occasionally group these parameters together and refer to CYP2C19 genotypes as affecting the “metabolism” of voriconazole. Studies in immunocompromised patients focused exclusively on trough or dose-adjusted trough concentrations of voriconazole [18–20]. A major limitation of voriconazole pharmacogenetic studies is small cohort sizes – across studies on poor metabolizers (PMs), intermediate metabolizers (IMs) and ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs), approximately half of all studies had less than 30 individuals, the majority had less than 50, and only two studies included over 100 individuals [21, 22]. One meta-analysis has examined the association between CYP2C19 variants and voriconazole trough concentrations and clinical outcomes: Li et al. found that PMs had increased trough concentrations as compared to normal metabolizers (NMs)1 and IMs across 6 studies, and that IMs had increased trough concentrations as compared to NMs across 7 studies. They also found that PMs had increased treatment success as compared to NMs (across 4 studies); however, no significant association with adverse effects was seen between PMs, IMs, NMs and UMs [23]. Literature evidence for the effect of variants in other genes involved in voriconazole metabolism or concentration, such as CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, is very limited. One recent study found that dosing voriconazole based on CYP2C19 genotype leads to faster achievement of target concentrations, suggesting that preemptive CYP2C19 genotyping may be useful in the clinic [24].

Table 1. Pharmacogenetic studies for CYP2C19 and voriconazole.

All pharmacokinetic findings are written in comparison to results for normal (extensive) metabolizers (NMs; *1/*1) unless otherwise stated. Poor metabolizers (PMs) refer to the CYP2C19 genotypes *2/*2, *2/*3 or *3/*3, and intermediate metabolizers (IMs) to genotypes *1/*2 or *1/*3 unless otherwise stated. UM genotypes are given. For more detailed information about the findings in each of the studies in this table, please visit www.pharmgkb.org/molecule/PA10233.

| CYP2C19 Phenotype | Patient condition | Study size | Ethnicity | Pharmacokinetic findings | Clinical findings | p-value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM | Healthy | 12 | Japanese | Increased AUC, C0 and Cmax | [30] | ||

| Healthy | 20 | White | Increased AUC, t1/2 and MRT; decreased CL | <0.01 | [16] | ||

| Healthy males | 20 | Chinese | Increased AUC and t1/2; decreased CL | ≤0.002 | [17] | ||

| Healthy | 35 | White | Increased AUC and t1/2; decreased CL | <0.01 | [31] | ||

| Healthy males | 14 | Chinese | Increased AUC; decreased CL | <0.05 | [32] | ||

| Healthy | 20 | White | Increased AUC and MRT; decreased CL | <0.05 | [14] | ||

| Healthy males | 18 | Chinese | Increased AUC and t1/2; decreased CL | <0.05 | [33] | ||

| Healthy males | 18 | Korean | Increased AUC, C0 and Cmax | [34] | |||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | White | t1/2 ~3–4X compared to normal volunteers, decreased CL | VCZ discontinuation | [36] | ||

| Presumed pulmonary aspergillosis | 1 | Hispanic | AUC and C0 2–3X higher than target values | QTc prolongation possibly related to elevated VCZ levels; VCZ discontinuation | [37] | ||

| Fungal infection or underlying disease | 92 | Increased C0 | 0.0029 | [20] | |||

| Immunocompromised pediatric patients with invasive fungal infections or VCZ prophylaxis | 33 | Increased C0/D | 0.04 | [18] | |||

| Proven or probable invasive fungal infection | 144 | Increased C0 | <0.05 | [21] | |||

| Immunocompromised pediatric patients | 20 | Japanese | Increased AUC, C0 and Cmax | [40] | |||

| Healthy males | 52 | Increased AUC and Cmax | [35] | ||||

| Proven or probable invasive fungal infection or prophylasis | 55 | Indian | Increased C0 | [38] | |||

| Healthy males | 18 | Japanese | Increased AUC and Cmax | <0.01 | [58] | ||

| Pediatric patients receiving voriconazole | 37 | Japanese | When combined with IMs, increased C0 vs NMs+UMs (grouped together). | One patient: syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), high C0, discontinuation | 0.004 | [39] | |

| IM | Healthy | 20 | White | Increased AUC and MRT; decreased CL | <0.05 | [14] | |

| Healthy males | 18 | Chinese | Decreased AUC and t1/2, increased CL vs PMs. No significant differences vs NMs. | [33] | |||

| Cystic fibrosis with lung transplantation; curative or preemptive VCZ | 24 | White | Decreased VCZ dose; increased VCZ overdose rate | ≤0.022 | [43] | ||

| No association with adverse drug reactions | 0.4 | ||||||

| Healthy males | 18 | Korean | Increased AUC, C0 and Cmax | <0.008 | [34] | ||

| Suspected fungal retinitis | 1 | Indian | Elevated C0 | Hallucinations, abnormal liver function tests, withholding of VCZ followed by reintroduction at lower dose | [46] | ||

| Immunocompromised pediatric cancer patients with invasive fungal infection or VCZ prophylaxis | 33 | Increased C0/D | 0.04 | [18] | |||

| Septic shock with Candida krusei on blood culture | 1 | Reduced dosage of VCZ | [45] | ||||

| Proven or probable invasive fungal infection | 144 | Increased C0/CN. Significantly increased VCZ C0 and C0/CN vs PMs | <0.05 | [21] | |||

| Hematological malignancy receiving presumptive or definitive VCZ therapy | 19 | Increased C0 | Highest rates of clinical toxicity, highest median number of dose adjustments (no PMs in study) | [44]a | |||

| Healthy males | 52 | Increased AUC and Cmax | [35] | ||||

| Healthy males | 18 | Japanese | Increased AUC and Cmax | <0.05 | [58] | ||

| Pediatric patients receiving voriconazole | 37 | Japanese | When combined with PMs, increased C0 vs NMs+UMs (grouped together) | One patient: liver function abnormality, dose reduction | 0.004 | [39] | |

| Suspected or proven invasive fungal infections | 35 | White | Increased C0, t1/2, decreased CL, Ke | <0.05 | [19] | ||

| UM | Healthy males | 20 | Chinese | *1/*17: Decreased AUC and Cmax; increased CL | <0.05 | [17] | |

| Suspected disseminated fungal infection | 1 | White | *17/*17: Subtherapeutic C0 despite dose increase | *17/*17: VCZ discontinuation and switch to caspofungin | [50] | ||

| Sepsis secondary to Burkholderia cepacia infection | 1 | *1/*17: Undetectable VCZ concentrations | [47] | ||||

| Immunocompromised pediatric cancer patients with invasive fungal infection or VCZ prophylaxis | 33 | *17/*17: Decreased C0/D | 0.02 | [18] | |||

| *1/*17: No significant difference in C0/D | 0.95 | ||||||

| Suspected disseminated Aspergillosis infection | 1 | African | *1/*17: Subtherapeutic C0 | [49] | |||

| Proven or probable invasive fungal infection | 144 | *1/*17: Decreased C0 | [21] | ||||

| Hematological malignancy receiving presumptive or definitive VCZ therapy | 19 | *1/*17 + *17/*17: Decreased C0 | [44] | ||||

| Pulmonary invasive aspergillosis | 1 | *17: Undetectable levels | *17: Lack of response; VCZ discontinuation | [48] | |||

| Refractory aspergillosis | 1 | White | *17/*17: Low C0 | *17/*17: Switch to caspofungin | [51] | ||

| ICU patients | 6 | White | *1/*17: Decreased C0 | [27] | |||

| Lung transplant patients | 177 | *1/*17 + *17/*17b: Increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma | 0.03 | [22] | |||

| Suspected or proven invasive fungal infections | 35 | White | *1/*17 + *17/*17: Increased dose, decreased C0 and C0/D | <0.001 | [19] |

2 patients with *2/*17 included in this group.

It is unclear from the paper whether patients with the *2/*17 and *3/*17 genotypes were included or excluded from this group of genotypes.

AUC: area under the concentration-time curve; C0: trough concentrations; C0/D: dose-adjusted trough concentrations; CL: clearance; Cmax: maximum plasma concentrations; CN: ratio of voriconazole trough concentrations to concentration of voriconazole-N-oxide; Ke: elimination rate constant; MRT: mean residence time; Tmax: time to maximum plasma concentrations; t1/2: half-life; VCZ: voriconazole.

CYP2C19

Since CYP2C19 is the primary enzyme responsible for the metabolism of voriconazole, almost all pharmacogenetic studies on the drug have focused on the contribution of CYP2C19 genotypes or resulting metabolic phenotypes. The CYP2C19 gene is highly polymorphic, with over 30 known variant alleles (http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2c19.htm). However, the majority of individuals will carry the *1, *2, *3 or *17 alleles. The CYP2C19*1 allele is associated with a normal-functioning CYP2C19 enzyme, while CYP2C19*2 (rs4244285; 19154G>A) and *3 (rs4986892; 17948G>A) are the most common alleles associated with enzymatic loss-of-function [25]. The *2 allele varies in frequency between populations, with frequencies of approximately 15% in Caucasians, 18% in African Americans and 29–34% in Asians. The *3 allele is much rarer, with frequencies of approximately 0.6% in Caucasians, 0.3% in African Americans, and 2–9% in Asians. Other alleles have also been associated with significantly decreased or no function (e.g.*4–*10), but they are very rare, with frequencies typically below 1% across ethnicities [26]. Additionally, their functional status with specific regard to voriconazole has not been studied. The CYP2C19*17 allele (rs12248560; −806C>T) results in increased activity of the enzyme, with frequencies of approximately 22% in Caucasians, 19% in African Americans, 2% in East Asians and 17% in South or Central Asians [26]. For more information on CYP2C19 alleles, their functionality and their population frequencies, please refer to the gene-specific information table page for CYP2C19 on PharmGKB at https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2c19RefMaterials.

Based on presence of these alleles, individuals can be categorized as CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizers (UM), normal metabolizers (NM), intermediate metabolizers (IM; also referred to as heterozygous extensive metabolizers (HEM)) or poor metabolizers (PM). Individuals who are NMs are homozygous for the CYP2C19*1 allele and have a normally functioning enzyme. Those who are IMs carry one *1 allele and a loss-of-function allele (e.g. *1/*2), which produces an enzyme with reduced function. PMs carry two loss-of-function alleles (e.g. *2/*2), resulting in low or deficient CYP2C19 enzyme activity. UMs carry the *17 allele without a loss-of-function allele (i.e. *1/*17 or *17/*17), resulting in increased CYP2C19 enzyme activity [25]. Though most studies have categorized *1/*17 as an ultrarapid metabolizer [21, 27], it is occasionally grouped with the normal metabolizer phenotype [28]. Individuals who carry a loss-of-function allele and a gain-of-function allele (e.g. *2/*17) are typically classified as IMs [26, 29].

Poor metabolizers

Across 17 studies and one meta-analysis, poor metabolizers were consistently found to have reduced metabolism leading to increased concentrations of voriconazole as compared to NMs [14, 16–18, 20, 21, 23, 30–40]; one study and a meta-analysis found that PMs had reduced metabolism as compared to IMs [23, 33]. However, very little evidence exists for an effect of PM genotypes on clinical outcome. One case report noted a patient with the *2/*2 genotype who discontinued voriconazole due to highly elevated levels [36]. Another case report on an individual with the *2/*2 genotype noted that the drug was discontinued due to QTc prolongation occurring while the drug was at toxic levels. However, the study stated that the QTc prolongation might have been due to other causes, such as electrolyte abnormalities [37]. A larger study on pediatric patients reported one PM patient with high voriconazole levels who developed syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and discontinued the drug [39]. Several studies have found no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of drug toxicities (e.g. hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal effects, photosensitization) between PMs and other metabolizer phenotypes [28, 41, 42], including the meta-analysis previously discussed above [23].

Intermediate metabolizers

Nine studies report an association between intermediate metabolizers and voriconazole metabolism and concentrations [14, 18, 19, 34, 39, 43], though several did not conduct statistical analyses [35, 44, 45]. However, almost every study found that IMs had decreased voriconazole metabolism and increased concentrations as compared to NMs. Two exceptions were a study by Shi et al. that found no significant difference in AUC, half-life or clearance between IMs and NMs [33], and a study by Wang et al. that found no significant difference in trough concentrations between IMs and NMs, though they did find a significantly increased ratio of voriconazole trough concentrations to voriconazole N-oxide concentrations in IMs compared to NMs [21]; no explanation is provided within these studies regarding the contradictory findings. As with PMs, very little evidence exists for an effect of IM genotypes on clinical outcome. One case report noted an individual with the *1/*2 genotype who required a dose reduction due to high trough concentrations [45], and another case report noted an individual with the *1/*2 genotype who had elevated concentrations accompanied by hallucinations and abnormal liver function tests. The latter patient’s adverse effects resolved after stopping voriconazole treatment, and reintroduction at a lower dose was uncomplicated [46]. A study in pediatrics reported one IM patient with liver function abnormality who required a dose reduction [39]. As previously stated under the Poor metabolizers section, no additional studies have reported a statistically significant association between CYP2C19 genetic variations and voriconazole-related adverse events. Most reports to date have been of singular patients or case reports.

Ultrarapid metabolizers

Ten studies have looked at the effect of UM genotypes on the metabolism and plasma concentrations of voriconazole [17–19, 21, 27, 44, 47–50], with five focusing exclusively on the *1/*17 genotype [17, 21, 27, 47, 49]. One study found that those with the *1/*17 genotype had statistically significantly increased clearance as compared to NMs [17]. Two additional studies also found that those with the *1/*17 genotype had decreased concentrations of voriconazole as compared to NMs or PMs, but neither conducted statistical analyses [21, 27]. Additionally, two case reports noted subtherapeutic or undetectable levels of the drug in those with the *1/*17 genotype [47, 49]. However, in one of these reports, a patient with chronic granulomatous disease had complicated results. The patient had exceptionally high voriconazole concentrations upon initial assessment, but subsequent voriconazole concentrations were so low as to be undetectable; the authors suggest this may be the result of CYP450 enzyme downregulation by inflammation [47]. In contrast to these reports, a study in pediatric patients by Hicks et al. found no statistically significant difference in voriconazole dose-adjusted trough concentrations between those with the *1/*17 genotype and those with the *1/*1 genotype [18].

Literature evidence on the effect of the *17/*17 genotype on voriconazole levels is sparse. However, the same pediatric study by Hicks et al. found that those with the *17/*17 genotype did have statistically significantly lower dose-adjusted trough concentrations of voriconazole as compared to those with the *1/*1 genotype (four patients with this genotype were present in the study) [18]. Two case reports support this association, one describing an individual who had undetectable levels of drug, prompting a discontinuation of voriconazole and switch to an alternative drug [50], and the other describing an individual with acute leukemia who had a lack of response and a failure to reach therapeutic concentrations, also prompting discontinuation and switch to caspofungin [51]. However, in the former case study, the authors noted that the patient was co-medicated with carbamazepine, a known CYP2C19 inducer, and therefore the individual contributions of the genotype and co-medication cannot be distinguished [50]. In the latter study, the authors state that co-medications and disease-induced modulation of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 cannot be excluded as explanations for the low voriconazole concentrations [51].

Additionally, one study in lung transplant patients found that those with the *1/*17 or *17/*17 genotypes had a statistically significantly increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) when receiving voriconazole [22]. SCC can lead to numerous cutaneous lesions, which may require surgery, and in some case, be fatal; voriconazole use is associated with a 73% increased risk of the disease in lung transplant recipients [52]. The authors of the study on CYP2C19 UMs and SCC suggest that the increased risk of SCC may be due to a link between the voriconazole N-oxide metabolite and DNA damage [22].

Genotype-directed dosing of voriconazole

Lamoureux et al. sought to determine the impact of CYP2C19 genotypes on the dose required to attain therapeutic voriconazole plasma concentrations in a cohort of 35 patients. They found that the therapeutic dose requirement did not differ between NMs and IMs or PMs. However, UMs had a significantly greater dose requirement as compared to NMs, and also showed an approximately 1.5-fold greater dose requirement as compared to IMs or PMs (UMs: 4.76±0.47 mg/kg twice daily vs. IMs/PMs: 3.03±0.36 mg/kg twice daily) [19]. A recent study by Teusink et al. compared standard dosing of voriconazole to genotype-directed dosing [24]. A pilot study followed 25 individuals undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) who received an initial dose of voriconazole of 5 mg/kg twice daily, regardless of genotype. Their doses were then adjusted until they were within the target therapeutic range of 1 – 5.5 ug/L. A subsequent study genotyped 20 individuals for CYP2C19 *2, *3 and *17 prior to administering voriconazole, and adjusted the initial voriconazole dose based on their genotype as follows: IMs or unknown metabolizers received 6 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours, and NMs or UMs received 7 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours. No PMs were present and only one UM (*1/*17) was present in the genotype-directed dosing arm. Doses were then adjusted, as in the pilot study, until they were within the target range. Comparison of the genotype-directed dosing arm to the standard dosing arm showed that patients in the genotype-directed dosing arm took a median of 6.5 days to reach the target therapeutic range, while patients in the standard dosing arm took a median of 29 days, a statistically significant difference [24].

Other genes

While CYP3A4, CYP2C9 and members of the FMO family all contribute to the metabolism of voriconazole, there is very limited evidence for an association between variants within the genes that encode these enzymes and concentrations or pharmacokinetic parameters of voriconazole. One study found that those with the AG genotype at rs4646437 in the CYP3A4 gene had significantly higher concentrations of voriconazole as compared to those with the GG genotype [53]. The functional role of the rs4646437 SNP is yet to be determined, but opposing findings have been reported in studies involving tacrolimus, cyclosporine and finasteride – those with the GG genotype were observed to have the highest concentrations of these drugs, followed by the AG genotype and then the AA genotype [54, 55]. CYP2C9 also plays a role in voriconazole metabolism, but a single case report on an individual with the *2/*2 (poor metabolizer) genotype found similar pharmacokinetic parameters when compared against healthy volunteers with the *1/*1 genotype [56]. To date, there are no studies investigating the effect of FMO family variants on voriconazole metabolism or response.

Conclusions

While a reasonable amount of literature evidence supports an association between CYP2C19 genotype and voriconazole exposure, these supporting studies are mostly underpowered. Larger studies may be necessary to ascertain a more definitive link between the gene and drug. However, feasibility of such large studies can be hindered by the difficulty of finding enough patients who are PMs, IMs or UMs; international collaborations could assist in recruiting patients with diverse CYP2C19 phenotypes. Additionally, findings connecting CYP2C19 polymorphisms to voriconazole clinical outcomes and adverse events have not been consistent. Hence, more studies are needed to address this potential association. While one study did prospectively genotype CYP2C19 and showed a faster achievement of target voriconazole concentrations, this conclusion is limited due to the study’s small size, lack of PMs, and having only a single UM participant in the genotype-directed dosing arm [24]. These issues with the current body of literature warrant further research into this topic given the high morbidity and mortality rates of failed antifungal therapy in immunocompromised patients. Recently published guidelines by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) [57] providing therapeutic recommendations for voriconazole based on CYP2C19 genotype may help clinicians in delivering more accurate dosing, possibly preventing delays in treatment optimization or unwanted adverse events.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the NIH/NIGMS (R24 GM61374) and NIH/NHGRI (U01HG006380).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

RBA is a stockholder in Personalis Inc. and a paid advisor for Pfizer and Karius. TEK is a paid scientific advisor to the Rxight™ Pharmacogenetics Program

This paper uses the term “normal metabolizer” in place of the term “extensive metabolizer (EM)” in accordance with the 2016 publication by Caudle et al. entitled “Standardizing terms for clinical pharmacogenetic test results: consensus terms from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)”.

References

- 1.Kousha M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:156–174. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lass-Florl C. Triazole antifungal agents in invasive fungal infections: a comparative review. Drugs. 2011;71:2405–2419. doi: 10.2165/11596540-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohr J, Johnson M, Cooper T, Lewis JS, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Current options in antifungal pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:614–645. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascual A, Calandra T, Bolay S, Buclin T, Bille J, Marchetti O. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with invasive mycoses improves efficacy and safety outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:201–211. doi: 10.1086/524669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owusu Obeng A, Egelund EF, Alsultan A, Peloquin CA, Johnson JA. CYP2C19 polymorphisms and therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole: are we ready for clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics? Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:703–718. doi: 10.1002/phar.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu HY, Jain R, Xie H, Pottinger P, Fredricks DN. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: retrospective cohort study of the relationship to clinical outcomes and adverse events. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inc S. VORICONAZOLE – voriconazole injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inc SC. Voriconazole. 50 mg and 200 mg Tablets. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theuretzbacher U, Ihle F, Derendorf H. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of voriconazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:649–663. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyland R, Jones BC, Smith DA. Identification of the cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the N-oxidation of voriconazole. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:540–547. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanni SB, Annaert PP, Augustijns P, Bridges A, Gao Y, Benjamin DK, Jr, Thakker DR. Role of flavin-containing monooxygenase in oxidative metabolism of voriconazole by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1119–1125. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murayama N, Imai N, Nakane T, Shimizu M, Yamazaki H. Roles of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 in methyl hydroxylated and N-oxidized metabolite formation from voriconazole, a new anti-fungal agent, in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:2020–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roffey SJ, Cole S, Comby P, Gibson D, Jezequel SG, Nedderman AN, Smith DA, Walker DK, Wood N. The disposition of voriconazole in mouse, rat, rabbit, guinea pig, dog, and human. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:731–741. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholz I, Oberwittler H, Riedel KD, Burhenne J, Weiss J, Haefeli WE, Mikus G. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and bioavailability of the triazole antifungal agent voriconazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotype. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:906–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourcier K, Hyland R, Kempshall S, Jones R, Maximilien J, Irvine N, Jones B. Investigation into UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzyme kinetics of imidazole- and triazole-containing antifungal drugs in human liver microsomes and recombinant UGT enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:923–929. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.030676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikus G, Schowel V, Drzewinska M, Rengelshausen J, Ding R, Riedel KD, Burhenne J, Weiss J, Thomsen T, Haefeli WE. Potent cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype-related interaction between voriconazole and the cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitor ritonavir. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Lei HP, Li Z, Tan ZR, Guo D, Fan L, Chen Y, Hu DL, Wang D, Zhou HH. The CYP2C19 ultra-rapid metabolizer genotype influences the pharmacokinetics of voriconazole in healthy male volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:281–285. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hicks JK, Crews KR, Flynn P, Haidar CE, Daniels CC, Yang W, Panetta JC, Pei D, Scott JR, Molinelli AR, et al. Voriconazole plasma concentrations in immunocompromised pediatric patients vary by CYP2C19 diplotypes. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1065–1078. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamoureux F, Duflot T, Woillard JB, Metsu D, Pereira T, Compagnon P, Morisse-Pradier H, El Kholy M, Thiberville L, Stojanova J, Thuillez C. Impact of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on voriconazole dosing and exposure in adult patients with invasive fungal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zonios D, Yamazaki H, Murayama N, Natarajan V, Palmore T, Childs R, Skinner J, Bennett JE. Voriconazole metabolism, toxicity, and the effect of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1941–1948. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T, Zhu H, Sun J, Cheng X, Xie J, Dong H, Chen L, Wang X, Xing J, Dong Y. Efficacy and safety of voriconazole and CYP2C P19 polymorphism for optimised dosage regimens in patients with invasive fungal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams K, Arron ST. Association of CYP2C19 *17/*17 Genotype With the Risk of Voriconazole-Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Yu C, Wang T, Chen K, Zhai S, Tang H. Effect of cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphisms on the clinical outcomes of voriconazole: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:1185–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teusink A, Vinks A, Zhang K, Davies S, Fukuda T, Lane A, Nortman S, Kissell D, Dell S, Filipovich A, Mehta P. Genotype-Directed Dosing Leads to Optimized Voriconazole Levels in Pediatric Patients Receiving Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Shuldiner AR, Hulot JS, Thorn CF, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for cytochrome P450 family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 19. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:159–165. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834d4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hicks JK, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, Muller DJ, Ji Y, Leckband SG, Leeder JS, Graham RL, Chiulli DL, LL A, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98:127–134. doi: 10.1002/cpt.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weigel JD, Hunfeld NG, Koch BC, Egal M, Bakker J, van Schaik RH, van Gelder T. Gain-of-function single nucleotide variants of the CYP2C19 gene (CYP2C19*17) can identify subtherapeutic voriconazole concentrations in critically ill patients: a case series. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:2013–2014. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SH, Lee DG, Kwon JC, Lee HJ, Cho SY, Park C, Kwon EY, Park SH, Choi SM, Choi JH, Yoo JH. Clinical Impact of Cytochrome P450 2C19 Genotype on the Treatment of Invasive Aspergillosis under Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Voriconazole in a Korean Population. Infect Chemother. 2013;45:406–414. doi: 10.3947/ic.2013.45.4.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, Hulot JS, Mega JL, Roden DM, Klein TE, Sabatine MS, Johnson JA, Shuldiner AR, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317–323. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda Y, Umemura K, Kondo K, Sekiguchi K, Miyoshi S, Nakashima M. Pharmacokinetics of voriconazole and cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:587–588. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss J, Ten Hoevel MM, Burhenne J, Walter-Sack I, Hoffmann MM, Rengelshausen J, Haefeli WE, Mikus G. CYP2C19 genotype is a major factor contributing to the highly variable pharmacokinetics of voriconazole. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:196–204. doi: 10.1177/0091270008327537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei HP, Wang G, Wang LS, Ou-yang DS, Chen H, Li Q, Zhang W, Tan ZR, Fan L, He YJ, Zhou HH. Lack of effect of Ginkgo biloba on voriconazole pharmacokinetics in Chinese volunteers identified as CYP2C19 poor and extensive metabolizers. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:726–731. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi HY, Yan J, Zhu WH, Yang GP, Tan ZR, Wu WH, Zhou G, Chen XP, Ouyang DS. Effects of erythromycin on voriconazole pharmacokinetics and association with CYP2C19 polymorphism. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:1131–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0869-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, Kim BH, Nam WS, Yoon SH, Cho JY, Shin SG, Jang IJ, Yu KS. Effect of CYP2C19 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of voriconazole after single and multiple doses in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:195–203. doi: 10.1177/0091270010395510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung H, Lee H, Han H, An H, Lim KS, Lee Y, Cho JY, Yoon SH, Jang IJ, Yu KS. A pharmacokinetic comparison of two voriconazole formulations and the effect of CYP2C19 polymorphism on their pharmacokinetic profiles. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2609–2616. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S80066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moriyama B, Falade-Nwulia O, Leung J, Penzak SR, JJ C, Huang X, Henning SA, Wilson WH, Walsh TJ. Prolonged half-life of voriconazole in a CYP2C19 homozygous poor metabolizer receiving vincristine chemotherapy: avoiding a serious adverse drug interaction. Mycoses. 2011;54:e877–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriyama B, Jarosinski PF, Figg WD, Henning SA, Danner RL, Penzak SR, Wayne AS, Walsh TJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous voriconazole in obese patients: implications of CYP2C19 homozygous poor metabolizer genotype. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:e19–22. doi: 10.1002/phar.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chawla PK, Nanday SR, Dherai AJ, Soman R, Lokhande RV, Naik PR, Ashavaid TF. Correlation of CYP2C19 genotype with plasma voriconazole levels: a preliminary retrospective study in Indians. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:925–930. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narita A, Muramatsu H, Sakaguchi H, Doisaki S, Tanaka M, Hama A, Shimada A, Takahashi Y, Yoshida N, Matsumoto K, et al. Correlation of CYP2C19 phenotype with voriconazole plasma concentration in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:e219–223. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182880eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mori M, Kobayashi R, Kato K, Maeda N, Fukushima K, Goto H, Inoue M, Muto C, Okayama A, Watanabe K, Liu P. Pharmacokinetics and safety of voriconazole intravenous-to-oral switch regimens in immunocompromised Japanese pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1004–1013. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04093-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsumoto K, Ikawa K, Abematsu K, Fukunaga N, Nishida K, Fukamizu T, Shimodozono Y, Morikawa N, Takeda Y, Yamada K. Correlation between voriconazole trough plasma concentration and hepatotoxicity in patients with different CYP2C19 genotypes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levin MD, den Hollander JG, van der Holt B, Rijnders BJ, van Vliet M, Sonneveld P, van Schaik RH. Hepatotoxicity of oral and intravenous voriconazole in relation to cytochrome P450 polymorphisms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1104–1107. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berge M, Guillemain R, Tregouet DA, Amrein C, Boussaud V, Chevalier P, Lillo-Lelouet A, Le Beller C, Laurent-Puig P, Beaune PH, et al. Effect of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype on voriconazole exposure in cystic fibrosis lung transplant patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0914-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trubiano JA, Crowe A, Worth LJ, Thursky KA, Slavin MA. Putting CYP2C19 genotyping to the test: utility of pharmacogenomic evaluation in a voriconazole-treated haematology cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1161–1165. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calcagno A, Baietto L, Pagani N, Simiele M, Audagnotto S, D’Avolio A, De Rosa FG, Di Perri G, Bonora S. Voriconazole and atazanavir: a CYP2C19-dependent manageable drug-drug interaction. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1281–1286. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suan D, O’Connor K, Booth DR, Liddle C, Stewart GJ. Voriconazole toxicity related to polymorphisms in CYP2C19. Intern Med J. 2011;41:364–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Autmizguine J, Krajinovic M, Rousseau J, Theoret Y, Litalien C, Marquis C, Tapiero B, Ovetchkine P. Pharmacogenetics and beyond: variability of voriconazole plasma levels in a patient with primary immunodeficiency. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:1961–1965. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abidi MZ, D’Souza A, Kuppalli K, Ledeboer N, Hari P. CYP2C19*17 genetic polymorphism–an uncommon cause of voriconazole treatment failure. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;83:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bouatou Y, Samer CF, Ing Lorenzini KR, Daali Y, Daou S, Fathi M, Rebsamen M, Desmeules J, Calmy A, Escher M. Therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole: a case report of multiple drug interactions in a patient with an increased CYP2C19 activity. AIDS Res Ther. 2014;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malingre MM, Godschalk PC, Klein SK. A case report of voriconazole therapy failure in a homozygous ultrarapid CYP2C19*17/*17 patient comedicated with carbamazepine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:205–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennis Y, Bodeau S, Bouquie R, Deslandes G, Verstuyft C, Gruson B, Andrejak M, Lemaire-Hurtel AS, Chouaki T. High metabolic N-oxidation of voriconazole in a patient with refractory aspergillosis and CYP2C19*17/*17 genotype. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:782–784. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mansh M, Binstock M, Williams K, Hafeez F, Kim J, Glidden D, Boettger R, Hays S, Kukreja J, Golden J, et al. Voriconazole Exposure and Risk of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Aspergillus Colonization, Invasive Aspergillosis and Death in Lung Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:262–270. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He HR, Sun JY, Ren XD, Wang TT, Zhai YJ, Chen SY, Dong YL, Lu J. Effects of CYP3A4 polymorphisms on the plasma concentration of voriconazole. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:811–819. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li CJ, Li L, Lin L, Jiang HX, Zhong ZY, Li WM, Zhang YJ, Zheng P, Tan XH, Zhou L. Impact of the CYP3A5, CYP3A4, COMT, IL-10 and POR genetic polymorphisms on tacrolimus metabolism in Chinese renal transplant recipients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chau CH, Price DK, Till C, Goodman PJ, Chen X, Leach RJ, Johnson-Pais TL, Hsing AW, Hoque A, Tangen CM, et al. Finasteride concentrations and prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geist MJ, Egerer G, Burhenne J, Mikus G. Safety of voriconazole in a patient with CYP2C9*2/CYP2C9*2 genotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3227–3228. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00551-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moriyama B, Obeng AO, Barbarino J, Penzak SR, Henning SA, Scott SA, Agundez JA, Wingard JR, McLeod HL, Klein TE, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC(R)) Guideline for CYP2C19 and Voriconazole Therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cpt.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imamura CK, Furihata K, Okamoto S, Tanigawara Y. Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus when coadministered with voriconazole. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:408–413. doi: 10.1002/jcph.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]