Abstract

Background and purpose

Sugar- and artificially-sweetened beverage intake have been linked to cardiometabolic risk factors, which increase the risk of cerebrovascular disease and dementia. We examined whether sugar- or artificially-sweetened beverage consumption were associated with the prospective risks of incident stroke or dementia in the community-based Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort.

Methods

We studied 2888 participants aged over 45 for incident stroke (mean age 62 [SD, 9] years; 45% men) and 1484 participants aged over 60 for incident dementia (mean age 69 [SD, 6] years; 46% men). Beverage intake was quantified using a food frequency questionnaire at cohort examinations 5 (1991–1995), 6 (1995–1998) and 7 (1998–2001). We quantified recent consumption at examination 7 and cumulative consumption by averaging across examinations. Surveillance for incident events commenced at examination 7 and continued for 10-years. We observed 97 cases of incident stroke (82 ischemic) and 81 cases of incident dementia (63 consistent with Alzheimer’s disease [AD]).

Results

After adjustments for age, sex, education (for analysis of dementia), caloric intake, diet quality, physical activity and smoking, higher recent and higher cumulative intake of artificially-sweetened soft drinks were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, all-cause dementia, and AD dementia. When comparing daily cumulative intake to <1 per week (reference), the hazard ratios were 2.96 (95% CI, 1.26–6.97) for ischemic stroke and 2.89 (95% CI, 1.18–7.07) for AD. Sugar-sweetened beverages were not associated with stroke or dementia.

Conclusions

Artificially-sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with a higher risk of stroke and dementia.

Keywords: Sugar, soft drinks, stroke, dementia, Framingham Heart Study

Journal Subject Codes: [8] Epidemiology

Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverages are associated with cardiometabolic diseases1, 2, which may increase the risk of stroke and dementia.3, 4 Limited prior findings suggest that sugar- and artificially-sweetened beverages are both associated with an increased risk of incident stroke,5 although conflicting findings have been reported.6 To our knowledge, studies are yet to examine the associations between sugary beverage consumption and the risk of incident dementia. Accordingly, we examined whether sugar- or artificially-sweetened soft drinks were associated with the 10-year risks of incident stroke and dementia in the community-based Framingham Heart Study. We also examined total sugary beverages, which combined sugar-sweetened soft drinks with non-carbonated high sugar beverages such as fruit juices and fruit drinks.

Methods

The Framingham Heart Study comprises a series of community-based prospective cohorts originating from the town of Framingham, Massachusetts, USA. We studied the Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort, which commenced in 1971 with the enrollment of 5124 volunteers. Participants have been studied across 9 examination cycles approximately every four years, with the latest cycle concluding in 2014.

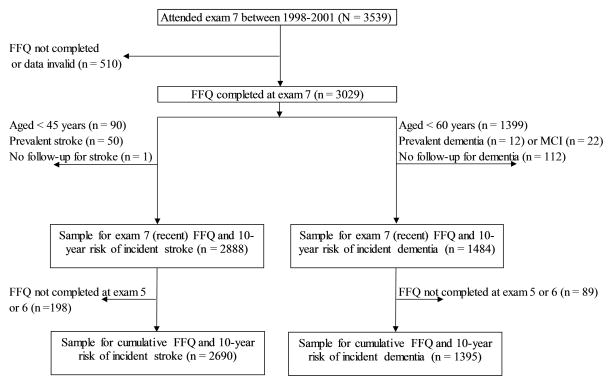

We estimated the 10-year risk of both incident stroke and dementia beginning from the 7th examination cycle (1998–2001). For the study of stroke in relation to beverage intake, we excluded persons with prevalent stroke or other significant neurological disease at baseline and those younger than 45 years. For investigating the incidence of dementia, we excluded persons with prevalent dementia, mild cognitive impairment or other significant neurological disease at baseline and those younger than 60 years. These age cut-offs are consistent with our prior work in this area.3 There were 2888 and 1484 participants available for analysis of incident stroke and new-onset dementia, respectively (Figure 1). All participants provided written informed consent, and the study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston University School of Medicine.

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants. The risk of incident stroke and dementia were calculated as the 10-year risk, starting from examination cycle 7. FFQ = food frequency questionnaire, MCI = mild cognitive impairment. Cumulative intake was calculated by averaging responses across the FFQ completed at examination cycles 5, 6 and 7 (to be included a participant must have had examination cycle 7 data and at least one of examination cycles 5 or 6).

Assessment of sugary beverage intake

Participants completed the Harvard semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) at examination cycles 5 (1991–1995), 6 (1995–1998), and 7 (1998–2001). The FFQ provides a validated measure of dietary intake over the past 12 months.7 Participants responded according to how frequently they consumed one glass, bottle, or can of each sugary beverage item, on average, across the previous year. The FFQ included 3 items on sugar-sweetened soft drink, 4 items on fruit juice, 1 item on non-carbonated sugar-sweetened fruit drinks and 3 items on artificially-sweetened soft drinks. Each item was scored according to 9 responses spanning from ‘never or less than 1 per month’ to ‘6+ per day’. Intake of soft drinks using the FFQ has been validated against dietary records (correlation coefficients of 0.81 for Coke/Pepsi)8, 9 and is reliable when readministered after 12 months (correlation coefficients of 0.85 for Coke/Pepsi).8, 9

We combined FFQ items to create variables reflecting intake of (I) total sugary beverages (combining sugar-sweetened soft drinks, fruit juice and fruit drinks), (II) sugar-sweetened soft drinks (high-sugar carbonated beverages such as cola), and (III) artificially-sweetened soft drinks (sugar-free carbonated beverages such as diet cola). We created new intake categories to ensure an adequate number of participants were retained in each intake group across each variable. Cut-points were determined before conducting the main analyses based on the relative distribution of intake for each variable. Total sugary beverage consumption was examined as < 1/day (reference), 1–2/day and >2/day; Sugar-sweetened soft drink intake was examined as 0/week (reference), up to 3/week and >3/week; and artificially-sweetened soft drink intake was examined as 0/week (reference), up to 6/week and ≥1/day. We used FFQ data obtained from examination cycle 7 as a measure of recent intake. In an additional analysis, we also averaged responses across examination cycles 5, 6 and 7 to calculate cumulative intake over a maximum of 7 years. For this later variable, we averaged FFQ data from examination cycle 7 with FFQ data from at least one other examination (5 or 6). However, we averaged across all 3 examination cycles where possible (72% of participants completed all 3 FFQs; n = 935 for stroke analysis sample and n = 755 for dementia analysis sample).

Incident Stroke and dementia

We related beverage consumption to the 10-year risk of stroke and dementia. Surveillance commenced from examination cycle 7 to the time of incident event over a maximum of 10 years or until last known contact with the participant. We defined stroke as the rapid onset of focal neurological symptoms of presumed vascular origin, lasting >24 hours or resulting in death. A diagnosis of dementia was made in line with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.10 A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia was based on the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the AD and Related Disorders Association for definite, probable, or possible AD.11 Please see the online-only Data Supplement for complete details on our methods of surveillance, diagnosis, and case ascertainment.

Statistical analysis

We used SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) to estimate Cox proportional hazards regression models (after confirming the assumption of proportionality of hazards). Recent intake and cumulative intake of total sugary beverages, sugar-sweetened soft drinks, and artificially-sweetened soft drinks were related separately to the risk of all stroke, ischemic stroke, all-cause dementia, and AD dementia. Hazard Ratios (HR) are presented accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We first performed minimally adjusted statistical models which included adjustments for age, sex, education (for analysis of dementia only) and total caloric intake (Model 1). Next, we stepped in adjustments for lifetyle factors including the Dietary Guidelines Adherence Index (DGAI; a variable quantifying adherence to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans) as a measure of overall diet quality12, self-reported physical activity,13 and smoking status (Model 2). A third statistical model included the adjustments outlined in Model 1 as well as additional cardiometabolic variables that may be influenced by sugary beverage intake1, 2, 14, 15 or associated with an increased risk of stroke or dementia.3, 4, 16 These variables included systolic blood pressure, treatment of hypertension, prevalent cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, prevalent diabetes mellitus, positivity for at least one apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele (for analysis of dementia only) and waist to hip ratio (Model 3). All covariates were obtained from examination cycle 7. We report Models 2 and 3 as our primary analyses (please see Supplemental Tables I–II online for Model 1 results).

We explored for interactions between beverage consumption and important confounders including waist to hip ratio, APOE ε4 allele status, and prevalent diabetes. We considered results statistically significant if a two-sided p < 0.05, except for tests of interaction which were considered statistically significant if a two-sided p < 0.1.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed mediation analyses to examine if any of the following covariates mediated the observed associations between cumulative intake of artificially-sweetened soft drink and the outcomes: prevalent hypertension, prevalent cardiovascular disease, prevalent diabetes, waist to hip ratio, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol.

Results

Table 1 displays cohort characteristics classified by total sugary beverage and artificially-sweetened soft drink intake for the larger stroke study sample (See Supplemental Table III for a summary of the dementia study sample). Total caloric intake increased across categories of total sugary beverage but not artificially-sweetened soft drink intake categories. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and diabetes decreased with more frequent consumption of total sugary beverages but increased with greater consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drink.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics at examination cycle 7 for the stroke study sample (N=2888)

| Total Sugary Beverages

|

Artificially-Sweetened Soft Drinks

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1/day | 1–2/day | >2/day | 0/week | 1–6/week | ≥1/day | |

| N (%) | 1317 (46) | 1103 (38) | 468 (16) | 1343 (47) | 1024 (35) | 519 (18) |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 61 (9) | 63 (9) | 62 (10) | 63 (9) | 63 (8) | 60 (8) |

| Male, n (%) | 533 (40) | 521 (47) | 248 (53) | 573 (43) | 458 (45) | 270 (52) |

| No HS degree | 54 (4) | 40 (4) | 14 (3) | 61 (5) | 28 (3) | 19 (4) |

| Waist/Hip, ratio, median (Q1, Q3) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.89, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) |

| BMI, ratio, median (Q1, Q3) | 28 (25, 31) | 27 (24, 30) | 27 (24, 31) | 27 (24, 30) | 28 (25, 31) | 29 (26, 33) |

| SBP, mmHg | 127 (19) | 128 (19) | 127 (18) | 127 (19) | 128 (19) | 127 (18) |

| Rx Hyp, n (%) | 453 (34) | 382 (35) | 148 (32) | 407 (30) | 372 (36) | 204 (39) |

| TC, mg/dL | 203 (37) | 200 (37) | 199 (37) | 203 (37) | 200 (37) | 197 (36) |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 55 (18) | 54 (17) | 51 (15) | 55 (17) | 54 (17) | 52 (16) |

| DM, n (%) | 187 (15) | 128 (12) | 36 (8) | 94 (7) | 145 (15) | 112 (22) |

| AF, n (%) | 40 (3) | 57 (5) | 17 (4) | 44 (3) | 42 (4) | 28 (5) |

| CVD, n (%) | 157 (12) | 126 (11) | 45 (10) | 135 (10) | 125 (12) | 68 (13) |

| Smoker*, n (%) | 182 (14) | 114 (10) | 56 (12) | 204 (15) | 91 (9) | 57 (11) |

| APOE ε4†, n (%) | 287 (22) | 242 (22) | 107 (23) | 286 (22) | 225 (22) | 123 (24) |

| PAI, units, median (Q1, Q3) | 36 (33, 41) | 37 (33, 41) | 37 (34, 42) | 37 (34, 42) | 37 (33, 41) | 36 (33, 40) |

| Total caloric intake, Cal/day | 1647 (539) | 1839 (548) | 2257 (612) | 1840 (608) | 1767 (573) | 1869 (590) |

| DGAI, units | 9 (3) | 10 (3) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | 10 (3) | 9 (3) |

| Saturated fat, gm/d | 21 (10) | 22 (9) | 25 (11) | 22 (10) | 21 (10) | 23 (10) |

| Trans fat, gm/d | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Omega-3, gm/d | 11 (5) | 12 (5) | 13 (6) | 12 (6) | 11 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Dietary fiber, gm/d | 17 (8) | 19 (7) | 21 (8) | 18 (8) | 18 (8) | 18 (7) |

| Alcohol, gm/d | 11 (17) | 10 (14) | 9 (13) | 10 (16) | 10 (15) | 10 (15) |

Mean (SD) reported unless specified otherwise. AF = atrial fibrillation; CVD = prevalent cardiovascular disease; DGAI = dietary guidelines adherence index; DM = diabetes mellitus; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HS = high school; PAI = physical activity index; Rx Hyp= treatment for hypertension; SBP = systolic blood pressure; TC = total cholesterol.

defined as current smoker,

presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele.

Sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption was as follows: never, 1539 (53%); up to 3 times/week, 936 (32%); ≥3 times/week, 412 (14%).

Sweetened beverage consumption and the risk of stroke

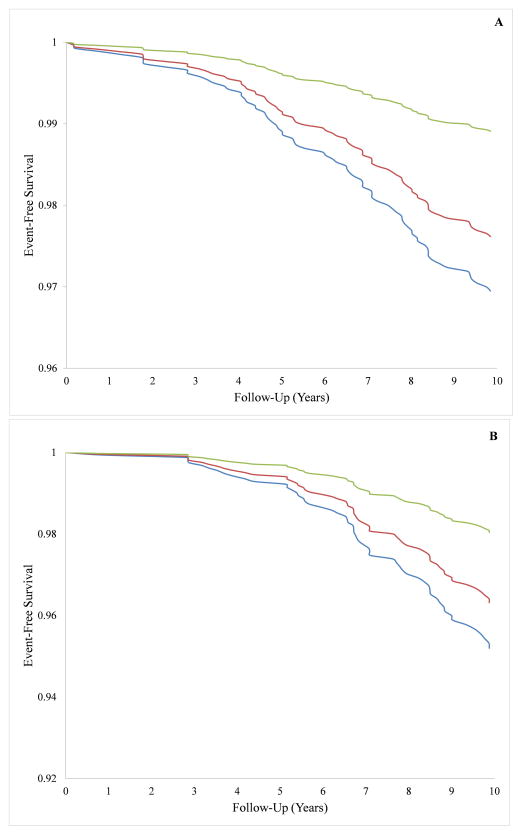

Greater recent consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drink was associated with an increased risk of stroke, with the strongest associations observed for ischemic stroke (Table 2). Higher cumulative intake of artificially-sweetened soft drink was also associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke (Table 2, Figure 2). Neither intake of total sugary beverages nor sugar-sweetened soft drink were associated with the risks of stroke.

Table 2.

Beverage intake and the risk of stroke

| Model | Recent Intake

|

Cumulative Intake

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Stroke

|

Ischemic Stroke

|

All Stroke

|

Ischemic Stroke

|

||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Total Sugary Beverages | |||||||||

| <1/day (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| 1–2/day | 1.12 (0.67, 1.88) | 0.65 | 1.06 (0.61, 1.82) | 0.84 | 1.09 (0.65, 1.81) | 0.75 | 0.90 (0.51, 1.58) | 0.71 | |

| >2/day | 1.29 (0.65, 2.55) | 0.47 | 0.86 (0.38, 1.91) | 0.70 | 0.75 (0.33, 1.69) | 0.49 | 0.60 (0.24, 1.49) | 0.27 | |

| <1/day (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| 1–2/day | 1.15 (0.73, 1.81) | 0.55 | 1.14 (0.70, 1.85) | 0.61 | 1.22 (0.77, 1.94) | 0.40 | 1.16 (0.70, 1.92) | 0.58 | |

| >2/day | 1.22 (0.65, 2.29) | 0.54 | 0.92 (0.44, 1.93) | 0.83 | 0.88 (0.42, 1.83) | 0.73 | 0.70 (0.30, 1.65) | 0.41 | |

| Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks | |||||||||

| 0/week (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| >0–3/week | 1.15 (0.71, 1.88) | 0.57 | 1.11 (0.65, 1.89) | 0.72 | 1.17 (0.70, 1.97) | 0.55 | 1.12 (0.63, 1.99) | 0.69 | |

| >3/week | 0.69 (0.29, 1.62) | 0.40 | 0.69 (0.27, 1.73) | 0.43 | 0.61 (0.25, 1.49) | 0.28 | 0.61 (0.23, 1.61) | 0.32 | |

| 0/week (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| >0–3/week | 1.22 (0.78, 1.92) | 0.38 | 1.25 (0.76, 2.04) | 0.38 | 1.14 (0.70, 1.85) | 0.60 | 1.20 (0.70, 2.05) | 0.51 | |

| >3/week | 0.88 (0.43, 1.78) | 0.71 | 0.84 (0.38, 1.86) | 0.67 | 0.80 (0.38, 1.67) | 0.55 | 0.81 (0.36, 1.83) | 0.61 | |

| Artificially-Sweetened Soft Drinks | |||||||||

| 0/week (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| >0–6/week | 2.09 (1.24, 3.51) | 0.005 | 2.47 (1.39, 4.40) | 0.002 | 1.78 (0.98, 3.23) | 0.06 | 2.62 (1.26, 5.45) | 0.01 | |

| ≥1/day | 1.95 (1.02, 3.73) | 0.045 | 2.27 (1.11, 4.64) | 0.03 | 1.87 (0.90, 3.90) | 0.10 | 2.96 (1.26, 6.97) | 0.01 | |

| 0/week (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| >0–6/week | 1.83 (1.14, 2.93) | 0.01 | 2.02 (1.19, 3.43) | 0.01 | 1.59 (0.92, 2.75) | 0.10 | 1.98 (1.03, 3.78) | 0.01 | |

| ≥1/day | 1.97 (1.10, 3.55) | 0.02 | 2.34 (1.24, 4.45) | 0.01 | 1.79 (0.91, 3.52) | 0.09 | 2.59 (1.21, 5.57) | 0.01 | |

Model 1 is reported in the online supplement. Model 2 adjusts for age, sex, total caloric intake, the dietary guidelines adherence index, self-reported physical activity, and smoking status. Model 3 adjusts for age, sex, total caloric intake, systolic blood pressure, treatment of hypertension, prevalent cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, prevalent diabetes mellitus, and waist to hip ratio. For recent intake: N/events for all strokes were 76/2225 for Model 2 and 93/2729 for Model 3. N/events for ischemic stroke were 64/2225 for Model 2, 78/2729 for Model 3. For cumulative intake: N/events for all strokes were 70/2137 for Model 2 and 85/2598 for Model 3. N/events for ischemic stroke were 58/2137 for Model 2 and 70/2598 for Model 3.

Figure 2.

Cumulative consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drinks and event-free survival of incident (a) all stroke and (b) all-cause dementia. Green, red and blue lines denote intake of <1/week, 1–6/week, and ≥1/day, respectively. Incidence curves are adjusted for age, sex, and total caloric intake (as well as education for dementia as an outcome).

Sweetened beverage consumption and the risk of dementia

When examining cumulative beverage consumption, daily intake of artificially-sweetened soft drink was associated with an increased risk of both all-cause dementia and AD dementia in Models 1 and 2 (Table 3, Supplemental Table II). However, such associations were no longer significant after adjustment for the covariates outlined in Model 3. With respect to recent beverage intake, daily intake of artificially-sweetened beverages was associated with an increased risk of dementia in Model 2 only. Neither total sugary beverages nor sugar-sweetened soft drink was associated with the risks of dementia.

Table 3.

Beverage intake and the risk of dementia

| Model | Recent Intake

|

Cumulative Intake

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Dementia

|

AD Dementia

|

All-Cause Dementia

|

AD Dementia

|

||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Total Sugary Beverages | |||||||||

| <1/day (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| 1–2/day | 0.92 (0.53, 1.58) | 0.75 | 0.95 (0.51, 1.78) | 0.88 | 0.72 (0.41, 1.27) | 0.26 | 0.69 (0.35, 1.33) | 0.26 | |

| >2/day | 1.23 (0.59, 2.58) | 0.59 | 1.75 (0.81, 3.81) | 0.16 | 0.59 (0.24, 1.47) | 0.26 | 0.78 (0.31, 2.01) | 0.61 | |

| <1/day (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| 1–2/day | 1.09 (0.67, 1.76) | 0.73 | 1.21 (0.69, 2.13) | 0.50 | 0.86 (0.52, 1.40) | 0.53 | 0.89 (0.50, 1.59) | 0.69 | |

| >2/day | 1.19 (0.58, 2.44) | 0.63 | 1.90 (0.89, 4.05) | 0.10 | 0.61 (0.25, 1.53) | 0.29 | 0.92 (0.36, 2.38) | 0.87 | |

| Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks | |||||||||

| 0/week (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| >0–3/week | 0.86 (0.48, 1.51) | 0.59 | 0.91 (0.47, 1.74) | 0.77 | 0.75 (0.42, 1.33) | 0.32 | 0.88 (0.45, 1.70) | 0.69 | |

| >3/week | 1.15 (0.49, 2.68) | 0.75 | 1.56 (0.64, 3.76) | 0.33 | 0.82 (0.35, 1.96) | 0.66 | 1.23 (0.50, 3.06) | 0.65 | |

| 0/week (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| >0–3/week | 1.06 (0.64, 1.77) | 0.82 | 1.11 (0.62, 2.00) | 0.73 | 0.80 (0.48, 1.33) | 0.39 | 0.88 (0.49, 1.59) | 0.68 | |

| >3/week | 0.94 (0.41, 2.13) | 0.87 | 1.30 (0.56, 3.04) | 0.54 | 0.77 (0.35, 1.70) | 0.52 | 0.91 (0.37, 2.24) | 0.84 | |

| Artificially-Sweetened Soft Drinks | |||||||||

| 0/week (ref) | 2 | ||||||||

| >0–6/week | 1.39 (0.79, 2.43) | 0.25 | 1.48 (0.78, 2.82) | 0.23 | 1.41 (0.77, 2.59) | 0.27 | 1.68 (0.82, 3.43) | 0.15 | |

| ≥1/day | 2.20 (1.09, 4.45) | 0.03 | 2.53 (1.15, 5.56) | 0.02 | 2.47 (1.15, 5.30) | 0.02 | 2.89 (1.18, 7.07) | 0.02 | |

| 0/week (ref) | 3 | ||||||||

| >0–6/week | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) | 0.99 | 1.05 (0.59, 1.87) | 0.87 | 1.30 (0.74, 2.29) | 0.36 | 1.66 (0.86, 3.20) | 0.13 | |

| ≥1/day | 1.08 (0.54, 2.17) | 0.83 | 1.29 (0.59, 2.80) | 0.53 | 1.70 (0.80, 3.61) | 0.17 | 2.03 (0.83, 4.97) | 0.12 | |

Model 1 is reported in the online supplement. Model 2 adjusts for age, sex, total caloric intake, education, the dietary guidelines adherence index, self-reported physical activity, and smoking status. Model 3 adjusts for age, sex, education, total caloric intake, systolic blood pressure, treatment of hypertension, prevalent cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, prevalent diabetes mellitus, waist to hip ratio, and positivity for at least one APOE ε4 allele. For recent intake: N/events for all-cause dementia were 66/1135 for Model 2 and 81/1348 for Model 3. N/events for AD dementia were 52/1135 for Model 2 and 63/1348 for Model 3. For cumulative intake: N/events for all-cause dementia were 61/1087 for Model 2 and 75/1285 for Model 3. N/events for AD dementia were 47/1087 for Model 2 and 57/1285 for Model 3.

Interactions

We did not observe any interactions with waist-to-hip ratio, diabetes status or the presence of the APOE ε4 allele with intake of any beverage examined.

Mediation analysis

Prevalent diabetes status was identified as a potential mediator of the association between artificially-sweetened beverage intake and the risk of both incident all-cause dementia and AD dementia (Please see supplemental results online). When repeating the primary analysis excluding those with prevalent diabetes and adjusting for Model 1 covariates, daily intake of artificially-sweetened beverages (versus no intake) remained a significant predictor of both incident all-cause dementia (HR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.07–5.59, N/events, 53/1148) and AD dementia (HR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.22–8.52, N/events, 40/1148). Thus, diabetes was a partial but not full mediator of the association between artificially-sweetened beverage intake and incident dementia. Prevalent hypertension was a potential mediator of the association between artificially-sweetened beverage intake and incident all-stroke, but not ischemic stroke (Please see supplemental results online). After excluding persons with prevalent hypertension, and after adjustment for Model 1 covariates, the association between artificially-sweetened beverage intake and incident all-stroke was attenuated (0/week, reference; >0–6/week, HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 0.58, 4.02; ≥1/day, HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.40–5.11; N/events, 23/1456). No other mediation was identified.

Discussion

In our community-based cohort, higher consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drink was associated with an increased risk of both stroke and dementia. Neither total sugary beverages nor sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with the risks of stroke or dementia.

The Nurses Heath Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study reported that greater consumption of sugar- and artificially-sweetened soft drinks were each independently associated with a higher risk of incident stroke over 28 years of follow-up for women (N = 84085) and 22 years of follow-up for men (N= 43371).5 The Northern Manhattan Study, a population-based multiethnic cohort (N=2564), reported that daily consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drink was associated with a higher risk of combined vascular events but not stroke when examined as an independent outcome.6 Our study provides further evidence to link consumption of artificially-sweetened beverages with the risk of stroke, particularly ischemic stroke. To our knowledge, our study is the first to report an association between daily intake of artificially-sweetened soft drink and an increased risk of both all-cause dementia and dementia due to AD.

Our observation that artificially-sweetened, but not sugar-sweetened, soft drink consumption was associated with an increased risk of stroke and dementia is quite intriguing. Sugar-sweetened beverages provide a high dose of added sugar leading to a rapid spike in blood glucose and insulin,17 providing a plausible mechanism to link consumption to the development of stroke and dementia risk factors. Like sugar-sweetened soft drinks, artificially-sweetened soft drinks are associated with risk factors for stroke and dementia,1, 14, 15 although the mechanisms are incompletely understood, and inconsistent findings have been reported.18

Artificially-sweetened beverages are typically sweetened with non-nutritive sweeteners such as saccharin, acesulfame, aspartame, neotame or sucralose. At the time of FFQ administration in this study, saccharin, acesulfame-K, and aspartame were FDA approved whereas sucralose was approved in 1999, neotame in 2002 and stevia in 2008.18 Collectively, these synthetic substances are much more potent than sucrose, with only trace amounts needed to generate the sensation of sweetness.17

Previous studies linking artificially-sweetened beverage consumption to negative health consequences have been questioned based on concerns regarding residual confounding and reverse causality, whereby sicker individuals consume diet beverages as a means of negating a further deterioration in health.19 Indeed, in our study, diabetes - a known risk factor for dementia 20 - was more prevalent in those who regularly consumed artificially-sweetened soft drinks. Diabetes status also partially mediated the association between artificially-sweetened soft drink intake and incident dementia. As our study was observational, we are unable to determine whether artificially-sweetened soft drink intake increased the risk of incident dementia through diabetes or whether persons with diabetes were simply more likely to consume diet beverages. Some studies have provided evidence for the former.21 Artificial sweeteners have been shown to cause glucose intolerance in mice by altering gut microbiota and are associated with dysbiosis and glucose intolerance in humans.21 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that artificially-sweetened beverage consumption was associated with incident diabetes, although publication bias and residual confounding were considered possible.14 Clinical trials are needed to establish whether the consumption of artificially-sweetened beverages is causally related to dementia or surrogate endpoints such as cognitive decline or brain atrophy.

In our study, prevalent hypertension, the single most important stroke risk factor, attenuated the association between artificially-sweetened beverage intake and incident all-stroke, although not ischemic stroke. Prospective cohort studies, such as the Nurses Health Study, have demonstrated associations between higher intake of artificially-sweetened beverages and an increased risk of incident hypertension.22 However, it remains unclear whether artificial sweeteners cause hypertension or whether diet beverages are favored by those most at risk. Given that clinical trials involving stroke end points are large and costly, clinical trials should investigate whether artificially-sweetened beverages are associated with important stroke risk factors such as high blood pressure.

Limitations of the study include the absence of ethnic minorities, which limits the generalizability of our findings to populations of non-European decent. Secondly, the observational nature of our study precludes us from inferring causal links between artificially-sweetened beverage consumption and the risks of stroke and dementia. Third, the use of a self-report FFQ to obtain dietary intake data may be subject to recall bias thus introducing error into our estimated models. Fourth, although we addressed confounding in numerous ways, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. Lastly, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons meaning that some findings may be attributable to chance.

In conclusion, artificially-sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with an increased risk of stroke and dementia. Sugar-sweetened beverages were not associated with an increased risk of such outcomes. As the consumption of artificially-sweetened soft drinks is increasing in the community,23 along with the prevalence of stroke24 and dementia,25 future research is needed to replicate our findings and to investigate the mechanisms underlying the reported associations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Dr. Pase is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1089698). The Framingham Heart Study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract no. N01-HC-25195 and no. HHSN268201500001I) and by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG054076, R01 AG049607, R01 AG033193, U01 AG049505, U01 AG052409) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS017950 and UH2 NS100605). Funds from the USDA Agricultural Research Service Agreement No. 58-1950-4-003 supported in part the collection of dietary data for this project and the efforts of Dr. Jacques. Department of Medicine and Evan’s Foundation’s Evans Scholar Award to Dr. Vasan Ramachandran.

Footnotes

Disclosures - All other authors report no disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB, et al. Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation. 2007;116:480–488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1037–1042. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pase MP, Beiser A, Enserro D, Xanthakis V, Aparicio H, Satizabal CL, et al. Association of ideal cardiovascular health with vascular brain injury and incident dementia. Stroke. 2016;47:1201–1206. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein AM, de Koning L, Flint AJ, Rexrode KM, Willett WC. Soda consumption and the risk of stroke in men and women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95:1190–1199. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardener H, Rundek T, Markert M, Wright CB, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL. Diet soft drink consumption is associated with an increased risk of vascular events in the northern manhattan study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27:1120–1126. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1968-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;135:1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. American Journal of Clininical Nutrition. 1999;69:243–249. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: The effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;18:858–867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. American Psychatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2000. Text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M. Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease: Report of the nincds-adrda work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fogli-Cawley JJ, Dwyer JT, Saltzman E, McCullough ML, Troy LM, Jacques PF. The 2005 dietary guidelines for americans adherence index: Development and application. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136:2908–2915. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kannel WB, Sorlie P. Some health benefits of physical activity: The framingham study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1979;139:857–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. British Medical Journal. 2015;351:h3576. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler SPG, Williams K, Hazuda HP. Diet soda intake is associated with long-term increases in waist circumference in a biethnic cohort of older adults: The san antonio longitudinal study of aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63:708–715. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: A risk profile from the framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig DS. Artificially sweetened beverages: Cause for concern. JAMA. 2009;302:2477–2478. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner C, Wylie-Rosett J, Gidding SS, Steffen LM, Johnson RK, Reader D, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners: Current use and health perspectives. A scientific statement from the american heart association and the american diabetes association. Circulation. 2012;126:509–519. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31825c42ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattes RD, Popkin BM. Nonnutritive sweetener consumption in humans: Effects on appetite and food intake and their putative mechanisms. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1–14. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S, Peters SAE, Woodward M, Mejia Arango S, Batty GD, Beckett N, et al. Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for dementia in women compared with men: A pooled analysis of 2.3 million people comprising more than 100,000 cases of dementia. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:300–307. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkelmayer WC, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Curhan GC. Habitual caffeine intake and the risk of hypertension in women. JAMA. 2005;294:2330–2335. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.18.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sylvetsky AC, Welsh JA, Brown RJ, Vos MB. Low-calorie sweetener consumption is increasing in the united states. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;96:640–646. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Shafe ACE, Cowie MR. Uk stroke incidence, mortality and cardiovascular risk management 1999–2008: Time-trend analysis from the general practice research database. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000269. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and meta analysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.