Abstract.

Attenuation correction is essential for quantitative reliability of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. In time-of-flight (TOF) PET, attenuation sinogram can be determined up to a global constant from noiseless emission data due to the TOF PET data consistency condition. This provides the theoretical basis for jointly estimating both activity image and attenuation sinogram/image directly from TOF PET emission data. Multiple joint estimation methods, such as maximum likelihood activity and attenuation (MLAA) and maximum likelihood attenuation correction factor (MLACF), have already been shown that can produce improved reconstruction results in TOF cases. However, due to the nonconcavity of the joint log-likelihood function and Poisson noise presented in PET data, the iterative method still requires proper initialization and well-designed regularization to prevent convergence to local maxima. To address this issue, we propose a joint estimation of activity image and attenuation sinogram using the TOF PET data consistency condition as an attenuation sinogram filter, and then evaluate the performance of the proposed method using computer simulations.

Keywords: positron emission tomography, time-of-flight, image reconstruction, attenuation correction

1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is widely used in the diagnosis and prognosis of diseases in oncology, neurology, and cardiology. For quantitative, semiquantitative or even qualitative but artifact-free PET, attenuation correction (AC) is mandatory. In the early days, PET scanners were equipped with a transmission source, enabling direct measurement of attenuation correction factors (ACFs) or attenuation sinogram. However, the majority of the modern PET scanners are incorporated into larger multimodality systems that combine both molecular and anatomical imaging, including PET/magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and PET/computed tomography (CT). As these systems lack transmission sources, the ACF is usually computed from the anatomical image. In particular, the synthetic mapping from the MR image to PET ACF is a very difficult problem and still one of the major bottlenecks in PET-MR imaging. Furthermore, because of the smaller field of view (FOV) of MR compared with PET, the truncation of the attenuation sinogram (or ACFs) for a larger subject is also a challenging problem. Many segmentation and atlas-based methods have been developed; however, regardless of the number of tissue types used in the methods, MR-based AC continues to demonstrate limited performance. It is relatively easier to convert CT images to ACFs since both of them measure the attenuation of photons, although at different energy levels. However, the same attenuation sinogram truncation problem exists because of the smaller FOV of CT. In addition, because of the sequential nature of the PET/CT acquisition, there is misalignment between PET and ACFs generated by CT. Many methods have been developed to solve the truncation problem; however, none of them can avoid the so-called cross talk problem, where localized errors in the activity image are compensated by localized errors in the attenuation image.

To solve the AC problem, several groups have developed methods that jointly estimate AC and the activity from emission PET data.1–9 Different types of consistency conditions can be directly considered1,6,8–12 or indirectly imposed by maximizing the likelihood function.4,7 A similar approach has been also applied to PET/MR.13 Although some useful results have been obtained, these methods are generally disappointing because of the cross talk. This is essentially due to the lack of attenuation information in the emission measurement to uniquely determine the ACFs. Another emerging technology, time-of-flight (TOF) PET scanners, could potentially offer an elegant solution to the AC problem in both PET/MR and PET/CT. TOF PET measures the differential arrival time for each coincident photon pair, providing additional information about the position within the source volume from which a positron was emitted. The improved localization by TOF information leads to a previously unachievable SNR improvement in reconstructed images. Studies evaluating TOF PET scanners have shown significant noise reduction.14 In the clinic, this improvement translates to either scan time reduction or image quality improvement, as demonstrated in this work,15 where clearly improved lesion contrast was achieved using TOF data. A recent study in a large set of oncology patients found that human observers (radiologists) preferred TOF images in terms of contrast recovery, noise level, and clarity of anatomical details.16 More importantly, recent studies have shown that in TOF PET the artifacts induced by AC errors are less severe than that in non-TOF PET.17 This finding indicates that TOF PET data contain information about AC that is not present in non-TOF PET data, demonstrating a possibility to derive AC information from TOF PET measurements.

It has been recently shown18 that the attenuation sinogram can be reconstructed from TOF PET emission data generated from Radon transform through estimating the gradient of the attenuation sinogram using TOF PET data consistency condition. An analytical two-step method was also developed to compute AC in a seminar work by Defrise et al.,18 however, it is unstable for high-frequency components and also for regions with low photon counts, even in the perfect noise-free case. An iterative one-step method based on the same consistency condition was proposed by Li et al.19 and was recently extended to histoimage format of TOF data.20 As an alternative to using only consistency conditions of TOF data, some methods seek to iteratively estimate activity and attenuation information by solving a joint estimation problem. One such method is the maximum-likelihood activity and attenuation estimation technique, which simultaneously estimates activity and attenuation images, applied to TOF PET.13 Salomon et al.21 also proposed a related maximum-likelihood (ML) algorithm to assign attenuation values to MRI regions based on TOF PET data. A second group of methods comprises ML techniques applied to jointly estimate the ACFs instead of the attenuation image.22–25 Although these estimation methods using TOF information demonstrated improved results and the mathematical analysis of the continuous version of the problem showed that noise-free emission data determine the ACFs up to a constant, it is still unclear whether the uniqueness also applies to the Poisson likelihood, except if the TOF data are consistent. Furthermore, it is found that even with TOF PET data, the AC estimation problem is still underdetermined and the possible presence of other local maxima in the TOF likelihood still exists except the AC estimation close to the ground-truth is provided.

Exploiting the TOF information, the AC estimation for PET/MR or PET/CT is promising but still very challenging. Here, we proposed an elegant framework to address this challenge. We will explain the TOF data consistency condition and its maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation in Sec. 2. In Sec. 3, the maximum likelihood attenuation correction factor (MLACF) with a data consistency filtering will be derived. We validate the performance of the proposed method using simulation results in Sec. 4. Initialization and constant issues will be discussed in Sec. 5, and we conclude in Sec. 6.

2. Time-of-Flight Positron Emission Tomography Data Consistency Condition and Maximum a Posteriori Estimation

We denote the unattenuated TOF emission data as , where , , and are the radial, azimuthal, and TOF bin coordinates, respectively. The two-dimensional (2-D) TOF PET data consistency condition for noise-free is given by the following partial differential equation:26,27

| (1) |

where denotes the standard deviation of TOF Gaussian profile (i.e., ). Let be the attenuation sinogram along the line of response and be the attenuated TOF emission data, so-called TOF prompt data. Since , we can replace in Eq. (1) by and rewrite the equation as follows:

| (2) |

Defrise et al.18 have shown that for any line of response that , the two derivatives of can be determined from Eq. (2) and as a 2-D radon transform of a smooth image, can be determined by integration except a global constant within its sinogram support. Note that the sinogram support, , is the regions of interest with activity in emission sinogram; when , otherwise . is a small value that can be zero in noiseless case.

The above TOF PET data consistency condition of Eq. (2) is in the continuous format and only for noise-free data. We will first discretize Eq. (2) since our measurements are not continuous. We approximate the derivatives with finite central difference method and denote , , and as the differential operators along corresponding subscript. We then obtain a simple linear equation as follows:

| (3) |

where

| (4) |

where is a vector representing . , , and are the discretized vector of , , and , respectively. More specifically, let , , and for . , and , , and are the numbers of radial, azimuthal, and TOF bins, respectively. , and . Here, is the radial bin interval (mm), , and is the time bin interval (mm). , , and are also used for the differential operators of , , and that are the matrices .

Since can only be determined up to a constant , we can infer that

| (5) |

where , which can cause the boundary artifact when the scaling constant or the region of is not accurate. This indicates that as long as we have additional information about this constant, attenuation sinogram could be iteratively reconstructed by minimizing a properly defined cost function based on Eq. (3).

Denoting , the MAP estimate of attenuation sinogram can be expressed as

| (6) |

where is the prior probability density function of attenuation sinogram and is the likelihood function given by noise distribution of .

Note that both and are precomputed from TOF prompt emission data, and their noise distributions are very complicated due to multiple differentiations on Poisson-distributed data . Therefore as a simplification, we approximate the noise of as Gaussian distributed and formulate Eq. (6) as a penalized least-square data fitting problem

| (7) |

where is a quadratic penalty term. Equation (3) is very ill-posed because of the differential operators. Therefore, we designed the following algorithm to simultaneously estimate the activity and ACF incorporating with a filter based on TOF data consistency condition.

3. MLACF with Time-of-Flight Data Consistency Filtering

Let and denote the discretized activity image and attenuation sinogram, respectively, denotes the known TOF prompt measurement along the ’th line of response with TOF index , and denotes the TOF system matrix. The log-likelihood function, which accounts for the Poisson statistics within the measurement, can be written as

| (8) |

Here, we assume that the scatters and randoms are precorrected for the computational simplicity28 although the precorrected PET measurement becomes an approximation of Poisson distribution.

Since this function is obviously concave with respect to either or , the updating strategy in MLACF is to fix one of them and maximize the function with respect to the other one so that the objective function is monotonically increasing. When is fixed, the maximum-likelihood solution is obtained by a straight-forward maximum likelihood expectation maximization (MLEM) update. When is fixed, the maximum-likelihood solution is simply calculated as within the sinogram support. Because of the constant scaling factor, the maximum-likelihood estimators of and have many local optima depending on the initial value of , thus we will discuss the effect of initial values.

It is known that if the TOF PET data are consistent, then the MLACF estimation using noisy measurement can determine the ACF up to a constant. Therefore, we incorporate the data consistency filtering in each iteration, we force the intermediate results always as consistent as possible. We note that the same idea to apply bow-tie filter to force data consistency has been reported in the literature.29 Here, we demonstrate how we can design a least-square filter based on the data consistency condition in Eq. (3). More specifically, the proposed method can be summarized in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1.

The proposed method.

| 1: Initialize is a constant in a support and . |

| 2: fordo |

| 3: 1. Relaxed MLEM with |

| 4: fordo |

| 5: , |

| 6: , |

| 7: end for |

| 8: |

| 9: 2. Update attenuation sinogram |

| 10: , |

| 11: 3. Conjugate gradient with |

| 12: |

| 13: |

| 14: fordo |

| 15: |

| 16: |

| 17: |

| 18: |

| 19: |

| 20: |

| 21: end for |

| 22: |

| 23: ; stop update if or |

| 24: end for |

In the proposed MLACF with data consistency filtering, the quadratic penalty is used for estimation of both activity and attenuation. More specifically, is a three-dimensional (3-D) penalty with 26 neighbor voxels in Cartesian coordinate and is a 2-D penalty with eight neighbor pixels in sinogram domain with radial and angular directions. Relaxed MLEM with quadratic penalty is similar to the block sequential regularized expectation maximization algorithm.30 Here, is the relaxation factor and is the hyperparameter of quadratic function for the activity estimation. In the conjugate gradient method,31 the quadratic penalty is also similarly used as a sequential regularization. is the hyperparameter of quadratic function for the attenuation estimation. is the inner iteration number of updates for the MLEM and is the inner iteration number of conjugate gradient. is defined as a small number, such as 5 to 10 due to the fast convergence of the conjugate gradient. In Algorithm 1, except the consistency condition filtering (conjugate gradient execution), this is exactly the same as a conventional MLACF, which is used for the comparison in Secs. 4 and 5.

At the beginning of joint estimation, because the estimation of attenuation is far from the true value and therefore it takes more time to do the filtering, once the estimate is close to the true value and thus satisfies the data consistency condition, it needs less computational cost; more details of initial value effect will be discussed (see Sec. 5). The possible presence of other local maxima in the TOF likelihood still exists because of the nonconvexity of the joint cost function. Therefore, a good initialization is crucial.

4. Results

In the simulation study, we used the same geometry of a GE SIGNA TOF PET scanner with 450-ns timing resolution. The diameter of the scanner is 622.6 mm, and the number of radial and angular bins is 256 and 224, respectively. The number of TOF time bin is 27 and time bin spacing is 22.2 mm. To deal with the constant issue, we assume that the total number of counts is known,25 thus, we do not have a scaling issue in the simulation and focus on the performance of the data consistency filtering. For the validation, we used 2-D thorax and 3-D XCAT phantoms32 and compared the results of proposed method with the conventional MLACF.

To evaluate the proposed method, we first used a thorax phantom as described in Fig. 1. The true activity image and attenuation image are all of size and voxel size 0.234 cm. The attenuation coefficients are (i) for lung, (ii) for bone, and (iii) for tissue in Fig. 1(b). In the reconstruction, we used the TOF-based PET ray-driven forward and voxel-driven backward projectors as done by Kim et al.28,33,34

Fig. 1.

The ground-truth images of (a) activity, (b) attenuation, and (c) attenuation sinogram.

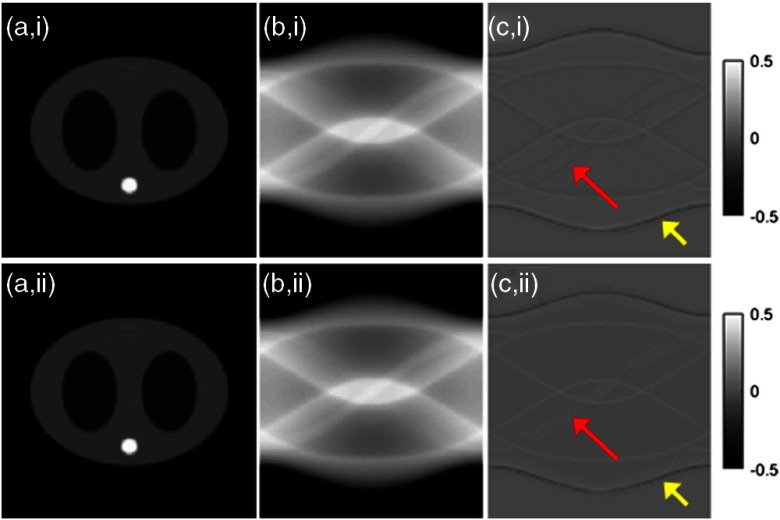

In the noiseless case of Fig. 2, the reconstructed activity images and the attenuation sinograms of the conventional MLACF and the proposed method were compared, which should be identical theoretically. Here, all penalty-related hyperparameters were set to zero, such as and in Algorithm 1. Both results were converged after few iterations with small differences, however, some patterns as pointed in Fig. 2(c) were slightly different. Mean square errors (MSEs) were almost the same in the noiseless case.

Fig. 2.

Noiseless case, all penalty-related hyperparameters are zero. (i) Conventional MLACF and (ii) the proposed method. (a) Activity image, (b) the attenuation sinogram, and (c) the difference image.

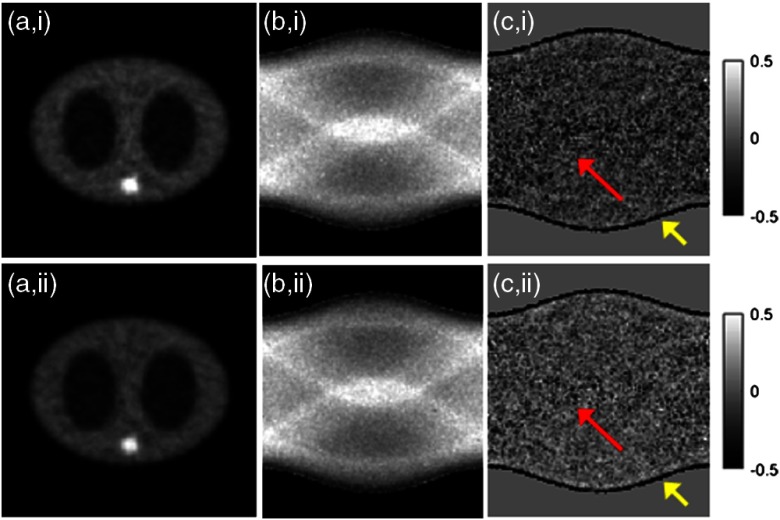

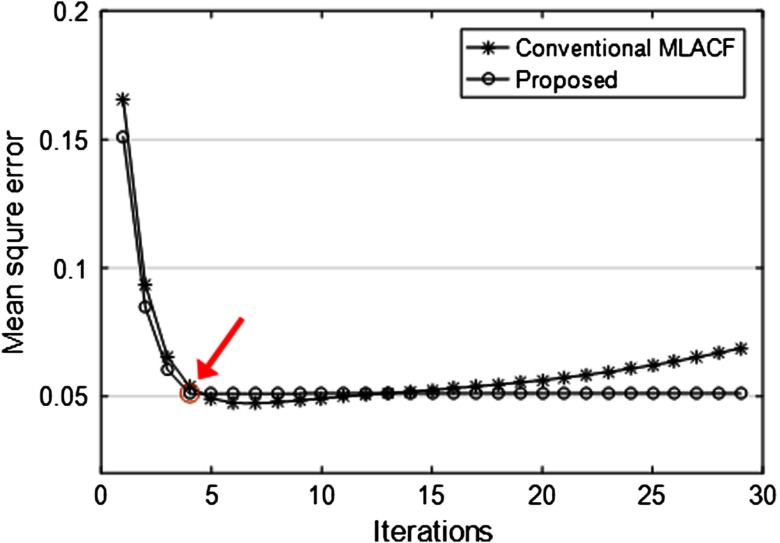

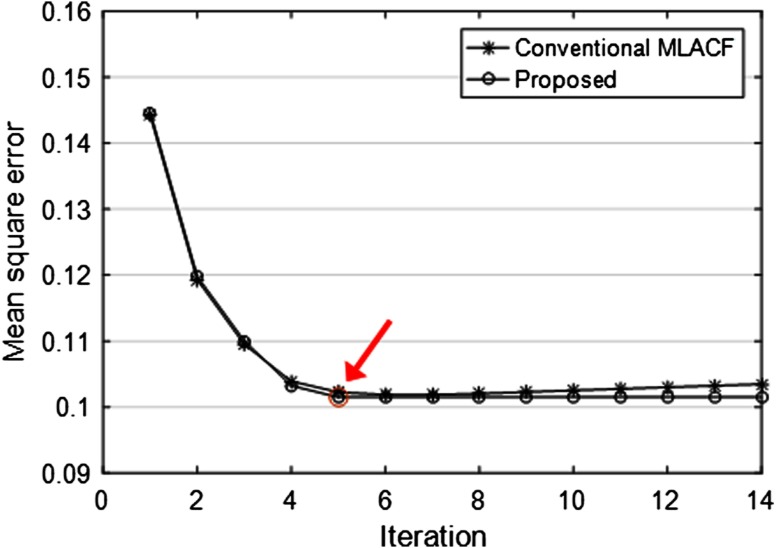

In the noisy case of Fig. 3, the reconstructed activity images and the attenuation sinograms of the conventional MLACF and the proposed method were compared. The number of total counts is about and the Poisson noise was imposed. Figure 3(c) of the conventional MLACF showed biases compared to the proposed method. Here, we stopped at 20 iterations before diverging too much for the conventional MLACF. MSEs of attenuation sinogram using the conventional MLACF and the proposed method were 0.056 and 0.051, respectively. We found that in noisy cases, although we determined reasonable hyperparameters for the quadratic penalty, the conventional MLACF was sensitive to noise, because the attenuation sinogram is directly acquired from the noisy prompt measurement, which affects to the activity image and the attenuation sinogram in the next iteration. More specifically, in Fig. 4, the MSEs of the conventional MLACF and the proposed method were compared by iteration. The proposed method converged in four iterations; however, the MSE of the conventional MLACF diverged after six iterations. After four iterations as pointed in Fig. 4, the proposed method stopped by the data consistency condition. We demonstrated that the proposed method was very useful to estimate the convergence in the noisy measurement.

Fig. 3.

Noisy case. (i) Conventional MLACF and (ii) the proposed method. (a) Activity image, (b) the attenuation sinogram, and (c) the difference image.

Fig. 4.

The MSE plots of attenuation sinograms using the conventional MLACF and the proposed method. Figure 3 showed the results at 20 iterations.

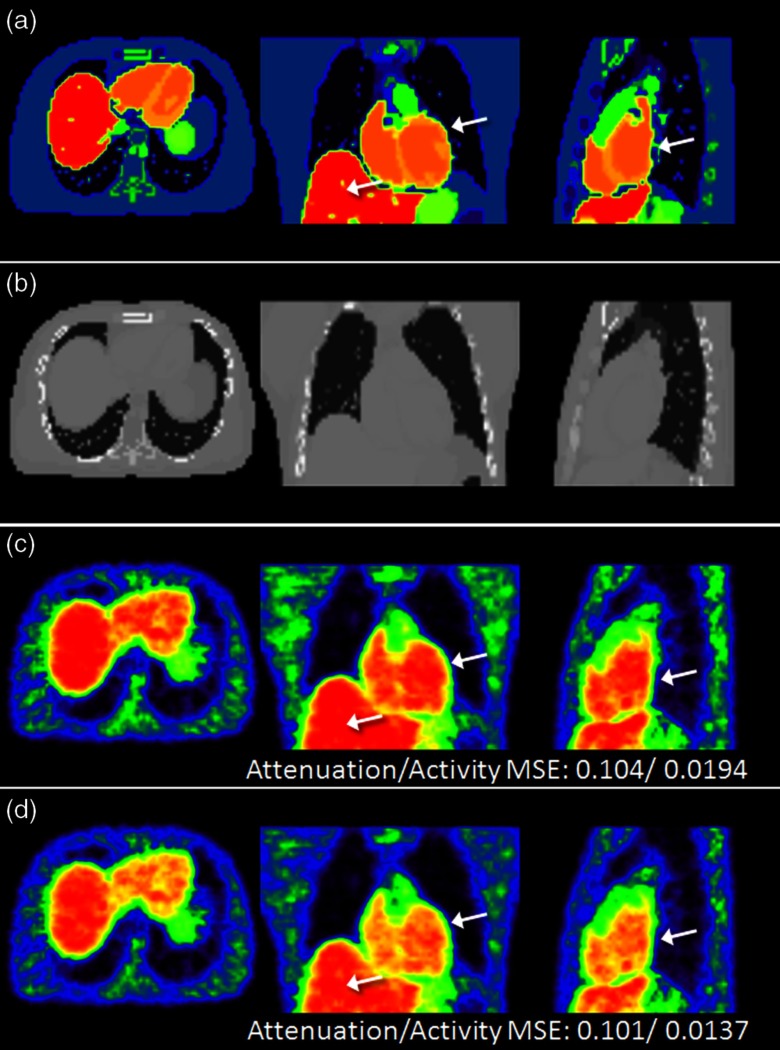

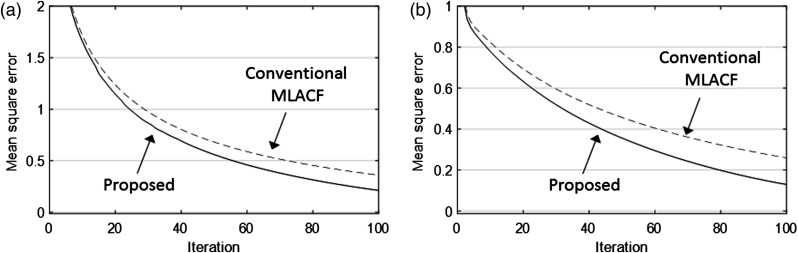

Furthermore, we performed a 3-D XCAT phantom simulation as shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The number of total counts is about and the Poisson noise was imposed. Figures 5(a) and 5(b) indicate the ground-truth images of activity and the attenuation. The reconstructed images of Figs. 5(c) and 5(d) using the conventional MLACF and the proposed method, respectively, were selected at 15 iterations. Here, we used the same hyperparameters for both methods. The MSEs of attenuation sinogram and activity image were 0.104 and 0.0194 for the conventional MLACF and 0.101 and 0.0137 for the proposed method, respectively. The MSE of attenuation sinogram using the proposed method is slightly smaller than the MSE using the conventional MLACF. Although the difference between two attenuation sinograms is small, the resulting activity images showed large bias. More specifically, the normalized difference of attenuation sinogram is less than 3% calculated by , however, the normalized difference of activity image is more than 40% calculated by . Here, and denote the activity images using the conventional MLACF and the proposed method, and and are the attenuation images using the conventional MLACF and the proposed method, respectively. We also can see the bias in the reconstructed image using the conventional MLACF as we pointed in Fig. 5(c). In Fig. 6, the proposed method converged at six iterations, however, the conventional MLACF diverged. Therefore, the proposed method using a data consistency filtering demonstrated great advantages of convergence and the improvement of image quality.

Fig. 5.

The ground-truth images of (a) activity and (b) attenuation, and the reconstructed activity images using (c) the conventional MLACF and (d) the proposed method. Here, MSEs correspond to the attenuation sinogram and the activity image.

Fig. 6.

The MSE plots of the conventional MLACF and the proposed method.

5. Discussion

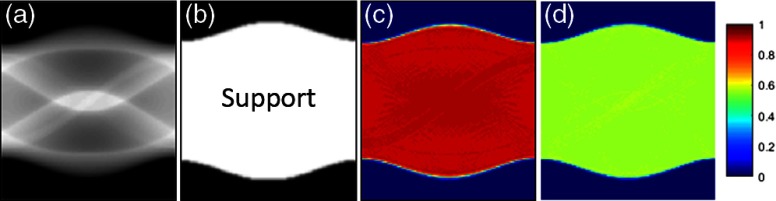

We have empathized the initialization and constant scaling issues of MLACF throughout the whole paper. Although the proposed method converged closer to the ground-truth compared to the conventional MLACF, the constant scaling issue still exists. Because of many local minima in the joint estimation of MLACF, the constant scaling is highly dependent on the initialization. In Fig. 7, we conducted simulations with the proposed method using different initializations of the attenuation sinogram in the noiseless case. The support region in Fig. 7(b) is estimated by the emission data as a region larger than a small value . As shown in Figs. 7(c) and 7(d), the different initialization values produce different constant scaling offsets. Comparing to the support region, the region of the constant value is exactly the same as the support region. Therefore, in the real case, the accurate support region is also important to the scaling of the attenuation sinogram.

Fig. 7.

(a) The ground-truth attenuation sinogram, (b) the support region (), difference of converged attenuation sinograms from initial value of (c) 0.5 and (d) 1.5. The constant offsets of (c) and (d) are close to 1 and 0.5.

In addition, with different initialization values, we compared the convergence plots of the conventional MLACF and the proposed method as shown in Fig. 8. The proposed method converged faster than the conventional MLACF. Therefore, the proposed method can provide not only the improvement of image quality but also fast convergence.

Fig. 8.

Convergence plots of the proposed method and the conventional MLACF using different initial values of (a) 0.5 and (b) 1.5.

We carefully examined the reasons of boundary artifact (yellow arrows in Figs. 2 and 3) in attenuation sinogram and the effect of boundary. One reason is that the sinogram support , defined by the region of , is difficult to set accurately at the boundary. Another reason is that the smoothing penalty can produce the boundary artifact. Comparing Figs. 2 and 3, we can see the small boundary artifact in the noiseless case; however, larger boundary artifact in the noisy case was shown due to the quadratic penalty. By conducting many experiments with various hyperparameters of the quadratic penalty, we concluded that the boundary effect does not significantly affect the activity image.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a formulation of the data consistency condition of TOF PET data and proposed a least-square filtering. We have also developed a joint estimation method using the TOF PET data consistency filtering to estimate the activity image and the attenuation sinogram simultaneously. The proposed method provided the improved image quality by the estimation of convergence and was validated via a pilot study based on the simulations using thorax and XCAT phantoms. The simulation results demonstrated the robustness of the proposed method to noise and shown its potential to achieve more accurate estimation of both activity image and attenuation sinogram. In the future, we will extend the TOF PET data consistency condition filtering with the scaling estimation for clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB); Award No. R01EB013293.

Biography

Biographies of the authors are not available.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Bronnikov A. V., “Reconstruction of attenuation map using discrete consistency conditions,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 19(5), 451–462 (2000). 10.1109/42.870255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Censor Y., et al. , “A new approach to the emission computerized tomography problem: simultaneous calculation of attenuation and activity coefficients,” IEEE Trans. Nuclear Sci. 26(2), 2775–2779 (1979). 10.1109/TNS.1979.4330535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Pierro A. R., Crepaldi F., “Activity and attenuation recovery from activity dataonly in emission computed tomography,” Comput. Appl. Math. 25(2–3), 205–227 (2006). 10.1590/S0101-82052006000200006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krol A., et al. , “An EM algorithm for estimating SPECT emission and transmission parameters from emission data only,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20(3), 218–232 (2001). 10.1109/42.918472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudo H., Nakamura H., “A new approach to SPECT attenuation correction without transmission measurements,” in Nuclear Science Symp., Vol. 2, pp. 13–58, IEEE; (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natterer F., “Determination of tissue attenuation in emission tomography of optically dense media,” Inverse Probl. 9(6), 731–736 (1993). 10.1088/0266-5611/9/6/009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuyts J., et al. , “Simultaneous maximum a posteriori reconstruction of attenuation and activity distributions from emission sinograms,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 18(5), 393–403 (1999). 10.1109/42.774167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panin V. Y., Zeng G. L., Gullberg G. T., “A method of attenuation map and emission activity reconstruction from emission data,” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 48(1), 131–138 (2001). 10.1109/23.910843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch A., et al. , “Toward accurate attenuation correction in SPECT without transmission measurements,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 16(5), 532–541 (1997). 10.1109/42.640743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natterer F., The Mathematics of Computerized Tomography, SIAM, Philadelphia: (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Defrise M., Liu X., “A fast rebinning algorithm for 3D positron emission tomography using John’s equation,” Inverse Probl. 15(4), 1047–1065 (1999). 10.1088/0266-5611/15/4/314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panin V. Y., et al. , “Application of discrete data consistency conditions for selecting regularization parameters in PET attenuation map reconstruction,” Phys. Med. Biol. 49(11), 2425–2436 (2004). 10.1088/0031-9155/49/11/021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezaei A., et al. , “Simultaneous reconstruction of activity and attenuation in time-of-flight PET,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 31(12), 2224–2233 (2012). 10.1109/TMI.2012.2212719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conti M., et al. , “First experimental results of time-of-flight reconstruction on an LSO PET scanner,” Phys. Med. Biol. 50(19), 4507–4526 (2005). 10.1088/0031-9155/50/19/006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karp J. S., et al. , “Benefit of time-of-flight in PET: experimental and clinical results,” J. Nucl. Med. 49(3), 462–470 (2008). 10.2967/jnumed.107.044834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti M., et al. , “Assessment of the clinical potential of a time-of-flight PET/CT scanner with less than 600 ps timing resolution,” Soc. Nucl. Med. 49(Suppl. 1), 411 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conti M., “Why is TOF PET reconstruction a more robust method in the presence of inconsistent data?” Phys. Med. Biol. 56(1), 155–168 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/1/010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Defrise M., Rezaei A., Nuyts J., “Time-of-flight PET data determine the attenuation sinogram up to a constant,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57(4), 885–899 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/4/885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H., El Fakhri G., Li Q., “Direct MAP estimation of attenuation sinogram using TOF PET emission data,” Soc. Nucl. Med. 54(Suppl. 2), 47 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y., et al. , “Transmission-less attenuation estimation from time-of-flight PET histo-images using consistency equations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 60(16), 6563–6583 (2015). 10.1088/0031-9155/60/16/6563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salomon A., et al. , “Simultaneous reconstruction of activity and attenuation for PET/MR,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 30(3), 804–813 (2011). 10.1109/TMI.2010.2095464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Defrise M., Rezaei A., Nuyts J., “Simultaneous reconstruction of attenuation and activity in TOF-PET: analysis of the convergence of the MLACF algorithm,” in Fully 3D Meeting (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Defrise M., Rezaei A., Nuyts J., “Transmission-less attenuation correction in time-of-flight PET: analysis of a discrete iterative algorithm,” Phys. Med. Biol. 59(4), 1073–1095 (2014). 10.1088/0031-9155/59/4/1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuyts J., Rezaei A., Defrise M., “ML-reconstruction for TOF-PET with simultaneous estimation of the attenuation factors,” in IEEE Nuclear Science Symp. and Medical Imaging Conf., pp. 2147–2149, IEEE; (2012). 10.1109/NSSMIC.2012.6551491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rezaei A., Defrise M., Nuyts J., “ML-reconstruction for TOF-PET with simultaneous estimation of the attenuation factors,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 33(7), 1563–1572 (2014). 10.1109/TMI.2014.2318175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Defrise M., et al. , “Continuous and discrete data rebinning in time-of-flight PET,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 27(9), 1310–1322 (2008). 10.1109/TMI.2008.922688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panin V. Y., Defrise M., Casey M. E., “Restoration of fine azimuthal sampling of measured TOF projection data,” in IEEE Nuclear Science Symp. and Medical Imaging Conf., pp. 3079–3084, IEEE; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim K., et al. , “Dynamic PET reconstruction using temporal patch-based low rank penalty for ROI-based brain kinetic analysis,” Phys. Med. Biol. 60(5), 2019–2046 (2015). 10.1088/0031-9155/60/5/2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren R., et al. , “Estimation of gap data using bow-tie filters for 3D time-of-flight PET,” in IEEE Nuclear Science Symp. and Medical Imaging Conf., pp. 2691–2694, IEEE; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Pierro A. R., Yamagishi M. B., “Fast EM-like methods for maximum ‘a posteriori’ estimates in emission tomography,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20(4), 280–288 (2001). 10.1109/42.921477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong E. K., Zak S. H., An Introduction to Optimization, Vol. 76, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey: (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segars W. P., et al. , “4D XCAT phantom for multimodality imaging research,” Med. Phys. 37(9), 4902–4915 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim K., Ye J. C., “Fully 3D iterative scatter-corrected OSEM for HRRT PET using a GPU,” Phys. Med. Biol. 56, 4991–5009 (2011). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/15/021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim K., et al. , “TOF-PET ordered subset reconstruction using non-uniform separable quadratic surrogates algorithm,” in Int. Symp. on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), pp. 963–966, IEEE; (2014). [Google Scholar]