Abstract

Background:

Compassion is considered an essential element in quality patient care. One of the conceptual challenges in healthcare literature is that compassion is often confused with sympathy and empathy. Studies comparing and contrasting patients’ perspectives of sympathy, empathy, and compassion are largely absent.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to investigate advanced cancer patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences of “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “compassion” in order to develop conceptual clarity for future research and to inform clinical practice.

Design:

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews and then independently analyzed by the research team using the three stages and principles of Straussian grounded theory.

Setting/participants:

Data were collected from 53 advanced cancer inpatients in a large urban hospital.

Results:

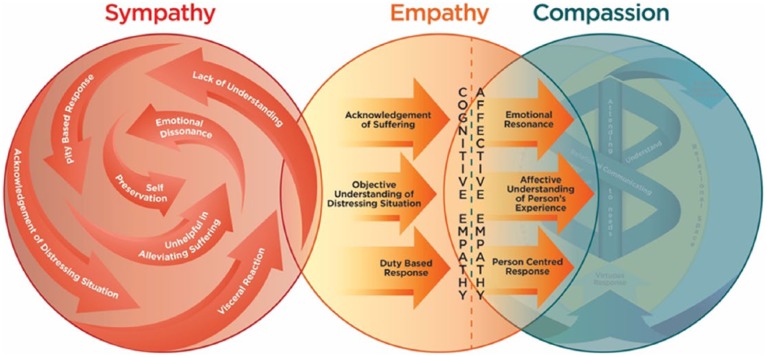

Constructs of sympathy, empathy, and compassion contain distinct themes and sub-themes. Sympathy was described as an unwanted, pity-based response to a distressing situation, characterized by a lack of understanding and self-preservation of the observer. Empathy was experienced as an affective response that acknowledges and attempts to understand individual’s suffering through emotional resonance. Compassion enhanced the key facets of empathy while adding distinct features of being motivated by love, the altruistic role of the responder, action, and small, supererogatory acts of kindness. Patients reported that unlike sympathy, empathy and compassion were beneficial, with compassion being the most preferred and impactful.

Conclusion:

Although sympathy, empathy, and compassion are used interchangeably and frequently conflated in healthcare literature, patients distinguish and experience them uniquely. Understanding patients’ perspectives is important and can guide practice, policy reform, and future research.

Keywords: Sympathy, empathy, compassion, advanced cancer, palliative care, grounded theory

What is already known about the topic?

Compassionate care is increasingly considered by patients, family members, and policymakers as a core dimension of quality care, particularly in palliative care.

Sympathy, empathy, and compassion are often used interchangeably within the healthcare literature despite some key notable differences.

What this paper adds?

While there have been studies investigating the constructs of sympathy, empathy, and compassion independently, to date no known studies have analyzed the three constructs using direct patient accounts.

The study identifies the key elements of each construct from the perspective of patients, including unique definitions.

While sympathy was considered largely unhelpful, empathy and compassion were received positively by patients, with most patients preferring compassion’s orientation toward action- and virtue-based motivators.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

Understanding patients’ perspectives on the similarities, differences, and preferences between sympathy, empathy, and compassion can guide patient-oriented research and optimize evidence-based, patient-centered care.

This study provides conceptual clarity for healthcare policy and system reform related to enhancing compassionate healthcare systems from the perspective of the individuals these systems serve.

Background

Healthcare today is paying a great deal of attention to patient-reported outcomes and person-centered care delivery.1,2 Clinicians, policymakers, patients, and their families are calling for healthcare providers to move beyond the delivery of services and to more explicitly consider the preferences, needs, and values of the persons receiving these services.3–6 Within this discussion, the constructs “empathy,” “sympathy,” and “compassion” are important principles within these models of care. But what exactly do these three constructs mean within the context of healthcare delivery? How should healthcare providers and researchers define, differentiate, and integrate them into practice? And, more importantly, how do patients understand and experience these constructs within the delivery of their healthcare? The aim of this study was to investigate advanced cancer patients’ perspectives, understandings, experiences, and preferences of “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “compassion” in order to develop conceptual clarity for future research and to inform clinical practice. Understanding the similarities and differences between these constructs can provide conceptual clarity in a field of research that often utilizes these terms interchangeably, thereby guiding healthcare policy and practice efforts to provide evidence-based, patient-centered care.

Sympathy, empathy, and compassion are closely related terms. They are often used interchangeably within healthcare policy, delivery, and research in describing some of the human qualities that patients desire in their healthcare providers.7–10 But what specifically do these terms mean, how are they related to one another, and what are patients’ perceptions and preferences toward each of them? A scoping review of the literature11 revealed that, while considerable scholarly activity has been conducted to distinguish between these constructs,12–16 there is a lack of empirical research informing this topic. While addressing this gap is important throughout all of healthcare, it is perhaps most important within palliative care, where relief of suffering and providing compassion in patients with advanced illness are explicit goals of care.17,18

Sympathy has been defined in the healthcare literature as an emotional reaction of pity toward the misfortune of another, especially those who are perceived as suffering unfairly.16,19 In contrast, empathy has been defined as an ability to understand and accurately acknowledge the feelings of another, leading to an attuned response from the observer.16,20,21 In general, researchers identify two types of empathy: cognitive empathy (detached acknowledgment and understanding of a distressing situation based on a sense of duty) and affective empathy, which while containing each of the elements of cognitive empathy, extends to an acknowledgment and understanding of a person’s situation by “feeling with” the person.16,22 Neurological studies have reported that witnessing a person in suffering activates neural pain pathways in the brain of the empathizer.22 Studies investigating empathy from the perspective of healthcare providers have identified a troubling trend—the erosion of empathy over the course of healthcare education and clinical practice.23–25

Etymologically, “compassion” means to “suffer with”26 and has been defined as “a deep awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it.”27 Our previously published grounded theory study of patient perspectives of compassion, defined compassion as “a virtuous response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person through relational understanding and action.”28 Compassion seems to differ from sympathy and empathy in its proactive approach, the selfless role of the responder, and its virtuous motivators aimed at ameliorating suffering. Gilbert and Choden29 discuss the relationship between these three constructs from a Buddhist perspective, conceptualizing sympathy as an emotional reaction, without conscious thought and reflection. Empathy is understood as a more complex interpersonal construct that involves awareness and intuition, while compassion is defined as “a way to develop the kindness, support, and encouragement to promote the courage we need—to take the actions we need—in order to promote the flourishing and well-being of ourselves and others” (p. 98). According to Way and Tracy,30 compassion is marked by the following three elements: recognizing suffering, relating to people in their suffering, and reacting to suffering. While there have been studies conducted on the nature of compassion from the perspective of healthcare providers, we could locate only two studies that included a patient cohort.31,32

What is certain in the healthcare literature and policy is that patients’ desire increased compassion within healthcare.33–38 Furthermore, research has indicated that compassion and empathetic care are ways of improving patient-reported outcomes and patient satisfaction.16 While there have been individual studies on sympathy, empathy, and compassion in a clinical setting, to date no studies have analyzed the three constructs using direct patient reports. To address that gap in the literature, we conducted a secondary analysis of data subset from a larger grounded theory study on the construct of compassion,28 which focused on palliative cancer patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences of the constructs of sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

Methods

Study population

Prior to developing the larger study protocol, the research team conducted a review of the literature which revealed a significant research gap related to the relationship between sympathy, empathy, and compassion. As a result of this review, the research team decided, at a protocol development meeting, to add additional questions to the interview guide in order to collect data and conduct a secondary analysis on this related field of inquiry (Box 1). The research protocol was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (E-24268). All participants provided signed informed consent to participate in the qualitative interviews, after receiving information on the study and after all participant questions were answered. Participants were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age, able to read and speak English, had a terminal cancer diagnosis and a life expectancy of less than 6 months, did not demonstrate evidence of cognitive impairment, and were able to provide written informed consent. Patients were excluded from the study if they were cognitively impaired or too ill to participate in the study as determined by their palliative care team. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were first informed of the study by a member of the palliative care team and if interested, were then contacted by a member of the research team.

Box 1.

Guiding interview questions.

| 1. What are the things that you have found to be important to your well-being during your illness? Particularly as it relates to the care you have received? 2. In terms of your own illness experience, what does compassion mean to you? 3. Can you give me an example of when you experienced care that was compassionate? 4. How do you know when a healthcare professional is being compassionate? 5. Since you have had cancer, has compassionate care always been helpful? Have been there times when health providers’ efforts to be compassionate missed the mark? 6. What advice would you give healthcare providers on being compassionate? (Do you think we can train people to be compassionate? If so, how)? 7. We have talked about compassion, another word that might be related to compassion is sympathy. In your experience are compassion and sympathy related? (Tell me how they are the same or different) 8. We have talked about compassion and sympathy, another word that might be related to compassion is empathy. In your experience are compassion and empathy related? (Tell me how they are the same or different) 9. How does what you have told me about compassion relate to your experience of spirituality? 10. Is there anything that that we have not talked about today that we have missed or you were hoping to talk about? |

Source: Sinclair et al.28

Participant recruitment occurred from May through December, 2013. Members of the palliative care team initially approached patients on an individual basis to gauge interest; a total of 151 patients were referred to the study nurse. Of those expressing initial interest, 25 were too ill to participate and were ineligible to participate. Among the 126 participants, 48 were not interested in participating, 5 were discharged, and 18 died prior to the scheduled interview. Two participants were not included in the results, as one was transferred to hospice before the interview could be completed, and the other was excluded due to audio recorder difficulties. A final sample of 53 patients was needed to obtain data saturation.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, individual interviews (Box 1) and a demographic questionnaire (Table 1). In order to mitigate interview bias and the Hawthorne effect, all interviews were conducted by an experienced research nurse and held in a private space within the hospital. The research nurse was employed by the Clinical Trials Research Unit of the host hospital and was neither a member of patients’ clinical care team nor participated in the data analysis. Interviews, averaging 1 h in length, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Table 1.

Demographic information (numbers expressed as percentages, unless otherwise stated).

| Mean age (years) | 61.44 |

| Men | 35.19 |

| Women | 64.81 |

| Mean (range) time between interview and death (days)a | 79.56 (8–261) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 3.70 |

| Married/common law/cohabiting | 70.37 |

| Divorced/separated | 16.67 |

| Widowed | 7.41 |

| Other | 1.85 |

| Person living withb | |

| Spouse/partner | 70.37 |

| Parent(s) | 3.70 |

| Sibling(s) | 1.85 |

| Child(ren) | 31.48 |

| Other relative(s) | 5.56 |

| Friend(s) | 1.85 |

| Other | 5.56 |

| Alone | 18.52 |

| Highest education level attained | |

| No formal education | 0.00 |

| Elementary—completed | 1.85 |

| Some high school | 16.67 |

| High school—completed | 9.26 |

| Some university/college/technical school | 20.37 |

| University/college/technical school—completed | 38.89 |

| Post-graduate university—completed | 12.96 |

| Employment statusb | |

| Retired | 59.26 |

| On sick leave | 5.56 |

| On disability | 31.48 |

| Working full-time | 1.85 |

| Working part-time | 5.56 |

| Household net income | |

| ≤CAD$60,000/year | 29.62 |

| >CAD$60,000/year | 70.38 |

| Religious and spiritual status | |

| Spiritual and religious | 53.70 |

| Spiritual but not religious | 37.04 |

| Religious but not spiritual | 3.70 |

| None | 5.56 |

Based on 45 patients who had died at the time of analysis.

The total for these categories exceeds 100% because patients were permitted to provide more than one response.

Data analysis

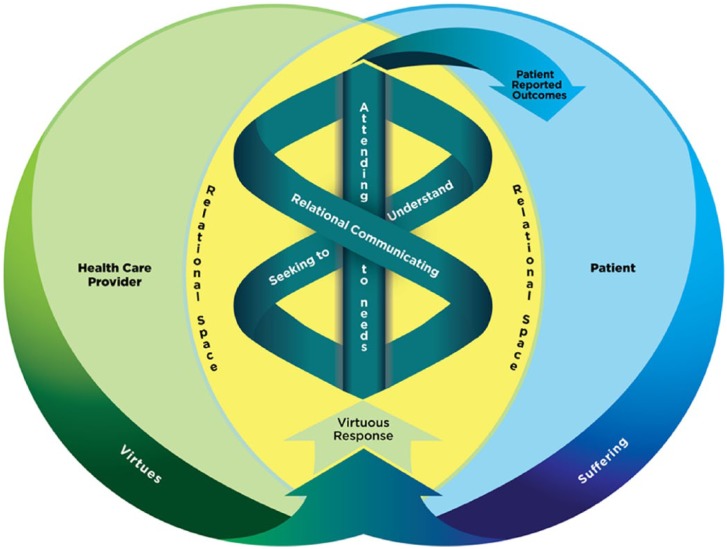

Interview data related to patients’ understandings of the constructs and relationship between sympathy, empathy, and compassion were analyzed in accordance with the three stages and principles of Straussian grounded theory (open, axial, and selective coding), using the constant comparative method,39,40 alongside data within a larger study aimed at conceptualizing, codifying, and constructing a patient-informed empirical model of compassion (Figure 1), described in detail elsewhere.28 Our original rationale for conducting a secondary analysis on the relationship between these three constructs was further validated in the analysis process, as our large qualitative sample (n = 53) generated considerable substantive data warranting a separate report which was beyond the scope of the compassion model.28 The three stages of Straussian grounded theory analysis generated codes, themes, and categories related to the constructs of interest which were further analyzed by members of the research team (S.S., T.H., S.M., S.R., and K.B.). The purpose of this secondary analysis was to gain conceptual clarity, codify the key elements of each construct, determine their relationship to one another, and identify the gaps leading which are outlined (Table 3) and illustrated (Figure 2). The reported results of this study were in accordance with and met each of the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)).

Figure 1.

The compassion model.

Reprinted from Sinclair et al.28

Table 3.

The relationship between sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

| Sympathy | Empathy | Compassion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | A pity-based response to a distressing situation that is characterized by a lack of relational understanding and the self-preservation of the observer | An affective response that acknowledges and attempts to understand an individual’s suffering through emotional resonance | A virtuous response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person through relational understanding and action |

| Defining characteristics | Observing Reacting Misguided Lack of understanding Unhelpful Ego based Self-preservation |

Acknowledgment of suffering Understanding the person Affective response |

Supererogatory Non-conditional Virtuous Altruistic Instrumental Action-oriented response |

| Response to suffering | Acknowledgment | Acknowledgment, understanding, and emotional resonance | Acknowledgment, understanding, and emotional resonance linked with action aimed at understanding the person and the amelioration of suffering |

| Type of response | A visceral reaction to a distressing situation | Objective and affective response to a distressing situation | A proactive and targeted response to a distressing situation |

| Emotional state of observer | Emotional dissonance | Emotional resonance and emotional contagion (“feeling with”) | Emotional engagement and resilience |

| Motivators of response | Pity/ego/obligation | Circumstantial/affective state of observer/duty/relatedness to patient/deservedness of patient | Virtues/dispositional |

| Relationship of observer to suffering | External | Proximal/isomorphic | Instrumental/relational/transmorphic |

| Intended outcomes | Self-preservation of observer | Objective and affective understanding of sufferer | Amelioration of multifactorial suffering |

| Patient-reported outcomes | Demoralized Patronized Overwhelmed Compounded suffering |

Heard Understood Validated |

Relief of suffering Enhanced sense of well-being Enhanced quality of caregiving |

| Examples | “I’m so sorry” “This must be awful” “I can’t imagine what it must be like” |

“Help me to understand your situation” “I get the sense that you are feeling …” “I feel your sadness” |

“I know you are suffering, but there are things I can do to help it be better?” “What can I do to improve your situation?” |

Figure 2.

Sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

Results

After the data had been coded and analyzed, the three constructs of sympathy, empathy and compassion generated several themes (Table 2). While patients distinguished and preferred compassion to empathy, they also identified overlapping features. In contrast, patients identified sympathy as a largely distinct and unhelpful construct based on pity and a lack of understanding (Table 3).

Table 2.

Major categories and themes.

| Categories | Themes |

|---|---|

| Sympathy | An unwanted pity-based response |

| A shallow and superficial emotion based on self-preservation | |

| An unhelpful and misguided reaction to suffering | |

| Empathy | Engaging suffering |

| Connecting to and understanding the person | |

| Emotional resonance: putting yourself in the patient’s shoes | |

| Compassion | Motivated by love |

| The altruistic role of the responder | |

| Action oriented | |

| Small supererogatory acts of kindness |

Sympathy

Most participants described sympathy as an unwanted and misguided pity-based response that was easily given and seemed to focus more on alleviating the observer’s distress toward patient suffering, rather than the distress of the patient. After comparing and contrasting individual patient responses, the following definition of sympathy emerged: a pity-based response to a distressing situation that is characterized by a lack of relational understanding and the self-preservation of the observer.

An unwanted pity-based response

Participants repeatedly described sympathy as a pity-based response that was unwelcomed and in some incidences despised by patients. Patients acknowledged that expressions of sympathy could be well-intended on the part of acquaintances and healthcare providers. Ultimately, however, they were experienced as being misguided and, ironically, had a largely detrimental effect on patient well-being. Specifically, patients felt that sympathy left them feeling demoralized, depressed, and feeling sorry for themselves:

I do not want sympathy in any way, shape or form … I don’t have any room to rent out to that space and I’ve said it many, many times to those who come and visit me and those who want to come and visit me. Don’t come and look like this is going to be the last time you’re going to see me because it’s not. To feel sorry for me … that is wasted energy. (Patient 5)

I prefer, you know, compassion is okay, but sympathy, I’m not really fond of because it might put me into a feeling sorry for myself mode. … too much sympathy, you don’t want that because that doesn’t boost you so I think compassion is, and empathy and compassion are the important things, but I find it’s got me down if anybody is too sympathetic, you know, it makes you cry, (Patient 4)

A shallow and superficial emotion based on self-preservation

In comparing sympathy, empathy, and compassion, participants agreed that sympathy was the easiest of the three responses for observers to give away. Participants felt this was due largely to sympathy being a shallow and superficial emotion that was typically exhibited by individuals who wished to remain distant from the patient’s situation. While sympathy often involved thoughtful words or gestures, it was described by patients as disingenuous, depersonalized, and emotionally distant and detached from the person in suffering. Many participants expressed that the detached nature of sympathy was a visceral reaction that was primarily concerned about the self-preservation of the observer, rather than an attempt to understand the person in need or a desire to alleviate suffering:

Sympathy is very easy, it’s an emotion, probably one of the easiest emotions to fake. I hate sympathy! (Patient 40)

If you’re thinking of looking for sympathy, you’ll find it between shit and syphilis in the dictionary. (Patient 34)

I hate sympathy, it feels shallow, it feels like, “Oh I’m so sorry you’re going through this,” and it doesn’t feel genuine to me. (Patient 7)

An unhelpful and misguided reaction to suffering

Patients’ dislike of sympathy was not merely due to its pity-based motivators and associated superficial responses but its lack of utility in relieving patient suffering. Although participants felt that sympathy was rooted in emotional distancing, it was not necessarily a passive state as it could equally invoke a demonstrative reaction on the part of the responder, leaving patients feeling overwhelmed by sympathetic phone calls, a flood of get-well cards, and other emotionally laden, energetic expressions of concern by others. Unlike empathy, and especially compassion, sympathy was short-lived and dissipated shortly after its initial expression. Participants experienced sympathy as not understanding their own individualized needs, but rather as a reaction intended to serve the needs of the observer. Therefore, it ultimately was not meaningful and was ineffective in meeting patient needs:

Sympathy is, it’s like flattery, it sounds pretty but it goes nowhere and it does nothing. (Patient 51)

Sympathy, I think is you’re feeling sorry for that person. I don’t want somebody to feel sorry for me, I want you to help me. (Patient 48)

When I was first diagnosed. I got all kinds of sympathy cards, you know well wishes from people, and you know people phoning that you haven’t heard from for years and things like that. That’s sympathy … because you know they phone you know, wish you well and I haven’t heard from them since. (Patient 13)

Empathy

Patients had a much more positive response to empathy than to sympathy. They described empathy as a more emotionally engaged process, whereby individuals attempted to attune to the emotions of the patient through acknowledgment of suffering. Patients experienced this as a warm, gentle attempt to understand their emotional state. Whereas patients described sympathy as a self-motivated, emotional reaction to someone else’s suffering based on a lack of understanding of the person’s needs, empathy was an affective response that acknowledges and attempts to understand an individual’s suffering through emotional resonance.

Engaging suffering

An essential and distinguishing feature of empathy was the proximity of the responder in relation to the suffering of the patient. Unlike sympathy, which involved individuals emotionally distancing themselves from suffering by avoidance or by an overly demonstrative and misguided reaction, empathy required the individual to approach the patient’s suffering, in a vulnerable manner:

Empathy enters into another’s suffering … it’s just the ability to be there. (Patient 8)

Connecting to and understanding the person

Patients identified empathetic individuals as not only engaging suffering but also personally connecting to patients, in ways that sympathetic individuals were incapable or unwilling to do. What was deficient in sympathy but intrinsic to empathy was the notion of understanding. According to patients, a personal connection allowed the empathizer to develop a deeper understanding of the person and their individualized suffering, thereby allowing the empathizer to address patient issues in a more effective and personalized manner:

That’s because empathy is, for me, empathy is that personal connection … whereas sympathy doesn’t have to be personalized, it can be, it can just be, you know it’s just all those comments, my thoughts are with you, blah, blah, blah, all that kind of stuff, but empathy is where you’re actually connecting with the person. (Patient 46)

… I think empathy is the ability to be able to communicate on a visual, physical whatever level with the other individual and sort of make a connection with them … but there’s also sort of a deeper understanding of the situation and this sort of thing. (Patient 49)

Emotional resonance: putting yourself in the patient’s shoes

The metaphor of individuals “putting themselves in the patient’s shoes” was frequently used by patients in describing empathy. This metaphor speaks to healthcare providers’ ability to emotionally relate to what their patient is feeling—to engage suffering by way of understanding and being able to relate on an affective level:

… empathy is, yeah, like stepping inside somebody else’s shoes and, you know, trying to see what it’s like without actually being there … being able to slip and slide in somebody else’s shoes and trying to understand from their standpoint what it means to be going through this. (Patient 5)

Empathy is where you put yourself in the person’s shoes, and you try to imagine yourself walking in those shoes, and how you personally would react. (Patient 19)

When you empathize with people you, you’ve crawled right into their moccasins. (Patient 44)

Compassion

Compassion was identified as the preferred care medium by patients, enhancing the key aspects of engaging suffering, understanding the person and emotional resonance contained within empathy, while adding defining qualities of being motivated by love, the altruistic role of the responder, action, and small but supererogatory acts of kindness. The definition of compassion that emerged from the data was a virtuous response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person through relational understanding and action.

Motivated by love

Patients recognized compassion as an affective response to suffering, motivated within the virtues of the individual responders. While patients identified virtues such as kindness, genuineness, and honesty as the sources of a compassionate response, love was the most frequently cited virtue distinguishing compassion from sympathy and empathy. Patients described compassionate love as non-conditional, independent of patient behavior, relatedness, and deservedness, and not being contingent on the responder’s own emotional state during the clinical encounter:

Compassion I think means to me, giving me love, giving me love, unconditional. (Patient 45)

I think you can tell those that are there for the paycheque, or those that are there because they love what they do and they love the patients. (Patient 26)

I think it’s all about love, not getting, you know, like not getting hung up on what the big picture is, it’s about the now and ensuring that that person has been given that chance to be in the now. (Patient 6)

The altruistic role of the responder

A related theme that emerged prominently from the interview data was the ability of compassionate responders to put aside their needs to meet the needs of the patient. Whereas sympathy involved a focus on the needs of the observer and empathy involved responders being attuned to the needs of the patient, compassion involved responders using themselves as an instrument in the relief of suffering. Patients felt that the selfless role of compassionate individuals had an enduring impact as their care extended beyond the clinical interaction and their professional role to a long-term commitment to the patient:

… I think I’ve come across a lot of people who have been very, very compassionate in understanding where I’m coming from, in accepting who and what my decisions are without, sort of, throwing their own feelings and empathy into this situation, they’re thinking about me. (Patient 5)

It’s being tender, it’s being aware of someone’s needs before yourself. (Patient 11)

Action oriented

Compassion, in contrast to both sympathy and empathy, was described by participants as action oriented, aimed at ameliorating suffering. While both compassion and empathy acknowledge and attempt to understand the needs of a person in suffering, empathy was solely a responsive state, while compassion added a proactive element that aimed to augment shared suffering with action—feeling for and doing for. In contrast to empathy where emotional resonance is an end point, emotional resonance in relation to compassion was a catalyst to a deeper emotional and physical response that aimed to improve the situation:

Compassion is actions … sympathy are thoughts and well wishes. (Patient 14)

I think empathy is more of a feeling thing where you’re aware of somebody’s suffering, and compassion is when you act on that knowledge. (Patient 23)

Sympathy are words and you know, “jeez I hope you feel better” and “it’s terrible you got this” and compassion is running over and getting a barf bag. (Patient 13)

Small supererogatory acts of kindness

Whereas sympathy was often expressed demonstratively, whether through grandiose gestures of care or over-expressions of emotion, compassion was often conveyed by subtle acts of kindness that often fell outside of routine care. Patients described these supererogatory acts in metaphorical language of “going above and beyond” or “going the extra mile.” It was in small acts of kindness, particularly acts that were not duty based, non-remunerated, and not part of the job description, where patients felt that the true intentions and nature of their healthcare provider was made plainly evident. The impact that patients ascribed to these small supererogatory acts was immense—it relieved their suffering, enhanced their sense of well-being, and positively influenced their perceptions of the quality of care they received from their healthcare providers:

Well because they put themselves out, they’re doing it uh that extra little bit that you don’t normally get. (Patient 36)

Just going that extra mile. It’s just a feeling. It’s hard to explain … that extra smile, that extra you know, “hi how are you?” Hand on your shoulder, you know, we’re here for you. (Patient 50)

Putting your arm around the shoulder and just letting them know that, “I’m here,” be it big or little, it doesn’t matter … (Patient 5)

Discussion

Patients living with an incurable illness are uniquely positioned to provide insights into the constructs of compassion, empathy, and sympathy (Table 3). They often have extensive experience with the healthcare system and in their most vulnerable moments, are in the hands of, and at the mercy of, a healthcare system and its ability to respond to their suffering.

Sympathy

In this study, patients distinguished between the constructs of “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “compassion” (Table 3 and Figure 2). While patients acknowledged considerable overlap between empathy and compassion, they were unequivocal in identifying sympathy as a distinct and unhelpful reaction to patients’ suffering. Sympathy was described as a superficial acknowledgment of suffering, invoking a pity-based response that failed to sufficiently acknowledge the person who was suffering. Hence, sympathy appears to be a coping strategy that individuals invoke when exposed to situational suffering that they feel unable or inadequate to address.

Empathy

In contrast, empathy and compassion were welcomed and valued by patients. Patients felt that empathy and compassion share attributes of acknowledging, understanding, and resonating emotionally with a person who is suffering. Compassion also added distinct features: action, supererogatory acts, virtuous motivators, and unconditional love, with compassionate responders functioning in an instrumental fashion in the amelioration of suffering (Table 3 and Figure 2). These results are consistent with studies focused on healthcare providers’ conceptualizations of compassion as an intensification of both cognitive and affective empathy coupled with the addition of action30,41 aimed at the alleviation of suffering.16,30,41

Compassion

Neuroplasticity research is beginning to offer important insights on the human experiences of empathy and compassion. One study found differences in brain activation in participants who engaged in contemplative exercises focused on enhancing empathy (resonating with another person’s suffering) compared to participants who meditated on compassionate thoughts (extending caring feelings to others).42 Whereas conjuring empathic thoughts produced a negative effect in participants activating regions of the brain associated with aversion, compassionate feelings produced a positive effect, activating regions of the brain associated with reward, love, and affiliation. Taken together, these findings suggest that compassion may not only be better for patients but also for their healthcare providers, requiring a reconceptualization of the notion of compassion fatigue as empathetic distress.42,43

Motivators and antecedents

From the perspective of patients, compassion, sympathy, and empathy had distinct motivators (Table 3). Patients perceived sympathy as being motivated by pity, ego, and obligation, leading to an avoidant or over-reactive response. Empathy was motivated by the affective state of the healthcare provider toward the patient and a sense of duty. Compassion differed from empathy, finding its motivation in the inherent virtues of individuals, particularly unconditional love, generating a virtuous response and culminating in action aimed at the amelioration of suffering.28 The virtue-based motivators of compassion mean that relative to empathy, compassion is less dependent on a sense of duty, less dependent on the emotional state of the observer, and, as has been confirmed by other studies, is less influenced by the perceived relatedness and deservedness of the patient.28,44–46 In contrast, although patients felt that compassion engendered relationship, they did not feel it was contingent on relationship, but rather the unconditional acceptance of the patient, even when the patient was at their worse.28,30,47

Implications and limitations

Results of this study shed light on different responses healthcare providers may manifest in response to suffering (Table 3 and Figure 2). While participants believed that sympathy positioned individuals as “outsiders” in the clinical encounter, compassion and empathy placed the responders in a more vulnerable position alongside (empathy) and within suffering (compassion). Patient accounts of this important difference often used metaphorical language related to responders putting themselves in the patient’s shoes—to situate themselves in close proximity to suffering. In addition to this notion of orienting to the patients’ perspective, a number of patients expanded this metaphor in reference to compassion, which they felt also involved “walking a mile in a person’s shoes,” implying a long-standing commitment to the patient over time, regardless of the actual or anticipated duration of the clinical relationship. A final difference related to the role of compassionate carers was the altruistic and instrumental functions they played in ameliorating suffering. These findings align with other studies that reported that compassionate individuals used self-effacement to meet the needs of another person,48,49 often through small, yet impactful supererogatory acts.8,31,50 These results highlight the importance of research that examines healthcare providers’ perspectives and experiences, including how their responses to suffering might impact their personal and professional lives.

Our study comparing and contrasting patients’ experiences of sympathy, empathy, and compassion addresses an important gap in the literature. One of the most compelling findings of this study is how patients distinguish and prefer compassion. Although patients appreciated empathy, they also noted a number of limitations, namely, that it is not linked to action, is conditional, and does not involve supererogatory acts. These results are consistent with neuroplasticity research that reported that empathy activates neural networks that are isomorphic (mirroring) to the emotional state of the sufferer.22 As a result, the authors postulate that empathy has a potential dark side, whereby it can be used to find a weakness to make a person suffer or can cause empathetic distress and burnout on the part of the caregiver.42,51 While participants in our study did not identify an adverse effect of empathy, they did note some provocative differences related to the role of emotional resonance in each of these constructs. In contrast to empathy where emotional resonance seemed to function as an end point, in relation to compassion, emotional resonance was coupled with an intention to transform suffering, requiring the responder to move from “feeling with” (empathy) to “feeling for” the patient—a distinguishing feature of compassion identified by others. Finally, in terms of study limitations, as this was a qualitative study, generalizability is limited, and as 72% of our sample had at least some university education, this may have resulted in an overly intellectualized understanding of these three constructs.52

Conclusion

This study reports on palliative cancer patients’ experiences of sympathy, empathy, and compassion, including differences and their preferences between them. While these three constructs tend to be used interchangeably within the healthcare literature, there are marked differences according to the individuals who are the main recipients of these care constructs—patients. In contrast to sympathy, patients reported both empathy and compassion as having a positive effect on their care experiences, allowing them to feel heard, understood, and validated. In addition to these patient outcomes, compassion was distinguished by its orientation toward action, its foundation in unconditional love, its expression through small supererogatory acts, and the altruistic role that compassionate carers played in this process. Deconstructing these terms can inform future research comparing these three constructs on patient quality of life, family member grief, and healthcare provider job satisfaction. Additionally, it provides a conceptual framework for the development of targeted educational interventions that acknowledge individual variance in expressions (trainees) and receptivity (patients) of compassion.53 Ultimately, this research can inform evidence-based clinical practice to enhance this vital, but previously ill-defined dimension of healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Barb Gawley, research nurse, for her dedication and commitment to this study. They would also like to acknowledge and thank the research participants who were compelled to join this research study, despite time being precious.

Footnotes

Declaration of a conflict of interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Open Operating Grant (grant number 125931).

References

- 1. Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, et al. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff 2010; 29: 1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Attree M. Patients’ and relatives’ experiences and perspectives of “Good” and “Not So Good” quality care. J Adv Nurs 2001; 33: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Medical Association. Code of medical ethics: principle 1. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, et al. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad Med 2013; 88: 1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paterson R. Can we mandate compassion? Hastings Cent Rep 2011; 41: 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationary Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crowther J, Wilson KC, Horton S, et al. Compassion in healthcare—lessons from a qualitative study of the end of life care of people with dementia. J R Soc Med 2013; 106: 492–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. Defining priorities for improving end-of-life care in Canada. CMAJ 2010; 182: E747–E752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Institute of Medicine. Improving medical education: enhancing the behavioral and social science content of medical school curricula. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sinclair S, Norris J, McConnell S, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gelhaus P. The desired moral attitude of the physician: (II) compassion. Med Health Care Philos 2012; 15: 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Entwistle F. Give support, not sympathy. Nurs Times 2014; 110: 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graber DR, Mitcham MD. Compassionate clinicians: take patient care beyond the ordinary. Holist Nurs Pract 2004; 18: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lelorain S, Bredart A, Dolbeault S, et al. How does a physician’s accurate understanding of a cancer patient’s unmet needs contribute to patient perception of physician empathy? Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98: 734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Post SG, Ng LE, Fischel JE, et al. Routine, empathic and compassionate patient care: definitions, development, obstacles, education and beneficiaries. J Eval Clin Pract 2014; 20: 872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Hospice and Palliative Care Association. Definition of palliative care. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Hospice and Palliative Care Association, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soanes C, Stevenson A. Sympathy. In: Stevenson A. (ed.) Oxford English dictionary of English. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52: S9–S12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soanes C, Stevenson A. Empathy. In: Stevenson A.(ed.) Oxford English dictionary of English. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hein G, Singer T. I feel how you feel but not always: the empathic brain and its modulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008; 18: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med 2009; 84: 1182–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kane GC, Gotto JL, Mangione S, et al. Jefferson Scale of Patient’s Perceptions of Physician Empathy: preliminary psychometric data. Croat Med J 2007; 48: 81–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neumann M, Edelhauser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med 2011; 86: 996–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoad T. Concise Oxford dictionary of English etymology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nunberg G, Newman E. The American heritage dictionary of the English language. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sinclair S, McClement S, Raffin Bouchal S, et al. Compassion in health care: an empirical model. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 51: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilbert P, Choden Mindful compassion: using the power of mindfulness and compassion to transform our lives. Little: Brown Book Group, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Way D, Tracy SJ. Conceptualizing compassion as recognizing, relating and (re)acting: a qualitative study of compassionate communication at hospice. Commun Monogr 2012; 79: 292–315. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bramley L, Matiti M. How does it really feel to be in my shoes? Patients’ experiences of compassion within nursing care and their perceptions of developing compassionate nurses. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23: 2790–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van der Cingel M. Compassion in care: a qualitative study of older people with a chronic disease and nurses. Nurs Ethics 2011; 18: 672–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, et al. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roter DL, Hall JA, Katz NR. Relations between physicians’ behaviors and analogue patients’ satisfaction, recall, and impressions. Med Care 1987; 25: 437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sinclair S, Raffin Bouchal SR, Chochinov H, Hagen N, et al. Spiritual care: how to do it. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012; 2: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 1484–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Riggs JS, Woodby LL, Burgio KL, et al. “Don’t get weak in your compassion”: bereaved next of kin’s suggestions for improving end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006; 174: 627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown B, Crawford P, Gilbert P, et al. Practical compassions: repertoires of practice and compassion talk in acute mental healthcare. Sociol Health Ill 2014; 36: 383–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol 2014; 24: R875–R878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klimecki OM, Singer T. Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In: Oakley B, Knafo A, Madhavan G. (eds) Pathological altruism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 368–383. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eisenberg N, Miller PA. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol Bull 1987; 101: 91–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cialdini RB, Brown SL, Lewis BP, et al. Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: when one into one equals oneness. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997; 73: 481–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rudolph U, Roesch S, Greitemeyer T, et al. A meta-analytic review of help giving and aggression from an attributional perspective: contributions to a general theory of motivation. Cognit Emot 2004; 18: 815–848. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vivino BL, Thompson BJ, Hill CE, et al. Compassion in psychotherapy: the perspective of therapists nominated as compassionate. Psychother Res 2009; 19: 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gilbert P. Compassion: conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. East Sussex: Routledge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull 2010; 136: 351–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burnell L. Compassionate care: a concept analysis. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2009; 42: 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Ricard M, et al. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2014; 9: 873–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Halifax J. Understanding and cultivating compassion in clinical settings. The A.B.I.D.E. compassion model. In: Singer T, Bolz M. (eds) Compassion: bridging practice and science. Munich: Max Planck Society, 2013, pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sinclair S, Torres M, Raffin Bouchal S, et al. Compassion training in healthcare: what are patients’ perspectives on training healthcare providers? BMC Medical Education 2016; 16: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]