Abstract

Background:

Patients with advanced conditions may present a wish to hasten death. Assessing this wish is complex due to the nature of the phenomenon and the difficulty of conceptualising it.

Aim:

To identify and analyse existing instruments for assessing the wish to hasten death and to rate their reported psychometric properties.

Design:

Systematic review based on PRISMA guidelines. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments checklist was used to evaluate the methodological quality of validation studies and the measurement properties of the instrument described.

Data sources:

The CINAHL, PsycINFO, Pubmed and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to November 2015.

Results:

A total of 50 articles involving assessment of the wish to hasten death were included. Eight concerned instrument validation and were evaluated using COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments criteria. They reported data for between two and seven measurement properties, with ratings between fair and excellent. Of the seven instruments identified, the Desire for Death Rating Scale or the Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death feature in 48 of the 50 articles. The Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death is the most widely used and is the instrument whose psychometric properties have been most often analysed. Versions of the Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death are available in five languages other than the original English.

Conclusion:

This systematic review has analysed existing instruments for assessing the wish to hasten death. It has also explored the methodological quality of studies that have examined the measurement properties of these instruments and offers ratings of the reported properties. These results will be useful to clinicians and researchers with an interest in a phenomenon of considerable relevance to advanced patients.

Keywords: Wish to hasten death, assessment instrument, tool, advanced illness, psychometric properties, systematic review, palliative care, desire to die

What is already known about the topic?

Patients with advanced disease may present a wish to hasten death (WTHD) as a reaction to suffering.

Data for the prevalence of a WTHD show considerable variability (between 1.5% and 38%).

This wide variability may reflect not only a diversity of patient populations but also differences in the construct assessed, as well as in other aspects related to the characteristics of the instruments used.

What this paper adds?

We identified seven different instruments (five plus two modifications) that have been used to assess the WTHD in adults with advanced disease. However, not all of them have been subject to an analysis of their validity and reliability.

The Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death (SAHD) and the Desire for Death Rating Scale (DDRS), with its modifications, are the most widely used instruments, although in both cases limited information is available regarding their measurement properties.

The DDRS can readily be used in clinical practice, whereas the characteristics of the SAHD, especially its length and direct wording of items, may mean it is more suited to research.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

This study may help clinicians and researchers to choose the tool for assessing the WTHD that is best suited to their goals.

More studies are needed to examine the unknown measurement properties of the two most widely used instruments.

An understanding of how the different instruments have been used, as well as of the construct of the WTHD on which each one is based, is crucial when it comes to deciding which instrument to use in a given context.

Gathering patients’ own views about how they would like clinicians to explore this issue could help in developing an instrument that is better suited to the needs of patients.

Introduction

The wish to hasten death (WTHD) in the context of advanced disease is a complex phenomenon of growing interest among clinicians and researchers. Research to date has focused particularly on the multiple factors that may trigger such a wish,1–3 and recent studies4,5 suggest that in advanced patients it emerges as a reaction to suffering. Hence, a WTHD in these patients might be regarded as a red flag for suffering.

The estimated prevalence of the WTHD in patients with advanced disease varies considerably across studies, ranging between 1.5% and 37.8%.1,6–16 This variability in the published data is likely due to the characteristics of the patient samples studied, as well as to the assessment instruments used. Thus, the highest prevalence rates usually correspond to samples of patients in the advanced or terminal stage of disease,1,11,16–18 whereas the lowest rates have been reported in outpatients at various stages of disease or in active treatment.7,12,13 Prevalence rates also vary across studies that have used the same assessment instrument in apparently similar samples, due to the application of different cut-offs for the total score obtained on the instrument.11,19 At all events, comparison of results is hindered mainly by the fact that they are derived from different instruments and often without an explicit theoretical framework in which the concept of the WTHD is clearly defined.

Various methods typically associated with the reporting of health-related patient-reported outcomes (e.g. interviews, schedules, scales and questionnaires, hereafter referred to as ‘instruments’) have been used to assess the WTHD.1,9,20–23 Two of the most widely used among these instruments are the Desire for Death Rating Scale (DDRS)20 and the Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death (SAHD).21 The DDRS was designed in Canada to assess the WTHD among patients with cancer,20 and it has subsequently been used in several studies. The SAHD was developed in the United States and was initially applied towards the end of the 1990s in patients with HIV/AIDS21 and cancer.24 It has since become the most widely used instrument in the field and has been translated and validated in several languages.13,15,25–27

To date, no published study has analysed the different instruments used to assess the WTHD in patients with advanced disease. Consequently, this systematic review aims (a) to identify and analyse the studies that have assessed the WTHD in adult patients with advanced disease, (b) to analyse the characteristics of the different measurement instruments used for this purpose, (c) to evaluate the methodological quality of validation studies that have examined the psychometric properties of instruments for measuring the WTHD and (d) to rate the different instruments according to their reported psychometric properties.

Method

Design and data sources

This systematic review and analysis of instruments used to measure the WTHD was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.28 The search strategy was applied to the CINAHL, PsycINFO, Pubmed and Web of Science databases, from their inception to November 2015.

Eligibility criteria

Potential articles were selected by applying the following inclusion criteria: (a) peer-reviewed articles published in English, French or Spanish and (b) articles that mentioned the use of at least one instrument for measuring the WTHD in adult patients with advanced disease and/or who were being cared for in any palliative care facility. There were no restrictions in terms of study design or the type of measurement instrument used to assess the WTHD, since the aim of the review was to identify all the instruments that have been used to date; thus, we included not only instruments or questionnaires designed specifically for this purpose but also other forms of assessment that, among other aspects, sought to evaluate the WTHD. For this review, we excluded studies conducted with a paediatric population or in older people without advanced disease.

Search strategy and article selection

The search strategy used a combination of MeSH and free text terms covering three domains: WTHD, measurements and population. Table 1 shows the strategy that was finally used. This strategy was adapted to each of the databases.

Table 1.

Final database search strategy.

| #1 | ‘wish to die’ [Text Word] | Wish to hasten death |

| #2 | ‘wish to hasten death’ [Text Word] | |

| #3 | ‘wish for hastening death’ [Text Word] | |

| #4 | ‘desire to die’ [Text Word] | |

| #5 | ‘desire for early death’ [Text Word] | |

| #6 | ‘want to die’ [Text Word] | |

| #7 | ‘desire for death’ [Text Word] | |

| #8 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 | |

| #9 | ‘tool’ [Text Word] | Measurements |

| #10 | ‘instrument’ [Text Word] | |

| #11 | ‘scale’ [Text Word] | |

| #12 | ‘validation’ [Text Word] | |

| #13 | ‘measuring’ [Text Word] | |

| #14 | ‘evaluation’ [Text Word] | |

| #15 | ‘validation’ [Text Word] | |

| #16 | ‘assessment’ [Text Word] | |

| #17 | #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 | |

| #18 | ‘advanced illness’ [Text Word] | Population |

| #19 | ‘palliative care’ [MeSH] | |

| #20 | ‘cancer’ [Text Word] | |

| #21 | ‘chronic illness’ [Text Word] | |

| #22 | ‘terminally ill’ [MeSH] | |

| #23 | #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 | |

| #24 | #8 AND #18 AND #23 |

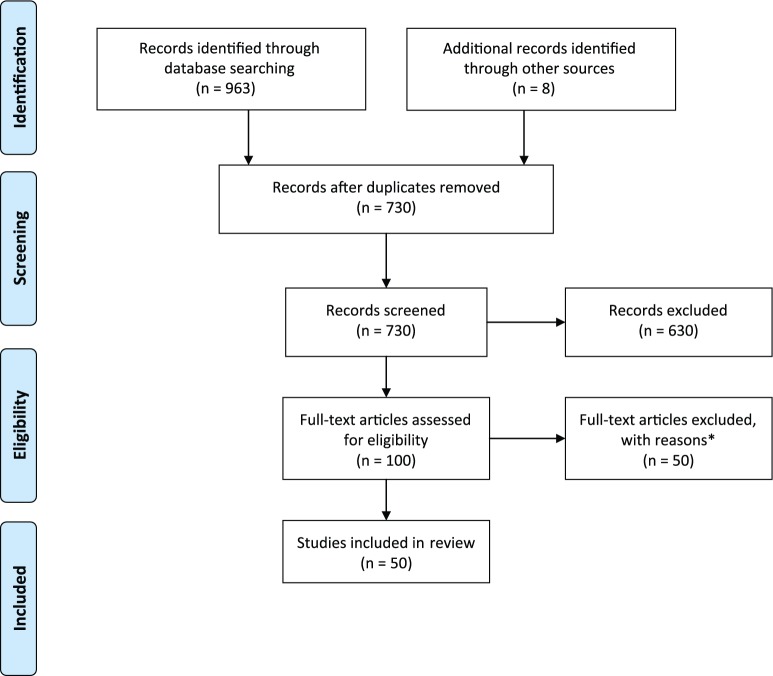

The search results were imported into a reference management software package, at which stage any duplicates were removed. The first author (M.B.-P.) independently selected potential articles, with the selection being verified by another researcher (C.M.-R.), who is an experienced systematic reviewer. The retrieved citations were sifted in three stages, first by title, second by abstract and finally by full text. Studies were omitted if they did not meet the inclusion criteria, with any disagreements being resolved by discussion between all researchers. Figure 1 illustrates the search process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

*Reasons for exclusion: (a) language of the publication (n = 1), (b) not peer-reviewed journal (n = 8), (c) the study did not include any WTHD measurement (n = 36), (d) the study is focused on the paediatric population (n = 1), (e) the target population is not advanced disease or palliative care (n = 3) and (f) measurement of the WTHD was based on the report of informants such as relatives or health professionals (n = 1).

Data extraction

Two researchers (M.B.-P. and C.M.-R.) used data extraction sheets to extract data from the studies included in the review and then analysed and compared these data.29 Once again, any disagreements were resolved by consensus among all the researchers. The following descriptive data were extracted: authors, year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, instrument used to measure the WTHD and the aim(s) of the study. The following study characteristics were also extracted: design, mean and standard deviation reported for the WTHD, setting and population.

Quality assessment

Two assessments of quality were performed, one for the methodological quality of studies reporting the measurement properties of specific instruments and another to rate the reported psychometric properties of the instruments used.

The first of these assessments applied the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist.30 The COSMIN checklist categorises the information provided by a study into 12 boxes, 9 of which contain standards for how each measurement property should be assessed (internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness). Each box contains between 5 and 18 items, with each item being scored on a 4-point rating scale (poor to excellent).31

As regards the second assessment, the quality of an instrument’s psychometric properties was evaluated using the criteria proposed by Terwee et al.,32 which enable each measurement property to be rated as positive (+), negative (−), indeterminate (?) or no information available (0).

In order to ensure consistency in the application of COSMIN criteria for evaluating studies31 and instruments,32 two researchers (M.B.-P. and C.M.-R.) applied the criteria independently. Any disagreements were then resolved through team discussion.

Data analysis and synthesis of results

For the extraction and analysis of data from the studies included, we created a spreadsheet in which the information was categorised according to the content and evaluation of the instruments used to measure the WTHD. The characteristics of the studies, as well as the evaluation of methodological quality and the quality rating of psychometric properties, were analysed and summarised in the form of a narrative summary.

Results

After application of the aforementioned inclusion criteria, a total of 50 articles were included in the review (see Figure 1, which also describes the main reasons for exclusion of records). No study was eliminated on the basis of quality criteria.

Characteristics of the included articles

Table 2 shows the main characteristics of the 50 articles included. They were all published in the last 20 years, with an even spread across the two decades. The largest proportion of studies, 34% of the total (n = 17), were carried out in the United States, followed by 16% in Canada (n = 8), 16% in Greece (n = 8) and 10% in Australia (n = 5).

Table 2.

Descriptive data for the included articles.

| Year, first author, country | Instrument | Study design | Population | Setting | Sample (final) | Percentage of total patient population that was eligiblea | Percentage of eligibleb participants included | Mean score for WTHD ± SD [range scored] | Cut-off used by authors (percentage of high WTHD according to cut-off) | Purpose of measuring the WTHD in the article included in the review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995, Chochinov,20 Canada | DDRS | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 200 | 23.0% | 92.6% | Not reported | ⩾4 (8.5%) | MP |

| 1999, Rosenfeld,21 USA | SAHD DDRS (both instruments in only 47 patients) |

Cross-sectional | HIV/AIDS patients | Home care; palliative care hospice | n = 195 | Not reported | Not reported | 3.05 ± 3.80 1.19 ± 1.65 |

⩾7 (12%) ⩾11 (6%) ⩾3 (15%) |

VAL |

| 2000,c Breitbart,6 USA | SAHD | Prospective | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 92 | 22% | 59.7% | 4.76 ± 4.3 [0–16] |

⩾10 (17%) | MP |

| 2000, Rabkin,48 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | ALS patients | ALS centre | n = 56 patients and 31 caregivers | Not reported | Not reported | 3.7 ± 3.4 | Not reported | OUT |

| 2000,c Rosenfeld,24 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 92 | Not reported | 59.7% | 4.76 ± 4.3 | ⩾10 (16.3%) | VAL |

| 2002, Chochinov,37 Canada | DDRS | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 213 | Not reported | 57.7% | 0.54 ± 0.81 (patients with intact sense of dignity) 1.3 ± 1.3 (patients with fractured sense of dignity) |

Not reported | OUT |

| 2002, Kelly,1 Australia | Modified DDRS | Mixed methods: qualitative and cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Hospice and home palliative care | n = 72 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ⩾5 (22.2%) | MP/VAL |

| 2002, Tiernan,22 Ireland | Four items designed by authors | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Hospice | n = 142 | 50.3% | Not reported | Not reported | Score 2 or 3 on any question (1.4%) | MP |

| 2003, Jones,7 Canada | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Cancer patients | Cancer centre | n = 224 | 60.2% | 77% | Not reported | ⩾10 (2%) | MP |

| 2003, Kelly,43 Australia | Modified DDRS | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care service | n = 256 | 19.3% | 49% | Not reported | ⩾5 (14%) | MP |

| 2003, Kelly,44 Australia | Modified DDRS | Mixed methods | Doctors and terminally ill cancer patient pairs | Hospice unit | n = 24 | Not reported | 62% | Not reported | ⩾5 (25%) | MP |

| 2003, McClain,49 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care hospital | n = 160 | 4.9% | 26.5% | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2003,c Pessin,8 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced AIDS patients | Long-term care treatment facility | n = 128 | 68.4% | Not reported | 2.8 ± 3.0 | ⩾7 (10%) | MP |

| 2004,c Kelly,45 Australia | Modified DDRS | Cross-sectional | Doctors and terminally ill cancer patient pairs | Palliative care service | n = 252 | 58% | 58% | Not reported | ⩾5 (14%) | MP |

| 2004, Kissane,62 Australia | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care or psycho-oncology clinics | n = 100 | Not reported | 61.3% | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2004, McClain,50 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care hospital | n = 276 | Not reported | Not reported | 3.5 ± 3.7 (belief in afterlife) 5.4 ± 4.6 (no belief in afterlife) 3.9 ± 4.3 (not sure) |

Not reported | OUT |

| 2004,c Mystakidou,56 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 120 | 62.8% | 81% | 2.9 ± 3.70 | High ⩾7 (8.3%) Strong ⩾11 (5%) |

MP |

| 2004,c Mystakidou,25 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 120 | 62.8% | 81% | 2.9 ± 3.70 | High ⩾7 (8.3%) Strong ⩾11 (5%) |

VAL |

| 2004, Wilson,33 Canada | SISC | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 69 | Not reported | Not reported | 2.81 ± 2.01 patients with a depressive disorder and 0.51 ± 0.91 patients without depressive disorder | ⩾3 (18.8%) | VAL |

| 2005, Albert,35 USA | SAHD and two visual analogue scales | Prospective | Advanced ALS | MDA/ALS Research Centre Hospices | n = 80 | Not reported | 63% | Patients who expressed wish to die according to VAS, scored 12.6 on SAHD | Not reported (18.9%) | MP |

| 2005, Chochinov,46 Canada and Australia | SISC | Cross-sectional | End-stage cancer patients | Inpatients and home-based palliative care services | n = 100 | 55.2% | 78% | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2005,c Chochinov,38 Canada | DDRS | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 189 | 51.2% | 64% | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2005,c Mystakidou,57 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 120 | 77.5% | 81% | 2.9 ± 3.70 | High ⩾7 (8.3%) Strong ⩾11 (5%) |

MP |

| 2005,c Mystakidou,58 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 120 | Not reported | 81% | 2.9 ± 3.70 | High ⩾7 (8.3%) Strong ⩾11 (5%) |

MP |

| 2005, O’Mahony,10 USA | DDRS | Cohort study | Patients in active antineoplasic treatment | Pain and palliative care service | n = 131 | 22.5% | 38% | 0.84 (baseline) 1.38 (follow-up) |

No cut-off (26.6% baseline and follow-up) | MP |

| 2006, Mystakidou,11 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 106 | 56.1% | 87.6% | Not reported | High ⩾7 or strong ⩾11 (28%) | MP |

| 2006, Ransom,51 USA | SAHD | Longitudinal | Advanced cancer patients | Cancer centre | n = 60 couples (patients and caregivers) | Not reported | 21.2% | 2.53 ± 1.86 (T1) 2.55 ± 2.30 (T2) |

⩾10 (0%; T1) ⩾10 (3.3%; T2) |

MP |

| 2006,c Rosenfeld,41 USA | SAHD and DDRS | Cross-sectional | Advanced AIDS patients | Palliative care facility | n = 372 | 27.0% | 87.1% | 2.9 ± 3.3 (SAHD) 0.7 ± 1.1 (DDRS) |

SAHD ⩾ 10 (4.6%) DDRS ⩾ 3 (6.5%) |

MP |

| 2007,c Mystakidou,59 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 102 | Not reported | 81.6% | 2.9 ± 3.70 | ⩾7 (3.9%) ⩾11 (8.8%) |

MP |

| 2007, Rodin,12 Canada | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Outpatient metastatic cancer patients | Oncology hospital | n = 326 | 32.1 | 44.6% | 1.7 ± 2.2 | ⩾10 (1.5%) | MP |

| 2008, Mystakidou,19 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 91 | 46.9% | 81.2% | 3.92 ± 4.91 | ⩾7 (22%) | MP |

| 2008, Mystakidou,17 Greece | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 112 | Not reported | 81.1% | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2009, Olden,52 USA | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care facility | n = 422 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | OUT |

| 2009, Rodin,60 Canada | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Oncology hospital | n = 406 | Not reported | Not reported | 1.74 ± 2.16 | Not reported | MP |

| 2010, Breitbart,53 USA | SAHD | Randomised controlled trial | Advanced cancer patients | Outpatient unit of cancer hospital | n = 90 | Not reported | Not reported | 3.64 (meaning-centred group psychotherapy) 4.0 (Supportive group therapy) |

Not reported | OUT |

| 2010, Breitbart,16 USA | SAHD and DDRS | Prospective | Advanced AIDS patients | Palliative care unit | n = 372 | 27.07% | 87.1% | Not reported | SAHD ⩾ 10; DDRS ⩾ 3 (37.8%) | MP |

| 2010,c O’Mahony,40 USA | DDRS | Cohort study | Patients in active antineoplasic treatment | Pain and palliative care service | n = 64 | Not reported | 55.1% | 0.84 ± 1.59 (baseline) 1.38 ± 2.13 (follow-up) |

Not reported | MP |

| 2010,c Voltz,61 Germany | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 18 | 15% | 31% | Not reported | Not reported | MP |

| 2011, Chochinov,47 Canada, Australia and USA | SISC | Randomised controlled trial | Terminally ill patients | Palliative care (hospice or home) | n = 326 | 21.5% | 36.9% | 0.53 ± 0.88 (dignity therapy) 0.65 ± 129 (standard palliative care) 0.68 ± 1.18 (client-centred care) |

Not reported | OUT |

| 2011,c Price,39 United Kingdom | DDRS | Cross-sectional with 4-week follow-up | Advanced disease patients | Hospice | n = 300 | Not reported | 40% | Not reported | ⩾4 (3.7%, T1) ⩾4 (3.3%, T2) |

MP |

| 2011,c Rayner,18 United Kingdom | DDRS | Cross-sectional | Palliative patients | Palliative care hospice | n = 300 | 15.7% | 40% | Not reported | No cut-off (35.6%) | OUT |

| 2011, Shim,13 Korea | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Cancer patients currently in treatment | Cancer hospital | n = 131 | 46.1 | 69.6% | 2.74 ± 2.34 | ⩾10 (1.7%) | MP/VAL |

| 2013, Julião,42 Portugal | DDRS | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill patients | Palliative care unit | n = 75 | 45.4% | Not reported | Not reported | ⩾4 (20%) | MP |

| 2014, Rosenfeld,54 USA | SAHD | Longitudinal | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care hospital | n = 128 | 8.0% | 12.9% | 1.65 ± 1.4 (low trajectory) 10.00 ± 2.9 (rising trajectory) 4.60 ± 1.3 (falling) 11.13 ± 2.9 (high) |

⩾7 (17.2%; at both time points) | MP |

| 2014, Stutzki,34 Switzerland and Germany | Designed by authors | Longitudinal | ALS patients | ALS centre | n = 66 patients and 62 caregivers | 22.6% | 50.3% | Not reported | ⩾1 (14% baseline; 16% follow-up) |

MP |

| 2014, Villavicencio,15 Spain | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 101 | 14% | 35.4% | 4.99 ± 5.32 | ⩾10 (16.8%) | VAL |

| 2015, Breitbart,55 USA | SAHD | Randomised controlled trial | Advanced cancer patients | Outpatient unit of cancer centre | n = 253 | 7.6% | Not reported | 2.30 ± 3.34 (meaning-centred psychotherapy) 1.89 ± 3.06 (supportive group psychotherapy) |

Not reported | OUT |

| 2015,c Galushko,26 Germany | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 92 | 10.5% | Not reported | 5.09 ± 3.71 | ⩾10 (12%) | VAL |

| 2016, Wang,27 China | SAHD | Cross-sectional | Terminally ill cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 85 | Not reported | Not reported | 5.56 ± 5.19 | Not reported | MP |

| 2016, Wilson,23 Canada | SISC | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer patients | Palliative care unit | n = 377 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ⩾3 (12.2%) | MP |

WTHD: wish to hasten death; SD: standard deviation; MP: main purpose; OUT: outcome variable; VAL: validation; DDRS: Desire for Death Rating Scale; SAHD: Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death; SISC: Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns.

Percentage of total patient population regarded as eligible and who were invited to participate.

Percentage of eligible patients included in the data analysis.

Part of a larger study.

In terms of their design, the majority (n = 37) were cross-sectional studies.

Regarding participants, 48 studies focused directly on patients, while the remaining 2 gathered data from doctor-terminally ill patient pairs. With respect to the clinical diagnosis, 78% of studies (n = 39) involved patients with cancer, 8% (n = 4) concerned patients with HIV/AIDS and 6% (n = 3) patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The analysis of study aims revealed that 58% of the studies included in the review (n = 29) had the assessment of the WTHD as their main purpose (MP), 26% (n = 13) included the assessment of the WTHD as one among other outcome variables (OUT) and 16% (n = 8) were instrument validation studies (VAL).

Characteristics of the instruments used to assess the WTHD

Given that, for the purposes of the present review, we considered modifications of an original instrument as constituting a separate measure, the analysis identified seven different instruments for analysing the WTHD.1,20–22,33–35 Adaptations and validations of instruments in other languages were not considered as separate measures. These instruments consisted of scales,1,20,33 questionnaires,21,34 a series of questions22 and the use of visual analogue scales.35 Table 3 shows the main characteristics of each kind of instrument. The number of items or questions in these instruments varies between 1 and 20. Only one of the instruments21 has been subjected to an explicit process of transcultural adaptation and validation, involving the study of its psychometric properties, in order to develop versions in other languages. In the remainder of this section, we describe the different instruments identified, in chronological order according to the year of publication of the original study.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the different instruments used to assess the WTHD in the included articles.

| Instrument | First author, year | Kind of assessment | Language in which available | Dimensions and Cronbach’s alpha | Items/categories | Response | Range | Cut-off score (original study) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDRS | Chochinov, 199520 | Clinician-rated | English | – | 1 screening item plus a further 3 items if the first item is endorsed | 6-point rating scale | [0–6] | ⩾4 |

| SAHD | Rosenfeld, 199921 | Self-report Clinician-rated |

English21

German26 Greece25 Korean13 Spanish15 Taiwanese27 |

Unidimensional, 0.89 Bidimensional, 0.71 Unidimensional, 0.89 Unidimensional, 0.66 Unidimensional, 0.92 Not reported |

20 items | True/false | [0–20] | 0–3 Low >3 to <10 Moderate ⩾7 High ⩾11 Strong |

| Modified DDRS | Kelly, 20021 | Clinician-rated | English | Unidimensional, 0.86 | 6 items | 5-point Likert response | [0–24] | 0 No wish ⩾1 to ⩽4 Moderate ⩾5 High |

| Questions developed by authors | Tiernan, 200222 | Clinician-rated | English | 4 items | 0–3 rating scale | [0–12] | Score 2 or 3 on any question | |

| Modified DDRS introduced into the SISC | Wilson, 200433 | Clinician-rated | English | – | 1 screening item and a further 3 items if the first item is endorsed | 0–6 point rating | [0–6] | 0 No wish 3 Moderate 6 Extreme |

| Visual analogue scale | Albert, 200535 | Clinician-rated | English | – | 2 visual analogue questions | 1–10 point rating | [1–10] | ⩾8 |

| Questions developed by authors | Stutzki, 201434 | Clinician-rated | German | 1 question about the WTHD 7 questions about plans and ideation |

Numerical rating scale Yes/No |

[0–10] | ⩾1 |

DDRS: Desire for Death Rating Scale; SAHD: Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death; SISC: Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns.

The first instrument for assessing the WTHD was developed by Chochinov et al.20 in a sample of Canadian patients with cancer, concerned by the fact that euthanasia and assisted suicide had become prominent medical and social issues. This instrument, the DDRS, consists of a screening question (‘Do you ever wish that your illness would progress more rapidly so that your suffering could be over sooner?’) which, if endorsed, is followed by a further three questions that form a semi-structured interview. The authors were inspired by the diagnostic interview of the Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia (SADS)36 to design the DDRS. As in the SADS protocol, the interviewer is required to rate the severity of the psychiatric symptoms on 6- or 7-point scales. In the same way, the DDRS enables clinicians to rate patients along a 6-point scale and it has been used in Canada,20,37,38 the United Kingdom,18,39 the United States10,16,21,40,41 and Portugal.42 To our knowledge, the psychometric properties of the original scale have not been reported.

Kelly et al.1 modified the DDRS and produced a 6-item scale whose psychometric properties have been examined. These authors replaced the original scale item that asks patients whether they have ever expressed a desire to hasten death with two separate items that specified the person with whom such a desire had been discussed, namely, with family/friends or with a doctor/nurse. They also added a new item that specifically enquired ‘Have you ever asked a doctor or nurse to do something that might help end your life?’. Each item on this modified scale is rated using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 to 4), such that the total score ranges from 0 to 24. To date, this modified version of the DDRS has been used in four studies.1,43–45

Wilson et al.33 subsequently incorporated a slightly modified version of the DDRS into a broader assessment schedule, the Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns (SISC). This interview explores common issues of clinical relevance in the palliative care context, covering physical and psychosocial symptoms. The latter include the desire or WTHD, the frequency and intensity of which is rated on a 6-point scale (from 0 to 6). The SISC has been used to assess the WTHD in three studies.23,46,47

The cut-off used in studies that have applied the DDRS differs across researchers and/or instrument versions. For their modified version, Kelly et al.1 assigned a cut-off ⩾5 (over a possible range of 0–24) as indicative of a ‘high’ WTHD.1,43–45 Wilson and colleagues23,33 established a cut-off ⩾3 over a possible range of 0–6, whereas studies that have used the original DDRS adopt cut-off scores of ⩾316,21,41 or ⩾420,39,42 over a possible range of 0–6 (see Table 2).

The prevalence of the WTHD in studies that used the DDRS and which report this figure ranges between 3% and 35%. In those studies that applied the original DDRS to patients with advanced and/or terminal disease in the palliative care context, the percentage of patients reporting a WTHD ranges between 6.5% and 15% with a cut-off ⩾3,21,41 and between 3.3% and 20% with a cut-off ⩾4.20,39,42 In the studies by Kelly and colleagues1,43–45 using the modified version of the DDRS, between 14% and 25% of patients expressed a WTHD (cut-off ⩾5), whereas those studies that have applied the SISC (cut-off ⩾3) report percentages between 12.2% and 18.8%23,33 (see Table 2).

The other major instrument for assessing the WTHD is the SAHD, developed by Rosenfeld et al.21 This is a self-report questionnaire (although some adaptations have treated and used it as a clinician-rated measure) containing 20 true/false items, the total score ranging between 0 and 20. The SAHD was originally validated in the United States in a sample of patients with HIV/AIDS21 and then by the same authors 1 year later in patients with far-advanced cancer.24 Transcultural adaptations and validations of the SAHD have since been conducted in Greece,25 South Korea,13 Spain15 and Germany.26 The instrument has also been used in a sample of patients in Taiwan,27 although this Taiwanese version has yet to be formally validated. The different versions of the SAHD have shown adequate internal consistency (Table 3). To date, the instrument has been used in a total of 32 studies: 15 in the United States,6,8,16,21,24,35,41,48–55 8 in Greece,11,17,19,25,56–59 3 in Canada,7,12,60 2 in Germany26,61 and 1 in Australia,62 South Korea,13 Spain15 and Taiwan.27 In 10 studies,6,7,12,13,15,16,24,26,41,51 the authors applied a cut-off ⩾10 as indicating a high WTHD. In all, 4 studies8,11,19,54 used a cut-off ⩾7, 6 used two cut-offs (⩾7 and ⩾11)21,25,56–59 and 12 studies17,27,35,48–50,52,53,55,60–62 did not specify a cut-off.

The prevalence of the WTHD in studies that used the SAHD and which report this figure ranges between 1.5% and 28%, although the cut-off applied was not the same in all cases. In those studies that applied the SAHD to patients with advanced disease in the palliative care context, the percentage of patients reporting a WTHD ranges between 3.9% and 28% with a cut-off ⩾7,11,19,25,54,56–59 between 4.6% and 17% with a cut-off ⩾106,15,24,26,41 and between 5% and 8.8% with a cut-off ⩾11.25,56–59

Tiernan et al.22 drew up four questions to assess the WTHD. The focus of these questions ranged from a passive desire for death to suicidal ideation and a direct reference to assisted suicide: ‘I go to sleep hoping that I won’t wake up’, ‘I think of ending my life, but I would not do it’, ‘I would end my life if I had a chance’ and ‘I wish the doctors would do something to end my life’. Each statement is scored by the patient using a 4-point Likert-type scale (0–3), such that the total score ranges between 0 and 12. The authors presented these questions to 142 patients with far-advanced cancer receiving palliative care in Ireland, only two of whom reported a strong wish for death. To date, this instrument has not been used in subsequent published studies.

Albert et al.35 conducted a study with patients with ALS in the United States. In addition to using the SAHD to assess the WTHD, they asked patients two questions drawn from a national survey of end-of-life decisions and interest in hastened death. These questions, which were answered using a 10-point VAS, were: ‘Have you seriously thought about taking your life?’ and ‘Have you discussed taking your life or asking your doctor or others to end your life?’. A patient was considered as having expressed a wish for hastened death if he or she had strongly endorsed ending life (defined as a score ⩾8 on the VAS) or had stated that he or she had ‘seriously discussed taking (his/her) life or asking (his/her) doctor to end (his/her) life’.

Finally, in a study of patients with ALS in Germany and Switzerland, Stutzki et al.34 used a questionnaire to assess the WTHD and the attitudes of patients (n = 66) and caregivers (n = 62) towards assisted suicide and the use of life-sustaining measures. The WTHD was explored using the question ‘How strong is your current wish to ask others for assistance to end your life prematurely’, which patients answered using a numerical rating scale (0–10). The questionnaire also included questions about advance care planning, suicidal ideation, treatment for depression, whether the patient could imagine asking for physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia, and about communicating the WTHD (yes/no). To date, this instrument has not been used in any other studies.

Methodological quality of instrument validation studies

We applied COSMIN criteria31 to the eight articles1,13,15,21,24–26,33 that reported measurement properties in the context of instrument validation. These studies provided data that enabled us to evaluate a median of five of the nine COSMIN criteria referring to the assessment of measurement properties. No study used item response theory (IRT). Table 4 shows detailed COSMIN ratings of measurement properties for each of the eight articles.

Table 4.

Methodological quality, based on COSMIN criteria,31 of the eight studies reporting measurement properties in the context of instrument validation.

| Instrument | First author, year | BOX A: internal consistency | BOX B: reliability | BOX C: measurement error | BOX D: content validity | BOX E: structural validity | BOX F: hypothesis testing | BOX G: cross-cultural validity | BOX H: criterion validity | BOX I: responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAHD | Rosenfeld, 199921 | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Good | ||||

| SAHD | Rosenfeld, 200024 | Good | Fairb | Excellent | Good | Good | Good | |||

| Modified DDRS | Kelly, 20021 | Good | Good | Poor | ||||||

| SAHD | Mystakidou, 200425 | Excellent | Excellenta,b | Excellent | Excellent | Fair | Goodc | Good | ||

| SISC | Wilson, 200433 | Gooda,b | Excellent | Poor | Good | |||||

| SAHD | Shim, 201113 | Good | Fairc | |||||||

| SAHD | Villavicencio-Chávez, 201415 | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Poor | Goodc | Good | |||

| SAHD | Galushko, 201526 | Good | Excellent | Good | Fair | Fairc | Good |

DDRS: Desire for Death Rating Scale; SAHD: Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death; SISC: Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns.

Empty space: not applicable. For more detailed information regarding the definitions of psychometric properties and the 4-point scale rating, see the COSMIN website (www.cosmin.nl).

Test–retest reliability.

Inter-rater reliability.

Only the quality of the translation procedure was evaluated.

Regarding interpretability, only one study26 reported information about missing items, and none of them detailed the lowest and highest scores possible. Similarly, none of the studies assessed the minimal important change (MIC) or the minimal important difference (MID).

In terms of generalisability, most of the studies involved patients with a mean age between 61 and 66 years. All but one of the eight studies13 were conducted in Western countries.

Rating of psychometric properties

Table 5 shows ratings, based on the criteria of Terwee et al.,32 of the psychometric properties of the instruments described in the aforementioned eight articles. None of the articles provided information relating to the criteria of responsiveness and interpretability. Some criteria, such as reproducibility and floor and ceiling effects, could only be assessed for two25,33 and three articles,21,24,25 respectively.

Table 5.

Ratings of the reported psychometric properties of validated instruments, based on the criteria of Terwee et al.32

| Instrument | First author, year | Content validity | Internal consistency | Criterion validity | Construct validity | Reproducibility (agreement) | Reproducibility (reliability) | Responsiveness | Floor and ceiling effects | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAHD | Rosenfeld, 199921 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| SAHD | Rosenfeld, 200024 | + | + | − | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Modified DDRS | Kelly, 20021 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAHD | Mystakidou, 200425 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| SISC | Wilson, 200433 | + | 0 | + | ? | ? | − | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAHD | Shim, 201113 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAHD | Villavicencio-Chávez, 201415 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAHD | Galushko, 201526 | + | + | − | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

DDRS: Desire for Death Rating Scale; SAHD: Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death; SISC: Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns.

Rating: +: positive (the study by Terwee et al.60 specifies criteria for determining whether the quality of each measurement property can be regarded as positive or negative); ?: indeterminate (doubtful information regarding each psychometric property); −: negative; 0: no information available. For more detailed information regarding the quality criteria for measurement properties of health status questionnaires, see Terwee et al.32 (Table 1, p. 39).

Discussion

This systematic review analysed 50 articles reporting the assessment of the WTHD in patients with advanced disease (which has recently defined by the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care as ‘when one or more conditions become serious enough that general health and functioning decline, and treatments begin to lose their impact’63). We identified and analysed seven instruments of measurement (five different instruments, plus two modified versions of one of these) that have been used for this purpose, the assessment of WTHD in patients with advanced disease.

The review reveals that three instruments22,34,35 were developed by authors for a specific study and they have not subsequently been used in other published researches. By contrast, instruments such as the DDRS20 and, especially, the SAHD21 have been widely used. One aspect that is often lacking, however, is an explicit description of the theoretical framework that guided the development of an instrument, or specific details regarding the construct that the authors are seeking to measure. This lack of conceptual clarity appears to have led to the development of different assessment methods that focus on different aspects of the phenomenon, with the scope of this focus varying from one instrument to another.

Despite these differences, however, a characteristic common to all the instruments is the idea that the WTHD can be understood as a reaction to suffering.1,20,21,33,35 Items referring explicitly to suffering feature in four of the instruments analysed, namely, the original and the two modified versions of the DDRS,1,20,33 and the SAHD.21 Although the items used in the other instruments22,34,35 do not make explicit reference to suffering, the authors do, in their analysis of results, link the WTHD to the presence of intense suffering.

The difficulty of defining the construct of the WTHD is one of the main limitations associated with the instruments analysed. For example, the problem of how to discriminate between a ‘genuine’ WTHD and simply the acceptance of death in an end-of-life context is mentioned in a number of studies, mainly with respect to the SAHD.6,15,22,39 The authors of this instrument suggest using a cut-off score ⩾10 (range, 0–20) as a way of overcoming this potential problem,6 although the decision as to whether a lower or higher cut-off should be used will ultimately depend on the specific research objectives.21,24 The variable or arbitrary nature of the cut-off scores used in different studies is an issue that also affects the DDRS. These differences in cut-off scores are one of the aspects that make it difficult to compare results across studies.

Another aspect that can be observed in several of the studies that applied one of the instruments is the relatively low proportion of patients, from among those who were eligible for inclusion, who finally participated. This reflects a common challenge faced by researchers working with vulnerable populations64–66 and highlights the potential difficulty of conducting this kind of assessment in the clinical setting. In some of the studies that administered the SAHD, for instance, only a minority of eligible patients were ultimately able to participate: in three studies conducted in the United States,49,51,54 between 13% and 26% of eligible patients provided analysable data, while the corresponding figure in studies conducted in Germany61 and Spain15 was 31% and 35%, respectively. It should be noted, however, that this instrument (the SAHD) was originally developed for use in research rather than in clinical practice.21

The DDRS, by contrast, was designed for clinician administration in the context of a clinical interview, and this may account for the higher rates of patient participation observed in studies that have used this instrument. In 6 of the 14 studies16,20,38,41,44,46 that provide such data, participation was ⩾60%, and in no case was it below 37%. With respect to the other instruments used to assess the WTHD, participation rates never exceeded 65%.

Regarding the study population, the review shows that participation rates were highest (>60%) in studies involving non-oncology populations,16,34,35,41 for which reported rates were 25%–35% higher than in samples of patients with cancer, who were generally in the advanced or terminal stage of the disease.

In terms of the methodological quality of validation studies that examined the measurement properties of an instrument, we found that the data reported in most cases meant that only some of the criteria could be evaluated. This lack of information regarding some properties is a common problem faced by systematic reviews of measurement instruments.67–71 None of the instruments identified was investigated using IRT, an approach that would perhaps enable a more specific examination of item adequacy, as well as the establishment of a risk score for the WTHD.72 Regarding the adequacy of the psychometric properties of the instruments considered, more information than is reported by the articles would be required in order to state categorically whether or not the different measures show adequate properties in terms of COSMIN criteria. The difficulty of evaluating all the quality criteria needs to be seen in the context of sample characteristics, that is, patients with advanced disease and short survival.

Strengths and limitations of this review

A strength of this review is that studies were selected independently by two researchers, thus minimising the possibility of selection errors. Furthermore, the methodological quality of studies that examined measurement properties was assessed by means of specific instruments of reference,30,32 such that the results can be regarded as objective. We also believe that by describing the wide range of instruments available in the context of advanced disease, this review provides both clinicians and researchers with an overview of these tools and allows them to consider their strengths and limitations.

In our view, the difficulty of reviewing such a varied set of articles ultimately constitutes one of the contributions of this report. We have managed to synthesise an extensive body of information, although the diverse range of designs used by studies that describe instruments undoubtedly makes comparison difficult.

The lack of an agreed conceptual framework for defining the WTHD poses a challenge when it comes to studying specific clinical aspects of this phenomenon. In this respect, it should be noted that a recent study involving a nominal group and an international Delphi process has proposed a consensus definition of the WTHD,73 one which could serve as a platform for the future design and evaluation of instruments to assess the WTHD.

Due to the inclusion criteria for this review, the results are applicable only to adults. We acknowledge, however, that the WTHD has also been studied in the paediatric population,74 as well as in the elderly in general.75,76 We also excluded two studies that, despite examining the WTHD in a palliative care setting, did so on the basis of patients’ spontaneous expression of such a wish, rather than through application of an instrument. This was the case of the study by Güell et al.,77 who used a semi-structured interview to explore the reasons behind the desire-to-die statements made by terminally ill cancer patients. Similarly, Freeman et al.78 studied a sample of palliative home care patients who had voluntarily expressed the wish to die to relatives, friends or clinical staff. Finally, we excluded a study regarding the desire to die or for hastened death among Japanese palliative care patients because the data were derived from a survey of the patients’ families.9

In summary, seven different instruments have been used for the measure of the WTHD. The SAHD and the DDRS (including its modified versions) are the instruments that have been most widely used to assess the WTHD, with one or the other featuring in 48 of the 50 studies reviewed. Unfortunately, the data regarding their measurement properties are limited and do not enable us to establish the superiority of one instrument over the other. However, if their characteristics are considered alongside those of the studies in which they have been used, it appears that the DDRS is more geared towards clinical practice, whereas the SAHD is perhaps best suited to research. In fact, the DDRS, which comprises just four questions that readily yield a total score, has been applied exclusively in the clinical context, whereas the SAHD was originally designed as a self-report research tool21 and may be too long (20 items) for routine clinical use. Furthermore, some aspects of the SAHD, such as its direct wording, may make it less suitable for patients who are physically and/or emotionally fragile; it is worth noting in this regard that some authors have chosen to use it as a clinician-administered tool subsequent to adequate preparation of patients.15,26 Nonetheless, the SAHD remains the most widely used instrument to date, and the one whose psychometric properties have been most often analysed. Versions of this instrument are currently available in five languages other than the original English.

The prevalence data for the WTHD obtained through application of the SAHD and the DDRS reveal, in both cases, considerable variability across studies. In samples of palliative care patients with advanced and/or terminal disease, rates are between 3.3% and 20% for the DDRS and between 3.9% and 28% for the SAHD. However, these figures should be interpreted with caution due to methodological differences between studies with regard to sample characteristics, the percentage of eligible patients who actually participated or the study design itself.

The results of this review suggest that further studies are needed to assess the unknown measurement properties of both the SAHD and the DDRS (including its modified versions). Another point to consider is the growing awareness of the crucial role that patients themselves play in healthcare processes. In this respect, it is worth noting that for none of the seven instruments identified in this review were the views of patients explicitly gathered as a key part of the original design process or during subsequent examination of measurement properties, although some more recent studies have begun to address this issue.15,79 In our opinion, this is an aspect that requires closer attention in the future.

To conclude, this systematic review provides an exhaustive analysis of the various instruments that have so far been used to assess the WTHD. It has also explored the methodological quality of validation studies that have examined the measurement properties of these instruments and offers a rating of the reported properties. We believe that the results of the review could help both clinicians and researchers in this field to choose the assessment tool that is best suited to their goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan Nance for his contribution to translating and editing the manuscript. M.B.-P. and C.M.-R. contributed equally to this work. The authors would also like to thank Keith Wilson for his valuable contribution reviewing and commenting on the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors would like to thank the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) for funding this research through project PI14/00263. They are also grateful for the support given by aecc-Catalunya contra el Càncer – Barcelona; WeCare Chair: End-of-life care at the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya and ALTIMA.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Kelly B, Burnett P, Pelusi D, et al. Terminally ill cancer patients’ wish to hasten death. Palliat Med 2002; 16(4): 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johansen S, Holen JC, Kaasa S, et al. Attitudes towards, and wishes for, euthanasia in advanced cancer patients at a palliative medicine unit. Palliat Med 2005; 19(6): 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology 2011; 20(8): 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hudson PL, Kristjanson LJ, Ashby M, et al. Desire for hastened death in patients with advanced disease and the evidence base of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2006; 20(7): 693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chavez C, Tomas-Sabado J, et al. What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS ONE 2012; 7(5): e37117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000; 284(22): 2907–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones JM, Huggins MA, Rydall AC, et al. Symptomatic distress, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in hospitalized cancer patients. J Psychosom Res 2003; 55(5): 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Burton L, et al. The role of cognitive impairment in desire for hastened death: a study of patients with advanced AIDS. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003; 25(3): 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morita T, Sakaguchi Y, Hirai K, et al. Desire for death and requests to hasten death of Japanese terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized inpatient palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004; 27(1): 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Mahony S, Goulet J, Kornblith A, et al. Desire for hastened death cancer pain and depression: report of a longitudinal observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005; 29(5): 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Katsouda E, et al. The role of physical and psychological symptoms in desire for death: a study of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 2006; 15(4): 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33(6): 661–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shim E, Hahm B. Anxiety, helplessness/hopelessness and desire for hastened death in Korean cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2011; 20(3): 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nissim R, Gagliese L, Rodin G. The desire for hastened death in individuals with advanced cancer: a longitudinal qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2009; 69(2): 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Villavicencio-Chávez C, Monforte-Royo C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. Physical and psychological factors and the wish to hasten death in advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology 2014; 23(10): 1125–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Impact of treatment for depression on desire for hastened death in patients with advanced AIDS. Psychosomatics 2010; 51(2): 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilika E, et al. The experience of hopelessness in a population of Greek cancer patients receiving palliative care. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2008; 54(3): 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rayner L, Lee W, Price A, et al. The clinical epidemiology of depression in palliative care and the predictive value of somatic symptoms: cross-sectional survey with four-week follow-up. Palliat Med 2011; 25(3): 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Prapa E, et al. Predictors of spirituality at the end of life. Can Fam Physician 2008; 54(12): 1720–1721.e5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152(8): 1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, et al. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/AIDS: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156(1): 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tiernan E, Casey P, O’Boyle C, et al. Relations between desire for early death, depressive symptoms and antidepressant prescribing in terminally ill patients with cancer. J Roy Soc Med 2002; 95(8): 386–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilson KG, Dalgleish TL, Chochinov HM, et al. Mental disorders and the desire for death in patients receiving palliative care for cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; 6(2): 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Galietta M, et al. The schedule of attitudes toward hastened death: measuring desire for death in terminally ill cancer patients. Cancer 2000; 88(12): 2868–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mystakidou K, Rosenfeld B, Parpa E, et al. The schedule of attitudes toward hastened death: validation analysis in terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2(4): 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galushko M, Strupp J, Walisko-Waniek J, et al. Validation of the German version of the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death (SAHD-D) with patients in palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(3): 713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang YC, Lin CC. Spiritual well-being may reduce the negative impacts of cancer symptoms on the quality of life and the desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2016; 39(4): E43–E50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Brit J Manage 2003; 14(3): 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010; 19(4): 539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res 2012; 21(4): 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60(1): 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson KG, Graham ID, Viola RA, et al. Structured interview assessment of symptoms and concerns in palliative care. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49(6): 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stutzki R, Weber M, Reiter-Theil S, et al. Attitudes towards hastened death in ALS: a prospective study of patients and family caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2014; 15(1–2): 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albert SM, Rabkin JG, Del Bene ML, et al. Wish to die in end-stage ALS. Neurology 2005; 65(1): 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35(7): 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: A cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet 2002; 360(9350): 2026–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Understanding the will to live in patients nearing death. Psychosomatics 2005; 46(1): 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Price A, Lee W, Goodwin L, et al. Prevalence, course and associations of desire for hastened death in a UK palliative population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1(2): 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Mahony S, Goulet JL, Payne R. Psychosocial distress in patients treated for cancer pain: a prospective observational study. J Opioid Manag 2010; 6(3): 211–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Gibson C, et al. Desire for Hastened Death Among Patients with Advanced AIDS. Psychosomatics 2006; 47(6): 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Julião M, Barbosa A, Oliveira F, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with desire for death in patients with advanced disease: Results from a Portuguese cross-sectional study. Psychosomatics 2013; 54(5): 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kelly B, Burnett P, Pelusi D, et al. Factors associated with the wish to hasten death: A study of patients with terminal illness. Psychol Med 2003; 33(1): 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kelly B, Burnett P, Badger S, et al. Doctors and their patients: a context for understanding the wish to hasten death. Psychooncology 2003; 12(4): 375–384 10p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kelly BJ, Burnett PC, Pelusi D, et al. Association Between Clinician Factors and a Patient’s Wish to Hasten Death: Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and Their Doctors. Psychosomatics 2004; 45(4): 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(24): 5520–5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12(8):753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rabkin JG, Wagner GJ, Del Bene M. Resilience and distress among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and caregivers. Psychosom Med 2000; 62(2): 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 2003; 361(9369): 1603–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McClain-Jacobson C, Rosenfeld B, Kosinski A, et al. Belief in an afterlife, spiritual well-being and end-of-life despair in patients with advanced cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004; 26(6): 484–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ransom S, Sacco WP, Weitzner MA, et al. Interpersonal factors predict increased desire for hastened death in late-stage cancer patients. Ann Behav Med 2006; 31(1): 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Olden M, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Measuring depression at the end of life: Is the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale a valid instrument? Assessment 2009; 16(1): 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2010; 19(1): 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Marziliano A, et al. Does desire for hastened death change in terminally ill cancer patients? Soc Sci Med 2014; 111: 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy: An Effective Intervention for Improving Psychological Well-Being in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(7): 749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Katsouda E, et al. Influence of pain and quality of life on desire for hastened death in patients with advanced cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004; 10(10): 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mystakidou K, Rosenfeld B, Parpa E, et al. Desire for death near the end of life: The role of depression, anxiety and pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005; 27(4): 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Katsouda E, et al. Pain and desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2005; 28(4): 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilika E, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and sleep in cancer patients’ desire for death. Int J Psychiatry Med 2007; 37(2): 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, et al. Pathways to distress: The multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68(3): 562–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Voltz R, Galushko M, Walisko J, et al. End-of-life research on patients’ attitudes in Germany: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18(3): 317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kissane DW, Wein S, Love A, et al. The demoralization scale: a report of its development and preliminary validation. J Palliat Care 2004; 20(4): 269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. The coalition to transform advanced care (CTAC) policy agenda. Options to transform advanced care, http://www.thectac.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/C_TAC-Policy-Agenda.pdf (2015, accessed 30 July 2016).

- 64. Chen EK, Riffin C, Reid MC, et al. Why is high-quality research on palliative care so hard to do? Barriers to improved research from a survey of palliative care researchers. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(7): 782–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. O’Mara AM, St Germain D, Ferrell B, et al. Challenges to and lessons learned from conducting palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37(3): 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kars MC, Van Thiel GJ, Van der Graaf R, et al. A systematic review of reasons for gatekeeping in palliative care research. Palliat Med 2016; 30(6): 533–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Heymans MW, et al. Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2012; 21(4): 659–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Barr PJ, Scholl I, Bravo P, et al. Assessment of patient empowerment – a systematic review of measures. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(5): e0126553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Muller E, Zill JM, Dirmaier J, et al. Assessment of trust in physician: a systematic review of measures. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(9): e106844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Collins SA, Currie LM, Bakken S, et al. Health literacy screening instruments for eHealth applications: a systematic review. J Biomed Inform 2012; 45(3): 598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Paalman CH, Terwee CB, Jansma EP, et al. Instruments measuring externalizing mental health problems in immigrant ethnic minority youths: a systematic review of measurement properties. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(5): e63109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hambleton R, Swaminathan H, Rogers H. Fundamentals of item response theory. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Balaguer A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, et al. An international consensus definition of the wish to hasten death and its related factors. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(1): e0146184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dussel V, Joffe S, Hilden JM, et al. Considerations about hastening death among parents of children who die of cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010; 164(3): 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Scott R, et al. Factors associated with the wish to die in elderly people. Age Ageing 1995; 24(5): 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim YA, Bogner HR, Brown GK, et al. Chronic medical conditions and wishes to die among older primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 2006; 36(2): 183–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Güell E, Ramos A, Zertuche T, et al. Verbalized desire for death or euthanasia in advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(2): 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Freeman S, Smith TF, Neufeld E, et al. The wish to die among palliative home care clients in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 29 February 2016. DOI: 10.1186/s12904-016-0093-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Voltz R, Galushko M, Walisko J, et al. Issues of ‘life’ and ‘death’ for patients receiving palliative care – comments when confronted with a research tool. Support Care Cancer 2011; 19(6): 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]