Abstract

Background:

Dignity therapy is psychotherapy to relieve psychological and existential distress in patients at the end of life. Little is known about its effect.

Aim:

To analyse the outcomes of dignity therapy in patients with advanced life-threatening diseases.

Design:

Systematic review was conducted. Three authors extracted data of the articles and evaluated quality using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Data were synthesized, considering study objectives.

Data sources:

PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and PsycINFO. The years searched were 2002 (year of dignity therapy development) to January 2016. ‘Dignity therapy’ was used as search term. Studies with patients with advanced life-threatening diseases were included.

Results:

Of 121 studies, 28 were included. Quality of studies is high. Results were grouped into effectiveness, satisfaction, suitability and feasibility, and adaptability to different diseases and cultures. Two of five randomized control trials applied dignity therapy to patients with high levels of baseline psychological distress. One showed statistically significant decrease on patients’ anxiety and depression scores over time. The other showed statistical decrease on anxiety scores pre–post dignity therapy, not on depression. Nonrandomized studies suggested statistically significant improvements in existential and psychosocial measurements. Patients, relatives and professionals perceived it improved end-of-life experience.

Conclusion:

Evidence suggests that dignity therapy is beneficial. One randomized controlled trial with patients with high levels of psychological distress shows DT efficacy in anxiety and depression scores. Other design studies report beneficial outcomes in terms of end-of-life experience. Further research should understand how dignity therapy functions to establish a means for measuring its impact and assessing whether high level of distress patients can benefit most from this therapy.

Keywords: Dignity therapy, end of life, terminal, palliative care, psychotherapy

What is already known about the topic?

DT was recently developed to relieve psychological and existential distress in patients at end of life. Originally was conceived for patients with low levels of distress.

DT seems to affect several dimensions of patients but the process and the way of measuring the impact of the intervention are not clear.

What this paper adds?

This paper provides a critical and comprehensive view about DT including primary and secondary study results, which is key to have an overview of the therapy.

This review offers for the first time the vision of all the participants in the process: patients, relatives and health professionals, showing that they are satisfied and would recommend DT as they find it helpful and useful.

This paper points out that DT might be more beneficial for patients with high levels of distress, a group population where initially DT was not recommended.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

The literature suggest benefits from DT for end of life patients as patients, families and health professionals found it helpful and are satisfied with the intervention.

Patients with high levels of distress seem to benefit more from DT, for that reason further research is needed to prove this.

Evidence suggests that DT can be adapted for patients with moto neurone disease and for the elderly.

Background

Recent years have seen significant progress towards controlling physical symptoms associated with advanced disease, but when it comes to related emotional aspects and addressing patients’ psychosocial and spiritual difficulties progress has been less obvious.1

As a disease progresses and the end approaches, emotional suffering increases and patients’ sense of dignity is easily shaken.2 In this context, Chochinov2 developed in 2002 dignity therapy (DT), a brief psychotherapy based on an empirical model of dignity that begins with reflection on why some patients with advanced disease wish to die, while others find serenity and a desire to enjoy their last days.

DT is a brief, individualized psychotherapy and aims to relieve psycho-emotional and existential distress and to improve the experiences of patients whose lives are threatened by illness. This therapy offers patients an opportunity to reflect on issues that are important to them or other things that they would like to recall or transmit to others.

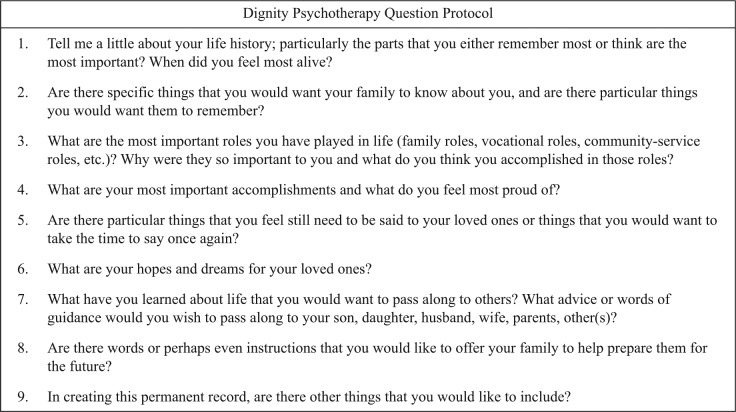

This psychotherapy’s protocol begins giving to the patient nine standard questions which are options for the patients’ consideration and reflection about what they want to say (Figure 1). The questions will guide a conversation with a DT-trained healthcare professional. Patients are given the questions in advance in order to familiarize themselves with the possibilities DT provides in terms of broaching areas they may wish to discuss. The session is recorded, transcribed and edited, after which a legacy document is produced and delivered to the patient.

Figure 1.

Dignity psychotherapy question protocol.

DT stands out for its simplicity and for its ability to enhance the meaning, direction and dignity of life for patients and their families.3 There is no evidence in how DT really works. There is lack of a comprehensive perspective of the different stakeholders who participate in the process (patient, family and health professionals) and of the cultural context. This article presents a comprehensive systematic literature review of studies in which DT has been used for patients with life-threatening diseases.

Design

A comprehensive systematic review4 using PRISMA guideline was conducted.5

Search strategy

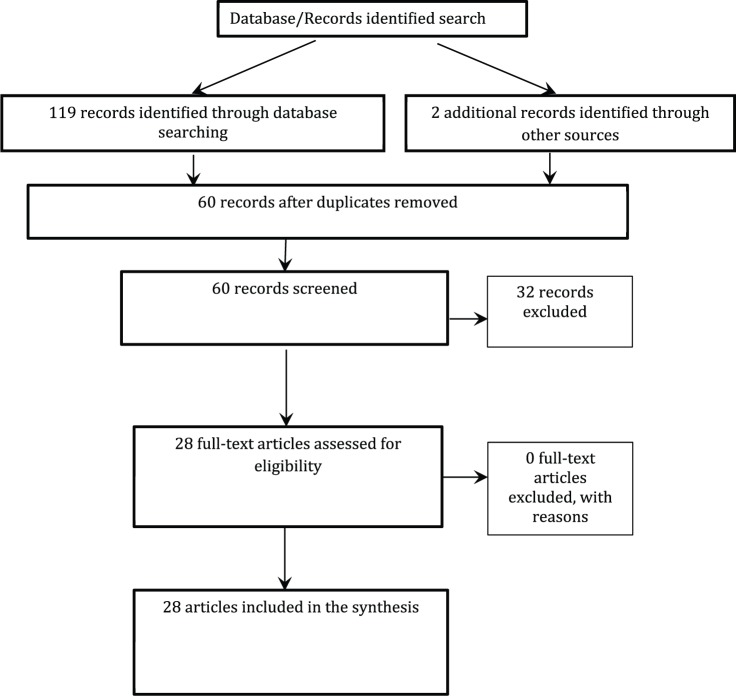

A sensitive search looking for articles, published in English and Spanish between January 2002 and January 2016, including the term ‘DT’ was carried out in PubMed (n = 49 articles), CINAHL (n = 30 articles), Cochrane Library (n = 15 articles) and PsycINFO (n = 25 articles) (Figure 2). Additional studies were identified by contacting experts in DT and searching bibliographies.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of systematic review process.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: DT studies in patients with advanced life-threatening diseases, regardless of the design. Editorials, commentaries and publications on research protocols were excluded. Articles were first selected on the basis of title and abstract and then filtered after reading the complete article. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus among four researchers.

Data collection and analysis process

Independent data extraction from articles was made by three authors using predefined data template (aim, type of study, sample, data collection, results). The quality of articles was evaluated through the tools developed by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) to read and check critically health research. These tools consist of checklists with screening questions and hints to assess and interpret articles’ quality considering methodological issues.6

Data were synthesized, considering the studies’ objectives and the results, and are presented in thematic areas.

Results

In total, 121 articles were identified. After removing duplicates and the title and abstract screening, 28 articles were included. All but five articles7–11 scored above 7/10 with the CASP critical reading process (Table 1). The studies included were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 7), the United States (n = 5), Canada (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Denmark (n = 2), Portugal (n = 3), Sweden (n = 1), Japan (n = 2) and Spain (n = 2).

Table 1.

Articles by thematic area and CASP score.

| Article | Effectiveness | Suitability/feasibility | Satisfaction | Adaptation | CASP score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passik et al.12 | ✓ | 8 | |||

| Chochinov et al.13 | ✓ | 8.5 | |||

| McClement et al.7 | ✓ | 6 | |||

| Houman et al.14 | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Chochinov et al.15 | ✓ | 8 | |||

| Hall et al.16 | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||

| Montross et al.17 | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| Akechi et al.8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |

| Chochinov et al.18 | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Hall et al.19 | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Goddard et al.20 | ✓ | 8 | |||

| Hall et al.21 | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Hall et al.22 | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Hall et al.23 | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| Johns et al.9 | ✓ | 6 | |||

| Juliao et al.24 | ✓ | 8 | |||

| Montross et al.25 | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| Bentley et al.26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 |

| Bentley et al.27 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 |

| Houmann et al.28 | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Javaloyes et al.10 | ✓ | 4 | |||

| Juliao et al.29 | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Vergo et al.30 | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| Aoun et al.31 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 |

| Johnston et al.32 | ✓ | 7 | |||

| Juliao et al.33 | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Lindquist et al.34 | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||

| Rudilla et al.11 | ✓ | 6 |

CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.6

The results are grouped on effectiveness of DT, satisfaction, suitability and feasibility, adaptation to other cultures and populations, and each article’s contribution to the various themes is shown in Table 1.

Effectiveness of DT

Clinical trials

Five randomized studies were identified.11,15,16,19,24,29,33 Chochinov’s group conducted the first randomized study on DT with 441 patients receiving palliative care (PC) with advanced disease and a life expectancy equal to or less than 6 months.15 Their research aimed to determine whether or not DT (n = 108) is better than standard PC (n = 111) and client-centred care (CCC) (n = 107) in terms of reducing psychological, existential, and spiritual distress. CCC is a type of psychotherapeutic support approach that focuses on non-generativity themes, that is, on here-and-now issues. Different measurements were implemented at the beginning and at the completion of the intervention: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual well-being (FACIT-Sp), a scale that evaluates spiritual well-being; the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI), to evaluate distress related to patient dignity and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), to evaluate anxiety and depression in the hospital setting. In addition, two quality-of-life measurements, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and a scale that measures the will to live, were used.

They found that patients who participated in the study had low baseline levels of distress, assessed by HADS. The post-intervention scores showed DT group had decreased depression scores and increased anxiety scores although these were not significant15 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of selected articles.

| Author (year), country | Main objective | Type of study | Sample | Data collection | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passik et al.12 (2004), USA | Assess the feasibility of DT via telemedicine for patients in their homes. | Single-group pre–post trial of DT via telemedicine. | Patients with cancer in home hospice care (N = 8). | ZSDS. PUBS. Single item for depression. Satisfaction survey. |

All subjects were able to complete the assessment, except one who died. Largely comfortable with the videophone technology ( = 4.43, SD = 0.79). |

| Chochinov et al.13 (2005), Canada | Establish the viability of DT and determine its impact on psychosocial and existential distress. | Quasi-experimental study. | Patients with terminal cancer (N = 100). | Before and after DT: Assessment through asking a question: depression, dignity, anxiety, pain, hope, wanting to die or commit suicide and well-being. QoL (2 items). ESAS. DTPFQ. |

Post-intervention measure

Suffering: z = −2.00, p = 0.023. Depression: z = −1.64, p = 0.05. Dignity: z = −1.37, p = 0.085. Family support correlated with Meaning in life: r = 0.480, p < 0.001. Sense of direction: r = 0.562, p = 0.001. Weakly with sense of suffering: r = 0.327, p = 0.001. Desire to live: r = 0.387, p < 0.001 Psychosocial distress correlated with Quality of life: r = −0.220, p = 0.028. Satisfaction with QoL: r = −0.237, p = 0.018. Desire of death: r = 0.192, p = 0.55. Satisfaction survey: 91% were satisfied with the intervention. 86% considered it useful or very useful. 76% stated that it increased their sense of dignity. 68% and 67% stated that DT increased their ‘sense of purpose’ and ‘sense of meaning’. 47% DT increased their desire to live. 81% DT helped or would help their families. |

| McClement et al.7 (2007), Canada | Explore DT’s impact on families and patients from a family point of view. | Qualitative study. | Family members of patients who had died (N = 60). | Closed and open questions about DT’s impact on family members and patients. |

Families’ view of DT’s influence on the patient: 95% thought that DT helped them. It facilitated the expression of feelings. 78% said it increased their sense of purpose. 65% said it helped in preparing for death and that it is important for patient care. DT helps to assess the essentials in life. DT’s influence on the family: 78% DT document helped in mourning process. 95% would recommend DT for other patients. |

| Houmann et al.14 (2010), Denmark | Assess the acceptability and viability of DT between Danish healthcare professionals and cancer patients. | Qualitative study. | Healthcare professionals (n = 10) and cancer patients (n = 20). | Semi-structured interview with healthcare professionals. DTPFQ. |

The presence of problematic terms might suggest the patient’s imminent death. Cognitively demanding questions. Culturally inappropriate ways to refer to the self (pride, achievement). DT is understandable and relevant in Danish culture, but needs some adjustments. |

| Chochinov et al.15 (2011), Canada | Evaluate whether DT could mitigate distress or enhance patient experience. | RCT Three different groups: DT versus client-centred care (CCC) versus standard care (PC). |

Patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care in hospitals, hospices and homes in Canada, United States and Australia (N = 441). DT: (n) = 165. PC: (n) = 140. CCC: (n) = 136. |

Before and after DT: ESAS PDI HADS FACIT-PAL SISC: 7 items DTPFQ. |

Pre-intervention scores: HADS-Depression: DT = 5.86, PC = 6.03, CCC = 6.30. HADS-Anxiety: DT = 5.22, PC = 5.34, CCC = 5.76. Post-intervention scores: HADS-Depression: DT = 5.64, PC = 6.19, CCC = 6.38. HADS-Anxiety: DT = 5.81, PC = 5.20, CCC = 5.38. No p value pre–post facilitated. Satisfaction measurements: Intervention is helpful: DT = 4.23, PC = 3.50, CCC = 3.72, p < 0.0001. Perceptions on quality of life: DT = 3.54, PC = 2.96, CCC = 2.84, p = 0.001. Sense of dignity: DT = 3.52, PC = 3.09, CCC = 3.11, p = 0.002. Sadness or depression: DT = 3.11, PC = 2.57, CCC = 2.65, p = 0.009. |

| Hall et al.16 (2011), UK | Evaluate DT’s effectiveness in reducing distress in patients with advanced cancer. | RCT Two groups: DT versus DT standard palliative care. |

Cancer patients (N = 45) DT (intervention; n = 22) Standard care (control; n = 23) |

Data collection in face-to-face interviews before the study (T0), a week (T1) and 4 weeks (T2) after DT: PDI. Secondary outcome: HHI. HADS. Quality of life (EQ-5D). Likert scale. DTPFQ. |

PDI: Control: T0 = 46.13, T1 = 39.40, T2 = 42.10. Intervention: T0 = 43.00; T1 = 42.00, T2 = 43.63. Hope: Control: T0 = 37.35; T1 = 35.87; T2 = 35.30. Intervention: T0 = 37.09, T1 = 38.00, T2 = 37.50. Only difference at T1 in hope: = 2.55 (95% CI: −4.73 to −0.36, p = 0.02) DT versus Control at 4 weeks: Helpful: = 0.63 (95% CI: −1.22 to −0.04; p = 0.04). Sense of purpose: = 1.16 (95% CI: −2.08 to −0.24; p = 0.02). Meaning: = 0.85 (95% CI: −1.78 to 0.09; p = 0.07). Family support: = 1.07 (95% CI: −2.22 to 0.08; p = 0.07). |

| Montross et al.17 (2011), USA | Provide practical information about employing DT in hospice. | Qualitative study | Community-based hospice patients (N = 27). | Interviews. | Patients talked about autobiographical information, love and life lessons and accomplishments. Range cost for patients’ transcripts: US$27.00–US$143.75. |

| Akechi et al.8 (2012), Japan | Evaluate the feasibility of DT in the Japanese population. | Transversal study. | One hospice and two hospitals. Adult advanced cancer patients (N = 11). |

Participation rate of the eligible patients. Completion rate of participants DTPFQ. |

86% refusal rate. DT participants’ self-report: 67% usefulness for improving dignity. 56% beneficial, improvement in meaning and usefulness for sense of well-being. 78% helpful for family. |

| Chochinov et al.18 (2012), Canada | Evaluate the feasibility of DT in the elderly. | Transversal study. | 12 cognitively intact and 11 cognitively impaired, frail elderly people in long-term care. 24 relatives. 12 health care providers (HPC). |

Examination of prominent themes that emerged from transcribed DT narratives. Family proxies: a modified post-intervention feedback questionnaire and a feedback questionnaire 2 months post-intervention. Health professionals (HP): questionnaire 2 months post-intervention. |

Cognitively intact residents: 9 found DT helpful and half useful for their families. DT helpful for residents: Families of cognitively intact patients: 4/5. Families of cognitively impaired: 0/9. DT important component of residents’ care: Families of cognitively intact patients: 3/5. Families of cognitively impaired: 3/9. HPC value for themselves: Help provide care to impaired residents: 5/7 HP. Help appreciate impaired resident: 6/7 HP. Help provide care to cognitive intact residents: 4/7 HP. Help appreciate cognitive intact resident: 6/7 HP. |

| Hall et al.19 (2012), UK | Evaluate the acceptability, effectiveness and adaptability of DT to reduce patients’ distress in nursing homes. | RCT. | Older people living in nursing homes with no major cognitive impairment (N = 60). Control group (n = 29): standard psychological and spiritual care. Intervention group (n = 31): DT + standard care. |

Baseline demographic data: Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration test, Karnofsky scores, Barthel age, gender, ethnic group. Face-to-face data collection at baseline (T1), at 1 week (T2) and 8 weeks (T3) follow-up: PDI. GDS. Herth Hope Index. Quality of life (EQ-5D). 2 items for measure of quality of life. Feasibility measures: number of visits, therapy duration and so on. Acceptability of DT measure: ranking whether participating in DT or in the study (control group) helped them or their family. Interviewed recipients of ‘generativity’ documents. |

PDI: T0: C = 41.75; I = 39.00; p = 0.39. T1: C = 42.44; I = 40.22; p = 0.53. T2: C = 35.29; I = 34.93; p = 0.64. Meaning in life: T1: C = 3.50; I = 4.00; p = 0.04. T2: C = 3.76; I = 4.00; p = 0.49. Help their families: T1: C = 3.16; I = 3.82; p = 0.02. T2: C = 3.00; I = 4.00; p = 0.01. |

| Goddard et al.20 (2013), UK | Explore patients’ experiences in nursing homes (CH) where DT is used from the point of view of the family. | Quasi-experimental study. | Families that received the transcribed document (N = 14). | Semi-structured telephone or in-person interviews. |

Family point of view: The document: Participants were satisfied and grateful for making it. Impact on residents: Positive assessment of interaction with the therapist. Impact on the family: opportunity to learn more about the patient and to encourage communication was positive. Impact on CHs: document improves the caregiver–patient relationship. DT benefits patients’ end-of-life experience, as well as that of their families, and they would recommend it. Cognitive impairment requires those who administer DT to consider who would benefit from it and the need to make changes to it because of family involvement. |

| Hall et al.21 (2013), UK | Explore the impact of DT in advanced cancer patients who suffer from stress. | Case study approach, secondary analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from a mixed-methods RCT from three participants. | Hospital-based palliative care teams. 17 patients received DT; 3 with highest dignity-related distress selected for the case studies. |

Outcome measures collected in face-to-face interviews at baseline, at 1 and 4 weeks post-intervention: PDI. Rating of perceived benefits of DT at completion and at follow-ups. Qualitative interviews exploring patients’ views of DT and those who received generativity documents. |

All thought that DT had helped them and would help their families. PDI: Beverley: T1 = 94, T2 = 65, T3 = 80. Eve: T1 = 65, T2 = 50, T3 = 61. Sheila: T1 = 62, T2 = 75, T3 = 52. |

| Hall et al.22 (2013), UK | Explore and compare participants’ views on taking part in randomized DT study. | Qualitative part of a bigger RCT study (Hall et al., 2012). | Elderly residents with no cognitive impairment living in one of the 15 care homes (N = 49). Intervention (DT) (n = 25) Control (n = 24). |

See Hall et al.19 (2012) All residents still in the study at follow-up were interviewed. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews at 1 week (25/29 control group and 24/31 intervention group) and 8 weeks (21 control group and 24/15 intervention group) about views on the therapy and/or taking part in the study. Interviewer different from the therapist. Framework analysis. |

Unique themes in the intervention group: views on the generativity document, generativity and reminiscence. Six themes emerged in both groups: refocusing, making a contribution, interaction with the researcher or therapist, diversion and not helping with their problems and cognitive impairment. Study describes benefits of the DT, some difficulties regarding patient cognitive impairment were observed. |

| Hall et al.23 (2013), UK | To explore the views of study and control group participants concerning the benefits of taking part in DT. | Qualitative part of a bigger RCT study (Hall et al., 2012). | 45 adult cancer patients referred to palliative care teams. Intervention (DT, n = 22) Control (n = 23). |

All participants who remained in the study at follow-up were interviewed. Patients interviewed at the 1-week (n = 29) and 4-week follow-up (n = 20). Interviews with families (n = 9) of patients in DT group. Framework analysis. |

Unique theme of DT group: generativity. Prevalent themes in both groups were hopefulness (participants: 6 DT vs 5 control) and tenor of care (participants: 6 DT vs 8 control). Prevalent themes in DT group: pseudo life review (participants: 9 DT vs 2 control); reminiscence (participants: 8 DT vs 2 control) and potential impact on relationships (participants: 5 DT vs 1 control). Patients and family members explained that DT was helpful for them. |

| Johns et al.9 (2013), USA | Evaluate the feasibility of applying DT in a university-based cancer centre. | Pre- and post-intervention design. | Patients with metastatic cancer in just one group (N = 10). | Before and after DT (1 month after handing DT document): 7-item cancer distress measure. BDI-II. FACIT-PAL. |

Of the 10 initial participants, 4 completed the process. No statistics were obtained. Anxiety: Baseline DT: = 2.0, SD = 1.4. Post-DT: = 3.0, SD = 2.2. Depression: Baseline DT: = 10.5, SD = 9.7. Post-DT: = 13.5, SD = 9.0. Satisfaction survey: Helpful to patient: Patient rating: = 3.3, SD = 1.0. Family rating: = 3.5, SD = 0.6. Helpful to family: Patient rating: = 3.0, SD = 2.0. Family rating: = 3.2, SD = 0.4. |

| Juliao et al.24 (2013), Portugal | To determine DT’s influence on depression symptoms and anxiety in patients with advanced disease. | RCT. | Participants with life-threatening diseases (N = 60). Sample: two groups: Intervention: DT + PSC (n = 29). Control: PSC (n = 31). |

HADS at baseline (T = 1) and on days 4 (T = 2), 15 (T = 3) and 30 (T = 4) after the intervention. |

Depression, intervention versus control: 4 days: = −4.46 (95% CI: −6.91 to −2.02; p = 0.001). 15 days: = −3.96 (95% CI = −7.33 to −0.61; p = 0.022). 30 days: = −3.33 (95% CI = −7.32 to 0.65; p = 0.097). Anxiety, intervention versus control: 4 days: = −3.96 (95% CI = −6.66 to −1.25; p = 0.005). 15 days: = −6.19 (95% CI = −10.49 to −1.88; p = 0.006). 30 days: = −5.07 (95% CI = −10.22 to 0.09; p = 0.054). |

| Montross et al.25 (2013), USA | Explore healthcare professionals’ (HP) perceptions of DT. | Transversal. | Interdisciplinary HP (N = 18). | Individual interviews: ratings to 5 questions + semi-structured questions. |

Quantitative results: DT worthwhile: = 3.83, SD = 0.39. DT reduced pain and suffering: = 3.42, SD = 0.67. DT helps the family in the future: 92%. HPs recommend DT: 100%. Qualitative results: 83% DT opportunity to share stories and lessons was a positive experience for patients. 50% DT affirmed their beliefs and values and provided meaning in life. 78% of healthcare providers thought the time it takes to do DT is an added cost. 94% believed that the time was well spent. |

| Bentley et al.26 (2014), Australia | To evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of DT for family caregivers of people with motor neuron diseases (ALS). | Pre–post test design with family caregivers of people diagnosed with ALS. | Caregivers of people with MND (N = 18). | Measure on family caregivers (at baseline and 1 week after DT): Zarit Burden Inventory. HHI. HADS. Acceptability: A family feedback questionnaire (20 items). Feasibility: family caregivers’ involvement in the therapy, time taken, protocol deviations, accommodations for the intervention and reasons for non-completion. |

Family self-reports pre–post DT: Caregiver burden: Pre: = 12.44, SD = 7.89; Post: = 16.29, SD = 11.22; p = 0.024. Anxiety: Pre: = 7.28, SD = 3.71; post: = 6.88, SD = 4.33; p = 0.257. Depression: Pre: = 4.17, SD = 3.33; post: = 4.41, SD = 3.91; p = 0.860. Hope: Pre: = 38.39, SD = 4.46; post: = 36.71, SD = 4.52; p = 0.083. Satisfaction survey: DT helpful to family member: = 4.22, SD = 0.64. DT helpful to family: = 3.33, SD = 1.08. DT documents a source of comfort in future: = 3.83, SD = 0.61. DT was helpful in reducing my feelings of stress as a carer: = 3.00, SD = 0.907. DT helped me feel closer to my family member = 2.94, SD = 0.938. Sessions to complete DT: assisted by families = 3.75 versus 4.41 alone. Days to complete intervention: assisted by families = 46 versus 39 patient alone. |

| Bentley et al.27 (2014), Australia | To assess the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of DT in enhancing end-of-life experiences for people with motor neuron disease (ALS). | Pre–post test design. | Individuals diagnosed with MND (N = 29). | Health status: ALSAQ-5. ALS-FRS. Measures at baseline and 1 week after DT: HHI. PDI. FACIT-sp-12. Acceptability: DTPFQ. Feasibility: Time taken to conduct DT, special conditions. |

DT pre–post: Hopefulness: pre-test = 38.76, SD = 5.10; post-test = 36.61, SD = 6.80; p = 0.101. PDI: pre-test = 48.59, SD = 15.45; post-test = 47.59, SD = 12.91; p = 0.504. Spirituality: pre-test = 30.72, SD = 10.43; post-test = 30.92, SD = 9.88; p = 0.936. Satisfaction survey: 92.8% DT satisfactory. 89.2% helpful to them and to family (85.2%). 84% recommend DT to other patients with ALS. Dignity related to unfinished business: MND = 3.68, SD = 0.61; DT = 3.35, SD = 1.01; SPC = 2.86, SD = 1.60. Lessened sadness o depression: MND = 3.04, SD = 3.11, SD = 1.02; SPC = 2.57, SD = 0.92. Lessened feeling of burden to others: MND = 2.96, SD = 0.92; DT = 2.81, SD = 0.98; SPC = 2.58, SD = 0.95. Increased will to live: MND = 2.96, SD = 0.98; DT = 2.94, SD = 1.11; SPC = 2.76, SD = 1.04. 3–7 therapy sessions according to specific needs. DT is feasible for people with ALS, but it is necessary to fine tune for their needs. |

| Houmann et al.28 (2014), Denmark | Study DT participation and analyse the results of its application. | Longitudinal study. | Advanced cancer patients (N = 80). | Measurements: baseline (T0), immediately after performing DT (T1), 2 weeks later (T2) when the patient had opportunity to read or share document: SISC – 6 items. PDI. EORTC QLQ-C15 PAL. HADS. PPSv2. DTPFQ – 9 items. |

Depression: T0: = 5.9, SD = 3.9; T1: difference from pre-measurement mean score = 0.6 (95% CI = −4.4 to 1.5); T2: difference from pre-measurement mean score = 2 (95% CI = −1.0 to 1.3). Patients’ sense of dignity: Depression: T0: = 1.33, SD = 1.55; T1: difference from pre-measurement mean score = −0.14 (95% CI = −0.49 to 0.21); T2: difference from pre-measurement mean score = −0.52 (95% CI = −1.01 to −0.02). Feeling of being a burden: T0: = 1.95, SD = 1.04; T1: difference from pre-measurement mean score = −0.02, (95% CI = −0.29 to 0.25); T2: difference from pre-measurement mean score = −0.26 (95% CI = −0.49 to −0.02). |

| Javaloyes et al.10 (2014), Spain | Evaluate pre–post-intervention changes in DT. | Quasi-experimental study. | Advanced cancer patients (N = 16). | HADS. EVA discomfort-well-being. Two questions about satisfaction and utility using a Likert scale. |

Pre–post DT: Anxiety: Pre: = 8.56, SD = 2.85; post: = 5.94, SD = 3.71; p = 0.010. Well-being: Pre: = 7.37, SD = 6.27; post: = 6.31, SD = 6.05; p = 0.030. Depression: Z = −1.44, p = 0.149. Serenity: Z = −1.93, p = 0.053. Wide satisfaction with DT’s content ( = 4.75) and usefulness ( = 4.43). |

| Juliao et al.29 (2014), Portugal | Determine the influence that DT has on depression and anxiety in patients with terminal illness who experience high levels of distress. | RCT. This is a continuation of the published study Juliao et al.24 (2013). |

Participants with life-threatening disease (N = 80). Intervention: DT + SPC (n = 39). Control: SPC (n = 41). |

HADS at baseline (T = 1) and on day 4 (T = 2), day 15 (T = 3) and day 30 (T = 4) after the therapy. |

Depression intervention versus control: T2: = −4.00 (95% CI: −6.00 to −2.00; p < 0.001). T3: = −4.00 (95% CI = −7.00 to −1.00, p = 0.010). T4: = −5.00 (95% CI = −8.00 to −1.00, p = 0.043). Anxiety intervention versus control: T2: = −3.00 (95% CI = 5.00 to −1.00, p < 0.001). T3: = −4.00 (95% CI = −7.00 to −2.00, p = 0.001). T4: = −4.00 (95% CI = −7.00 to −1.00, p = 0.013). |

| Vergo et al.30 (2014), USA | Assess the feasibility of DT relatively early in the disease trajectory and the effect on accepting death, distress, symptoms, quality of life, peacefulness and advanced care planning. | Cross-sectional one group pre–post test design. | Patients with stage-IV colorectal cancer receiving palliative chemotherapy (N = 15). | Likert. TIA. ESAS. Distress thermometer. 2-item QoL Scale. H-CAP-S. DTPFQ-5 items. |

Satisfaction survey: 100% satisfied with DT. 88% DT helpful. 88% increased their sense of meaning. 78%increased their sense of meaning. 88% thought it was helpful to their family. 78% DT increased sense of dignity and purpose. 67% DT increased their will to live. No changes in physical and emotional symptoms (n = 9). |

| Aoun et al.31 (2015), Australia | To assess the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of DT for reducing distress in people with MND and their family caregivers. | Pre- and post-intervention design. n = 27 patients and n = 18 caregivers. |

Participants recruited from the MND Association of Western Australia. 35 clients, 27 patients completed the study; 18 family member caregivers participated. |

Post-testing 1 week after DT through questionnaire. Feasibility: number of visits by therapist, number of days to complete the therapy, time taken by therapist to deliver the therapy. Acceptability: Participants’ views on whether DT helped them or their families. Patient feedback: QOL, spiritual well-being, sense of control of one’s own life, feeling more respected and understood. Caregiver feedback: Effectiveness outcomes: PDI. ALSAQ-5. FACIT-sp-12. HHI. ZBI-12. HADS. |

Patients: PDI: Pre: = 49.82, SD = 15.72; post: = 49.14, SD = 12.83; p = 0.67. Hope: Pre: = 38.60, SD = 5.13; post: = 36.76, SD = 6.54; p = 0.20. Spiritual well-being: Pre: = 30.76, SD = 10.08; post: = 31.04, SD = 9.62; p = 0.82. QoL: Pre: = 9.44, SD = 3.89; post: = 9.28, SD = 3.77; p = 0.73. Family member caregivers: Caregiver burden: Pre: = 12.76, SD = 8.01; post: = 16.29, SD = 11.22; p = 0.055. Hope: Pre: = 38.35, SD = 4.59; post: = 36.71, SD = 4.52; p = 0.10. Anxiety: Pre: = 7.53, SD = 3.65; post: = 6.88, SD = 4.32; p = 0.25. Depression: Pre: = 4.35, SD = 3.33; post: = 4.41, SD = 3.90; p = 0.90. 89% DT helpful for me (patient) and 81% useful for my family. |

| Johnston et al.32 (2016), UK | Assess feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of DT. | Mixed-method study. | 27 participants. 7 patients with early-state dementia (ESD), 7 family members, 7 stakeholder and 6 focus group members. |

DT summaries. Post-DT interviews. Focus group data. Stakeholders interview. Outcomes measures: HHI, PDI, QoL. |

Patients had no problems to complete the therapy on their own. Patients very open about emotions, reactions and family situation. They trusted and felt comfortable sharing their life experiences. All participants found DT beneficial and DT document accurate. Overarching themes for DT: a life in context, a key to connect, personal legacy. Participants felt that DT would be of benefit in future years, helping family or carers to connect better with the person and act as a reminder. Families interested in earlier parts of patients’ lives that they were previously unaware of. Perceived problems relating to issues that might affect dignity were generally low. |

| Lindqvist et al.34 (2015), Sweden | Analyse the experience of participating in DT. | Qualitative study. | 8 patients. | Interview. | ( = 14 survival days after DT). Staff considered DT unsuitable for 52/62 patients due to rapid degeneration, frailty or cognitive impairment. Some candidates considered DT: superfluous to immediate needs, physically and emotionally unbearable, DT questions too pretentious for them. Therapist reflection: she may inadvertently steered patient away from her own objectives in forming her legacy. Little adherence to therapy and difficulties in its implementation due to the cultural context. |

| Juliao et al.33 (2015), Portugal | Determine whether DT offers a survival advantage to standard palliative care (SPC). | RCT. This is a part of the published study Juliao et al.29 (2014). |

80 participants. DT + SPC intervention n = 39; SPC control n = 41. |

Pre-intervention: HADS. PPS. MMSE. Post-intervention: Survival time. |

Survival for DT: 26.1 days (95% CI: 23.2–20.0). Survival control group: 20.8 days (95% CI: 17.4–24.2); survival hazard ratio for DT group: 0.35 (95% CI = 0.13–092). |

| Rudilla et al.11 (2016), Spain | Analyse the effects of DT and counselling in home care patients. | Pilot RCT. | Palliative home care patients (N = 70). | Pre–post intervention: PDI. HADS. BRCS. GES Questionnaire. Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Questionnaire. EORTC-QLQ-C30 (2 items). |

Peace of mind: Pre-DT: = 2.52, SD = 0.75; post-DT: = 1.76, SD = 0.58, p < 0.001. QoL: Pre-DT: = 3.31, SD = 1.50; post-DT: = 4.07, SD = 21.17, p = 0.011. Depression: Pre-DT: = 11.54, SD = 2.40; post-DT: = 13.11, SD = 1.77, p = 0.001. |

DT: dignity therapy; RCT: randomized controlled trial (methodology); ALSAQ-5: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Assessment Questionnaire-5; ALS-FRS-R5: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale–Revised-5; BRCS: Brief Resilient Coping Scale; Duke-UNC-11: Functional Social Support Questionnaire; EORTC-QLQ-C30: EORTC Quality of Life C30 Questionnaire; DTPFQ: Dignity Therapy Patient Feedback Questionnaire; EVA: Visual Analog Scale; ESAS: Edmonton System Assessment Scale; FACIT-PAL: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Palliative Care; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; GES: General Emergency Services (GES questionnaire of spirituality); HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; H-CAP-S: Hypothetical Advanced Care Planning Scenario; HHI: Herth Hope Index; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; PDI: Patient Dignity Inventory; PPSv2: Palliative Performance Scale Version 2; PSC: Palliative Standard Care; PUBS: Purposelessness, Under-stimulation and Boredom Scale; QoL: quality of life; SISC: Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns; ZBI-12: Zarit Burden Interview-12; ZSDS: Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; CH: control nursing home; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; TIA: terminal illness acknowledgement.

Another randomized clinical trial aimed to assess DT’s potential effectiveness in reducing distress in advanced cancer patients (n = 45) referred to PC teams.16 While no part of the DT protocol, this study included interest in dignity as an entry criteria for patients offered DT. The intervention group received DT and standard PC (n = 22) and the control group standard PC alone (n = 23).

Different outcomes were evaluated at the baseline and 1 and 4 weeks after the ‘generativity’ document was delivered: PDI, the Herth Hope Index (HHI) for measuring sense of hope, HADS, EQ-5D and a satisfaction questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life and satisfaction with quality of life. No significant differences were identified on the PDI between groups at any time point; observing in the control group an improvement in dignity-related stress along the follow-up compared with baseline data. In the intervention group, there was a slight improvement in the first week which was not maintained at fourth week16 (Table 2). Regarding hope, the control group observed a decrease during the follow-up, and the intervention group observed an improvement at weeks 1 and 4, compared with baseline data.16

A randomized clinical trial was conducted with 60 elderly patients in nursing homes.19 The intervention group was treated with DT (n = 31) and the control group with standard psychosocial care group (n = 29). The following measures were assessed in both groups at the baseline and at weeks 1 and 8: PDI, Geriatric Depression Scale (Short Form), HHI and Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. Baseline data measured by the PDI showed low distress levels related to dignity; hopefulness and quality-of-life levels were high. In both groups, PDI score increased after 1 week and decreased at week 8 and hopefulness and quality-of-life levels were high. No significant differences between the intervention and control groups were found on the evaluation timeline19 (Table 2).

In Portugal, 80 terminal patients were randomized to an intervention group receiving DT plus standard PC (n = 39) and into a control group receiving only standard palliative care (SPC) (n = 41).29 The HADS showed that patients had a high level of distress at baseline (T1; HADS depression > 11 in both groups), and it was measured also 4, 15 and 30 days after the end of DT (T2, T3 and T4, respectively). The preliminary results with 60 patients (DT, n = 29; PC, n = 31)24 found decrease in depressive symptoms in the DT group after 4 days compared with baseline data and 15 days, but not at 30 days (Table 2). They also found a significant decrease in anxiety according to the various measures.24 In a later publication with the results of 80 patients (DT, n = 39; SPC, n = 41), while the DT group always showed better scores than at baseline for both depression and anxiety, the control group always showed worse scores than at baseline. The differences at follow-up (4, 15 and 30 days) between DT and control groups were statistically significant29 (Table 2). In a secondary analysis, they studied whether DT offered a significantly higher survival compared to SPC. The survival time for DT group was higher (26.1 vs 20.8 days)33 (Table 2).

The most recent pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) was carried out in Spain at a home care unit with 64 patients assigned to two therapy groups: DT (n = 32) and counselling (C) (n = 32), although limited information is provided regarding how the therapies were conducted.11 The measurement instruments employed were PDI, HADS, Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS), GES Questionnaire of spirituality, Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Questionnaire and 2 items of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 of quality of life. They report statistically significant differences with respect to the dimensions of dignity, anxiety, spirituality and QoL comparing pre–post data within DT group. The data provided for counselling group compare the post-counselling with DT group’s baseline data so the comparison is not meaningful. Depression increased significantly in the DT group after the intervention, and there were no differences with respect to resilience. They also calculated the differences between groups post intervention and found statistically significant differences in anxiety, with lower scores in the counselling group DT versus counselling (Table 2). However, there is no comparison about the magnitude of the effect among the interventions.

Nonrandomized studies

In Canada, a non-randomized study was conducted to evaluate DT’s impact on psychosocial and existential distress (n = 100).13 Distress was assessed using the Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns (SISC) – a tool measuring depression, dignity, anxiety, pain, hope, desire to die, suicide and well-being. This also included the ESAS and 2 items to measure quality of life and a scale measuring will to live. They evaluated these pre- and post-DT aspects. In addition, a satisfaction questionnaire was used to assess participants’ perception of DT.

The suffering measure showed significant improvement post intervention, as well as self-reported depression (Table 2). No significant changes were found in scores of despair, wanting to die, anxiety and suicide. They found that family support correlated positively and moderately with meaning in life and sense of direction and weakly with sense of suffering and will to live. Patients who reported greater initial psychosocial distress benefited from therapy, which was reflected in weak correlations with quality of life, satisfaction of quality of life and desire for death13 (Table 2).

Two pre- and post studies have evaluated DT’s effectiveness with patients suffering from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).27,31 The first one was conducted with 29 patients assessing the following aspects at baseline and 1 week after completing the DT: HHI, FACIT-sp, PDI, ALS Assessment Questionnaire and ALS Cognitive Behavioural Screen. They were also sent a 25-item questionnaire to explore DT’s suitability, adding three items about hope and social support (5-point Likert scale). At baseline, the group was hopeful, but experienced low-dignity-related distress and seemed to feel that their spiritual well-being was low. No significant changes in hope, dignity and spirituality between the pre- and post-intervention assessments were found27 (Table 2), but participants and families considered DT was very helpful.

The second study was conducted with motor neuron disease (MND) patients (n = 27) and their families (n = 18).31 The PDI, QoL, FACIT-sp, HHI, HADS for family members and Zarit for the caregiver were administrated pre–post DT (1 week after handing the DT document). In this study, no significant changes were found before and after DT on measures of dignity-related distress, or in quality of life, spiritual well-being or hope (Table 2). No differences in measures related to caregiver burden, anxiety depression or hope were found,31 but participants reported DT was helpful for them and their families, as in other studies.27

A quasi-experimental study with data on the impact of DT on advanced cancer patients was carried out in Spain (n = 16). Patients’ discomfort and suffering were assessed by HADS and visual analogic scales of well-being and suffering at the baseline and 1 week after, as well as some questions about satisfaction and usefulness. The results show a statistically significant difference in the anxiety and well-being. However, there was no statistically significant difference for depression and serenity10 (Table 2).

Satisfaction, suitability and feasibility of DT

Patients’ general satisfaction with DT

In 2005, Chochinov et al.13 carried out a DT satisfaction survey, assessed with a 0- to 7-point ordinal scale, in 100 hospice patients. Most of the patients were satisfied (⩾4 points; 91%) with DT. The majority considered it useful or very useful and helpful for them and their families. More than half said it increased their sense of dignity, hope, and their sense of purpose. In all, 47% of participants indicated that DT increased their desire to live13 (Table 2).

Later Chochinov study results are along the same lines. Patients participating in the first (RCT on DT (n = 441) showed improvements in perception on various dimensions of end-of-life experience.15 The DT group found the intervention more helpful and had improved perceptions on quality of life, sense of dignity and perceptions of sadness or depression improved. Perceived improvements concerning quality of life and sense of dignity were greater and statistically significant in the DT group. In addition, patients reported that it also changed how their families saw and appreciated them and that it was useful for the family. Patients perceived DT was also significantly better than PC at reducing sadness or depression15 (Table 2).

In another RCT on DT,16 patients in the intervention group were more positive than the control group on all the scores related to self-perceived benefits after 4 weeks: help received, greater sense of purpose, although greater meaning in life, and family support were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Subsequent studies have further examined participants’ satisfaction using more qualitative approaches. In one case study,21 three PC patients with high levels of dignity-related distress were chosen as cases. The patients believed that DT was useful for them and would be so for their families. Levels of dignity-related distress increased in two patients 4 weeks after the therapy, but not in the third; but scores always remained lower than at baseline (Table 2); as it remained below the baseline level, the patients continued to believe that DT had been worthwhile. Along those lines, the three patients reported aspects such as DT helping to become aware that his life has not always been a life of illness and disability, allowing to accept limitations and providing opportunities to explore feelings and fears and reveal suffering to family members (Table 2).

Another study,22 which compares elderly participants’ perceptions in a DT (n = 25) and control group (n = 24), revealed differences and similarities (Table 2). Some participants considered the legacy document useful and it made them feel important, while other comments were quite neutral. Others felt that the legacy document opened up their family history, reviewing positive aspects of their lives and sharing their stories and would help to be remembered after they died. Participants appreciated their interaction with the therapist as a positive change in their daily routine after the DT. Neither group thought that it had helped them with their problems related to coping with loss and distress symptoms22 (Table 2).

In a similar study with cancer patients who were being treated with PC, similarities and differences between the control (n = 23) and DT (n = 22) groups were also found.23 The legacy document was identified as an opportunity to feel that their life was worthwhile and say things that they could not say in person. In both groups, patients reported feeling more positive and motivated to do things. They also mentioned the interviewer and therapist’s abilities in that they made them feel good. In addition, in both groups, but more so in the DT group, they noted that they had reviewed their life and improved communication with their families and that it had influenced their personal relationships23 (Table 2).

Regarding possible distress caused by the therapy or research, many participants described positive experiences regarding their participation. Nobody mentioned being particularly distressed, but some showed a bit of concern with the content of their legacy document and the recipients’ possible reactions to it.23 The presence of these concerns raises the question of how DT was applied, as the protocol includes helping directly patients so that they shape their document in a way that will not cause them distress or problems or inflict harm to recipients of the document. In a small sample of terminally ill patients (n = 4), compared to baseline, post-intervention mean depression and anxiety scores increased (Table 2). However, the majority of patients believed that the therapy had been helpful to them and their families.9 Another study confirms patient’s positive perception of DT in patients with colorectal cancer.30 More than two-thirds of the participants (n = 15) reported that DT was helpful and increased their sense of meaning, sense of dignity and purpose and their will to live30 (Table 2).

Families’ general satisfaction with DT

One study asked family members retrospectively (n = 60) about their perceptions of DT’s impact.7 The vast majority considered that it had helped the patient. More than two-thirds believed that the patient’s perception of dignity and meaning in life had increased and more than half that the therapy had helped the patient in preparing for death and emphasized the importance of implementing this therapy as part of care (Table 2). In all, 43% said DT reduced their loved one’s suffering.7 Similarly, in a recent study, 89% of families said the therapy was helpful for patients with ALS.31

A qualitative study carried out in Canada in 24 relatives pointed that DT was believed helpful to their loved ones, and more than half felt that it was an important component of their loved ones’ care18 (Table 2). They also stated that DT gave them the opportunity to discuss their feelings and reflect on their lives.18 In another study, the families of the elderly saw DT positively and they mentioned that the interaction with the therapist was valuable for their elderly family member by providing them company and helping them assesses their life positively. In addition, family members highlighted that DT offers the opportunity to communicate and get to know new parts of their lives.20

As for the therapy’s influence on the family, no significant results in terms of burnout syndrome, anxiety, depression or an increase in hope are available in the two identified studies measuring DT’s impact on the family using pre–post measurements26,31 (Table 2). However, relatives of ALS patients appreciated DT and felt that it would help them during the grieving period26 (Table 2).

The studies coincide in showing that family members feel that DT helps them7,9,20 (Table 2). In several studies, about 70% of families mentioned that the legacy document will be of great help to them both at present and in the future.7,26,31 At the same time, some relatives wonder about the possible negative impact of the legacy document,7,20 depending on the family’s level of acceptance regarding the patient’s death or on the present relationship between the patient and his/her relatives.26 This underscores why therapists must be skilled in helping patients navigate through DT, hence mitigating possible negative consequences of generativity documents on recipients.

Families recommend DT to other patients and their families in the same situation, ranging from 70%31 to 95%.7 Other study shows how the 33.3% of families noted that their stress was reduced and hopes raised, 50% reported that it was useful in facing death, and 72% agreed that DT is and will remain a source of comfort for them.7,31

Professionals’ satisfaction regarding DT

Health professionals’ perceptions regarding DT have been assessed in some articles, including the views of physicians, nurses, social workers, psychiatrics and chaplains.

In a qualitative study with 18 PC professionals, they considered DT worthwhile because it reduced the patient’s pain and suffering.25 In addition, the majority of professionals felt that it would be helpful for the patient’s family in the future and suggested therapy to patients because they thought that it helped them to reflect on their lives and share stories and lessons (Table 2). In all, 50% of professionals believed DT reaffirmed patients’ beliefs and values and gave them meaning in life; they also thought it would help their suffering related to dignity and prepare them for the future.25 Regarding the influence that the therapy had on professionals, they were able to get to know patients who allowed them to read their legacy documents better and to be more in tune with them, increasing their job satisfaction.25 Professionals held that DT had a positive effect on how they provided care and how they assessed the patient and had helped them to better understand the patient18 (Table 2).

Suitability of DT

Studies report high participating rates (>80%)13,17 and low dropout rate (22%).13 Only a Japanese study reports low participating rates (14%).8 In fact, those who refused to participate were concerned that it would make them think about death and wondered why it was offered to them while they were dying.8 This raise questions about how DT was presented, as DT has been done with non-terminal populations and in those context is presented as an opportunity for reminiscence and personal reflection. DT must always be offered in a way that respects the patient’s healthy defences and is mindful of their degree of acceptance regarding their prognosis8 (Table 2).

Several studies have analysed the suitability of DT by measuring whether participants consider it useful or helpful.16,19,26,27,31 One study showed that cancer patients who received DT perceived that they were more supported than those receiving standard care, as well as had more purpose in their lives16 (Table 2). In a qualitative study in patients with ALS (n = 29), the vast majority of them considered the DT satisfactory or helpful. They reported greater benefits in the areas of dignity related to unfinished business, but less in feeling like a burden, increase in will to live and decrease in sadness or depression. The majority considered it useful for their family and would recommend it to other ALS patients27 (Table 2). ALS patients’ relatives identified positive impacts of DT on the patient regarding themselves, and more relatives transmitted that DT was helpful to them (n = 9), but some did not (n = 4). Relatives reported greater benefits in the areas of DT legacy as a source of comfort for them, but less in reducing their feelings of stress as a carer or helping feel closer to their partner.26

A Swedish study analyses the suitability of DT considering data and reflections from professionals involved in its development with eight patients.34 Professionals believe that many patients are not suited for DT because their health deteriorates so rapidly and because of frailty or cognitive impairment. Professionals also pondered the lack of clarity on what kind of patient could most benefit from therapy. In addition, some patients (n = 11) refused therapy because they considered it largely ineffective for immediate needs or because they saw it as difficult to physically or emotionally sustain. The retrospective analysis of the data suggests that they may have overzealously followed the DT question framework and at times inadvertently steered away the patient from her own objectives in forming her legacy,34 which raise questions about therapist’s preparation to conduct DT.

Feasibility of DT

Some studies consider the influence that the patient’s cognitive or physical condition has during the course of therapy on DT feasibility. In a Canadian study with elderly patients, the results regarding DT were positive,18 more than half of patients accepting to participate. In other study, it was expected to systematically recruit patients to DT among those enrolled in the specialized palliative home care service, but this resulted less feasible than expected. Staff deemed DT unsuitable for 52 of 62 patients due to patients’ deterioration, frailty and cognitive impairment. Besides, 11 of the 19 patients who were directly approached choose not to participate.34 In a study conducted with patients with early-state dementia, participants did not have difficulties to recollect minute details from the past although it is mentioned the need for the time between meetings to be fairly short to help with memory.32

In addition, a study of ALS patients living with their families in metropolitan and rural areas in Australia lists aspects that need to be considered when calculating the costs necessary for the completion of this therapy (medical training, interviews, document editing and getting to and from appointments). Considering these aspects on their experience, they say that therapy is unfeasible in small organizations with limited resources, although still feasible in larger places.31

Another study of patients treated with PC services provides the economic cost of DT and argues that the cost is reasonable and profitable for the organization17 (Table 2). Thus, a majority of healthcare professionals believed that despite the added cost, the expense was worthwhile.25 Finally, there was a study on DT’s feasibility via telemedicine. In the study, they concluded that telemedical DT is feasible because the problems that appeared were easily solved12 (Table 2).

Adapting to other cultures and populations

DT has been largely explored in the Anglo-Saxon contexts of the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. In studies on adapting the therapy to other cultures, some have noted cultural influences that may require an adaptation on the way that the therapy is offered.8,28,34 Such differences do not mean that the therapy is not applicable, but rather that it needs some adjustments in its application.28

On the one hand, different cultures interpret and accept certain words differently. There are terms that can be misinterpreted, such as ‘alive’, ‘more alive’, ‘still’ and ‘future’ and others, such as ‘proud of’, are just inappropriate in some cultures.14 Some of these words, for example, ‘proud of’, can be revised to ‘happy with’,14 to avoid conflict with cultural traits of modesty and privacy.28 Some reactions suggest that confrontations exist between the participants’ norms and values at the cultural, hierarchical and individual levels.34 On the other hand, the way that a population faces terminal condition can in itself be an obstacle for adapting the therapy because in the Japanese population, being ‘unaware of death’ is considered culturally appropriate. If participating in DT is offered in a way that confronts them with death and dying, it is likely to be rejected.35 So, creating a legacy is not something patients hope for, as they avoid talking about their situation.8

There are studies that show DT’s adaptability among populations other than cancer, including the elderly population,20,25 cognitively impaired patients;18 patients with ALS26,27,31 and patients with early-state dementia.32 Elderly participants indicated that DT positively impacts their experience during their final days, and that of their families, and would recommend it to other families.18,20 However, difficulties with patients’ cognition levels were seen; since DT requires memory, many patients relied on help from their families.18,20 In this case, DT was adapted to use family members as proxy informants. In response, researches have proposed amending the protocol in cases where the family participates20 and continuing to study the feasibility of the therapy in the elderly population.18

On the other hand, studies about DT’s suitability for ALS patients have been conducted.26,27,31 DT was administered in this case with family support. There, family accompanied patients during sessions and participated when the patient requested help. The studies conclude that DT is suitable and beneficial and, therefore, can be adapted to such patients. However, these two studies26,27 referred to communication difficulties and the increased time the sessions required since family presence made them longer. The number of sessions required to complete the DT was lower in the group assisted by their family26 (Table 2).

Discussion

There are five randomized control trials, and the results are not conclusive about the effect of DT on anxiety, depression, well-being, distress related to patient’s dignity, hope, quality of life and symptoms. Two randomized control trials have been conducted with patients with high levels of baseline psychological distress.11,29 One showed statistically significant decrease on patients’ anxiety and depression scores measured at 4, 15 and 30 days, compared with baseline scores.29 The other comparing measurements pre–post DT showed statistical decrease in anxiety scores but not in depression.11 Regarding randomised control trials with patients with low base levels of distress, measures of depression, distress or hope improved, albeit not significantly. Non-randomized studies reported statistically significant improvements on existential and psychosocial measurements, such as suffering and depression;13,25 except for one study that reported increases in depression and anxiety scores, based on information from four patients9 (Table 2).

Studies that did not obtain significant results provide a variety of possible explanations.12,15,16,24,28,31 On the one hand, there is reference to the absence of a specific instrument to measure the effectiveness of DT in the literature.36 The disease’s progression may also influence the perception of the therapy’s effectiveness. As patients deteriorate, they may start to feel worse, and thus, their perception of DT’s effectiveness may not endure.13

On the other hand, sampling patients with low levels of distress may be the reason why studies show little impact from DT, given there is little room for improvement, that is, floor effects. Recent studies suggest the idea that patients with higher levels of distress may obtain more benefit from DT11,29 than those with low levels.

The overall results on effectiveness are in line with a recently published review about DT based on one database search including DT studies conducted with different types of patients,37 not just patients with life-threating advanced illnesses. They considered the primary results of DT on patients. However, the current review has included recent RCTs and also families and health professionals’ perspectives and has carried out a critical analysis. As several authors mention, DT’s effect might be multidimensional and other possible effects of therapy should be assessed. Thus, a comprehensive view is needed. This idea is consistent with other studies that indicate that patients, families and healthcare professionals report that DT heightens a sense of dignity, hope and sense of purpose and helps them to know the person better13,16,22,30 (Table 2). They also report that it is useful for their families and offers opportunities to share things.23

Relatives considered that DT helped their loved one and increased their perception of dignity and meaning in life and decreased suffering.31 Family members highlighted the opportunity DT offers to communicate and get to know new parts of their lives.20

The legacy document is especially relevant for both the patient and his family and for professional caregivers. Patients and relatives suggest that DT and the legacy document help them to share and make sense of things and also suggest that it will be useful when the family is mourning. In turn, healthcare professionals note that reading the patient’s legacy document helps them better understand the person they are caring for, has a positive effect on how they provide care as well as on how they assess the patient and it increases their satisfaction at work.18,25 However, some also suggest the necessity of taking into account the family situation, its relationship and dynamics so that DT does not negatively impact those.26 The protocol in fact provides clear directions on how family distress can be mitigated by taking steps to address any content that could provoke it.38

This review includes information about adaptations of DT to patients with different pathologies and in different cultural contexts for where it was originally developed. Regarding the study’s acceptability and feasibility, DT is seen in a positive light, but there are challenges in applying the therapy to patients with cognitive impairment,18,34 fragile patients34 or people with ALS.27 Studies have adapted the protocol and encouraged relatives’ participation in these cases. However, in the future, it is important to identify which patients are most suitable for DT and to pinpoint adaptations needed for using DT in other populations.

DT adaptation studies show that this therapy is applicable in different cultural contexts and in different locations and types of patients,14,18,25,27,31 with small protocol changes. For example, sometimes there are words, phrases or concepts that are inappropriate to the context and should be reconsidered.8,14,34 We should not forget that the question framework is meant to guide the direction that the conversation takes; which is why flexibility is so embedded within DT protocol and should be considered when adapting it in different contexts.

There are few publications on effective psychological interventions during PC treatment and those in circulation are limited to very specific issues, while others are too complex to apply clinically, which sometimes limits their usefulness for patients facing death with advanced disease and multiple symptoms. DT is a simple intervention that recognizes an individual’s need to have closure and improve communication with loved ones.37 Based on the evidence, DT should be offered as a choice to patients with life-threatening diseases and explore more deeply DT effect on patients and their families.

Future research should aim to define the characteristics that make patients suitable for DT, focusing on identifying those who would benefit most from it. Further studies are necessary in patients with high levels of distress and to assess whether it is possible to demonstrate DT’s effectiveness in these patients. These studies should present sample size and statistical power calculations and explain clearly the randomisation process and who conducts the DT and how.

It is also advisable to study ways of measuring DT’s effectiveness since the available instruments do not seem to effectively capture the intervention’s outcomes, especially given that interviews with patients and families frequently reveal high levels of satisfaction and a sense that the therapy is useful and effective.

Limitations

One limitation found in this review is related to the possibility of publication bias since there is a tendency not to publish unfavourable data. In psychological interventions, not being able to find significant data or differences is common for various reasons, such as a lack of specific instruments to measure an intervention’s effectiveness which may affect effect size, the heterogeneity of groups or the beneficial nature of the therapist–patient relationship itself, which can make it difficult to pinpoint what exactly has been effective. On the other hand, data extraction was difficult in some articles since the text and tables did not display all quantitative information. In this sense, in spite of the good data collected, more detailed methodological information is required in some of the articles identified (e.g. sample size calculations, statistical power and theoretical framework for analysis in qualitative studies) in order to facilitate the interpretation of the results. This should be taken into account when developing future studies on DT. Furthermore, more in-depth analysis such as multivariable analysis could be done in order to identify factors that might influence the effect of DT. The lack of homogeneity presenting the data complicates the comparison between studies; more homogeneity could facilitate new studies comparing populations, for example, through meta-analysis which could contribute to improve the evidence in the field.

It is noteworthy that majority of the studies do not provide detailed information about how DT was conducted and therapists’ skills. Most articles include directly Chochinov’s protocol reference with no additional information about how it was conducted, preventing an assessment of DT protocol application which might influence the results.

Strengths

In this comprehensive systematic review of DT’s implementation with patients suffering from a life-threatening disease, we have reviewed all the results obtained from all DT studies meeting our defined quality threshold criteria. The articles have been assessed according to methodological issues and these have been considered when writing the results. Methodological shortcomings have been identified and reported in this comprehensive review.

The review includes an integrated and comprehensive view of the therapy, analysing efficiency, effectiveness, acceptability and feasibility, family members’ perceptions, as well as those of healthcare professionals, and the therapy’s adaptability to different populations and cultures.

Conclusion

The available evidence suggests that DT is beneficial. Patients and families evaluate it positively, suggesting that it has a variety of effects and can go beyond traditionally considered variables (e.g. anxiety or depression). The results suggest that patients with the highest distress levels can benefit the most from therapy, but more studies are needed to confirm DT’s outcomes. DT can be adapted to different populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Chochinov for his continued support throughout the development of this article, especially in giving references, reviewing it and offering helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. LeMay K, Wilson KG. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28: 472–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care-a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA 2002; 287: 2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007; 335: 184–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide, SA, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015, http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf (accessed 7 May–June 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP checklists. Oxford: CASP, 2014, http://www.casp-uk.net/ (accessed 30 June 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7. McClement S, Chochinov HM, Hack T, et al. Dignity therapy: family member perspectives. J Palliat Med 2007; 10: 1076–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akechi T, Akazawa T, Komori Y, et al. Dignity therapy: preliminary cross-cultural findings regarding implementation among Japanese advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 768–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johns SA. Translating dignity therapy into practice: effects and lessons learned. Omega (Westport) 2013; 67: 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Javaloyes N, Botella L, Meléndez V, et al. Aplicación de la Dignity Therapy en pacientes oncológico en situación avanzada. Psicooncología 2014; 11: 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudilla D, Galiana L, Oliver A, et al. Comparing counseling and dignity therapies in home care patients: a pilot study. Palliat Support Care 2016; 14: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Leibee S, et al. A feasibility study of dignity psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2(2): 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5520–5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Houmann LJ, Rydahl-Hansen S, Chochinov HM, et al. Testing the feasibility of the dignity therapy interview: adaptation for the Danish culture. BMC Palliat Care 2010; 9: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, et al. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Montross L, Winters KD, Irwin SA. Dignity therapy implementation in a community-based hospice setting. J Palliat Med 2011; 14: 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chochinov HM, Cann B, Cullihall K, et al. Dignity therapy: a feasibility study of elders in long-term care. Palliat Support Care 2012; 10: 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a phase II randomized controlled trial of a brief palliative care psychotherapy. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goddard C, Speck P, Martin P, et al. Dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a qualitative study of the views of residents and recipients of ‘generativity’ documents. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall S, Goddard C, Martin P, et al. Exploring the impact of dignity therapy on distressed patients with advanced cancer: three case studies. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 1748–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hall S, Goddard C, Speck P, et al. It makes me feel that I’m still relevant’: a qualitative study of the views of nursing home residents on dignity therapy and taking part in a phase II randomised controlled trial of a palliative care psychotherapy. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall S, Goddard C, Speck PW, et al. ‘It makes you feel that somebody is out there caring’: a qualitative study of intervention and control participants’ perceptions of the benefits of taking part in an evaluation of dignity therapy for people with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45: 712–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Juliao M, Barbosa A, Oliveira F, et al. Efficacy of dignity therapy for depression and anxiety in terminally ill patients: early results of a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Support Care 2013; 11: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Montross LP, Meier EA, De Cervantes-Monteith K, et al. Hospice staff perspectives on dignity therapy. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 1118–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bentley B, O’Connor M, Breen LJ, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bentley B, O’Connor M, Kane R, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(5): e96888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Houmann LJ, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of dignity therapy in advanced cancer patients admitted to palliative care. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Juliao M, Oliveira F, Nunes B, et al. Efficacy of dignity therapy on depression and anxiety in Portuguese terminally ill patients: a phase II randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vergo MT, Nimeiri H, Mulcahy M, et al. A feasibility study of dignity therapy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer actively receiving second-line chemotherapy. J Community Support Oncol 2014; 12: 446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoun SM, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ. Dignity therapy for people with motor neuron disease and their family caregivers: a feasibility study. J Palliat Med 2015; 18: 31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnston B, Lawton S, McCaw C, et al. Living well with dementia: enhancing dignity and quality of life, using a novel intervention, Dignity Therapy. Int J Older People Nurs 2016; 11: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Juliao M, Nunes B, Barbosa A. Dignity therapy and its effect on the survival of terminally ill Portuguese patients. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84: 57–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lindqvist O, Threlkeld G, Street AF, et al. Reflections on using biographical approaches in end-of-life care: dignity therapy as example. Qual Health Res 2015; 25: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, et al. Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol 2007; 18: 1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nekolaichuk CL. Dignity therapy for patients who are terminally ill. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12(8): 712–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, et al. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chochinov HM. Dignity therapy: final words for final days. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]