Abstract

Background

Migraine prevention guidelines recommend oral prophylactic medications for patients with frequent headache. This study examined oral migraine preventive medication (OMPM) treatment patterns by evaluating medication persistence, switching, and re-initiation in patients with chronic migraine (CM).

Methods

A retrospective US claims analysis (Truven Health MarketScan® Databases) evaluated patients ≥18 years old diagnosed with CM who had initiated an OMPM between 1 January, 2008 and 30 September, 2012. Treatment persistence was measured at six and 12 months’ follow-up. Time-to-discontinuation was assessed for each OMPM and compared using Cox regression models. Among those who discontinued, the proportion that switched OMPMs within 60 days or re-initiated treatment between 61 to 365 days, and their associated persistence rates, were also assessed.

Results

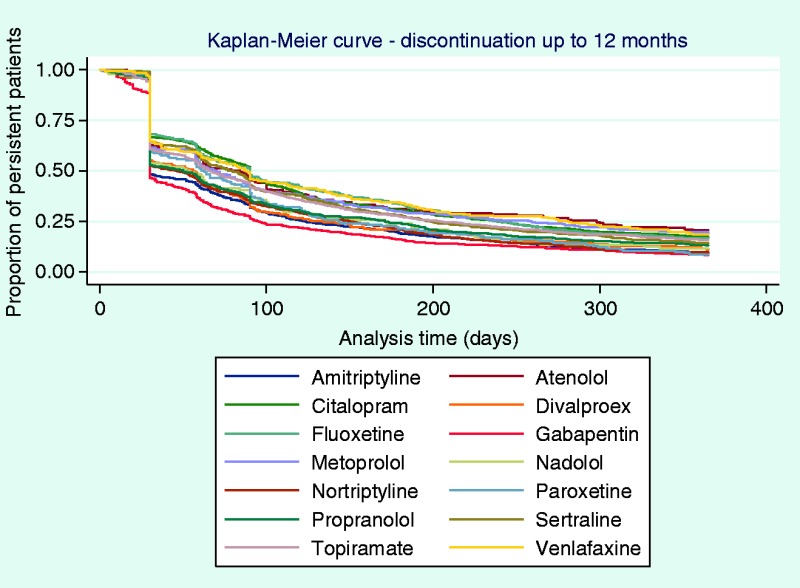

A total of 8707 patients met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Persistence to the initial OMPM was 25% at six months and 14% at 12 months. Based on Kaplan-Meier curves, a sharp decline of patients discontinuing was observed by 30 days, and approximately half discontinued by 60 days. Similar trends in time-to-discontinuation were seen following the second or third OMPM. Amitriptyline, gabapentin, and nortriptyline had significantly higher likelihood of non-persistence compared with topiramate. Among patients who discontinued, 23% switched to another prophylactic and 41% re-initiated therapy within one year. Among patients who switched, persistence was between 10 to 13% and among re-initiated patients, persistence was between 4 to 8% at 12 months.

Conclusions

Persistence to OMPMs is poor at six months and declines further by 12 months. Switching between OMPMs is common, but results indicate that persistence worsens as patients cycle through various OMPMs.

Keywords: Persistence, medication, migraine disorders/epidemiology, migraine disorders/prevention and control, patient compliance/statistics and numerical data, retrospective studies

Introduction

The definition of chronic migraine (CM) has been updated with the third edition (beta version) of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, and is described as headaches that occur on ≥15 days per month with ≥8 days per month meeting criteria for migraine and/or for which a migraine-specific medication was used (e.g., triptans or ergot) for >3 months (1). General migraine, often referred to as episodic migraine (EM), is characterized by the presence of migraine with <15 headache days per month. Chronic migraine is a highly burdensome disorder that has been shown to significantly lower quality of life, and leaves many patients unable to perform daily activities (2–6). Patients with CM also use significantly more resources, including increased healthcare provider visits, emergency department visits, and diagnostic testing (3,5,6). Chronic migraine is three times more common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55, ranging from 1.4 to 2.2% among adults worldwide (7,8).

Guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society for the prevention of EM recommend that patients with frequent debilitating headaches start pharmacological treatments with oral migraine preventive medications (OMPMs). Treatment with propranolol, timolol, amitriptyline, divalproex, or topiramate is suggested as being most efficacious (9). Although clinical trial results have demonstrated that these medications are efficacious for migraine prevention in patients with EM, only topiramate has been studied for migraine prevention in patients with CM in randomized clinical trials (10,11). Further, real-world analyses using a variety of observational methods have revealed that adherence and persistence to these medications are poor among patients with EM and CM (12–17).

Adherence (defined as the extent to which a patient follows their prescribed therapy over a fixed period of time) is an important component of successful oral medication therapy, and the findings from these studies highlight a large gap in care for this highly burdened population. However, there is also a lack of follow-up data about patients who are non-adherent. Persistence may be even more clinically relevant than adherence, as it measures the length of time a patient remains on therapy after treatment initiation. Persistence reflects not only a patient’s adherence but also whether the medicine continues to be prescribed, which may reflect the patient’s experience of efficacy and tolerability. Persistence and time-to-discontinuation of OMPMs, as well as the switching or cycling patterns among patients who discontinue these medications, have not been studied in the CM population.

The aim of the current study is to further elucidate the real-world use of OMPMs in the CM patient population by assessing persistence rates to 14 commonly prescribed OMPMs, determining the average time-to-discontinuation for each medication, and describing switching and treatment re-initiation patterns among those patients who discontinued their initial OMPM.

Methods

Dataset

Data were collected from Truven Health MarketScan® Research Databases (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), which contain inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims for patients covered by US commercial and Medicare Supplemental insurance plans between January 2007 and September 2012, and Medicaid insurance plans (government-funded insurance coverage for individuals unable to afford health care) between January 2007 and December 2011. The inpatient and outpatient claims databases include procedure- and visit-level details from medical claims such as International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, Current Procedural Terminology medical procedure codes, dates of service, and variables describing the financial expenditures of both the patient and their insurance plan. The pharmacy claims database provides prescription dispensing details that include the National Drug Code and generic identifier of the drug dispensed, date dispensed, quantity and days’ supply, and payments made for each claim. A separate eligibility and demographics file provides additional information about each patient, including age, gender, insurance plan type, employment status and classification, geographic location, and enrollment status by month. All patient-level identifiers are encrypted to protect patient privacy, and compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) was ensured by the data administrator, Truven Health Analytics (18). This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division IRB as the dataset was created by a third-party analyst, confirmed to be HIPAA compliant (all data were de-identified), and did not meet the US federal definition of “human subjects research”.

Sample selection

Subjects were selected if they were ≥18 years of age, diagnosed with CM, and initiated an OMPM between 1 January, 2008 and 30 September, 2012. The beginning of the look-back period was chosen as the date when the diagnosis code specific to CM (346.7) was added with the 2008 revision of the ICD-9-CM (19). The analysis included the following commonly prescribed OMPMs: tri-cyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline and nortriptyline; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, citalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine, and paroxetine; serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, venlafaxine; beta-blockers, propranolol, metoprolol, nadolol, and atenolol; and anticonvulsant medications, gabapentin, topiramate, and divalproex. The index date was established by the first pharmacy claim for an OMPM filled among patients with a CM diagnosis.

The following patients were excluded from the analysis: patients taking >1 OMPM on the index date, and patients who did not have continuous insurance plan coverage for six months prior to the index date and 12 months post-index date. In addition, patients whose first pharmacy claim for a beta-blocker was within 12 months after a diagnosis of congestive heart failure (ICD-9-CM 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.10, and 404.XX) or hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401.XX and 405.XX), whose first pharmacy claim for an antidepressant was within 12 months after a diagnosis of depression (ICD-9-CM 290.21, 292.84, 296.XX, 298.0, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, and 311.0), or whose first pharmacy claim for an anticonvulsant was within 90 days of a seizure diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 345.XX) were excluded to avoid including patients who may have been treated with one of the OMPMs in this analysis for a chronic condition other than CM.

Definition and calculation of persistence, switching, and re-initiation

Pharmacy claims data were collected longitudinally for each patient and used to determine discontinuation, which was defined as having a gap between two consecutive claims for the same medication >30 days from the end of the days’ supply of one claim and the start date of the following claim. The date of discontinuation was then established for each patient using the day the patient was expected to run out of their medication based on the days’ supply of the last pharmacy claim.

Persistence rates were calculated using six and 12-month fixed follow-up times after initiating an OMPM. Patients were determined to be persistent if the date of discontinuation was after the pre-specified follow-up period (183 and 365 days for the six and 12-month follow-up times, respectively). Switching was defined to occur when a patient discontinued one OMPM and, within 30 days prior to or 60 days after the discontinuation date of that OMPM, started another OMPM (excluding the previously discontinued OMPM). Treatment re-initiation was defined as any OMPM that was started 60 to 365 days after discontinuation of the previous OMPM (including the previously discontinued OMPM). To be included in the analysis, patients were required to stay enrolled in the health insurance plan for ≥12 months after each switch and/or re-initiation. Those who did not meet the criteria were described as lost to follow-up. Persistence at 12 months was also captured for patients who switched and re-initiated.

Statistical analyses

Baseline patient demographics and comorbidities, the proportion of patients who persisted, as well as switching and re-initiation rates were summarized using descriptive statistics. Comorbid conditions were defined as those with two claims at any time during pre- and post-index periods (i.e., six months before and 12 months after the index date). Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were used to determine the time to discontinuation. Adjusted and unadjusted Cox hazard regression analyses were used to determine the likelihood (i.e., hazard) of non-persistence, using topiramate as a reference drug as it is the most commonly prescribed OMPM and the only OMPM with robust evidence of effectiveness in the CM population (10,11). Due to repeat testing during modeling, the alpha level for statistical significance for the regression models was set at 0.01 (99% confidence interval) using the Bonferroni correction. Discontinuation at 12 adherence months for both switched and re-initiated medications was also reported, and the discontinuation rates were compared among the first, second, and third OMPM initiated.

Results

Patient selection and demographics

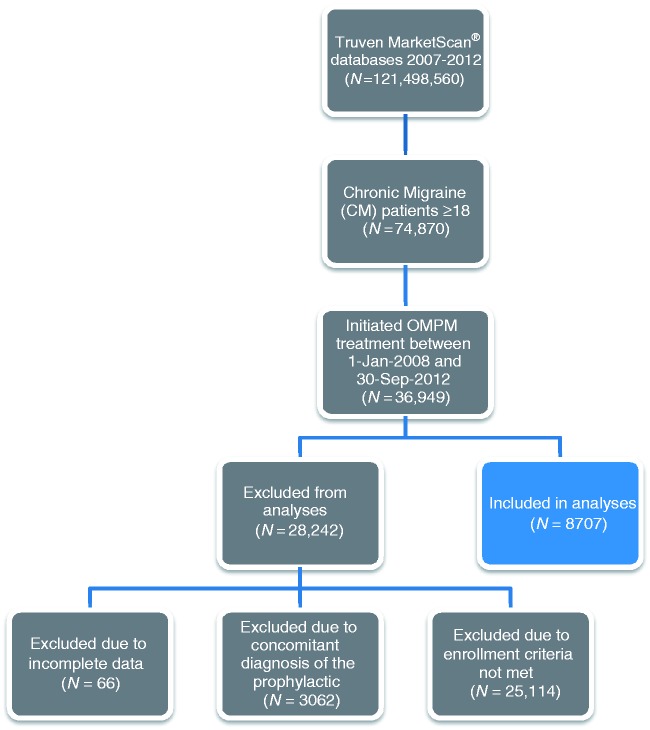

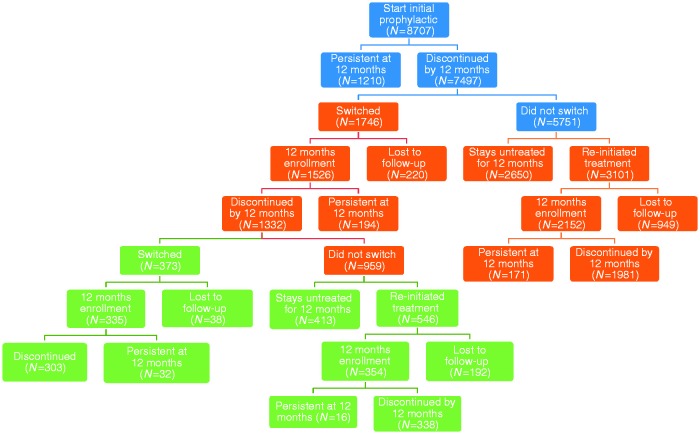

A total of 121 million individuals were identified in the MarketScan Databases between 1 January, 2007 and 30 September, 2012. Of these, 74,870 patients were identified as being ≥18 years of age with a CM diagnosis, of whom 36,949 initiated an OMPM between 1 January, 2008 and 30 September, 2012. A total of 8707 patients (i.e., prevalent cases) ultimately met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in the analyses (Figure 1). Most exclusions (n = 25,114) were because the inclusion criteria were not met (i.e., no continuous enrollment in the insurance plan for the pre-specified study period). Baseline clinical characteristics and demographics stratified by persistence and switching status for these 8707 patients included in the analyses are detailed in Table 1. Appendix 1 provides data on the baseline clinical characteristics and demographics stratified by OMPM. The majority of patients were female, with a mean age of 42 years (standard deviation (SD) = 12 years). A large proportion of patients were working full time (n = 5124, 58.8%) and enrolled in a preferred provider organization health insurance plan (i.e., a commercial health insurance plan in which primary-care physicians are not required to make referrals; n = 5555, 63.8%). Patients from all regions of the United States were represented, with the largest proportion from the South and the smallest from the Northeast. The vast majority of patients resided in or near a metropolitan area during follow-up. The CM patient sample in this analysis had considerable comorbidities, of which the most common were headache disorders other than migraine (n = 4665, 54%), cancer (including patients undergoing investigations to rule out cancer, those in remission, or those undergoing active treatment of confirmed cancer; n = 1895, 22%), hypertension (n = 1531, 18%), depression (n = 1572, 18%), sleep disorder (n = 974, 11%), and gastroesophageal reflux disorder (n = 918, 11%). In general, no striking differences in clinical characteristics or demographics were noted between patients who persisted versus those who discontinued, or those who did or did not switch prophylactics. However, statistically significant differences were observed in employment status, employee classification, and certain comorbidities, although these differences do not appear to be clinically important as the general trends between groups were comparable.

Figure 1.

Patient selection process.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics, stratified by persistence and switching status to the initial OMPM.

| Parameter, n (%) | Persistent (N = 1210) | Discontinued (N = 7497) | p-value | Switched (N = 1746) | Not switched (N = 5751) | p-value | Total (N = 8707) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Years | 42 (12) | 40 (12) | <0.001 | 40 (12) | 38 (12) | <0.001 | 40 (12) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 1028 (85.0) | 6196 (82.6) | 1456 (83.4) | 4740 (82.4) | 7224 (83.0) | ||

| Employment status | 0.062 | 0.030 | |||||

| Full-time | 713 (58.9) | 4411 (58.8) | 1046 (59.9) | 3365 (58.5) | 5124 (58.8) | ||

| Part-time/seasonal | 12 (1.0) | 101 (1.3) | 24 (1.4) | 77 (1.3) | 113 (1.3) | ||

| Retiree | 88 (7.3) | 423 (5.6) | 77 (4.4) | 346 (6.0) | 511 (5.9) | ||

| COBRA/disability/surviving spouse | 5 (0.4) | 55 (0.7) | 16 (0.9) | 39 (0.7) | 60 (0.7) | ||

| Other/unknown | 355 (29.3) | 2194 (29.3) | 495 (28.4) | 1699 (29.5) | 2549 (29.3) | ||

| Missing | 37 (3.1) | 313 (4.2) | 88 (5.0) | 225 (3.9) | 350 (4.0) | ||

| Employee classification | 0.001 | 0.017 | |||||

| Salary | 265 (21.9) | 1439 (19.2) | 348 (19.9) | 1091 (19.0) | 1864 (21.4) | ||

| Hourly | 92 (7.6) | 816 (10.9) | 158 (9.0) | 658 (11.4) | 986 (11.3) | ||

| Non-union | 203 (16.8) | 1340 (17.9) | 313 (17.9) | 1027 (17.9) | 1730 (19.9) | ||

| Union | 63 (5.2) | 312 (4.2) | 83 (4.8) | 229 (4.0) | 473 (5.4) | ||

| Unknown | 550 (45.5) | 3277 (43.7) | 756 (43.3) | 2521 (43.8) | 4143 (47.6) | ||

| Missing | 37 (3.1) | 313 (4.2) | 88 (5.0) | 225 (3.9) | 406 (4.7) | ||

| Geographical location | 0.056 | 0.388 | |||||

| Northeast | 164 (13.6) | 909 (12.1) | 210 (12.0) | 699 (12.2) | 1151 (13.2) | ||

| North Central | 267 (22.1) | 1576 (21.0) | 378 (21.6) | 1198 (20.8) | 2046 (23.5) | ||

| South | 495 (40.9) | 3035 (40.5) | 691 (39.6) | 2344 (40.8) | 3912 (44.9) | ||

| West | 234 (19.3) | 1616 (21.6) | 368 (21.1) | 1248 (21.7) | 2051 (23.6) | ||

| Unknown | 13 (1.1) | 48 (0.6) | 11 (0.6) | 37 (0.6) | 66 (0.8) | ||

| Missing | 37 (3.1) | 313 (4.2) | 88 (5.0) | 225 (3.9) | 406 (4.7) | ||

| Metropolitan statistics | 0.314 | 0.149 | |||||

| Located in an “MSA*”(i.e., urban) | 1005 (83.1) | 6267 (83.6) | 1449 (83.0) | 4818 (83.8) | 7977 (91.6) | ||

| Located outside an “MSA*” (i.e., rural) | 155 (12.8) | 870 (11.6) | 198 (11.3) | 672 (11.7) | 1153 (13.2) | ||

| Missing | 50 (4.1) | 360 (4.8) | 99 (5.7) | 261 (4.5) | 470 (5.4) | ||

| Health plan type† | 0.491 | 0.601 | |||||

| Preferred Provider Organization | 755 (62.4) | 4340 (57.9) | 1032 (59.1) | 3308 (57.5) | 5555 (63.8) | ||

| Health Maintenance Organization | 161 (13.3) | 1360 (18.1) | 304 (17.4) | 1056 (18.4) | 1737 (19.9) | ||

| Non-Capitated Point-of-Service | 111 (9.2) | 709 (9.5) | 149 (8.5) | 560 (9.7) | 946 (10.9) | ||

| Comprehensive | 64 (5.3) | 338 (4.5) | 81 (4.6) | 257 (4.5) | 472 (5.4) | ||

| Other | 91 (7.5) | 562 (7.5) | 136 (7.8) | 426 (7.4) | 696 (8.0) | ||

| Missing | 28 (2.3) | 188 (2.5) | 44 (2.5) | 144 (2.5) | 226 (2.6) | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 107 (8.8) | 652 (8.7) | 0.883 | 158 (9.0) | 494 (8.6) | 0.581 | 759 (8.7) |

| Anxiety | 25 (2.1) | 131 (1.7) | 0.443 | 44 (2.5) | 87 (1.5) | 0.005 | 156 (1.8) |

| Asthma | 94 (7.8) | 623 (8.3) | 0.513 | 173 (9.9) | 450 (7.8) | 0.007 | 717 (8.2) |

| Bipolar disorder | 35 (2.9) | 212 (2.8) | 0.908 | 57 (3.3) | 155 (2.7) | 0.218 | 247 (2.8) |

| Cancer | 278 (23.0) | 1617 (21.6) | 0.286 | 363 (20.8) | 1254 (21.8) | 0.328 | 1895 (21.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 6 (0.5) | 52 (0.7) | 0.430 | 12 (0.7) | 40 (0.7) | 0.961 | 58 (0.7) |

| Coronary heart disease | 42 (3.5) | 208 (2.8) | 0.182 | 39 (2.2) | 169 (2.9) | 0.111 | 250 (2.9) |

| Depression | 219 (18.1) | 1353 (18.0) | 0.989 | 408 (23.4) | 945 (16.4) | <0.001 | 1572 (18.1) |

| Diabetes | 94 (7.8) | 454 (6.1) | 0.024 | 99 (5.7) | 355 (6.2) | 0.419 | 548 (6.3) |

| Epilepsy | 29 (2.4) | 186 (2.5) | 0.853 | 51 (2.9) | 135 (2.3) | 0.185 | 215 (2.5) |

| GERD | 110 (9.1) | 808 (10.8) | 0.073 | 213 (12.2) | 595 (10.3) | 0.033 | 918 (10.5) |

| Hypertension | 236 (19.5) | 1295 (17.3) | 0.063 | 300 (17.2) | 995 (17.3) | 0.856 | 1531 (17.6) |

| Headache (other than migraine) | 601 (49.7) | 4064 (54.2) | 0.003 | 1193 (68.3) | 2871 (49.9) | <0.001 | 4665 (53.6) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 37 (3.1) | 208 (2.8) | 0.588 | 61 (3.5) | 147 (2.6) | 0.039 | 245 (2.8) |

| Neuropathy/neuralgia | 3 (0.2) | 22 (0.3) | 0.781 | 4 (0.2) | 18 (0.3) | 0.565 | 25 (0.3) |

| Renal failure | 10 (0.8) | 57 (0.8) | 0.811 | 8 (0.5) | 49 (0.9) | 0.095 | 67 (0.8) |

| Sleep disorders | 118 (9.8) | 856 (11.4) | 0.084 | 230 (13.2) | 626 (10.9) | 0.010 | 974 (11.2) |

Abbreviations: COBRA: Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, GERD: Gastro esophageal reflux disease, MSA: Metropolitan statistical area, OMPM: Oral migraine preventive medication, SD: Standard deviation.

MSA is defined as the area in and around large metropolitan areas.

Preferred Provider Organization: A health plan in which primary-care physicians are not required to make referrals to specialists; Health Maintenance Organization: A health plan with a designated primary-care physician who must provide referrals to see specialists; Non-Capitated Point-of-Service: A health plan that pays a fixed percentage of costs, regardless of provider; provider reimbursement is based on services rendered; Comprehensive: A health plan that covers a wide range of services.

Persistence and switching patterns

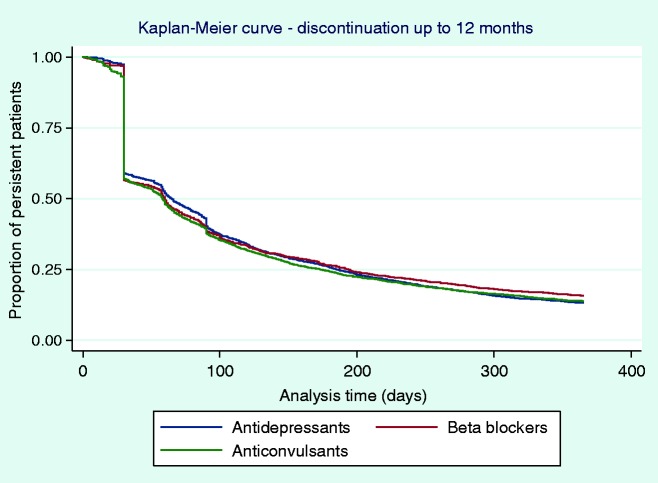

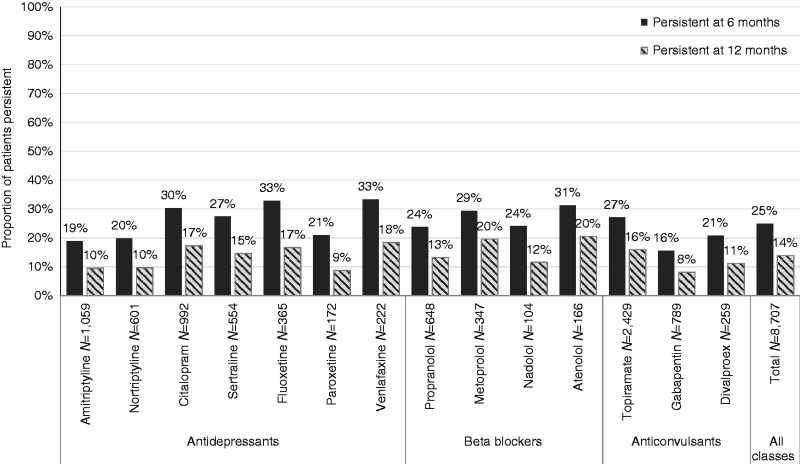

The proportion of patients persisting on their initial OMPM was measured at six and 12 months and stratified by OMPM class (i.e., antidepressants, beta blockers, and anticonvulsants (Figure 2)). Low persistence to the initial OMPM was observed, with approximately three quarters of the patients discontinuing by six months (24 to 26% persistence) regardless of drug class. A sizable decrease in persistence was seen at 12 months, with an additional 10% of patients discontinuing their medication (13 to 16% persistence). The results were further stratified by each individual drug within each class of OMPM, and are provided in Appendix 2. The results were consistent across all individual OMPMs examined.

Figure 2.

Time to discontinuation up to 12 months’ follow-up from the initial prophylactic, stratified by class of OMPM.

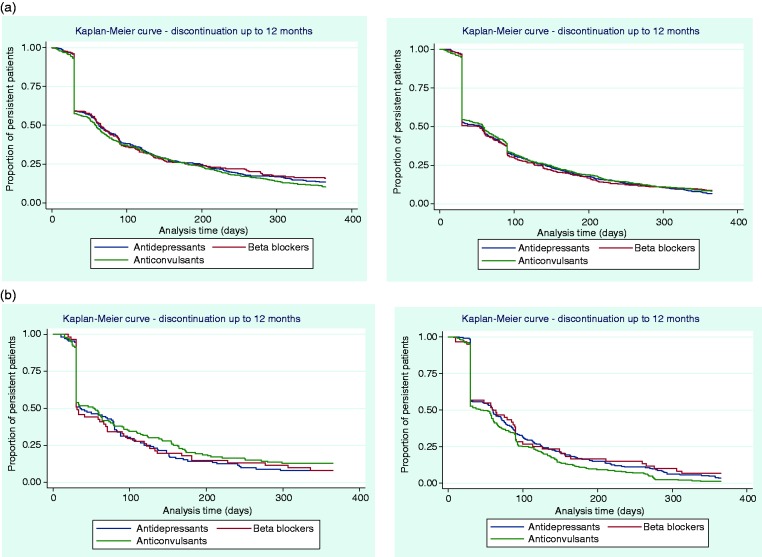

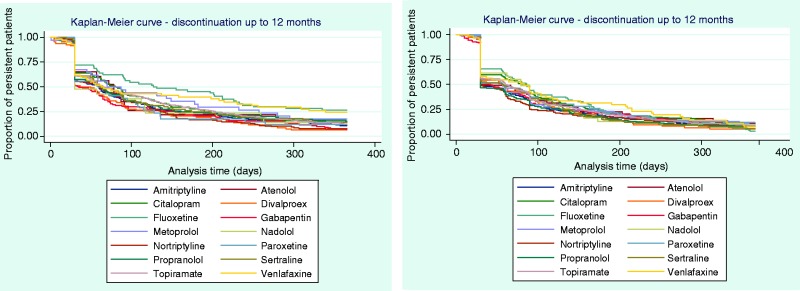

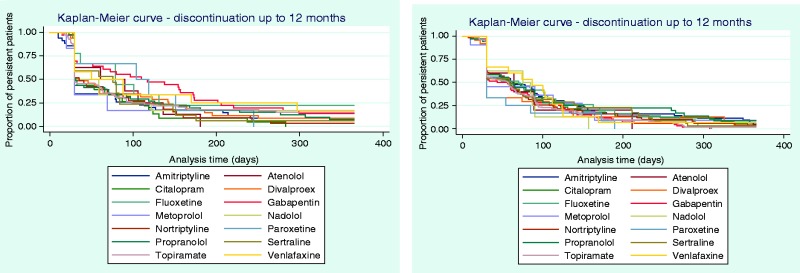

Time to discontinuation from the initial, second, and third OMPM was examined using KM curves (Figures 2 and 3), which showed that many patients discontinued their initial prophylactic OMPM by 30 days, with half of the patients discontinuing by approximately 60 days. Following a switch to a second OMPM, time-to-discontinuation showed similar trends to persistence to the initial OMPM. For patients who re-initiated OMPM therapy, the majority of patients discontinued slightly earlier than patients who switched. Time-to-discontinuation from the third prophylactic shows that nearly half of the patients who switched to a third OMPM discontinued by approximately 30 days, with similar results for patients who re-initiated OMPM therapy. Kaplan-Meier curves for each individual OMPM are provided in Appendices 3–5. Results were similar to the overall drug classes.

Figure 3.

Time to discontinuation up to 12 months’ follow-up from the (a) second prophylactic, first switch (N = 1526, left) or re-initiated (N = 2152, right); (b) third prophylactic, second switch (N = 335, left) or re-initiated (N = 354, right).

Regression analyses were conducted to assess the likelihood of non-persistence to an OMPM at six and 12 months compared with the reference drug, topiramate (Table 2). Results indicated that the likelihood of non-persistence at six months was significantly lower for citalopram (unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 0.88, confidence interval (CI) = 0.78, 0.99). The likelihood of non-persistence was significantly higher at six and 12 months for amitriptyline (six months: HR = 1.24, CI = 1.11, 1.38; 12 months: HR = 1.25, CI = 1.13, 1.38), gabapentin (six months: HR = 1.44, CI = 1.28, 1.62; 12 months: HR = 1.41, CI = 1.27, 1.58), and nortriptyline (six months: HR = 1.18, CI = 1.03, 1.35; 12 months: HR = 1.20, CI = 1.06, 1.36). All other OMPMs did not show statistically different likelihood of non-persistence at either six or 12 months compared with topiramate.

Table 2.

Likelihood of non-persistence at six and 12 months’ follow-up, stratified by OMPM and model used.

| Class of OMPM | Prophylactic | Six month |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model |

Adjusted modela |

|||||||||

| Hazard ratio | 99% CI | p-value | Hazard ratio | 99% CI | p-value | |||||

| Antidepressants | TCAs | Amitriptyline | 1.24 | 1.11 | 1.38 | <0.001 b | 1.22 | 1.10 | 1.36 | <0.001 b |

| Nortriptyline | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.35 | 0.001 b | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.34 | 0.002 b | ||

| SSRIs | Citalopram | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.004 b | 0.89 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.008 b | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.85 | 0.71 | 1.01 | 0.014 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 1.03 | 0.029 | ||

| Paroxetine | 1.11 | 0.89 | 1.40 | 0.222 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 1.40 | 0.224 | ||

| Sertraline | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.09 | 0.329 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.09 | 0.317 | ||

| SNRI | Venlafaxine | 0.85 | 0.68 | 1.06 | 0.057 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 1.10 | 0.139 | |

| Antihypertensives | Beta blockers | Atenolol | 0.89 | 0.69 | 1.14 | 0.222 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 1.19 | 0.414 |

| Metoprolol | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.12 | 0.365 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.18 | 0.859 | ||

| Nadolol | 1.10 | 0.81 | 1.47 | 0.426 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 1.49 | 0.360 | ||

| Propranolol | 1.10 | 0.97 | 1.26 | 0.051 | 1.10 | 0.96 | 1.25 | 0.071 | ||

| Anti-epileptics | Anticonvulsantsc | Divalproex | 1.18 | 0.97 | 1.43 | 0.026 | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.44 | 0.020 |

| Gabapentin | 1.44 |

1.28 |

1.62 |

<0.001

b

|

1.49 |

1.32 |

1.68 |

<0.001

b

|

||

| 12 month |

||||||||||

| Antidepressants | TCAs | Amitriptyline | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.38 | <0.001 b | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.36 | <0.001 b |

| Nortriptyline | 1.20 | 1.06 | 1.36 | <0.001 b | 1.20 | 1.06 | 1.36 | <0.001 b | ||

| SSRIs | Citalopram | 0.90 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.012 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 0.018 | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.91 | 0.77 | 1.06 | 0.113 | 0.92 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.210 | ||

| Paroxetine | 1.16 | 0.94 | 1.43 | 0.077 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 1.43 | 0.087 | ||

| Sertraline | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.12 | 0.676 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.11 | 0.609 | ||

| SNRI | Venlafaxine | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.08 | 0.107 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 0.228 | |

| Antihypertensives | Beta blockers | Atenolol | 0.87 | 0.69 | 1.10 | 0.119 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 0.284 |

| Metoprolol | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.164 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 0.584 | ||

| Nadolol | 1.14 | 0.87 | 1.50 | 0.220 | 1.15 | 0.88 | 1.52 | 0.182 | ||

| Propranolol | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 0.031 | 1.10 | 0.97 | 1.25 | 0.042 | ||

| Anti-epileptics | Anticonvulsantsc | Divalproex | 1.18 | 0.98 | 1.41 | 0.020 | 1.19 | 0.99 | 1.42 | 0.014 |

| Gabapentin | 1.41 | 1.27 | 1.58 | <0.001 b | 1.47 | 1.31 | 1.65 | <0.001 b | ||

Abbreviations: OMPM: Oral migraine preventive medication; SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA: Tricyclic antidepressant.

Adjusted for demographics: Age, sex, employee status, employee classification, region, metropolitan area versus rural, plan type, total prescription cost, and comorbidities: Anxiety, bipolar disorder, cancer, congenital heart defect, diabetes, depression, epilepsy, hypertension, headache, sleep disorder.

Statistically significant, 99% confidence interval (p < 0.01).

Topiramate was used as the reference OMPM; therefore, it is not included in this table.

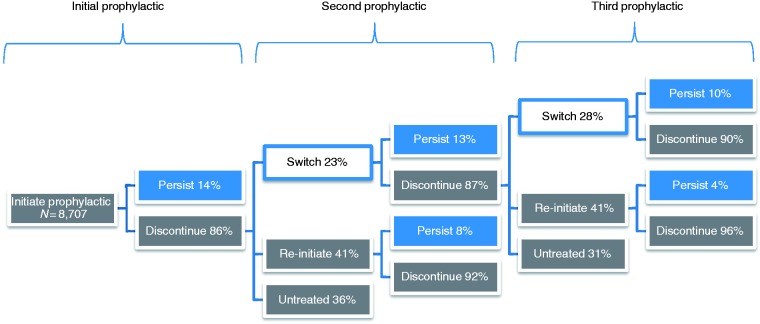

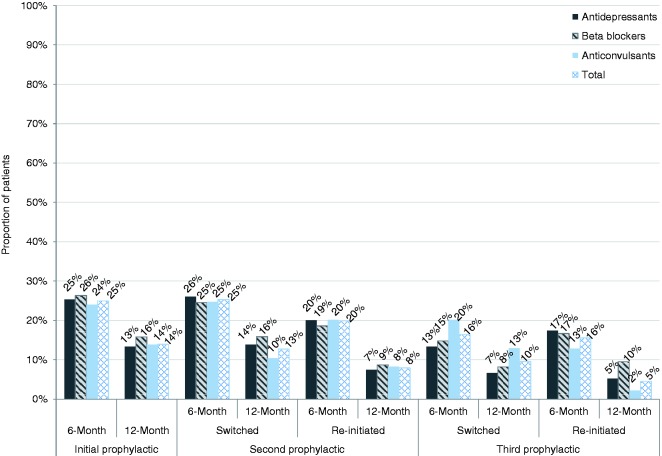

Following their first or second prophylactic, nearly a quarter of the patients switched to another OMPM (Figure 4), with 10 to 13% remaining persistent on their new OMPM at the 12-month follow-up. The majority of patients (>86%) discontinued their first, second, or third prophylactic OMPM. Of those patients who discontinued their first or second OMPM, 41% re-initiated OMPM therapy within one year. Persistence rates among re-initiated patients were lower than those patients who switched OMPMs, with 4 to 8% of re-initiated patients persisting on their OMPM at 12 months. Approximately one third of the patients who discontinued treatment remained untreated for the 12-month follow-up period after discontinuation. Overall, the trends in persistence data were consistent regardless of OMPM class, with persistence decreasing over the various cycles (Figure 5). Between 24 to 26% and 13 to 16% of patients remained persistent on their initial OMPM at six and 12 months, respectively. The proportion of persistent patients declined considerably by their third OMPM (13 to 20% and 2 to 13% at six and 12 months, respectively), regardless of the type of OMPM and whether they had switched or re-initiated. Data on switching and re-initiation patterns, as well as patient disposition at each treatment cycle, are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients who were persistent, switched, or re-initiated a prophylactic OMPM for the treatment of chronic migraine.

Figure 5.

Persistence at six and 12 months’ follow-up on the first three cycles of OMPMs.

Figure 6.

Switching and re-initiation patterns and patient disposition.

Discussion

This study is the first to describe OMPM persistence, time-to-discontinuation, and switching behaviors in an identified CM population. Our results indicate that persistence to OMPMs is low and decreases further as patients cycle through multiple prophylactics. The average time-to-discontinuation was about two to three months, which is in line with recommended guidelines for an adequate trial of these therapies. However, KM curves (Figures 2 and 3) showed that there was a sharp drop-off in persistence at 30 days, which may indicate that a lot of patients were not continuing treatment past their first prescription refill. Furthermore, over two thirds of patients discontinued their medication by six months and more than four fifths by 12 months. This is concerning, as guidelines recommend that patients stay on OMPM therapy for at least 6–12 months before being evaluated for discontinuation (9). After discontinuing their initial prophylactic, only one fourth (25%) of patients switched to another medication within 60 days of discontinuation. Most patients (41%) re-initiated therapy at a later time or remained untreated for an extended period (31 to 36%). Among the patients who switched or re-initiated, we found that persistence worsened as patients cycled through their first three prophylactics.

To our knowledge, one other study has investigated persistence with OMPMs (13). This study investigated persistence to four commonly prescribed OMPMs (amitriptyline, divalproex, topiramate, and propranolol) in the general migraine population using a claims database analysis from five regional managed care organizations throughout the US. The authors found that persistence to OMPMs in the general migraine population was approximately 18.5% at six months and 11.5% at 12 months. This was similar to the rates we found (25% and 14%, respectively). The slightly higher persistence rates in our study may be attributed to the fact that our population was comprised of patients with CM rather than general migraine, and hence was a more severely affected population. Greater headache severity and frequency may be associated with a greater incentive to remain adherent on their medication due to their disease severity. The KM curves were similar between our two studies, especially in regard to the sharp decline in patients who remained persistent past the first prescription refill (30-day mark). A greater differential between persistence rates in the CM population and the general migraine population may have been expected; however, without a direct comparison with general migraine or EM, we can only speculate about whether adherence and persistence rates would vary for these populations.

Yaldo et al (13) also concluded that topiramate was associated with better persistence that was statistically significant in adjusted Cox hazard regression models versus amitriptyline, divalproex, and propranolol. Our results were slightly different in this regard. Of these three OMPMs, our Cox regression models suggested that only amitriptyline was associated with a lower likelihood of persistence than topiramate, but that divalproex and propranolol were not.

Since CM is a chronic disease, it is reasonable to also compare our results with studies of patients with other chronic conditions requiring similar daily oral medication therapy. Yeaw et al. used a national database of medical claims to compare persistence among six chronic diseases over a 12-month follow-up period (20). Persistence in Yeaw’s study ranged from 18% persistence for overactive bladder medications, to 54% for oral diabetes medications, suggesting that persistence across all six chronic conditions reported in their study was higher than in our study, where persistence at 12 months was 14% in patients with CM. One likely explanation for these differences in persistence rates may be that Yeaw et al. considered patients who were cycling between medications of the same class as being persistent. In our study, persistence was calculated for each individual OMPM, with the results then grouped by class. The rationale for our approach was that OMPMs must often be titrated downward before another medication is initiated, and the new medication may take up to three months to take effect (9). This is very different from oral antidiabetic agents where, for example, sulfonylureas can be easily interchanged without an adjustment period. The difference in persistence among medications used for these chronic diseases compared with our results among patients with CM is still very compelling when we take into account that patients with CM experience ≥15 headache days on a monthly basis. Given the symptomatic nature of migraine and its interference with daily activities, one may expect the latter to motivate patients to have higher adherence (contributing toward higher persistence) compared to other chronic conditions, wherein patients do not necessarily exhibit daily signs and/or symptoms.

There are several important limitations that must be considered when interpreting our results. First, we assumed that a claim represented ingestion of the medication; we have no way to confirm this. We also assumed that the ICD-9-CM codes accurately reflect the migraine diagnosis and comorbid conditions. It is possible that there are inaccuracies or inconsistences in the coding of CM and other conditions due to the number and range of healthcare providers contributing to the database, but again we have no way to confirm this. With regard to the metropolitan statistical area (MSA, an indicator of urban versus rural domicile) and employment variables, there is some uncertainty to be acknowledged as some MSA areas may actually include both rural and metropolitan areas. As for employer data, this variable describes only the person who is the primary enrollee, therefore the other beneficiaries who may comprise a subset of the overall sample may not be represented correctly in the dataset. Claims data also lack important clinical information, such as disease severity, which would aid in interpreting our results. Chronic migraine encompasses patients who experience ≥15 headache days per month; however, a patient who experiences 15 headache days per month may be very different from a patient who experiences 30 headache days per month. Patients along this continuum of migraine frequency may vary widely in their attitudes and behaviors related to their migraine preventive medication treatment. Finally, the severity of each headache may also vary among patients; this is not captured in claims data and thus we are not able to use such data to inform our analyses.

One of the most important pieces of information we lack is the exact reason for discontinuation of a given OMPM. This information is neither directly available nor can be inferred from claims data. Understanding the reason(s) why patients discontinue and/or switch OMPMs would help in understanding the treatment patterns we observed. One logical explanation may be that these medications are not efficacious and/or produce side effects, and patients do not feel the benefit-risk tradeoff is worthwhile. This was the finding of one large cross-sectional observational study by Blumenfeld et al. that used data from the International Burden of Migraine Survey II in 2013, where results revealed that lack of efficacy and side effects were the two largest drivers of discontinuation of OMPMs (21). The lack of clear guidelines to inform the selection of preventive therapy in patients with CM may contribute to discontinuation, if the presumed lack of efficacy is attributed to suboptimal dosages in this population. In addition, as topiramate is the only OMPM assessed in the CM population (10,11), it is possible that the other OMPMs, while effective for patients with EM, are not effective for patients with CM.

A recently published systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the top three most commonly used OMPMs revealed pooled results of discontinuation and the reasons for discontinuation (16). The most commonly cited reasons for discontinuation were adverse events, patient choice, and loss to follow-up. The results from both of these studies are consistent with our conjecture that discontinuations were due to side effects or lack of efficacy. Although the reasons for discontinuation for the patients in our current analyses cannot be known, these studies provide some insight into possible explanations.

Further investigation comparing the level of persistence in subpopulations of patients with migraine (e.g., patients with CM vs EM, patients with comorbid conditions for which OMPMs are frequently prescribed versus patients without these conditions) would be useful to help understand the impact of disease severity on OMPM persistence. In addition, clinical research into the reasons for discontinuation of OMPMs, stratified by level of evidence of efficacy, in patients with CM would further support optimal disease management.

Conclusion

Persistence to OMPMs is low among the US CM population at six months, and declines further by 12 months. Switching or re-initiating treatment after discontinuation is common, but results indicate that discontinuation rates worsen as patients cycle through additional OMPMs. Further research evaluating reasons for discontinuation and strategies to improve persistence are needed.

Clinical implications

Persistence to commonly prescribed oral migraine-preventive medications is poor, with higher discontinuation rates in patients who cycle through various medications

Although the results from this study highlight the gap in therapy for patients with chronic migraine, further research is needed to evaluate the reasons for non-persistence and strategies to improve persistence

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Amy Kuang, Allergan plc, for editorial support on this manuscript.

Appendix 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics by OMPM.

| Parameter, n (%) | Amitriptyline (N = 1059) | Nortriptyline (N = 601) | Citalopram (N = 992) | Sertraline (N = 554) | Fluoxetine (N = 365) | Paroxetine (N = 172) | Venlafaxine (N = 222) | Propranolol (N = 648) | Metoprolol (N = 347) | Atenolol (N = 166) | Nadolol (N = 104) | Topiramate (N = 2429) | Gabapentin (N = 789) | Divalproex (N = 259) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39 (12) | 40 (12) | 39 (12) | 38 (12) | 40 (11) | 39 (11) | 42 (12) | 38 (12) | 46 (13) | 44 (13) | 39 (12) | 39 (12) | 45 (12) | 42 (12) | <0.001 |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 865 (82) | 466 (78) | 850 (86) | 480 (87) | 325 (89) | 141 (82) | 201 (91) | 520 (80) | 263 (76) | 138 (83) | 83 (80) | 2083 (86) | 632 (80) | 177 (68) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Full-time | 621 (59) | 374 (62) | 589 (59) | 334 (60) | 224 (61) | 99 (58) | 122 (55) | 391 (60) | 170 (49) | 102 (61) | 67 (64) | 1478 (61) | 411 (52) | 142 (55) | |

| Part-time/seasonal | 13 (1) | 12 (2) | 16 (2) | 8 (1) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 32 (1) | 8 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Retiree | 58 (5) | 41 (7) | 46 (5) | 28 (5) | 13 (4) | 10 (6) | 14 (6) | 25 (4) | 40 (12) | 11 (7) | 5 (5) | 122 (5) | 82 (10) | 16 (6) | |

| COBRA/disability/ surviving spouse | 4 (0) | 3 (0) | 7 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 1 (0) | 7 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (1) | 6 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Other/unknown | 302 (29) | 156 (26) | 281 (28) | 156 (28) | 102 (28) | 53 (31) | 65 (29) | 205 (32) | 114 (33) | 45 (27) | 28 (27) | 728 (30) | 243 (31) | 71 (27) | |

| Missing | 61 (6) | 15 (2) | 53 (5) | 24 (4) | 19 (5) | 9 (5) | 12 (5) | 21 (3) | 14 (4) | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | 53 (2) | 39 (5) | 22 (8) | |

| Employee Classification | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Salary | 621 (59) | 374 (62) | 589 (59) | 334 (60) | 224 (61) | 99 (58) | 122 (55) | 391 (60) | 170 (49) | 102 (61) | 67 (64) | 1478 (61) | 411 (52) | 142 (55) | |

| Hourly | 13 (1) | 12 (2) | 16 (2) | 8 (1) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 32 (1) | 8 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Non-union | 58 (5) | 41 (7) | 46 (5) | 28 (5) | 13 (4) | 10 (6) | 14 (6) | 25 (4) | 40 (12) | 11 (7) | 5 (5) | 122 (5) | 82 (10) | 16 (6) | |

| Union | 4 (0) | 3 (0) | 7 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 1 (0) | 7 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (1) | 6 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| Unknown | 302 (29) | 156 (26) | 281 (28) | 156 (28) | 102 (28) | 53 (31) | 65 (29) | 205 (32) | 114 (33) | 45 (27) | 28 (27) | 728 (30) | 243 (31) | 71 (27) | |

| Missing | 61 (6) | 15 (2) | 53 (5) | 24 (4) | 19 (5) | 9 (5) | 12 (5) | 21 (3) | 14 (4) | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | 53 (2) | 39 (5) | 22 (8) | |

| Geographical location | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 143 (14) | 103 (17) | 101 (10) | 64 (12) | 37 (10) | 17 (10) | 25 (11) | 82 (13) | 38 (11) | 29 (17) | 13 (13) | 310 (13) | 80 (10) | 31 (12) | |

| North Central | 226 (21) | 121 (20) | 204 (21) | 127 (23) | 79 (22) | 40 (23) | 49 (22) | 149 (23) | 77 (22) | 32 (19) | 30 (29) | 485 (20) | 158 (20) | 66 (25) | |

| South | 377 (36) | 191 (32) | 436 (44) | 225 (41) | 151 (41) | 65 (38) | 93 (42) | 243 (38) | 149 (43) | 66 (40) | 51 (49) | 1080 (44) | 308 (39) | 95 (37) | |

| West | 241 (23) | 168 (28) | 193 (19) | 110 (20) | 77 (21) | 41 (24) | 43 (19) | 146 (23) | 67 (19) | 33 (20) | 7 (7) | 485 (20) | 196 (25) | 43 (17) | |

| Unknown | 11 (1) | 3 (0) | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (1) | 8 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Missing | 61 (6) | 15 (2) | 53 (5) | 24 (4) | 19 (5) | 9 (5) | 12 (5) | 21 (3) | 14 (4) | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | 53 (2) | 39 (5) | 22 (8) | |

| Metropolitan Statistics | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Located in an MSA | 861 (81) | 538 (90) | 818 (82) | 455 (82) | 300 (82) | 141 (82) | 185 (83) | 545 (84) | 290 (84) | 153 (92) | 80 (77) | 2065 (85) | 648 (82) | 193 (75) | |

| Located outside an MSA | 126 (12) | 45 (7) | 116 (12) | 71 (13) | 44 (12) | 22 (13) | 25 (11) | 75 (12) | 41 (12) | 7 (4) | 21 (20) | 296 (12) | 94 (12) | 42 (16) | |

| Missing | 72 (7) | 18 (3) | 58 (6) | 28 (5) | 21 (6) | 9 (5) | 12 (5) | 28 (4) | 16 (5) | 6 (4) | 3 (3) | 68 (3) | 47 (6) | 24 (9) | |

| Health plan type | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Preferred Provider Organization | 608 (57) | 333 (55) | 574 (58) | 321 (58) | 212 (58) | 98 (57) | 129 (58) | 400 (62) | 213 (61) | 91 (55) | 55 (53) | 1458 (60) | 464 (59) | 139 (54) | |

| Health Maintenance Organization | 192 (18) | 122 (20) | 187 (19) | 100 (18) | 73 (20) | 34 (20) | 36 (16) | 114 (18) | 51 (15) | 32 (19) | 14 (13) | 395 (16) | 132 (17) | 39 (15) | |

| Non-Capitated Point-of-Service | 100 (9) | 59 (10) | 95 (10) | 48 (9) | 29 (8) | 20 (12) | 16 (7) | 49 (8) | 29 (8) | 22 (13) | 17 (16) | 235 (10) | 69 (9) | 32 (12) | |

| Comprehensive | 52 (5) | 24 (4) | 53 (5) | 22 (4) | 19 (5) | 5 (3) | 12 (5) | 29 (4) | 30 (9) | 10 (6) | 6 (6) | 71 (3) | 49 (6) | 20 (8) | |

| Other | 85 (8) | 51 (8) | 64 (6) | 42 (8) | 23 (6) | 10 (6) | 22 (10) | 43 (7) | 11 (3) | 8 (5) | 11 (11) | 206 (8) | 56 (7) | 21 (8) | |

| Missing | 22 (2) | 12 (2) | 19 (2) | 21 (4) | 9 (2) | 5 (3) | 7 (3) | 13 (2) | 13 (4) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 64 (3) | 19 (2) | 8 (3) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 92 (9) | 51 (8) | 98 (10) | 41 (7) | 30 (8) | 25 (15) | 25 (11) | 50 (8) | 27 (8) | 13 (8) | 14 (13) | 208 (9) | 57 (7) | 28 (11) | 0.096 |

| Anxiety | 21 (2) | 8 (1) | 24 (2) | 16 (3) | 14 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 12 (2) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 28 (1) | 10 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.021 |

| Asthma | 100 (9) | 39 (6) | 86 (9) | 51 (9) | 30 (8) | 15 (9) | 21 (9) | 21 (3) | 28 (8) | 9 (5) | 7 (7) | 205 (8) | 75 (10) | 30 (12) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 15 (1) | 4 (1) | 45 (5) | 12 (2) | 17 (5) | 11 (6) | 12 (5) | 13 (2) | 9 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (5) | 57 (2) | 26 (3) | 18 (7) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 225 (21) | 123 (20) | 206 (21) | 127 (23) | 74 (20) | 25 (15) | 55 (25) | 136 (21) | 95 (27) | 44 (27) | 18 (17) | 498 (21) | 211 (27) | 58 (22) | 0.002 |

| Congestive heart failure | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 10 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 9 (0) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.004 |

| Coronary heart disease | 18 (2) | 8 (1) | 28 (3) | 13 (2) | 9 (2) | 2 (1) | 10 (5) | 8 (1) | 57 (16) | 10 (6) | 4 (4) | 46 (2) | 27 (3) | 10 (4) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 176 (17) | 81 (13) | 324 (33) | 179 (32) | 115 (32) | 52 (30) | 76 (34) | 61 (9) | 43 (12) | 17 (10) | 10 (10) | 256 (11) | 138 (17) | 44 (17) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 58 (5) | 29 (5) | 75 (8) | 31 (6) | 18 (5) | 11 (6) | 15 (7) | 30 (5) | 40 (12) | 20 (12) | 5 (5) | 119 (5) | 83 (11) | 14 (5) | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy | 15 (1) | 9 (1) | 28 (3) | 15 (3) | 8 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | 9 (1) | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 67 (3) | 23 (3) | 19 (7) | <0.001 |

| GERD | 121 (11) | 57 (9) | 122 (12) | 54 (10) | 40 (11) | 20 (12) | 23 (10) | 59 (9) | 53 (15) | 20 (12) | 10 (10) | 192 (8) | 113 (14) | 34 (13) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 149 (14) | 83 (14) | 163 (16) | 93 (17) | 70 (19) | 29 (17) | 41 (18) | 100 (15) | 183 (53) | 63 (38) | 17 (16) | 313 (13) | 179 (23) | 48 (19) | <0.001 |

| Headache (other than migraine) | 627 (59) | 365 (61) | 479 (48) | 251 (45) | 168 (46) | 84 (49) | 99 (45) | 369 (57) | 155 (45) | 82 (49) | 56 (54) | 1344 (55) | 423 (54) | 163 (63) | <0.001 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 38 (4) | 11 (2) | 36 (4) | 20 (4) | 12 (3) | 4 (2) | 7 (3) | 16 (2) | 12 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (5) | 55 (2) | 16 (2) | 10 (4) | 0.189 |

| Neuropathy/neuralgia | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 9 (1) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 4 (0) | 7 (1) | 9 (1) | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 8 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (1) | 7 (1) | 4 (2) | 0.070 |

| Sleep disorders | 140 (13) | 75 (12) | 141 (14) | 65 (12) | 42 (12) | 20 (12) | 39 (18) | 50 (8) | 45 (13) | 13 (8) | 15 (14) | 226 (9) | 72 (9) | 31 (12) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: COBRA: Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, GERD: Gastro esophageal reflux disease, MSA: Metropolitan statistical area, SD: Standard deviation. Note: bolded p values are significant.

Appendix 2. Persistence on the initial OMPM at six and 12 months’ follow-up stratified by individual OMPM.

Appendix 3. Time to discontinuation at 12 months’ follow-up from the initial prophylactic, stratified by individual OMPM.

Appendix 4. Time to discontinuation at 12 months’ follow-up from the second prophylactic, first switch (N = 1526, left) or re-initiated (N = 2152, right), stratified by individual OMPM.

Appendix 5. Time to discontinuation at 12 months’ follow-up from the third prophylactic, second switch (N = 335, left) or re-initiated (N = 546, right), stratified by individual OMPM.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Zsolt Hepp was an employee of Allergan plc at the time of this analysis and during the manuscript draft process. Dr David Dodick has received consulting honoraria from Allergan, Amgen, Alder, Arteaus, Pfizer, Colucid, Merck, ENeura, NuPathe, Eli Lilly & Company, Autonomic Technologies, Ethicon, J&J, Zogenix, Supernus, Labrys, receives honoraria from Sage Publishing as editor of Cephalagia, has received honoraria/royalties for publishing with WebMD, UptoDate, Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, and has received honoraria for speaking engagements/lectures at IntraMed, Synergy, Universal Meeting Management, Sun Pharma, Starr Clinical, Decision Resources, American Academy of Neurology, American Headache Society, Laval University, Western Virginia University Foundation, Texas Neurological Society, Canadian Headache Society. Drs Sepideh Varon and Patrick Gillard are employees and stockholders of Allergan plc. Dr Jenny Chia and Nitya Matthew were employees of Allergan plc during the preparation of this manuscript. Drs Ryan Hansen and Emily Beth Devine have nothing to declare.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Allergan plc.

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 629–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache 2012; 52: 1456–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazard E, Munakata J, Bigal ME, et al. The burden of migraine in the United States: Current and emerging perspectives on disease management and economic analysis. Value Health 2009; 12: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007; 68: 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanteri-Minet M, Duru G, Mudge M, et al. Quality of life impairment, disability and economic burden associated with chronic daily headache, focusing on chronic migraine with or without medication overuse: A systematic review. Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 837–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. Migraine: Epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progression. Headache 2005; 45: S3–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: Pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 2012; 78: 1337–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate for the treatment of chronic migraine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache 2007; 47: 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diener HC, Bussone G, Van Oene JC, et al. Topiramate reduces headache days in chronic migraine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2007; 27: 814–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulleners WM, Whitmarsh TE, Steiner TJ. Noncompliance may render migraine prophylaxis useless, but once-daily regimens are better. Cephalalgia 1998; 18: 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaldo AZ, Wertz DA, Rupnow MF, et al. Persistence with migraine prophylactic treatment and acute migraine medication utilization in the managed care setting. Clin Ther 2008; 30: 2452–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafata JE, Tunceli O, Cerghet M, et al. The use of migraine preventive medications among patients with and without migraine headaches. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, et al. Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract 2012; 12: 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm 2014; 20: 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2015; 35: 478–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Truven Health Analytics. MarketScan Database: Better understand health economics and treatment outcomes, http://truvenhealth.com/markets/life-sciences/products/data-tools/marketscan-databases (accessed 1 November 2016).

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Baltimore, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

- 20.Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, et al. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm 2009; 15: 728–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: Results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache 2013; 53: 644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]